Old Friends

A couple decades later, after having retired from the convenience store, I started trying to find out what had happened to my war buddies. Some I knew where they were, but many I did not.

Melvin “Waddy” Getz served in Panama during the war and never saw any action. He got married to Betty on July 24, 1950 and had three daughters: Margie, Jeanette, and Laura. Waddy’s brother Danny, served with Merrill’s Marauders in the CBI1 and was later sent back to the United States, diagnosed with battle fatigue—PTSD. He finally recovered enough to work in a factory for a few years. He later bought a 250-acre backwoods ranch north of Cambridge, near Londonderry. Waddy’s younger brother Warren (“Boysee”) joined the navy after the war began and got married. Some 50 years after that, Boysee and his wife decided to renew their vows at Lake Ann. Waddy came to the ceremony. It was an unusually hot day, and near the lake, the two brothers sat down on a wall to rest. They were talking as Boysee, uncomfortably hot, collapsed to the ground from a heart attack and died right there. Waddy passed away on Monday, January 26, 2009 in Cambridge.

Jefferson Davis (“Jeff”) Watson, Jr., who I had gone on several liberties with in Davisville, Rhode Island, had joined the Marine Raiders, as a part of C Company, 4th Raider Battalion.2 He was killed in action on July 20, 1943 during the battle at Bairoko in New Georgia. His body was never recovered. He does not have a grave there on the island, but he does have a vase (but no actual body) within a mausoleum in Manila’s big national cemetery.

After he had been shot up on Peleliu and evacuated, I never saw my buddy Jim Olivera again. Last I heard, he was living in Fall River, Massachusetts.

After Parris Island, I never bumped into John Siler again, the guy we had coerced into joining with up back in August 1941. I did find out that he had landed on Iwo Jima.

I never met Richard Tomkins again either, the guy who had introduced me to Phyllis Carpenter in the fall of 1939. All I ever heard of him was that he had been shot up in the Gilberts.

Bob Johnson, who had been one of our platoon’s communicators, after the war went back to Godfrey, Illinois3 and became a barge inspector. He came to visit me a couple times just after I returned, and we had some real good “liberties” in Akron. I saw him occasionally after that whenever I traveled west. On my way to California, I would stop and visit him in Godfrey.

Carl Jenkins went back to Cleveland. I, years later, went to his wedding.

One of our corpsman, Al (Alfonso) Romero, became a prominent federal judge in San José California. He lives with his wife Lucy in Aptos, just east of Santa Cruz.

Joe Rzasa survived the war and eventually moved from Massachusetts, New Hampshire to Laconia, Florida, and became a machinist. He was married for some 60 years to Alice before he died on October 22, 2005.

I never did see Lt. James Haggerty again after he left me on Okinawa at the end of June. A few decades after the war, I met W. A. Young, the officer who had fired the rockets on that LCI at Peleliu. As a lieutenant, he had come into our mortar platoon for a week or so on Okinawa. When he was with I Company, he had been shot in the back. We assumed it had been by the Japs, although he had been a caustic sort of fellow, kind of nasty to everybody, so who knows? Anyway, I met him many years later, and he claimed that he had run into Haggerty in New York right after the end of the war, somewhere around the end of August. That was the only instance that I heard of anyone ever being in contact with the lieutenant. Many years later, Bill Mikel told me that Haggerty had passed away not long after he had returned to the States. According to Bill, he had gone into hospital for a minor operation and he had died. Apparently, so had Lt. Joe Murphy. I never found out anything else about him.

Clarence G. Keele, one of our platoon’s ammo carriers, after the war moved to Detroit and went into law enforcement, like his father, who was a sheriff in Texas. Clarence himself later became a Texas highway patrolman, and eventually landed a policing job with General Motors. He made a career with GM, and years later, became the head of their Investigative Division. I remember that big Texan S.O.B. with these huge hands. He was a quiet guy, not very chummy with many, but he and I always did get along, and he always defended me. When he died in 2007 in Grosse Point, Michigan, a lot of GM big shots attended his funeral. They presented his casket with a Marine Corps white barracks cap, and, strange as it seems, that was the first time anyone was aware of his service in the Marines.

Bob Sprangle, who had been my calm phone man on Okinawa and had followed me along the line, survived the war and went back to his wife and kids in Toledo. In 1947, I found out that he was running a grocery store that he had inherited from his father. I once went up to visit him, and we had a nice couple of days. A little after that, he died.

Albert J. (“Al”) Cook, who had been in charge of the platoon’s communications, ended up in I Company. He survived the war, went back home to Erie, Pennsylvania, married a great gal named Mary Ann, and became a banker. I saw him occasionally when we went hunting together out of his cabin, and also when he attended a number of our reunions. He wrote a short autobiography in 2009, and died five years later.

Albert William (“Bill”) Mikel, the mortar gunner who had joined us just before Peleliu, lived to be old like me. Like a number of survivors after the war, Bill wrote a few articles about our experiences on Peleliu. Before he went off to war, he had already acquired a wife and kids, and so he wrote home almost every day, and in doing so, had kept a secret diary. Now Bill had a good eye for detail and an accurate memory, so he used his notes and memory to write a few stories of our encounters. One was about Lt. Haggerty on Peleliu in The Old Breed July 2015 issue, entitled, “A Salute to Lt. Haggerty.”

Norman L. Leishman, the No. 4 mortar assistant, returned home to Santa Monica, California. His family had considerable influence in the area. His father, Lathrop Leishman, was a VIP with the Rose Bowl in Pasadena.4 His father brought Norman into the family construction business, where he pursued a successful career.

Russell Diefenbach, who had been the loader for the No. 3 mortar in our platoon on Peleliu, and later on Okinawa our No. 3 Gunner, survived wounds that he received in each campaign. In his later years, he wrote a self-published book on his wartime experiences, and stayed in his hometown of Aurora, Illinois.

Joe Miceli, who had been a key part of the platoon’s communications team, returned to Cambridge Massachusetts and became a police officer for the City of Cambridge. For many years, Joe was a fervent part of our reunions. He passed away on March 19, 2016.

Joe LaCoy, K Company’s 60mm mortar chief, survived the war and went back to Alabama. I get a Christmas card from him every year. I heard that a few years ago, the old buzzard skydived out of an airplane.

After Cape Gloucester, I never heard anything about those crazy Woodring brothers until after the war. I was working down at the Silver Dollar Bar at Broad and High Street in Columbus at the time, and I was on my way in to work. Starting to walk into revolving door of the Gray Drug Store on the corner, I saw what seemed like a familiar face coming out. Stunned, I realized it was one of the Woodring brothers. He recognized me, and after a couple hearty greetings, we talked briefly. He was the twin who had been hit by that tree branch that stormy night back at Cape Gloucester in December 1943. Today, he had come down from his home in Paulding, Ohio to go to the VA facility for a health problem—no doubt related to that injury from that tree limb. Me, I was so happy to see him, I tactfully decided not to bring up the five dollars that he (or his brother) still owed me. And funny, all these years, not only could I not tell them apart, but I could never remember their names.

Lt. Curtis Beall after the war for a few years was some sort of government agent. During the rest of his life, he owned a Christmas tree farm and for while he raised and sold catfish.5 For years afterward though, whenever I had occasion to visit him, he would tell his family with pride that I was the guy that saved his life, and his son Al grew up with that. After Curtis died in 2013, Al again thanked me for saving his life.

Twenty-year-old Raymond Gilder Kelley, who had been on the No. 4 mortar crew, went back to his job with the railroad in Elderidge, Alabama. One day, working in the railroad yard, he was hit by a train. Even though it had been slow moving, it messed him up. R.G. was a quiet sort of fellow. He stood about six four although he was always hunched over. His wife’s family had money, and they ended up owning the fire department and two old grocery stores.

I remember taking a camper down there around 1990 to visit him. His wife Helen was a schoolteacher, but worked part-time in the town post office in the summer. When she heard me telling someone my name, she came out right away.

“Peto?” she exclaimed. “I know HIM!”

I grinned and said, “Well, I’m it.”

A crowd gathered around us as she gave me these big hugs. She had heard so much about me that she thought she knew me. I guess she expected me to be 10 feet tall or something from Guilder’s stories. Kelley died November 10, 1995 and was buried in the town’s ten-acre cemetery that his family owned.

After John Skoglie and I did our wild stint in San Diego in November 1945, I never saw him again for some 60 years. In 2005, I drove out to Burbank, California to visit my mom and my sister. Afterwards, instead of heading home, I decided to try and find Skoglie. His father had been a northern California miner, which explained why John had been fascinated with mineral exploration and ores all his life. I knew that he had returned there, but where, I did not know.

I drove north up to the backwater areas of northern California where supposedly John lived. No one knew of him, and his name was not in any of the phonebooks. I finally ended up in this little town where Al Cook had found some report that a guy named John Skoglie had committed suicide. I hoped that it was not my friend, but I had to find out. I walked into the little police station and asked the lady at the desk if they had any information on a John D. Skoglie. She checked her records and confirmed that there was a report of a John Skoglie that had committed suicide. From what she told me though, this fellow was much younger and could possibly have been my buddy’s son. She printed out a copy of that record for a buck and I thanked her. Using the information on the sheet, I made a few phone calls, but again, no luck. No one knew anything.

Depressed, I finally drove back to Ohio. But I was not going to give up. I made a couple more calls to some other names on the report. Finally, I struck oil. One lady told me that she knew John, and that he now lived in a small crossroads town called Imlay in Nevada.6 She gave me his phone number, and I finally was able to get a hold of him. Excited, I told John that I would like to get Al Cook and drive out to see him soon. Skoglie loved the idea, so we started to make plans. We drove across the country, through Colorado, to Oregon, and picked up another one of our old platoon buddies, Ernie Huxel, who lived in “The Dalles.”7 Then we all left in Huxel’s car headed south, to go down about 500 miles to Imlay, Nevada.

Ernie told us that he had gone into construction running a bulldozer. As he put it, “Hell, anyone can do that. But not many guys can maintain an even grade like I do.”

Even though Ernie drove a slow dozer—or maybe because of that—one of his favorite hobbies became auto racing. He owned a couple cars that he had bought and souped up. So as you can imagine, he drove fast and perhaps to some people, somewhat recklessly.

Al Cook was one of those folks, now nervously sitting in the front on the passenger side. Now let me explain that Al was a strange sort of fellow. He had joined the Marines around the same time as I had, but he had been assigned to the First Marine Division in mid-1942, and as such, had been on Guadalcanal. On Peleliu, he had been the section leader of our mortar platoon’s communications group, and like his comrades, after Peleliu, he had been rotated back to the States.

I think that was just as well. Albert was a good Marine, all right. But it seemed to me that he didn’t have the temperament to be a gung ho combat soldier. Since he had been in charge of wires and field phones and such, his job had never been to mix it up with the Japs and kick ass. He had just been in charge of the linemen.

Another thing about Al I found downright spooky. He had a sort of tunnel vision.

He didn’t use his peripheral vision very much, not like me. Al was the sort to always look forward. I remember one time on the way out to get Huxel when I was driving, I had spotted a deer off to the right, on his side. “Hey, did you see that deer?” I asked him.

Without batting an eye, looking straight ahead, he had said, “No.” He didn’t even turn his head to talk to me, much less to view the scenery. It was peculiar as hell.

Huxel was in a carefree mood, and his driving showed it, and while comparatively tame, Al in the front passenger seat was getting nervous. Watching him sometimes shake his head, I imagined Al thinking, “Man, I survived all them damn Japs and now I’m going to get killed with this maniac driving.” I don’t know why, but that thought amused the hell out of me. At one point Al said, “Ernie, you’re gonna get a cop on our tail.” But Huxel just smiled and drove on as if he wanted to break some sort of speed record.

We got into Nevada. Every once in a while, Huxel would approach a curve that Al figured deserved a little more respect, and as Huxel veered the car around the curve, the tires growling over the road, Al would sometimes thump his left foot onto the car’s floor in a vain attempt to find his own brake pedal. This went on for a number of curves.

Finally, Ernie screeched the car to a halt and turned to Cook. “Now look Al, I’m doing the damn driving, so let me do the damn braking.”

I don’t think I ever laughed so much in my life.

And that’s how we continued on our way to Skoglie’s, with Huxel racing along, and wide-eyed Al staring at the road ahead, sometimes gripping the door handle.

We drove through swamps, with thick groves of tules8 round them. They looked like cattails, but round instead of flat. Huxel’s little car had no air conditioning, so we were all sweating.

Finally Huxel growled, “It’s hotter than hell. Roll all the windows down. I’m gonna air this damn thing out.”

We rolled our windows down and he took off down the road like a bat out of hell. I thought old Al was going to have a heart attack right there, with Huxel driving like crazy to keep the dust from whipping into the car.

We reached John’s ranch in Nevada and he came running out in his blue bib overalls. I could tell by the big grin on his face that he was happy to see us. He had always been a quiet sort of guy, but he had always been ready to go on an adventure with me. Now he beamed from ear to ear, ecstatic to see some old Marine buddies.

As we approached, John pointed to his chest and said proudly, “I was one of Peto’s raiders,” referring to the many night excursions we had taken in the Pacific islands. Yes, Skoglie too had always been an explorer. So many times we had gone off at night just to see what we could find, and what mischief we could get up to. It looked like he had continued to be the explorer, now out West. He sure as hell dressed the part. With his big overalls and this huge moustache and beard, he looked just like a gold miner. All he needed was a mule to drag along.

We talked a bit, and then he gave us a tour of his ranch. That evening, he had an indoor barbecue and cooked us these huge, juicy steaks. We stayed a couple of days at his ranch and had a great time before we started heading back in a heavy snowstorm. That was the last and only time I ever saw John Skoglie again. He died at the age of 83.9

There was one good friend that had served alongside my division in the war. A funny thing though, I did not actually meet him until fifty years later. His name was Joe Dodge, and he lived not far from me in Marysville, Ohio. Joe had fought with MAG-1210 in the Pacific as a flamethrower operator, and he saw action on Cape Gloucester and later on Peleliu. It was there that he came down with an infection of some sort, and Joe spent the next six months after the campaign recuperating. When he was well enough, they sent him home to the States. It was there that he found out from his family doctor that he had contracted a case of acute jaundice.

I met Joe when I joined the Marine Corps League in the summer of 1995. Joe was two years younger than me. We hit it off right away. This guy really lived at the foot of the cross, so to speak, and I really liked him. After the war, Joe worked for 20 years at the Scott’s Fertilizer plant, before he turned to farming. He and Karen bought this big farm right next to his aunt’s farm, located just outside of New California, Ohio, which is about halfway between Dublin, Ohio and Marysville. There were plenty of woods, which I found out, were great for all sorts of hunting. So Joe and I would often go out for hours in their woods, hunting for all sorts of critters: deer, coyote, groundhog, squirrel and the like. My great hunting buddy Joe passed away in the fall of 2013.11

Every now and then, we living survivors of our mortar platoon would have reunions. There was quite a showing for the first one, with 41 people attending. Of course, that included all those guys that had served in the platoon at various times over five years, including some 30 replacements just before the division had shipped off to China in 1945. So some of these guys I did not even know. Like for instance, Karl Tangeman, who I found nice to talk to and had a good memory. For many years, he was the chaplain at our platoon’s reunions. After the war he became a Baptist minister, so we figured he knew what he was doing in the prayer department. I had never had a chance to know him, because he was gone from the platoon before I was assigned to it.12

We also had our share of personality conflicts, a couple of which probably had their origins in the Pacific. A few of these guys had idiosyncrasies in their personalities, and so sometimes a couple of us would have to step in and play the diplomat. And as we got older, our strange behaviors intensified. Howard Quarty, for instance, had always had a bit of a mean streak in him, and it would come out whenever he drank. Joe Miceli had been a cop for 25 years, so we assigned him the job of watching Quarty whenever he got drunk.

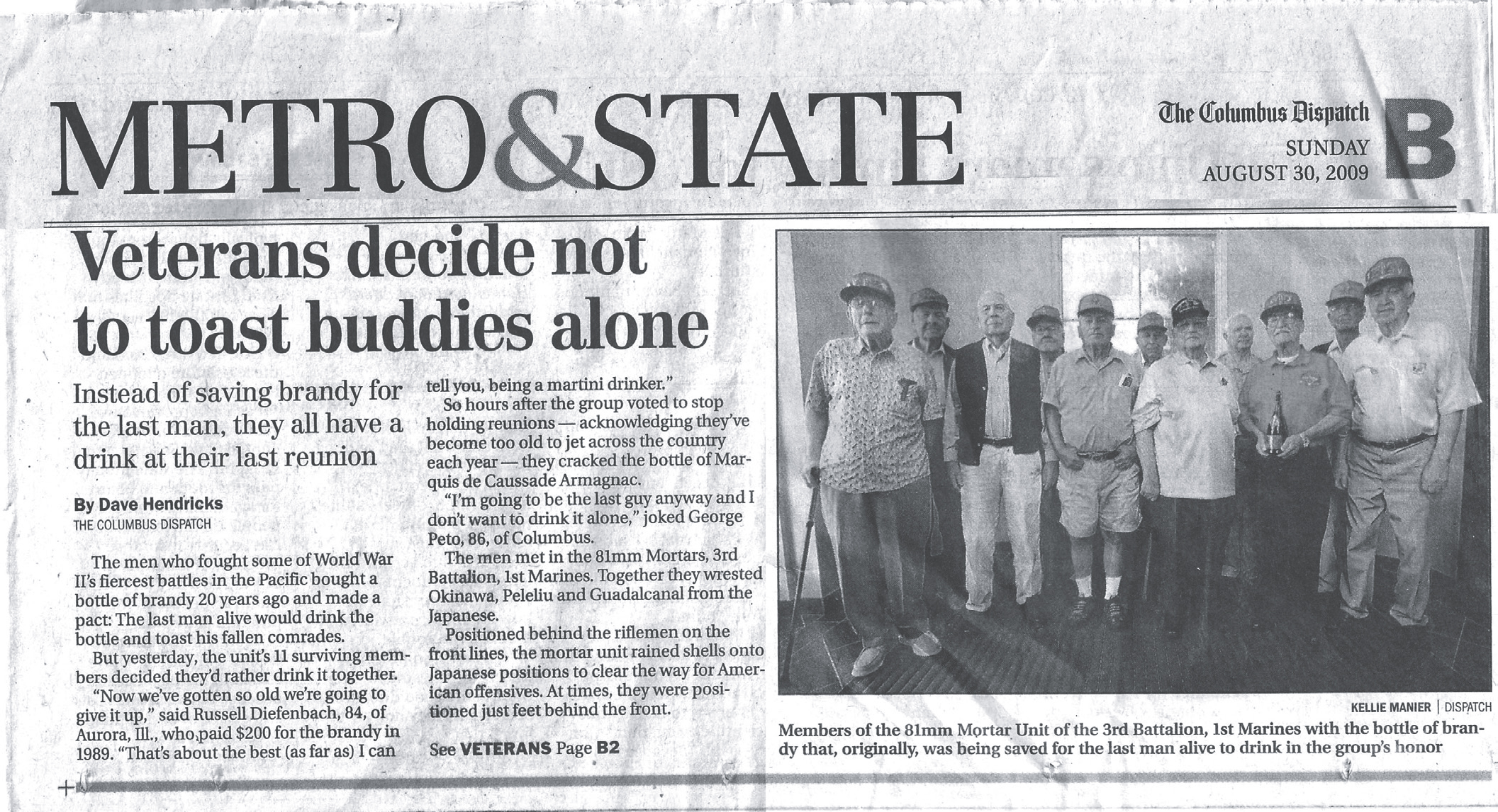

Last Man Reunion for George’s Mortar Platoon, 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines. Columbus Dispatch (August 30, 2009).

In 1989, we had our first big reunion in Columbus, at the Harley Hotel on Route 161. In the next years, we had more in other big cities all over the country and each time we had a blast.

Over the years, we held our reunions in fancy cities all over the country—Las Vegas (that one was a blast), New Orleans, San Diego … These get-togethers were always fun, and I enjoyed spending time with these guys, fellows I once saw combat with. We never had what I would call a bad reunion. Of course, money was often a problem. It was sometimes difficult to get hotels to give us a price break on our stays, so that we could afford to go. Naturally, I did my best to put a guilt trip on the manager, and it usually worked, especially if he was a veteran.

In 1995, having had reunions all around the country we had one again at the Harley Hotel. Russ Diefenbach, now 70 (I was 73), our No. 3 gun loader, was there, he bought an expensive $250 bottle of cognac, something called Marquis de Caussade Armagnac.13 We decided at that reunion that the last living survivor of the unit would drink that bottle for all of us—sort of like a tontine.14 At the end of the reunion, Russ decided to turn the bottle over to me for safekeeping. I was its caretaker for 14 years. As the years kept rolling though, and we passed our sixth decade since the war had ended, and as more and more of us died, I realized that we were getting close to the end, and to be honest, I did not want to be the last Marine that would be drinking to his buddies.

I finally decided that that was not going to happen. Those few of us that were left, about 15 guys, could have one last reunion and all share the bottle. I proposed that idea to them. I told them with a chuckle that I figured I would probably be the last guy anyway, and that I didn’t want to drink that damn bottle all alone.

They mostly laughed at that, but they all agreed. On Saturday, August 29, 2009, 64 years after the war’s end, we had one last get-together in Columbus. We met at that nice Hotel Hilton in the Easton Shopping Center. I drove over there wearing my bright red Marine Corps League jacket and my ribbons, of course. Finally, the time came, and we cracked open the brandy. Unfortunately, the flavor was disappointing. I guess you’re not supposed to keep good brandy in the refrigerator, especially for some 14 years.

The guys stayed at the Hilton that night, and we had a few more “sessions” in a couple of the rooms. In the end though, I was sorry to see my buddies leave, because I figured it would be the last time that I would see most of them, well, alive. I was right. Two of them died right after that reunion: Wilber Cox, a replacement corpsman, and Richard Radke who had been one of our ammo carriers and later had retired as a lieutenant colonel in the Army. And since that time, another eight or nine have gone on.

1 China–Burma–India. This was a term used during the war to differentiate actions, supply points, and individuals serving from those in the Pacific Theater, even though it was technically never classified as a “theater” in an organizational sense. It encompassed China and Southeast Asia. The most famous units to serve there were the prewar Flying Tigers, Merrill’s Marauders, and Army Air Corps units flying the “Hump” over Burma. After Okinawa, the 1st Marine Division was sent there.

2 Originally 1st Raider Battalion, and later designated 4th Battalion, 1st Marines.

3 Across the Mississippi River and just north of St. Louis.

4 Norman’s grandfather, William Leishman had overseen construction of the Rose Bowl Stadium in the early 1920s. The Tiffany-designed Leishman Trophy, which is given each year to the winning team at the Rose Bowl, is named after him.

5 After the war, Curtis Beall was sent to China, where he was wounded and received the Purple Heart in 1945. He returned home in 1946 and went back to the University of Georgia, where he finally graduated in 1947. He also went back to being a cheerleader, and at 24½, he ended up the oldest student ever to cheerlead there. For several years he worked as a government instructor on agriculture to veterans and later became president of Federal Land Bank, before going into business on his own. His firm, Beall’s Christmas Trees, started in the late 1970s, once boasted over 48,000 Christmas trees. He also served for nearly three decades as the president of Dublin’s Federal Land Bank Association. Beall died on January 10, 2013 from prostate cancer at the age of 90. He was buried in the Brewton Community Cemetery in Dublin, Georgia.

6 Imlay is located along Interstate 80, about 15 miles south of the Thunder Mountain Indian Monument and some 130 miles northeast of Reno. It has a population of about 170. It was once a modest railroad town, now all but abandoned.

7 The Dalles (pronounced “Dales”) is a city in Oregon about 84 miles east of Portland, with a population of 13,600.

8 Tules (pronounced tOO-lees) are country plants that thrive in swamps and marsh areas on the West Coast. Western Indian tribes used to harvest them and fashion them by dyeing and weaving them into baskets, bowls, sleeping mats, and head coverings.

9 Cpl. John Donald Skoglie died on December 2, 2007, and was buried in the Northern Nevada Veterans Memorial Cemetery in Fernley, Nevada.

10 Marine Aircraft Group 12, created in March 1942 in San Diego.

11 Joe B. Dodge was born September 9, 1924, and died of cancer November 26, 2013 at the age of 89.

12 Karl Tangeman had been on one of the mortar teams, and had seen action with them on Guadalcanal. Wounded twice, he was evacuated to Brisbane, Australia. When it was discovered that Karl was only 15 years of age, he was immediately transferred out of the platoon and sent back home. As soon as he turned of age, he reenlisted in the Marines. He was though, never reassigned to the mortar platoon.

13 It is considered by connoisseurs as one of the oldest, finest VSOP (very superior old pale) distilled brandies in the world. It is similar to cognac, averaging 84 proof. Once consumed for medicinal purposes (really), it is still produced in the Armagnac region of southwest France near the Pyrenees.

14 A tontine is a dedicatory custom in which survivors of a war unite together create a fund or, in this case, purchase a rare vintage bottle of wine or spirits, with the idea that the last living survivor drink it on behalf of his other departed comrades and to commemorate their memories in a toast. The idea perhaps came to Diefenbach after watching a similarly themed 1980 M*A*S*H episode entitled “Old Soldiers.” In the TV show, the 4077th’s commanding officer, Sherman Potter, is involved in such an experience on behalf of the old war buddies he served with in France in World War I. More likely though, the last-man bottle idea was borrowed from a similar arrangement for the 1st Marine Division Association. In 1946, the association was donated a bottle of rare 50-year-old Jph. Etournaud cognac (insured for $25,000), a gift from World War I Marine veteran Ralph McGill, editor of the Atlanta Constitution. Presumably, the bottle, last reported to be at the Marines Memorial Club in San Francisco, is still unopened.