Chadron Formation, South Dakota and Nebraska

Painted 1962

Acrylic on canvas; 12 ft., 2 in. H × 22 ft. W

Chadron Formation, South Dakota and Nebraska

Painted 1962

Acrylic on canvas; 12 ft., 2 in. H × 22 ft. W

Chadronian Land Mammal Age, 38.0 to 33.9 million years ago

1 · Populus (poplar)

2 · Ailanthus (tree of heaven)

3 · Salix (willow)

4 · Megacerops coloradensis (Brontotherium; brontothere)

5 · Subhyracodon (hornless rhinoceros)

6 · Trigonias (hornless rhinoceros)

7 · Perchoerus (peccary)

8 · Hyracodon (rhinoceros)

9 · Oreopanax (aralia)

10 · Protapirus (tapir)

11 · Mesohippus (three-toed horse)

12 · Archaeotherium zygomaticus (entelodont)

13 · Merycoidodon (oreodont)

14 · Poebrotherium (camel)

15 · Helodermoides tuberculatus (glyptosaurine lizard)

16 · Hyaenodon horridus (hyaenodont)

17 · Protoceras (protoceratid)

18 · Hypisodus minimus (hypertragulid)

19 · Hoplophoneus (false saber-toothed cat)

20 · Bothriodon (anthracothere)

21 · Hesperocyon (dog)

22 · Ischyromys (rodent)

23 · Palaeolagus (rabbit)

24 · Leptictis (Ictops; placental mammal)

25 · Mahonia (Oregon grape)

26 · Leptomeryx (artiodactyl)

27 · Hypertragulus (hypertragulid)

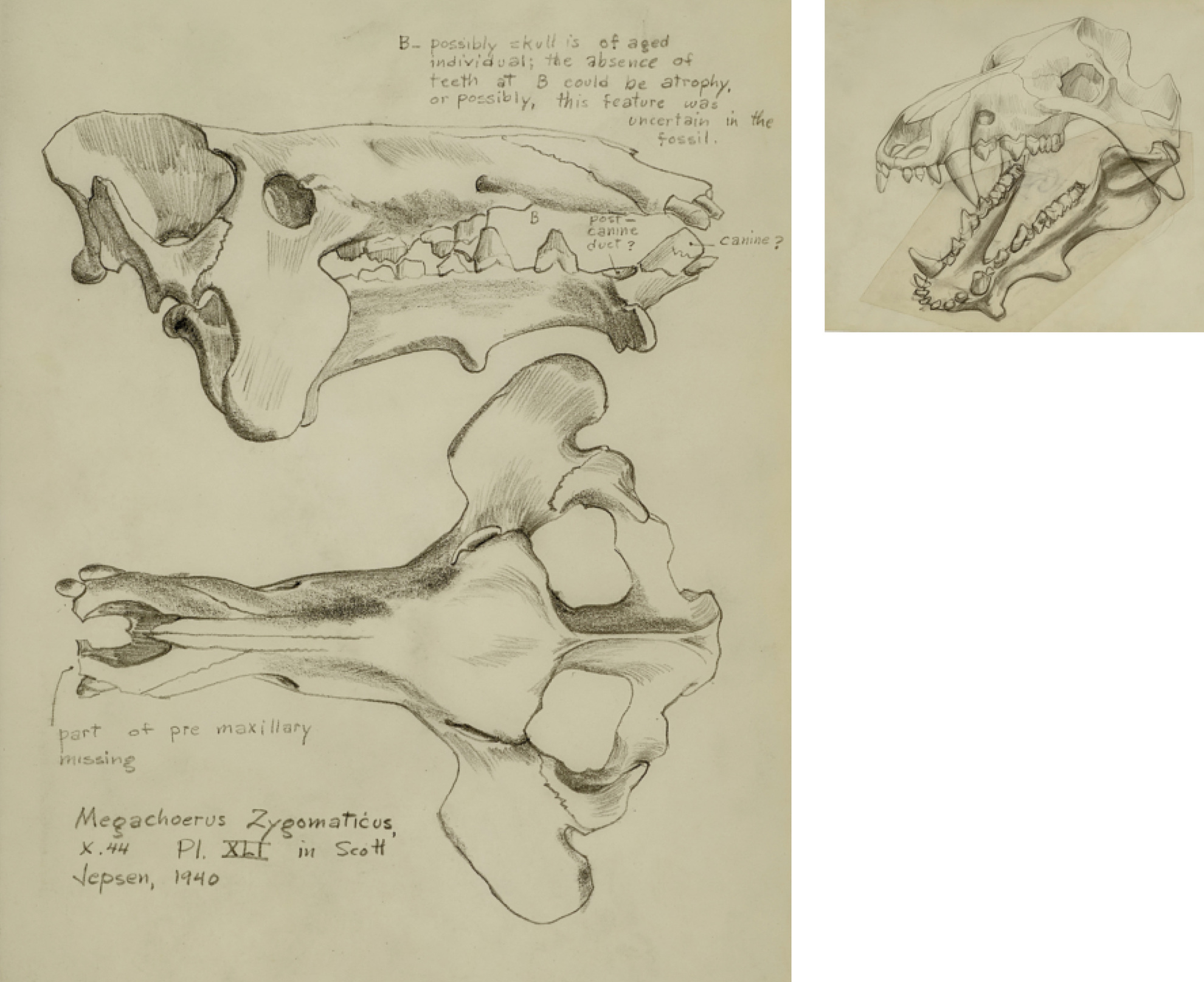

Like other entelodonts (see this page), Archaeotherium zygomaticus (called Megachoerus when Matternes painted this mural) had a huge, bumpy skull and prominent fangs. It was about the size of a grizzly bear and was omnivorous, dining on live prey and carrion as well as roots and tubers. Although quite hoglike in many ways, entelodonts were not closely related to pigs.

The remarkable skull of Archaeotherium zygomaticus, with its broad jaw flanges, is beautifully shown in the shaded sketch at left. The three-quarters view (above) highlights its bony protuberances.

Early peccary Perchoerus (below) stands alongside a recumbent hornless rhinoceros known as Trigonias. This peccary remains a relatively rare fossil, with no complete skeletons known even today. Matternes made his “first attempt to restore Perchoerus” (right), as he wrote on the sketch, by modifying the skeleton of the Pliocene/Pleistocene peccary Platygonus (see this page).

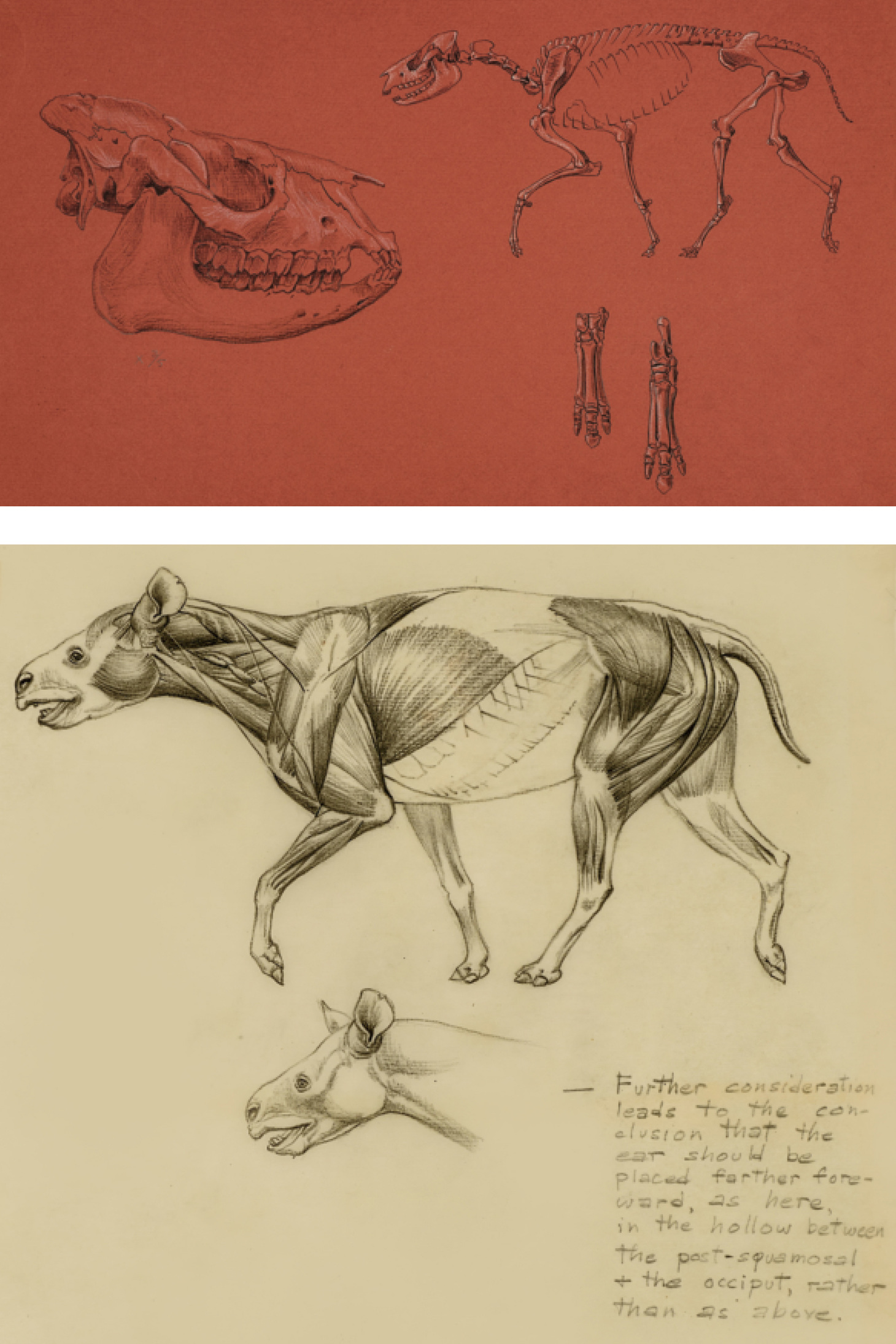

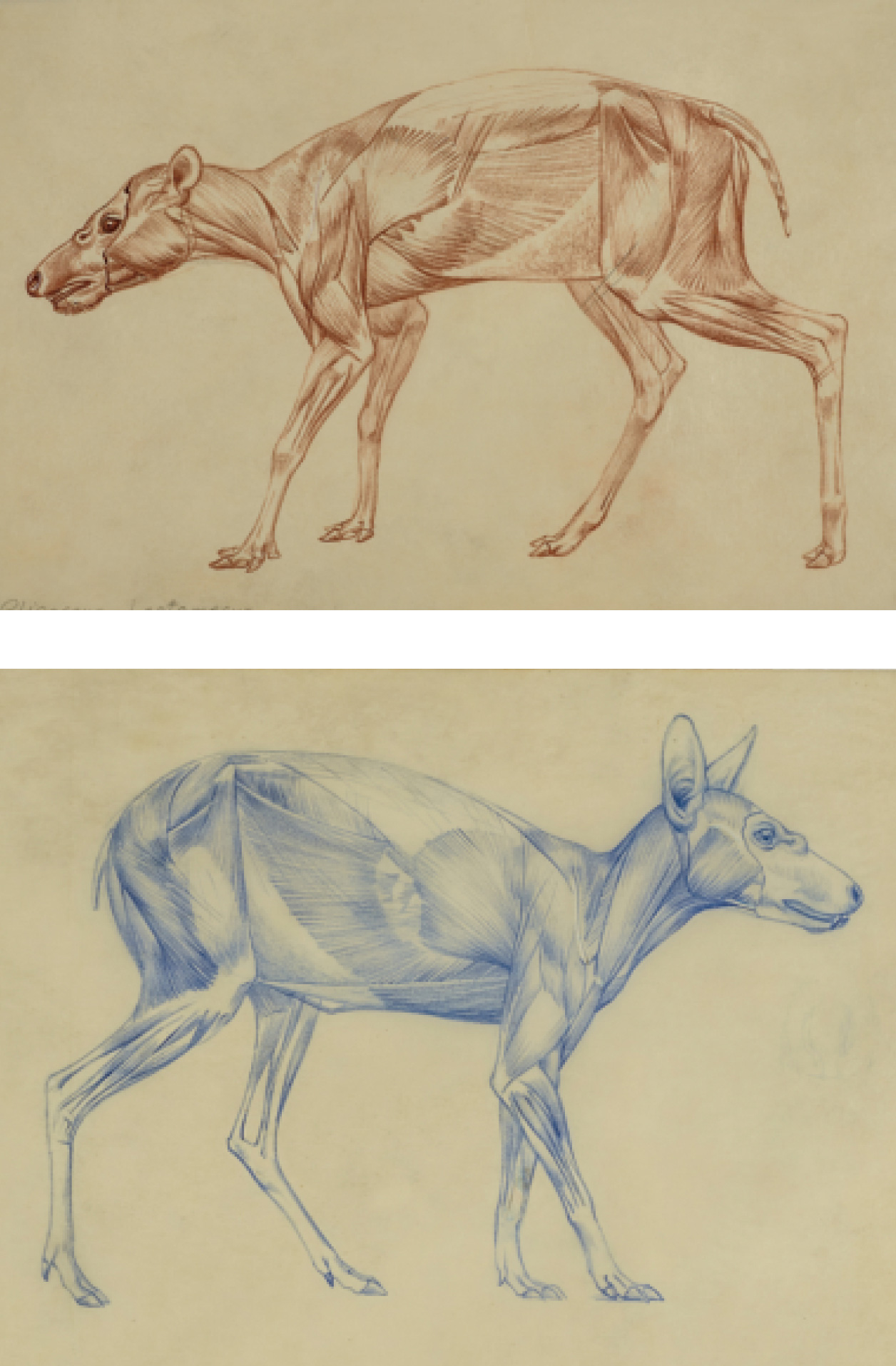

Trigonias is known from dozens of skeletons, which allowed Matternes great accuracy in the animal’s proportions. He sketched the musculature as an overlay to the skeleton (bottom). Modern rhinos have a nose horn, but Trigonias’s skull (top) suggests it had no horn of any kind.

Hyracodon was an early rhinoceros that bore little resemblance to its familiar modern relatives. Long-legged and slender, it looked more like a small horse than a living rhino. Its three-toed feet—clearly shown in the right-hand individual below—indicate that it was an odd-toed ungulate, or perissodactyl. The gridded sketch (right) was made in preparation for the final wall painting.

As he did with most species, Matternes drew the skeleton and musculature of Hyracodon first, before he made the mural. He gave serious thought to details such as ear placement (left). His use of white on red (top) nicely highlights the animal’s bone structure.

Matternes often painted small shrubs in the foreground of his landscape scenes that exemplified an area’s flora. Here a small Oregon grape (Mahonia) shrub is shown with its characteristic thorny leaves.

The artist first sketched the small lagomorph mammal Palaeolagus as quite rabbitlike (top left), but ultimately he decided to show it as having pika-like short ears (above).

The early camel Poebrotherium was small and graceful, and probably lived much as deer do today, browsing in a variety of environments. The beautiful coloration and evocative behavior envisioned by Matternes make Poebrotherium one of the more striking mammals in this mural.

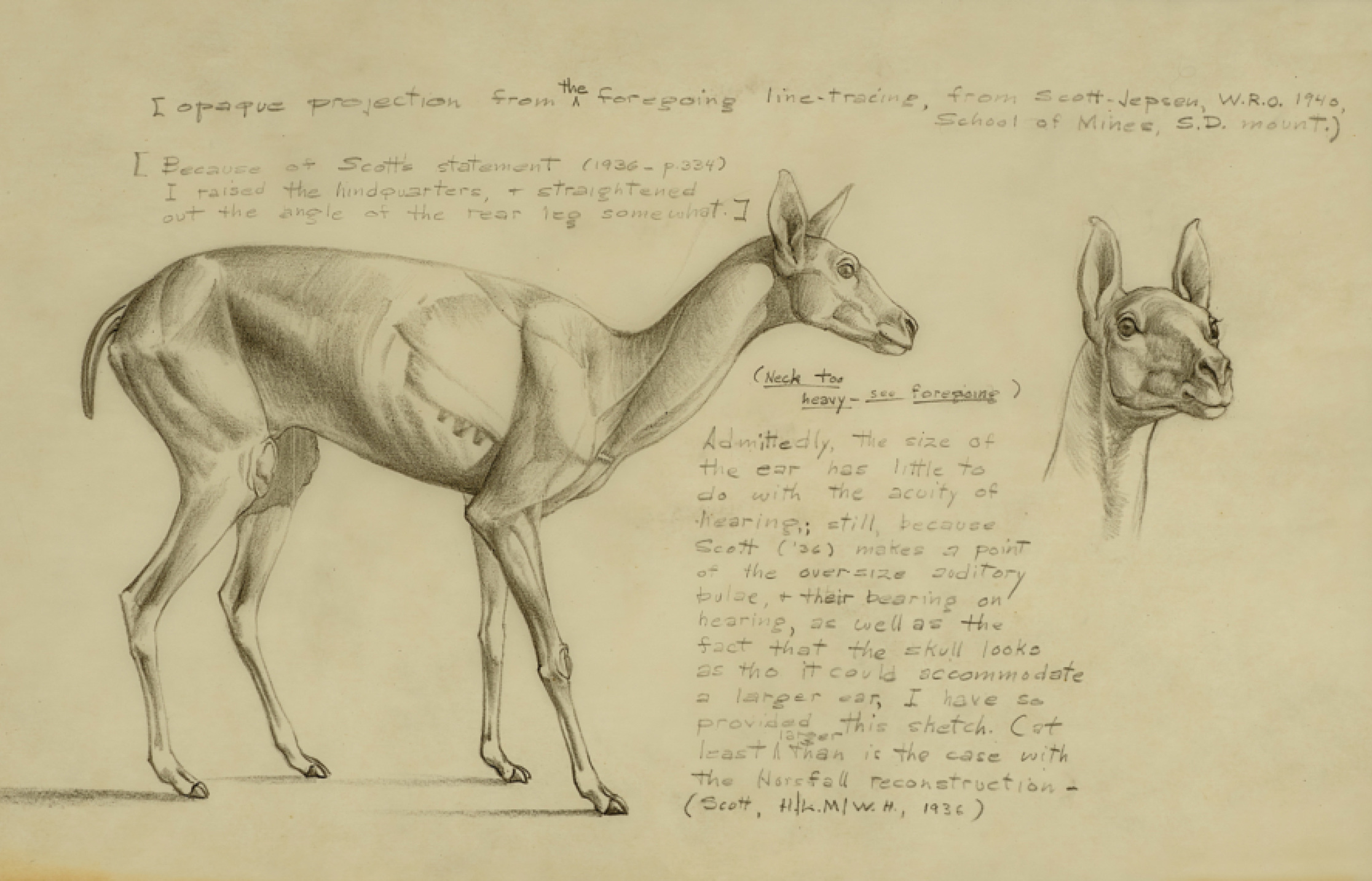

This sketch of Poebrotherium displays many of Matternes’s hallmarks: detailed notes, a lengthy consideration of ear position, gently shaded musculature, and an oblique view of the animal’s face and snout.

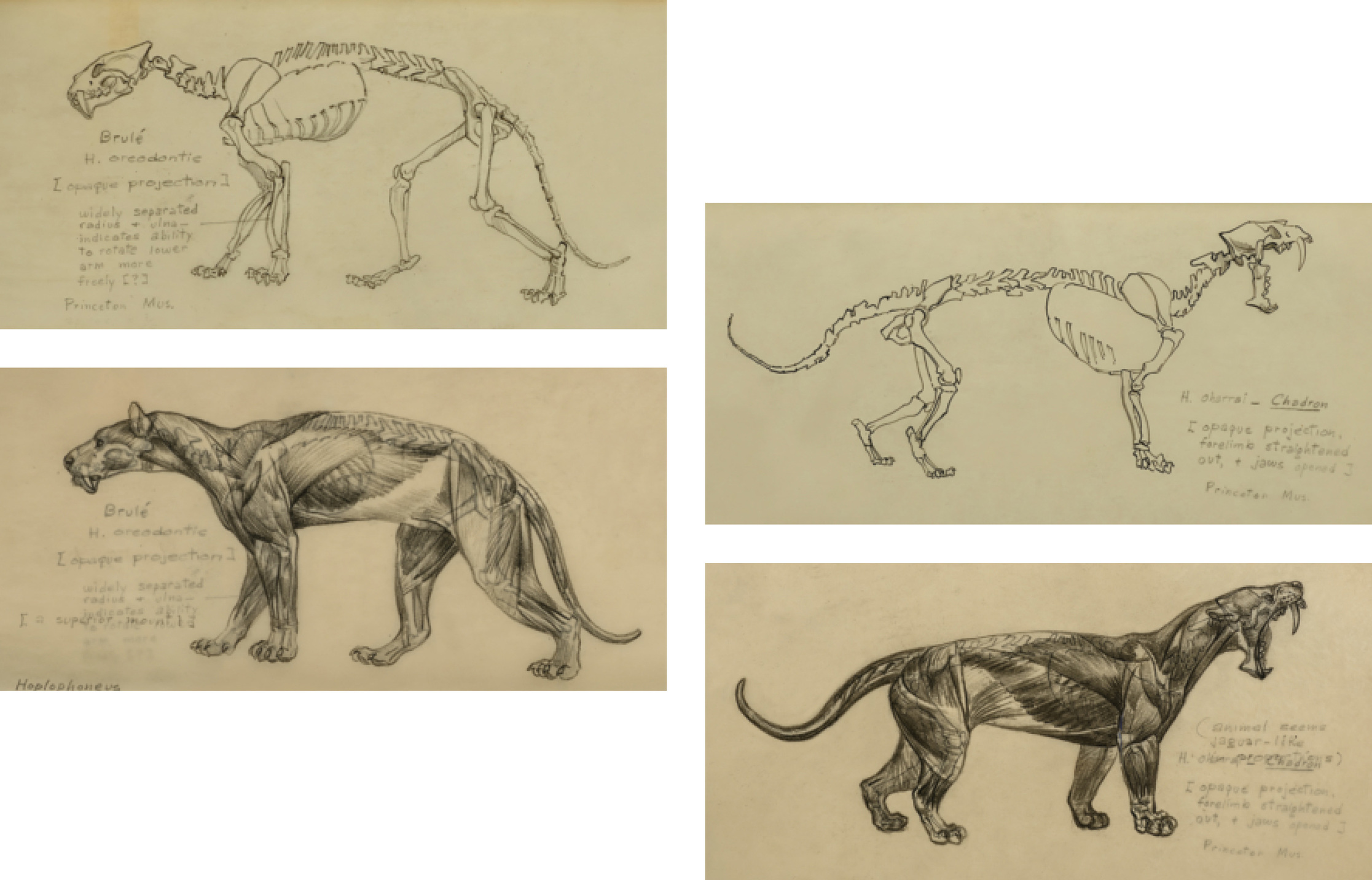

The “false” saber-toothed cat, Hoplophoneus, was not a true cat but did indeed bear lethally long canines. It represents an early evolution of saber teeth among carnivorous mammals (compare it to the later, independently evolved species shown on this page, this page, and 169). The pattern and texture of the animal’s fur appear distinctly feline, but Hoplophoneus had only distant affinities with cats.

Two different species of Hoplophoneus are shown for comparison in these muscle-skeleton overlays: the older, stockier H. oharrai (now called H. mentalis; right column) and the younger, more slender H. oreodontis (left column).

In the image below, two tiny hoofed mammals (Leptomeryx, left, and Hypertragulus, right) meet beneath a shrub, unaware that Hoplophoneus (out of frame to upper left) has taken an interest in them. Both species were ruminants, like modern cows and camels, but they belonged to now-extinct lineages. They may have been somewhat similar to living musk deer and chevrotains (mouse deer) in their habits.

Matternes used opaque projections to enlarge published images and create these colored-pencil sketches of the skeletons and musculatures of Leptomeryx (top row) and Hypertragulus (bottom row).

Matternes speculated that Hypertragulus bore a scent gland in the pit in front of its eye; this can be seen in both his restoration sketch (bottom right) and the detail from the finished mural shown opposite.

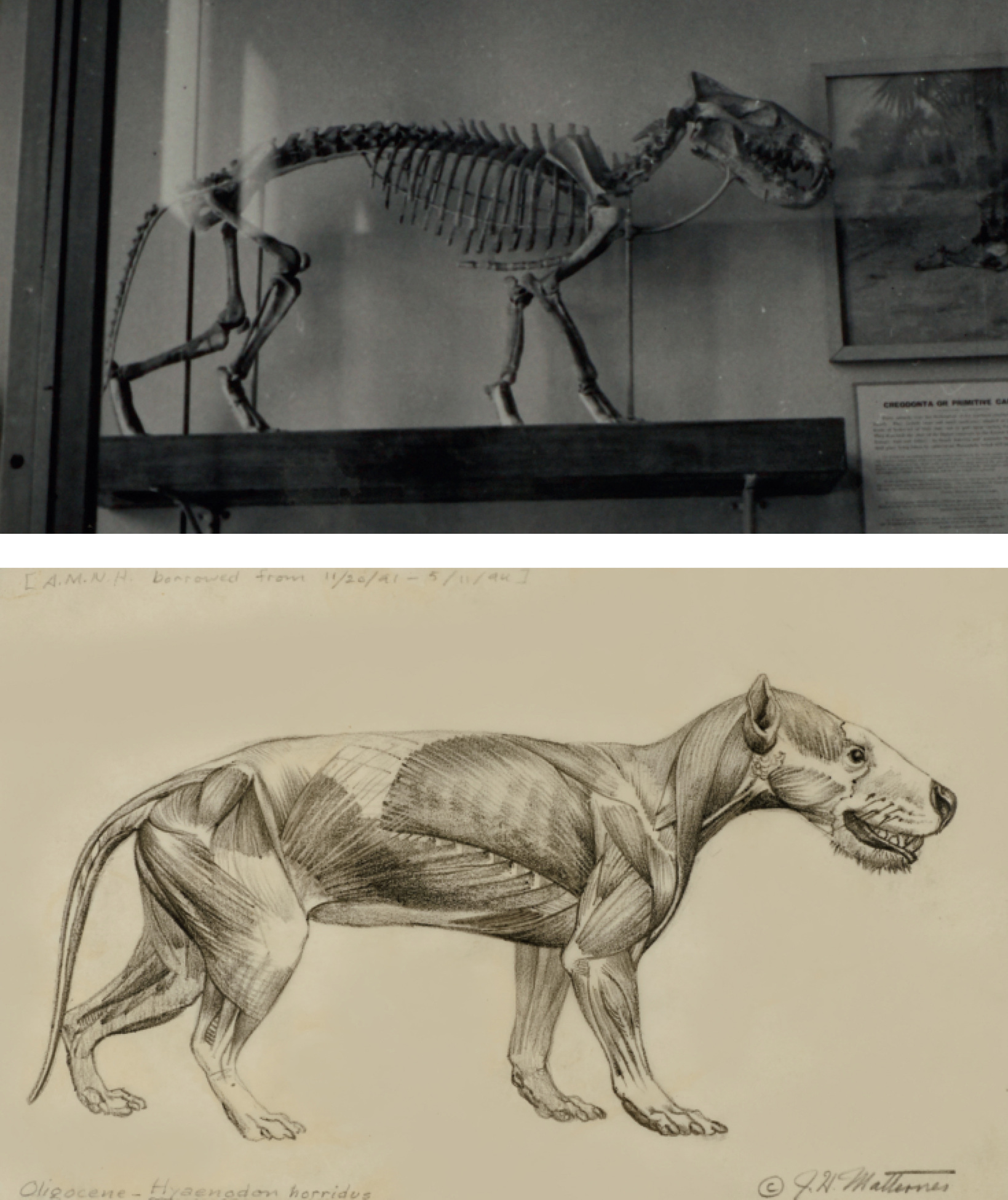

The pebbly skin-armor of the lizard Helodermoides (below) afforded little protection against the jaws of Hyaenodon (right). Hyaenodon was one of the largest carnivores of its time, weighing as much as a gray wolf (about 100 pounds). Superficially doglike, it belonged to a now-extinct mammal family.

Matternes used his own photography of the mounted skeleton of Hyaenodon horridus at the American Museum of Natural History (top) as the basis for his full-body muscle reconstruction (below).

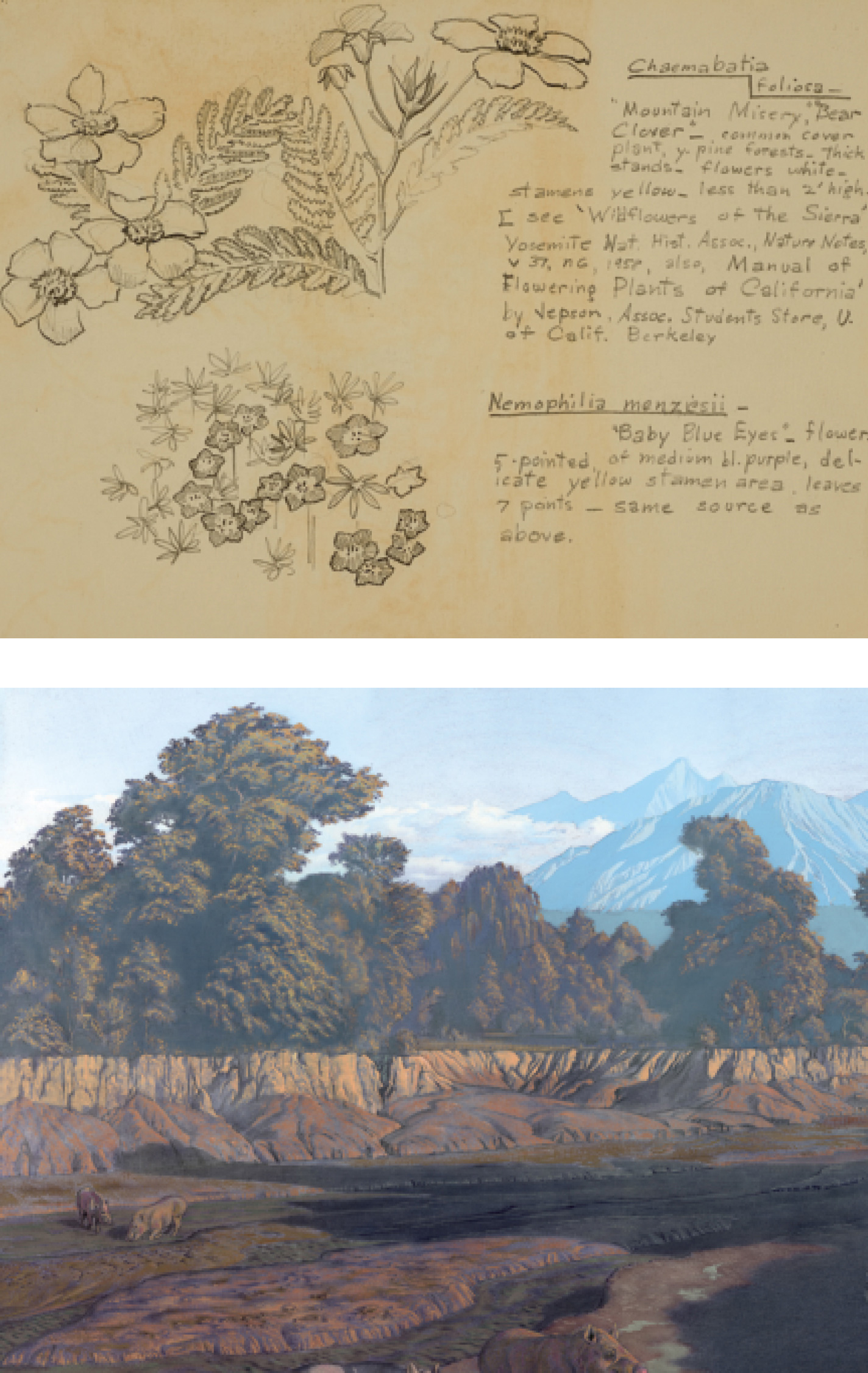

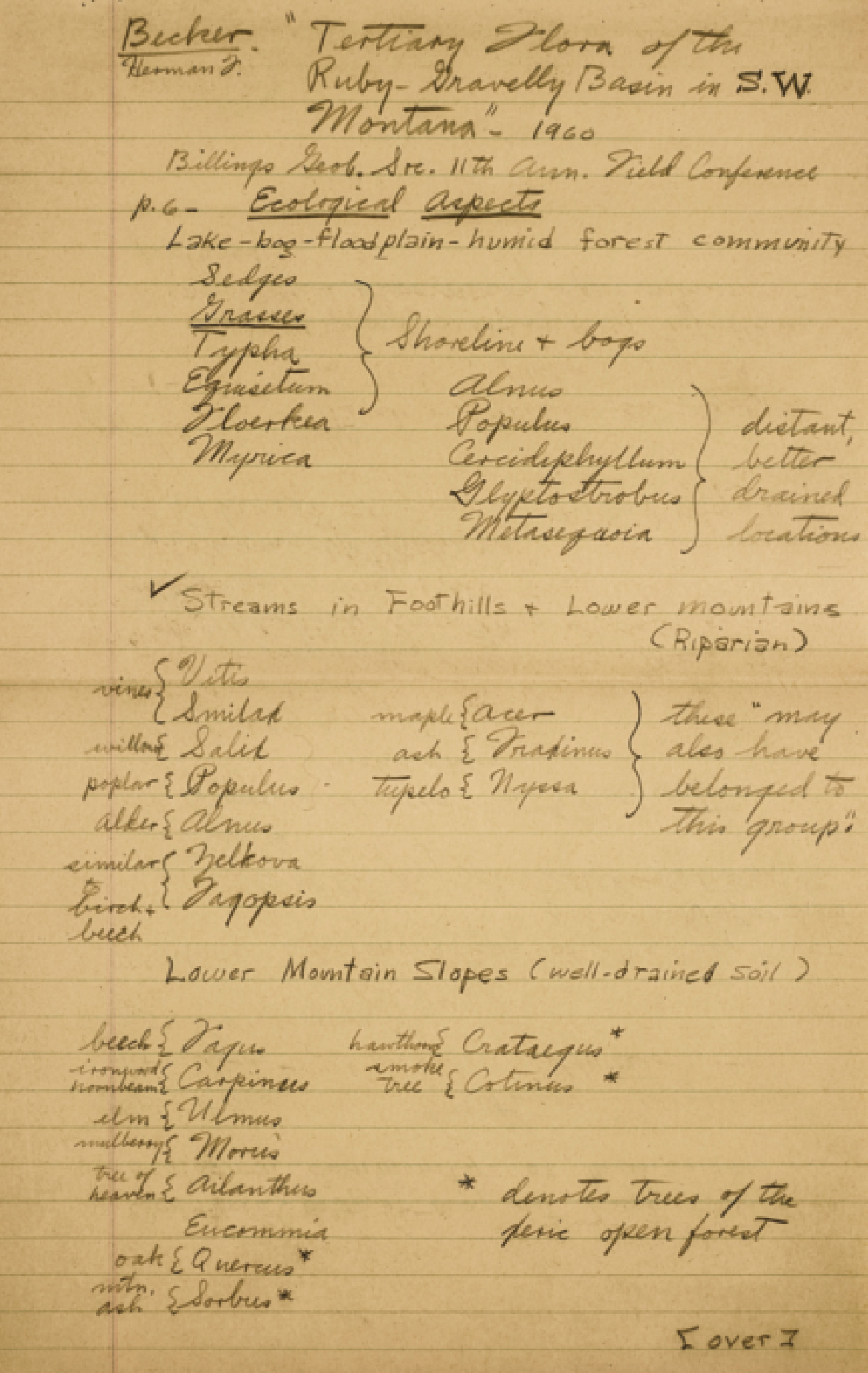

Matternes based the landforms of the mural’s seasonally dry riverbed (above), which serves as a sort of stage for several of the animals, on his studies of similar modern settings (see this page). The artist derived many of his depictions of the vegetation from his consultations with Herman Becker of the New York Botanical Garden, who had studied the late Eocene floras of western Montana.

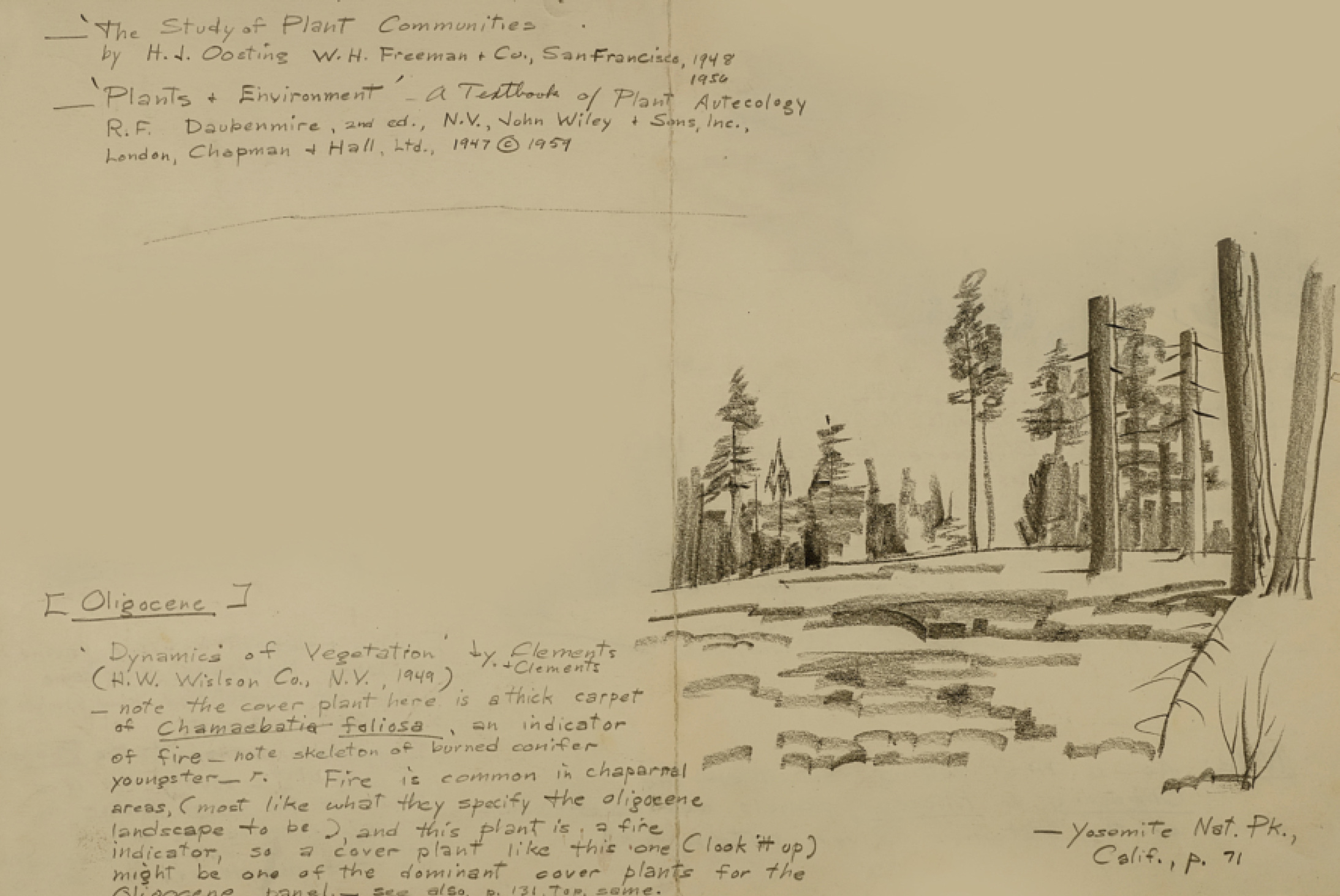

Matternes’s vegetative landscapes were based on lists of species that he obtained from paleobotanists (above). Because most of the plants he depicted in the mural are genera still alive today, he was able to draw them from living examples (top left).

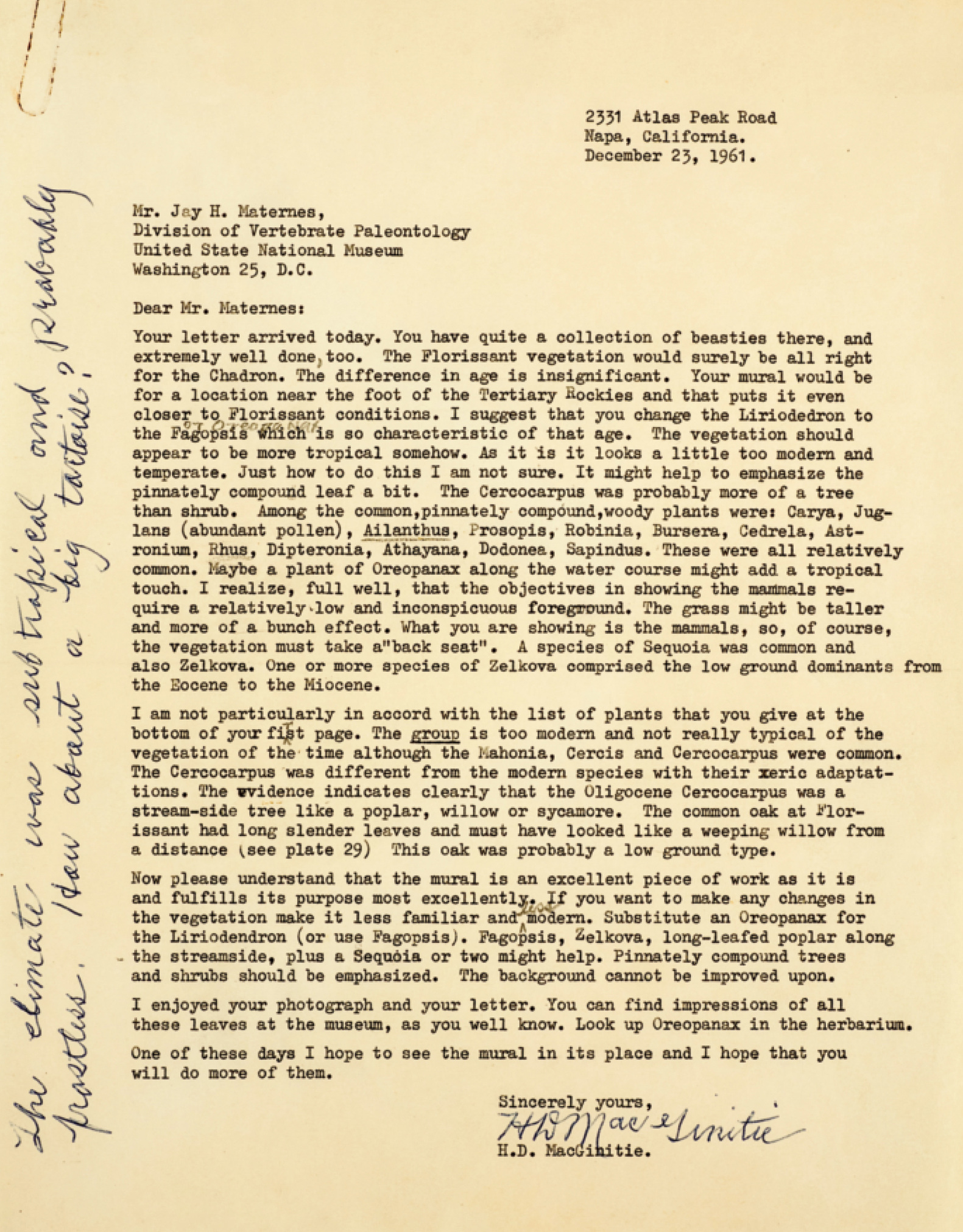

This 1961 letter from Berkeley paleobotanist Harry MacGinitie to Matternes shows their collegial efforts to make the murals as accurate as possible, given the limited nature of the plant fossil record from the White River beds.

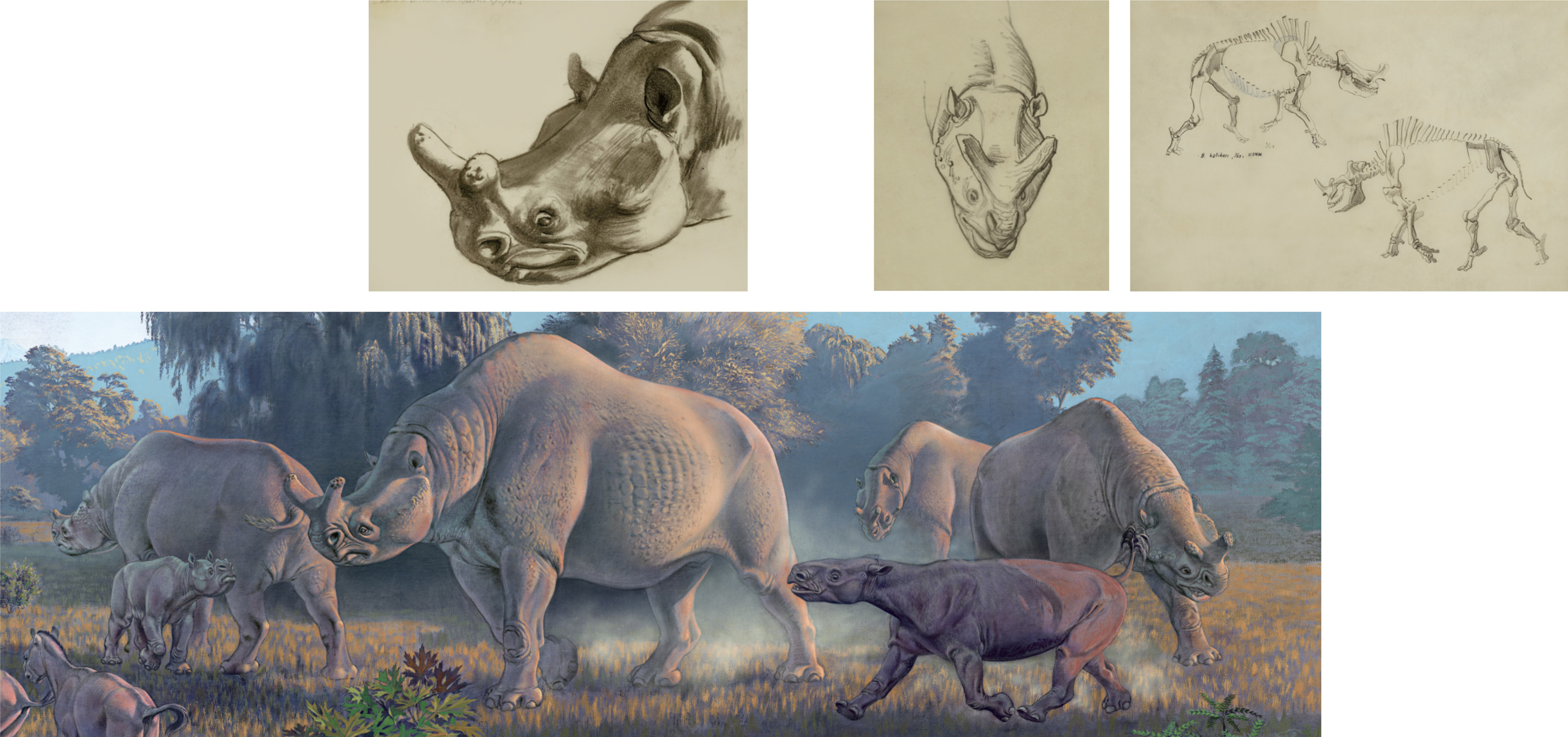

Brontotheres (or titanotheres) were some of the largest mammals of their time and were characterized by prominent, often forked nose horns (right). Although they bore a strong resemblance to modern rhinos, they were only distantly related to them. This herd of Megacerops (called Brontotherium at the time) guards a calf from outsiders, below.

The Smithsonian’s Megacerops skeleton, still on exhibit in the same pose that Matternes sketched here (see this page), was an important reference for the artist (above right). Various angles show the geometry of its bizarre nose horns (opposite top and above left).

In these sketches, Matternes worked to integrate information from both paleobotany and the modern world (including the work of early forest ecologists) to create plausible ancient landscapes. Note that “Oligocene” and “Pliocene” in his notes here refer to the late Eocene and middle–late Miocene murals, respectively.

This is a Matternes sketch of Yosemite National Park. Although the redwood is now largely restricted to the West Coast, it would have been reasonable for Matternes to include it in this mural because fossil redwoods had been found in Colorado’s Florissant Fossil Beds. In the end, however, he did not include the iconic tree in this scene.

The preliminary painting incorporated changes from the shaded sketch (indicated in the tracing-paper overlay, top) and showed all important aspects of appearance, layout, and color. Nonetheless, it differed from the final mural in small details, such as the tail of Trigonias and the number of Hypertragulus individuals.

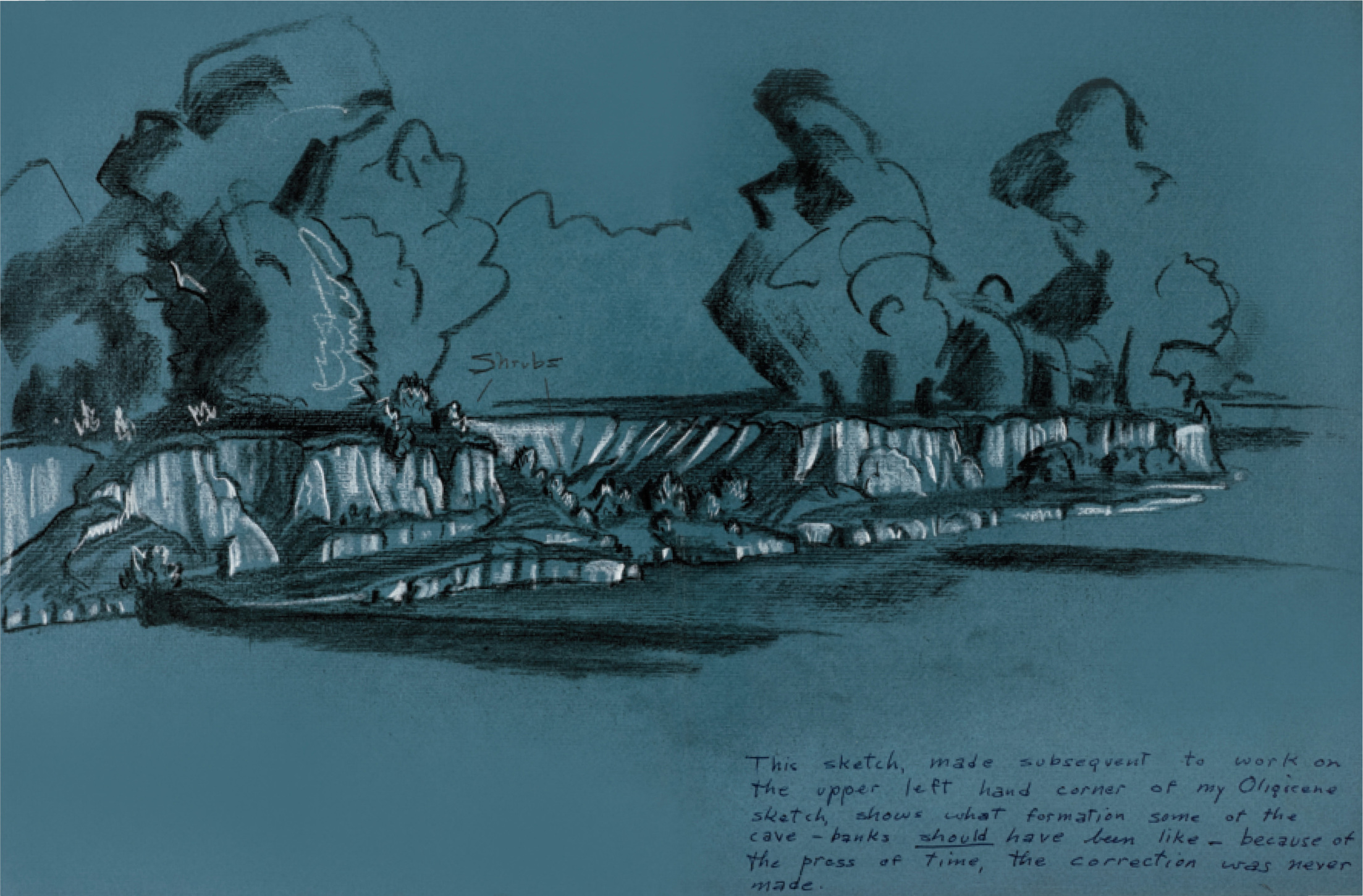

This dramatic black-and-white-on-blue sketch shows the intended appearance of the riverbanks in the upper left quadrant of the mural. This plan was never implemented “because of the press of time,” as Matternes notes on the sketch.