Bridger Formation, Wyoming

Painted 1960

Acrylic on canvas; 12 ft., 1 in. H × 18 ft., 2 in. W

Bridger Formation, Wyoming

Painted 1960

Acrylic on canvas; 12 ft., 1 in. H × 18 ft., 2 in. W

Bridgerian Land Mammal Age, 50.3 to 46.2 million years ago

1 · Platanus (sycamore)

2 · Sapindus (soapberry)

3 · Lygodium (climbing fern)

4 · Macginitiea (fan-leaf sycamore)

5 · Uintatherium (uintathere)

6 · Onoclea (sensitive fern)

7 · Palmacites (fan palm)

8 · Palaeosyops (brontothere)

9 · Liquidambar (sweetgum)

10 · Sciuravus (rodent)

11 · Smilodectes (primate)

12 · Hyrachyus eximius (early perissodactyl)

13 · Trogosus grangeri (tillodont)

14 · Pseudotomus (rodent)

15 · Stylinodon mirus (taeniodont)

16 · Helaletes (tapir)

17 · Patriofelis ferox (catlike creodont)

18 · Homacodon (early artiodactyl)

19 · Orohippus (four-toed horse)

20 · Helohyus (early artiodactyl)

21 · Sagittaria (arrowhead plant)

22 · Hyopsodus (condylarth)

23 · Mesonyx (condylarth)

24 · Metacheiromys (palaeanodont)

25 · Machaeroides eothen (saber-toothed creodont)

26 · Osmunda (royal fern)

27 · Sinopa grangeri (hyaenodont)

28 · Saniwa (monitor lizard)

29 · Echmatemys (freshwater turtle)

30 · Eichhornia (water hyacinth)

31 · Nymphaea (water lily)

32 · Crocodilus (crocodile)

Matternes’s fondness for the faces and feet of mammals is evident throughout the murals. Here Hyrachyus works its way through the undergrowth, clearly displaying feet with a central main digit—typical of perissodactyls (odd-toed ungulates). Although superficially horselike, it was more closely related to tapirs and rhinos.

These studies of the early horse Orohippus show a dynamic range of poses and facial expressions. Note again how the feet are shown from many different angles. In the final mural, Matternes used some of these sketches to develop his depiction of a different species, the tapir Helaletes.

Specimens from the Fossil Butte lakebeds record a subtropical world full of palms, elephant ear plants, and large broadleaf trees. One common fossil is Macginitiea (right and opposite top left), an extinct sycamore relative with fan-shaped leaves named after Berkeley paleobotanist Harry MacGinitie. Another abundant fossil is the four-lobed fern Lygodium (opposite right), still alive today as a tropical vine that frequently wraps around tree trunks. Matternes decorated the banks of the pond with arrowhead plant (Sagittaria; opposite, lower left), water lily (Nymphaea), and water hyacinth (Eichhornia), but he based these depictions on living plants from similar environments rather than actual fossils from the Fossil Butte site.

The knobby, tusked head of Uintatherium recalls those of rhinos and hippos, but the species was part of a distinct early lineage of giant herbivorous mammals. Starting with studies of fossil skeletons (see this page), Matternes developed this evocative image of the beast in life. An earlier sketch (opposite) is in some ways even more expressive.

Matternes’s drawing of Uintatherium, based on the Smithsonian mounted skeleton, provided important details for his fleshed-out reconstructions (see this page).

Machaeroides, seen snarling below, was not a cat but a creodont, an archaic carnivorous mammal. Here this early saber-toothed predator pins its prey, the monitor lizard Saniwa. Their struggle is documented in the surrounding footprints—yet another means for the artist to bring feet to the fore. He sketched the feet of each of these two species in advance; his drawing of Saniwa’s prints is shown at right.

The final versions of Orohippus below differ significantly in their poses from Matternes’s earlier sketches (see this page) but retain their distinctive expression. A footprint sketch (right) matches the painting, however, showing the four front toes and three hind toes typical of these early horses.

Easily recognizable by its lemurlike appearance, the primate Smilodectes browses for leaves in sweetgum trees at right. An earlier sketch (below) shows a dozing individual. Smilodectes was one of several primate species to live in the United States at this time. Primates disappeared from the United States as the climate cooled and subtropical forests retreated in the late Eocene.

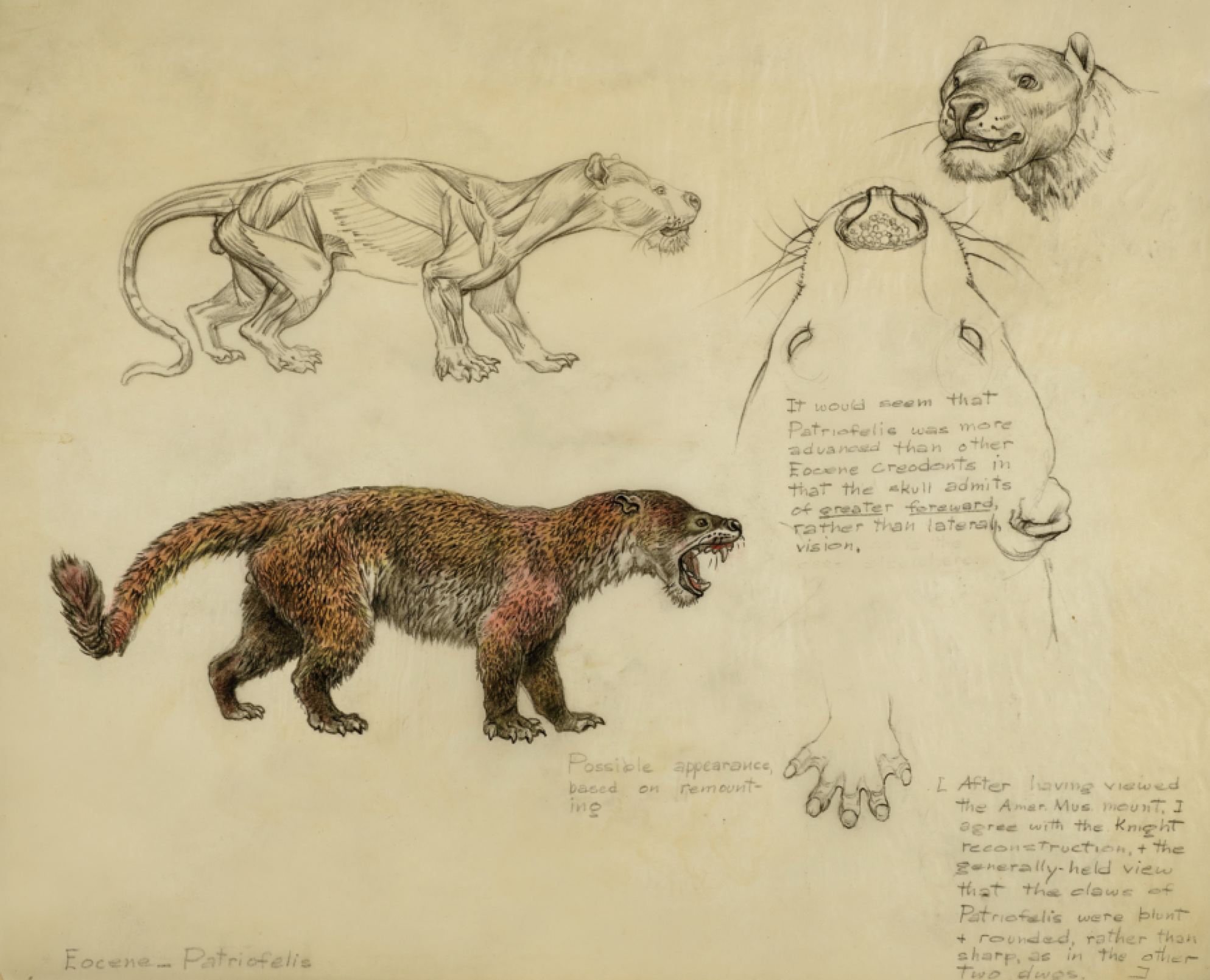

Patriofelis was a pumalike carnivore—but again, not a cat—with a broad snout, forward-facing eyes, and blunt, nonretractable claws. Like Machaeroides (see this page), it was a creodont, which evolved prior to the advent of familiar modern carnivorous mammals. In portraying this individual stalking its prey, the artist was careful to reveal the detailed underside of its right front paw.

The important anatomical details of Patriofelis are noted here by Matternes, along with full-body muscle and life restorations. The latter is distinctly shaggier than the final mural version, and less pumalike.

The early brontothere Palaeosyops ambles through a fern-filled clearing, as the rodent Sciuravus climbs a branch in the foreground. Brontotheres evolved immense sizes within a few million years (compare with Megacerops, this page), but in the early Eocene, they were still only the size of tapirs (which are not especially small!). The carefully detailed foot and pads (right; see also this page) show the dominant third toe, typical of perissodactyls.

Rodents diversified into many types during the Eocene. Two very different species are shown in the mural as climbing, somewhat squirrel-like forms. Sciuravus (above) was small and gracile; Matternes drew its fur as remarkably plush. Pseudotomus, shown in the other three sketches, was much larger and more robust. It may have dug more often than it climbed.

Strange Stylinodon belonged to a group of early placental mammals called taeniodonts. Its buck-toothed incisors and canines and ever-growing molars were well suited to its diet of tough roots and tubers.

Large, flattened claws, strong limbs, and powerful elbows indicate that Stylinodon was a proficient digger. It was about the size of a large pig.

Eocene crocodilians are known from several well-preserved specimens, indicating animals similar to modern forms. In this unusual set of life poses, color has been applied to the reverse of the page (top) so it appears “beneath” the crocodile’s skin texturing (bottom).

The facial features of the early odd-toed ungulate Hyopsodus are delicately rendered here. New research suggests it was a burrower with some ability to echolocate, an ability that today’s shrews and tenrecs (small, unusual mammals endemic to Madagascar) also possess.

The tillodont Trogosus shared some similarities with Stylinodon (see this page) that suggest it had a diet of tough vegetation, including roots. It had chisel-shaped incisors, strong jaws, and curved claws. Weighing up to 300 pounds, its bearlike appearance is especially vivid in these postural sketches (opposite top).

With limbs adapted for digging and reduced teeth, Metacheiromys may have been similar to today’s anteaters, and it was distantly related to pangolins. Matternes restored it along these lines in this early sketch (right) but eventually opted for a more mongooselike version in the final mural. It belongs to a group called palaeanodonts, whose affinities are still debated.

This sketch (above) reflects an early design idea in which related animals would be grouped together in front of different backgrounds. Compare this with the more naturalistic presentation of the preliminary painting (opposite), which mixes different animals together. This was the final version before he created the full-sized mural.