The Palau Islands.

Along with the Marshall, Mariana, and Caroline islands, the Palaus (called “Parao Shoto” by the Japanese) just west of the Carolines, had been occupied by the Japanese for decades. After they had declared war on Germany in 1914, the Japanese Navy had sent a force to occupy the islands. After the peace treaty was signed, these annexed islands were awarded to Japan in 1920 as a mandate* by the newly formed League of Nations. Japan, in turn for being given wide-sweeping administrative powers, was tasked with “promoting to the utmost the natural and moral well-being and social progress” of the islanders. Since then, Japan had assumed all the land rights of the islands; the Palaus had been developed by the Japanese into a formidable base, with the island government located on the small island of Koror near the center of the chain.

Throughout the 1920s, Japan became increasingly fascist as dissent within the country was more and more suppressed. In September of 1931, Japan, now controlled by the military, initiated a bold expansionist plan by invading Manchuria. The League of Nations finally declared Japan the aggressor and demanded that occupied Manchuria be returned to China. Japan refused, and in late February of 1933, it withdrew its delegation from the League of Nations, but brazenly retained its island groups as the de facto sovereign. At the same time, it closed these mandates off to the rest of the world.

In the early part of World War II, the Palaus became a forward staging area from which the now formidable Imperial Navy had furthered Japanese influence down into the Dutch East Indies and New Guinea. By 1944, they had further expanded the Palau island chain into a major supply center and had turned them into a Pacific main line of defense for the Japanese Home Islands.

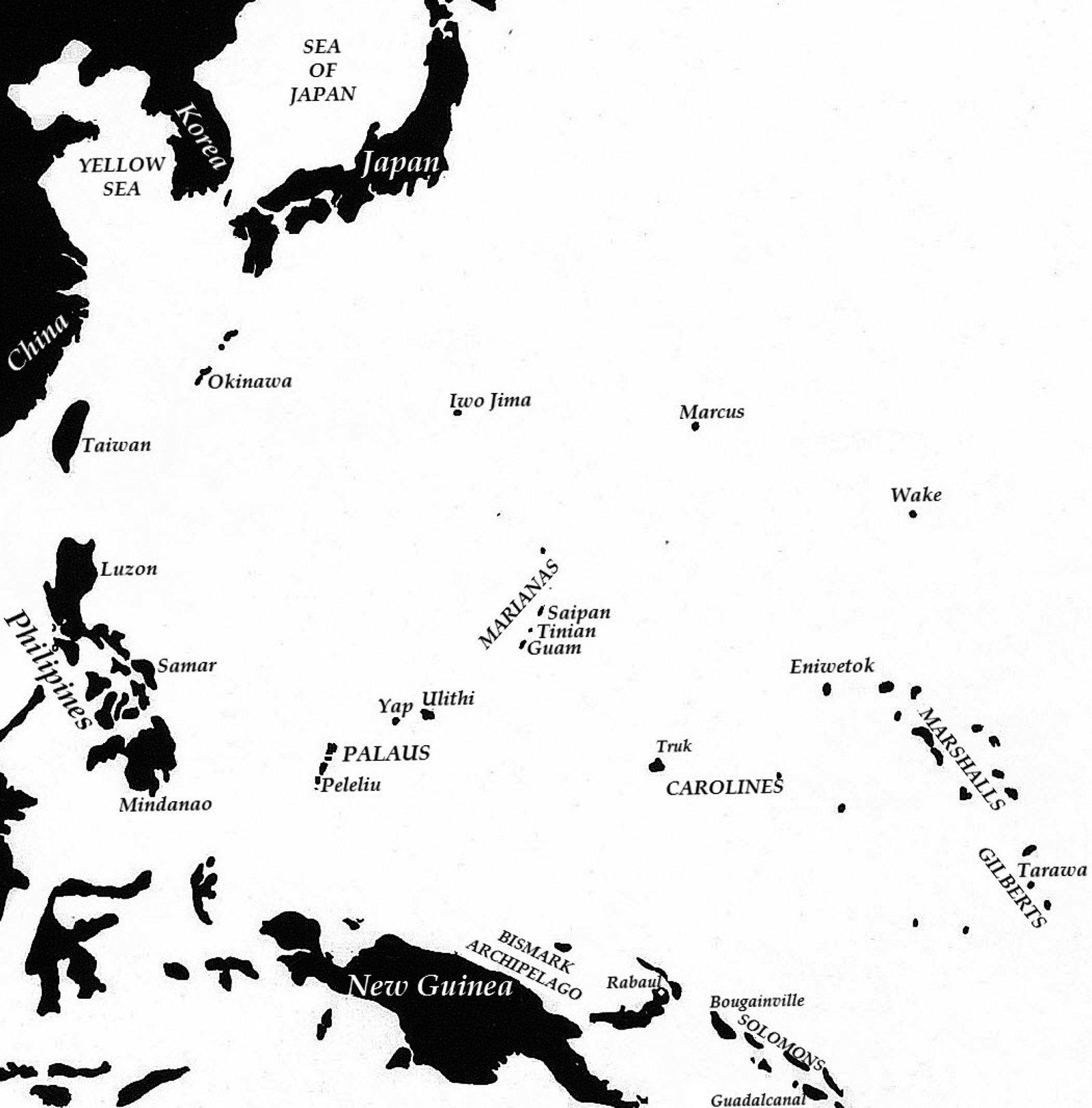

The Palaus are a multifarious group of over a hundred tropical islands and islets of about 189 square miles of land. Located some 825 miles southwest of Guam and 2,000 miles south of Tokyo, they are oriented roughly north-northeast to south-southwest for about 80 miles. This remote tropical island group in the western part of Micronesia has its own language that includes several different dialects. Average rainfall is over 140 inches a year, mostly coming in the summer and early fall. Temperatures average in the 80s, although they frequently top 100°F (38°C). Humidity averages around 82 percent.

The five main islands in the cluster are, north to south: Babelthuap, Koror, Eli Malk, Peleliu, and Angaur. Babelthuap is by far the largest, about 125 square miles, and about ten miles wide. Nearly all of them are surrounded by an offshore barrier reef of coral. Most of the others are small islets or atolls, many just an acre or two in size. Just north of Babelthuap, between it and Ngajangel Island to the north, surrounded by broken reefs, is a large, triangular-shaped, natural, deep-water lagoon known as Kossol Passage. Some 12 miles wide, it has very few shoals and is large enough to be used as both a temporary anchorage and a seaplane operating area. Its only drawback is that, exposed on all sides, it offers no protection from the weather, with high winds resulting in large swells.

The southernmost island, Angaur, is about seven miles southwest of its nearest neighbor, Peleliu. It is shaped roughly like a crescent, somewhat like the top of a classic baby carriage, with the hood facing Peleliu to the east. Angaur is about two and a half miles long and less than two miles wide at its widest point. Its terrain is much flatter than Peleliu, with its high point only about 200 feet above sea level, although there are several wooded coral ridges at the northwestern corner. Like Peleliu, the island was mostly made up of thick jungle. The Japanese had over the years built a number of phosphate strip-mines on the island, interconnected by a narrow-gauge railroad. There were several wide beaches suitable for landings, although the most ideal were on the southwestern and northeastern shores.

The innocent-sounding Peleliu (called “Periju” by the Japanese) lies strategically some 450 miles east-southeast of the Philippines and 650 miles north of New Guinea. It is the second-to-last southernmost island, about 23 miles from the capital island of Koror in the center of the chain, and 27 miles from Babelthuap to its north, by far the largest and northernmost Palau island.

Peleliu is somewhat shaped like a lobster claw, which is why in the planning stages, the Americans often referred to it as “the lobster claw island.” This small coral-limestone island is less than six miles long and a bit over two miles wide, measuring only about 6,400 acres in size. The eastern arm of the island is much shorter than the western one, which is about two miles long. Between them lay several marshes and mangrove swamps.

The geography of the island in 1944 was slightly different from its present shape, but its topography has essentially remained the same. Most of the island—barring the Umurbrogol massif northeast of the airfield—is level and except for the northern end, which was either open terrain or coconut groves, the island was either thick with jungle or wet with marshes and mangrove swamps. For most of the southern part, Peleliu is more or less flat, and, except for the beaches and the fairly large airfield, was originally covered with thick jungle, brush, scrub trees, and a variety of mangroves and swamps. There are no natural water sources on the island.

The beaches on the southwestern side of the island and on the southeastern tip were open, and could be considered possible landing areas. The beaches on the southwestern side totaled about 2,600 yards in length, with the southern end just 1,600 yards from the southern tip. Here the distance to the barrier reef ranged from 400 yards on the left, to 750 yards in the center, and 550 yards on the right. The beach at the southern end was much narrower, with a number of coral outcroppings along the edge. Each beach area was ringed by dense jungle, including a concentration of coconut, mango, and palm trees.

The airfield was located in open terrain just north of the southwestern beaches. It boasted two long runways, each about 50 feet wide. The longest, running parallel to the island’s longitudinal axis, was 5,500 feet long, the other, perpendicular to it, was 3,800 feet long, and the topography was such that both could easily be extended for larger aircraft. The airfield also featured a hard surfaced, 2,700-foot taxiway that connected the runways, the turning circles, and the service aprons.

Begun in 1938, with some 3,000 Japanese and 500 Korean military personnel, the airfield included a large, cinderblock control headquarters, several metal buildings, and dozens of other structures, including a modest communication building, machine shops, quarters, fuel storage, and a small power plant. The airstrip was well developed and big enough to accommodate large strategic bombers. Thus, it was considered by the Allies as a strategically important objective for the entire maritime area, and therefore would be a major factor in the decision to invade the island.

The Palau Islands.

At the time, Peleliu and Angaur combined carried a small population of about 300 natives. Unlike the tens of thousands on Koror with paved streets and electricity, these locals lived comparatively simple lives, subsisting on fishing, communal gardens and small livestock.

There are a number of coral-limestone hills located at the northwestern and eastern tips, and two promontories at the far southern end. Just northeast of the airfield though, is a feature strikingly different from the rest of the island’s topography. This is a jagged cordillera that runs up the spine of the island for about three miles. The natives call it “ Umurbrogol” the Japanese called it “Momoji,” and the Marines would acrimoniously come to christen it “Bloody Nose Ridge.” This small massif is a dense chain of pinnacles, treacherous ravines, ridges and defiles almost a thousand yards wide, with slopes that rise to 550 feet above sea level, well covered with brush and low vegetation along the sides and tops, and with thick jungle along the gulches. In among all this were countless numbers of caves, both natural and manmade, with many being old phosphate mines. The Japanese had engaged in a major defensive program to modify, expand and reinforce these, as well as create new ones that were often connected by narrow tunnels.

Peleliu is surrounded by an offshore coral barrier reef. In some areas such as the northeast, it has a steep gradient, while in some sections like the western side, it is broader. The distance between the reef and the shore varies, from 1,500 yards in the northeast, to almost a mile and a half in the north, to only 300-400 yards at the southern end.

Since the United States’ sudden, jarring entry into World War II in early December of 1941, the American plan for victory in the Pacific had naturally centered on capturing the Home Islands of Japan. This main objective had by the early months of 1942 resulted in a solid strategy by the Army and the Navy. Unlike the war against Germany, where several substantial Allied forces were involved, defeat of the Japanese would have to be almost exclusively conducted by the United States. As such, victory would entail by necessity a unique and new approach that had two goals.

The first was to stop the Japanese expansion in the Pacific. By the start of 1942, the Empire of Japan controlled a good part of China and Burma, all of Malaya (including Singapore), the Dutch East Indies, and Indochina. They had also fortified their mandates, the Mariana Islands, the Carolines, the Marshalls, and the Palaus. Their widespread offensive across the Pacific had seen the fall of Guam, Wake, the Gilberts, the Solomons, and finally, the Philippines. Malaya, French Indochina, and Dutch Borneo had fallen. New Zealand was threatened, and Australia had been bombed several times.

The second goal was, as much as anything, to break the stretched oceanic logistical lines that Japan had established years ago. The Japanese now required these vital sea lanes to both defend their empire and to protect the shipment of goods desperately needed to maintain vital war production.

For the U.S. to ultimately be able to defeat the Japanese by closing in on the homeland, it was determined necessary to commence a full-scale assault throughout the Pacific. The “island hopping strategy,” as it became known, was the only realistic means to array the Allied forces close enough to the final objective of the Japanese mainland.

The Americans had in early May, 1942 scored a marginal naval victory at Coral Sea, thwarting a Japanese invasion of Port Moresby in New Guinea. Then, a month later, they won a decisive victory at Midway, though their efforts to move forward from there that summer were not exactly decisive in nature. A sort of stalemate developed in the Pacific. Neither side could effectively move against the other.

However, the industrial might of a resolute United States then began to come into play: factories were gearing up rapidly, and vast reservoirs of manpower were growing the armed forces at a breathless rate. Hundreds of thousands of men poured into and out of training centers, war matériel for land, sea, and air started to roll off the assembly lines toward the fronts.

Impasse notwithstanding, the Americans were ready to begin their grand strategy for victory. By now, the Americans and the British Commonwealth together were undertaking a maximum effort to neutralize Japanese strongholds and gain logistical support bases with which to expand the Pacific campaign. With the Commonwealth concentrating their efforts in India and Malaysia, the Americans moved westward across the Pacific. At the beginning of August, 1942 they initiated what would become the bitterly fought campaign to take Guadalcanal. Air, land and naval assets on both sides maneuvered and fought for the area. The Allies eventually prevailed, and 1943 saw a shift in momentum as they slowly, inexorably, began to push back. By the summer of 1944, with U.S. war production now in full swing, many of the Central and Southern Pacific island chains had been seized, while in the south, the Army was pushing up New Guinea.

The main American plan of advance had by now evolved into a two-prong thrust across the Pacific. The U.S. Navy under 59-year-old Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, who commanded all Allied naval forces in the Pacific with the title of CinCPac, was to oversee the assault along the northern route across the Central Pacific. The second component was led by the Army, under 64-year-old General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander, Allied Forces, Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) whose objective was to directly assault the enemy through the Southwest Pacific.

By the spring of 1944, the Allied plan seemed to be working. Nimitz’s naval forces in their westward trek had taken the Marshall Islands and were working on the Marianas. The successful implementation behind this advance was a coordinated, two-fisted Navy assault weapon.

The first of this one-two punch combination was a well-developed, massive naval force that centered on a fast carrier task force, a powerful surface attack group of battleships and cruisers, several large escort squadrons, and a virtual armada of support ships that included oilers, escort carriers, and supply vessels. This immense fleet, with all of its technologically updated might, could move across the Pacific at will and take on any naval force that the enemy could mount against it. As such, it posed a grave threat to the Japanese Navy.

The second fist was in the form of a large amphibious task force that could deliver a sturdy, effective landing force onto almost any island in the Pacific. This force had grown over the last two years and now included in its ground forces some five or six divisions, accompanied by a host of amphibious support units.

Working together, these two components made a winning combination. After the naval forces had pounded the target for days from the sea and the air, the Marine landing force, sailing in out of a sea of various types of transports and covered by an array of multi-caliber naval guns that pounded the beachhead areas mercilessly, would storm ashore, forge inland, and secure their objectives.

Naturally, Nimitz’s forces needed adequate support, and the newly created Service Force that had been fashioned by Vice Admiral William L. Calhoun was quite up to the job. This massive, mobile, logistical group had, thanks to the industrial might of the United States, in its ranks vast numbers of supply, support, repair, and medical assets that could sustain both the naval and the amphibious fighting units across thousands of miles of ocean. They were often able to replenish fighting units while underway, able to repair disabled ships in small, setup harbors, and medically treat and evacuate the wounded in an efficient pattern of mobility and efficiency.

After hard fighting and substantial losses through the end of 1942, the Americans had won the air, sea, and land battles of Guadalcanal, and from there, had moved onward to Bougainville, New Georgia, and nearly all of the Solomon Islands. While Nimitz’s fleet pursued an island-hopping battle plan across the Central Pacific, in the south, General MacArthur and his Southwest Pacific Forces surged ahead, moving northwest up New Guinea, which was finally taken in the spring of 1944. Now the general was setting his sights on what for him had been his main objective and the center of his thrust: returning to and triumphantly liberating the Philippines. These were the islands that at the onset of the war, he had so rapidly lost in an embarrassing and unbecoming struggle, and from which he had had to evacuate in disgrace. MacArthur was now keen on getting payback.

The Pacific theater of operations, 1944.

In so many of the War Department’s war-gaming strategies that had been developed over the years, even stretching back to before Pearl Harbor, it had been understood by American senior officers that control of the Philippines would ultimately be essential to any final victory in the Pacific, and as such, the Palaus figured prominently in its seizure.

First of all, the island group lay right in the path of what most plans determined would be one of, if not the Navy’s main line of advancement to the Philippine islands in support of MacArthur to the south. The northernmost island, Babelthuap, had become a moderately sized base and staging area for the Japanese. At the other end, the southernmost island, Peleliu, boasted a large airfield located on a relatively flat plain. The Japanese had used it early on in the war as a refueling stop for aircraft coming from aircraft production plants on the Japanese Home Islands and flying on to the Solomons or New Guinea. If this airfield could be taken, it could be turned into a major airbase from which the Americans could mount a massive bomber offensive against the Japanese forces to the west. Conversely, if it was not taken but instead bypassed, it would be a major communications and logistical threat to the flanks of any coordinated thrust that was undertaken beyond it.

Throughout 1943, securing Peleliu had long been considered by MacArthur to be critical to his success, and as such it remained a milestone in his planning. Thus the Navy had automatically incorporated its seizure into the schedule, and in the fall of 1943, the planning for what was codenamed Operation Stalemate, the capture of the Marianas and the Palaus, was initiated. In this operation, Peleliu and Angaur Island would be assaulted by the First Marine Division and the Army 81st Infantry Division. The large, northern island of Babelthuap would be taken by the Army 27th Infantry Division.

Some nine months later though, the strategic picture had undergone several changes. Commitments to other operations into the Marianas and additional intelligence reports on the Palaus made changes to the operation necessary. The Saipan operation required the 27th Division’s participation, and the invasion of Guam had become bogged down. Thus on July 7, the Navy Pacific High Command revised the Palaus campaign, now retitled the Palau invasion Operation Stalemate II. Planning was overseen by Marine Major General Julian Smith.

By the end of that year though, a strange, competitive inter-service rift in strategic planning had clearly emerged. The U.S. Navy, perhaps taking the Combined Chiefs of Staff strategic guideline given on December 3 of “obtaining bases from which the unconditional surrender of Japan can be forced” perhaps a bit too literally, was pushing to have its northern thrust become the focus of the war effort to take Japan.

The Army in contrast was insisting that the main focus should be to create these bases by taking the Palaus and going into the Philippines, then moving northeastward, up to the island of Formosa, and from there onto mainland China. Although the Chief of Naval Operations himself, Admiral Ernest J. King,* believed that both plans could be undertaken simultaneously, he clearly felt that the northern route would lead to a much quicker and less costly victory than by, as he put it, “battering our way through the Philippines,” which is what the Japanese expected.

By the summer of 1944, with the second front in Europe having been opened and the subsequent ground war in France now at its height, on the other side of the world, the two strategies in the Pacific were openly clashing. The President of the United States and Commander-in Chief, 62-year-old Franklin Delano Roosevelt, found himself vexed by this nagging, distracting problem between these two services.

To make matters on this disagreement worse, the Japanese in May 1944 had started yet another counteroffensive in China, one that now threatened the areas that the U.S. Army had planned to initially use in its strategy. Just after a conference in London of senior British and American generals a week after D-Day, the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff opened up the idea of bypassing the Philippines altogether (and thus follow the Navy’s plan).

The chairman of the joint chiefs of staff, 63-year-old U.S. Army general George C. Marshall, was himself at the time fully concentrated on the huge undertaking in the European theater. He did not want to get the Army embroiled in a large land campaign in the Philippines and China. He was therefore quite open to this proposal, especially since the brunt of the effort would be undertaken by the Navy (including the Marines), which he knew was now a powerhouse out there. MacArthur of course, was incensed by the whole idea of thrusting northeast, arguing several points why such a strategy would infuriate the Filipinos at having been abandoned. Clearly, the matter needed a resolution.

Finally, near the end of July, the president found time to take a break. In Europe, Operation Cobra had seen the American forces breaking out of the Normandy pocket, and Patton starting his lightning dash across France. After being nominated for an unprecedented fourth term as president in the Democratic National Convention in Chicago on July 21, President Roosevelt turned his full attention to the Pacific dilemma. He ordered MacArthur and Nimitz to join him in a strategic summit conference in the Pacific, so that they could coordinate their plans and make a determination on the final strategy could be made once and for all. The orders went out, MacArthur getting his via Admiral Nimitz.

The president knew well that his joint chiefs were split in their theories on how to win the war in the Pacific, so partly for that reason, he deliberately left them in Washington. He was determined to hear both sides directly from MacArthur and Nimitz and then hopefully come up with a solution that would placate both of them. Accompanied by his personal chief of staff, Admiral William D. Leahy, Roosevelt crossed the country and sailed for Hawaii aboard the heavy cruiser USS Baltimore.* On the other side of the Pacific, MacArthur took off from Brisbane, Australia in a B-17 (aptly named “Bataan”) and flew in from the east. By Wednesday afternoon, July 26, 1944, they had all arrived at the main naval base at Pearl Harbor.

The Baltimore reached Pearl Harbor just after 2 p.m., and after entering the harbor entrance, as it passed Fort Kamehaha on the right, the vessel stopped as a launch came out to meet it. The cruiser took aboard Admiral Nimitz and the 14th Naval District commandant, Vice Admiral R.L. Ghormley. The two had come out to personally meet the president. The cruiser got underway again, and as it came into the harbor, the president’s flag flying under the national colors of the main mast, hundreds of sailors stood at attention in dress whites. The Baltimore finally docked at Pier 22-B at 3 p.m., having traveled 2,285 miles from San Diego.

As soon as the gangplank was secured, more senior officers came aboard to greet the president. Among them were Lieutenant General Robert C. Richardson, who was the military governor of Hawaii and senior army officer in the Central Pacific, and Rear Admiral William R. Furlong, the commanding officer of the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard. Right behind them came Ingram M. Stainback, the governor of the Hawaii Territory.

MacArthur, who was well aware of the upcoming presidential election because he had recently himself been a candidate, now seemed convinced that the president was attending this conference in Hawaii mostly for political posturing. MacArthur had in the past had a number of run-ins with Roosevelt and had been keen to run against the established “Roosevelt Dynasty” for the presidency. The general after all was a Medal of Honor winner, as had been his father in World War I,* and now had won a string of victories in the South Pacific the last couple years. A respectable Republican and a war hero, he had been a natural candidate for the office of president, and up until the spring of 1944, several important leaders in the Republican Party had been convinced that the general would be the one to beat Roosevelt in the upcoming election. That included such important figures as newspaper tycoons William Randolph Hearst and Cissy Patterson.

As the campaign began though, MacArthur still remained keen on fulfilling his promised to return to liberate the Philippines, and when New York governor Thomas Dewey edged him out as the Republican frontrunner at the Republican Convention in late June, he returned to his war planning. Still, he continued carrying his distaste for Roosevelt. Now, a couple months later, quite suspicious that the president was just grandstanding by sailing across the Pacific to oversee this conference, the general deliberately made sure that he arrived in Hawaii before the president, but would upstage him by arriving late to meet him. Thus, although his B-17 landed some two hours before the Baltimore docked at 3 p.m., he deliberately put off the meeting. He chose instead to first go to his assigned quarters at Fort Shafter to freshen up.

As he entered the base though, he first went to the quarters of a subordinate there, the military governor of Hawaii and senior army officer in the Central Pacific, Lieutenant General Robert C. Richardson. The general though was not in, having chosen to go to the piers to meet the president after his cruiser had docked. There at Richardson’s quarters, MacArthur took his time chatting with some old army friends before taking a shower. Finally he departed in a large, open army limousine. MacArthur rode alone in the back, wearing a styled khaki-colored leather jacket, a crushed army officer’s cap, and his trademark dark sunglasses. He and his motorcycle escort arrived at the dock with elaborate fanfare, which included sirens, whistles, and, of course, applause and cheers. His limo pulled up and MacArthur got out, stopping for two ovations before bounding up the gangplank and boarding the heavy cruiser at 3:45 p.m.

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet (CinCPac). Seen here talking to General Rupertus.

General Douglas MacArthur, Commander, Southwest Pacific Area.

Admiral Leahy met him on deck and, with a smile, asked, “Douglas, why don’t you wear the right clothes when you come to see us?”

Grimacing, MacArthur replied, “Well, you haven’t been where I came from, and it’s cold up there in the sky.”

After a short meeting with the president and Admiral Nimitz (who was dressed as protocol required, in his starched regulation dress whites), they went on deck at 4:15 to do a photoshoot for the media photographers. They then each departed the ship around 4:30 for the night,* the president to his assigned quarters at a lavish three-story Waikiki estate, just off Diamond Head on Kalaukau Avenue, overlooking the beach.* Admiral Nimitz returned to his quarters at 37 Makalapa Point in Pearl Harbor, and General MacArthur rode back to Fort Shafter. There he complained that evening to General Richardson about having to leave his headquarters for a photoshoot, especially when he had received an invitation from the president that evening to go on another publicity tour the next day.

The following morning, the general and the admiral met the president at his villa, and at 10:45 a.m., the three of them, accompanied by an entourage of various senior officers, began the day touring facilities on Oahu. They were accompanied by the media (MacArthur, on his way to see the president, had been quoted as being upset over being forced to leave his command for this “picture-taking junket.”) With MacArthur sitting in the back between the president on the right and Nimitz on the left, they toured several military bases in a luxurious, bright-red 1941 Packard, owned by the Honolulu fire chief (Roosevelt later chuckled when he found out that only one other such vehicle was in Hawaii, and it was owned by the madam of Honolulu’s largest house of ill repute; she had begged that they use her car, but it would have easily been recognized, and that would never do). Since the military had evoked a strict news blackout on this trip and the conference, few photos were taken, and there were absolutely no news reports sent. The conversation in the Packard mostly centered on politics and the upcoming presidential election in November.

The tour included visits to the Marine Corps air station at Ewa, the Navy ammunition depot at Lualualei, Schofield Barracks, Wheeler Field and the Post hospital in Honolulu, the Seabee camp at Moanalua Ridge, and finally the Marine Corps training center at Camp Catlin.

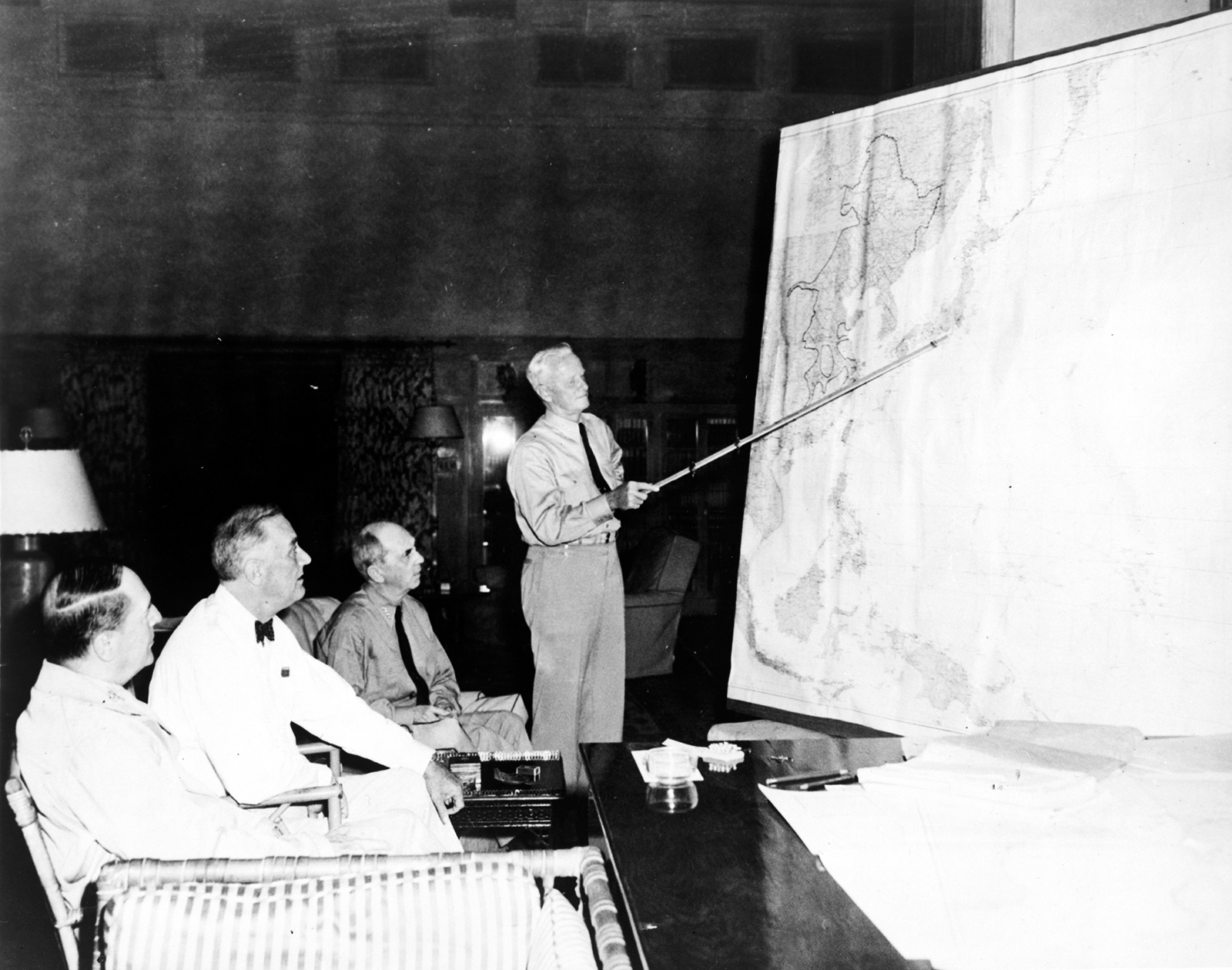

At 4:20, along with twenty-some senior officers and advisors, the VIPs were taken back to the president’s quarters on Kalaukau Avenue. There, after cocktails they began a sumptuous prime-rib dinner at 7:30 p.m. About an hour later, the meeting began in an adjoining conference room. In addition to President Roosevelt was the senior Navy contingency, which included Admiral Leahy, Admiral Nimitz, and a number of his senior advisors. Representing the Army was just General MacArthur.

The president was sitting, wearing a white shirt with a dark bowtie with white spots, his glasses in their leather case in his shirt pocket. He began the meeting by taking a drafting T-square and, using it as a pointer, he turned his wheelchair around, to face a large map of the Pacific that had been mounted on board. Pointing to somewhere near the Philippine island of Mindanao, he then looked at General MacArthur on his right, and opened the conference by saying, “Well Douglas, where do we go from here?”

Returning to the Philippines had been a haunting obsession with MacArthur for almost two and a half years, ever since his combined forces had been defeated by the Japanese in December of 1941 in a humiliatingly swift campaign. Ordered to escape to Australia, he barely made it out, leaving in the dead of night of March 12 with an escort group of four PT boats. When he had finally arrived in Melbourne on March 21, he had made his stubbornly resolute promise statement to the islanders that “I came through and I shall return.” That guarantee, now a fixation, had been the foremost objective in his strategy since then.

So now at this conference, MacArthur, wearing a light army jacket, looked defiantly at the commander-in-chief and replied, “Mindanao, Mr. President. Then Leyte and Luzon.”

The president then turned to Nimitz and asked him what he thought. The admiral, already standing, took the T-square from the president and began his assessment. Pointing to the Philippines, he started by arguing not only against an invasion of the Palaus, but against an invasion of the Philippine islands as well, which, by extension, the Peleliu operation was designed to support. He spoke somewhat stiffly in a soft tone, and his remarks were simple and to the point.

Nimitz contended that they instead should concentrate on an alternate, two-prong drive to Japan. The southern prong would bypass a probably costly and lengthy invasion of the Philippines. Rather, they should concentrate on a drive to take Formosa (Taiwan), Iwo Jima, and Okinawa, in preparation for a direct assault on the Japanese main islands. The right-hand prong would be to attack them through an intensive strategic bombing campaign by moving up the Bonin Islands—an archipelago of some 30 islands 500–600 miles south of Japan—and securing them.

Then it was MacArthur’s turn. He stood up, took the pointer from Admiral Nimitz, and began by countering that the main thrust instead should be through the Philippines. His arguments were not so much military as they were political and ethical.

Strategic conference in Hawaii, evening, July 26, 1944. Admiral Nimitz (standing) outlines to (from left) General MacArthur, President Roosevelt, and Admiral Leahy the Navy’s strategy to defeat Japan by taking the northern route. Unlike MacArthur, Nimitz recommended bypassing the Philippines (and thus, Peleliu) to drive straight to the Japanese Home Islands. The president ultimately rejected this plan and sided with the general. (U.S. Navy photo)

MacArthur tried to pressure the president into favoring his plan by reminding him of his iconic “I shall return” promise to the Philippine people back in March of 1942. His argument focused on the political implications (and perhaps subtly their ramifications in this an election year) of how fulfilling that pledge would benefit U.S.–Filipino relations. More damaging, MacArthur pointed out, would be the negative message to the rest of the Central Pacific. “Promises MUST be kept,” he said pointedly, and to underscore his argument for maximum effect, his next sentences included the words “shame,” “ethical,” “unethical,” and “virtue” several times.

The United States had after all, undergone a number of political struggles in the Philippines as the island state over the years at various times had tried to gain independence. The Filipinos, he argued, who in many respects looked upon America as their big brother or even their mother country, felt like they had been betrayed in early 1942. The Americans had blundered terribly and had failed them with not only its defective military strategy, but also (to them) its feckless lack of determination to aggressively defend their islands

If the Americans did not at this stage even try to liberate the Philippines, but rather blockaded and bypassed them, moving onward toward Japan, they would in essence allow the cruel Japanese occupation to continue persecuting the Filipinos, who in turn would be infuriated. Supplies on the islands, having already been short for months because of the American naval blockade, would become far more acute. In response, the Japanese would simply resort to taking more from the Filipinos, and, in doing so, subject them to further suffering, barbaric cruelty, and death. The islanders would feel betrayed and abandoned yet a second time. For the Americans to turn their backs on them now would no doubt give rise to a bitter sense of betrayal that would spark a new determination to break free of what would be seen as uncaring, American oppression. To them, this would be an outrage, one they would probably never forgive. It would be a stain on American honor that would come back to haunt them if (or more likely, when) the Philippines became their own nation sometime after the war. To worsen the effect, this unfaithful act of not fulfilling that pledge would have a negative impact in the eyes of other Far Eastern nations as well.

MacArthur concluded that therefore, the drive to take the Philippines had to be paramount. He then went into additional details of his strategy. To ensure the maximum chance of success in the campaign, as an integral part of his plan, they first needed to take Peleliu to cover his right flank, to provide a major airfield to support his forces, and to allow him to make his main assault unhindered. The Japanese airfields could be taken out from Mindanao, and as soon as U.S. airfields could be set up on Leyte or Mindoro, MacArthur could land at Lingayen Gulf and move to take Manila in a little over a month.

Here the president commented that the Philippines campaign might be too costly to undertake in terms of men and matériel. “To take Luzon would demand heavier losses than we can stand. It seems to me we MUST bypass it.”

MacArthur assured him that their losses would not be heavy; at least, no more than they had been in the past. He added, “The days of the frontal attack are over. Modern infantry weapons are too deadly, and direct assault is no longer feasible.” He paused and added, perhaps in an oblique inference to Nimitz’s heavy losses in the Marianas, “Only mediocre commanders still use it. Your good commanders do not turn in heavy losses.” In fact, he continued, taking Formosa would probably be more costly in losses. A landing there would be over a long supply line, and the troops coming ashore would not get any help from the local civilians, since Formosa had been under Japanese rule for half a century. MacArthur continued arguing the military positives of taking the Philippines. Unlike with Formosa, the Filipinos would doggedly support the American landings with strong guerrilla actions. Besides, he concluded, bypassing Luzon, like the strongholds at Rabaul and Wewak, was impractical because it was just too big a land mass—Leahy apparently concurred—and even if they could, the large Japanese forces based there would wreak havoc upon the left flank of any American advances to the north of them.

Although Nimitz’s line of reasoning was itself solid, he had three factors that were working against him. First, as competent a leader as he was, Nimitz was for the most part not much of a dynamic speaker. Rather, he spoke in a soft tone, comparatively not nearly an eloquent a spokesman as the grandiloquent general. A subtle factor, granted; still, the arguments that he presented were not as persuading. Second, the idea of bypassing the Philippines (and thus, Peleliu) was actually the firm recommendation of his superior, Admiral Ernest King. Nimitz was just echoing those ideas. In fact, MacArthur later concurred with this statement, writing that Nimitz had not really agreed with King. Admiral Halsey’s writings in 1947 also confirmed that statement. At the time, besides Nimitz, King’s strategy was in reality questioned by a number of other senior admirals, among them Raymond Spruance, the hero of the battle of Midway.

The third factor working against Nimitz though, perhaps the strongest, was that he really had no viable argument, military or political, to counter MacArthur’s heavily laid concerns about bypassing the Filipinos, and all that that would imply.

The high-level meeting went on for almost three hours until finally, around 10:30 p.m., the president, tired from the day’s activities (and no doubt, as well as from MacArthur’s arguments), declared, “Let’s adjourn for now and get a good night’s sleep.” He paused and added, “We’ll resume tomorrow morning at 10:30 for a final review, and then I’ll give you my answer.”

General MacArthur, according to his writings after the war, managed to get the president alone for some ten minutes after the meeting, just before Roosevelt had a chance to retire for the night. (One source—John Prados—claims that this occurred the next day, just before MacArthur departed for his flight.) MacArthur recapped one last time his ominous warning of going around the Philippines, now addressing the political repercussions of not going with his plan. He again brought up the upcoming general election in November: “I daresay that the American people would be so aroused that they would register most complete resentment against you at the polls this fall.”

Roosevelt already had enough worries about defeating Thomas Dewey, who he pointed out was not only a well-liked Republican presidential candidate, but also widely popular as the governor of New York. Perhaps unspoken but nevertheless probably in the back of Roosevelt’s mind was the fact that MacArthur himself had earlier been a Republican contender.

Just before going to bed, Roosevelt had a chat with his physician, Vice Admiral Ross McIntire. Then he took a couple aspirin and turned in.

The next morning, July 28, MacArthur and Nimitz arrived at the president’s quarters at 10:15 a.m., and the conference started again, 15 minutes later as planned. Roosevelt, having pondered and then slept on the general’s warnings, had already made up his mind on which strategy he was going to decide upon. Still, he politely listened for an hour and a half as both sides gave their final arguments, each reiterating the same contentions they had made the evening before.

MacArthur was on some sort of moral crusade, perhaps using the moral high ground because he had been awarded his Medal of Honor just two years ago for his defense of the Philippines. For whatever reasons, he was continuing that angle. At one point he said, “If the Philippines are left behind in the backwash of war, the Japanese army can live off the land, and will slaughter in revenge, thousands of prisoners, including women and children.”

In the end, MacArthur was the more convincing. Roosevelt finally held up his hands for the discussion to end. He looked at his senior officers and told them that he was approving MacArthur’s plan. They would go with an invasion of the Philippines—and thus, Peleliu. There was no visible reaction from either Nimitz or MacArthur. Admiral Nimitz, hearing the president’s decision, accepted it with good grace, and told them that he would begin planning to support the campaign. A bit later, the president took MacArthur aside and told him with a smile, “Well Douglas, you win. But I’m going to have a helluva time over this with that old bear, Ernie King!”

The conference then continued as MacArthur voiced his concerns that the British, now that the naval war in Europe had been won, were plotting to expand their role in the Pacific and set up their own command in the Far East, which to him, would weaken U.S. influence across Asia.

The meeting broke up around noon, and as lunch was being prepared there at the president’s quarters, a couple newspaper photographers were called in for a quick photoshoot. Afterwards, MacArthur, having won the strategic argument and perhaps having irritated the president for any number of reasons, stated that he was not staying to eat. His excuse to the president was that he had to get back to his headquarters immediately, grumbling, that he had “to resume fighting the war,” and that his aircraft was already warming up at Hickam Field.

Nimitz stayed, and after MacArthur departed, he and the president had a sumptuous lunch, again heavily covered by the media. Nimitz then left for his quarters, and the president, accompanied by Admiral Leahy, General Richardson, and Admiral Ghormley, once again rode around Oahu, touring the island and the various units stationed there. He then returned to his quarters, had another lavish dinner (which included a 17-piece band for entertainment), and then went to bed around 10 p.m.

He continued touring Oahu on the 29th, including visits to the Army General Hospital, the Naval Air Station in Honolulu, Hickham Field again, and then the submarine base.

Then after a lunch, with about three dozen senior naval officers at Admiral Nimitz’s quarters and another tour of the island, the president held a grand press briefing before his six-car motorcade drove to the pier. The president had a final chat with Nimitz, before his wheelchair was rolled up the gangplank to the USS Baltimore, boarding at about 7 p.m. The vessel departed Pearl Harbor a half hour later, headed for Adak Alaska in the Aleutians.*

Several historians have argued that Roosevelt decided to go with MacArthur’s plan because, in the long run, MacArthur was right: it politically made sense. Advancing through the Philippines delivered the additional gift of placating MacArthur, who the president knew, could really give him all sorts of endless headaches back home. The general no doubt would not only have raised hell with both the conservatives who had supported him in his run for the White House, and with the Democrats supporting the president. The general would also have bemoaned the decision to other senior Army commanders and to the Department of War, complaining that this was just another effort by Roosevelt and Nimitz to allow the Navy to command the war in the Pacific and to glorify that service as being the foremost.

Some have criticized that the entire Philippine campaign that MacArthur had pushed so hard for was based upon his own egotistical obsession to fulfill his personal promise to the Filipino people. In retrospect, although taking the Philippines made more strategic sense than Formosa, MacArthur’s campaign to clear every corner of the islands of its Japanese occupiers seemed to some later historians wasteful in time and resources.

With the conference ended, Nimitz resigned himself to the president’s decision. After cocktails and dinner with his disappointed staff at his quarters that night, the admiral told his them that he had expected the decision, and that as far as he was concerned, they would carry it out in good spirit. He told them to fully cooperate with the field units to make it happen. Perhaps as an afterthought, a Navy captain later remarked to a Newsweek correspondent that Nimitz ordered a message be sent to the First Marine Division’s headquarters, instructing that Operation Stalemate would proceed as planned.

True to his word, Nimitz began his strategic planning by first concentrating on the Peleliu operation. In his early developmental stages, Nimitz wrote that taking Peleliu would, “remove from MacArthur’s right flank in this progress to the Southern Philippines, a definite threat of attack; second, secure for our forces a base from which to support MacArthur’s operations.”* Taking the Palaus would cover MacArthur’s right flank as he moved on the Philippines, as well as outflanking the still formidable Japanese-held strategic port of Truk, which the Americans had decided to bypass.

The original tentative date that had been set for the Palaus operation was December 31, 1944. It had been moved up to September 8 because the U.S. westward advance had proved faster than expected. On July 7, it was concluded that the operation would take place on September 15th.

*Mandate is a term that refers to the 11 territories or protectorates surrendered by Germany and the Ottoman Empire at the end of World War I. The process was created by the League of Nations through Article 22 of its charter, whereby a territory was assigned to an Allied power (the “Mandatory”), ostensibly until the territory could govern itself. Nearly all mandates remained under the control of their Mandatory until after World War II.

*King actually wore two hats: not only was he Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), but he also carried the lesser title of Commander-in-Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH), which included all U.S. naval surface forces in the Atlantic and the Pacific, but did not include the Asiatic Fleet, nor naval land forces. The COMINCH billet was abolished in October, 1945 by King, who by then had been promoted to fleet admiral.

*USS Baltimore (CA-68, Capt. Walter C. Calhoun, commanding) was a heavy cruiser, the first of her class, commissioned in mid-April, 1943. At 13,600 tons, she was 674 feet long, 71 feet wide, and had a draft of 27 feet. With a crew of 1,200, she could make 33 knots. She was armed with nine 8-inch guns, 12 5-inch guns, 12 quad 40mm AA guns, and 24 20mm AA guns. In the course of the war, she earned nine battle stars.

*General Arthur MacArthur Jr., as a lieutenant, was awarded America’s top medal in 1890 for combat in the Civil War during the Chattanooga Campaign of 1863. As adjutant of the 24th Wisconsin, carrying the regimental colors, he charged up Missionary Ridge on November 25, 1863 at a critical point in the battle, yelling “On Wisconsin!” Arthur went on to fight in the Indian Wars, the Spanish-American War, and the Philippine-American War, eventually attaining the rank of lieutenant general. Douglas received his in 1942 for (today controversial to historians) defense of the Philippine Islands. This unique phenomenon of both father and son earning the Medal of Honor, the first time in history, would not be repeated until Theodore Roosevelt Jr. was so awarded for his actions in Normandy, following in the footsteps of his father, President Theodore Roosevelt, who earned the medal riding up San Juan Hill in the Spanish-American War (the president though, was only awarded the medal posthumously in 2001).

* Interestingly, the only other time the president had ever visited Oahu was July 26, 1934, aboard the heavy cruiser USS Houston (CA 30). Just a year and a half into his presidency, having left Annapolis, Maryland on July 1, the ship pulled into Honolulu harbor on July 26, exactly ten years to the day before this conference.

*The estate had been owned by millionaire businessman Chris Holmes, heir to the Fleischmann yeast estate, a staunch Democrat, and owner of a major corporation on the islands, the Hawaiian Tuna Packers. When he died in February, 1944, the mansion, along with the rest of his estate, went into a trust, managed by the Hawaiian Trust Company. After the Roosevelt visit, to help the war eff ort, bunk beds were put into the upstairs rooms, and the mansion became a recreation center, first for Navy pilots, and later in the war, for other servicemen. The estate was purchased by the City of Honolulu in 1946 and turned into a popular nightclub, The Queen’s Surf.

*Most accounts of this conference state or imply that Roosevelt’s stay in Hawaii was just from July 26 to July 27, that the conference began the evening of the 26th, and that Roosevelt left Hawaii the next day. Actually, as accounted here, the president arrived the afternoon of July 26, the conference did not begin until the evening of the 27th, and the president did not depart Pearl Harbor until the evening of July 29.

*From a letter written by Admiral Nimitz to Philip A. Crowl dd. October 5, 1949.