Into Combat

Like Henry, dozens of Marines were coming down with this typhus, and the command soon realized that unit efficiency was going down. My buddy the Swede always said he’d probably never see any combat, and he was right. He contracted the disease and was evacuated off of Goodenough Island. I only found out later that the Swede was sent back home. I would never see him again, in spite of my efforts to locate him after the war.

The division was losing too many men, and so we had to get off Goodenough Island soon. More and more of us were coming down with this deadly disease, or getting bit by rats. So we were going to be sent to a place called Finschhaven, located on the eastern side of New Guinea. This would be my first campaign.

Our entire division boarded these LSTs1 and left Goodenough Island on December 13th. We landed three days later on New Guinea at a place called Nascing, Alatu. Our role there was to be the reserve for the Australians, who were going to take Finschhaven at the eastern tip of Papua Island in New Guinea. The Australians had first landed on Papua on September 22nd, and had been fighting to take the area for almost three months now.2 As their backup, we stood by, ready to give them any assistance they might need.

We sent out daily patrols in our area to make sure there were no Japs around. We were located about a mile and a half to two miles from where the fighting was taking place. The Aussies had gone in a few weeks before, and in our defensive perimeters, we often could hear small-arms fire and artillery. We were later told by John Quinn, our company commander, that they had taken their objectives without too much trouble.

The Solomon Sea Area of Operations

During this time, we hiked around quite a bit, doing all kinds of training exercises. One of them was going out at night and just sitting. For three weeks, when it was dark, we went out into different parts of the jungle two at a time to just sit there for a couple hours, listening to noises and take notes on what we heard. Bugs, birds, wind … we were training ourselves to hear and identify what we were listening to. Often we could hear off in the distance the Aussie attacks. But as it turned out, they did not need us.

In the daytime, we either did gun drill or patrol exercises to get proficient at each. On bad rainy days, we would clean our weapons, but no matter what the weather was, we slept in tents. Us forward observers were given map-reading courses and map exercises. We were taught skills on using a compass to quickly get our bearings and blend them with compass results to find map coordinates.

I began to realize that being a forward observer was probably the best job in the battalion. I was only temporarily attached to units to do my job, and as such, was often on the move to find myself a new observation post (OP), which was just a new position for me to call in our mortar fire onto a target and to observe the results. I had my own field radio that I took with me, and then was set up by three or four other guys in our mortar platoon. I often had my own radioman whose only job was to make sure that I had a field phone that worked. We trained constantly. There was no sitting on our ass. We did a lot of hikes to stay fit, and we walked all over those jungles.

In the Pacific, I found out that each island had some common but also different types of wildlife, different types of fish, animals, and plants. On Pavuvu, there were fields of these weird types of sensitive plants. You could lay them down by just touching them with your finger.3 They had these long leaves, and when you touched them, they would fold and the plant would sort of lay down. Because of that you could see where guys had recently gone through. A couple hours later, they would pop back up and look normal.

After some nine days holding our positions and conducting patrols, we loaded back up on the LSTs and sailed off to get ready for our next assignment. So as far as I was concerned, Finschhaven had not been much of a campaign. We had not stayed there long, and we had seen no action. However, we had been close enough to hear the Australians fighting some distance away. That gave us some taste of what we would soon expect.

Cape Gloucester

Critical for Allied success in their push across the Pacific island was the neutralization of the crucially important, centrally located port of Rabaul, located at the northeastern tip of the island of New Britain in New Guinea. The Japanese had captured this excellent deepwater port at the end of January 1942, and had immediately begun building it up as a military center for their operations in the South Pacific. By mid-1943, despite the many air raids that the Allies had thrown against it, the area had grown significantly, and was now guarded by some 90,000 Japanese entrenched there. The port was now being used as the main forward base for units of the Imperial Japanese Navy and Air Force. From this strategic citadel, the Japanese were able to control all of their naval and amphibious operations in the Solomon Islands, the Bismarck Archipelago, and New Guinea.

Clearly, this enemy fortress had to fall or at least be neutralized. However, conquest would not be easy. The port was heavily defended, and an attempt to take it would strain the Allied effort to the fullest. Not enough resources were available for that huge an endeavor, especially with a number of critical naval operations going on in other parts of the Pacific and in Europe at the time.

So with a direct assault nearly impossible, the Allies chose instead to neutralize Rabaul. In the fall of 1943, considerable air operations by the U.S. Navy had crippled Japanese airpower and naval power in the area. The Allies now decided to at least threaten the port with a surprise landing at the opposite end of the 320-mile-long island of New Britain and slowly work their way eastward from there.

During this time, the division took the opportunity to conduct final training exercises in preparation for their upcoming crucial assignment: the invasion of New Britain. The Marines were going in on the western tip of the island to take Cape Gloucester with its vitally important airfield.

We were told that a place called Cape Gloucester was our next assignment. Ours was the preliminary operation to eventually take the entire island. Unlike at Finschhaven, the division would be in the thick of the combat, and this would be my first combat experience. Also, this would be the second combat landing for the First Marine Division: the first opposed landing had been at Guadalcanal in 1942, before I transferred in. The entire operation was to start on Christmas Day, of all times. We were told that, according to intelligence (which right away made us doubtful), the Japs would not expect us to land on a holiday. On top of that, we would be landing in their summer, when they get a ton of rain at that time, what they call the monsoon season. We would be landing at the start of it, another reason the Japs would also not expect a landing.

So anyway, one way or another, it was on. On Christmas Eve,4 at Goodenough Island, we boarded the LSTs, and later that morning, we left for Cape Gloucester at the western end of New Britain.5

Right after we got underway, several of the guys started to get seasick. Since I had never come down with that, I was fine. Our gunny though, seeing all these guys get ill, got furious with them and cussed up a storm. It did not matter to them, because they already felt miserable. The next day, though, the gunny himself got seasick, and we all, even those guys still nauseated, laughed our butts off.

We traveled north-northeast all day and on the morning of Christmas Day, 1943, we approached the western part of New Britain. We sailed some seventy miles through a strait,6 went around Cape Gloucester7 and traveled past it without incident. We sailed clear around the top part of the western tip of the island, turned south, and approached the island. We were to land at Yellow Beach, near the top of Borgan Bay.

Cape Gloucester Landing, December 26, 1943.

As we approached, we saw the pounding that the navy was giving. Finally the warships stopped firing, and several aircraft took over, bombing and strafing targets inland.

“Give ’em hell,” I mumbled to myself.

A few elements of the 7th Marines were already going in just before us to take the high ground. Our 3rd Battalion was getting ready to land in the bay, several miles southeast of the airport. We were under the command of Lt. Col. Joseph E. Hankins, who was an okay guy, I guess. I had not had much contact with him, but he seemed fair. I was told he was a little eccentric, and he enjoyed bringing his officers into their mess tent and making them stand for chow. Then he would tell them to sit there as he played guitar for them, but that was about all I knew. He did believe in his men, and once growled with pride that as far as he was concerned, every man in our outfit, even a lowly private, was capable of leading a rifle company into combat. I think that was something that could motivate me in the next couple years.

The monsoon season was underway, so naturally, it rained that day. The waves were rough as we approached the landing area, and luckily, despite the fact that we were close to shore, the anchorage was still deep. Because of that, the LSTs were able to get close to the beach. Some units landed in LCVPs.8 Our LST though ran right up onto the beach, grinding on the sand as it shuddered to a halt and the front clamshell doors opened up and the ramp dropped down. Hell, we were not even going to get our feet wet as we got off.9 Of course, that was offset by the heavy rain that kept falling.

Just before our LST ramp dropped, a sergeant in our group, nervous about the landing, had accidently chambered a round in his rifle and as we stood there, it accidently fired. The bullet ricocheted around the inside of the big compartment, startling all of us. We were up tight as it was, and the inadvertent discharge made it worse.

It was about a quarter after eight in the morning. The beach was called Yellow Beach, which, by the way, was not much of a beach. Several squads of infantry moved up, while my platoon started unloading equipment in the rain. At one point in the process, we actually lost a Sherman tank. Attached to the 7th Marines, it rolled down the ramp of the LSD10 and started out. It tried to make its way through the muck, and soon it got stuck in a swamp and just sank down out of sight.

I did my part. I slung my M1 and grabbed a cloverleaf of mortar shells.11 I carried the mortar pack down the landing craft ramp, onto the beach, and then inland to the ammo stack, which was about 50 yards away. Harry Owens carried a cloverleaf with me and stacked his next to mine. It all only took about five minutes, and we turned around and began heading back to the landing craft for another load.

We were walking towards the ramp when suddenly we heard approaching aircraft. We looked up and spotted two Jap planes diving down towards us to make a strafing run on the landing ships. We all immediately fell into the sand, as bullets zipped by around us. The Japs made two passes at us and then flew off. Harry and I stood up, brushed ourselves off, and went back to unloading.

There were several tanks and artillery on an LSD. They maneuvered the ship as close as they could to the beach and then fired artillery and tanks from it for gunfire support. Unfortunately, when it came time to fire close in, because of the height of the deck, they initially had trouble getting the guns to depress low enough for direct fire.

We kept hauling ammo, and eventually began taking the crates further inland. As we walked towards this thicket of bamboo and next to it was a big banyan tree. As soon as we cleared it, a machine gun opened up with a sharp krrrr! We could hear the bullets flying in, make clicking noises as they hit the bamboo.

Harry and I immediately dropped our crates and hit the dirt. My first thought was what were we to do? I don’t mind saying that I was definitely scared. This was the first time that I was being exposed to intensive enemy fire. I knew that it would happen, but on this operation, I had not expected to get shot at so quickly. Like everyone around me, we just hunkered on down. We were both scared, but Harry, his eyes wide with terror, freaked out, yelling and shaking. The firing stopped, and we waited until some infantrymen came up and cleared the area. Then I went back to unloading gear.

Eventually, we formed up and began moving out. We had landed about 10 miles from our objective: the town of Cape Gloucester and its airfield. The plan was for us to advance through the beach, make our way up along the coast to the airport, and then attack that way. The good news was that we would hopefully surprise them and overwhelm them. The bad news is that this was not going to be an easy operation, because there were no roads. There was nothing but this really massive jungle and bad weather. Okay, there was this one small trail along the coast, but it was narrow, primitive, mostly overgrown, and sometimes hard to find. That was it. No natives in the area; just a bunch of Japs, mostly in the trees. The enemy fire was light, but we quickly found out that there were several enemy snipers ahead of us.

We found out after we landed that there had been some kind of landing snafu. At least it looked that way to us. Typical. We had landed to the left of the remaining 7th Marines coming ashore, instead of to their right as had been planned. So the units of the 7th would have to move across our front, and we’d have to slant off towards the right. As we crossed through each other, filtering into our assigned units, all I could think of was what a target for the bad guys. I imagined that the Jap snipers were laughing their butts off watching us crisscross like that, thinking, “Look at those dumb asses.”

We cleared each other and began to move inland. Enemy sniper fire from the trees continued, and we took a few casualties. We ran across this one hut on sticks, and inside we found a Jap that had been wounded and was trying to get past us. He died in that hut.

As we slowly advanced northwest up that narrow coastal trail, we suddenly started to take machine-gun fire from our front. We heard later that K Company had unknowingly come up on a couple of camouflaged bunkers and a couple of machine guns had suddenly opened up on them. The company CO, Capt. Joe Terzi and XO, Capt. Phillip Wilheit, were killed right off.12 They took a couple more casualties, but all of the Jap bunkers were finally taken after we brought up an amtrac and covered it as it ran over three of the four bunkers and pounded them flat.

We kept moving, and sure enough, those damn snipers occasionally took shots at us nearly everywhere we went. Despite the snipers though, we slowly slogged our way forward. It was a stormy day, and I was soaked from the rain. It was hard walking because of the mud. And believe me, there was mud everywhere.

That day we advanced up the beach and along that narrow coastal trail, and that evening, we set up a defense perimeter at the edge of a field of tall grass. In front of us, we slashed several fire trails with our machetes to have clear fields of fire. Unfortunately, the grass was infested with rats and even worse, these tiny mites that turned out to be carrying scrub typhus, just like on Goodenough Island. We knew that it was 50 percent fatal to, so we tried very hard to keep the little buggers off of us.

As it got dark, we made our defensive perimeter, clearing fields of fires in front of us with our machetes. Some guy later walked up to Jack O’Donnell, who was doing sentry duty. Jack was quietly sitting behind a .30 cal. machine gun that he had set up. Jack did not recognize the guy, but that was not unusual. We had taken a number of replacements in the last couple weeks before we had boarded for this operation. The guy now walked up to Jack, looked around, and asked him, “Hey, where’s the front line at?”

Jack pointed in front of him and said, “It’s right out there.”

The guy turned around and started to walk that way, heading into the jungle. Surprised, Jack told him, “Hey, yer gonna get shot if you go out there!”

The guy did not say a thing and just kept walking. He disappeared into the night. It took Jack a while to realize that the fellow was probably a Jap.

In our unit were these identical twins: the Woodring brothers, from Paulding, Ohio.13 Now I was not too crazy about these two, especially since I could not tell them apart, and because of that, they had conned me out of some money. One of them had come up to me a week or so before we had landed and asked to borrow five bucks. I had given it to him, but when I went to get it back after payday, I had a problem. I asked him, “Hey, when are you gonna pay me my five dollars?” and the twin told me, “Uh, oh, you must have given it to my brother.”

When I later went to what I thought was the brother for the money, I got the same line. “Like I told you, that was my brother.” A nice little scam, especially since I could never catch them together, and I’ll bet I was not the only sucker that they had pulled it on.

That evening, we settled in for the night. We finished our defensive perimeter, munched on some rations, and fixed our sleeping spots. We knew it was going to rain, so we made sure that our hammocks were strung up off the ground. One of those Woodring twins had set his suspended between two tree trunks, about 10 or 15 feet from me. I did not have that option, so I had to set mine off the ground off a few tree branches stuck in the ground. It was uncomfortable and pretty unsteady, but at least it held up enough so that I could get some sleep. I carefully crawled in, flung the mosquito net over me, and despite a light drizzle, I finally dozed off.

Sure enough, this huge storm came on us.14 It had been pouring down for a while there in the dark, with lightning flashing, when suddenly, a large branch above us that had been hit by a shell broke loose. With a sharp crack, it fell and landed with a leafy-sounding crash next to me, right across one of the twins. The branch hit him square and took him right down, pinning him to the ground. Luckily for him, being suspended between the trunks and off the ground kind of cushioned the branch’s impact. Otherwise, if he had been near the ground (like me), the impact might have broken him in two. As it was, the impact crippled him up pretty bad, and the medics had to take him away.

We never saw him again (or my five bucks).

The next day, the 26th, as we started advancing up the coast, snipers again started to take shots at us. We could not figure how they knew where we would be or what path we were taking. Hell, we didn’t even know where we were gonna be, but somehow, they were always around us. The closer we came to the airport, the more intense the sniper fire was. Finally, our battalion commander, Lt. Col. Joseph Hankins, decided to just ignore the damn snipers and to keep moving towards the airfield. So that is what we did. Still, we did shoot at them if we had any opportunity, which I guess was just as well, because they sure as hell were taking potshots at us, and they seemed to be all around.

At one point, we began taking sniper fire from this big banyan tree that was at the other side of a 100-yard-wide grassy field. He was invisible in that damn tree and every time we tried to move or anything, he would crank off a shot. As we moved forward, we started to get worried. We figured that if he kept plunking away at us, sooner or later, he was gonna get a few guys.

Finally, irritated, I told a Harry and Corty, “Damn it, we’ve just got to do something.”

The three of us decided that we were going to go get that sonuvabitch, although Harry was scared as hell. We started crawling through that tall grass to get close to the tree. Now this banyan was massive, with supporting branches all around the main trunk.15 As we moved in, we scoured the branches. Once or twice he took a shot at us, so we knew he was still there. We would just have to flush him out.

I whispered to the other two to spread out (especially since I didn’t want Harry with me; the guy was spooking out). We separated and began to crawl closer to the tree. We slowly positioned ourselves around it, one on each side, and one guy up the center. We sat in the grass and waited for him to take another shot so that we could locate him. We sat there for some time, waiting for him to fire. But he did not take a shot. Evidently, he had seen us moving up on him, and did not want to give away his position.

Suddenly, a BAR opened up from the other side of the tree. Evidently, another Marine from one of the rifle companies had had the same idea. He fired two bursts, and sure enough, the Jap came sailing out of the tree and onto the ground. That ended our anxiety, and we returned to the trail.

The next day, the 27th, even though this terrific storm hit us, we gathered our gear again and started heading northwest. The rain came down almost horizontal. Normally we would have called it a cloudburst, but the damn thing did not let up, and often the rain came down in buckets. Still, we kept going up the coast through heavy mud, moving slowly up towards Cape Gloucester, with our battalion in the lead, occasionally taking sniper fire.

Finally that evening, off in the distance ahead of us, we spotted a Jap defensive line, located about a mile or two from the airport. It effectively stopped our progress. The enemy line on its extreme left turned into a butt of land that jutted out into the ocean. All along the line, the Japs had dug in an organized line of resistance. Until then, we had just come across some harassing sniper fire. This, though, was a determined stand that they were making to defend the airport. The whole line centered on this 75mm naval gun that they had set right in the middle.

As it got dark, we approached the enemy line, and as we moved closer, we started taking heavier small-arms fire, and some 75mm shells starting to come in.

Lt. Col. Hankins decided to take the position on the flank instead of attacking head on. He wanted to hit it immediately, but word coming down the chain of command was for us to delay until the next morning. We were thankful for that, and even though it rained that night, we managed to get some rest.

The next morning, we prepared for our attack.

Although Lt. Col. Joseph E. Hankins’s idea to take the main line by attacking its flank was sound, it was estimated by the senior officers that the enemy position was too well fortified and had too interlocking a network to be taken easily. Therefore, the division commander, General Rupertus, ordered the attack be delayed until the next morning, so that additional support could be mustered. Rupertus immediately ordered his reserve, the 5th Marines, to come ashore and support the effort. He also called in additional artillery fire missions and air support for the upcoming assault.

The next morning, December 28th, it was raining as artillery from the 11th Marines began pounding the enemy line. They were supported sometime later by Army A-20 air sorties over the line. The Marines were getting ready to attack when another delay was ordered. This was to allow two platoons of M4 Shermans to move up to provide fire support. The process of getting in place of course was slow for the tanks because of the mud and the heavy jungle, so it took some time for them to get into position. Finally, at 1100 hours, Hankins’s 3rd Battalion began their assault, with I Company and the Shermans in front.

We began moving up for our attack at 11 a.m.16 on the 28th. The 1st Battalion was going to outflank the enemy and hit them in the rear. Our 3rd Battalion was given the thankless task of hitting them head on.

We prepared for the assault, and finally the word came down to move. Our mortar crew was set up, and the enemy positions pinpointed. I was assigned as a loader on one of our platoon’s 81mm mortars.

We started lobbing shells as the riflemen advanced, and shortly after that, the enemy opened up on us. The assault slowed down as the riflemen moved up from cover to cover. Then the Shermans came up and the couple Jap 75mm guns took them on. The one in front of us though, was no match for our tanks, and where I was, I could barely see the Sherman, but it took that gun out pretty quickly. With that, the rest of our battalion stormed the enemy lines in a direct assault. After four hours of battle, we finally took out the Jap positions and captured the enemy line and what survivors were left fled into the jungle.

After this big assault on what we ended up calling Hell’s Point, we secured our position. In the meantime, we kept firing mortars and artillery at the Japs that were retreating onto the airfield.

I spent all the battle and half of the night loading mortar shells. Hell, I must have dropped well over a hundred rounds down that tube. My arms the next morning were really sore. Unfortunately, because of our position and because the damn jungle was so thick, we could not see much of what was going on. We could see smoke rising in the distance where the shells were falling, but we could not tell if our mortars were effective or not.

The next day, we carefully walked around the enemy pillboxes and positions and examined them. I noticed that nearly all the Jap equipment that was not made out of metal was made out of leather. That included belts, pads, bags, and other stuff like that.

In front of us, along the main Jap defensive position, we got to look up close at that 75mm gun that had given us so much trouble. It was a naval gun, with a couple of seats on it for the operators.17 In front were these cranks to traverse and elevate the barrel. The Japs had put the gun at this section of the line to stop the assault and to stop our tanks, but instead, it had been taken out by that one Sherman. After that, taking the rest of the positions had been relatively easy.

Now that we had taken their line, I walked up to the gun, and saw a couple dead Japs hanging from the spot. One of them was sitting in one of the gun’s two seats, blood all over on his shirt, his arms down, his mouth open, his eyes glazed. Flies were already buzzing around his corpse.

We checked the area around the gun and found that this line of defense consisted of a couple dozen prepared Jap positions on each side of the naval gun. These positions were small, camouflaged four-foot-deep spider holes fortified around the front and sides with coconut logs. They sat about a foot above ground, and each had a lid that they crawled in and out of. The Japs sat in them and fired rifles out these slits in front. We had overrun them quickly, as a matter of necessity. After all, there was only one way to destroy it. You either killed them firing through the slit or by tossing a grenade. From the flank preferably, but you attacked them frontally if that was the only way. In this case, it had come down to that, since the 1st Battalion in their outflanking maneuver had gotten bogged down in swamps and bogs. So the only way we could get these bastards was head on. And it was a feeling I will never forget, because as scared as we were doing it, I was surprised to realize afterwards that it also was quite an adrenaline rush. Combat can do that to you.

We looked closely at each of these nests flanked out along both sides of the naval gun, mostly just to make sure that the Japs inside were dead. We found two bodies in each hole, and I was surprised at what I saw. In most of the positions, one or both of the Japs had evidently committed suicide. You could tell that they had by the way the bodies were positioned. Since the Japs were so short and none of them had pistols, the only way that they could kill themselves was to take off their boots, point their rifles into their mouths, and squeeze the trigger with their big toe. And that’s how we found many, with their boots off, their heads splattered, and their rifles pointed the wrong way.

We talked about this that night. Evidently, the Jap soldier thought that if he died bravely in battle, he would go to heaven, or whatever the hell they believed was up there. So why had they not tried to die fighting us, instead of killing themselves? The only thing we could conclude was that they were scared shitless of us Marines. These guys must have believed what their propaganda had told them about us: that if they were captured by Marines, we would do unspeakable things to them. So when their buddy next to them was killed in combat, they actually out of fear of capture had chosen to commit suicide. This was even more surprising because doing that, they ran the risk, however slim, that word of their suicide might somehow get back to Japan, and their families would not only be dishonored, but in most cases, mistreated because of this shame.

I remember shaking my head once or twice. These buggers were sure as hell not helping their country that way. And I remember concluding that day that the story I had learned about the fearless, intrepid samurai warriors that the Japanese soldiers were was just a myth. Many were certainly not as brave as everyone thought.

I also realized then that we were going to definitely win this war, because you cannot win by committing suicide. What Patton had said was right in this case: you do not win a war by dying for your country; you do it by making the other bastard die for his.

After we took their main fortified line, their will to fight seemed to collapse, and there was little resistance after that. There were still skirmishes and occasional firefights, but nothing very serious as we moved up the coast towards our objective. After four days of combat, on December 30th, with our 3rd Battalion on the left and 1st Battalion on the right, we overran all the enemy positions at the airfield and took it. We raised the flag, and we all cheered.

We stayed in our position for a few days, building our defenses, regrouping. We found Jap bodies all over the place. A couple days after the battle, we tried swimming in this little river. Then it started raining, and soon Jap bodies started floating downstream. After a week or so, we were given the nasty job of burying their bloated corpses. They were everywhere: in the jungle, on the trails, in foxholes, in the streams; bodies surrounded by these big black flies, with maggots all over them, and they stank really bad. That sure as hell was no fun, and the smells made us gag.

Looking for bodies, one day I came across this little hill with about seven dead Japs on it, dead for weeks. They must have been Mongolians or something, because they were big fellows. Hell, this one guy looked like he was almost seven feet tall. I never saw such a big sonuvabitch in my life. From what I could see of how he lay, it looked like he had got shot just as he began charging down that hill. The others were all scattered further down.

Another corpse sat in a foxhole, still holding his rifle. It was a nice little .25 cal. piece, and I thought to myself that it would make a nice souvenir. Despite the terrible stench, I decided to take the rifle before I covered him up. I bent over and held my breath and pulled. I finally wrenched it loose, but when I did, the rifle came up with his hands still clenching the damn thing, and the stink that came with it was overpowering. Dizzy, I gagged, feeling like I was going to pass out. I stumbled and damn near fell in on top of him.

Reeling, I shook my head, grabbed that damn rifle and its “extras,” and pitched it. Still retching, I tapped the corpse down with my shovel, quickly threw some dirt in the hole, and got the hell away from there to get some fresh air.

I finally recovered and went back to my grisly job. We found that we could not drag the bodies to bury in graves or holes, because they were too rotten and stank. All we could do was cover them up wherever they lay or possibly roll them into a trench. Oh man, did they stink.

We did this until we got all the Japs we found on that one side of the airport. I think to this day that that was one of the most tasteless jobs I ever had. Somewhere along the line, as we buried these bastards—who knows, I might have got it from one of them—I developed this fungus in my ears. I had seen fungus growing on my body a day or two before, but now it was in my ear. We had been playing cards, and all day I had noticed a slight ringing in my ears.

Finally, after I shook my head again, one of the guys said, “Peto, what the hell are you doing?”

I told them, “I got a ringing in my ears.” Also, my ear was tickling. I mean, I really had this itch.

About an hour later, it started hurting and I decided I had to go see Doc. I went over to where he was in sickbay and he looked in my ears. “You’ve got fungus,” he said.

He took a thin piece of wire and wrapped a small wad of cotton around it, kind of like a Q-tip. Then he soaked the cotton in some sort of lavender liquid. He picked up this swab and then began to corkscrew it into my ear. He scraped off some goo that must have been in there as I flinched in pain. He finally took the swab out, wrapped the wire in some more cotton, soaked it, and then did it again. Doing this, he managed to scrape that fungus off, but wow, did it hurt, and occasionally I yelped in pain as a sting jolted my head. A pain like that, in your ear, through your brain, to me is the worst place to feel it. He carefully scraped all the fungus off, and then he made me come back the next day (which I damn sure did not look forward to). Then three days later, he scraped my ears again. As much as it hurt, I finally managed to get rid of it.

Besides the Japs and the wet crappy weather, one other interesting feature that was a constant in our day and one that worried us from time was, of all things, an active volcano.18 This was a strange thing for me. When I had been out west before the war, I had seen a lot of mountains, and a few of them were old volcanoes that had been active hundreds or thousands of years ago. But this was the first active one I ever saw. And it wasn’t that far away, either. It was located about five miles southwest of where we had landed, and there was always some gray smoke coming out of it.

Every morning when we got up, the first thing we did as we walked out of our tents was to go take a leak. We’d stroll over to the latrine and as we did our thing, we would be facing that way and look at that big old cigar, with smoke coming out of it like some kind of a natural chimney. If the smoke was no thicker than the day before and we didn’t see flames shooting out of it, we figured that we had made it through another night and went about our business of fighting the Japs.

As we consolidated our positions around the airfield, we seemed to not have any significant air support, although aircraft occasionally flew around in our area. Still, some innovative fellows came up with an ad hoc solution. We had been given several observation planes to use. So the guys hit on the idea of using them as half-assed bombers. The pilot and observer filled their planes with grenades and dropped them as they flew over suspected Jap positions—the kind of stuff that those Marines did in the old banana wars down in Nicaragua in the twenties and thirties.

Of course, the Japanese returned the favor, and we would find ourselves on evenings getting bombed by Jap planes from nearby Rabaul. And then of course, there was always “Washing Machine Charlie.”19 He would come in around midnight and fly over us for an hour or two, before he finally dropped his one bomb and headed back home to Rabaul. The bastard never really hit anything; he just kept us from sleeping a lot.

The rain came down on us daily, sometimes in heavy downpours, making it hard to see things around you. Brooks turned into streams, and streams turned into rivers. Everything was always wet, and there was mud everywhere. Any semblance of a trail disappeared in soaked quagmires, while vines and underbrush made our forward progress very slow, so that we often had to struggle through the heavy jungle, sometimes hacking off branches in our way with machetes. You really can’t see in the jungle too well, and it’s hard to tell what the hell is going on.

We carried bayonets on one side of our pack and on the other side our machetes. We mostly used these at sunset to cut down areas of heavy grass to create fields of fire, so that the Japs could not easily sneak up on us. I know in the movies they show guys hacking their way through the jungle with their machetes, but that’s just Hollywood. Usually we just walked around the heavy brush. Besides, if you just tried to hack your way through the jungle, you’d just wear yourself out. No, the machete was mostly just to cut the fields of fire at night.

We took breaks along the way, but it was almost impossible to get comfortable, sitting in the rain like that. Warm food was nearly impossible since fires were near impossible to start, although we did discover that the waxed paper around our K-rations burned nicely. Meals were miserable, and whatever we ate was soaked.

Sleeping was a real challenge, especially with those damn netted jungle hammocks (hopefully between two trees, and not sticks). One night, I was lucky enough to set mine up between two tree trunks in a clearing. It had rained some, so the ground was just one big marsh. I took my trousers off—I slept nude, because my underwear had rotted off of me days ago—set my hammock up, unzipped it, managed to crawl in with my blanket, zipped the mosquito net back up, and relaxed.

Naturally, about ten minutes later, I had to take a leak. Now sailing on the Manoora had confirmed to me that I was no good maneuvering a hammock. But the ground was just too damn messy to go walking around in the dark. So I unzipped the net, leaned over, and managed to get myself in position. And there I was in the middle of the night, doing a balancing act in my hammock on some damn island in the middle of nowhere, trying to take a piss. Suddenly, the whole thing struck me as funny as hell, and I started laughing my head off (it didn’t take much to get me going). The more I thought about it, the funnier it got, and the more I cackled, waking guys up around me and everything. Naturally, I finally lost my balance, and guess where I ended up.

For two weeks after we had secured the airfield, the entire division stayed busy cleaning up the area. The word was that General MacArthur himself was going to come visit us. So we picked up trash, rotten coconuts, tree limbs and stuff, and cleared out jungle paths. But mostly we just buried Japs. Guys with kerosene and special equipment went around spraying puddles around the camps to kill the mosquitoes and other bugs.

Now I was no fan of this army bum to begin with. I had really been upset ever since I had heard that when he left the Philippines in the spring of 1942, he had decided to leave over a hundred nurses behind, and many of them were sick, and instead had taken all his furniture with him.20 Now we were cleaning up for his visit. Finally, at long last, the day arrived, and we stood on a high bluff as we watched the destroyer that he was supposedly on approach the island. The destroyer pulled in and docked.

Exactly a half hour later, the destroyer pulled out again. We were stunned. All that preparation and he had not even come ashore to see us. Man, were we pissed off.

I spent something like four months at Cape Gloucester, a good part of the time in some sort of combat, either moving up on Jap positions, or chasing the bastards all around that damn island. And I think that the worst part of it was that it rained almost every damn day. In one month in particular, it rained for 30 straight days. I remember one day after that, we were on patrol and the sun actually came out. I was shocked, happy, but shocked.

I grinned, turned to my buddies, and pointed to the sky. “Look, guys!” I shouted. “The sun’s out!”

They paused and we all looked up. Just that fast though, the sun slipped away behind some dark clouds and disappeared for good.

“Thanks for jinxing us,” Skoglie grumbled.

Soon after we took the airfield, we were told that the Japs were killing missionaries up the coast, and we were ordered to go up about 80 miles and take care of the situation. So our whole battalion loaded up onto a half dozen LCTs21 and sailed along the northern coast of New Britain for about a hundred miles up. Our mission was first of all, to cut off the retreat of any Japs moving east from Cape Gloucester. Second, we were supposed to wipe out the Jap patrols trying to kill the missionaries.

We landed at this dock and were met by this Australian who lived there. He oversaw the coconut plantations for the industry owners on the island, and also doubled as a coast watcher. Working for him were these crews of natives that he had hired. He was to be our contact for the area and our liaison with the natives. Up the coast a short way was this little village, and the Japs had been harassing the people living there. So we were told to go up there, start patrols in that area and take out any Japs we found. The Australian assigned a couple natives to act as guides for each of our units, and so we started patrolling with one or two of them with us. Because they knew the area so well, it gave us a huge advantage in checking the jungle out.

We set up in a camp that had been laid out for us, and the next day we started more patrols to find those Japs bothering the villagers, and to pick up any stragglers coming from the western part of the island.

Naturally, we took advantage of making friends with the natives. They lived in these small shacks that were no bigger than the size of a two-hole outhouse back home, and all of them were perched on these sticks. Several of their little villages had been abandoned. One we saw had a really fancy front entrance. The guy that had lived there must have been a hunter. He had killed several huge wild boars, and had mounted their tusks around the doorway.

One thing I noticed is that these natives barely wore any clothing at all. They had no footwear, and the only clothing the men wore was this wide woven belt, with a sort of two-to-three-inch-wide rectangular apron thing hanging down in front to, you know, cover their dingus. That’s all that they wore. After a while, we decided that we were going to go them one better. So we took everything off. Shoes, socks, shirts, underwear. We were going around nude.

Well, we could see that a few of the natives didn’t like the idea of us going around like that. Through that Aussie interpreter, we found out that they insisted if we wanted to go around like they did, we would have to put one of those aprons things on too. So we did, in order to keep them friendly, and to keep up our image as fair-minded Americans. Personally, I think they insisted that we wear them because they saw right away that we Marines had bigger wangs than them, and they didn’t want their native women to try for a better time. Of course, those male natives would never admit that …

While we were up there, I got to take advantage of the scenery. There were lots of tropical birds on the island, and you could often hear them cawing and squawking. And the water … I had always been a good swimmer, and now it came in handy. I waded out into the surf on a number of occasions and went swimming around the reefs. At times I could dive down some 20 feet or so and swim underwater around the beautiful coral that shimmered in the light, and that glowed in these fabulous colors. Of course, I didn’t have any scuba equipment or anything. It was just a matter of holding my breath and down you go. Still, usually alone, I had a great time out there.

Of course, I saw a lot of fish, and so I got this practical idea to my adventure: food. I went fishing the efficient way: I took a couple of hand grenades and went out into the surf. I tossed a grenade out, it went boom, and up came the fish. That night, we had fish for supper, and man, it tasted good.

A couple of the natives added to our cuisine as well, and over time, they taught us how to fish. There was this one fellow who would go out into the shallows and dig around the bottom with his toes. Up would come a shell. He would look at it and determine if it was “ripe” or not. If it was, he would toss it out onto the sand. When he had a few of them, he would come out of the water, collect them and then take them over to a fire he had built and toss them in. After they had cooked for a while, he would pull them out, and we could suck the meat out of the shell. They were pretty good eating, too. I don’t know what those shells were, but they tasted good. And anyway, I figured that if he ate them and didn’t get sick, they were okay for me to eat.

Over time, our relations with the natives improved, and pretty soon, they were wanting to do stuff for us. They began to single us out and adopt us. It got to where one or two would hook onto to each of us and hang around, ready to do stuff for us. So, for instance, if I stood up and got ready to move out, my pair would pick up my pack and rifle for me and carry them along behind me.

It was funny. One morning soon after we had arrived, we had morning formation, and when we fell out of ranks, we turned about and there was a native behind each one of us. Our officers decided that this had to stop. But those natives wanted to join us.

Nighttime was interesting. When it was dark, huge flocks of these giant vampire bats flew above us, through the treetops. We never really saw them, just black blurs that sailed overhead through those big trees, flapping their wings and making squeaking cries. A couple guys were terrified of these things, believing they would swoop down, slash at our throats and turn us into vampires.

One night, we decided to shoot down a couple to see what they looked like up close. When a bunch of them flew over us, about twenty of us were lined up and ready, and so we opened up with our rifles at the same time. We must have shot off a hundred rounds of ammo, and in the end, only one damn bat came down. So much for our expertise at being crack shots.

We checked out this giant flying thing that we had shot. It really was huge, and I was impressed by its size. It measured over six feet across, with about a three-foot wing span on each side. While the body of a typical bat is the size of a mouse, this one was like a really big rat. I shuddered to think of flocks of these things swarming down on us.

We stayed for a month or so, cleaning out the Japs in the area, working with the natives and exchanging food with them: rations for seafood. I remember one day, one of those big native wooden canoes came up to the dock with the natives paddling. As it got close, we could see that there was a really nice native girl standing at the bow, with only a grass skirt. She was topless. You know, it was the custom. And man, she was well built. She had a nice set of jugs. For us sex-starved Marines, that was really a sight, and all we could do was stare. And she was right at the bow of this canoe, in plain sight and everything. Of course, it had to end.

All of a sudden, the native in charge—one of the Australian’s assistants—saw her at the bow, and he let out with a yell. He started hollering at those guys in the canoe. Obviously, it was about the girl, because they immediately began to furiously paddle on one side, and that canoe spun around in just a few seconds, and man, all we saw was its back end as they took off. We never did find out what he screamed at them. Probably that we Marines were nuts and that we’d rape all of them.

Because it rained so much and this was a tropical environment, everything got moldy. Our uniforms could not take the weather, and soon our trousers and shirts began to rot, literally off our bodies. Our boots began to fall apart as our laces slowly shredded. Trench foot became common. On top of that fungus stuff in my ear, we had to put up with malaria mosquitoes, rats, and bugs carrying all sorts of neat stuff like that scrub typhus. Oh, and did I mention the ants? Red ones, black ones, big ones, little ones, millions of those nasty little things.

The 11th Marines Battalion commander said it right: “Hell, on this island, even the damn caterpillars bite.” Yeah, we were all getting to be in bad shape.

Around February 5th, before we went up the coast, one of the last things I did was go exploring with John Skoglie. We went over to where the 7th Marines had advanced to our left, hoping among other things, to kill a wild boar, A sergeant a while back had killed these two boars, and the meat from them fed just about the entire battalion. We wanted to do the same thing, so there we were, out hunting. We walked through really heavy jungle, and soon we could hear the damn things moving about. We ran across their dung all over the place, but we could not get close enough to shoot one.

We eventually came across an area where the 7th Marines had fought an action. We slowly walked through the battle scene and saw all kinds of stuff. We found parts of various weapons, some ammo, hand grenades, and a few 60mm mortar shells. We also found a muddy boot with the foot still in it. It was a GI issue.

We decided to get rid of some of the ordnance lying around as per directives that had been given to us. This was mostly so that any stray Japs that came by would not be able to get their hands on it and use it. For a while we had a great time, throwing grenades down below and watching them explode. Sometimes we threw them at the same time, and other times one of us would throw a grenade just after the other. We had been doing this for a while when Skoglie pulled the pin off another pineapple and tossed it away. This baby, though, happened to hit a big tree just to his right, bounced back, and landed at our feet, the fuse burning.

I saw it land and immediately flipped backward over the log that was behind me and scrunched down. Skoglie saw it too and did the same thing. A few seconds later, the grenade went off with a loud wham! Dirt and grass rained down us. The danger over, we both popped our heads up, looked at each other, and started laughing. We looked at where the grenade had fallen, then at each other, and laughed even harder.

A while later, we were wondering how to destroy the 60mm mortar rounds. Skoglie reminded me of this story we had heard about an army fellow in Italy named Commando Kelly. Someone had written this magazine story about him, and in it, this guy had dropped mortar shells out of a second-story window onto some German tanks below.22 We figured that if this Kelly guy could do it, we could too. So we took some of those rounds and carried them over to this steep cliff.

Standing at the edge, we dropped two of them and looked away. Nothing but two shells clanging on the way down and thudding into the ground. So we tried dropping another. Then another. We couldn’t get a damn one to go off. We sure dented the hell out of the casings, though. We later went back to the area and blew up the rest of the ordnance lying around.

Pavuvu

After the Cape Gloucester operation, instead of heading back to Australia, we were told that we were going to be shipped back to Pavuvu, at the northwest end of the Slot.23 Our battalion boarded the USS President Hayes24 and left New Britain on April 24th. We arrived at Pavuvu four days later.

We found a spot of clearing that was our assigned area and began to unpack. We were told some good news: we were no longer under the Army’s command. We had been transferred out of General Walter Kruger’s Sixth Army and were being released back to the authority of the navy for the next operation. Naturally, everyone in the unit was glad. Screw the Army. We figured that the president liked us Marines, partly because we always got the job done, but also because one of his sons was an officer in the 2nd Marine Raider Battalion.25

The bad news though, was that Pavuvu was sort of like an undeveloped resort area in Hell. There was no accommodation, and conditions were to say the least, primitive, even by Pacific islanders’ standards. Hot, humid, tropical weather, no buildings, no latrines, and no place to bathe. If you wanted to shave or wash, your helmet had to do. There were plenty of inhabitants on the island, but none that we cared to mingle with. There were rats and bugs of every make and model, including these big nasty, biting ants. On top of all that, there were these small black crabs that came out at night and got into everything. And there were no civilian bars, and, of course, no women. Definitely not Melbourne.

Grumbling, we set up our tents and tried to make the best of our new home. We went on working parties to clean up the area where we were staying and make it better livable. Quite a job, because it was a mess of jungle, infestations, and rotten coconuts.

Hell, even the simple act of taking a dump was an experience. We would dig a long slit trench for a couple companies. The trench was too wide to straddle, so you had to sort of perch your butt over the edge and do your thing. Naturally, etiquette was observed, so that you did not tick off some guy to the point where he would “accidentally” bump you over and down into the trench. When you were done, you covered your crap with a shovel full of some slaked lime. Later in the morning, after everyone had done his business, we would cover the crap up with dirt, as well as the damn crabs that fell into the trench.

It was while I was on some of these early working parties there at Pavuvu that I became acquainted with another Marine who had gathered some fame as a film star. His name was Bill Lundigan.26 We first met him aboard ship on the way to Pavuvu. He had been in a dozen or so movies before the war, even as recently as last year, before he decided to enlist in the Marines. Now a combat cameraman, he also was in charge of our movies at night, while we sat on the coconut tree logs and watched. Last year, Bill had starred as a Marine in some movie about the early part of World War II in the Philippines,27 and there were a couple scenes where he was mowing them down. So we would rag him by calling him “Jap Killer.”

A couple weeks after we arrived, we started to receive a few reinforcements, and at night, I would either write a letter home, watch Bill’s movie of the week (again), go off exploring, shoot the bull with the guys, or sit alone and think about stuff. I sometimes thought of Henry. Was he still alive back home? More likely, he was buried in some lonely grave on Goodenough Island. And what about the Swede and others? What had happened to them?

The campfire gave me no answers.

In early 1944, we were assigned a new regimental commanding officer: 46-year-old Colonel Lewis B. Puller. Halfway to becoming a legend by that time, he would go on to become the only fellow in Marine Corps history that would be given five Navy Crosses over his career. Today, he is considered by most in the Corps as the quintessential Marine. Having joined the Marines in July 1918 as a private, he had over the years gone up through the ranks as a maverick, until he carried the rank of full colonel and commanded the 1st Marines, my unit. To us, he was not just a great leader—Col. Puller was sort of a celebrity, since during his career he had worked closely and directly under what were today a number of very senior general officers, including four-star Admiral Chester Nimitz28 and four-star General George C. Marshall.29

Col. Puller we soon found out was a gruff, brash leader, and he always spoke his mind, often peppering his words with some really salty language. He had taken over command of the 1st Marines at the end of February 1944, so I served directly under his command for some seven months, although I was around him for nearly ten.30

Somewhere he had picked up the nickname “Chesty” because he had this big barrel chest, and oh man, did he show it a lot, especially because he often went around without a shirt. We were, after all, in the tropics. Anyway, the name Chesty went with his type of aggressive personality. Even though he had this moniker, no one ever called the Old Man that. I mean, ever. This was not just because of self-preservation. We had too much respect for the man. His fellow colonels and the division commanding officer General Rupertus called him “Lewie.” We just referred to him as the Old Man, the Skipper, or just plain sir.

Col. Puller’s reputation preceded him. He was very popular with us enlisted, mostly because he had once been enlisted too, and he was always sharing what was going on with us. It didn’t matter if we were in combat or in the chow hall, he was always there. You could be pinned down by enemy fire, and you’d turn around and see him behind you, often exposed to snipers, assessing the situation, talking to someone about getting fire into an area. There was a standing joke that it was a bad idea for the guys on the line to sometimes hesitate before advancing onto a position, because one guy might turn around, see Col. Puller standing next to them staring, and gasp, “Holy crap. There’s the skipper. Let’s move out and get the hell out of here.”

He was a tough CO, but you could tell that his men always came first. And there were so many stories to back that up. One of the most popular ones was about the time he noticed this private saluting over and over to no one. Puller walked up to him and asked him what the hell he was doing. The private told him that he had forgotten to salute some lieutenant, who had ordered him to salute a hundred times as punishment. The colonel took the private over to the officer and told the lieutenant that a good officer always returned a salute, and so every salute the private gave was to be returned.

That’s the kind of guy the skipper was.

Although our generals thought it would be a nice rest area, Pavuvu was a miserable place, what with the damn crabs, the rats, and the gazillion bugs all over the place. It smelled terrible from rotting coconuts. Oh, and the weather was tropical heat, which made for very uncomfortable nights. It was so different from those freezing cold nights back in Rhode Island.

The layout for the regiment was simple. The outdoor “facilities” were crude. Each company had two sections of tents, with the officers in one area, and we enlisted in the other. Similarly, the officers ate in their own mess tent, and we had our own. Main paths going all over were stomped out of the ground. Our officers, because they were officers, often got better “cushy” accessories than we enlisted, but Col. Puller had little stomach for that. He had a soft spot for the enlisted man and at heart, he was really one of us. To him, we were all one unit.

I remember one time when we first came to Pavuvu, a number of our officers managed to get mattresses for their cots. They weren’t huge thick things, but they did make it more comfortable to sleep on. Well, after several of these officers managed to get one, Chesty put out a regimental order: all mattresses were to be turned in immediately. When the officers protested, the colonel growled at them, “If there ain’t enough mattresses around for everyone to get one, then no one’s gonna get one.” I will be honest, it was amusing to see these lieutenants and captains grudgingly grab their mattresses and take them down to the base quartermaster and check them in. They were to remain there until enough mattresses could be given out to every man in the regiment. Which of course, never happened.

By this time, I had been placed in the 58-man heavy mortar platoon in 3rd Battalion’s M Company (M/3/1). Now the Model M1 81mm mortar was the biggest and most formidable weapon that a Marine rifleman battalion carried; a buddy of mine, Russell Diefenbach, called them our “infantry cannon,” and with the proper crew, this weapon could put out some serious firepower. Not including the shell that it fired, the mortar consisted of four parts.

First there was the base plate, which was a 45-pound, thick, heavy metal rectangular plate. It was what the weapon was mounted on. The barrel itself, in which the shell was dropped, weighed another 45 pounds and pivoted off the base plate at a set angle of anywhere from 40 to 80 degrees. The bipod which set the angle of fire and included the aiming device, weighed about 46½ pounds. Last, the weapon came with one or more aiming stakes. Now these were simple 1-inch-round wooden poles that were painted white, with black rings evenly spaced along each pole. Whenever a gun crew could not see any of the targets because their vision was obstructed, they would pound one or more of these stakes in the ground around the mortar and then use them as directional aiming devices to help them provide the unit accurate, although indirect, fire.

The platoon was commanded by a platoon leader, an assistant leader, and a gunnery sergeant. It was made up of two sections of two heavy mortars each, an ammunition team, an observation team, a communications team, and a couple of navy corpsmen, for a total complement of 58 men. While every one of us in the platoon was trained on operating these 81mm mortars, those who were not on the four gun crews received special training in their specific roles.

True to his word, Haggerty made Rucker and me two of the platoon’s four forward observers (FOs), so we also received special training on spotting enemy targets, figuring out ranges and bearings, and then calling down the direct or indirect mortar fire on them, either by field telephone or sometimes by using those damned unreliable walkie-talkies.

I initially knew nothing about directing mortar fire, and while I learned that you can be trained as a forward observer, there was no school for it; hell, there wasn’t even formal training. It was a matter of word of mouth and experience.

I quickly learned that it was difficult for anyone to accurately estimate sizable distances across any sort of broken landscape. It was especially hard to do in the jungle. Most guys could not do it well—could not estimate range. They didn’t know whether they were looking at 50 yards or 200 yards. It had to pretty much be a God-given talent: you either had it or you did not. As it turned out, happily for me, I really had it. I’m sure that my years of experience as a hunter helped quite a bit, but the fact remained that I could figure out distances quite well. I do have to admit though, that it would take me three campaigns before I became an expert at it. Still, I can say with pride that I never dropped a short round.

Thus, I began to better learn my job as an FO. It was up to me to direct the fire of our mortar battery. As such, it was my job to go forward with a rifle company to find a good spot to direct the mortars, so I essentially had no purpose when we were on the move. Sometimes, our platoon leader would go with me, but usually he did not. When the riflemen stopped and set up a defensive position, I had to as quickly as possible find the best spot to observe where I wanted the fire placed. I soon learned that this was often difficult to do in jungle environments, where it was hard to see what was in front of you. Having a good eye for distance, the knack of figuring positions out by using my senses, and a keen sense of direction, helped tremendously. I discovered not to rely on what I could see, but also to listen to sounds and above all, to get myself in a good position where I could see a smoke round land.

Once I had found me a good spot, I would notify the platoon, and our communication guys would then run a set of wires to my position to attach to my field phone, and then leave me a spare set of batteries.

When the lines were set and connected, I was in business. If a fire mission was needed, I’d flip up the butterfly switch on the field phone and call into the network. My call sign became “Xray,” and after a while, every officer in the battalion knew who that was. It was nice to have friends in high places.

I am proud to say that our mortar platoon was, in my mind, one of the best mortar platoons in the Corps. We could set up our weapons in minutes while the ammo was set out and the field phone set up, and I don’t mind stating that I did quite well developing into a crack forward observer, usually getting our mortars onto the target within a couple rounds.

We trained for combat a good deal, and still, nearly every morning we were inspected. After chow, we would clean up as best we could and then fall out in formation with our rifles—we all had rifles, even the guys in the heavy weapons units, because every Marine was a qualified rifleman. We would be called to attention when our platoon commander came by, and then he would slowly begin going down the lines. As he passed each one of us, we would smartly bring up our rifle to port arms and open the breech for him to inspect the weapon for proper working order and cleanliness.

On Saturday, this became a semi-formal affair, and these inspections were special, because we were usually reviewed by the Old Man himself. He did this every Saturday for all the months that led up to our next operation. We would prepare ourselves that morning, and around 10 a.m., Col. Puller would come by. And since this was a true inspection, he would do us the honor of wearing a shirt.

While these Saturday inspections were semi-formal, they were to a certain extent somewhat informal as well, so we did not have to stand in formation or anything. Our rifles were not inspected because that was done every weekday morning by the platoon commanders, and if he checked those as well, he would have taken forever to go through the entire regiment to closely inspect each rifle. So we would leave our rifles in our tents. We instead would have our mortars disassembled, cleaned up, and laid out before us: the base plates, the tripods, the barrels, and the aiming stakes.

One time we had, as we did every weekend, prepared for him to inspect us, so we had all our equipment ready. That Saturday morning, as usual, we waited in our tents, because it was another hot day. When Col. Puller was spotted heading our way, someone snapped, “Here he comes.”

Gunnery Sergeant Long bellowed “Fall out!” We ran out of our tents and over to the equipment. Each of us ran up to whatever piece of equipment we happened to go out to, came to attention, and stood there. Normally, as the forward observer, I was tasked with properly positioning the weapon’s aiming stakes or using the field phone. But this morning, we just lined up willy-nilly, and I ended up next to our No. 1 mortar’s thick steel base plate.

As Col. Puller walked by, he remained silent, looking at us, eyeing our equipment. Normally, he would stop every so often and say something friendly to one of the men. The colonel often did this during any kind of inspection, although I will admit that whenever he passed me, he would sometimes just smile at me. The skipper came along, inspecting the mortar components, and soon came by our section as we stood there at attention.

When he came to me, he stopped. He looked at me at my short thin frame and that big heavy rectangular base plate that was next to me. Then he glanced over to my buddy, Clarence Keele.31 This guy was a Texan, and like all of them, Clarence was huge. He was a mean-looking, rugged, tough John Wayne kind of fellow, towering at six foot six inches and weighing about 270 pounds. Quite a contrast to me, a foot shorter and just 125 pounds. Clarence was standing next to me, holding a light wooden mortar aiming stake. Col. Puller again glanced at me and the base plate at my feet. Then back again over to Clarence standing with those puny aiming sticks, and then back to me again. He must have figured that my job was to carry the big heavy plate around, he smiled at me and said, “What are they doing son, picking on you or something?”

I just grinned back and totally intimidated by the man, I didn’t say anything. He just smiled, shook his head, and went on. Obviously, the colonel had a sense of humor.

By June, the division was back up to strength, and we were trying our best to make Pavuvu survivable. We went back into training, and practiced to the point where we could almost fire the mortars in our sleep. Although I was an FO, sometimes I still went back to loading. For the first two campaigns we still took time out to train. We all took turns. Each guy had to know each job.

One of the weapons that the Japs seemed to be using effectively was what we called a “knee mortar.”32

Using good old American know-how, our own guys were trying to rig some kind of a mortar weapon that could be shoulder-fired, like those weapon-development idiots were doing back in the States.33 For that reason, one day, our battalion armorer took a spare 60mm mortar and rigged a stock for it, with a trigger to a firing-pin device. After making sure that it was all securely attached and hooked up, our company was asked to try out the new weapon. Whoever fired it would probably have to be braced for quite a kick. So Ernie Huxel, the gunner for the No. 3 81mm mortar, was the guy we chose to fire it, because he was one of the burliest guys in the platoon, with muscles all over the place. A few of us went with him out to an open area for the trial test-firing. After some instruction by the armorer and some joking around, Huxel grabbed the weapon and got down into a prone position. After checking everything out once more, he carefully aimed the weapon and then fired it.

It went off with a loud cough, and sure enough, the recoil of the damn thing was tremendous, especially because Ernie was in a prone position. Therefore, his entire body was behind the weapon, so his shoulder absorbed the full force of the kick. The whole mortar whirled up out of Ernie’s hands, went sailing into the air, twirled around, and fell back onto the ground with a clanking thud. Ernie was thrown back and rolled over on the ground, groaning, clearly in distress. We could tell that he was hurt. It’s a wonder the damn thing did not break his shoulder.

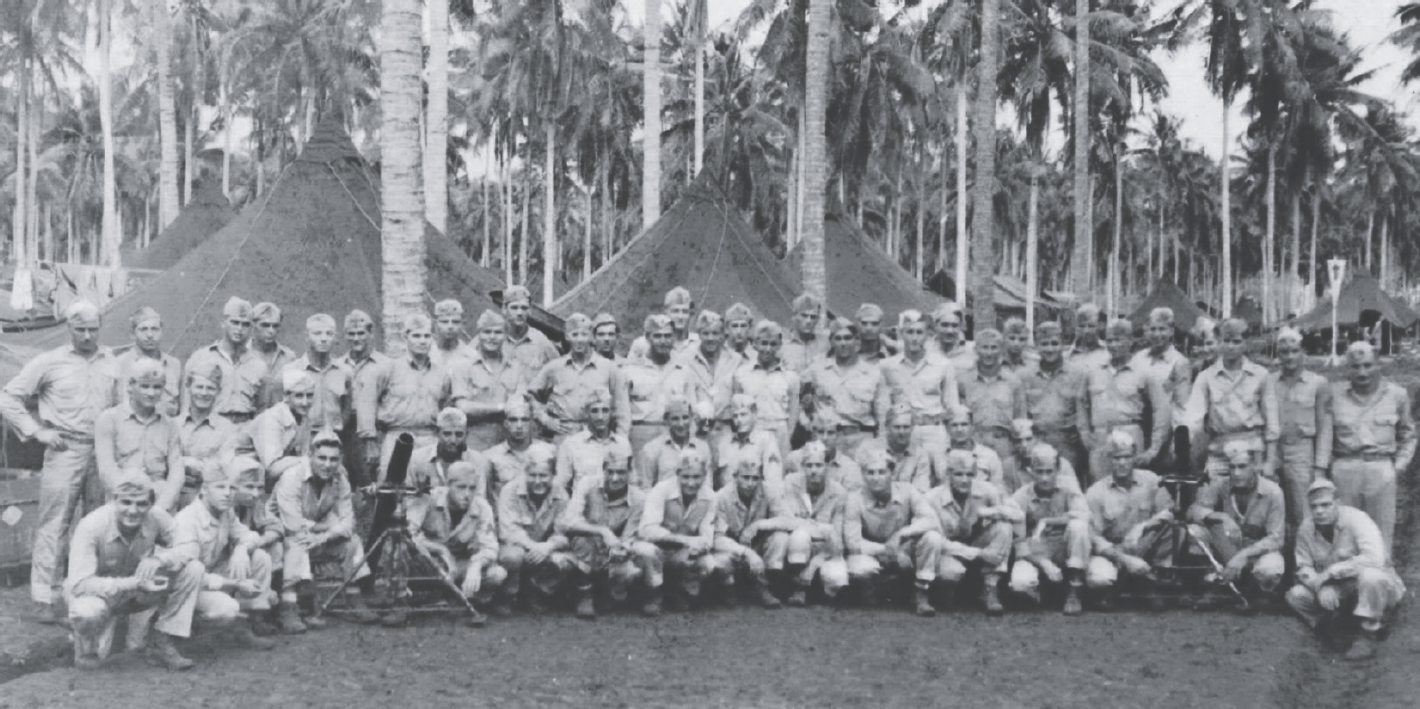

Part of 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines on Pavuvu, August 1944. Henry Rucker is shown squatting in the bottom row center, directly below the palm tree. George is to the right of him. In a little over a month, over half of these men would be dead or wounded. (Author’s collection)

So much for innovation.

In addition to our regular training, each of our standard Marine regiment went through a reorganization, which included disbanding each of the three battalion heavy weapons companies: D Company in 1st Battalion, H Company in 2nd Battalion, and my own M Company in 3rd Battalion.34

Up until now, the heavy weapons company had consisted of a headquarters section, three heavy machine-gun platoons, and our own 81mm heavy mortar platoon. The headquarters section was dissolved, and the three heavy machine-gun platoons were distributed onto the three rifle companies, as had been the light 60mm mortars. For 3rd Battalion, one platoon each went to Company K, Company I, and Company L. Our mortars became reassigned to the battalion’s headquarters company. So of course, procedures for our fire missions were now different. This of course, allowed me to more closely integrate with the battalion officers, and ultimately gave me higher exposure in the battalion’s operations. I would also more freely move around from one company to another for the best fire observations.

We slowly made Pavuvu somewhat livable, and our training went on and on. Sometimes, some of it seemed unnecessary. By now, I had accumulated a number of MOS codes in my Service Record Book.35 My primary code of 645 (Forward Observer–Fire Control), 604 (machine-gun crewman), 607 (mortar crewman), and 870 (Chemical Warfare NCO), which I had acquired in training at Quonset Point. And of course, there was MOS 745—rifleman, a code that every enlisted Marine carried.

Socially, there was not much to do. Living in tents together, we got to know each other. So many of the guys I had known in the Cape Gloucester operation had been transferred. One nice thing though, was that one of my old buddies that I had joined up with had been transferred to the 3rd Battalion before me. My Portuguese friend Jim Olivera was with K Company, and we at least got to see each other once in a while. I just sometimes wished I could hook up with some other old friends.

We did have a couple interesting things happen. Once when we were sitting down to noon chow, some idiot decided to clean the grease off the concrete deck with gasoline. Naturally, the fumes filled the tent, the flames from the stoves ignited the gas, and there ya go. Instant panic as we ran out of the tent. The flames rose and the tent collapsed. The whole thing was burnt to a crisp and of course, we all cheered. All the officers ran over to find out what had happened. Col. Puller just shook his head and said, “Do you guys hate the belly robbers that much?”

One day, as I was shooting the bull with a couple of our mortar crewmen, I spotted a strange-looking lad come into camp. This guy was a pale fellow and really thin, but as he came closer, there seemed something vaguely familiar about him. He was pretty much bald, except for a few straggly hairs growing out of the top of his head. As this gaunt figure swaggered up the company street, that nagging feeling that I somehow knew him grew. My jaw dropped as I realized that the odd-looking creature I was staring at was none other than my old buddy, Henry Vastine Rucker.

“Henry!” I yelled as I ran up to him. Man, he had lost a good deal of weight from the scrub typhus fever, and his complexion was a pasty yellow; nothing like that Southern tan he used to carry. As fragile as he looked though, I gave him a big bear hug and he smiled as I stood squawking about how great it was to see him again. I had figured he was dead, and now there he was.

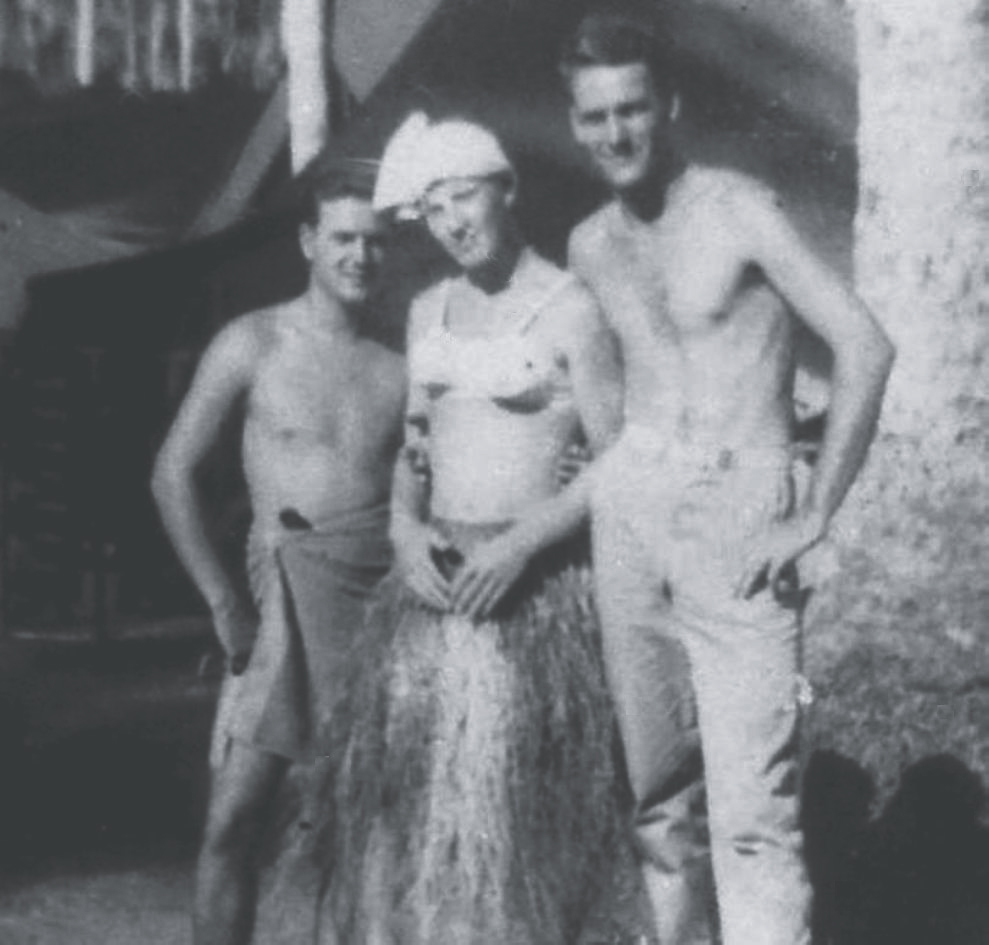

George’s friend Henry Rucker in a grass skirt, taken on Pavuvu sometime in August 1944. (Author’s collection)

We went over to my tent and he pitched his gear there. He told me in detail about how he had struggled with the typhus, how terrible it had been for him. I felt sorry for him when he told me how embarrassing it had been to have little or no control over his bowels.

We could not figure out why they had sent him back to the unit instead of returning to the States, because supposedly, scrub typhus was supposed to leave you with a bad heart—if you survived, of course. Evidently, his must have checked out good enough to keep him in theater, and they needed replacements badly. Still, I was just happy as hell that he was still alive.

I filled him in on what had been going on, and the landing that was coming up. Henry had joined us just in time for the Peleliu operation.

We immediately thought about how we could celebrate his return and what kind of brew we could get our hands on to toast the occasion. Unfortunately, all we could come up with were a couple big bottles of Aqua Velva. That night we found that while it made a damn good shaving lotion, it left something to be desired when it came to being sipped, even after we had filtered it through a couple dungaree shirts. So we mixed it with water and Kool-Aid so that we could at least get it down. We finished making our improvised brew, and soon after a couple weird-tasting drinks, the two of us were giggling like schoolboys and having a ball.

About an hour later, I realized that I could not lift my left arm, and groggy now, I concluded that I had sipped my fill. I staggered over to my rack and collapsed on it. Henry couldn’t get to his. He was passed out on the dirt floor.

My hangover the next morning was—wow. And for the next three days, every time I belched, I swore that I could smell perfume. I vowed that I would never ever use (or drink) shaving lotion in any way, shape or form ever again.

1 Landing Ship Tank. These were shallow draft vessels designed first by the British and later put into mass production by the United States in 1942. Their purpose was to give the Allies the capability to move and land men, equipment, vehicles, and supplies across the ocean and land them onto irregular shores. The LST featured a large ramp built into the bow to allow the unloading of trucks and mechanized vehicles. A typical LST displaced nearly 4,000 tons loaded, and could make about 12 knots. Fully loaded, it only carried a maximum draft of about eight feet (three and a half at the bow). Most were lightly armed, typically with a 3-inch gun and several mounted machine guns, and carried a crew of about 100. During the course of the war, many were converted into other functions, such as repair vessels, hospital ships, and a few even carried light reconnaissance craft that were loaded and unloaded by cranes. While LSTs were constructed also in the British Commonwealth, the U.S. by far exceeded all of them, eventually constructing about 1,000 LSTs. Most of those that survived the war were later either scrapped or put into mothballs.

2 On December 3rd, a detachment of Combat Team B left Goodenough for Cape Cretin near Finschhaven, followed on the 11th by the rest of the 1st Marines and all its attached units.

3 The plant is called mimosa pudica (from the Latin word pudica, which means shy or bashful). It is sometimes referred to as the sleepy plant or shy plant. Technically a creeping annual or perennial herb, a part of the pea family, its leaves fold up and droop defensively whenever they are touched or moved. Minutes later, they will slowly re-open. They also close up at night.

4 It was Christmas Day in the United States.

5 The convoy was recorded as leaving at 0600.

6 Dampier Strait.

7 The Japanese had no artillery in the area to challenge any vessels running the strait.

8 Landing Craft Vehicles & Personnel. Also referred to as “Higgins boats” after the designer, Andrew Higgins. This was a small landing craft used a great deal in amphibious operations during the war. Made of plywood and light metal, this 4-man craft with its shallow draft could bring ashore a 36-man platoon. With a 9-ton displacement, it was 36 feet long, 10 feet wide, had a maximum draft of 3 feet, and could make almost 12 knots. Over 20,000 were built during the war.

9 George was lucky again. Many Marines on other LSTs were not though, and they desperately tried to keep from drowning as they stepped off, loaded with their equipment into three to five feet of heavy surf.