3

Brewing Pilsener Beers—Materials and Equipment

What are the specific ingredients and equipment employed in brewing Pilsener? Two points need to be kept in mind: first, this is not a brewing handbook, so many basic steps that would be addressed at length in such a handbook are mentioned here only in passing. Second, my recommendations for materials and methods are not the only ones that will work. I will give you the rationale for my preferences, but you must be the final judge.

INGREDIENTS

Assuming that no mistakes are made during manufacturing, the choice of ingredients largely determines the flavor of the finished beer. It is therefore critical to understand the flavor characteristics that each component imparts. However, factors such as cost, availability, and suitability to the equipment at hand must also be considered.

- Malt -

Barley malt is a most important ingredient in any lager beer, and it is especially critical in Pilseners. Pale malt typically is responsible for 80 to 100 percent of the fermentable matter in a Pilsener wort, and the clean, simple flavor profile of this beer means that its character will be largely determined by the brewer’s choice of this most essential material.

The first choice the American brewer must make is between imported and domestic pale malt. There are good arguments to be made on both sides. Domestic malt is invariably cheaper, owing to lower shipping costs. It is available from numerous sources, which means that shortages are unlikely. This is especially important to a microbrewer who may be faced with increased demand for his product. It is almost always possible to get as much domestic pale malt as needed in a few days’ time. Rapid delivery and the multiplicity of suppliers also means that if problems should arise (e.g., a shipment arrives in bad condition), they can be solved quickly. The quality is almost always good, in my experience. Only once did I get a sample of substandard (grossly undermodified) domestic malt, and this was from a homebrew supply shop that probably had bought malt intended for the food or distilling industry.

The negative side of domestic malts is that they are not quite up to the standard of the best imported malts, in terms of their pure brewing qualities. This is largely because of the barleys from which they are made. Over the last twenty years, breeding programs have improved American six-row barleys enormously, but they still have a higher total nitrogen (and therefore protein) content and considerably more tannin than the two-row barleys that are used on the Continent. The domestic two-row barleys (e.g. Klages) occupy an intermediate position between the American six-row and European two-row types.

If a microbrewer is inclined to favor the imported malts, he must do his utmost to assure himself a steady supply at a reasonable cost. All brewers should consider whether the malt they propose to use will suit their process. For many years, the trend in Europe has been toward using well-modified malts to brew Pilsener-style beers, but the traditional undermodified malt is still made. If you are committed to an infusion mash (a mash carried out in a single vessel), you must be sure that your malt is fully modified. Undermodified malt virtually demands a decoction mash (a mash in which the various temperature rests are accomplished by boiling a portion of the mash in a separate vessel). The best test is simply to chew a few grains to see if you can detect the hard, steely tips of undermodified malt. But specifications also are helpful to know, particularly the fine-grind/coarse-grind extract difference.

Most American microbrewers and homebrewers use domestic malts in their Pilsener beers. There is no doubt that it is possible to brew excellent beer from such malts, despite the theoretical advantage held by the European varieties. For microbrewers, the two-row malt is slightly more expensive than the six-row; for homebrewers, prices are usually the same. You might wish to do trial brews with different malts and see what differences you can detect in the final beers. Microbrewers making this test should either buy the malt precrushed from the malting company or use the roller mill in their own plant. Crushing malt in a small flour mill, as most homebrewers do, pulverizes the husks to some degree and results in a greater extraction of tannins into the wort. Thus, such a mill may possibly exaggerate the differences between six-row and two-row malt. Also, one must not assume that all two-row malts are superior. The way the malt is handled and cured is equally important.

My view of these issues is that six-row barley can make excellent pale malt, despite its inherent disadvantages. However, the high tannin content becomes an increasing liability when the malt is cured at higher temperatures. The tannins oxidize and polymerize during kilning, and dark six-row specialty malts, when used in large proportions (certainly over 33 percent), impart an obvious tannic edge to the finished beer. Since virtually all domestic specialty malts are made from six-row barley, I would be inclined to favor imported malts for brewing dark beers such as Munich Dunkel or Düsseldorfer Alt. Fortunately, dark specialty malts are used only in very small amounts for Pilseners, and the domestic products are quite suitable.

Probably the most useful specialty malt for Pilsener beers is Cara-pils® (a trade mark of Briess Malting Company), which is the same as cara-crystal or dextrin malt and has a high content of dextrins and high-molecular-weight proteins. It enhances the body or “mouthfeel” of a beer and also improves foam stability. It does not affect color, aroma, or flavor. Extract is comparable to six-row pale malt. Enzyme content is nil. Dextrin malt contains a substantial amount of unconverted starch and must be mashed with pale malt. Normally, it is used in amounts ranging from 7 to 15 percent of the grist.

Vienna and Munich malts are basically identical to pale malt but are kilned at higher temperatures. They increase color, with typical domestic Munich malt being about 10 degrees Lovibond. However, their most important contribution is the rich malty aroma and flavor they impart. These properties virtually define the Vienna and Munich beer styles. In Pilseners, high-kilned malts can be used in very small amounts (certainly no more than 5 percent) to enhance the malt character of the beer. Large quantities are not desirable because they darken the beer too much and skew the flavor balance toward the malt.

In my opinion, crystal or caramel malt is a better choice than Munich malt for enhancing the malt qualities of a full-bodied Pilsener beer. Like Cara-pils®, but unlike Munich malt, caramel improves foam stability and mouthfeel. It is available in several grades, ranging in color from 20 to 120 degrees Lovibond, and the lower grades (20 and 40 degrees Lovibond) are most suitable for Pilseners and impart a sweet, mild, caramel smoothness. Higher grades are too dark and strong-flavored for this style. Only small amounts of caramel malt are used in Pilseners, typically 5 percent or less.

The dark roasted malts (chocolate and black patent) scarcely are used in Pilseners; their color is so intense that only tiny amounts can be used in a pale beer. Chocolate and most black malts also impart a strong, sharp, “roasted” flavor that is inappropriate to Pilsener. However, at least one American maltster (Briess Malting Company) has developed a black malt with a mild flavor, suitable for coloring adjustments. This black malt could be added to a Pilsener to darken it slightly without changing its flavor. This might be useful to a microbrewer who wanted to make a well-hopped all-malt beer but found that his customers resisted it because its appearance resembled that of mainstream domestic lagers. The amount needed would be very small—perhaps as little as 1/20 of one percent. Black malt usually is rated at about 520 degrees Lovibond.

One specialty malt that should be mentioned here is chit malt, which is used in certain North German Pilseners. This malt is not readily available in the United States, so the reader should refer to the discussion of raw barley, which is almost the same from a practical standpoint (see below).

Wheat malt is not a traditional component of Pilsener-style beers, but because it has many desirable qualities it is well worth considering. Its high content of complex proteins and glycoproteins greatly enhances foam stability. Wheat malt also contributes to the body or “palate fullness” of the beer. At the same time, because wheat has no husk, its tannin content is very low. Replacing a proportion of pale malt with wheat malt lowers the tannin content of the finished beer. Wheat malt has an undeserved reputation of imparting a strong flavor. In fact, the typical clovelike taste of the Bavarian wheat beers is not a result of the wheat malt but of the special yeast strains used in fermentation. The flavor of wheat malt is actually quite mild and smooth, and thus wheat malt combines some of the most attractive aspects of dextrin malt and adjunct grains. In addition, it has a high extract potential, and the domestic varieties are high in enzymes.

Wheat malt also has some drawbacks. It rapidly produces haze, especially when it is used in large amounts such as in a typical Weizenbier. In smaller proportions—up to 20 percent—it poses few problems as long as an adequate protein rest is given. The most troublesome property of wheat malt is its physical makeup. The kernels are small, hard, and glassy, and must be crushed quite fine. This demands a high-powered mill (or some hard labor on a handmill), and in addition, the mill gap must be reset before each run. To avoid these aggravations, the brewer might find it worthwhile to buy wheat malt in precrushed form.

- Adjuncts -

The only unmalted cereals that are traditionally incorporated into European Pilseners are rice and corn (maize). Both perform a similar function in lightening the body and malt flavor of a Pilsener. They differ slightly in flavor; corn has a sweet “roundness,” while rice is dryer and more neutral in character.

Small-batch brewers may find that the easiest way to incorporate rice or corn is in the form of flakes that have been pregelatinized and are ready to add to the mash kettle. Because these flakes are not manufactured in America and must be imported from Great Britain they are quite expensive and may be cost-prohibitive in small-scale commercial brewing. Instead, microbrewers may want to consider using uncooked adjuncts such as grits, even though this method requires using an additional brew kettle and a more complicated mash. The traditional form of corn as an uncooked adjunct is ordinary corn meal, which is very cheap and readily available. Both yellow and white corn meal are suitable. Rice used as an uncooked adjunct must be ordinary white (debranned) rice, not precooked or “converted.” Short-grain rice is preferred; long-grain rice can be used, but it must be milled before cooking. Rice is more problematic than corn because it does not gelatinize at temperatures below 185 degrees F (85 degrees C).

Untraditional adjuncts include unmalted barley, which is equivalent to chit malt used in some North German Pilseners. It enhances foam retention, imparts a smooth finish and need not result in chill-haze. Unmalted barley flakes imported from Great Britain are considerably cheaper than rice or maize flakes and may be worth considering for microbrewers. Whole barley also can be used, but it must be milled and cooked before it is added into the main mash.

Brewers can use any of these adjuncts in quantities up to 20 percent to produce a light, refreshing Pilsener. Higher amounts, however, dilute the flavor too much and diminish the “Old World” character of the beer.

Sugars are another non-malt source of extract, but they are not employed in traditional lager brewing. In my opinion, they have no place in a European Pilsener. The only exception is the small amount of glucose (corn sugar) used in the bottle carbonation of homebrew.

- Malt Extracts and Grain Syrups -

Pilsener is one of the most difficult styles of beer to brew from malt extract. All malt extracts have been caramelized to some degree during manufacture, so it is very difficult to achieve the light color and clean flavor required of a Pilsener beer. The problem is so acute that many extract manufacturers incorporate corn syrups into their “light” or “lager” extracts and beer kits. This lightens the color but only at the cost of malt character, body, and head retention. Fortunately, there are a few exceptions to the rule.

Malt extracts’ chief advantages are considerable savings in time, and convenience in brewing. These may appeal to homebrewers and also small-scale brewers who operate in a location where it is inconvenient or impractical to remove large amounts of spent grains (the only significant solid waste product of brewing) or where it is more profitable to allocate square footage to customer seating rather than to the extra brewing vessels and allied equipment required for mashing and lautering.

One drawback of malt extract is that it is much more expensive than grain malt. This is inevitable since, in effect, the brewer is paying the manufacturer to do a large part of the processing. Another disadvantage is that malt extract severely limits recipe formulation. I would strongly urge any potential microbrewer who plans to make Pilsener beers a mainstay of his business to perform some careful trial brews. Beer quality must be the paramount consideration, and you must satisfy yourself that your extract-based Pilsener will meet the standard set by the finest imported and domestic brands.

Grain syrups are a natural accompaniment to malt extract since they are essentially “liquid adjuncts.” They also are well worth considering for the grain brewer who wishes to make an occasional batch of light-bodied Pilsener but who cannot justify the complication and expense of a cereal cooker. Corn and rice syrups both are available, as is barley syrup, though it might be slightly harder to locate. As a result of processing, the subtle differences imparted by the choice of grain often are difficult to detect. Of far more importance is the manufacturing process, which must create a product with at least 40 to 50 percent maltose and a substantial content of dextrins and maltotriose. Some grain syrups are almost entirely glucose and produce a thin, dry beer with a cidery flavor.

Zatec (Saaz) hop fields in Czechoslovakia, illuminated by a pale winter sun.

- Hops -

Traditional Pilsener beer features a strong, fine hop aroma that can only be obtained from the traditional low-alpha or “noble” variety of hops such as Hallertauer, Tettnanger, or Saaz. High-alpha varieties can be used for bittering, but they have a high cohumulone content that imparts a coarse, clinging bitterness. Such hops also often contain sharp-smelling hydrocarbons like pinene, which must be driven off by a long, vigorous boil.

One thing the brewer must keep in mind is that the rate of boil-off depends very much on the vigor of the boil and the design of the kettle. Therefore, some brewers may conclude that the choice of hops for the first addition (forty-five to sixty minutes before the end of the boil) makes no difference to the aroma and flavor of the finished beer. Others may find that they must use noble hops exclusively in order to get the best results. If trial brews are not possible, the latter is obviously the safest course.

For the finish or aroma hops (whether added near the end of the boil, or in the hop back or lager tank), noble hops are absolutely necessary, and the Saaz variety is the overwhelming choice of European brewers. You may wish to try other types such as Hallertauer, Styrian Golding, Tettnanger, Spalt, Perle, or Hersbrucker. Saaz is strongly preferred, however. Its aroma is almost a requisite feature of a “true” Continental Pilsener.

The merits of whole hop flowers versus pellets have been argued in the literature for some years now. There seems to be general agreement that the grinding and compressing process destroys a certain amount of the most delicate aromatic components. On the other hand, once pelletized, the hops are much more stable than the whole flowers and also possess enormous practical advantages. In practice, most microbrewers probably will choose between whole and pellet hops based on their brewing process. One fact of importance to Pilsener brewers is that Saaz hops are much more readily available in pellet form.

Because hop character is so crucial to a Pilsener, the brewer must exercise the greatest care in selecting and storing hops. One difficulty posed by pellets is that one cannot rub them in order to release their aroma and thus evaluate their freshness before buying them. Whatever the form, hops must be stored properly to prevent oxidation. Experiments have shown conclusively that oxidation is the only significant factor in hop deterioration. If hops can be stored in an atmosphere devoid of oxygen, temperature is irrelevant. When hops are stored in normal air, however, temperature and variety determine the rate of oxidation. Most noble hops store very poorly and can lose a substantial proportion of their alpha acid and aromatics in a few weeks if kept at room temperature. They should be kept in a freezer at 0 degrees F (-18 degrees C) if they cannot be packaged in nitrogen or carbon dioxide.

Let me remind you to select hops with a reliable analysis of alpha acid content. Few small brewers have the resources or time to analyze their own hops. The best course is to anticipate your hop requirements and have sufficient freezer storage to purchase all the hops you will need during the autumn; when the new crop becomes available. Selection is best at this time.

- Yeast -

Traditional Pilsener beer is fermented and lagered at low temperatures, which is an important consideration in selecting a yeast strain. Bear in mind that the yeast must be suitable to the process employed. For example, in recent decades, there has been a strong trend toward warmer fermentations that reduce energy costs and processing time. Yeast strains suited for this American-style fermentation may go dormant at colder temperatures.

Another factor of importance to small brewers is the stability of the yeast strain. A yeast prone to mutation may be acceptable to a large commercial brewery that can afford to watch it closely and reculture frequently, but such measures may not be possible for a microbrewer, and are certainly out of the question for most homebrewers. Stability is vital if consistent quality is to be maintained.

Flocculation is another property that must be carefully considered. An ideal yeast stays in suspension and ferments the wort down to the limit, then settles out quickly and firmly once fermentation is over. This is especially important for homebrewers who use bottle fermentation to carbonate their beer because they cannot filter out the yeast. However, these two traits are to some extent mutually exclusive. One factor that can complicate flocculation in the homebrew process is cold tolerance. Some strains of yeast shut down completely and flocculate if the wort temperature drops below a critical point. They then have to be roused back into the wort in order to restart fermentation. Such yeasts virtually require a system of temperature control in order to function satisfactorily.

Attenuation is another key factor. All strains of true lager yeast, unless they are mutants, ferment maltotriose and many minor wort sugars such as melibiose. However, the strength of their enzyme systems varies considerably, and some strains take a long time to finish the fermentation of these complex sugars. This trait is not a disadvantage for traditional lager beers that are carbonated and matured during a long, cold secondary fermentation in the lager tank. However, the modern trend is to finish the fermentation quickly, and for this purpose it is preferable to have a yeast that can finish off the minor sugars in a brief time span.

Finally, the flavor characteristics of the yeast must be considered. Lager beers, including Pilseners, have a clean palate in which the basic ingredients of malt and hops should predominate. Therefore, an obviously estery aroma, such as is typical of most ales, is undesirable, and low fermentation temperatures, as well as yeast strain selection, are necessary to avoid this. Nonetheless, it remains a fact that absolute neutrality is neither possible nor desirable. All yeasts produce a host of by-products in addition to ethanol and carbon dioxide, and therefore the choice of yeast exerts a great effect on the flavor of the finished beer.

Some lager breweries use yeasts that have a slight estery character. But generally the esters are in the secondary rather than the primary flavor component range and impart a very subtle fruity note to the aroma. For example, Anheuser-Busch highly prizes its yeast for its delicate apple character.

As mentioned earlier, Pilsner Urquell exhibits a noticeable, but subtle characteristic of diacetyl. However, the level of diacetyl, one byproduct of yeast, must be highly controlled in a lager beer. As with esters, yeasts vary considerably in regard to this compound. Often brewers must adjust their fermentation system in order to maximize diacetyl reduction with a yeast that is weak in this respect. Optimally, a brewer can select a strong diacetyl reducer as the production yeast.

Fusel alcohols and fatty acids also have strong unpleasant flavors that are undesirable in Pilseners. Fortunately, the low fermentation temperatures used in lager brewing make these by-products less of a problem than they are in ale brewing. Most commercial strains are satisfactory if handled sensibly.

Of paramount importance to Continental Pilseners is the influence of the yeast strain on the primary flavor components, the malt and hops. Many Continental lager yeasts accentuate the sulfury compounds (DMS, for example) that contribute so much to the malt aroma of a beer. (Actually, this is probably a matter of not removing these compounds during fermentation, rather than actively creating them.) Some yeasts also emphasize the hop flavor and aroma, probably because they produce larger amounts of acetic and other organic acids. It should be noted that fermentation temperature also has a great influence on these flavor components; nonetheless, it is a well-known fact among brewers that some strains of yeast emphasize the hops, while others emphasize the malt, still others emphasize both, and some emphasize neither. Obviously a Continental Pilsener needs a yeast that accentuates the hops. Full-bodied, malty Pilseners benefit from a sulfury note in the yeast as well, but this is not important if you are trying to make a lighter version of the style.

While I hesitate to recommend specific strains, I want to state here that my experience has convinced me that the choice of yeast is absolutely critical if one wishes to achieve true European flavor in a Pilsener-style beer. Typical American yeast strains simply do not produce the hop and malt flavors characteristic in the Continental brews. I have demonstrated this with duplicate test batches in which the only variable was the pitching yeast. The beer fermented with the yeast of European origin had a stronger malt flavor and tasted as if it had been brewed to a higher hop rate than its counterpart.

All the European lager yeasts I have used were obtained from Wyeast Labs. Other laboratories supplying yeast to microbrewers and homebrewers carry similar strains. The two I have experience with are Wyeast 2042 (Danish) and Wyeast 2206 (Bavarian). The 2042 emphasizes hops and is quite suitable for a light-bodied Pilsener. It is a slow flocculator at normal temperatures of 46 to 52 degrees F (7 to 11 degrees C) but needs temperature control because it flocculates and ceases fermentation if the temperature falls below 40 degrees F (4 degrees C). The 2206 emphasizes malt as well as hops and is quite suitable for full-bodied Pilseners and Bavarian lagers. It is temperature tolerant and settles out well once fermentation has been completed. Both yeasts are good diacetyl reducers and produce only low levels of other by-products.

My recommendation of these yeast strains does not imply that others are inferior. Furthermore, the performance of any yeast depends on its being properly handled and maintained. However, I want to state here for the record that I have never found a dried lager yeast—domestic or imported—that gave professional quality results.

- Water -

One of the grand generalizations of brewing is that soft water is necessary for making lagers, especially pale lagers. This statement is more or less true, but there are plenty of exceptions. Dortmund, one of the great brewing centers of Germany, has a water supply with around 1,000 ppm of total dissolved solids, which would put its water in the “extremely hard” classification. Yet both Pilseners and the famous Dortmund Export style are successfully brewed there. The fact is that the whole concept of water hardness is so vague that it is nearly useless for purposes of evaluating brewing water. What matters is the specific ion content of the water, and the fact is that by adjusting the brewing process, Pilseners can be brewed from vastly different water supplies.

Nonetheless, it is worthwhile to comment on a few specifics to point out some potential difficulties and the corrections that a brewer may need to make. Consider first the calcium content. Most brewing chemists believe that this ideally should be in the range of 50 to 100 ppm. The main effect of calcium is to assist in lowering the mash pH into the desirable range of 5.5 to 5.2. There are other ways of doing this, however. In Plzeň, the water contains only about 10 ppm calcium, but the decoction mash effectively lowers the pH into the proper range. It is easy to raise the calcium content of water by adding calcium chloride or calcium sulfate and I would recommend this procedure especially if one is using an infusion mash. But the problem has to be approached empirically. The overriding concern is the mash pH, and the calcium content must be adjusted accordingly.

Magnesium is well known for its dry, bitter flavor, which is especially unpleasant in Pilseners. It is a necessary yeast nutrient, but malt contains plenty of magnesium for this purpose, and the ion should never be added to brewing water.

Likewise, trace amounts of certain other metallic ions such as manganese, copper, and zinc are necessary for yeast nutrition. Most natural water supplies contain plenty of these, but occasionally brewers find it necessary to add small amounts of zinc sulfate to their wort. Inclusion of some copper equipment in the brewing plant will take care of the copper requirement. I must emphasize that we are speaking about very small amounts of these ions. In general, metallic ions (except calcium) are not wanted in brewing water, and substantial amounts of iron or manganese (which are common in ground water) mean that lime or other treatment will be needed to remove them. Nickel, zinc, and other ions also impart a metallic taste and/or contribute to haze problems.

Sulfate is well-known for imparting a sharp, dry edge to hop bitterness, and this characteristic does not complement the flavor of Pilsener beers. In general, the higher the sulfate content of your water supply, the lower your hop rate must be. Levels under 100 ppm usually are acceptable. The effect of sulfate is magnified and worsened by potassium and sodium. Unfortunately, the sodium content of many fresh water supplies has increased in recent decades, partly because detergent manufacturers have replaced phosphates with sodium compounds in their formulations.

Chloride emphasizes sweetness, and in quantities under 150 ppm, it has no adverse effects. For this reason, calcium chloride often is preferable to calcium sulfate for adjusting the mash pH.

Without a doubt the most important ion in brewing water is bicarbonate/carbonate. The content of this ion is often called the “total alkalinity” of the water supply. The one firm rule a brewer cannot escape is that pale lagers, including Pilseners, should be brewed from water with low-level total alkalinity—ideally under 50 ppm and certainly not higher than 75 ppm. Levels higher than this cannot effectively be countered during the mash. Fortunately, it is fairly simple to remove excess bicarbonate from most water supplies, either by lime treatment, acidification, or boiling.

Treatment of water for Pilsener brewing should be tailored to the water supply in question. The following treatments should be considered. However, very few water supplies will need all of them.

First is chlorine removal, which is recommended for all water supplies that have been chlorinated. In practical terms, homebrewers can remove all free chlorine by boiling the water. Microbrewers find it more economical to install a carbon filter. Chlorination off-flavors are especially noticeable in Pilsener beers.

Next is the reduction of the total alkalinity (carbonate/bicarbonate ion content). Many municipalities do this when they “soften” the water through lime treatment. Lime is the most economical means of reducing total alkalinity, but the treatment requires a large mixing tank. Lime is also very effective in removing iron. However, most small-scale brewers prefer to boil the water and decant it off the chalk precipitate, or to use acid. The acid should be chosen carefully to be sure that it will not add undesirable flavors. Hydrochloric, lactic, and phosphoric acids (USP or food grade only) are generally suitable.

Other undesirable ions affect the characteristics of Pilsener and must be removed from the brewing water. For example, if you are determined to make a highly hopped Pilsener, you should consider the sulfate and sodium levels of your water supply. These ions can be reduced by running part of your brewing water through a deionizing filter or a reverse-osmosis filter. These demineralizers remove virtually all solids and produce the equivalent of distilled water. I do not recommend complete deionization of the brewing water because it removes the trace elements needed by yeast. It is better to blend demineralized brewing water in order to reduce harmful ions to acceptable levels.

Finally, you may need to restore the calcium content because many of these treatments remove calcium along with other ions. As noted above, calcium chloride or calcium sulfate can be used for this.

Carbon filters and demineralizing filters can be purchased from laboratory and food-industry equipment suppliers. Chemicals for water treatment are available from various chemical supply houses. For details on the various treatment procedures, the reader should consult the brewing manuals listed in the Bibliography.

- Other Ingredients -

Besides malt, adjuncts, hops, yeast, and water, the only materials generally used in brewing Continental Pilseners are clarification aids such as silica gel, Irish moss (copper finings), and polyvinylpyrollidone (known as PVP or Polyclar™). These materials are readily available through brewing supply houses.

EQUIPMENT

The equipment needed for brewing Pilsener is no different from that required for brewing other lager beers. Several items are optional, depending on the brewer’s choice of method and other variables.

- Mills -

A microbrewer may choose to omit a malt mill and buy malt in a precrushed form. This lowers the initial cost of the brewery and may lower insurance costs since the dust generated by grain mills can be explosive. Homebrewers, too, may opt for precrushed malt. Available hand mills do not give as good a crush as a roller mill, so if homebrewers can get their malt precrushed in such a mill, they may find the extra cost well worthwhile.

The chief drawback of not owning a mill is the higher price of precrushed grain. There is also the problem of storage; crushed malt is much more vulnerable to moisture pickup than is whole grain. To keep precrushed malt in peak quality, the packaging must be of a high standard. Another disadvantage of using precrushed malt is that it is only available from a few domestic malting companies. If you want to use imported malt you must be able to crush it yourself.

Assuming the brewer chooses to mill his own malt, the next choice involves the design. Practical experience indicates that a simple mill with a single pair of rollers (minimum diameter eight to ten inches) is adequate for well-modified lager malt. However, undermodified malt such as that used at Plzeň requires a four-roll mill for a good crush.

- Brewing Kettles -

A brewer may wish to employ the decoction system or the so-called “mixed-mash” method in which some or all temperature boosts are accomplished by boiling a fraction of the mash and returning it to the main kettle. In this case, he will need two mash kettles: a main mash kettle with a capacity at least equal to the batch size, and a second kettle with a capacity of about two-thirds of the main kettle. Note that the mixed-mash method, which must be used in recipes calling for raw cereal adjuncts, requires that both kettles be heated.

If a brewer uses the classic triple-decoction mash system, in which temperature boosts are accomplished by removing a portion of the mash three different times and boiling it, it is theoretically possible to provide heating only for the smaller vessel. This can lower the initial cost of the equipment somewhat. But I recommend that both mash kettles in a decoction system be heatable simply because there are bound to be times when additional BTUs are needed to achieve a particular rest temperature.

Step-infusion mashing, in which temperature boosts are accomplished by heating the mash kettle, requires only a single vessel. This is therefore the cheapest method, both in the initial investment and ongoing energy costs. An unheated mash kettle must be very well-insulated to avoid heat losses during the prolonged rests.

Another decision faced by the brewer is whether to combine the mash and lauter tuns. This is the traditional British arrangement, and the simplicity and economy are very attractive. It makes particular sense for small microbreweries where only one brew per day is made. Separate vessels are worthwhile when two or more brews are made in succession.

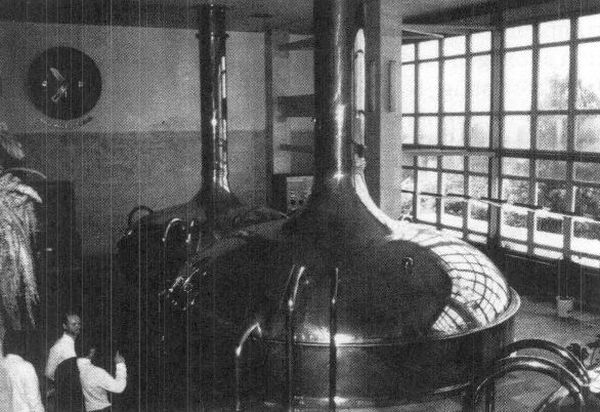

Mash tun and lauter tun at the Budweiser Budvar brewery.

Most other brewing equipment depends on the brewer’s specific choices. For example, if one uses whole hops, one must have a hop back or strainer to separate them from the wort.

Several pieces of equipment are particularly important in the brewing of Pilsener beer. One is a whirlpool or some other means of separating the trub from the boiled wort. Another is a wort cooler, which gives a rapid drop to pitching temperature. The clean taste of this beer style depends upon a good cold break and trub removal. Also, some method of controlling temperature during fermentation and lagering is very important both to the clarity and flavor of the finished beer. For homebrewers, having a refrigerator or two is very useful; for microbrewers, fermenters with cooling jackets are virtually required.

The design of the wort cooler is of some importance. Because Pilseners show oxidation very readily, it is best to avoid aerating the hot wort. Oxidation of certain wort compounds (called reductones) may permit them to function as oxygen carriers during beer storage, so they actually facilitate staling. For this reason, even more than for sanitation, I recommend closed heat-exchange coolers for microbreweries. For homebrewers, the counterflow design is good provided that sanitation is strict. If you choose an immersion cooler, use it right in the boiler (with the lid on) rather than transferring the wort to a separate container for chilling.

The last point to be made about equipment has to do with the transfer of mashes, wort, and beer from one container to another. Pilsener has a very full, fresh hop aroma, so it is even more vulnerable to air pick-up than other lager beers. Disappearance of hop aroma is the first sign of oxidation, which is followed by the presence of a cheesy character reminiscent of old hops. To avoid these effects the mash and hot wort, as well as the fermenting and finished beer, must be handled gently. Any pump (including the positive-displacement rotary as well as the cheaper impeller types) causes a certain amount of turbulence and aeration. There is, therefore, good reason to favor the traditional tower design for the brewhouse because it allows most transfers of wort to be done by gravity. More importantly, the finished beer should be pushed by carbon dioxide pressure through the filters (if used) into the bright beer tanks. This transfer method actually removes dissolved oxygen from the beer rather than introducing it.

Almost all commercial Pilsener beer is filtered. I urge all lager brewers not to use tight filtration as a substitute for other means of clarification. It is often necessary to filter the fresh beer to remove a slight yeast haze and obtain a sparkling product, but only a light, “polish” filtering should be needed.