TREND 6

Globalizing Surveillance

From the Domestic to the Worldwide

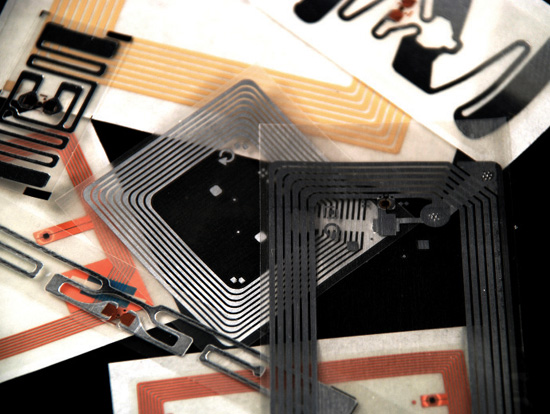

The term global surveillance evokes international espionage and the spreading tentacles of clandestine intelligence agencies—the stuff of spy thrillers and, more soberly, organizations such as the US National Security Agency (NSA). Such global monitoring exists, of course, but much more mundanely, global surveillance may now also refer to international standards for airport security or simply to tagged consumer goods with standardized codes. Your razor blades or your blouse may contain an RFID tag conforming to a universal electronic product code and associated with global data synchronization. These grand technical terms matter little, but what they point to is a world in which data connections allow the blades or the blouse to be traced back to their producers or forward to the person currently using them.

Processes that used to be separated by national borders are increasingly connected beyond those borders. The globalization of surveillance, then, refers to how information once held in national silos is now more typically digital and thus flows more easily across borders. One may use a credit card, for example, to make purchases in another country, and personal details accompany such transactions. We have also become more aware of these connections, these data flows. We expect similar security regimes in airports everywhere, and we are aware that our passports are machine-readable around the world. Those scanners recognize our identification details even though the country we are in may be geographically and culturally remote from our own.

Surveillance in Canada is deeply affected by broad global trends. American politics and policies are one obvious source of influence, but the global surveillance connections extend much more broadly. These global influences may involve subtle efforts to shape policy directions, the sharing of expertise, or compliance with international standards and regulations. For example, in 2007, Canada signed a “partnership” agreement with Israel to cooperate on public safety.1 Given that Public Safety Canada works cooperatively with the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA), the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), and Correctional Services of Canada (CSC), surveillance practices have to be central to this international arrangement. Israeli security uses ethnic-profiling practices—so does this mean that Canada will also extend such discriminatory techniques to its border?2 Whatever the specifics, to appreciate both the contemporary and future dynamics of surveillance in Canada, one must think about Canada in the context of globalization.

Surveillance has been greatly affected by globalization. People are as likely to be observed by video surveillance cameras whether they are in Toronto, Johannesburg, or Tokyo. National identity card systems can be found in the Netherlands, India, and Brazil. But it is not simply that similar technologies are used or that the same technology companies operate in different countries: surveillance processes and procedures are becoming more alike. No matter which country you travel to, at the national border, you are likely to be asked similar questions and subjected to similar kinds of observations. Frequently, international processes—the use of automated teller machines (ATMS), for example—connect to networks that share information globally.

The globalization of surveillance is not a finished process; it is ongoing. This does not mean that the same surveillance practices occur everywhere, even though many may be widespread. Although surveillance cameras are used in different cities around the globe, for instance, they are not necessarily conducting the same form of surveillance. Systems can differ in terms of both the groups of people being watched and the underlying reasons for their monitoring. Indeed, such systems may not involve a human watcher at all: video camera footage is now often simply recorded without observation and is increasingly monitored by automated software systems.

Despite the frequent similarities in surveillance around the world, the networks that connect surveillance systems are not necessarily global; they may involve local networks created for local purposes. In London, England, the city with the highest density of video surveillance cameras in the world, two cameras located very close to one another may be part of entirely different systems operated by different local authorities or police forces. If you tried to connect them, you would discover that they are incompatible. Some are still analogue, recording to VHS tape; some are digital and cable-connected; some transmit information wirelessly. Likewise, some are watched by dedicated operators in control rooms connected to the police, while others are sporadically monitored; some merely record, and some are “dummy” systems that merely resemble surveillance cameras. There is no seamless transfer of video surveillance images around London, let alone around the world, despite the ambition of security professionals to move in that direction.

These differences are compatible with globalization because globalization does not mean homogeneity. Thinking about the globalization of surveillance involves recognizing both similarities and differences in surveillance around the world. National borders and national cultures still matter. Canada is just one kind of national surveillance society. China, for instance, practices a form of totalitarian surveillance that is still functionally compatible with capitalist economic development. Intensive surveillance of political and cultural views and opinions in China can result in significant impacts on individual dignity, life chances, and freedom. There are also significant differences among Western states. Some European states, such as Germany, have constitutional rights that make it more difficult to adopt technology-dominated surveillance. Sweden, in contrast, treats much of the personal information gathered by the state, such as the data in an individual tax return, as public property and makes it publicly accessible. In the rapidly developing economies of Brazil and Mexico, it is normal for wealthier citizens to eschew the limited protections offered by the state and opt for private security and surveillance providers, and for the poor to be left unwatched and undefended unless they turn to one of the many gangs that are the source of the more privileged citizens’ fears.

Globalization Processes

There are many processes of globalization, or, to be more precise, different processes, practices, policies, and technologies are being globalized in different ways and at different speeds. Forms of globalization that are related to surveillance are discussed here under four interconnected themes: globalizing regional interests, globalizing governance, globalizing standards, and globalizing technologies.

Globalizing Regional Interests

Artificial satellites orbiting the earth constitute one of the most global of surveillance systems in terms of their coverage. Most of these satellites are controlled by military organizations—in particular, the US military. Near the end of the Cold War, the United States achieved control of orbital space, which allowed it to seize the “high ground.” The US government has since claimed the power to deny other countries access to orbital space if it considers that use a threat to American interests. So while satellite surveillance appears to be global, it would better be described as serving regional interests: “globalization” here means the globalization of US military power.

Similarly, the United States dominates global communications. The Internet—a US military Cold War innovation that was originally intended as a form of self-repairing communication in the event that total war destroyed conventional forms of communication (the Internet reroutes around damage)—remains largely under US-based administration. A key example is ICANN (the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers), the organization that decides how Internet domain names and addresses are assigned to countries and other bodies. The Internet, like other communication systems, has produced new freedoms and ways of sharing and organizing between people. Its protocols, however, depend upon automatically sorting and categorizing vast amounts of data. Although one might think that it would be impossible to manage all of these data, the problem of volume is proving to be a technical one. US intelligence—in particular, the National Security Agency (NSA), through its ECHELON and PRISM systems—can use back doors in communications hardware and software to tap into, siphon, and sift much global communications traffic, including the Internet, email, telephone, fax, and telex.*

Although other nation-states monitor and control the Internet and, like China or Iran, may do so with greater effect within their national borders, those countries do not have the global reach of the United States. This is, in part, because the United States has enlisted allies into its surveillance practices. In the case of ECHELON, the Canadian Communications Security Establishment (CSEC) is a “first party” to the agreement that underpins this global system of communications interception and analysis under the secretive 1948 CANUSA treaty.3

Globalizing Governance

Many forms of surveillance operate at global levels as part of global institutions—like the World Health Organization, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF)—that exist largely to monitor global information flows in a variety of domains, from the economic to the environmental. Some of these surveillance systems, particularly those concerned with environmental change or the monitoring of human or agricultural diseases, provide desirable public benefits. In other areas, this is more debatable. A large proportion of contemporary surveillance at the global level exists to protect commercial interests, or to advance the globalization of capitalism itself.

Agencies that operate at a global level, such as the IMF, have a clear surveillance function, and their activities alter the destiny of millions, as, for example, when a national economy requires “structural adjustment” to meet IMF criteria for economic stability. Until recently, this was a process associated largely with the imposition of an Anglo-American economic model on emerging colonial countries (although even the United Kingdom experienced structural adjustment in the global economic downturn of the 1970s). The most recent example, however, is the imposition of harsh conditions on Greece and Italy in return for financial bailouts, as well as the removal of democratically elected governments and their replacement by IMF-approved technocrats to manage the hoped-for economic recovery. In the global economy, control is often exercised at national levels through providing credit and subsequently monitoring almost all aspects of a state’s economy, not only in order to facilitate repayment but also to ensure the state’s compliance with the norms of international economic competition more broadly.

This is similar to how banks and other financial institutions use information that they acquire through surveillance (including clients’ personal and financial data from both the bank itself and external credit-rating agencies, as well as “softer” information acquired via interviews and meetings) to make decisions about the services that they offer individuals. The combination of data from different sources results in profiles that determine the suitability of applicants for loans and other services. Nation-states are subjected to comparable kinds of dataveillance and profiling: public and private information companies collect and collate data and perform both human and, more commonly, algorithmic judgments on data relating to nation-states and then profile these countries to assess their credit-worthiness and relative place in global markets. As with the consumer-banking and credit-rating systems, much of this global economic surveillance infrastructure is corporate and not run by nation-states or democratic international organizations: the credit-ratings agencies that define the credit-worthiness of nations—including Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s, and Fitch Ratings—are private companies accountable to no one but their shareholders.

Globalizing Standards

The third form of globalization that is important to surveillance is standardization. Increasingly, global expert and technical forums—such as the Frame Relay Forum, which determines the physical characteristics of telephone and other communication hardware connections, or intergovernmental gatherings such as the G20 summits or OECD meetings—set global standards relating to security and surveillance. In the past, such standards might have related solely to technologies. These standards are significant in their own right since they influence the ease or difficulty with which states can monitor communications systems. However, with the creation of the International Organization for Standardization’s (ISO’s) Societal Security standard, which includes technical standards for everything from emergency evacuation procedures to video cameras for security purposes, standards now relate increasingly to practices, including security and surveillance practices.4

Much of this standardization combines state and corporate interests. Most technologically advanced states have (or have proposed) laws that require Internet service providers (ISPS) to hand over personal traffic and/or content data to the police, and to block those who contravene copyright and licensing regulations from accessing the Internet. An example is ETSI, the European Telecommunications Standards Institute, whose global reach means that standards for the lawful interception of communications are applied worldwide. Here, the globalization of intellectual property rights meets the globalization of communications and computing, and the response of states has been to favour the smooth flow of commercial content. In other words, state surveillance supports state security and competition between corporations and does not necessarily take into account the interests of individuals or groups.

Globalizing Technologies

Finally, many aspects of the globalization of surveillance occur through more elusive and opaque processes. For example, video surveillance has spread globally largely through policy transfer between nation-states and, more importantly, through the exchange of “lessons learned” among members of the private sector (including technology companies and private security agencies), police forces, and local governments, as well as those dubbed by some as “travelling technocrats.”5 In turn, policy transfer relies on fact finding, conferences, courses, and the sharing of best practices in professional publications. Many of the visible material forms of surveillance that one sees more and more often, especially within the globally connected “World Cities”—including Toronto, Montréal, Calgary, and Vancouver—are the result of such semi-formal processes of global knowledge-sharing, marketing, and policy learning.

The spread of surveillance thus occurs almost independently of academic or third-party assessments of its effectiveness. For example, academic studies in the United Kingdom clearly show that surveillance cameras fail to meet their crime-fighting objectives.6 Yet, despite this evidence of their ineffectiveness, the use of such cameras has mounted, as other countries follow the UK’s example. Surveillance cameras are now so established as a trusted item in the professional toolbox of urban management and policing that their failure is often viewed only as a problem of implementation or of insufficient technology, never as a problem potentially inherent in the technology itself.7 Within the closed and self-reinforcing world of militaries, police, and security technology companies, all too often profit and influence follow from promoting surveillance technologies, regardless of what academics and advocates may conclude about their effectiveness or social costs.

The Globalization of Surveillance in Practice

The following section outlines four key globalized phenomena that have affected, and will continue to affect, Canadians in the twenty-first century: border control; the related issue of migration and undocumented people; the global movement of mega-events, such as the Olympic Games; and the increased use of unmanned aerial vehicles, or drones.

The Transformation of Canadian Borders

Many of the developments outlined above are motivated by concerns about the increased mobility of people, goods, and information. Globalization has meant that raw materials and products travel further and faster than previously, and so, too, do people, from elite global business travellers and officials, to tourists, to the masses of migrants seeking a better life or escape from war, disaster, and poverty. Along with the movement of people and goods come security threats and the risk of disease, as well as economic, cultural, and political challenges. Moreover, information circulates even further and faster than either material goods or people, and this includes information about those goods and people. Although information is constantly being sorted, there are still particular points where global circulations of bodies, goods, and information all intersect—and borders are one such place.

The Canadian border, like all borders, is being transformed. There are simultaneous local and global pressures to “open up” (on economic grounds, to facilitate flows of people and goods) and to “close down” (on security grounds, to regulate people and cargo perceived to be a risk). Two main Canadian bodies deal with borders. The Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) is the primary body responsible for border security. Established in 2003, the CBSA now manages 119 land-border crossings and thirteen international airports. The second major border agency is the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority (CATSA). Founded in 2002, CATSA is responsible for preboarding screening (passengers and their belongings), baggage screening, nonpassenger screening, and the implementation of restricted area identity cards at eighty-nine airports, both international and domestic.

Other state bodies, like Citizenship and Immigration Canada, the RCMP, and the CSIS, cooperate with CBSA and CATSA on border security. In the far North, the Canadian military operates remote patrols. The North is likely to become a more significant site for border surveillance as climate change reduces the covering ice, opening potential sea routes and mineral exploration and leading to territorial claims from multiple states. However, monitoring the North is proving to be expensive and complicated. In 2008, the Canadian government proposed a drone-based Joint Uninhabited Surveillance and Target Acquisition System (JUSTAS) to monitor the far North, but that initiative continues to increase in cost, especially as it is pushed further into the future. In late 2012, the project was estimated to cost $1 billion and to be delivered in 2017.8

The Canadian border is essentially a triage point in a complex set of global flows of people, information, and things. But much of the work in establishing who and what can and cannot enter is not done at the border itself: it occurs elsewhere and prior to arrival. New global standards are being developed to track and verify goods and people. Shipping containers are frequently tagged with radio frequency identification (RFID) chips that closely monitor their movements. Some specific cargo, including most live animals (and most animal carcasses), must also be chipped. Although people are not tagged, a machine-readable passport containing an RFID chip is becoming a global standard, as are basic biometric identifiers, such as fingerprints and facial photographs. In addition, data from passenger name records (PNRS) or advance passenger information (API) are widely shared across borders.9

Such cross-border sharing can cause problems because other countries may not have the same provisions as Canada has to protect privacy, data, or even due process. In recent years, Canada has put in place several agreements and border-security programs and has increased data exchange with the United States and the European Union (EU). The EU’s main privacy framework, known as the General Directive, is highly compatible with Canada’s privacy legislation. The General Directive, originally passed in 1981 and revised in 1995, has become a global standard, since it was the first legislative framework created for protecting personal data.10 In contrast, the United States has no comparably comprehensive personal information protection; rather, it has particular acts for certain sectors, such as banking and health, and more generalized statements in its privacy acts. Nor is there a federal legislative framework in the United States for protecting personal data collected at borders. To further compound matters, in 2007, the American government exempted its passenger-monitoring program, Secure Flight—otherwise known as the no-fly list—from its already limited US Privacy Act.

The influence of the United States on Canada can already be seen in data-sharing schemes and in special agreements between the two countries that enable US border guards and police to operate on Canadian territory (at international airports, where one now enters US territory within Canadian airports when going through US customs). However, in some cases, Canada has had a more ambivalent attitude to the border surveillance introduced by the United States. For example, Canadian border agencies have only partially followed the US example in adopting full-body scanners. Increasingly, evidence suggests that the body-scanning technology most commonly used in US airports—backscatter X-ray, which produces pictures that are difficult to blur (blurring is necessary to ensure privacy)—may pose a health hazard. Consequently, in 2013, the US Transportation Security Administration started to remove backscatter X-ray machines from its airports.11 In contrast, airports in Canada employ millimetre wave scanners, which do not raise the same health concerns, and Transport Canada has attempted to follow strict privacy guidelines in their use.12 Canada has also kept the scanning process voluntary. Moreover, whereas scanners have become routine in the US, with the option of a physical search available to passengers who object to scanning, in Canada it is the other way around: passengers who would prefer not to be physically searched can instead choose the scanner.

Issues about the Canadian border typically include the United States, and not simply because we share the world’s longest land border. The strategic reach of the United States and its claims over airspace and defence have intensified since 9/11. During this period, the security agenda has joined with ongoing international economic liberalization. The latter has progressed since the inception of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994, to the point where, in the opinion of some, the logical progression in border control is a “North American security perimeter.”13 This would essentially mean that Canada would adopt US rules for Canadian border interactions in return for easing the restrictions that make it increasingly difficult for people and goods to cross into the United States.

In early 2011, Prime Minister Stephen Harper and President Barack Obama signed a formal declaration entitled “Beyond the Border: A Shared Vision for Perimeter Security and Economic Competitiveness.” The two countries promised to “work together to establish and verify the identities of travellers and conduct screening at the earliest possible opportunity” and to “work toward common technical standards for the collection, transmission, and matching of biometrics that enable the sharing of information on travellers in real time.” This implies that intimate personal data will now be transmitted between the two countries instantaneously. In addition, the two countries “expect to work towards an integrated Canada-United States entry-exit system, including working towards the exchange of relevant entry information in the land environment so that documented entry into one country serves to verify exit from the other country.”14

Undocumented Migrants

Increased migration is one of the most significant facets of an interconnected world. The United Nations Population Division estimates that almost 214 million people migrated from one country to another in 2010.15 Canada is a country built on immigration. With the exception of First Nations peoples, everyone in Canada either descends from immigrants or is an immigrant himself or herself. Furthermore, many immigrants—including important figures in Canadian history—arrived without documentation or with dubious legal backgrounds.

For migrants, the logic of border control and surveillance now starts long before they reach the physical border, with attempts to acquire legitimate papers and identification for entry into desirable countries like Canada. Identification has become another major global business and often forms the infrastructure for surveillance—whether at borders or within nations. However, despite Canada’s economic need for more migrants, many people are unable to acquire the necessary documentation. Canada’s immigration regime has been tightening, which has created more onerous and time-consuming processes and has excluded certain categories of people—particularly, the “unskilled” and less educated.

The result has been a rise in the number of migrants who do not have the documentation or permissions that Canada now requires for entry. Estimates of undocumented migrants to Canada are unreliable, ranging between thirty-five thousand and five hundred thousand. Because they lack the forms of identification, visas, and other documents that would allow them to negotiate the increasingly complex web of administrative surveillance, undocumented migrants face three types of inequality: unequal rights, unequal risk, and unequal speed.16 Undocumented migrants are denied medical care, social security, and the basic protections that Canadians take for granted. People are singled out for questioning, search, and exclusion from entry, often because of prejudice, misidentification, or unwarranted assumptions.17 Canada is not alone in this: in the EU, migrants face increased criminalization, restrictive migration laws, and a growing climate of fear. There is particular concern over the treatment of the children of undocumented migrants, which includes their frequent imprisonment in some countries.18 The police, particularly the RCMP and the CBSA, target undocumented migrants for further intensive surveillance in the name of tackling “people trafficking.” However, many undocumented migrants are unwitting subjects of such surveillance simply because they have overstayed their visas or arrived in Canada on closed, single-employer work permits only to find their employers abusive or unwilling to deliver the (minimal) wages and conditions promised. As such individuals attempt to live a life under the radar of state surveillance, they constitute a cheap, vulnerable, and marginalized workforce employed by Canadian companies to do menial jobs.

A Canadian passport: the end result of a complex surveillance process (Source: © iStockphoto.com/AndrewWilliam)

The migrant situation reflects the fact that while identification and passport standards have become increasingly standardized, there is no formal international regime to govern the border-crossing mobility of people.19 Existing provisions tend to be limited to conventions regarding skilled workers. Even in situations where a global governance framework does exist, as with refugees whose right of asylum is guaranteed by the United Nations, the situation is not much better.20 The United Nations Population Division estimates that there were almost 16.5 million refugees globally in 2010, most of whom were merely temporary refugees from neighbouring states.21 This is a surveillance issue because official decisions made about whether someone may cross a border depend upon personal information contained in documents or in related databases. How such information is gathered and interpreted has direct consequences for those waiting to hear the response to their request to be allowed entry.

Canadians are proud of their reputation for offering refuge to those escaping persecution, whether slaves fleeing the United States, Sikhs from the Punjab, or “boat people” from Vietnam. However, recent Canadian legal reforms have moved in the opposite, less welcoming direction. The latest changes redesignate some of those claiming asylum as “irregular arrivals” and also establish a list of “safe countries” (twenty-seven in 2013) from which claims for asylum will generally not be considered.22 These “safe countries” include Hungary, which means that Roma people from Hungary cannot seek asylum in Canada despite the fact that they face a level of persecution that makes it difficult for them to remain in that country. Many such nomadic peoples that previously sought refuge in Canada may even be denounced as “bogus” and “criminal.”23

Canadian Cities and Mega-events

Major Canadian cities compete globally for resources and prestige.24 A major marker of global status is the ability to attract mega-events, including gigantic sporting competitions, such as the Olympic Games and the FIFA World Cup; international political conferences, such as the G20, G8, and United Nations summits; and major cultural and commercial festivals and exhibitions, such as World Expos. When incidents like the bombing of the Boston Marathon route (April 2013) occur and street camera footage is used forensically to confirm the culprits’ identities, it is not surprising that expanded surveillance is seen as a means of bolstering security.

Of course, not all mega-events are the same. But while events where a (paying) public is invited, such as the Olympics, and those that are closed to nonparticipants, such as the G20, have quite different dynamics, among the features they share is the use of exceptional forms of security and surveillance that may temporarily supplement, replace, or conflict with national and local laws.25 An example is the infamous “FIFA World Cup Courts” in South Africa in 2010, in which the soccer authorities virtually took over a function of the justice system. They prosecuted fans and others for entirely new crimes against the FIFA World Cup competition, largely those connected with breaching the exclusive marketing rights of sponsors—for example, by wearing clothes with the brands of rival companies.26 These exceptional measures are often demanded as a condition for hosting such events and are increasingly standardized across cities, regardless of national or local practices and customs. For example, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) now makes security a key part of the official evaluation process, and, in a good example of the processes of global “lesson-learning” mentioned above, the IOC facilitates the sharing of best security practices between former and future host cities.27

Thus, the surveillance measures deployed in cities hosting mega-events increasingly come to resemble each other. Vancouver during the 2010 Winter Olympics and Toronto during the subsequent G20 meeting both featured intensive police surveillance of political activists, surveillance that many found intimidating and that was designed to pre-empt both crime and legitimate protest.28 Police also deployed open street video surveillance systems together with pictures taken with handheld photographic and video cameras, which they then uploaded to social media in order to identify activists at these events.29

Such events are frequently test beds for new surveillance technologies, and the technologies used often persist beyond their deployment at the event. In the case of Vancouver, the Winter Olympics were clearly used to justify installing video surveillance that might not have been politically acceptable in normal circumstances. After the G20 summit in Toronto, however, only a few surveillance cameras were left in the downtown area, but the police stored the remaining cameras for potential future use.30 Mega-events outside Canada have introduced other experiments. Chemical-sniffing robots were used at the FIFA World Cup in Germany in 2006, and the 2007 Pan-American Games in Rio de Janeiro featured high-flying surveillance airships.31 Smaller unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVS, about which more below) kept an eye on the UEFA European Championship in Switzerland and Austria in 2008, and for the Olympic Games in London in 2012, biometric entry systems were installed.32 Increasingly, these technologies are redeployed at subsequent events as standard practice.

Many of the cities hosting these events have temporarily redesigned their streets to increase security and surveillance. The strategy of “island security,” for example, involves isolating the site of the event within the city and is based on the “Ring of Steel” tactics used by the British authorities to deal with terrorism in Belfast and London.33 This is now standard practice for G20-type meetings and sports mega-events. Such events now also increasingly involve changes to urban roads and paths, as well as the use of controlled “fan zones” that isolate spectators in fenced-off video-viewing areas that allow for surveillance and control of a potentially unruly public. These areas are frequently designed to subject fans to a combination of saturated marketing and surveillance for commercial purposes.34

Mobile Surveillance and Drones

Another form of increasing global surveillance features remotely operated aircraft. Popularly known as “drones,” these pilotless devices were originally called remotely piloted vehicles (RPVS), or unmanned aerial (or air) vehicles (UAVS). According to a recent US Government Accountability Office (GAO) report, more than fifty countries are now developing nine hundred UAV systems, and seventy-six countries currently operate UAVS.35 Of the latter, only three—the United States, the United Kingdom, and Israel—operate armed UAVS; most are purely surveillance devices. The global market for UAVS has been called “the most dynamic growth sector of the world aerospace industry”; it is currently worth around US$6.6 billion per annum and is expected to almost double to US$11.4 billion over the next decade.36

Government secutiry operations account for a great deal of this growth. US Customs and Border Protection now patrols the US-Canada border with the same Predator drones that it uses in Pakistan. As noted above, the Canadian government has been less successful in its attempts to procure UAVS for border patrol in the far North. UAVS are also increasingly applied in civilian markets. New and powerful industry associations advocate for national domestic and private commercial use of UAVS. Internationally, the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) lobbies on behalf of drone manufacturers, and in Canada, an affiliated group, Unmanned Systems Canada (unmannedsystems.ca), was created in 2010 from the merger of two smaller groups. These industry bodies lobby to limit regulation to what they believe is strictly necessary.

UAVS are used by certain Canadian military and police units, such as the RCMP in British Columbia and Saskatchewan, and the Ontario Provincial Police.37 They are used for coastal surveillance, as well as for obtaining images of highway accidents and for other types of law enforcement checking and monitoring tasks.38 Drones are also used for a number of public activities outside of policing: from the real-estate sector, for dramatic but inexpensive aerial marketing videos of large properties (where their use has increased substantially), to NGOS, for monitoring corporate environmental abuses.39 Drones are also used by forestry trusts, environmental researchers, and private corporations to survey and assess otherwise inaccessible areas.40

Drones, now increasingly used in civilian contexts (Source: © iStockphoto.com/alexsalcedo)

Most military UAVS, which tend to be similar in size to conventional piloted aircraft and can operate for long distances and time periods, are significantly different from the drones used in domestic contexts. The latter—often referred to as micro- or mini-UAVs, or MAVS—tend to be small, lightweight (some are compact enough to fit in a backpack), and easily operated, and in many cases, they resemble hobbyist remote-control kit aircraft. The personal and institutional use of UAVS is therefore apt to increase.41 Industry reports suggest that the growth of civil markets for UAVS is held back only by national aviation regulations.42 Yet citizens, civil rights groups, and privacy regulators all have good reason to be concerned with the growth of domestic human-related UAV surveillance. In the United States, a Congressional Research Service report recently highlighted such concerns, and the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) has testified before Congress that UAV use by police should have “a warrant requirement … as well as data use limitations, and transparency obligations for drone operators.”43 Canadians also need clarification about the corporate, personal, and police use of these devices. Thankfully, the popular media in North America is starting to raise such questions: a recent article in The Atlantic asked, “If I fly my UAV over my neighbor’s house, is it trespassing?”44

The decreasing size of drones has certainly made surveillance more portable and covert. However, a major area of research and development expansion in mobile surveillance devices is in biomimetic technologies. Biomimetics are machines that imitate naturally occurring animals or plants. The most common biomimetic devices tend to mimic birds, snakes, and insects. AeroVironment, a leading manufacturer of UAVS in the United States and the supplier of the most popular police helicopter drones, recently demonstrated a functional partially radio-controlled and partially autonomous robotic “Nano Hummingbird.”45 These developments show that visual surveillance is likely to become even more hidden, while losing none of its power.

Conclusion

Surveillance trends in Canada must be understood not merely in a national but in a global context of laws, standards, practices, technologies, and organizations. Globalization helps to accelerate the development of surveillance in all areas, particularly over the new global economy. Such surveillance touches ordinary consumers and travellers in their everyday transactions as well as in security-related fields. New global, international, or bilateral agreements frequently spell a formal commitment to new surveillance measures; examples of such agreements include no-fly lists, application programming interface (API) data, and border agreements with the United States. Globalization also results in an increasingly competitive and innovative marketplace for all surveillance technologies, from the most expensive military platforms to the cheapest private devices, including, for example, drones. Many of these technologies are also increasingly hybrid and are marketed with only minor variations for military and civilian uses. The spread of global norms, whether in the form of the ISO’s Societal Security standard or through more informal understandings of best practices that do not distinguish between different contexts and histories, can allow special security interests to appear neutral and can help to foreclose debate in the name of applying what is already apparently globally acceptable.

Notes

1 Rebecca Anna Stoil, “Israel, Canada Sign Security Accord,” Jerusalem Post, 29 November 2007, http://www.jpost.com/Israel/Israel-Canada-sign-security-accord.

2 See Andrew Stevens, “Surveillance Policies, Practices and Technologies in Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories: Assessing the Security State,” The New Transparency: Surveillance and Social Sorting, Working Paper 4, November 2011, http://www.sscqueens.org/sites/default/files/2011-11-Stevens-WPIV_0.pdf.

3 Philip Rosen, The Communications Security Establishment: Canada’s Most Secret Intelligence Agency (Ottawa: Parliamentary Library and Research Service, Parliament of Canada, BP343-E, September 1993), http://www.parl.gc.ca/Content/LOP/researchpublications/bp343-e.htm, 3.

4 International Organization for Standardization, Societal Security: Guideline for Incident Preparedness and Operational Continuity Management, ISO/PAS 22399:2007, http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=50295.

5 Wendy Larner and Nina Laurie, “Travelling Technocrats, Embodied Knowledges: Globalising Privatisation in Telecoms and Water,” Geoforum 41, no. 2 (2010): 218–26.

6 See, for example, Martin Gill and Angela Spriggs, Assessing the Impact of CCTV Home Office Research Study 292 (London: Home Office Research, Development and Statistics Directorate, 2005), https://www.cctvusergroup.com/downloads/file/Martin%20gill.pdf.

7 For a discussion of Canadian policy practices and rationales, see Sean P. Hier, Panoptic Dreams: Streetscape Video Surveillance in Canada (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2010).

8 David Pugliese, “Canada’s Drone Squadron Still Stalled, with Neither Planes nor Troops,” Ottawa Citizen, 27 December 2012.

9 Again, RFID-tagged passports and biometric identifiers were driven by the United States, originally through the G8 meeting in Sea Island, Georgia, on 10 June 2004. See Statewatch, “G8 Meeting at Sea Island in Georgia, USA, Sets New Security Objectives for Travel,” 2004, http://www.statewatch.org/news/2004/jun/09g8-bio-docs.htm.

10 “Directive 95/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 October 1995 on the Protection of Individuals with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data,” Official Journal L 281, P. 0031–0050, 11 November 1995, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:31995L0046:en:HTML.

11 Mike M. Ahlers, “TSA Removing ‘Virtual Strip Search’ Body Scanners,” CNN, 18 January 2013, http://www.cnn.com/2013/01/18/travel/tsa-body-scanners/index.html.

12 Transport Canada, “Full Body Scanners at Major Canadian Airports,” 16 April 2013, http://www.tc.gc.ca/eng/mediaroom/backgrounders-full-body-scanners-7131.html.

13 For a critical assessment, see Dana Gabriel, “The Integration of Canada into a U.S. Dominated North American Security Perimeter,” Global Research, 18 June 2013, http://www.globalresearch.ca/the-integration-of-canada-into-a-u-s-dominated-north-american-security-perimeter/5339525.

14 Prime Minister of Canada Stephen Harper, “Beyond the Border: A Shared Vision for Perimeter Security and Economic Competitiveness. A Declaration by the Prime Minister of Canada and the President of the United States of America,” 4 February 2011, Washington, DC, http://www.pm.gc.ca/eng/media.asp?id=3938.

15 United Nations Population Division, “International Migrant Stock: The 2008 Revision,” United Nations, 2009, http://esa.un.org/migration/.

16 Robert Pallitro and Josiah Heyman, “Theorizing Cross-border Mobility: Surveillance, Security and Identity,” Surveillance and Society 5, no. 3 (2008): 315–33.

17 For some examples and personal stories, see International Civil Liberties Monitoring Group, “Watch Lists and Border Controls,” 2010, http://www.travelwatchlist.ca/.

18 Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants, PICUM’s Main Concerns About the Fundamental Rights of Undocumented Migrants in Europe 2010, October 2010, Brussels, http://picum.org/picum.org/uploads/publication/Annual%20Concerns%202010%20EN.pdf.

19 United Nations Development Program, Overcoming Barriers: Human Mobility and Development, Human Development Report 2009, http://hdr.undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr2009/, 39.

20 For more on guaranteed right of asylum, see the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugee’s 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, both available at http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49da0e466.html.

21 United Nations Population Division, “International Migrant Stock: The 2008 Revision.”

22 Nicholas Keung, “Changes to Refugee System: Immigration Minister Jason Kenney Lays Out Criteria for ‘Safe’ Countries,” Toronto Star, 30 November 2012, http://www.thestar.com/news/canada/article/1296161--changes-to-refugee-system-immigration-minister-jason-kenney-lays-out-criteria-for-safe-countries.

23 Cynthia Levine-Rasky, “Who Are You Calling Bogus?” Canadian Dimension 46, no. 5 (2012): 12–14.

24 See Peter J. Taylor, World City Network: A Global Urban Analysis (London and New York: Routledge, 2003).

25 See, for example, Alessandra Renzi and Greg Elmer, Infrastructure Critical: Sacrifice at Toronto’s G8/G20 Summit (Winnipeg: Arbeiter Ring, 2012).

26 Marina Hyde, “World Cup 2010: Fans, Robbers and a Marketing Stunt Face Justice, Fifa Style,” The Guardian (UK), 20 June 2010, http://www.guardian.co.uk/football/2010/jun/20/world-cup-2010-fans-marketing-justice-fifa.

27 Philip Boyle, “Knowledge Networks: Mega-events and Security Expertise,” in Security Games: Surveillance and Control at Mega-events, ed. Colin J. Bennett and Kevin D. Haggerty (London and New York: Routledge, 2011), 184–99.

28 Jeffrey Monaghan, and Kevin Walby, “Making Up ‘Terror Identities’: Security Intelligence, Canada’s Integrated Threat Assessment Centre and Social Movement Suppression,” Policing and Society 22, no. 2 (2012): 133–51.

29 Daniel Trottier, “Policing Social Media,” Canadian Review of Sociology / Revue canadienne de sociologie 49, no. 4 (2012): 411–25.

30 “Toronto Police Want to Keep Most G20 Security Cameras,” CTV News, 15 November 2010, http://toronto.ctvnews.ca/toronto-police-want-to-keep-most-g20-security-cameras-1.575057.

31 See Francisco R. Klauser, “Spatial Articulations of Surveillance at the FIFA World Cup 2006TM in Germany,” in Technologies of (In)Security: The Surveillance of Everyday Life, ed. Katja Franko Aas, Helene Oppen Gundhus, and Heidi Mork Lomell (London and New York: Routledge-Cavendish, 2009), 61–80; and David Murakami Wood, “Cameras in Context: A Comparison of the Place of Video Surveillance in Japan and Brazil,” in Eyes Everywhere: The Global Growth of Camera Surveillance, ed. Aaron Doyle, Randy Lippert, and David Lyon (London and New York: Routledge, 2012), 83–99.

32 See Francisco R. Klauser, “Commonalities and Specificities in Mega-event Securitization: The Example of Euro 2008 in Austria and Switzerland,” in Bennett and Haggerty, Security Games, 120–36; and Pete Fussey and Jon Coaffee, “Balancing Local and Global Security Leitmotifs: Counter-terrorism and the Spectacle of Sporting Mega-events,” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 47, no. 3 (2012): 268–85.

33 Jon Coaffee, David Murakami Wood, and Peter Rogers, The Everyday Resilience of the City (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), chap. 6.

34 David Murakami Wood and Kirstie Ball, “Brandscapes of Control? Surveillance, Marketing and the Co-construction of Subjectivity and Space in Neo-liberal Capitalism,” Marketing Theory 13, no. 1 (2013): 47–67.

35 US Government Accountability Office (GAO), Nonproliferation: Agencies Could Improve Information Sharing and End-Use Monitoring on Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Exports, GAO-12-536, July 2012, http://www.gao.gov/assets/600/593131.pdf, 13, 9.

36 “Teal Group Predicts Worldwide UAV Market Will Total $89 Billion in Its 2012 UAV Market Profile and Forecast,” Teal Group, 11 April 2012, http://tealgroup.co/index.php/about-teal-group-corporation/press-releases/66-teal-group-predicts-worldwide-uav-market-will-total-89-billion-inits-2012-uav-market-profile-and-forecast.

37 See Alexandra Gibb, “Privacy Concerns Hover over RCMP Drones in British Columbia,” TheThunderBird.ca, 29 March 2012, http://thethunderbird.ca/2012/03/29/privacy-concerns-hover-over-rcmp-drones-in-british-columbia/; and Sigrid Forberg, “Taking to the Skies: New Tool Facilitates Investigations,” RCMP Gazette 74, no. 1 (2012), http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/gazette/vol74n1/trends-dernierestendances-eng.htm.

38 On coast surveillance, for example, see Colin Kenny, “Why Canada Needs Drones,” National Post, 28 February 2012, http://colinkenny.ca/en/p102659/.

39 On the former, see Neal Ungerleider, “Unmanned Drones Go from Afghanistan to Hollywood,” Fast Company, 15 February 2012, http://www.fastcompany.com/1816578/unmanned-drones-go-afghanistan-hollywood; on the latter, see Alexandra Gibb, “A Drone Field Guide,” Canadian International Council, Opencanada.org, 31 May 2012, http://www.opencanada.org/features/the-think-tank/a-drone-field-guide/.

40 Julia Horton, “Attack of the Drones to Fight Tree Rot in Scotland,” The Scotsman, 28 October 2012, http://www.scotsman.com/news/environment/attack-of-the-drones-to-fight-tree-rot-in-scotland-1-2602637.

41 See “Drones Work the Skies for Police, Scientists, Media,” CBC News, 22 March 2012, http://www.cbc.ca/news/technology/story/2012/03/22/technology-thecurrent-civilian-drones.html.

42 Steve Zaloga and David Rockwell, “UAV Market Set for 10 Years of Growth,” Earth Imaging Journal, 2011, http://eijournal.com/uncategorized/uav-market-set-for-10-years.

43 “EPIC to Congress: Protect Privacy Against Drone Surveillance,” 5 November 2012, http://epic.org/2012/11/epic-to-congress-protect-priva.html. See also Richard M. Thompson II, Drones in Domestic Surveillance Operations: Fourth Amendment Implications and Legislative Responses, Congressional Research Services, 3 April 2013, http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/R42701.pdf; and Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC), “Testimony and Statement for the Record of Amie Stepanovich, Association Litigation Counsel, Electronic Privacy Information Center, Field Forum on the Impact of Domestic Use of Drone Technology on Privacy and Constitutional Rights of All Americans,” 25 October 2012, Rice University, Houston, http://epic.org/privacy/drones/EPIC-Drones-Testimony-102512.pdf.

44 Alexis C. Madrigal, “If I Fly a UAV over My Neighbor’s House, Is It Trespassing?” The Atlantic, 10 October 2012, http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2012/10/if-i-fly-a-uav-over-my-neighbors-house-is-it-trespassing/263431/.

45 AeroVironment, “Nano Hummingbird,” 2013, http://www.avinc.com/nano. See also Kevin D. Haggerty and Daniel Trottier, “Surveillance and/of Nature: Monitoring Beyond the Human,” Society and Animals (2013), doi: 10.1163/15685306-12341304.