Before the Corps

The Great Depression of the 1930s caused hundreds of thousands of families to lose their homes and become nomads. Every day became a challenge to live. Looking for refuge, folks would often stop for the night or camp out for weeks in the flimsiest of shelters, often thankful to stay in some ramshackle shanty or falling-down shed, desperate to find enough food to feed the children. Because the burden of their plight disheartened many such drifting families, teenagers, by nature energetic, wanting to work, and to varying degrees ambitious, often decided to go off on their own, either to assist their family in some way, or to at least alleviate the burden on their parents. Then of course, there was the call of adventure, and because it had become so commonplace, the quixotic image of a carefree life on the road—which, of course, quickly faded after several nights under the stars, or after a number of missed meals. Also, as many youths found out, the makeshift camps that tramps and drifters stopped in overnight often included ruthless, callous individuals that had no qualms about cheating someone, especially unsuspecting youths. Most hobo jungles were aptly named. Teenagers found that the best way to strike out on their own was to get involved in some venture that offered them shelter, allowed them to travel, and at the same time, gave them a sense of purpose, all while the country struggled economically to get back on its feet.

As I started my teenage years, I guess that my outdoor style of upbringing had sort of instilled in me a strong sense of restlessness. I finally dropped out of Kenmore High School in June of 1938 at 15 years of age. Times were tough, and another depression had started, sort of like an extension of the big one that had hit us in 1929. So I decided to join the Civilian Conservation Corps, the CCC.1

One good reason was because we were poor and I needed some sort of work to support myself and help support my family. Another was just the fact that I could get out on my own and get to go out West for adventures, and also get paid for helping improve the land.

I think my going off was sort of inevitable. I had this wanderlust; I would have eventually gone off on my own anyway, going somewhere, anywhere, because I grew up as a rover. Joining the CCC was the chance I wanted to get away from home; I felt it was time.

A big reason though was to get away from my father.

There had been some trouble brewing with him for a while. Part of the reason was that I was now a teenager and my hormones were in play. Also I was growing to be a stubborn little cuss, and, as such, my resentment towards the way he treated all of us was increasing. Often, he would work on a job, get paid, and then go to a bar, and start drinking his money away. Alex and I would finally have to go looking for him, sometimes finding him in an alley passed out. We then somehow had to get him home. What made it much worse was that hardly anyone could reason with him when he had been drinking, and he was doing more and more of that. Alex took his guff well enough because he was more obedient. But I became more and more upset with his cranky moods, and especially the way he treated mom.

That is not to say that he did not have his good points. When he was sober, he usually was okay, although even then he had occasional moods. Sometimes, he would go a month or even two without taking a drink and was usually easy to get along with. Then he would fall off the wagon and go into one or more of his mean drunks. Afterwards, he would be sorry for what he had done, or just deny ever having been that way, sometimes even laughing about it with “Aw, c’mon. I wasn’t like that,” or “I didn’t do that.” I found out in later years that there was actually a term for that: a “periodic alcoholic.”2

Things between the two of us came to a head in the late spring of 1938. We were living at 2941 Wingate Avenue at the time. We had built the house on a slant, so the front end was low to the ground. One day, we were working on the house, my father and I both standing on a scaffold. He noticed something that really upset him and somehow figured that it was my fault. So he started in on me. Yelling at what I had done, he gave me hell. Upset, and on the spur of the moment, I badmouthed him back. He got furious and tried to take a swing at me. I ducked, jumped off the scaffold and took off. Not knowing where to go, I finally went over to Waddy’s house to stay there until the old man calmed down.

I avoided him for three days, staying with my friend. Finally, at my mom’s insistence, I reluctantly came home. It was evening as I walked into the house, my radar up, ready for anything. The old man saw me come in and just glared at me. Mom, perhaps trying to divert trouble, told us that supper was ready. Everyone sat down, with me, still hesitant, coming into the dining room last. Pop as usual sat at the head of the table, and slowly, hesitantly, I sat down in my spot, which unfortunately was the chair just to his left.

Pop sat there giving me a dirty look. I tried to look penitent and did not say anything. That did not help though. All this time, he had been festering over my disrespectful behavior and then taking off and not being around to be punished. In a sudden fit of rage, he swung at me with his left fist. He landed a solid shot on my chin, knocking me backward off my chair and onto the floor. My head woozy, I slowly got up and gritted my teeth. I left the table and went to my room, swearing to myself that I would never ever let him hit me again.

Perhaps if that had been the end of it, I might have worked through his temperament. Unfortunately though, I soon realized that he was not satisfied. So for the next few days, I tried to avoid him. A week after that incident at the table came another. That day, everyone was gone. I was totally alone in the house. I fixed me a late afternoon snack and had just sat down at the dinner table when the front door opened and my father came in. I could tell that he’d been drinking and was in a foul mood.

I tried to stay calm. He walked into the kitchen and came out holding a large carving knife in one hand. He picked up a china plate and sat down at his usual spot next to me. Sitting there drunk, looking angrily at me, he took the knife and tapped it on the plate. Then he did it again, letting the knife edge hit the plate. He whacked the plate again, stronger this time, doing a slow burn, staring at me. Another whack and I noticed small slivers of china were breaking off the plate’s surface. Another smack, and more slivers. Pop kept sitting there, glaring at me, slowly hacking this plate to pieces. Then he started muttering that I was a no-good rotten this and that, and once in a while slipping in a veiled threat.

Finally, finished eating and not knowing what else to do, I stood up. Pop began to stagger to his feet. Before he could fully stand up, I grabbed for his hands. Somehow, I got the knife away from him and tossed it to the floor. But because somewhere deep within me I still respected him, I decided that I would not hit him if I could help it.

Growling, he lurched at me, but in his sloshed condition, he was slow and unsteady. I grabbed him from behind. Pop struggled, but I had too firm a grip on him. Grimly I held on as he kept trying to break free. Pop was not in shape though, and being overweight, much older, and, of course, drunk, he could not get out of my bear hug. I could tell that he already was getting tired. Finally, in frustration, he stiffened his body and lurched backward. We both went flying back and fell into the side of the davenport, knocking it over. I held on though, and as we rolled onto the floor, I kept my bear hug around him. He could not get loose. Finally, drunk as all get out, as we lay there, he started crying, looking for sympathy, feeling sorry for himself.

We finally made our peace, but I realized at that point that I had to move out. Going over my options the next few days, I concluded that the CCC seemed the best way to do that. After all, Alex had joined a year ago, and had done well, working on projects in Ohio. He had worked on that big park in Akron, and then gone down to old Shonbrook village, staying in a cabin.

My joining would remove my constant annoying presence, make some money for the family, and let me go on an adventure somewhere, all expenses paid, and being away from the Akron area would do both me and Pop a lot of good. Everyone could save face. And I also hoped that he might treat my mother better if I got off the scene.

The only problem was that I was still 15 years old and technically too young to join by two years and three months. So I sort of “modified” my birth certificate to reflect an older age. I thought adding two more years would be believable, and close enough to allow me to join, because in a few months, I would turn “18” and then I would be (to them) totally legitimate.

It worked, and they took me, along with a few other kids in the area. However, they scheduled us not to stay in Ohio, but to go west to work on projects. I looked forward to going, and it reflected in my attitude. So I became even more cheerful than I usually was. My father told me many years later that a friend of his was also going into the CCC and hoped that he would run into me somewhere out West. He asked Dad how he would be able to recognize me. My father looked at him, made a face, and said, “You look around and see the guy with the biggest smile on his face. That’ll be him.”

A couple days later, having packed a few things, I left home and boarded a truck along with some other guys, and we headed over to the Akron armory. There we took some tests before they loaded us up and sent us down to Fort Knox, Kentucky. We spent almost two weeks down there, taking classes on what we were going to be doing. Then we were given a lot of shots in both arms. The medics told us that if we got dizzy, to sit down real quick. I started getting light-headed so I sat right down and put my head in between my legs and stayed there until it passed.

After almost two weeks in Fort Knox—they do not let anyone go into their vault to look at all that gold—they loaded us up on trains and we headed west. I had hopped on trains before, but sitting in one was a new experience for me, and I loved it. We sat and watched parts of the country I had never seen before. The weather was great, so the views were fantastic, and I was like a kid in a candy store, watching the world go by.

Yeah, traveling was for me.

We finally made it out to Colorado and I got my first look at the Rockies. I stared at all those big mountains, those mile-high peaks. The train went across some high trestles that were over some really steep gorges. It was kind of scary for me, because we could see down pretty good, and I wasn’t used to that sort of thing.

As the train started up another incline, we went around a bend to the left and saw in the distance another tunnel. Now you have to imagine. We were riding in these old cars that I swear must have been converted from old cattle cars. They were made of cheap wood, with wooden seats and simple thin windows, and that was it. We had found out early in our trip that whenever the train went through a tunnel, breathing became a problem. If you snapped the windows down to open them, then the heavy exhaust fumes from the steam locomotive’s smokestack billowed into the car. We had trouble breathing, and man, all that smoke and soot. If you kept the car windows up, you avoided a lot of the smoke, but not so much the fumes, especially if the car was not airtight.

We had been through a couple dozen tunnels so far in our trip. Now this one we were approaching was called the Moffat Tunnel. We were told it was the longest tunnel in the world—about six miles.3 So we got ready.

We heard the guys in the car in front of us holler, “Tunnel!” So we made sure the windows were up, and then all grabbed for something to breathe through. Those of us with handkerchiefs pulled them out and tied them around their mouths to breathe. I didn’t have one, so I just pulled my shirt over my mouth.

We entered that long dark tunnel. The train was going slower because we were going uphill. We sat there in our seats, struggling to breathe as this black smoke swirled around the tunnel walls, and the windows of our old car, then in through the vents and around us. After a while, I thought that the damn thing would never end.

When we finally made it through the other side, we had tears in our eyes, coughing and hacking from breathing in all that exhaust. Some of the guys were gagging, trying not to throw up. We all saw that we had these dark rings and black grunge all over us. Our faces were dark with soot, some of us so much that all you could make out was the whites of our eyes. But man, it was a relief to finally come out.

After passing through the Rockies, we got off in a town in the middle of nowhere, called Price Utah. It was the closest railroad junction to where we were heading, but still about 120 miles from our final destination, a small town called Vernal, near the border with Colorado.4

Walking around Price in our dirty clothes (compliments of the tunnels), I saw a world of tan. This was the country’s Dust Bowl, created from all the droughts that had recently hit the area. This town was a good example of that. There was just sand and dust. I mean, the streets were paved with brick underneath, but all you could see was this sand. It was everywhere. There were no trees growing anyplace, and I saw no grass to speak of, especially along the highways; certainly not like today. No, it was just miserable.

Dusty and thirsty, a couple of us walked into a drug store and asked the guy at the counter for a drink of water. But the only thing cold that he gave us was his glare as he told us that the only way we could get a drink is if we bought a meal. Well of course, we did not have any money with us. Hell, we were out there to make some. So we had to sit there outside and wait until the trucks came to get us and take us over the mountain.

The trucks finally came, and they loaded us up in the hot sun and drove us to Vernal, a small town of less than two thousand. We were told that this was a friendly town, located on the Outlaw Trail.5 We were driven to our camp, No. 1507, a large compound. Near the front was the mess hall, the officers’ quarters, and a small administration building. Down the center were eight barracks in two rows of four. That was where we would live and sleep. At the back of the compound were the garages, the truck parking lot, tool sheds, and some equipment.6

Because the program was run by the Army, our camp commander was an Army officer. After he gave us a welcome speech, we went to the supply tent, and the supply supervisor looked you over and issued you working clothes. Then we had evening chow, and retired to our quarters.

The next day, we immediately started working on various conservation projects. If we worked away from camp, we took some smaller tents with us, and slept in them. In the hot summer, everywhere we went, we did projects in what seemed like the desert. Things were dry, and the dust bowl stories seemed to be true. I was amazed at how arid everything was, and our soil conservation projects took on new meaning.

For one of our first summer projects, we were tasked to build this small reservoir. The engineer in charge picked a spot where there was a ravine that ran into the Colorado River. We cleared it out and then dug a three-foot hole across the end. A small group of trucks would go off to get clay and bring it in. We then dumped that clay into the ditch, and with these big poles, we stood over that ditch, added water to the clay, and kept mixing it all to build this core about 18 inches wide. That finally stopped the water from seeping.

Then we slowly built the dam and reservoir. Working onsite there in the hot sun, I found out that you did not have to be in prison to bust rocks, because that is exactly what we did. I spent long hours for about a month with these other guys, going around near that streambed, carrying sledge hammers to bust boulders and rocks for what they called riprap7 across the front of our dam.

Out in the heat, our supervisors told us early on to cover our faces, because the sun was pretty harsh on us. Of course, there were some of the kids that wanted to prove that they were, you know, macho, and knew what they were doing. They’d work out in the open with no shirts or caps. The next day or two, they’d wake up with their faces puffed up, their backs and lips all sunburnt. So for relief, the medics would give them Vaseline to put on their backs and lips. And working out in the open, the wind would then blow sand onto their greasy lip sores and create scabs on the mouths of those dummies.

We had a simple routine. Every day except Sunday, we got up real early, made our cots, washed up, and ate breakfast. Then we were either trucked out to the worksite, or walked over if we were out in the field. The CCC provided us all the tools we needed, and the foreman made sure we did the work.

When we were at the camp, we had warm chow for our meals. When we were at a detached site though, warm meals were only for supper. At noon, they would give us a little brown bag. It had in it a sandwich and a piece of fruit. The sandwiches were either cheese or peanut butter and jelly, and the fruit was usually an apple or orange.

Sometimes we would go eat in our tents to get out of the sun and away from the wind. The tents had screen sides, but of course, that did not stop the wind, and with it came the dust. Sometimes it would blow a light coat of sand on our jelly jar, so we would have to scrape the sand off to get to the jelly. That was pretty much all we got, because we had no refrigeration out there. Of course, there was water to drink, but we usually had to haul that out as well, so we would have to watch our intake. Then after lunch and a short rest, we would go back out and work on that dam again.

Because this was a federally funded program, and because we were still in a depression, the pay understandably was small. We were given $30 a month as wages. We got five silver dollars a month. The other $25 went to our families back home.

Whenever we got paid, we were also allowed to buy a CCC coupon book for a dollar. Inside were coupons that you could use to buy stuff cheap at the camp’s canteen, which was a small cubbyhole store inside the mess hall. You could go there during the day and buy stuff like candy, pop, and cigarettes.

Despite the hard work, which I actually enjoyed, being out west was quite the adventure, and I had several interesting encounters with the critters in the area. We were paid little, but back then, a little was worth a lot more. On some Saturdays, when we had the money, we would hitch a ride to downtown Vernal, buy a couple bottles of Muscatel, and try to get drunk. Sometimes on weekends, our excursions went further.

Even though I was a teenager, no one really was picky about age restrictions on drinking, so I was able to get the occasional nip in whatever town we could get to. I remember one time, just for kicks, I walked into a rundown saloon with a small lizard in my shirt pocket. As I sat at the bar, the lizard crept out of my pocket, worked its way down my shirt sleeve, and onto the bar. It raised some eyebrows, but no one thought much about it.

Because I was a likeable fellow, I was able to make friends with the other young guys. Still, the fighting I went through in my pre-teen years paid off, because every once in a while, I would have to defend myself.

I remember one other guy there who for a while wanted to get into it with me. His name was Harold Hosey, and he slept in the cot across from me. It’s funny that I can remember his name after all these years. He was a big old guy of Eastern European decent. Anyway, I had found this snake that seemed friendly, and after I had picked him up and spent the afternoon with it, I had decided to keep it as a pet. It was not deadly or anything, just a simple blow snake.8 They were called that because if they were threatened, they sometimes would rise up, rear back, hiss, and puff their throat and make a blowing noise, like they were getting ready to strike. Of course it was not poisonous, so it was harmless.

The fact that it ticked off the other guys in my barracks just made it more attractive an idea. Harold in particular was really scared of that snake and was paranoid about the thing, and the longer I kept it, the more upset he became. He did whatever he could to stay out of our barracks whenever the snake was in there with me. I enjoyed its company though. I got a kick out of one time where I was walking down between the barracks carrying the snake and this dog came running up to me, barking and carrying on. Well that snake reared back and puffed up and then hissed. That scared the hell out of that dog, and it took off running. I laughed and petted my snake.

Finally, Harold had had enough. He threatened me, telling me that if I didn’t get rid of that snake, he was going to whip my ass, and this and that. Now Harold was about ten years older than me, so that was going to be a problem. Luckily for me though, another guy in the barracks stepped up to defend me, looked at Harold, pointed to his chest, and told him, “Okay, but when you’re through with him, I’m next.” Harold finally backed off, but to make peace with everyone, I eventually let the snake go.

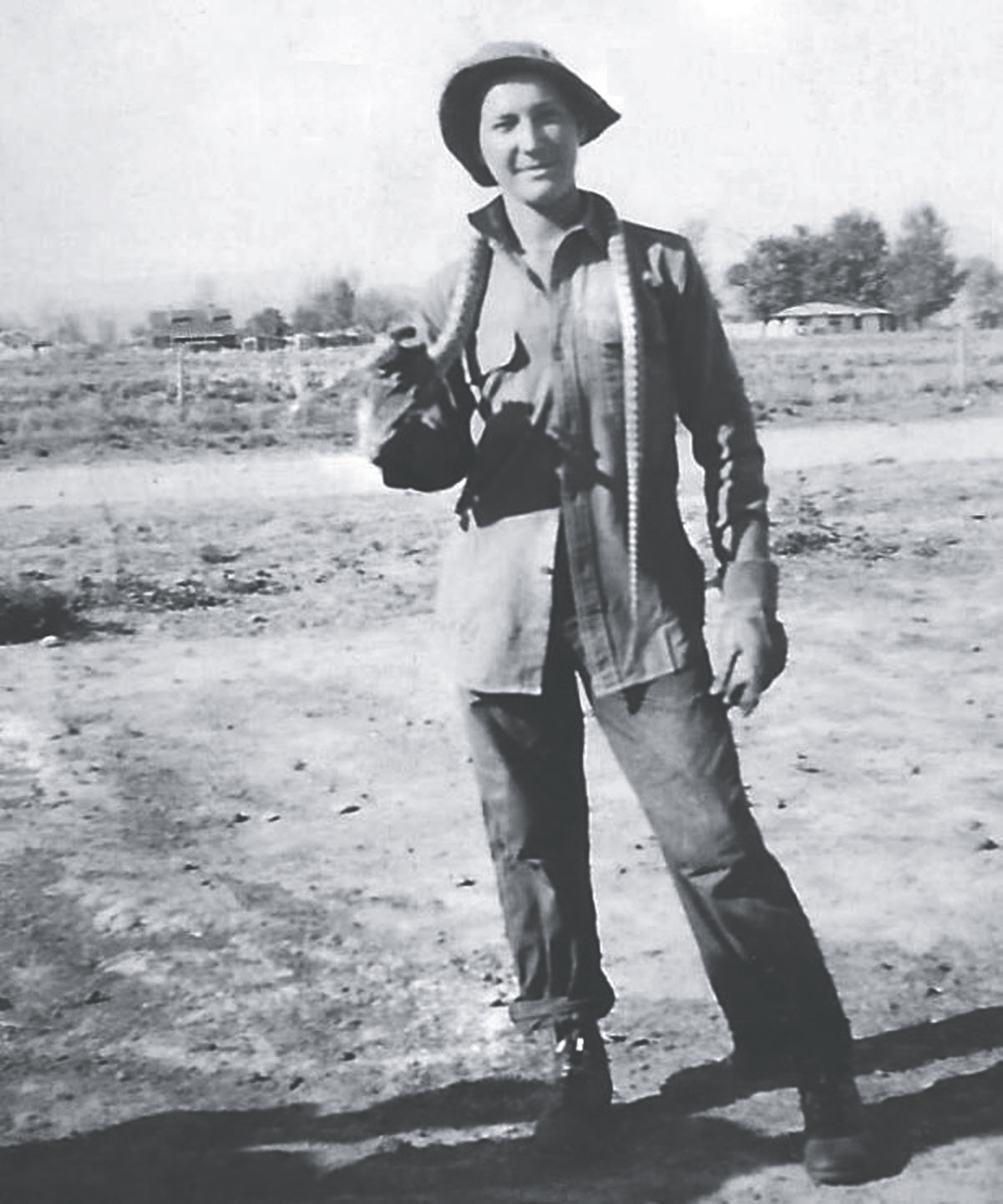

George and his pet snake. Vernal, Utah, 1938. (Author’s collection)

It must have taken us a good part of that summer to finish that reservoir project. No barracks out there. No, we lived in those tents along that ravine, and at a distance, we could see you could see the Blue Mountains, which were a part of the Wasatch Mountain Range. As hot as it was during the day, we could look over to those mountains and see snow on the tops of them.

We worked hard out there, so when my 16th birthday came up on Sunday, September 18th, I figured that I deserved a break. That day, I went into town with three of my friends to celebrate. One of them was a guy named Cotton Drury. He was a fair-skinned lad, and the weather out west was not the best for his complexion. It seemed like his lips were always cracked from the Utah desert’s dry heat, and because his skin suffered a lot in the sun, he looked a lot older than he was. As a matter of fact, for a young guy, he looked older than hell, even though he was 22 years old. Of course, I had only turned 16, so he looked aged to me.

We walked into town, and saw that a few flocks of sheep had come through. There had once been no water in the area; that’s what we built that reservoir for. Now though, the flocks would be driven through town, and that many sheep hitting that little town made quite a mess. When they left, there would be enough dung around to start a fertilizer farm … I mean, they were worse than geese.

We strolled into the town restaurant. Sitting at some of the tables were these sheep herders. That was a common occupation out there, and they would frequently come into town after work, like we did. Between the four of us, we ordered a bottle of our old standby, Muscatel. We had a few drinks and started to loosen up. The guys wished me happy birthday, and I felt good as I sat there slowly getting drunk.

Well, at least until some sheep herder in his late thirties sitting at the table across the aisle from ours started giving us a couple of dirty looks. I took a couple more sips of Muscatel, and looking around, I saw him again staring right at us. He sneered at me and said scornfully, “Look … look at him.”

We stopped talking. As he kept looking at me, he made this nasty grin and said scornfully, “Look at that kid. He oughta be home with his mommy.”

Bastard, I thought. It’s my birthday.

I glared at him and grumbled, “What’d you say?”

He grinned. “You should be home with your mommy.”

I somehow got up, and though I was a little unsteady, I walked over to his table, ready to go. “Get on yer feet, you sonuvabitch,” I said defiantly.

He stood up and I took a swing at him. Cotton, who was standing behind me, also swung his arm and hit the guy dead square in the face. I don’t know where on earth my swing went, but I had clean missed the fellow.

As this stranger staggered back, Cotton grabbed me by the scruff of my neck and shoved me towards the door. “Get the hell OUTA here,” he growled, “before you get in trouble.”

Even though I was drunk, I had sense enough to do what he said. So I staggered towards the door, and propelled myself outside onto the sidewalk. And wouldn’t you just know it, our commander, the guy in charge of our entire CCC camp, was standing there. He was an Army Reserve second lieutenant and holy smokes, I almost ran into him as he stood there in uniform outside the bar. Normally, we never saw the so-and-so around the camp, but here he was now, bigger than life.

He looked down at me with a frown and asked me what I was doing and I told him I was celebrating my birthday. Then I left and went down the road lickety-split, back to camp.

A little while later as it got dark, a couple guys began waking others up. A couple more opened up the property room and began to issue pick handles.

“What’s going on?” I asked.

“The town’s picking on our guys, and you guys are going up to rescue them.”

I was in shock. The other three guys had never made it out the restaurant. Or if they had, there were guys chasing them. The guys finally made it back to camp and the scuffle ended, but I sure did get razzed about it for a couple weeks. How about that, I thought. I’d turned 16 and started my first riot.

After about nine months working with the CCC, I was given a couple weeks of leave. So in March of 1939, I decided that I wanted to take a trip to California and go to the San Francisco World’s Fair that I had heard about. I had a little money saved up, so I took a Greyhound bus and headed west. By the time the bus passed into Nevada, it was evening. We went along in the dark, seeing nothing but the road ahead and the night sky.

Then we began to see swarms of locusts hopping on the road and along the roadsides, and as we traveled, their numbers intensified. We had evidently run into some sort of a giant infestation. The more we went on, the thicker the swarm, and soon the bus began sliding back and forth along the road because of all the squished insects in the bus’s tire treads and under the wheels. I had never seen anything like this before, and I just sat in my seat in wonder, shaking my head, amazed at so many thousands of these insects that were flying and jiggling and hopping all around the bus.

Driving became difficult, first to navigate, and second just to see the road. Finally, the driver had to pull off. We stayed there, watching these hordes wildly jumping around. They crawled all over the outside of the bus, and the windows were so thick with them, we could barely see the sides of the road. The biggest part of the swarm finally began to move on, and as the swarms thinned, the driver started the bus, and we continued on.

When we finally pulled into Reno, the bus took a couple hours’ delay. As was my nature, I took a walk around the town exploring. One thing I wanted to see was the casinos.9 I had never seen a professional gambling strip, and as I walked past the nightclubs, I saw sights that left me amazed. In those days, the casinos had lots of neon lights outside and all sorts of lamps inside, and these huge glass windows that let passersby stop and gaze in. Poor kid that I was, I was one of the biggest gawkers.

Each establishment had a number of gambling tables where all these people were playing cards, or roulette or throwing dice. I was amazed at all the stacks of money lying around. In those days, the casinos did not use chips. They only used silver dollars.

The bus continued on to San Francisco. There I went over to the World’s Fair and managed to get a temporary job working odd tasks. I was paid little, but during that time, I got fed and free attendance to most of the features there, including the famous attractions. One thing I really enjoyed was watching a performance of Sally Rand,10 even though I was only 16 years old. Her performance was a hit, and I really got a kick out of watching her glide across the stage.

Something that first surprised me was the number of gay guys around. You have to realize that back in 1939, that was a rather shunned practice, and in my life, I had never really been exposed to that sort of thing. Around San Francisco though, I was given a real experience. I guess the image of this fresh young smiling tourist teenager walking around was the sort of thing that appealed to them, or perhaps they thought that being with a guy appealed to me. At any rate, they would often pester me.

There was this bar on Broad Street called Dorsham’s. I went in there on the first day in town. I happened to be wearing a cheap bowtie that I had found. To my surprise, a couple of guys tried to hit on me, and I could not figure out why. When the third one made a pass, I asked him what in blazes was going on. He finally told me that the bowtie was some kind of secret signal to other guys that I was gay. I immediately stood up and left that bar. Going outside, I ripped off my bowtie. I ain’t worn one since.

I worked at the World’s Fair a couple weeks or so and while I was there, I met a couple guys working like me. We talked about the dangers that this city seemed to have, so we decided to stick together for protection. The three of us left there at the end of the second day of work and took a streetcar to downtown San Francisco. We ended up going to Chinatown, because we had been told that you could get a room there cheap. I had to admit though, that the area made me kind of nervous. For one thing, there were some gruff, scary-looking people there, and a lot of them gave us some really cold, mean looks. Another thing was that I was not used to being in an environment where no one spoke any English.

We rented a cheap flop over some restaurant and while we were there, we hung out as a group. To be honest, we were afraid of them damn Chinese. We had visions of these short, fanatical Oriental guys in them black silk suits screaming and running around chasing us with hatchets. Needless to say, we were really leery being there.

I finally started back to my CCC assignment in Utah. It took a couple days to get there, hitchhiking along the only available route at the time, U.S. Highway 40. I got back to Venal and back to work on locations far from any civilization. We always worked out in the middle of nowhere, dozens of miles away from even the smallest town, and it was always cold as hell out there, even though April was upon us.

One time, we went south to do a project near the Ouray Indian Reservation.11 I was really surprised at how they lived. For one thing, their village was made up of these really small, low hutches made out of this molded adobe clay. Hell, I could stand next to one, and as short as I was, I could see right over it. They were like bowls in the ground. Still, they ate and slept in them, and you could see smoke coming out of some of them. We were told that these were the Ute Indians (pronounced “You-tay” but I called them “Yutes”). We drove through the reservation, crossed the Green River near Colorado, and kept driving way out into the damn desert. It was dark when the truck stopped. All 35 of us were told to get out, and to start pitching tents and to set up a spike camp.12

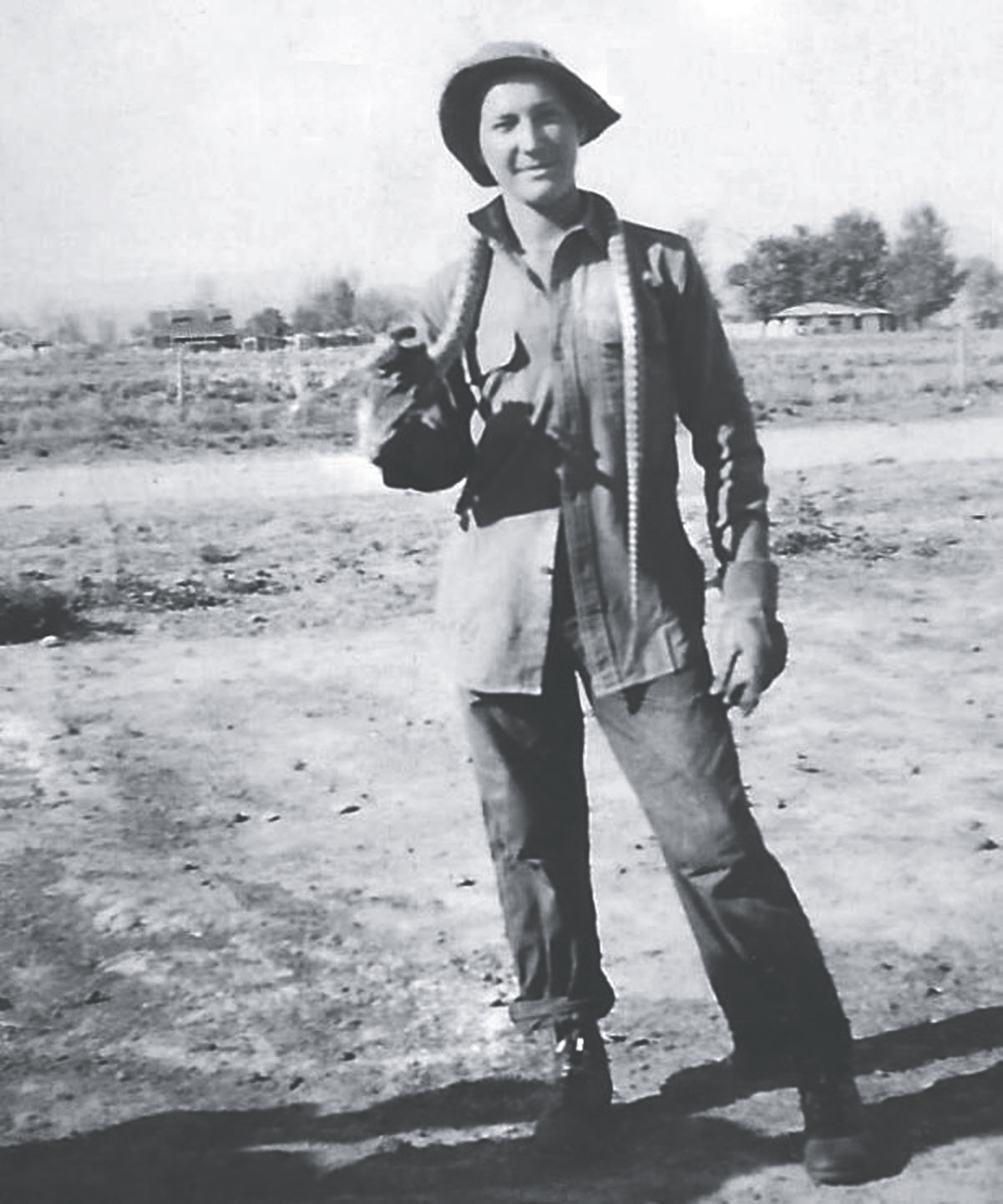

George’s CCC spike camp in Utah, fall of 1938. (Author’s collection)

We used fallen logs for fire, and for water we brought our own, because there was none out there—we had a 500-gallon tank strapped onto the back of one of our three trucks.

We ended up working in that area for some three months. We moved our location once in a while, and so we saw more of those Ute Indians. I remember one time during the day, we went out and crossed the Green River, which is a lot wider than people think. As we started driving along the river, about 200 yards to our left were all these Indian women doing their laundry at the river’s edge. There must have been twenty or thirty of them standing there, bent over washing clothes. As we came closer, they looked up and saw our small convoy coming down the road. I don’t suppose that they had seen many people like us, so the sight of our trucks must have scared the crap out of them, because they quickly grabbed their wet buckskins and began running up the bank. Our trucks slowed down and we watched as these Indian gals ran like the devil was chasing them, back up the slopes and off to their village in the distance. Obviously, they were really terrified of us. I guess they had a right to be.

At night, tired, we would come in from a long day of work, eat, fool around for a bit, and then get ready for bed. We slept about four guys to each tent. Before you hit the sack, because the wind blew that sand everywhere, you had to scoop the sand off your cot before you crawled in.

There were some bad guys in the camp, guys that had seen the harder side of life and often seemed to have a chip on their shoulders. But we mostly avoided them, and sooner or later, most of them became outsiders, and eventually outcasts who left the CCC. Things were different back then. We all looked after each other, especially way out in the middle of nowhere. We formed our own little social groups, and then we often hung out together. Back then things were simple and not complex like they are today. Folks just looked after one another. We just kind of ruled ourselves. Nowadays, if people see someone dying on the street, they are apt to just ignore them and walk away. It pretty much wasn’t like that back then, and the older ones made sure the younger ones were okay. I guess that in many ways, it was also a good time as well, and in some ways, a good time to live, a good time to grow up, as compared to the 21st century. People say that oh, those were tough times back then. But you know, by God, I wouldn’t trade them for this kind of life today. Life was pretty uncomplicated. We didn’t have all these fancy play toys that they have now. We didn’t have anything. The work was hard, too, although I was in shape for it.

A second lieutenant ran the camp. We rarely saw him around though, except for formal ceremonies. The foreman in charge was an okay guy, although he could be a bearcat sometimes. He was just a civilian though, and he didn’t have any authority over us. So his two army assistants were the authority. The leader was a husky sergeant, and the assistant a corporal.

I remember one Sunday sitting in our tents, grumbling about our lives. We had run out of fresh water. The worksite had a shallow well, and we could draw water out of it with this little pump. It was okay to wash with, but other than that, yech! It tasted horrible. It had a strong alkali base, and you couldn’t drink it without getting nauseous. The water shortage, the working conditions, being out in the middle of nowhere, and the fact that they were really pushing us—all of this made us decide that afternoon to do something about our conditions.

We decided to go on strike. On Monday morning, when they blew the whistle for work, no one was to go out of their tent. We all agreed and spread the word: no one would do any work until our conditions improved. Sure enough, the next day, at 10 a.m., the foreman and his two assistants stood outside. The “485” (the sergeant) blew the whistle, and nothing happened. Nobody showed up. We all sat in our tents and waited.

He blew the whistle again. Again, nothing. So he stuck the whistle in his shirt pocket and walked over to the first tent. The rest of us got up and cautiously peaked out. He strode into the first tent and disappeared. After a few moments, here came four bodies flying out of the tent—zoom, zoom, zoom, zoom. They sailed out onto the dusty ground. Then the 485 came out of the tent and started bellowing. Wow, the center lane filled up with all of us ready to work.

That pretty much ended the strike.

As the weeks went on, we worked a number of projects. Our evenings were usually dull. We often boxed, sometimes until it was nearly daylight. That was about all we had to do. There was no recreation area, no horseshoe pits—nothing way out where we were. Once in a while, we went exploring, although we had to be careful, because there were snakes out there. Now and then, just out of boredom, we’d go out and chase jack rabbits and try to get them with just a rock. At night, if we were bold enough, we would take flashlights and go off hunting rattlesnakes. I never did that, but sometimes I would go just to watch.

If we were feeling bold, a couple of us would go on a raiding party. One night, not satisfied with the lousy meal that they had served, I and another guy decided to break into the back of the storage truck they were using as the pantry. We picked the lock and opened the truck door. In the back, we found several gallon cans of peaches and pears. We carefully grabbed a couple cans of peaches, tiptoed away from the parked truck, and took our cans down to a nearby gully.

We opened the cans, and with big spoons we had brought along, we began wolfing down those stolen peaches. Man oh man, did they taste good. We sat there in the gully in the dark, gorging on those sweet, juicy chunks. We made some disgusting slopping noises as we bolted our prizes, but of course, not loud enough to draw any attention from anyone in the camp.

We were having a great time until suddenly I heard a rattle nearby. I stopped and held up a hand to get my buddy’s attention. He stopped eating and we looked at each other, listening.

There. There it was again—a faint but deadly sounding rattle. We of course assumed it was a rattlesnake. Man, we threw those cans up off our laps took off running back to our tents, and that was the end of that. The next morning the camp foreman and his guys tried to find out who had broken into the food truck. Thankfully, they never caught us; we had gotten away with that. It was a freebie.

We finished our projects in the late fall of 1938, and I was surprised when they then took us up into the mountains. We got up to such a high elevation that we reached parts covered with snow. We could actually walk in chest-deep snow to make a path. Then the sun would come out and hit it, and it would get so warm many of us would take our shirts off and get sunburnt from the rays reflecting off the snow.

The new projects were varied and interesting. We worked on roads and built cattle corrals on ranches using pine tree trunks that we had to saw the ends off. We put in wooden irrigation systems, and put up or repaired all types of fences. One of the toughest projects we did was putting up a ten-mile drift fence that went up and down cliffs and along the side of a mountain. It was hard work, and sometimes we had to put the fence up through solid rock.

The trucks would drive us to where they wanted the fence poles. The roads were at best gravel paths, so riding around up and down those mountains was a real experience. The truck would go along for a while, then drop two guys off. Each pair would scout around for a short low cedar tree and chop it down with these double-bladed axes. We would cut the ends off, carry it back to the road, and then go out for another one. Later on, the truck would come around and load the trunks up to take them off to be sawed down into fence poles.

Working on those wide open slopes during the day was quite the experience. Whenever I took a break, I would walk on top of a nice high hill for a great panoramic view. On a clear day, I could look out for what I thought was a hundred miles. And what would I see? Just about nothing but desert. Sometimes, munching on my sandwich, I might see far off in the distance some wild horses running, playing, nibbling on some shrubs. I’d sigh and smile as I watched them. Life at that point seemed great.

The grass grows high up in the mountains, and it gets thick and green in the summertime. Since there is nothing but desert below, the ranchers sometimes drove their cattle up to graze on this government land. So we built ten miles of that fence through those mountains to guide the cattle. Sometimes that fence went straight down to the bottom of a gorge.

I finally got the job of stretching the barbed wire for the fencing. I had a come-a-long with a pulley. I would hook it onto the fence post and using the jaws on the other end, I would tighten the wire from one pole to the next so that the other guys could then nail it down. I also had a big empty 50-gallon drum at the site in which I kept a fire going, so that we could stay warm. The guys hauled the wood up and I kept the fire going, as well as pulling up the slack with the come-a-long. I would say that all in all, I had a pretty good job.

We stayed up in the mountains on and off the whole winter. It snowed heavily, and a few times there would come a heavy snowstorm that pretty much brought most of the work to a standstill.

Back east

I finished my stretch in Vernal and came back to Ohio. Employment with the government CCC was a two-year contract, and the way the program was set up, if you worked for them for one full year away from home, for the second year, they would relocate you to a project somewhere in your own state. In June of 1939, now entering into my second CCC project, I was assigned to a farm near Fresno, Ohio, about 10 miles northeast of Coshocton, and just 60 miles from where I had grown up at Portage Lakes.

The farm was a huge government project.13 There were about 15 of us from the CCC working there, along with other construction workers and engineers. My main job was to take charge of these beautiful Percheron horses.14 I had never been around horses like this, so I enjoyed taking care of them. Not only were they beautiful, but they were friendly and easy to work with.

With a couple assistants, we strapped plows to the back of these wonderful animals and did a sort of excavation by digging out this large hole in the ground for the basement of a chemical lab to be built there. I also at times hitched one up to a wagon and hauled wheat around, for consumption by both the horses and us. To collect and process the wheat though, we used this huge combine to harvest it. It took about a dozen of us to work it. Afterwards, my buddy and I stood in the rafter of this huge barn, with the combine just below us, and we would feed that thing for hours at a time.

Whenever I had some spare time, I wrote home. I found out one day in a letter from Mom that Waddy’s girl Donna had died of some weird disease, and I felt bad for her family. That night, I remembered the good times Waddy and I had shared with her. It bothered me that someone so close had passed away.

I could not know that this would happen a lot over six more decades.

Working with the Percherons was enjoyable, but towards the end of my tour, another half dozen horses came to us, and these animals were not as high bred. They were just pathetic-looking. These, we were told, were army rejects, and we were to make the best use of them that we could on the farm.

Riding the army horses was okay I guess, but they were not as enjoyable as the Percherons. I remember that there was one army horse that was in much better physical shape than the others, but had a wild streak in him and could never be broken. But I had a wild streak in me, too, so I took this as a personal challenge, and decided to put this steed to the test. One of us was going to break, and I decided that it was not going to be me.

With my co-workers watching in amusement—a couple bets I think had been made—I took the animal to a 20-acre pasture and mounted a saddle on him. I steadied the horse, looked over at my buddies, and with a bit of a jump, I mounted him.

The horse immediately reacted. It bucked a couple of times, then took off pell-mell across the field. I held on for dear life as the horse made a dead run all the way to the end of the pasture. It then immediately whirled around and came back at full speed. Again, I held on tightly, wondering how this was going to end. My eyes watered to the point where my vision became blurred as the wind whipped around my face.

As we raced across the pasture, I saw the open gate coming up fast. Unfortunately, the horse’s eyes must have watered and blurred too, because he missed the gate and ran headlong into the barbed-wire fence. The strands caught him in the chest and ripped open a deep gash as he fell heavily. I was thrown and went sailing over him, hitting the ground and rolling roughly.

Slowly, I got back on my feet, dizzy as hell. As I recovered, my co-workers went over to the horse, thrashing about, and freed him from the fence. I recovered, but the horse was in pain from the wound, and eventually the veterinarian had to put it down.

After several months working on that farm, I decided to return to high school. It was autumn of 1939 when I went back. I started attending Kenmore High in Akron. I was 17 by then, and I wanted to complete my second year of high school. On the first day, I was lucky enough to meet this lovely young lady.

That morning, along with my buddy Richard Tomkins, I was sitting out front waiting for the bell to ring, when this cute little gal walked passed us. She was a bit on the slim side, but well proportioned, and to me, absolutely gorgeous. The short skirt she was wearing only highlighted her nice build.

I just shook my head and mumbled, “Damn, I’d love to get to know her.”

Richard filled me in. “Oh, she’s Phyllis Carpenter, and she’s related to such and such.”

Still staring at her, I said, “Uh huh …”

Richard replied, “Yeah.”

I said, “She’s pretty. You know, I’d sure like to take that girl out.”

Richard grinned and said, “You know, I could arrange that!”

I looked at him. “Yeah?”

Richard stood up and said, “C’mon. I’ll introduce ya.”

We grabbed our stuff and, walking rapidly, we caught up to her. Richard introduced me, and although I was a little embarrassed, we starting talking.

In the weeks after, I did whatever I could to get to know her better. Surprisingly, she took a liking to me. We finally started going together. We would go steady together on and off for the next seven years.

While I was in the Marine Corps, she wrote letters to me, and as the family got to know her, she would occasionally visit them. She even took a short summer trip with my mom. Phyllis and I did a lot together. Yeah, she was my steady girl. If I went somewhere with a bunch of guys and she could fit in, she would go along. Things like swimming jaunts and going into town. She was sort of like my right hand.

All during that time, people just accepted the fact that she and I were paired. I guess that during that time, I dated a few other women, but Phyllis never knew about most of them, and those that she found about, she did not seem to mind much. I guess that she figured that she had me hooked, so there was no need to worry about me finding another love. Strangely though, we never talked about the future, about getting married, probably because she knew my views on that. I had absolutely no intention of getting hooked until I had sowed my wild outs and the war was over. However, I did resolve to make a thorough inventory of the female species, so I decided that I would date a lot.

I continued that second year of high school. Some subjects I did okay in. Others, not so much. History was my favorite. Chemistry I hated. Music though, was the worst. For me, it was a disaster, and each year, I would get a big red F—not that my teachers hadn’t tried. This year was no different, and in the first week, as we sang, our music teacher would walk behind us while we were singing and listen to us. Finally one day after class, she called me aside and told me that she wanted to work with me on my music abilities to improve my grade. We went over to the piano. First, she told me that she was going to play one note and then a second one. She said, “You tell me whether I’m going up or down the scale.”

I tried, but I guess I didn’t do so good. Then she told me to try to sing each note after she played that key on the piano. I tried to sing each one, but I just could not do that either. We did this for a while, with her banging out a note, and me screeching out what I thought was the equivalent. Finally she stopped, shook her head and said to me, “You know what? You’re tone deaf.”

I thought she was crazy, but I didn’t say anything. I just stood there.

Feeling sorry for me, she said, “I’ll tell you what I’m going to do. I’m going to make you a deal. If you promise not to sing in class or in any of the concerts, and you behave and do the written work, I’ll pass you.”

I did what she asked. When it was time for the class to sing, I would either stay silent or just mouth the words. She turned out to be true to her word and gave me a D. I was happy, because that was the first time in music that I had not failed. When she had offered me this deal, I had initially thought she was nuts about my musical talents. Look, I knew I was no Bing Crosby, but on the other hand, I didn’t think I was really that bad. Over time though, I finally realized that apparently she had been right. I guess after all it did not turn out to be a big deal, and I have learned to live with it. I was just not musically inclined, and after that, I never did have much use for music.

As a boy, I had naturally always been fascinated with cars. The first one I remember Pop having was this old black Model-T Ford. The battery was not worth a damn (and batteries were expensive), so to start it, he had two choices. He could push it down a hill, pop the clutch, and hope that it started right up, or he could use a hand crank on the engine, which in turn had its own dangers. For one thing, sometimes the clutch would not completely disengage, so when the car began to start, you could find yourself getting run over. Second, if you tried to hand-crank the engine and the spark was not set to the ‘retard’ position, when the engine caught, if you did not pull the crank out, the engine would yank it around. If you were holding the lever firmly at that point, the force could sprain or even break your wrist. I remember my father on many cold mornings, out there in the snow, cursing and muttering as he cranked over that damn cold engine.

And of course, the entire experience was even more dangerous when the old man had been drinking. Once when I was about eight, half drunk and running out of booze, he decided that he was going to go out and get more. He always liked someone to go with him, and so he looked at me and told me that I was going too.

As big as he seemed to me and as small as I was, I knew better. I stood up, looked right back at him defiantly, and said, “I ain’t goin’ nowhere with you the way you are.”

He glared at me and said, “What!” Insolence from any of his kids was something he did not tolerate.

I looked back at him, scared but determined, and said, “I ain’t goin’ with you.”

He thought about that (as best he could in his condition), nodded, turned to my older brother Alex, and told him that HE was going to go with him. Al was sort of easy going and did not have the nerve to turn Pop down, so he gave in, and after the old man managed to get the car started, they took off.

I guess Pop was drunker than he thought, because they did not get very far. He drove right through an intersection on Manchester Road and hit another car. The Model-T was totaled; I mean it was gone. And Al was thrown into the windshield. Now you have to remember, the glass on cars in them days was not safety-rated like today, and so the glass splintered into a thousand pieces. One of those slivers went into Al’s neck and nearly killed him. If the piece had penetrated a half inch over, it would have severed his artery, and he would have bled to death right there.

The police were called to the scene, and the next thing we knew, a squad car pulled up to the house. The cops told mom, “Your husband was involved in an accident, and your son has been taken to the hospital.”

Jesus, what a jolt that was for mom. Well, Alex recovered, and though the old man was charged and had to appear before a judge, he never had to go to jail. Part of the reason I am sure was his position as an interpreter for Judge Hunsicker. I think that did get him out of a lot of stuff.

My fascination for wheels continued. As kids, we sometimes rode the bumpers of cars or better yet, trucks. Yeah, back then, our motto was anything that moved was fair game for us. We would often stand near an intersection, and when a car approached and stopped, we might run to the back of the car, sit on the bumper, and ride like that for several blocks. Of course, that was not without the obvious dangers. Finally, when I was about 12, the car I was riding on turned and I went sprawling onto the black gravel road. My knees were skinned and I had a couple serious cuts on my left hand. That put the end to that type of stunt for me.

As the years went on, both my father and my older brother managed to get their own cars. Aged 13, I resolved I was going to get in one and take my first drive ever. So one day, when no one was around but me, I went over to Alex’s car and managed to start it up. I got in, put it in low gear, and took off up Wingate Road. Ahead I could see the Waterloo intersection approaching. I was happy as all get out. I was driving!

When I approached the intersection, I tried to shift gears, but I was no good at it, and the car stalled and died. Determined to keep going, I started it again in low gear. When I tried to shift though, I stalled it again. I started the car again and made it to the end of the road. I managed to turn around and start back. No matter what I did, I could not get the damn thing out of low, and every time I got enough nerve to shift, it stalled out. So finally I drove it back to where it had been parked, never getting out of low gear. When I finally turned it off, I could tell that transmission was really hot. Of course, I never said anything to anybody, and luckily, nothing on it had broken down.

I finally bought my first car after I returned from the CCC. I was 17 years old living in Wooster in the fall of 1939. My prize was a 1929 Ford with a rumble seat, and I paid $30 for it, which seems dirt cheap today, but back then, was a lot for a kid like me. I did not keep it too long, and soon traded up for something much better to travel back and forth from Wooster. My second vehicle was this beautiful tan 1932 Model-A Ford convertible, complete with these big hubcaps. And I got it really cheap; I only had to pay $35 for it. Of course it needed some work, and I often found myself pushing it to get it started.

Like that one time Mom got herself a short little unexpected joyride.

I had been working on the car that morning, and now I needed to start it. Of course, the battery was no good on it, so it would have to be push-started. I could do the pushing, but I needed someone else to steer and to start the engine when it got going. The only one at home was Mom, and she had never driven a car in her life. That did not stop me though, and I finally persuaded her to reluctantly assist.

The car was sitting on a gravel road near the top of this hill. The road had a downward slope before it turned into our drive. There the slope became steeper, and finally bottomed out in a creek.

Mom got in the driver’s side, mumbling “I’ve never driven a car in my life.”

I turned on the ignition key for her, closed her door and then told her, “Mom, I gotta push this damn thing, but I gotta have you in there.”

So I set the magneto and explained the clutch pedal to her. I told her that when I gave her the word, she was to engage the clutch again with her left foot, and when I shouted “Okay, now!” to pop the clutch to put the engine in gear. I said when the engine started, to push the throttle adjustment lever on the right upward to idle the engine. She looked confused, but she said she thought she understood.

I got behind the car, and gave her the word to step on the clutch. She did, and I began to push the car downhill. It began to pick up speed, and when it was going about ten miles per hour, I shouted, “Okay, now!”

Mom popped the clutch and the engine started. I shouted for her to move the throttle. Mom though, instead of pushing up on the lever to idle, pushed it down—driving mode—and with the extra gas to the engine, the car took off down the slope, leaving me standing there in the middle of the road. I began running after the car, shouting and waving my hands, while Mom, desperately trying to steer, yelled back, “What do I do NOW?”

The car kept going, now moving at a good clip, but mercifully, my mother had enough foresight to turn the wheel into our gravel drive; a good thing, because if she had not, after a block or so, she would have gone right into the Ohio Canal.

The car continued down our drive to the bottom of the hill and with a whoosh, drove right into that creek. The Model-A went right across the creek bed, throwing up water on both sides. As it started rolling up our driveway, it thankfully stalled. As I ran up the driveway, Mom slowly got out, soaked and looked shaken. She had had the crap scared out of her, but she began laughing her head off. I mean, I don’t think I ever saw her laughing so hard. I came up to her, started laughing too, and hugged her, glad that she was still in one piece.

Finally she looked at me and, shaking her head, she said, “Never again, George. Never again.”

Now Waddy had this big old junker that looked like a convertible gangster car. My brother Al had somehow been able to buy an old four-door sedan, and I of course had my tan ’32 Model-A with the big hubcaps. This one day, feeling daring, the three of us took off racing east down Carnegie Avenue, roaring towards that little bridge that went over and onto the hotel, our cars abreast of each other. Naturally, it was a race, and we were all wide open, with these three cars side by each, headed pell-mell down that dusty, gravel road towards this bridge that was only two cars wide. Because the bridge was arched, you could not see if another car was coming your way. If one was, there would be a crash.

I was in the middle, so I was pretty much committed, whether I wanted to be or not. Thank God, no one was coming the other way, and so Waddy on the right and I both made it over the bridge. Alex, though, was on the left and about ten feet back, and began to realize that he was not going to make it and was about to smash into the metal abutment on the side of the bridge. So at the last second, he veered off. Unable to stop in time, he and his car flew headlong into Nesmuth Lake with a big splash.

Luckily for him, he did not go in too far, and it was still shallow where the car stopped. His motor though, was well underwater. Always ready for a breakdown though, we all carried rope and stuff with us, because none of us could afford a tow. So Waddy and I drove back, hooked up the rope to each side of Alex’s rear bumper, and slowly pulled the car out of the lake.

We figured that the hotel people must have seen the crash; hell, it happened in plain sight. But they never came out to yell at us, and as far as we knew, the police were never called. Not that we would have given a damn. What the hell. We were kids. Of course, on the other hand, we were smart enough to not stay around. So we towed Alex’s dripping car back to our place, and a few days later, he actually had the damn thing running again. Of course, the cushions were soaked and took a long time to dry out.

I will say, though, we did our best to maintain our cars. It seemed like we were almost always working on them. The cost of running them was expensive, although fuel was cheap in those days. I remember there was this filling station on Route 76, coming into Barberton off Highway 224. Gas there was two gallons for a quarter. Then after I got our gas, I would walk over to the pit that the repairman stood in to change the oil on a car. In the pit was this barrel that he used to drain the oil. I would go down into the pit, grab the bucket down there, and dip it in the barrel. The owner did not mind, and it was free oil for me.

I still had another half year to go in the CCC. I was assigned to Camp Anthony Wayne, just outside of Wooster, Ohio in the fall of 1939.15 I continued my education. I took several courses at night school, included typing. I kept dating Phyllis, and though she lived in Akron and I was in Wooster, we saw each other a lot. Either she would come over and visit me, or I would go home and see her. In fact, I was at her place as much as I was at mine, and she came to my house anytime she wanted. In the meantime, I sometimes dated other girls, but I don’t think she ever dated another guy in all those seven years.

During the day, because I had a chauffeur license, I served as our crew’s driver, taking us to and from the locations in an old truck. Every day, I hauled some 35 guys out to that day’s work site. We helped farmers learn how to strip crop over hilly country to keep water erosion down. We helped build a government conservation laboratory (which is still there today, doing soil conservation services). Once in a while, I was allowed to run a hydraulic jackhammer to help dig these huge craters.

I was also the crew’s official blaster, since I had certified explosives training in Utah and certified to give first aid, as indicated by my Red Cross card (which I carried in addition to my dynamite blasting card and my chauffeur license). Driving the crew to a site every day. I’d bring the dynamite and the blasting caps, setting them in the front seat with me, and driving as carefully as I could (all of course, which was illegal, but I didn’t know where else the hell to put them).

Our job was to clear fields with explosives as needed by blasting stumps and big rocks. For a large boulder I would secure the dynamite sticks to the top of the rock, run two wires into the bundle, and then cover them up with a thick mud pack. I then ran the wires back into the battery detonator and hooked them up to the terminals. Making sure everyone was clear, I would give the warning and then set off the charge. Because of the thick mud layer, a large part of the force of the explosion would be directed downward and would split the rock. After that, it was simply a matter of hauling the chunks away.

Tree stumps I treated differently, depending on their size. For the big ones, I usually planted the dynamite below the stump. I remember one time we had to clear the stump of this monster of a tree. The stump itself was tall, and had a massive girth. Up to the task, I planted 20 sticks under the stump, setting them in at a slight angle. My helpers put out the word, and a local deputy even had stopped traffic along a nearby road while I prepared. I ran the two wires to the detonator as always. I checked the sticks once more, making sure everything was set up correctly. I came back to the detonator and connected the two wires to each terminal. With the circuit live, I shouted the word to everyone around to stand clear. Finally, I pushed in the plunger, and the dynamite exploded. I watched in wonder at what I saw. With that many sticks, that entire massive stump went up ten feet into the air. My eyes wide, I could not help but think that it looked like a huge dirty molar, roots and all. Quite unforgettable.

By the summer of 1940, World War II was well underway. I knew that someday I would be drawn into the military, whether I wanted to or not. War was on the horizon. Europe was in the middle of it, and everyone in America knew that sooner or later, one way or another, we would become involved in it. The military was already starting to expand, and factories were gearing up production. No, war was coming.

So with all this in my mind, I began to think about joining the service. I was certainly no keen patriot. Still, the service had its advantages. For one thing, the steady pay and food was appealing to a dirt-poor boy like me. More than that, I guess that my desire to travel instilled in me a hankering for some real adventure. I was like that—rambunctious and antsy.

I was in Wooster with my last CCC hitch coming up. It was September 1940. I convinced a buddy of mine that it would be great for him too. We got permission from our parents to join, so together one day, we hitchhiked up to Cleveland and walked into a recruiting office to sign up. I wanted to be a Marine.

We talked to the recruiter, some guy in an immaculate, sharp uniform, and we liked what we heard. So we talked it over and decided to join. We signed the preliminary papers, and everything was going fine until we went through the standard physical qualification examinations. We were both in great health, and I passed with flying colors. Unfortunately though, my buddy failed the eye examination because he was color blind. Thinking about it, I decided that I did not want to go into the service alone, so we reluctantly left. It was too late to go home, so we stayed overnight. We were too poor to rent a room or find a cheap boarding house, so we went over to the Cleveland jail and spent the night in one of their cells.16 It was the first time for me doing that, but it would not be the last. The next day, we returned to Wooster.

Shortly after that, I relocated up to Akron and moved into Alex’s apartment at 2273 17th Street in Akron. My first job was with the Troy Laundry Company. I busted my ass 12 hours a day for just 25 cents an hour. Then because I had a chauffeur license, I got a job driving a truck during the day. I helped out at a bar part-time at night. Normally you have to be at least 21 to do that, but since my chauffeur license indicated that I was, I qualified—even though I had just turned 18.

I spent the rest of the winter of 1940 there in Akron living in an apartment with Alex. I worked odd jobs and in general just hung out. I then became a self-employed truck driver for this Greek who owned a trucking firm called the Hanna Trucking Company. He had three old broken-down trucks, and I got a job driving one of them. As a freelancer, my job was to park the truck every day in this lot and wait. If a job came in, I would have work. If one did not, I did not, and so I was not paid.

One night, my truck broke down, and the Greek, knowing that I needed the money and that as a good driver he might lose me to a real job, asked me if I wanted a second job, to assist his daughter. They owned this small bar located on the southeast corner of Highway 93 and Kenmore Boulevard, and his daughter ran it at night. She needed someone that night, and could I help out—that is, if I could tend bar. Sure I could, I told him. What the hell. A job is a job.

He took me over to the bar, introduced me to his daughter, told me what I would be doing, and left. She and I hit it off right away, and together, we started working that bar at night. Although she was a short brunette, she was really built. I mean, like a real Greek goddess. Naturally, I began to flirt with her from time to time, but she decided right away that since she was older than me by a few years, that I was too young for her. I tried a couple of times to score with this sweetie, but no success.

I worked at the bar for about a month while my truck was being repaired. When it was fixed, I assumed that I would go back on the road. The Greek though, wanted me to keep tending the bar. He liked me, evidently. It was a good thing that he did not know that I was after his daughter.

Finally I confessed and told the Greek that I was really only 17 years old, and not 21 like he had assumed. He was shocked, replying, “My God! I didn’t know that!” So I had to go back to driving again, and that is how my days passed during those cold winter months. I went back to freelance truck hauling by day—when the piece of crap did not break down—and some going out at night on my meager pay. In the meantime, the Marine Corps kept sending me enlistment brochures, and I read about how awesome it would be to be a part of the greatest military service on earth.

Seattle bound

By March of 1941, World War II was into its second year, and the Axis reigned supreme. With the exception of Great Britain bravely standing alone, the rest of Western Europe had fallen. Greece and Yugoslavia were about to go down as well. Most of the Baltic and Eastern European countries were either aligned with the Third Reich or were about to be. In the Pacific, Japan was winning its war of aggression against China. Korea, the Marianas, the Carolinas, and the Marshall Islands were all now Japanese territories. French Indochina had been invaded in 1940, and Japan was now becoming bolder in its claims for a new Pacific empire. Tensions with the United States were mounting, and an American embargo would only promise to bring the economic confrontation to a head within a year.

In the spring of 1941, wanderlust got the better of me. Generally unhappy, I decided to quit my truck-driving job and head out west. I was disgusted with my life, the weather was cold, and I was driving that miserable, unreliable old dump truck as a part-time freelancer for that grouchy Greek. When I was not hauling around gravel and asphalt, I was sitting for hours in the Greek’s office shack or in my truck waiting for another assignment so that I could get paid—not that I was getting that much. No, I needed a change in my life.

My plan was to make my way to Seattle, Washington, get a job on a luxury liner, and hook up with some rich broad. I asked Alex if he wanted to go too. I figured we could really have a blast out there, schmoozing with a couple of rich babes. Alex declined though. So, disgusted with the dump truck that I was driving, the nasty, smelly asphalt, and the lousy pay, on a cold, rainy morning, alone, I left Akron and headed west. Strangely though, two weeks later, Alex decided to take off and go west too.

Without even bothering to quit my job, I just left Akron. I hitchhiked across the top of the country, determined to get to Seattle. Early on I got a ride from a guy driving another gravel truck. He picked me up on U.S. Route 30. He was headed northward into Wisconsin, and then westward from there. So I nonchalantly tossed my suitcase in the back, on top of the gravel, and got in with this friendly truck driver. Unfortunately, when we eventually made it to Minnesota and I got out, my suitcase in the back was gone. It had evidently fallen off somewhere along the way. So now the only clothes that I had in the world were on my back.

I made my way through Wisconsin, where there are a lot of fishing lodges and resorts. Then my luck changed for the better. I was picked up by some college professor and his wife headed west to see Yellowstone National Park. With my chauffeur license to prove I was a good driver and my smiling ways to convince them I was a good kid, I talked them into letting me be their driver. That way, I told them, they could enjoy the trip much more. They agreed, and so we headed west. We had a great time along the way. Once in a while we listened to the radio, and a few times we sang songs. Mostly though, we just talked a lot.

I took them up through several northwestern states, and they in turn bought me meals. We toured through Yellowstone. While the professor and his wife marveled at all the wonders of the park, I concentrated on keeping us on those narrow mountain roads and not falling down the sides and into the steep ravines. We rode around Yellowstone for about a week, and they were going to pay me to return home with them, but I had to keep going. So I reluctantly left them.

I then made my way over the northern end of Montana across a lot of dry, open areas. I hitchhiked during the day, and when sunset approached, I did what I had to finding myself a place to bed down. I had found out early in life that, to my surprise, if you stopped in a small town in the evening (and you did not make a nuisance of yourself), the local sheriff would let you bed down in their jail for the night. The cells were simple, usually with two cots. The deputy would almost always leave the jail cell unlocked, so that you could let yourself out in the morning and leave whenever you wanted to.

I kept going. Sometimes at night I slept in a haystack, or a bundle of shocked wheat. I hitchhiked northward on into Washington, and eventually made my way up to Seattle. I spent some time bumming around the docks just to learn a depressing fact: while it was true that the shipyards were hiring part-time, unfortunately, the type of job I wanted was not available. Odd jobs on luxury liners were non-existent. Everyone knew that war was coming to the U.S., and speculation was high that we would become involved in conflict with Japan at any time. The Japanese had been at war in China since 1933, and with our country now evoking a partial embargo on them, tensions were high. Therefore, the steamship companies, until further notice, were not conducting any luxury cruises in the Western Pacific. So the only job that I could get was to paint the ships.

Bull, I thought to myself. I ain’t gonna do that. How the hell can you meet a rich fancy broad doing that kind of a job? According to what I had read in the Hollywood magazines, the only way to connect with a rich broad was on a luxury cruise. And painting the hulls was sure not going to do that.

I finally left Seattle and hitchhiked south through California. I made it to the southern end of Modesto, and there I managed to buy some more clothes. Unfortunately, that took the last of my pathetic funds, so now I was flat broke. I got down to Hollywood and stayed for a while, still looking for one of those rich dames. Unknown to me, Alex had changed his mind and had come out to the Los Angeles area on a “bummin’ trip.” It was a big town even back then, and we never bumped into each other, but by funny coincidence, he and I each sent postcards home to our sister Elizabeth in Akron, who wondered why we were both in the same area and had not seen each other.

Towards the middle of summer, I decided that I had experienced enough adventure: I was ready to go home. I left Los Angeles and started hitchhiking eastward, across Arizona. Yuma was interesting. I remember seeing all these little shacks with slanted roofs, and in front of one was a Mexican snoozing with his sombrero over his face. That’s all I remember. Nobody out in the sun, nobody walking around. Just here and there a guy alone, sitting in front of his shack in the sun.

I kept going, northeastward across New Mexico, Texas, and then Arkansas. Although I always looked for opportunities, because I moved around alone, I was always on my guard. This was especially true after crossing the Mississippi River, because I remember as a kid being told that conditions in the depressed South were pretty bad, a lot worse than what we were going through in Ohio.

I remembered wild stories of guys going down there and just disappearing, or getting their cars sabotaged at restaurants or filling stations so that they needed to be repaired (and parts purchased) by some local yokel. You pulled into a gas station and when the attendant checked your oil, he would pull or cut a hose or a wire, and then tell you that your car needed to be fixed. I did not have a car, and so being on foot, I figured I would be even more vulnerable to somebody trying to somehow take advantage of me, being a stranger passing through.

Traveling through Mississippi, I sometimes came across a group of sweating guys working next to the road. Each man had an ankle bracket connected by chain to another guy, and they all wore simple uniforms of white and black horizontal stripes. With hoes, rakes, shovels, and bags, these gangs were working odd jobs along the roadside, like picking up trash, cutting grass, raking, pulling weeds, and making minor repairs to the roads. You know, back in those days, they did all that by hand. Overseeing the prisoners were these guards riding on horses, really nasty-looking fellows carrying these mean-looking double-barrel shotguns; definitely guys I did not want to even think about messing with. I was told that these groups along the road were the infamous Southern chain gangs that I had heard about.

This was my first experience with the South.

After that, whenever I could, I tried steering clear of these chain gangs, although sometimes I had to walk through one or two. I could see the convicts sometimes look over at me as they worked, and if I looked up at a guard, I would see him glaring back at me with cold eyes. I just smiled and kept on walking.

After a couple encounters like that, I became convinced that traveling down here for a happy-go-lucky guy was definitely not for me, and my wanting to get back to Ohio developed into a really strong drive. So I continued making my way northward, sometimes sleeping at night in the back seat of a car in a parking lot or better yet, in the trunk in a used car lot, because the dealers never locked the trunks. Otherwise, I would find me a nice tree to bed down under, or a nice haystack, or three-foot stalk of wheat.

I finally arrived home. Alex was already back. We sat that night and wondered what the next months would bring. I had been generally calm and lackadaisical about life up until now. Now war was about to break out. What would I do with my life now?

I was about to find out.

1 The Civilian Conservation Corps was a federal-government-sponsored program initiated in March 1933 by President Roosevelt. Considered a critical component of his New Deal, it helped offset the ravages of the Depression and to stimulate economic growth within the country. The CCC employed young males up to the age of 25 on various projects designed to improve the land. These included working on roads, forests, flood plains, dams, and various agricultural projects, especially if they had to do with soil erosion and land conservation. Workers were sent to all parts of the United States to work on such projects for construction, farms, working camps, rivers, and parks. Laborers were provided food and shelter, and given uniforms. The CCC existed until the Depression ended and World War II began.