Marine

By the summer of 1941, I decided that I needed a change in my life. I was still intrigued with the idea of joining the Marines, especially the parts about traveling and being able to see the world. I wanted to enlist, but I did not want to go in alone. I wanted someone to come in with me.

The idea of the Marines stayed with me. Alex, who was a year and nine months older than me, had received some sort of a draft notice at the end of 1940. While he did not have to report for military service immediately, it was a formal letter stating that it would only be a matter of time. He was just being officially notified. We suspected that he would be called up just after he turned 21, on July 25th. Still, it seemed plain that the government was giving him some time to make the appropriate preparations to his life.1

We both thought about his impending entrance into military service, now evidently no longer an option for him. His letter would probably come at the end of July or August, and mine probably would come some months after that. Alex’s choices were simple: the navy was out of the question, so he could join the Marines, or let the army induct him. Whenever I occasionally received a pamphlet from the Marines, I would show it to Alex, and he would read it. We talked about the Marines again in early August, and about the possibility of joining together, and I could tell that he was starting to lean in my direction.

One day, Alex finally said to me, “C’mon George, let’s go together. Let’s join.”

“Well hell,” I told him, “that’s what I’ve been trying to do!”

But Alex was not satisfied with just the two of us enlisting. He wanted us to go in with a bunch of our friends. So we decided to try and talk a couple of them into it.

“Let’s go see our buddies,” he told me, “and we can all go in together.”

I agreed. I felt so much better now that I had a plan. I mean, I had for some time decided that the Marine Corps could be my next big adventure, but I did not want to go in alone. I had worked in the CCC alone for two years, and this time I wanted someone to go in with me. Now I had Alex.

The military service would be good for both of us, and with luck we could share it all together. Besides, the military would give us something we were not used to: three square meals a day and a nice shelter to sleep in.

Boy, was I proven wrong.

The more Alex and I talked about joining the Marines, the more enthusiastic we became. We were, though, going to make an effort to get our buddies to go in with us; guys like Richard Tomkins and Waddy Getz, and John Siler, who at the time lived in the only other house near us, about a quarter mile away. Of the four of us, I was the youngest, although Richard was close to my age, but a year older. Waddy was as old as Alex, so his age was no problem. For years, the five of us had been close, sort of a gang within a gang. Alex and I knew that they thought the way we thought, that war was only a matter of time, and that we would all have to serve. So why not go at our choosing? Get in ahead of the rest? And of course, join the best service of the three?

Alex and I went out and talked to the other three about all going in together. We told them how advantageous it would be for them if they were already in the service when it broke out, and how we would do better as NCOs.

Sure enough, two of them, my childhood chum Waddy Getz, and Richard Tomkins, were eager to go in with us, and agreed to accompany us to the recruiter. However, John Siler did not like the idea. He was going to stay out of the service, at least as long as he could. After all, he had a halfway decent job and was making money for his family. John worked making insulators in the Akron Porcelain Factory, and felt that it was not quite time for him to enlist.2

Before the four of us left for induction in Cleveland, and with our Marine recruiter as an accomplice, we thought we would stry John once more. The Marine recruiter drove us in a government van to the factory on Cory Avenue to take a final shot at convincing John to join us. The recruiter gave us some last-minute advice, and then waited outside as we walked into the main building. We found John on an assembly line putting together insulators. He was working steadily, wearing a big white apron to keep the dust off. We tried to convince him to come with us, and our arguments must have been effective, because he waivered for a few moments before backing out. We nodded our heads in sad understanding, and one by one, we solemnly shook his hand, wished him the best, and bid him farewell. Talk about a corny guilt trip.

We left him, occasionally looking back sadly and walked outside, starting to head back to the van. Suddenly, the factory door slammed open and John hurriedly came out.

“Wait, you guys!” he shouted.

We stopped. He walked up to us, untied his apron, grabbed it, threw it off, and slung it over a rail.

“The hell with it,” he told us, “I’m in!”

We laughed and slapped him on the back. Happily, we all piled into the van, one big gang, and the recruiter pulled out of the parking lot to take us to the induction station in Cleveland. It was a happy trip and we joked all the way up, laughing about what we would do as Marines.

On August 5, 1941, just seven weeks before my 19th birthday, and as it turned out, four months and two days before Pearl Harbor, all five of us were sworn in to active duty in the United States Marine Corps.

I was still seeing Phyllis off and on, but at times I was more going through the motions than actually courting her. We were though, close friends, and could tell each other just about anything. Still, I guess in the end, it was a relationship of convenience for both of us.

Well, it was for me, because I had too much of a roving eye. For instance, the week before I left for boot camp near the end of July, I met another pretty young lady. We went out a few times over a couple weeks, and I guess that she fell for me in the worst way: this little gal wanted me to marry her. She tried her best to talk me into it and sweet-talked me silly for two days straight. However, I was definitely not ready to settle down. I mean, she was a great little gal to spend the evening with, but I was certainly in no mood to get married, especially since I was going into the Marine Corps, so I let it go at that. However, before I left her for the last time, I gave her a picture of me.

Unfortunately, that backfired on me, because a few weeks after Alex I had left for boot camp, this girl and Phyllis bumped into each other one night, just outside of Barberton. There was this huge old building that was a dance hall that served alcohol, and mercifully, they were not particular to whom they sold their beverages. This hall would often have dances, and big ones on Saturday nights. There were many like this in those days, and invariably, they were usually located way out in the country. I would often go to this one with my buddies and have a great time.

This one night then, they happened to accidently meet and began talking to each other. I guess they liked each other right off, and soon they were sharing their lives.

Finally, the subject of beaus came up. One of them must have said to the other, “Well, my boyfriend’s in the Marine Corps,” and the other one probably had replied, “Well, so is mine.” At that point, they each pulled out a photograph of their boyfriend, and of course, they both turned out to be of the same guy—yours truly. Phyllis got a big kick out of it, but the other gal (I cannot to this day remember her name) definitely did not. When I returned from the war, she would not even speak to me. Many years later, I tried to find her just to talk to her, but I never found her. She had moved, and I never heard from her again.

Boot camp

A couple hours after the swearing-in ceremony, we were all sent to Parris Island by bus. We were about to go through a grueling set of weeks together in boot camp. As soon as we got off the bus though, the first thing that they did was to split all five of us up. Funny, but after boot camp, I would never see John Siler again. So much for joining with my friends. Right after that, they gave us haircuts. The barbers were ruthless, and when they were done, you had less than a half inch of hair on your head (I was later told that it could have been worse. In the brig, they cut all of your hair off.) The effect was devastating on a lot of these recruits. Many of them had these real fancy hairdos that they often combed and greased down with hairstyling stuff like Brylcreem. So all that hair getting cut off really did a number on their heads—in more ways than one. It was like destroying their personalities, which of course, is what the Corps did.

Then we went over to the supply building; gruffly tossing stuff to us as we went down a line, they issued us our gear, complete with a sea bag and a helmet. It was one of those prewar salad bowl-looking helmets. We called it the “Frank Buck” helmet, because it looked like one of those old ivory pith helmets that we used to see him wear in magazines when he went hunting on a safari in Africa.3

With our gear issued, they assigned us barracks. Most of the barracks were these cheap, wooden buildings, which is what I landed in. We each had a cot and a big footlocker for our gear. As soon as we had our gear stowed away, they told us where the pails, soap, towels, and scrub brushes were located. Then they ordered us to start thoroughly scrubbing our wooden walls down. It was a thankless, gloomy job, and those of us that had become upset by the haircut experience were now joined by most of the other kids. Many were really out-and-out scared, and a couple of them said, “Oh my God, what the hell did we get into?”

They stayed agitated like that as we were scrubbing, but unlike the others, I found the whole thing amusing. They had been so enthusiastic coming down here on the train, laughing and shooting the bull, and gaily singing the Marine Corps Hymn. Now they were mumbling to each other, scared to death about what was happening to them as reality set in, and they began to realize that these boot camp instructors were like monsters. The more I looked at them, nervously scrubbing, the more it seemed funny to me. So many of them had really serious looks on their faces. One guy actually had a couple tears in his eyes. Looking things over, I thought that maybe a little levity here might go a long way. So with a chuckle, I grinned at them, opened my big mouth, and started singing, “From the halls of Monte-zuuu—uu-ma, to the shores of Trip-pooo-liii …”

Again, another one of those times where my sense of humor did not work, because the other recruits glared at me and started shouting stuff like, “Shut the hell up, man!” and “You sonuvabitch!”

Obviously, I was a different breed of cat.

I continued laughing and singing for a bit, enraging the other guys, but I did not keep it up for too long. Mostly, I quit because I knew that if the D.I. caught me singing like that, he probably would have thrown my butt in the brig.

I had luckily got some critically important advice before joining the Marines. I was told to never volunteer, and to never disclose to our “G.I. D.I. from P.I.”4 the many types of training and certifications that I had received in civilian life. The various types of training that I had earned in the CCC, my chauffer’s license, my qualifications and certification with explosives—all were to be kept secret. The reasoning was simple. The main purpose of boot camp, I had been told, was to break the individual down in every way: physically, in spirit, in habit, and in mental attitude. It was from this lump of a man that they wanted to mold their no-questions-asked fighting warrior.

As it turned, out, that advice was sound. Those few who did disclose previous training in various types of machinery or operations were ridden especially hard, and given much more extra work to do, or details to go on. It was almost as if they resented the fact that you had some outside experience, because you had not been taught to do what you did their way. To them, the recruit was not supposed to have any ideas of his own. That would maximize our efforts to fight in the most efficient way possible as a team, because that is what they were going to teach us. They had to break you down so that they could teach you their way. There was no room in the Marine Corps for preset ideas.

There was one guy in our recruiting class that had been in college. While he was not totally out of shape, he was a somewhat heavyset fellow. When he proudly (even a bit cocky about it) admitted to the drill instructor, the D.I., that he had been in ROTC, it was like he was suddenly marked. The D.I. after that rode him mercilessly. In everything we did, if one of us screwed up, we all paid the price. With this guy though, the D.I.s always checked to see if he had screwed up, and if he had, they would go out of their way to showcase him and make him pay.

In the end, he did not make it through boot camp. One day on the obstacle course, he fell and injured his leg. The medics hauled him off in pain, and he ended up with a broken leg. So they pulled him.

It was only after boot camp that we learned the drill instructors wanted to tear down any preconceived notions and experiences that we had acquired in life, so that they could rebuild us their way. That was one of the reasons for the haircuts. So to know what they were up against, they would try to trap us into admitting our past experiences, so that they knew whom to concentrate on.

For instance, they would ask, “Hey, are there any truck drivers here?” And sure enough, a couple guys would answer with a smile, thinking that they would get slated for special training.

Wrong.

“Okay,” the sergeant would growl. “There are some wheelbarrows over there. Grab one and follow me over to the latrine.”

Luckily, I already knew their strategy, so I very quickly learned not to freely give them any personal information, especially work experiences, and not to volunteer for special details, or unknown duty requests.

The D.I.s were brutal in their schedules and excessively harsh in their training. And they had absolutely no pity for us in their instructions. Me, I survived because I quickly developed an attitude, probably coming to a large degree from my experiences on my own. Suffering the pain and misery of boot camp with my fellow recruits, I had early on gritted my teeth and swore under my breath that these sons of bitches would never ever break me. I would not yield, I would not give in, and I would never give up. No matter how harsh the exertions were, I knew that I would either make it to the end or die trying. So I never fell out of a formation no matter how exhausted I was. Nor did I ever miss a day because I was too bone-weary to get up. I would be there standing when it was over, no matter how strong-willed the D.I.s were. It was me against them.

But man, did they make it hard for us, especially the first few weeks. I was told months later that one reason for this was to introduce the idea of inducing pressure and stress, so that we would have less tendency to freak out when we went into combat. Still, even if we had known that back then, it would not have made things easier.

In our platoon was this Jewish fellow, a guy about five or six years older than most of us. Probably because of that and because of his faith (there were a lot of prejudiced guys in the Corps back then), they really rode him hard. Somehow he persevered and managed to make it through each day with the rest of us.

One morning we were marched over to the medics’ tent to get shots. And we found out that we were going to get a bunch of them. This was no fun, because they did not have those high-pressure jet injectors in those days to give you multiple vaccines at one time. No sir. They gave the shots to you the old fashioned way: one at a time. So with our T-shirts off, we would slowly walk through the main corridor of this large tent, with a row of corpsmen standing on each side. You walked down the aisle, pausing at each station while the corpsman on each side of you would jab a needle in your arm and give you the shot.

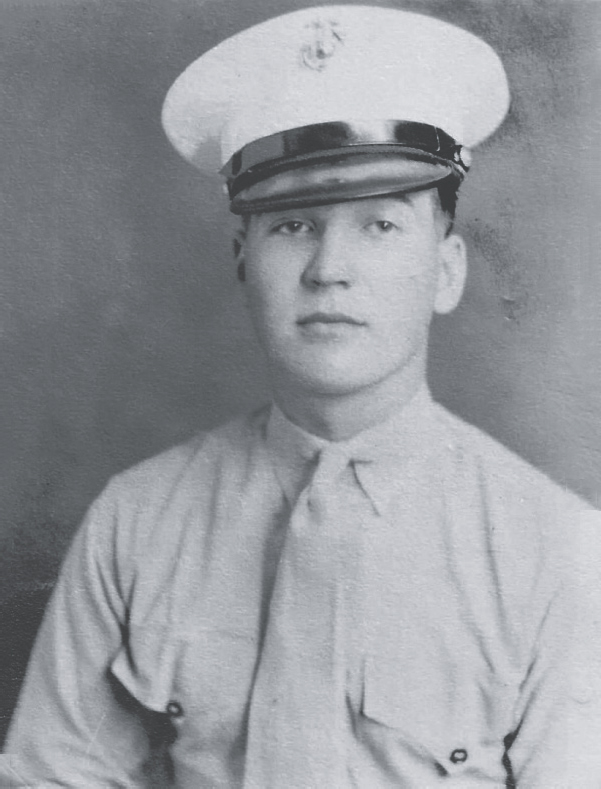

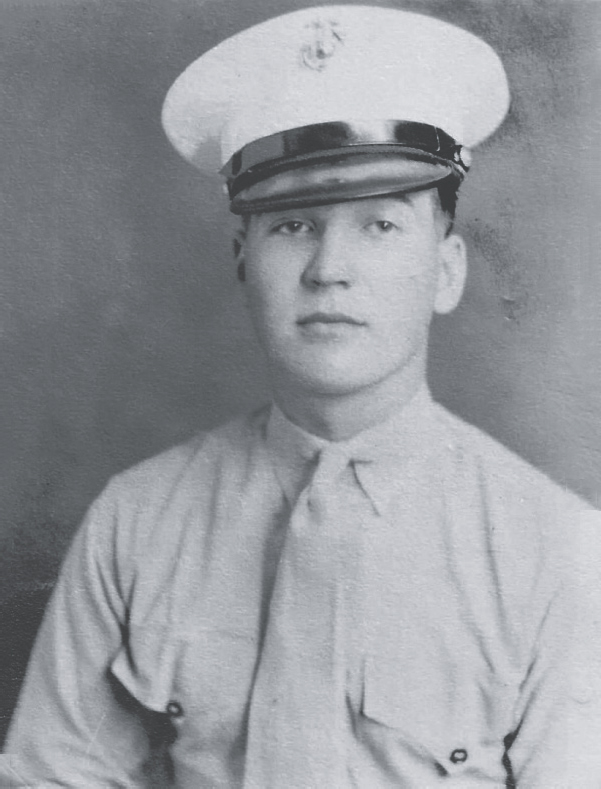

George when he was at boot camp, fall 1941. (Author’s collection)

It was not surprising that after that session, when we left the medical tent, our upper arms were sore and our heads a little groggy. We walked out into the hot sun, and lining us up in formation, the D.I.s began to march us back to our tents. Unfortunately, the gunny in charge was one of the more sadistic bastards, and looking at us, he growled, “Oh, don’t feel good, eh?? Well, I will not stop until each of you SOBs drops. If you babies are sick, go to sickbay. Otherwise, you march!”

And we did. We marched all over the place, and drilled for a hell of a long time out there in that intense South Carolina sun on that damn hot August day. Soon, some of the recruits began to drop, too weary to move, and that D.I. would bitch at every one of them, sometimes giving them a swift kick.

Finally the older Jewish recruit in our group who had been slowing down in the paces groaned and collapsed. He dropped to the ground, falling on his back. The sergeant walked over to the recruit, and towering over him, he yelled, and then viciously slapped the hell out of him. The Jewish guy did not move.

Looking down at him, that husky sergeant paused and growled, “Well, I guess he ain’t fakin’ it.”

We went on marching and left that poor guy lying there. A couple of corpsmen finally hauled the unconscious recruit off, I assume to sickbay (although I never knew if he made it there).

More of the guys began to fall out of formation and tried to stagger off to sickbay. As tired as I was though, I resolved not to drop out. Huffing and puffing, I gritted my teeth. No sir, I thought, them bastards ain’t gonna break me. At that point, as far as I was concerned, it was me against the world, and I was going to march until those sons of bitches killed me. I kept on, somehow finding the energy to keep going. My legs ached and my body was in pain, but I grimly kept going.

Finally, the gunnery sergeant, really steaming because we had not all dropped out (less than half of us out of the original twenty), determined that was enough, and marched us back to our tents.

A day or so later, we were told that the Jewish fellow had left the unit and had been transferred to the “Casual Battalion.”5 The rest of us, now all trained and qualified as a rifleman, began to split up into different specialty fields. I wanted to be on the mortars, hopefully as a fire observer. Unfortunately, there was no school for mortar observers, so that was the end of that.

After weeks of what seemed like a terrible ordeal dished out by cold, ruthless D.I.s, boot camp came to an end. There was no ceremony or celebration—back then, you didn’t “graduate” from basic training. You just completed boot camp and got reassigned. It was like getting out of jail: no big deal. When you were through, they just shook your hand, told you that you were now a Marine, and then gave you a new assignment.

Alex was given his orders: 7th Marine Regiment, First Marine Division. He was to report down to New River.6 He immediately had to pack and after a handshake, he left for training there, to then go with the division to the Pacific.

Waddy Getz was sent to Balboa, in Panama. I never found out where my old chum John Siler went. Richard Tomkins was ordered to the field music school, located right there at Parris Island. It was not much of a music school though: all they taught those Marines to play were bugles. Richard begged me to volunteer to go too, and it seemed like a great way to serve in the Marines. Unfortunately though, I had never had any use for music. I had a lousy singing voice, and I didn’t know how to play any kind of musical instrument. My music experience in school had been terrible, to say the least. So bugles for me now were out of the question. The hell with field music school, I told Richard. He was disappointed, but I didn’t care. I’d shovel crap first before I tried to play any instrument.

As the rest of those in my platoon got assignments, I remained. The only one who stayed was Tompkins, who assisted me on the rifle range. Life was a drag. You couldn’t just walk around the base. We were not under any circumstances allowed to go to the PX and buy some “pogey bait” or “belly wash.”7

Instead of going west though, along with several other recruits, I was transferred to some rearguard company, and in late September 1941, we were ordered to New England for guard duty. The next morning, carrying our gear and rifles, we boarded a train and started rolling northeastward. Our thousand-miles-away destination: Quonset Point, Rhode Island.

Our train went up the Atlantic Coast and then over towards New York City, where we were going to have a layover. We got off the train at the Central Railroad Terminal in New Jersey and crossed the Hudson River by ferry into New York. We then marched right up Fifth Avenue to Grand Central Station, where we were to stay for the night. Off the main area of the station, we piled our duffle bags, stacked our rifles, and then we posted a couple guards. The rest of us then had the opportunity to spend the evening looking over the city, although none of us strayed too far away.

We reboarded the train and went up to Quonset Point, Rhode Island, where we reported aboard. We found the accommodation nice. The buildings were all connected, including the mess hall, the brig, the supply room, everything. It was a wonderful new building, and you did not have to go out into the cold to go to chow. After Parris Island, it was like being on a vacation.

There was of course back then, no public address system, so all of the daily tasks on each base were ruled by the bugle. Our bugler had this knack of being able to stand in a certain spot in the central building, and when he blew the call, the sound would bounce back and forth across the walls and echo down all the hallways throughout the complex. So you could clearly hear him for reveille, raising the colors, chow, assembly, taps …

Just after I arrived at Quonset Point, I was ordered on a 30-day tour of duty to Hope Island, right in the middle of Narragansett Bay.8 There I was given the assignment of guarding bombs in storage for the new naval air station that was being expanded back at Quonset Point. Unlike the nice, all-connected brick barracks that we had enjoyed though, those on Hope Island were plain, small, plywood shacks that had room for only eight people.

Hope Island was only accessible by ferry. Since all during that time none of us on the island was allowed to go on liberty, and the weather was getting worse, our off-hours options were quite limited. Mostly we sat around the barracks, and with not much to do, we had plenty of time to shoot the bull and get acquainted. Still, it was a long, long 30 days, especially if you had a girlfriend in town, like some of the guys did.

Around this time, I made friends with a fellow Marine, a guy that I would serve with for some three years. His name was Henry Vastine Rucker. We had both entered the service about the same time, only in different parts of the country. I was a Yankee from Akron Ohio, and Henry was a rebel from some town called Gaffney in South Carolina. We were both 19, and were both fresh out of Parris Island. From just about the first day that we met, we took a liking to each other.

Like I had figured it would be, guarding bombs on a small island in the middle of nowhere was a mundane job, and for the adventure-loving kids like Henry and me and a few of the others, it was positively mind-numbing. Not all of us there though were kids. One time we came off of duty there and found this old guy taking a shower. Assigned to our unit, he had been swimming around in the ocean and was now washing off the seawater. As he walked out of the shower I got a good look at him. Man, did he look old. He introduced himself to us. He was a World War I veteran. The proper term we used was “retreads.” They had evidently taken him back into service. Now they had called him back to do guard duty so that the young guys like us could get shipped out.

There were only two exciting things that happened during my time there on Hope Island. The first one was after we had been there for a week or so. One of the guards came into our barracks one day, having stood guard duty. He took off his heavy coat and sat down onto his lower bunk. The guy above him was cleaning his weapon. Unlike most of us, this guy had one of the new M1 rifles. Most of us had those old .03 Springfields.9 Anyway, the guy above, in the process of cleaning his weapon, banged the edge of the stock against the wall. Evidently he must have forgotten that he still had a round in the chamber, and when he smacked it the rifle accidently went off. The bullet zipped down and hit the guy below in the end of his butt. We all had a good laugh over that one, even the guy who had been shot.

The second exciting thing happened a week later. One night, one of our sentries called in to report that he was pretty sure that he had seen, of all things, a submarine. He supposedly had spotted it in this little bay on the far end of the island. That caused a stir, because if the Germans were to land a raiding party on the island, we would be in big trouble. There were only 30 of us on the island, and all we had to defend ourselves (and those damn bombs) was our rifles, most of them those trusty old Springfields. It was quickly decided that we would have to get the drop on them. So on that cold windy night, all of us Marines prepared to lay siege to a German U-boat.

Armed with our rifles and wearing our Frank Buck helmets, heavy coats and gloves, we moved in silently around the suspected cove. As we quietly approached, a couple guys said that they thought they could actually faintly hear chains clanging and other noises they could not identify.

Moving up in the pitch dark, it was impossible to see anything. So the officer in charge told us that we were going to wait for daylight to come. Then at the crack of dawn, we would rush the sub, board her, and take her by force, either capturing or killing its crew members. We crouched there in the night for a few hours, chilled as the wind blew. Once or twice again, a guy ahead of us swore that he could hear chains rattling way off in the distance. Henry and I were as excited as a couple of schoolboys, and we whispered comments about the whole thing to each other in the darkness. Hey, if we captured a Nazi sub, we would be big heroes and probably each get a medal. We grinned at the idea. That would really be something to tell our folks back home.

The early morning hours seemed to drag on and on, and finally the sky began to get lighter. The noises coming from the direction of the sub had long stopped, and we now waited, getting ready to pounce. Daylight broke over the cove, but a heavy fog kept us from seeing anything as we lay shivering in the cold behind boulders, our rifles pointed toward the enemy. Slowly the fog began to lift as the sun rose. The officer gave the word, and we started moving in on the cove. Coming up to it, we were surprised to find it empty. Nothing. No sub, no Krauts … nothing but an empty cove.

Needless to say, there were 30 damned embarrassed Marines who returned to their barracks on Hope Island that day.

After our 30 days guard duty assignment was finally over, Henry and I were returned to the Quonset Point Naval Base on the mainland and we were allowed to go on liberty in Providence. Naturally, Henry and I tried to catch up on lost opportunities, so we over-indulged, and the next day, my head felt like it was going to fall off.

Later in October, my brother Alex got leave and hitchhiked up the coast to see me up in New England. Although he was not authorized to, he stayed at our barracks for a few days and slept in a vacant bunk, Alex wore on his uniform the French gears braid.10 When we went out on liberty, a couple people noticed the braid and asked him if he was Canadian, which, of course, he got a kick out of (I have it to this day, although I still cannot figure out how I ended up with it). After a few days, Alex left to return to the First Marine Division, training at New River in North Carolina. I did not know it when we parted, but I would not see him again until after the war.

More guard duty assignments came, and I stood guard through Thanksgiving. It was during that time at Quonset Point that I occasionally came in contact with a certain 29-year-old lieutenant JG,11 a fellow that would someday become president of the United States—of course, who could know back then?—Richard M. Nixon. He was always a serious-looking guy, and to me always seemed to have a sour look on his face.

From our barracks, the view was beautiful. I could walk 200 yards and look out over the Narragansett Bay. On all but snowy days, you could look out and see islands on the other side,12 some of them two miles away. Many was the time I would gaze out into the slot in between and watch an occasional destroyer go by, because there were a lot based there.

Some of us were good on liberty, and some just plain were not. For instance, there was one big tall guy in our group named McNolan or McNorris, or something like that. We just called him “Filthy McNasty,” mostly because he had a foul mouth and a rotten disposition on life. Since he was a big mean guy, he would often go looking for trouble, which, when I was hunting gals, was the last thing on my mind.

One day, a few of us were on liberty in Providence. We had been bar-hopping when we went into this one place for a few more drinks. It was called the Five Points Bar, because it was located at the intersection of these five streets in the southern part of town. The gal that owned the hotel above the bar was in her seventies, but her daughter Charlene was only 32, and I must say, she was not bad looking for her age. So even though she was an older woman, I had started dating her. Okay, I was 13 years younger than she was, but what the hell, when it came to women I didn’t play favorites with regards to age. And anyway, as long as I dated her, her mom took care of our room when we stayed there.

The Five Points Bar was a big place, with a long L-shaped bar on the right side. Next to it were the tables, with dozens of sailors sitting and standing around, all of them drinking. Hell, there must have been over seventy of them. On our guard, getting a number of dirty looks, we sat down in the back and ordered some drinks. I was there to have a good time, and did not want any trouble. McNasty though, being the foul guy that he was, evidently did, because he began to badmouth the sailors, bragging that he could whip any bunch of them.

Ho boy, I thought. Here we go.

One of them finally told McNasty he had better shut his damn mouth up, which of course, just egged him on further. He looked at them with a mean grin and said, “Screw you. I can lick all of you swabbies.”

They looked at each other and sure enough, a bunch of them got up and decided to take him up on his offer. We all went outside, the sailors crowded around us, and some of them lined up to fight. After a few moments, one or two started towards him. McNasty growled and lit into the first guy, and then the second and third. Sure as hell, he took out about five of them pretty good. He was holding his own okay, but daggone, there were dozens of the bastards waiting to get their shot. Besides, he was starting to get tired and they were coming at him fresh.

Naturally, the fight expanded, and soon all of us Marines were in it. We finally took refuge by going inside the bar again, and moved to the back. You know, it’s always nice to have a wall behind you, just in case you have to defend yourself. And with all these sailors coming at us, that was a good thing. Besides, we could hightail it out the back door if we needed to.

As the swabbies started towards us, we realized that while we had no worry about getting hit from all sides, we were essentially trapped. A minute later though, the police burst through the front door with their billy clubs, and man, I was never so happy in my life to see them. They broke up the fight, rescued us, and luckily turned us loose and allowed us to go on our way. But McNasty, beat up and bloody by then, was taken to the hospital. I have to admit though, he was fighting like a demon right up to when the MPs broke things up.

You would have thought that I would have learned to stay out of trouble after that, but it just seemed like trouble followed me wherever I went. A few weeks later, we were on liberty again. On this night, four of us ended up at a place northwest of the Five Points called the Homestead Café. Again, we had a table sitting in the back of the bar. I guess we hadn’t learned our lesson at the Five Points, because although no one could attack us from behind, if trouble were to start, we would be blocked from getting out.

We had been there for a couple hours drinking, and I guess you could say that we were having a good time and in a pretty relaxed mood. One of us though, was further gone than the rest of us. In fact, he was pretty boozed up and had reached a point where good judgment had left him. At that point, he got up, staggered over to one of the booths along the wall, and began talking right to this woman sitting there. We knew there would be trouble and looked at each other, because the lady was obviously married and sitting next to her husband. And there was our buddy, openly putting the make on her, with her husband getting ticked off.

Well, this did not last very long, and after a couple minutes, the husband had had enough and told our drunk buddy to take a hike. He responded by exploding into a rage. He yelled that he was going to whip the crap out of the husband and beat his ass and this and that. Hearing his outburst, a lot of folks in there became angry and took sides with the husband.

It was then that I realized how much this was some kind of a local neighborhood bar, and that these folks were all regulars who all knew each other pretty good. So there we were, sitting in the back, with all these guys in the place now mad at us and standing up to defend this local guy and his wife. The three of us sitting down definitely did not want any trouble. The problem of course was to figure out how the hell we were going to get out of there without getting our damn necks broken. I mean, there were guys standing near the front door with clubs and looked like they really meant business. And again there was no back door escape. We were cornered again.

Okay we decided, it was time for us to make our move. So acting on what we had learned in the last few months, we each took off our webbed belt, made a fist, and wrapped the belt around it, with just six inches and the belt buckle at the end of it. We stood up and staring around, we slowly began to walk through that mob, this wedge of three guys. They glared at us, but they grudgingly parted for us as we walked towards the front. We grabbed our drunk buddy, apologized to the guy and his wife, and walked away as we told folks that we did not want any trouble. We reached the door and got the hell out of there. We just walked off quietly. Afterwards, we had to restrain ourselves from killing that S.O.B. for getting us into that mess. He was nuts. Just as much as McNasty.

War

At the beginning of December 1941, I was given an assignment to stand guard next to a large vehicle storage complex around Davisville, five miles west of the base.13 In it were several acres of machinery-type trucks and construction equipment. I had the 0400 to 0800 watch, which was a miserable time to be guarding a bunch of trucks. I’d stand watch for four hours, get eight hours off, and then be on again and so on for three more shifts. I stood guard next to a small wooden shanty that bordered some woods. At that time of day, very few workers came into the complex. I was bored, to say the least.

About an hour into my watch on December 8th, as I stood there in the freezing cold in my dingy little hut, shivering in my winter coat, feeling miserable, trying to see, one little light bulb as my only source of light, a jeep came barreling down the road and around the corner. I saw some lieutenant driving. The jeep skidded to a stop, and I stared at him.

He looked at me and said, “Japan attacked Pearl Harbor.”

Without another word, he took off again, roaring down the road, leaving me in dark silence. I stood there in the dark, stunned, speechless, wondering, trying to figure out what the hell had just happened. Japan? We were attacked? Was this the start of the war that everyone had been predicting? I looked down at my Springfield rifle. I had just ten rounds of ammo and no extra clips. What in blazes was my 19-year-old butt going to be able to do if I was attacked?

As the wind softly rustled through the trees, I looked out at the cold, silent, dark woods in front of me. My imagination went to work, as I began to worry. I could almost see dark, skulking figures moving around way back in the trees. What the hell could I do if a bunch of Japs came out of those woods? I wouldn’t stand a chance. I stood there, alert, worried, and still cold.

That was my introduction to World War II.

A few hours later that morning, after I was relieved, instead of going to get some rest, I was taken over to the main gate of a nearby work facility to do more guard duty. Along with a couple other Marines, I was ordered to guard some twenty of those semi-round Quonset huts. Each one had a mini-factory or work assembly section inside, in which a dozen or so civilians worked every day.

Although we technically were not at war (word of the declaration of war would not come until that afternoon), because of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, new precautionary actions were initiated. When the workers came in to go to work, we now had to frisk them. We were told to be really thorough, too; insides of hats, pockets, cuffs, wallets, and shoes. We had to even check the workers’ thermos jugs and make sure that they actually contained liquid. Needless to say, these guys were infuriated at this new set of security measures. It really upset them that even though they were good, staunch, patriotic Americans, they were all of a sudden no longer trusted by their own damn government, and personally, I agreed with them. So I resented doing what I was ordered to do, and I hated to humiliate them by checking their personal stuff. I did not for a moment want to hassle those folks.

After the work shift began, we were then told to go into the facility and patrol around. Smoking, which was a habit quite common and even encouraged in order to “be cool” in those days, was now forbidden. No cigarettes, cigars, or pipes, and we had to strictly enforce the rule. Again, there was more resentment from the workers, and we guards took the reaction of their discontent and although they did not blame us, they took out their frustrated emotions on us. This became a daily routine, and the whole thing quickly became for me a real crummy job. I decided right there that I would never want to be a cop, and that I had to find a better use of my talents.

In January 1942, the facility was given a formal dedication ceremony, and I was in the Marine honor guard for that event. And to make me feel better, on the 23rd, I was promoted to private first class.

In the months that followed, I did various types of guard duty here and there. On the plus side, I did get to go on liberty a lot, and several of us would go together. There was me, Henry Rucker, Emanuel James “Jim” Olivera, and a fine Marine named Jefferson Davis “Jeff” Watson, Jr. from Jacksonville, Florida. Quite often though, we would hit it off with the girls and go our separate routes. There was one gal in Providence that I dated for a short while. Her mother owned this hotel above Five Points. She was nice. Then there was this barmaid I knew at a rathskellar14 in Fall River, Massachusetts. I liked her a lot, too. Still, I guess I was not the marrying type in those days.

One day that February, I was given the assignment of guarding a load of ammunition on a train. I was told that I had to sit on top of this boxcar with my .03 Springfield. I was told everywhere that train went, I had to go too as guard.

The day we loaded up in the railroad yard in Davisville was a cold one. My assigned boxcar was located about three or four cars back from the engine, and as the train started southward, I sat up there on the edge of that boxcar with the wind whipping at my face, hunkered down, shivering, freezing my butt off, and generally feeling miserable.

Finally, we made a stop and the train engineer walked back and looked up at me. “Hey, it’s cold as hell,” he said. “There’s no need for you to stay up there freezing, Marine. Why don’t you come on down here and get in the cab and get warm?”

Well, he sure as hell didn’t need to ask me twice, and I told him gratefully, “That sounds good to me.” So I climbed down off the boxcar and walked over to the engine. Wow. What a beautiful piece of machinery I thought as I climbed into the cab.

There were two guys: the old engineer and the younger fireman, who was fueling the engine. He would open the steel door at the bottom of the furnace and shovel in some coal from the coal car behind us. Then he would clang the door shut, and then turn around for another load. In front of the engineer was this large black iron bar that ran diagonally in front of his spot. He took a hold of it and looked over at me. Curious, I stared at him.

“This is the throttle,” he told me proudly. “You use it if you wanna drive.”

“Uh huh,” I said, my mouth open. Wow.

He grabbed a cord and yanked on it. The train whistle blew with a roaring whoo-whoooo! I laughed when I heard it. Then he grabbed the throttle and pulled down on it, and I heard steam rush in somewhere inside the engine. Very slowly, the train began to move. I marveled as we gradually began to pick up speed. I intently looked over the pipes, little wheels, and dials in front of us as the engineer explained what they did.

I volunteered to help shovel the coal, and the fireman grinned at me as he handed me the shovel and showed me how to do it. I grasped the shovel with my Marine gloves and eagerly stood there.

He looked at me and said, “Okay, just get a good scoop of coal from behind ya there, and then turn around, step on that lever right there, and just shoot the coal in. Then ya just take yer foot off the lever, and the door’ll close. It’s that simple.”

I grinned and nodded. I turned around, heaved my shovel into the coal behind us and got a good load. I turned again, walked over to the engine, and like he showed me, I stepped on that lever on the steel floor to open the door. When it clanged open, I shoved my load into the orange hot fire inside. Then I yanked the shovel back and let go the lever. The door clanged shut. I grinned at him again and turned for another load. Another shovel full, opened the door, tossed the coal in, let off the lever, the door clanked shut. Daggone, this was fun! It definitely beat the hell out of sitting on top of that damn boxcar, freezing my butt off. So I shoveled coal for about five minutes until the fire was good and hot. Then the engineer asked me if I wanted to drive.

I was stunned. Wow. My eyes wide and my mouth open, all I could do was nod. Me, driving that whole damn train. I had jumped a lot of them as a kid. Now I had the chance to run one!

He reached out to the iron bar. “This is the throttle,” the engineer told me proudly, his glove on the end of it. “You use it to drive the train.”

“Yeah?” I said, mesmerized.

The engineer grabbed the large diagonal iron bar on the left side that ran diagonally in front of his spot. “Like I said, this is the throttle. You use it if you wanna drive. You just take that bar and pull her down.”

Pull it down. Okay. Hesitantly, I grabbed the big iron lever and looking at him, the back of the engine, and then at the lever, I began to pull down on it.

The train seemed to jump forward as the wheels started to spin faster.

“Whoa, take it easy!” he laughed. “Easy.”

I let off the bar a bit, and the wheels grabbed onto the track and the train began to speed up.

Holy crap! This was great!

After about fifteen minutes of pure ecstasy, he took over control again. We ended up dropping our loads off in some small town, and then through a series of switches and side tracks, we turned around and made the return trip. Since there was no ammo on the train now, I figured that I did not have to sit up on top of that freezing boxcar. Besides, I damn sure liked riding with the engineer and fireman, and they welcomed my company.

At the end of the trip, the truck that came to pick me up had trouble finding me, because the train was in a different position than before, and I of course had to stay with the train. But I had a blast doing that.

Winter turned into spring, and when summer came, I briefly served guard duty in Newport. Then I returned to Quonset Point, where I stood guard over various vessels that came into port. For those assignments, I had to stand watch on this long flat dock adjacent to the land. It was boring, and I remember those winter days being icy and cold as hell. Chilly winds came in right off the ocean, and I would have to stand watch out there, sometimes in snow.

I did more months of boring guard duty at government facilities, next to trains, submarines, and various ships along the East Coast. One of those vessels in the early spring of 1942 was this huge aircraft carrier, I think the USS Hornet.15 I stood guard next to the gangplank walking back and forth in the dirt for one night. It was pretty cold and dark, and even wearing that heavy wool overcoat that hardly let me move, I was still chilled.

I found life there at Quonset Point interesting. The commander of our Marine guard detachment was a Major G. H. Morse Jr., a really serious type of guy. In our spare time, he made damn sure that we drilled over and over. We marched every day and did the order arms until our arms ached. We practiced all sorts of rifle exercises, and we got really good. We could do all kinds of fancy stuff, including drills like the Queen Anne’s Salute. We went through different marching formations until we got good, and then went on and on until we were excellent at marching and turning in blocks.

When we were not outside drilling or on guard, we worked on our .03 Springfields. I learned to wipe linseed oil over the stock and then slowly rub it into the wood. Repeated treatments customized the wood and built up coats on the surface, and as they did, the wood would really shine. Yeah, we polished those butts to the point where they were dazzling, almost like glass.

And oh, our uniforms. Anywhere we went, we had to be all spit and polish, and so we spent endless amounts of hours cleaning our blouses, pressing our guard pants, working on our covers, shining all our brass, spit-polishing our shoes, and of course, cleaning and shining our rifles over and over again.

The summer went by, and we continued our guard assignments. To make sure we kept looking good, every Saturday, Major Morse and his executive officer would line our two rows up on the parade ground next to the barracks, and he would meticulously inspect us.

I remember one particular Saturday morning. Henry and I had been doing some serious drinking the night before, and now I was hung over, and my head was splitting. Still, I dressed with the rest of the guys and walked out to the parade ground, my stomach churning and my head swimming. We assembled in formation as we always did, and when Major Morse called attention, we snapped to. We stood there as he began his inspection, starting with the first row. As he slowly walked down the line, I struggled to stand there, my stomach growling. Oh please, I thought, let’s get this stupid thing over with before I puke.

Morse finished going down the first row, turned, and began inspecting ours. I clenched my teeth as my head began to swim and I started to get queasy. He slowly continued down our line, finally passed me, and turned to do the last row. Finally, after what seemed like an eternity, he finished his inspection. He walked back to the front and ordered us to parade rest.

He then began some speech. He was saying something, but I could not make out what he was saying, mostly because I was hurting, struggling at this point just to stand there. My stomach was getting worse, my head was killing me, and I could tell that I wasn’t going to stay long the way I was without letting go of whatever was in my stomach. I was getting desperate, and his talk did not seem like it was going to end any time soon. The time crawled, and I realized that I had to do something. But I just couldn’t raise my hand and tell the major I was sick. He’d yell at me and probably throw my butt in the brig.

Things inside me were coming to a head, though. I knew that I was about to let go, and I could tell that this one was going to be a big one. Yet I just couldn’t hurl chunks of food and old booze on the clean backs of the guys in front of me. Nor could I turn around and do that to the guys behind me. I was stuck in this damn formation. Still, I had to do something as the nausea increased. I realized that it was about to happen, and there was just nothing I could do to stop that.

Well, if that was the case, I thought, since we were a guard unit and were supposed to do everything smartly, I decided that if I had to get sick, I was going to do it and go down with some snappy style. I was going to let fly, but by God, I was going to do it in a military manner. Taking a couple deep breaths, I impulsively snapped to attention and presented arms. I then did a right shoulder arms, took a sharp step forward, did a right face, and began briskly marching between the rows. I was barely aware that the major had stopped talking, and no one else said or even mumbled anything as I marched. I knew though, that all eyes were on me.

Oh Lord, it was getting ready to come up as my stomach rumbled like a volcano about to let go. I smartly marched over to the end of the formation and made it a couple quick steps beyond. That was about as far as I got. I stopped as the stuff came up and my mouth began to let loose. I had to admit, struggling as I was, the force and distance of what flew out impressed me as I stood there letting it all out. Finally, as I gagged my last bits, I came to attention and wiped my mouth off with my left glove as best as I could. Shouldering my rifle, I did an about-face and sharply marched back between the ranks. Getting back to my spot, I stopped, did a left face, took two steps forward, did another about-face, and snapped back to parade rest. I still felt like shit, but at least now I’d survive, the good Lord (and the major) willing.

Still, no one said a word. I had to admit, it had been a classy act. Finally, the major began talking again, finished his speech and then dismissed us. We fell out and the guys began to laugh their butts off. I just looked at them, turned around, walked back to the barracks, and collapsed on my rack. Luckily, the major did not come down on me. Another bullet dodged.

One day, an examiner from the AIG16 came up from Washington to inspect us. They usually came around to each unit every six months or so, mostly to make sure that we were following Marine Corps policy. They also over the years had become a private sounding block for us enlisted. When they spoke to us, we were free to voice any complaints or gripes to them, without fear of reprisals from our officers. This AIG, a major, inspected us in formation, and then later went through our barracks. No one had any complaints for him, and really, we did not think that it would make any difference anyway, and griping was not worth the risk of somehow it getting back to the CO.

He inspected our standing lockers. One guy, maybe in hopes of someday becoming a recognized hero, had found a photo of the Medal of Honor and had cut it out, being careful to cut the paper around the edges of the medal and the ribbon. He then took that paper cutout and taped it to the inside lid of his foot locker. When the AIG opened the door and saw that medal hanging there, he must have assumed that it was the real thing, because he immediately stepped back, snapped to attention, and smartly saluted the image. He turned to the guy next to the footlocker and made a comment about his having the Medal of Honor. That recruit looked at the AIG and fumbling his words, told him, “Uh sir, that’s not real, sir; it’s just a photo.”

We were all ready to crack up. I’m surprised I didn’t start laughing.

The AIG glared at him, and if looks could kill, that Marine would have been a dead man. Still, that AIG did not say a damn word. Finally, he turned around and stormed out of the barracks. We all just shook our heads. We figured that he must have thought that the more he made a big deal out of this, it would in the end be the worse for him. Better to leave well enough along and get out. We only laughed about it later on, when it was safe. Naturally, the photo of the medal hit the trash that night.

For a time, I did duty at Davisville, RI, six miles to the east, guarding storage facilities for the new Seabee facility.17 Mostly though, my assignments kept me in the Quonset Point area. While at times I did guard duty in the same location for a period of time, I often got different assignments.

It was at Quonset Point where I had my first round of trouble in the Marine Corps.

General Court Martial

I was transferred to the Naval War College in Newport in the late spring and did various guard assignments there. We stayed in wooden barracks located on a high bluff, about a hundred yards away from and above the channel, a few miles north of the city.

Staying out of trouble was getting to be a task for me, probably because I was so ornery. And there at Quonset Point, it seemed to be a common thing for us Marines. There were probably about three thousand sailors there and only some two hundred Marines. Still, at any one time, you would probably find about twenty Marines in the brig, and only a few sailors.

I had already been disciplined twice now. The first time was in March. I went out on liberty and stayed out too long. I got back an hour late, and because of that, I was charged AWOL. After a short hearing, I was busted down to private.

Then there was another incident a couple weeks later. We were at Davisville. A corporal was bringing three of us back to the barracks after we had stood our watch. It was evening, and as we passed the flagpole and approached the building, we saw the color guard preparing to lower the colors. Our corporal told us to hurry up and get in the building before they sounded the call “Attention to colors.” See, when that happens in the evening, if you are outside, you come to attention. When the bugler plays “Retreat,” you salute, and remain that way as the colors are lowered. You can go about your business again as soon as “Carry on” is played.

We hustled towards the building. Unknown to us, the officer of the day was watching us out the window from his office on the second story of the barracks. He got annoyed as he saw us hustling, trying to avoid standing for the short ceremony. Just as we neared the front door, the attention to colors was played. So close.

We turned around, saluted, and stood there until it was over. Then we turned around and went inside. We were met by that officer of the day coming down the stairs, really steamed. He walked up to us and started chewing our butts off. We hadn’t done anything wrong, but he hadn’t seen us stop outside, so he assumed we had not. The corporal told him that we really had stopped, but he didn’t believe him. And he didn’t give a crap what we said. Instead, we all got what they call a “deck court martial.”18 It was a bum rap, and we all had to do extra policing duties on the base for a couple weeks.

A month later though, I got into really serious trouble. I had been transferred to a guard unit in Newport. One night sometime after midnight, I became ill. I had had a few drinks that night, but I was not drunk. No, something else was happening to me. I had either caught some disease, drunk some bad liquor, or had eaten some tainted food. Anyway, I was pretty sick. Unfortunately, I was scheduled to go on guard duty in a couple hours. I struggled to get ready and walked outside.

Standing next to the truck loaded with sentries, all waiting to be dropped off at their designated posts, I pleaded with the sergeant of the guard to get someone else to take my shift. I had a temperature, felt queasy, and I was vomiting. Hell, I was dizzy just standing there talking to him. I told him plainly, “I can’t stand my watch. I’m sicker than hell.”

The sergeant sympathized with me, but said, “Well, damn it, I just don’t have an extra guy tonight here.”

I told him flat out that I would not be able to stand the watch. I could barely stand up, and that would not be for long.

He thought about it, and asked me, “Well, can you stand your watch long enough to post the rest of the unit? If you can, I’ll come back and bring a guy to replace you.”

My eyes drooping, I looked at him, sighed, and said, “Okay, I’ll try to hang in there.” So I got into the truck, and together with the other sentries, they took me out to my guard post, a small 4×4-foot shack that was next to a bomb storage lot. I began my 0200–0400 watch.

Standing there in the dark, I felt just terrible. I winced every so often at the terrific pain in my abdomen. I knew I had a fever and could feel the energy in my body draining away. Out there in the silence, I did not—I just could not—stand for too long, and slowly I slumped down some. An hour went by, although it seemed like four, and no one showed. The sergeant never came back.

I got sick again, to the point where I had to throw up behind the guard hut. Finished, I wiped my mouth off and came back to the front, weak and dizzy. Finally, feeling sorry for myself, I sat down on one of those storage crates next to the sentry box. All I could do was think about the sweet relief of just being able to hit the sack and just get some shuteye. Ah, just to be able to sleep it off in my cot. I guess I must have dozed off.

The next thing I knew, someone was shouting at me. I opened my eyes and saw a lieutenant standing in front of me. He must have walked up and seen me sleeping on watch. He yelled for a security guard, and under armed escort, I was taken to the captain of the watch. While the captain sympathized with me somewhat and agreed that I should not have been put on guard, he still was resolute in his determination and charged me with sleeping on duty. He then ordered me to the brig.

I was taken to a hut and put into a wire cage. I sat there on a makeshift bed made out of two boards, still sick as a dog, worried about the charge that had been brought against me. They could not bust me down, because that had happened back in March when I had come back late from liberty. They could though, charge me with sleeping on duty, and in the Marine Corps, that was a court martial offense. Asking around, I had found out that those Marines who had been found guilty of the charge were spending a year of hard labor at Portsmouth Naval Prison.19

I was to be charged with a formal GCM,20 although in my mind, I should not have even been made to stand duty, much less get charged. I spent nearly two months in that cage awaiting my hearing, at which time the charge was to be formally read to me. In those few weeks before the hearing, despite the fact that I had no access to facilities or anything, I decided that I was going to put my best foot forward. These bastards were not going to get the better of me. I figured that the best way to do that was to act like the Marine guard that I had been in previous months. We had drilled often, marched often, and when we were off duty, cleaned and pressed our uniforms. The brig was gonna make a lot of that difficult, but I decided I was going to do what I had been trained to do.

In the next week or so, I saw guys go in and out of the brig. Many of them were going to be processed out. Surprisingly, a number of them would sit there in tears, all broken up, crying about their fate. As I sat there, watching them feeling sorry for themselves, all I could wonder was, what the hell was so damn bad about being in the brig? I mean, it was just temporary.

I spent some time studying these young fellows. Most of them were barely old enough to shave and had probably sung in some church choir before the war had started. And when we got into it, I’ll bet they were the first ones to run down and join up, all proud and bragging about how they were going to save the country. Then they get to boot camp, see how rough it is, begin wondering what the hell they did, and then start to panic. Well, looking at these guys now, all I could feel was sorry for them. I guess that no one had told them there were no church choirs in combat.

During that time I exercised regularly, did not give the guards any lip, and made sure I cleaned up as much and as often as I could. At night, I’d remove my trousers and folded them between the two boards that I slept on. Naturally, each morning, they would not look as bad as they easily could have, and in the end, they stayed in halfway good condition, and I came out looking pretty decent.

At the end of that time, when it was my day in court, so to speak, I strode out of that cage with relatively pressed pants and a confident look on my face. Even the captain of the guard was impressed with me as I walked up to him like I knew exactly what I was doing and saluted him smartly.

I was taken to the hearing room and saw the captain in charge of the detachment. He was an old retired World War I veteran, one of the old guard, a retread who had been allowed to reenlist when the war had broken out. In a small room, the charge against me was formally read off.21 The officer in charge of the hearing was the same captain who commanded the Marine detachment.

I was quite relieved (although I did my best not to show it) to see at the hearing the sergeant of the guard on the night in question, and he testified on my behalf. He verified that I had told him I was too sick to stand my post that night but had tried to anyway. He further added that I had for months served as a very competent sentry without any incident, that I was certainly incapacitated that night from illness, and that I should not under any condition have stood that watch. The captain was impressed by my performance and admitted that there had been extenuating circumstances. In the end, I was found not guilty for that reason, probably one of the few that ever was let off for that type of charge. There was however, one condition: that I be transferred south to New River and from there, shipped out to a combat unit overseas immediately. My orders were to specify that.

Which was, of course, what I had wanted all along.

I readily accepted the findings, and the hearing ended. But I knew I had been shafted. They should have dismissed the charges and cleared my record as soon as that sergeant of the guard had admitted in his testimony that he had forgotten about me. After it was over, the old retread captain called me aside. He told me that he sympathized with me over what had happened and added, “You know, I’m gonna try to help you all I can.”

He added that even though I was being transferred from Newport to Camp Lejeune, he was going to try to arrange for my travel orders to read that I get there via my home town of Akron, Ohio. “So that you can get a chance to see your folks before you leave,” he said.

I thanked him sincerely for all that he was doing for me, and I promised him that I would not let him down overseas. Unfortunately, as it turned out, the captain told me the next day that he could not justify my detouring to Akron. It was just too far out of the way for them to justify it.

During this short time, getting ready to leave, I tried to at least catch up on what my buddies were doing. Jeff Watson, Jr. as it turned out, had joined the Marine Raiders. I found out in 1944 that he became part of C Company, 4th Raider Battalion.22 Another one of our buddies, Jim Olivera, ended up in K Company, 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines (K/3/1). Henry Rucker was still at Quonset Point. It sure was hard to keep track of friends in those hectic days.

As my orders to ship out were being processed, I must have seemed a pretty pathetic case, because two Marines in the administration office took pity on me. They took me aside and one of them said, “Look fella, you can’t possibly have any money, because you’ve been locked up for quite a little while.”

It was true. I only had a couple bucks in my pocket when I had been arrested, and because of the serious charge, I had not received any pay these last two months. The two guys were sympathetic, and evidently felt somehow that I was not a bad sort of fellow. They told me that if I needed any money, they would loan me some. Providing that I paid them back later, of course.

I felt humbled by what they had just offered. I mean, these two guys didn’t know me from Adam. I had just come off being charged with a court martial offense, and I was being shipped out. And yet, they were offering to chip in and help me out, not knowing if they would ever see me again, or if I would ever repay them. The bonds in the Marine Corps though, were strong, and I was starting to find that out. I thanked them for the offer and told them that I most certainly would pay them back. With that, they loaned me a few bucks—just enough to squeak by until my next pay.

It was a freezing, snowy day in December, 1942, when I boarded a train in Boston to head southward. I was on my own. All I had was my gear, my ticket, and the few bucks those two fellows had lent me. I had no idea what the new place would be like.

Camp Lejeune

The trip down along the East Coast was monotonous, and the train briefly stopped in Richmond for a layover. I walked around the platform, looking at advertisements. Even for Virginia, the December weather was cold, and as I walked around shivering, looking at some boxes stacked on the platform, I felt isolated. Standing there, reading some of the box labels, I again started to wonder what lay before me. I remembered the GCM, and how close I had come to going to prison.

On the other hand, I thought about the generous advance that those two clerks had loaned me and why they had done it. They had really taken a risk loaning me dough, and based on what I had gone through, they had no idea if I was really the type to return the money. I knew though, that one way or another, I would pay them back for their consideration and for taking a chance on me. Determined to weather this setback and wanting to be ready for what was ahead of me, I took a deep breath and went into the station to get warm.

The train let me off in Jacksonville, North Carolina, and I got on a small military bus, its only rider. The driver took me some twenty miles down, and finally we arrived at the new base, Camp Lejeune. Of course, no one called it that back then. It was just known to us as “Tent City,” because that was just about the only type of structure that was up there. I was directed to the base’s new barracks area, the New River barracks.23 When I arrived, I reported in to the top sergeant there. He looked me over and without saying a thing, he took me into his office.

I stood silently in front of his desk as he opened up my record. He looked at my papers and must have seen the GCM charge because he went “Hmmm …” and then glared up at me.

“Well I got news for you!” he barked. “You ain’t going to act up in my outfit now.”

The top then proceeded to read me the riot act, in detail. He ran a tight friggin’ ship here and by God, there sure as hell was gonna be no damn foolishness in his friggin’ command. Was that CLEAR?!? I had damn well better remember that my sorry ass was always going to be under his watchful eye, and if said sorry ass so much as slipped up even just a tad, he would bring the force of the whole damn Marine Corps down on my stupid worthless head. A whole world of shit would come down on me, and I, sure as God made little green apples, would not know what the hell had hit me. This by heavens was his Corps, and my worthless piece of horse-crap butt was not going to disgrace it.

I stood there, just took a breath and said quietly, “Yes, sergeant.”

Growling, he checked a clipboard and then assigned me to a bunk in the far corner of one of the cheap, plain plywood shacks that had replaced the tents in the area a year before. I found out that I was the first one assigned to this shack, so I quietly stowed my gear in the far corner, lay down on my rack, and relaxed, waiting for chow call.

About an hour later, I was half asleep when the door flew open with a crash. I looked up and along with a chilly gust of wind, in walked a Marine that somehow looked vaguely familiar. He saw me, dropped his seabag, and broke out into a big grin.

By damn, I thought, that guy looked a hell of a lot like Henry Rucker. Still half-asleep, I thought at first I was dreaming, or that my memory was playing tricks on me. But as the guy came towards me, I saw to my surprise and joy that it really was my old friend Rucker. Laughing, we greeted each other and gave each other a big hug. I welcomed him to our new barracks and helped him stow his gear next to mine.

This was just one of the good things about the Marine Corps that I was finding out. It was small enough that you were always seeing old friends or meeting new ones that had news of faraway places. We were just like a big family. I also would learn the down side of that over time when I would occasionally get news that buddies that I had shared many an adventure with had been killed fighting on this island or in that operation. The family thing in those cases made news that much more unpleasant to bear.

For the next two months, we took intensive light machine-gun training. The schedule was nice: one day training, one day off. Being a natural shot, I did well there. Rucker took to the training as well as I did, and we were soon both appointed squad leaders of machine-gun squads. For several weeks, we ran up and down those South Carolina hills, dragging our big old weapons around until they became part of us. We took them apart, cleaned them, and then put them back together time and time again, until we knew them inside and out.

There were a number of other advanced specialty training courses that I wanted to take, and I was older than a lot of other Marines there, so that gave me priority over them. I found out though, to my chagrin that I needed a high school diploma to apply for them. So I lost out on a lot of opportunities to advance my skills.

In the middle of my training, I finally was allowed seven days’ leave to go home for Christmas before I was shipped off to God knows where. It was Friday, December 18, 1942 when I began the trip home. Taking a suitcase with me carrying my dress blues, I caught the train. About ten miles east of Pittsburgh, the train made a stop, and always curious, I got out. I walked into a nearby pub for a quick drink, and that’s when my troubles started.

Taking my beer over to the window, I was shocked to see that the damn train was gone! It had left without me. And worse, my suitcase was aboard. I ran outside and spotted a railway supervisor next to a trolley. I told him that I was going home on leave before going overseas, and that I had been on that train. The supervisor told me to hop on the trolley, and we set off to catch the train at the next station. I mean, he opened that thing up as fast as it would go, and that damn trolley was really rolling, bumping all over those tracks, a stiff wind in our faces.

We just missed the train at the next station, just south of Pittsburgh. I jumped down off the trolley, thanked the guy, and took off running. I spotted the train and ran for it, but as I got near, it began to move. Frustrated, I had to wait for the next one. When it finally came, I went aboard and took it to Youngstown.

Getting off that train, I went in to the station and over to the line at the ticket counter to find out when the next passenger train for Akron was due. When my turn came, I asked the guy behind the counter what time was the next train to Akron was scheduled.

He looked up behind the window and said, “It’s just leaving.”

“WHAT?”

“It’s just leaving right now. That’s it over there,” he said, pointing out the window.

I thanked him and ran out to the track as the train began to move. The car doors were closed, but I sure as hell was not going to miss this train. I looked around and saw no one looking my way. So I quickly walked up past the rear cars and hopped up between two Pullmans. I got a firm grip, and held on.

The train gathered speed as I just stood there between the cars. Wearing my gloves and green coat, I was not that cold at first. But as the train continued, the chill began to set in. Within twenty minutes, I was freezing my butt off, wondering what the hell I was doing.

Suddenly, the back door of the car in front of me opened up, and a guy who was probably the train detective looked down at me. Evidently, someone had seen me climb up between the cars as the train had passed them and had phoned in the report.

The guy crooked his finger at me and said, “Come on in here, son. It’s too damn cold to be out there.”

Gratefully, I crawled over the coupling as he fully opened the back door to let me into the passenger car. I stood there, shaking. I assumed he was the train detective, but he said that he would let me ride into Akron. We talked a while as I began to warm up. He told me that there were worse ways to ride the rails in this weather. Even where I had been between the cars, it was a lot better than “riding the rods,” that is, riding on the crossbars underneath the car. He told me stories of some guys who rode the crossroads, even in the winter. I shivered. I could never do that. That was just dumb. He called them “cinder dicks,” because they rode next to the cinders along the track.

We pulled into Akron, and I finally made it to our house at 2941 Wingate Avenue, the last house at the end of the street, back by the frozen swamps. No one else could build there, because it was a flood plain, and every year the Tuscarawas River would flood at some point. Still, we lived there, and I had a nice stay with my family.

During my leave, I made sure that I saw my girl Phyllis, and we were able to have several nice evenings together. Her mom took a photograph of the two of us, which my brother gave to me years after the war. I also did get drunk a couple times. In fact, one night, I soaked up everything alcoholic that I could, because I knew that once I was shipped out to the Pacific that would be the end of the good times for a long time.

The days flew by, and soon it was time to say goodbye and catch the train to go back to Camp Lejeune. That turned out to be the last official leave I would get in the Marines. I returned to Camp Lejeune and took up where I had left off in machine-gun training. Besides getting to polish firing techniques, I spent weeks learning the proper care and operation of various types of .30 cal. machine guns.

I had one more brief chance to go home again before I was to ship out overseas. In late February 1942, our top sergeant told us that we would soon be headed west to join the war. Not totally heartless, he told us that if any of us did not live too far away and could convince him that we had enough money to make it home and back again, he would grant us a 72-hour liberty.

By then most of us only had a few bucks, and not enough for a trip home. So of course, being Marines, we improvised. A bunch of us pooled all our money together and gave it to one guy. He went in to see the Top, showed him the money, and got his leave. Then he came out and gave the dough to the next guy, who went in and did the same thing. And on and on.

That’s how each of us got to leave the base and go home. I wanted to see my mom again, but I also wanted to see Phyllis one more time. Those of us traveling north had it much harder, it being winter and all. I had to hitchhike, and man, it was icy cold. I managed to find enough rides to get me to Akron, but the last fellow I rode with dropped me off on the outskirts of town at 2 o’clock in the morning. It was so friggin’ cold. There I was in my dress blues and spit polish shoes, walking down U.S. Route 224 past the airport, in the bitter night, shivering, wondering what the hell I was doing. I would be able to get home just long enough to say hi to my mom, and maybe see Phyllis for an hour or so before heading back. Shivering, I walked down Waterloo Road, and finally made it home there at the end of Wingate Avenue. I could not stay long, but in the end, I felt that the trip was worth the effort, especially since I might never see them again.

American Samoa

I made it back to New River in time and continued machine-gun training. One day, just about the time I had established new friends and had become accustomed to our surroundings, in typical Marine Corps fashion, our top sergeant came into our shack and growled, “Okay, half you guys are shipping out overseas. So get yer shit together, cuz you’re leavin’ here in the morning.”

We packed up and early next morning, we headed towards a troop train that sat on tracks right there in the camp.24 We marched into the area and boarded the train from both sides. Rucker and I found seats next to each other in a middle car. We had no weapons with us. They had all been left behind in New River; even our rifles. It was just us and our kit, stowed in storage cars.