GREAT PLAINS GRASSLAND

Middle-Late Miocene

Clarendonian Land Mammal Age, 12.5 to 9.4 million years ago

During the middle and late Miocene, many North American landscapes became drier and more open, especially across the Great Plains. These environments were similar to the short-grass prairies of today, and large mammals that lived in herds thrived here. This broad transition, from forests to savannahs to grasslands, was happening on a global scale, too, as changes in ocean circulation made Earth’s climate cooler and drier, but associated changes in plant and animal communities took place at varied times on different continents.

In North America, one such evolutionary transition occurred among the hoofed mammals, or ungulates. For tens of millions of years, odd-toed ungulates (perissodactyls), such as tapirs, horses, and rhinos, had been more diverse than their even-toed counterparts (artiodactyls), such as pronghorn, deer, cows, and camels. By the middle of the Miocene, the tables had begun to turn, with the artiodactyls becoming increasingly diverse—a trend that has continued to the present day. Artiodactyls now enjoy a 10:1 dominance in species over their perissodactyl kin. The small number of horse, rhino, and tapir species alive today is a product of this long-term decline in fortunes.

In the middle and late Miocene, North America was home to many mammal groups that we now consider exotic. Elephants had started to migrate from Asia across the Bering land bridge in the early Miocene; in the late Miocene, they spread across the continent and diversified as well. The shovel-tusked gomphothere Torynobelodon was a striking example of one such new species. Multiple contemporary species of camels, rhinos, and horses lived alongside them.

Evidence for the Ancient World

The best-known North American fossils from the middle and late Miocene have been found in the Great Plains of the United States, as well as Texas, California, and Florida. The Valentine and Ash Hollow formations in Nebraska are especially productive geologic strata, preserving thousands of fossil mammal remains. These beds are part of the larger Ogallala Group, a broad belt of sediments that were laid down across the Great Plains in ancient river systems as the Rocky Mountains were uplifting in the presence of heightened volcanic activity in Idaho.

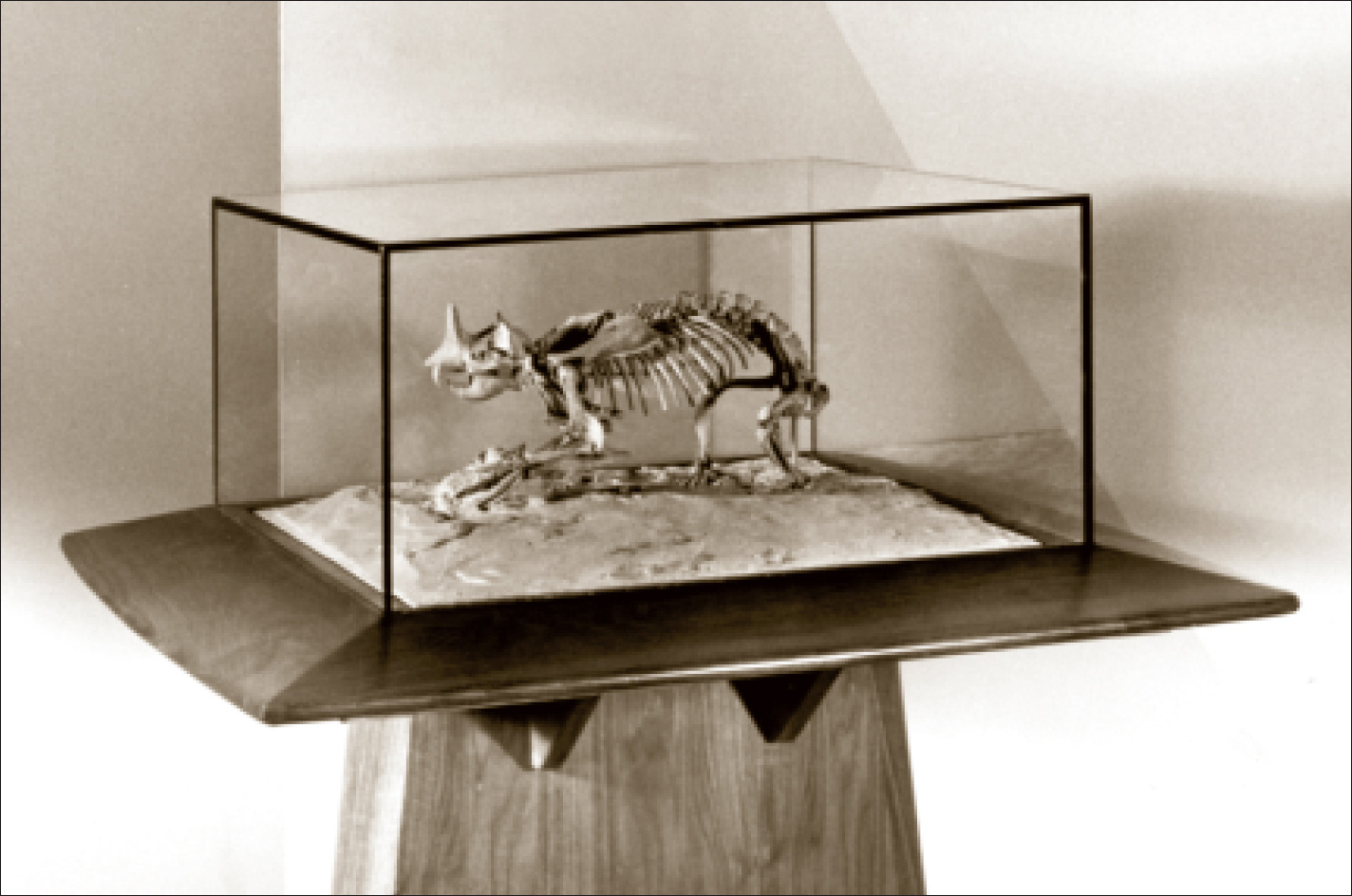

Skeleton of the hippo-like rhinoceros Teleoceras in its 1960s-era exhibit case in The Age of Mammals in North America. The skeleton was later shown in the Mammals in the Limelight exhibit (see photo at right).

Local collectors were the first to obtain fossils from the Ogallala outcrops, in the late 19th century. They were followed by East Coast collectors such as John Bell Hatcher, a famous collector for Yale’s Othniel Marsh, who uncovered thousands of bones of the rhino Teleoceras near Long Island, Kansas. Later, crews working for Childs Frick at the AMNH began to prospect in this region as well, including collector (and later curator) Morris Skinner. Over several decades, they amassed tens of thousands of mammal fossils. Important collections are also housed at the University of Nebraska State Museum and the Denver Museum of Nature and Science.

Within the Ash Hollow Formation, the Ashfall beds of northeastern Nebraska are among the most famous and productive. About 12 million years ago, the Bruneau-Jarbridge eruption in Idaho—then located over the Yellowstone hotspot—deposited many feet of volcanic ash across the Great Plains. Over several weeks, this ash poisoned and buried animals across the region, thousands of which were eventually preserved as fossils. At the Poison Ivy Quarry, the skeletons of hundreds of individuals of the rhinoceros Teleoceras, including a pregnant cow, have been found in addition to many species of camels, horses, dogs, turtles, and birds. Their remains are exquisitely preserved, some of them still showing evidence of the bone damage caused by lung disease brought on by living their final weeks under the Bruneau-Jarbridge ash cloud.

Discovered in 1971 by paleontologist Michael Voorhies, the Poison Ivy Quarry since then has been excavated continually under the auspices of the University of Nebraska State Museum. Its amazing richness led to the creation of Ashfall Fossil Beds State Historical Park in 1991; it is now also a National Natural Landmark. The remnants of the volcanic eruptions responsible for Ashfall’s formation were themselves set aside in 1924 as the Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve, in central Idaho.

Skeleton of the horned rodent Ceratogaulus as it appeared in the Age of Mammals in North America exhibit, late 1960s. Its large hands and feet and prominent elbows all point to strong digging abilities.

The mural as featured in the late Miocene display Grazers’ Day of Glory in the Mammals in the Limelight exhibit, around 1988. Note the skeletons of Teleoceras at left and Stegomastodon at right.

The Creation and Context of the Mural

This was the last mural of the original four that the Smithsonian commissioned. Matternes began his research in 1959, using a list of taxa complied by curator C. Lewis Gazin. The mural was intended to spotlight the mammal faunas of the Clarendonian Land Mammal Age, an interval from 12.5 to 9.4 million years ago—then placed in the early part of the Pliocene Epoch, but now considered to be middle to late Miocene. Matternes also consulted with paleobotanists Maxim Elias of the University of Nebraska and Erling Dorf of Princeton University to develop the plant community. He set the scene under a turbulent sky, using the cloud shadows and attendant highlights to heighten the drama of the scene, much in the manner of traditional chiaroscuro. He completed the mural in 1964.

Although the Ashfall beds were excavated after the mural and exhibit were installed, the Smithsonian collection included a number of the same species found there, including Teleoceras (from Hatcher’s Kansas excavations), Synthetoceras, and the horned rodent Ceratogaulus, which were exhibited with the mural. The museum also incorporated specimens from slightly older (Barstovian Land Mammal Age) and younger (early Pliocene) deposits in the display, including the gomphothere elephant Stegomastodon.

Upon its completion, this mural and its associated specimens concluded the story of mammal evolution in the Cenozoic Era as told in the Smithsonian’s original fossil mammal exhibit, The Age of Mammals in North America. The epoch’s open grasslands, which Matternes rendered in orange and brown, were starkly different from the lush, dark green forests of the early–middle Eocene (see this page) that marked the story’s beginning. By 1964, visitors could immerse themselves in four distinct ancient environments representing more than 40 million years of mammalian evolution.