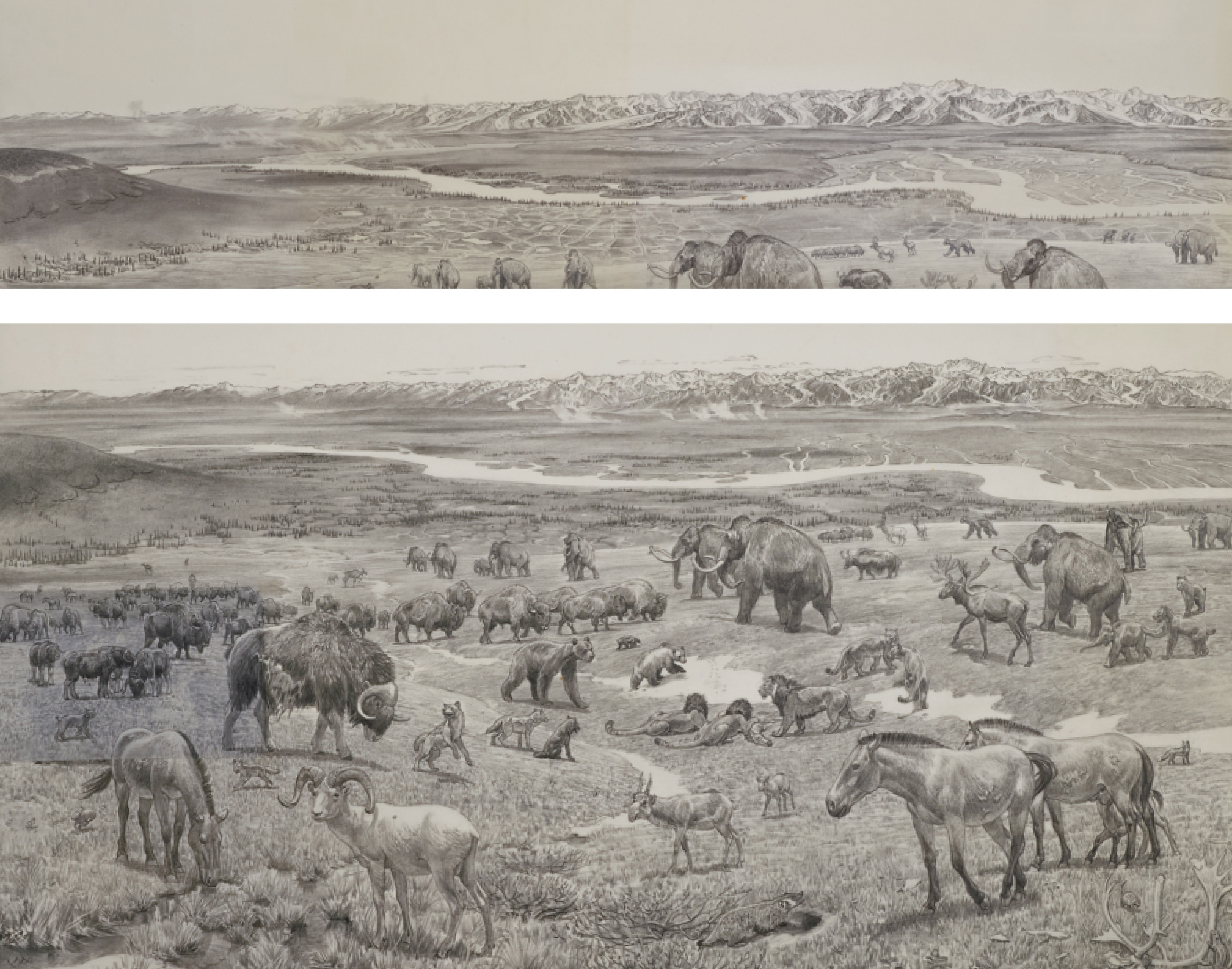

Gold-bearing gravels, Fairbanks region, central Alaska

Painted 1975

Acrylic on canvas; 12 ft., 5 in. H × 20 ft. W

Gold-bearing gravels, Fairbanks region, central Alaska

Painted 1975

Acrylic on canvas; 12 ft., 5 in. H × 20 ft. W

14,000 years ago

1 · Falco rusticolus (gyrfalcon)

2 · Castor (beaver) lodge

3 · Megalonyx (ground sloth)

4 · Homo sapiens (human)

5 · Alces (moose)

6 · Bos grunniens (yak)

7 · Mammuthus primigenius (woolly mammoth)

8 · Ovibos moschatus (musk ox)

9 · Cervus elaphus (elk)

10 · Cervalces latifrons (stag moose)

11 · Homotherium serum (scimitar-toothed cat)

12 · Camelops (camel)

13 · Mammut americanum (mastodon)

14 · Bootherium bombifrons (Symbos; helmeted muskox)

15 · Bison priscus (bison)

16 · Gulo gulo (wolverine)

17 · Arctodus simus (short-faced bear)

18 · Ursus arctos (brown bear)

19 · Panthera atrox (American lion)

20 · Lynx canadensis (lynx)

21 · Canis lupus (wolf)

22 · Lepus othus (Arctic hare)

23 · Alopex lagopus (Arctic fox)

24 · Ovis dalli (thinhorn sheep)

25 · Saiga tatarica (saiga)

26 · Mustela nigripes (black-footed ferret)

27 · Equus sp. (horse)

28 · Vulpes vulpes (red fox)

29 · Taxidea taxus (badger)

30 · Salix arctica (Arctic willow)

31 · Lemmus sibiricus (lemming)

32 · Rangifer (caribou)

33 · Urocitellus undulatus (ground squirrel)

Numerous details of the glacial landscape are among this mural’s highlights, many of them suggested to Matternes by University of Arizona glacial geologist Troy Péwé. As seen above, windblown dust, or loess, is carried aloft and eventually settles, often burying animal carcasses. Outwash from melting glaciers creates mud-filled, braided stream channels that drain into glacial lakes, while geometrically patterned ground forms in the upper portion of the permafrost as it thaws each summer and freezes in the following winter (right).

In the foreground, a woolly mammoth calf is harassed in a coordinated attack by a pair of scimitar-toothed cats (Homotherium serum), while the mother mammoth turns to intervene. Farther back, a mastodon (now known to have lived in earlier times) is distinguished from the mammoth by its wider body and flatter back.

Matternes used the Smithsonian’s mammoth skeleton (right) as the basis for his mural reconstruction; this specimen has recently been remounted at the NMNH in a new pose. Next he overlaid the superficial musculature (below right), forming the basis for the animal’s living form in the mural.

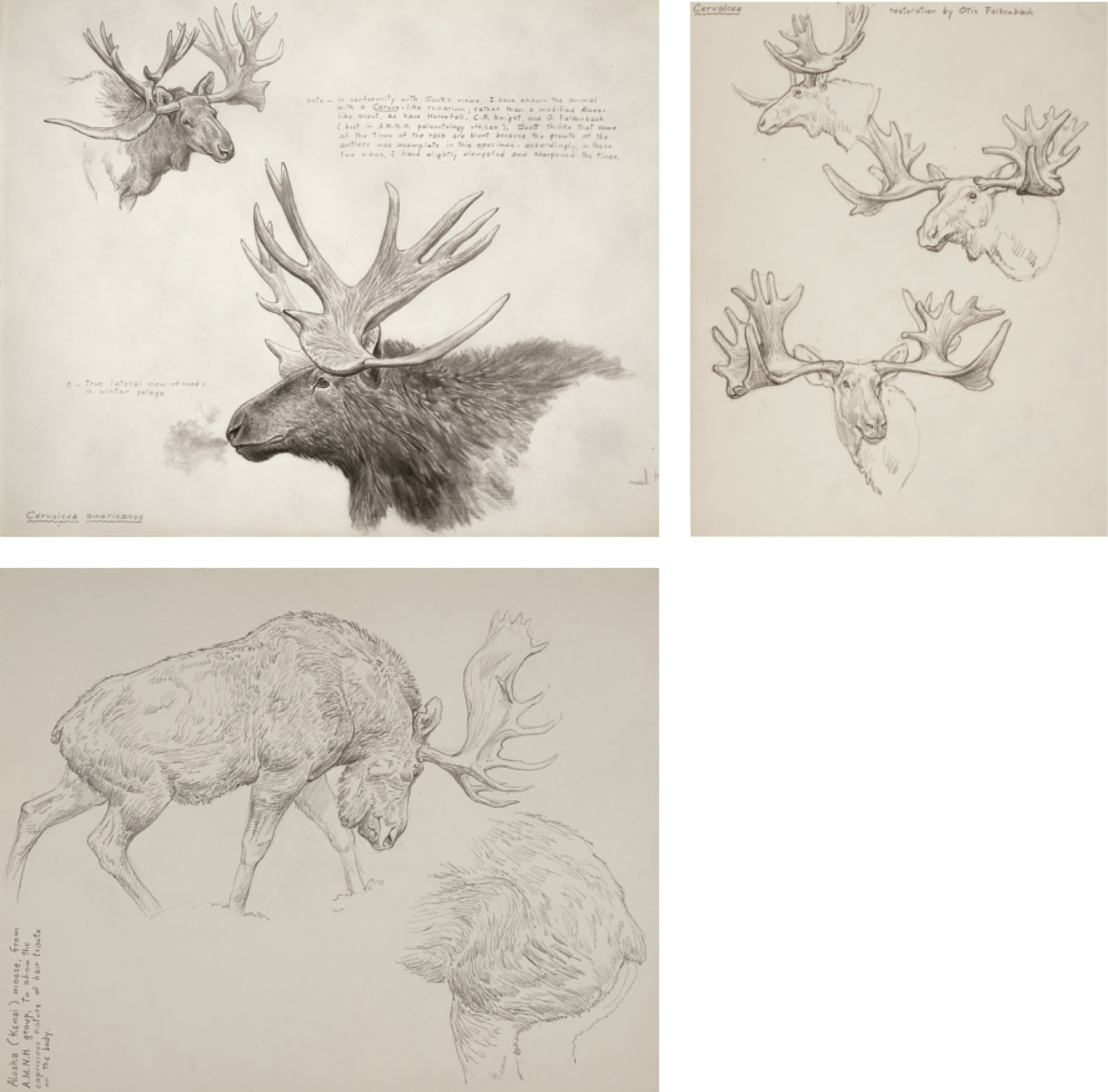

The great stag moose of the late Pleistocene (Cervalces latifrons) sported even more impressive antlers than its modern kin do. From the skeleton-based life reconstruction (opposite top), and often using prior drawings for reference (this page), Matternes developed a range of perspective views to show various behaviors of this now-extinct species. He sketched the present-day moose, at bottom left, from the AMNH’s diorama, for use as reference for the mural animal’s hair texture.

This spread beautifully illustrates the wide array of species that would populate the Alaska ice-age mural, from tiny voles and lemmings to giant elephants. They are categorized into four groups: elephants (proboscidians), ungulates, rabbits and rodents, and carnivorans—with red boxes denoting museum collections whose fossils Matternes used for reference. Note how different the short-faced bear (Arctodus simus) appears here compared to its final mural version (see this page).

Up into historical times, great herds of bison were characteristic of North American landscapes. Subtle differences between the ice-age species and the one we know today are reflected in Matternes’s painstaking studies of the animal’s skeleton, musculature, and external appearance (opposite). In the distance at right, some of the earliest human immigrants to the Americas hunt a giant ground sloth (Megalonyx).

Here the contrast between the mural’s different species of musk oxen can be seen. The helmeted musk ox (Bootherium, two left images below) had a less bulky body, flatter back, and higher-placed horns than its humpbacked, stockier living relative (Ovibos moschatus, bottom right). A third species, Symbos cavifrons (upper right), is now thought to represent females of Bootherium.

This freeze-dried mummy of the musk ox Bootherium (now known to be B. bombifrons), housed in the Frick collections of the AMNH, provided the artist a wealth of details on the species’ body proportions, form, and color.

Matternes grants each animal in the mural individuality by paying detailed attention to its position, behavior, and posture. Here a small female saiga antelope heads toward a larger horned male and away from danger; a preliminary sketch (opposite, lower left) captures its essence in economical lines. The rightmost American lion in the mural background began as a full skeletal reconstruction (opposite, lower right), which underpinned a lifelike restoration (opposite, top). Matternes then subtly altered the image in the final mural.

Matternes invested tremendous attention into the details of each species he reconstructed. He developed the mural’s short-faced bear (Arctodus simus) first as an articulated skeleton (right), individually drawing and measuring its bones from a specimen in the Field Museum. He then layered on the animal’s deep and superficial musculature (below left) and finally clothed it in finely textured fur (below right). These drawings include corrections that the artist made based on Finnish paleontologist Bjorn Kurtén’s (then lecturing at Harvard) suggestions that the original sketch had an extra lumbar vertebra. Opposite: Matternes often solicited outside advice from scientists such as Kurtén, in this case for his skeletal reconstruction of the cat Homotherium (then called Dinobastis).

Matternes provided even the smallest animals with fine detail and vivid behavior. A lemming gnaws at the bones of a dead reindeer (below) while a ground squirrel runs nearby (top). A black-footed ferret stands alertly (opposite, top left), while a badger guards its burrow near a patch of creeping Arctic willow (opposite, top right). The artist based the Arctic hare (opposite, lower left), seen bounding away from a hungry fox, in part on an exquisite ice-age mummy at the AMNH (opposite, lower right).

Mural development involved several stages, one of which was a full sketch layout (below) in which the artist brought together animals, plants, and landscape so that he could evaluate the overall mural. He modified it in subsequent versions (opposite) before transferring it to the wall canvas.

Matternes added more details and finer shading to his next iteration (below) of the full mural sketch in preparation for a full-color rendering. In some cases, he made corrections on sheets that could be overlaid, such as his addition of windblown loess and patterned ground to the distant landscape, at top. Note that humans are not yet included in these sketches.