In mid-2007, a major survey found that more than a third of Americans regularly consulted Wikipedia. Since then, that percentage has probably grown, just as Wikipedia has—at the rate of several thousand new articles every day, plus the lengthening of articles via more than 100 edits every minute.

In January 2008, O’Reilly published Wikipedia: The Missing Manual. That book is a how-to manual for folks who want to edit Wikipedia articles and become more active in the Wikipedia community. This pocket guide is mostly about understanding and making the most of Wikipedia as a reader. But it also includes most of the first chapter of Wikipedia: The Missing Manual—Editing Your First Article—for when you’re ready to consider the next step: contributing to the largest collective writing project in the world.

So, why do people contribute to Wikipedia? The question is relevant to you as a reader, because a writer’s motivation offers some clues about the writing’s trustworthiness. The reasons vary from person to person, and usually are a mixture of factors, but here are a couple:

As a way of helping other people understand the world—and perhaps changing the world as a result.

To give back to the community that provides a valuable resource by contributing to it.

Clear, factual writing is challenging, interesting, and often fun. Working jointly with others on improving articles in Wikipedia is intrinsically rewarding.

Wikipedia is a collaboratively written encyclopedia. It’s a wiki, which means that the underlying software (in this case, a system called MediaWiki) tracks every change to every page. That change-tracking system makes it easy to remove (revert) inappropriate edits, and to identify repeat offenders who can be blocked from future editing.

Wikipedia is run by the not-for-profit Wikimedia Foundation; that’s why you don’t see advertising on any of its pages, or on any of Wikipedia’s sister projects that the Foundation runs (more on those later). To date, almost all the money to run Wikipedia and its smaller sister projects has come from donations. Once a year or so, for about a month, you may see a fundraising banner instead of the standard small-print request for donations at the top of each page, but, so far, that’s about as intrusive as the foundation’s fundraising gets.

The Foundation has only about a dozen employees, including a couple of programmers. It buys hardware, designs and implements the core software, and pays for the network bandwidth that makes Wikipedia and its sister projects possible. But it doesn’t have the resources to do any of the writing for those projects. All the writing (known in the community as editing) is done by people who get no money for their efforts, though plenty of personal satisfaction.

Wikipedia is an encyclopedia that anyone can edit. You don’t have to register to edit articles. If you do register, you don’t even have to provide an email address (although you should, in case you forget your password). Because of the variety and number of editors, Wikipedia is immense in scope—2.3 million articles as of April 2008, and over 1 billion words (more than 25 times as many as the next largest English-language encyclopedia, the Encyclopaedia Britannica). By the same token, Wikipedia is—and will continue to be—a work in progress.

The best answer may be “Compared to what?” Wikipedia wouldn’t be one of the world’s top 10 most visited Web sites (that includes all 250-plus language versions, not just the English Wikipedia) if readers didn’t find it better than available alternatives. To be sure, Wikipedia is an encyclopedia under construction. As the general disclaimer (see the Disclaimers link at the bottom of every page) says, “WIKIPEDIA MAKES NO GUARANTEE OF VALIDITY. Please be advised that nothing found here has necessarily been reviewed by people with the expertise required to provide you with complete, accurate or reliable information.”

On the other hand, Wikipedia has been reviewed by a number of outside experts, most famously in an article published in Nature in December 2005. In that article, a group of experts compared 42 articles in Wikipedia to the corresponding articles in Encyclopaedia Britannica. Their conclusion: “The number of errors in a typical Wikipedia science article is not substantially more than in Encyclopaedia Britannica.” (The actual count was 162 errors vs. 123.) That comparison is now more than 2 years old, and editors have continued to improve those 42 articles as well as all the others that were in the encyclopedia back then. (For a full list of outside reviews of Wikipedia, see the Wikipedia page Wikipedia:External peer review.)

None of which is to say that Wikipedia editors are wildly happy about the quality of many, if not most articles. Those most knowledgeable about Wikipedia have repeatedly talked about the need to improve quality, and that quality is now more important than quantity. The challenge is whether Wikipedia can implement a combination of technological and procedural changes that’ll make a difference, because so far relatively incremental changes haven’t made much of a dent in the problem of accuracy.

So, should you trust Wikipedia? That should depend somewhat on the article. If you see a star in the upper right corner (see Figure 1-1), indicating a featured article, you can be virtually certain that what you’ll read is correct, and that the cited sources back up what’s in the article.

Figure 1-1. Featured articles (articles with the highest assessed quality in Wikipedia) have a star in the upper right corner. You can click the star to learn how articles get their featured status.

You’ll find that each article contains clues to its reliability. If you see a well-written article with at least a reasonable number of footnotes, then you should be reasonably confident that almost all the information in the article is correct. If you see a lot of run-on sentences and templates noting a lack of sources, point of view problems, and so on, then you should be skeptical.

You can get more clues from the article talk (discussion) page; just click the “discussion” tab. At the top, see if a Wikipedia WikiProject (a group of editors working on articles of common interest) has rated the article. Also at the top, look for links to archived talk pages, indicating that a lot of editors have talked a lot about the article, and have therefore edited it a lot.

If there are no archive pages, and not much indication of activity on the talk page you’re looking at, then the opposite is true—few editors have been interested in editing the article. That doesn’t mean it’s not good—some excellent editors toil in relative backwaters, producing gems without much discussion with other editors. Still, absence of editor activity should make you more doubtful that you’ve found an example of Wikipedia’s best.

Bottom line: Think of Wikipedia as a starting place. If you’re just interested in a quick overview of a topic, it may be an ending place as well. But Wikipedia’s ideal is for articles to cite the sources from which their content was created, so that really interested readers can use those sources to get more information. If the editors at Wikipedia are doing things right, those sources are the ones that readers can absolutely depend upon to be informative and accurate.

There are two basic ways to find interesting articles in Wikipedia: Do a search, or browse, starting from the Main Page. Wikipedia has lots of organizing features depending on how you want to browse, like overviews, portals, lists, indexes, and categories. But for a bit of amusement, you can also try a couple of unusual ways to go from article to article, as discussed in this section.

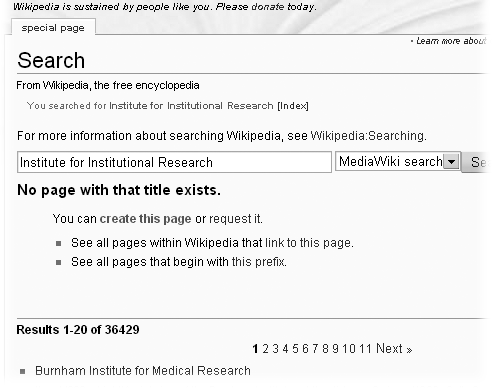

On the left side of each Wikipedia page, you’ll find a box labeled “search”, with two buttons—Go and Search. Wikipedia’s search engine is widely acknowledged to be not particularly good. Your best bet to find what you want is to type the title you’re looking for into the search box, and then click Go (or press Enter). If you’re right, and Wikipedia finds an exact match, you’ll be at that article. If it doesn’t find an exact match, Wikipedia provides you with a link to “create this page”, which you should ignore if you’re searching only for reading purposes. It also provides you some search results. Figure 1-2 shows the result of a failed search for the title Institute of Institutional Research, including the start of some best guess results).

Note

If you click “Search” for curiosity’s sake, you’ll just get some so-so search results. For example, if you search for Reagan wife, the article Nancy Reagan shows up 6th and Jane Wyman shows up 16th. Worse, the context Wikipedia’s result page shows is terrible. With a Google search, by contrast, you can get these two names from the context shown for the first result without even having to click a link.

Figure 1-2. When Wikipedia can’t find an exact match to a Go request, it provides search results, but it also offers a link to create an article with the same name as the word or phrase you entered.

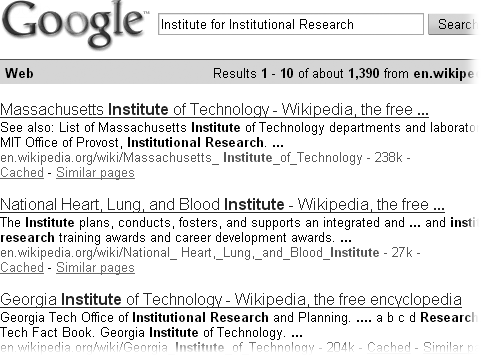

If you don’t arrive at an article page when you click Go, and you don’t find what you’re looking for in the search results toward the bottom of the page, your next best move is to switch to another search engine. Wikipedia makes this very easy for you—just change “MediaWiki search” to another menu choice, as shown in Figure 1-3.

Figure 1-3. Wikipedia makes it easy to pick another search engine. Here Google’s being selected, but other search engines are available. Take advantage of this option if your initial Go attempt doesn’t succeed.

Figure 1-4 shows the search done again using Google. To those familiar with the Wikipedia search engine, it’s not surprising that the top results are completely different.

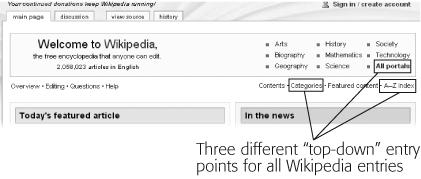

You can also navigate Wikipedia via a number of different starting points. The best way to get to them is via the links near the top of the Main Page, as shown in Figure 1-5. Every Wikipedia page has a link to the Main Page, on the left side, in the navigation box below the Wikipedia globe. From the Main Page, you can see the vastness of Wikipedia via three different approaches: categories, portals, and the A-Z index.

Figure 1-5. Wikipedia’s Main Page is accessible via a single click from any other page in Wikipedia. At the top are three links to starting points within Wikipedia that provide different top-down views.

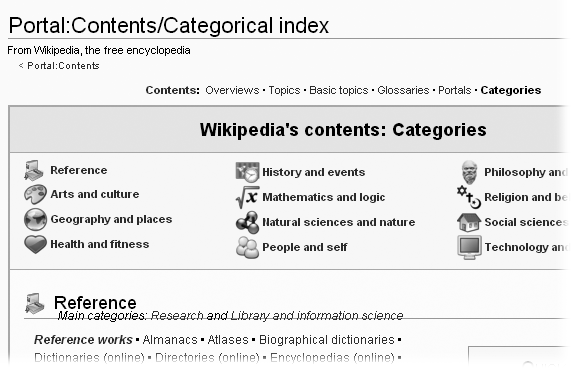

Any article may belong to one or more categories, which you’ll find listed at the bottom of the article. Like everything else in an article, editors add the categories, so categories are only as accurate as the people who enter them; like everything else, if someone sees a mistake, she can fix it. When you click the Categories link shown in Figure 1-5, you’ll see the master index (see Figure 1-6).

Figure 1-6. Here’s the top-level list of categories. It’s the starting point for drilling down to find all articles in any particular subcategory.

The text in Figure 1-6 is hand-crafted, not computer-generated, but once you leave the page via a link on it, the lists you’ll see will be computer-generated and thus completely current. For example, when you click Geography at the top of the index, that takes you to a section of the page called “Geography and places”, with the main category Geography. Click that word, and you’ll see Figure 1-7. If you’re interested in Geography, you can drill down in whatever subcategory you want until you reach actual links to articles, and then follow them.

Figure 1-7. The category Geography had 28 subcategories when this screenshot was taken. In the “B” section, you see an expansion of one of those subcategories, Branches of Geography, displaying all the sub-subcategories until there are no further ones, along one line of that subcategory.

Note

Not every article in Wikipedia is intricately categorized. For example, at the bottom of the Category:Geography page, you see articles in that category which are not in any subcategory (you can’t see them in Figure 1-7). Those may be truly unique articles, or articles just waiting for further categorization work.

From the Main Page, you can also follow the bolded link “All portals” to the main page for portals (Figure 1-8). Like categories, portals can be a great way to narrow down the number of articles you’re particularly interested in reading, or to lead you to articles that you otherwise might never have known existed.

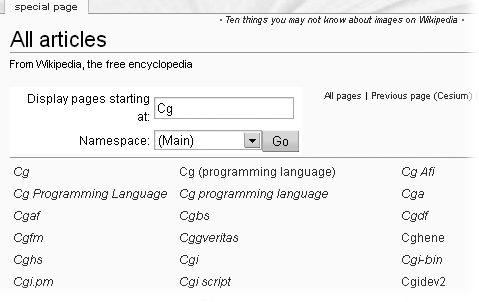

The third entry point link on the Main Page is the A-Z index. It’s equivalent to browsing the shelves of a library, with the books in alphabetical order on the shelves. Figure 1-9 shows what you’ll see if you click the “A-Z index” link at the top of the Main Page.

Figure 1-9. The A-Z index (also called the Quick Index) lets you go directly to a list of articles beginning with any two characters: El or Na or Tr or whatever.

If you were trying, for example, to find the name of an article that began with an unusual pair of letters (say, Cg), then the A-Z index may be helpful (see Figure 1-10).

Figure 1-10. If you pick a two-letter starting pair, in Figure 1-9, and click that link, here’s what you see. The links in regular text are articles; the links in italics (the majority) are redirects, which take you to an article with a different name. Redirects are used for misspellings, for less common variants of a particular name, and for subjects that don’t (yet) have their own articles, and are related to an existing article to which the reader will be directed.

The alphabetical index to articles is actually more useful after you’ve drilled down one level. Now you have the option of searching for articles that start with three or four or even more characters.

You may have noticed, in Figure 1-6 and Figure 1-8, a top-level row of links: Contents, Overviews, Academia, Topics, Basic Topics, and so on. Three of these (Overviews, Topics, Basic Topics) are also high-level entry points into Wikipedia that you might want to check out to see if one or more are interesting.

Figure 1-5 showed you how to start a top-level organization of categories, by clicking the “Categories” link near the top of the Main Page.

When you’re not on the Main Page, every Wikipedia page offers ways of browsing around. Most of them are in the list of links at the left.

If you want to get a sense of the more than two million articles in the English language, a good way is to use the Random article feature. On any page on the http://en.wikipedia.org Web site, you find this link at upper-left (Figure 1-11) that you can click to ask the Wikipedia software to select one of those two million articles for you.

When you’re on an article page, you may find that another link on the left side of the screen, the first in the box labeled toolbox (see Figure 1-12) can also be fun to play with. Click What links here, and you’re now looking at a list of incoming links to the article you were just reading.

Figure 1-12. The toolbox on the left of the screen includes a “What links here” link. Click it to see all the Wikipedia pages that link into the page you’re on.

The list of links may seem random, but it’s not—the oldest page (based on when the page was created) is listed first, the youngest page is listed last (and may very well not show on the screen, which normally lists just 50).

It can also be fun to just follow links from one article to another: For example, start at Kevin Bacon, then go to Circle in the Square Theatre, to Theodore Mann, to Drama Desk Award, to New York Post, and end up at Alexander Hamilton. You can also do the same with the “What links here” links mentioned in the previous section.

Sooner or later, you’re going to want to look something up on Wikipedia when you’re not front of your laptop or desktop computer. Say you’re touring Yellowstone National Park and want to find out about that geyser you’re looking at. If you can get to the Web from your PDA or cell phone, then you can read Wikipedia just like any other Web site—that’s a matter of course. But if your browser does a bad job of displaying Wikipedia articles, you have some options. And if you don’t have mobile Web access, you can still use Wikipedia on the road by downloading what you want to read.

If your PDA or cell phone gives you Web access, it almost certainly has special Web browser software designed to fit large Web pages onto a small screen. But that browser is designed to make best guesses for the billions of pages on the Web, which means it doesn’t understand the structure of Wikipedia pages.

Figure 1-13. The starting page of en.wap.wikipedia.org has a Go button but not a Search option. That makes it challenging to find an article if you’re not sure of the exact name, and less than useful if you’re just browsing.

If you want to read Wikipedia articles from a mobile device, the best thing to do is to go to a special web page as a starting point—a page that does understand how Wikipedia pages are set up—and go from there to the article you want. One such place is http://en.wap.wikipedia.org, an “official” Wikipedia site (see Figure 1-13).

The page Wikipedia:WAP access lists some other starting points from which you can also access mobile-tailored versions of Wikipedia articles. Here are two to consider:

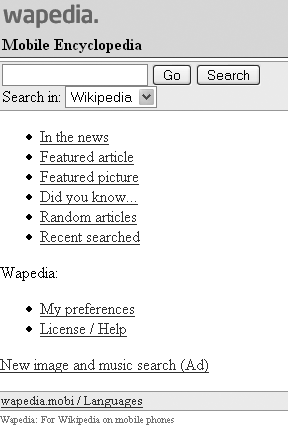

wapedia.mobi, which uses a separate (but current) database of Wikipedia articles. It has its own search engine, and (via the small “languages” link on the starting page) you can also read articles in virtually all other language versions of Wikipedia (see Figure 1-14).

Tip

Wapedia has a tailored version for Blackberries and other PDAs: start at pda.wapedia.mobi/en/.

wikipedia.7val.com (see Figure 1-15) is perfectly suitable for reading Wikipedia, but was particularly designed for editing Wikipedia. (Unfortunately, as of this writing, editing of pages in the English language Wikipedia isn’t possible through this site, due to open proxy issues.)

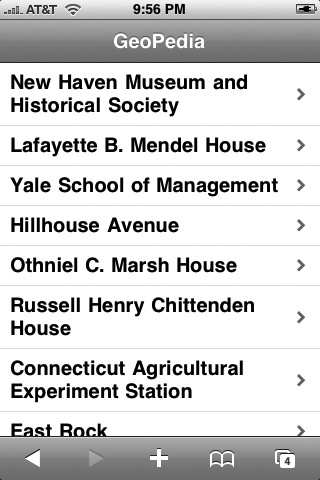

Today’s mobile devices, particularly those like the iPhone, have significantly large amounts of storage, which opens up another possibility for reading offline copies of Wikipedia articles of interest as the mood strikes you. The articles won’t be the most recent versions, but they’ll be accessible—without any charge for network access—whenever you want.

Wikipedia content is free for downloading, and anyone can sell that content and even add advertisements to it. So perhaps it’s surprising that no one’s yet offering Wikipedia articles in an easy-to-download form. Here are two options, both free, both with rough edges:

If you have a Pocket PC or Pocket PC Phone running Windows Mobile 2003 Second Edition or Windows Mobile 5.0, or a Smartphone running Windows Mobile 5.0, you can store sets of Web pages (Web packs) on such a device using the mobile software developer Webaroo (http://www.webaroo.com). To do so, you download a Web pack to your notebook or desktop computer (Windows Vista, Windows XP, or Windows 2000) and then synchronize the download with the mobile device.

It would be nice if Webaroo had a variety of web packs containing only Wikipedia articles—but it doesn’t. There’s just one Wikipedia-only Web pack—Webaroo calls it “The Wikipedia” (see Figure 1-17). Unfortunately, it’s so large that it’s not suitable for a mobile device, and there’s no way to select pages from it (or other Web packs) to create a smaller Web pack. Worst, it’s thoroughly out of date—the article on Barack Obama, for example, was from mid-2005.

If you’re an iPhone or iPod Touch owners, you might consider a very recently announced application called wikipedia-iphone. It includes all articles in Wikipedia as of October 2007. That takes up about 2GB of hard drive space, is a beta version, and the articles will, over time, become less and less current. If those limitations don’t faze you, take a look (from your regular computer) at http://collison.ie/wikipedia-iphone/ for details, including discussions about problems installing it.

Figure 1-17. To download a Webaroo Web pack, you first have to download the Webaroo application. If you have 5 gigabytes or so of available storage on your laptop or desktop computer, you can download the English Wikipedia Web pack. If you have 1GB or more of RAM, you can then actually use that Web pack.

To understand what Wikipedia is, you may find it very helpful to understand what Wikipedia is not. Wikipedia’s goal is not, as some people think, to become the repository of all knowledge. It has always defined itself as an encyclopedia—a reference work with articles on all types of subjects, but not as a final destination, and not as something that encompasses every detail in the world. (The U.S. Library of Congress has roughly 30 million books in its collection, not to mention tens of millions of other items, compared to about two million articles in Wikipedia). Still, there’s much confusion about Wikipedia’s scope.

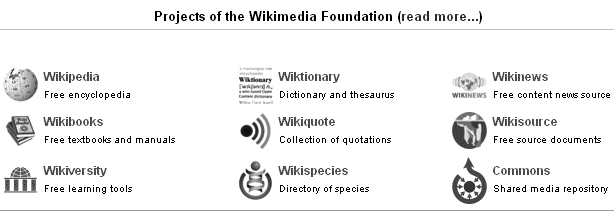

Wikipedia has a well-known policy (to experienced editors, at least) stating what kinds of information belong in the encyclopedia. The sister projects that the Wikimedia Foundation supports, such as Wiktionary, fulfill some of the roles that Wikipedia does not.

The Wikimedia Foundation has seven projects that are parallel to Wikipedia, plus a project called the Commons, where pictures and other freely-usable media are stored for use by all projects in all languages (Figure 1-18).

Figure 1-18. The Wikimedia Foundation has eight parallel projects, the oldest of which is Wikipedia, plus the Commons, a central repository of pictures and other media.

Two of the Foundation’s sister projects overlap (or potentially overlap) with Wikipedia:

Wiktionary is a free, multilingual dictionary with definitions, etymologies, pronunciations, sample quotations, synonyms, antonyms and translations. It’s the “lexical companion” to Wikipedia. It’s common at Wikipedia to move (transwiki) articles to Wiktionary because they’re essentially definitions.

Wikinews and Wikipedia clearly overlap. A story in the national news (Hurricane Katrina, for example) is likely to show up on both. Unlike Wikipedia, Wikinews includes articles that are original writing, but the vast majority are sourced. Because of the overlap between the two, Wikinews has struggled to attract editors. Given a choice, most editors choose to work with Wikipedia articles, which are more widely viewed.

Three of the sister projects have a symbiotic relationship with Wikipedia:

Wikisource is an archive of “free artistic and intellectual works created throughout history.” Except for annotation and translation, these are essentially historical documents (fiction as well as nonfiction) that are in the public domain or whose copyright has expired.

Wikiquote is a repository of quotations from prominent people, books, films, and so on. If you’re reading a page of quotations by a person (like Mark Twain), you can jump to the Wikipedia article via a visible link and vice versa (see Figure 1-19). To date the English version has more than 15,000 pages.

Figure 1-19. It’s easy to jump between Foundation projects when they have different types of materials about the same subject. Shown are three links in the “Mark Twain” article to the Wikimedia Commons (with pictures, as discussed in Wikipedia’s Sister Projects), to Wikisource (all works published by Twain during his life are now in the public domain), and to Wikiquote.

Wikispecies is a directory and central database of taxonomy, aimed at the needs of scientific users rather than general users. Much of its text is language-independent (Latin terms). In fact, it’s the only Foundation project that doesn’t have different versions in different languages. To date there are more than 125,000 articles.

The remaining two projects Wikipedia does not interact with, and these show the scope of the Foundation’s goals:

Wikibooks (previously called Wikimedia Free Textbook Project and Wikimedia-Textbooks), is for creating free content textbooks and manuals.

Wikiversity is a place for the creation of learning activities and development of free learning materials. Its scope is wider than Wikibooks in that it includes things like course outlines and research and learning projects.

Wikipedia’s policy, What Wikipedia is Not, is lengthy, so this section just hits the highlights. Aside from the guidelines that seem obvious to more experienced editors at Wikipedia (“Wikipedia is not a blog, Web space provider, social networking, or memorial site”, “Wikipedia is not a mirror or a repository of links, images, or media files”) and ones that follow from sister projects (“Wikipedia is not a dictionary”, “Wikipedia is not a textbook”), here are several that readers and contributors frequently misunderstand:

Wikipedia is not a publisher of original thought. You won’t find ground-breaking analysis, original reporting, or anything else in Wikipedia that hasn’t been published elsewhere first. (If you do find any of these, it’s a violation of the rules and likely to be removed when other editors discover it.) Thousands of wikis do welcome original research and original writing, but Wikipedia isn’t one of them. (You’ll find hundreds listed at http://WikiIndex.org, a site not associated with Wikipedia.)

Wikipedia is not a directory. Articles aren’t intended to help you navigate a local bureaucracy, find the nearest Italian restaurant, or otherwise include information that other Web pages do a perfectly fine job of maintaining.

Wikipedia is not a manual or guidebook. Wikipedia articles aren’t intended to offer advice, or to include, tutorials, walk-throughs, instruction manuals, game guides, recipes, or travel or other guides.

There actually are wikis for how-to stuff (http://wikiHow.com) and for travel (http://Wikitravel.org), but neither is affiliated with the Wikimedia Foundation and its projects.

Wikipedia is not an indiscriminate collection of information. It’s not the place for frequently asked question (FAQ) lists, collections of lyrics, long lists of statistics, routine news coverage, and “matters lacking encyclopedic substance, such as announcements, sports, gossip, and tabloid journalism.”

If you go to the Wikipedia project’s home page, wikpedia.org (as opposed to the English language Wikipedia site, en.wikipedia.org), you’ll see a globe with a list of ten languages surrounding it—the ten language versions of Wikipedia with the largest number of articles. Scroll down, and you’ll see more than 200 other languages. If you select something other than English, you’ll be reading a completely different Wikipedia.

Note

If you see ??? for one of the ten surrounding languages, that’s Japanese. Your computer’s set of fonts doesn’t know how to display the characters.

It would be great if Wikipedia had a universal translator so an article created in or improved in one language Wikipedia would automatically appear in all the other language Wikipedias, but that’s still a fantasy (at the moment). The reality is that editors of each Wikipedia generally use sources in their own language, which vary widely. Editors also focus their efforts on articles that most interest them and the readers of that language, which vary widely, and they spend relatively little time translating articles from one language Wikipedia to another.

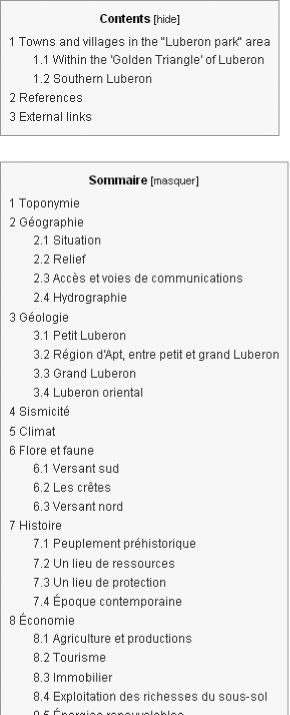

There’s another, more focused way to jump into another Wikipedia, useful if you happen to be able to read two or more languages. When you’re looking at an article, you’ll see, on the left side of the screen, a box labeled “languages”. (You may need to scroll down to see it, and minor articles typically won’t have the box at all.) There you’ll find links to exactly the same topic in other language editions of Wikipedia. For example, Figure Figure 1-20 shows a box with five links for the article “Luberon,” an area of three mountain ranges in France.

Figure 1-20. The English Wikipedia article “Luberon” has links to five articles about that topic that appear in other language Wikipedias: German, French, Italian, Norwegian (nynorsk), and Occitan.

If you read French and wanted more information about Luberon, it’s worth clicking the “Français” link—compare the table of contents in Figure 1-21.

As mentioned earlier, Wikipedia calls itself “the free encyclopedia that anyone can edit”. If you don’t think that you personally have anything to add to it, you’re wrong—Wikipedia is still far from complete. You—as a reader—can help when you see an article with a problem, or if you have suggestions for sources for improving an article, or if you search for an article and don’t find it.

Tip

When you’re thinking about fixing or adding to a Wikipedia article, make sure you have reliable sources at your fingertips first, as described in Missing Information, below.

If you see vandalism in a Wikipedia article, it could easily have just happened, and an editor is in the process of fixing it. Wait 5 minutes or so, and then refresh your browser window (or leave the page and return). If it’s still not gone, you can ask editors to help. Similarly, when you see something in an article that’s incorrect or obviously missing (perhaps you had a question that you expected the article to answer), you can always ask about the problem, which makes it much more likely that active editors will fix it.

Asking about something in (or missing from) an article is an easy six-step process:

At the top of the article, you’ll see a tab called “discussion”. Click it.

The article’s talk (discussion) page opens.

Do a quick scan of the talk (discussion) page to see if your issue or question has already been asked.

If so, you don’t need to post anything; you’re done.

But if you’re looking at something that looks like an error message, which starts, “Wikipedia does not have a talk page with this exact title. Before creating this page, please verify that an article called ... ”, don’t worry—this message means that your question couldn’t possibly have been previously asked, because the talk page didn’t even exist. You can go on to step 3.

Assuming your issue or question is new, click the “+” tab at the top of the talk page to start a new comment.

You’re in edit mode, with two boxes where you can type information.

Type a brief summary of the issue or question into the “Subject/headline” box at the top of the screen (Figure 1-22).

Up to 10 words should be enough.

In the main edit box (see Figure 1-22 again), explain the issue/question. At the end of the last line of your comment, add a couple of spaces and then put four tildes next to each other (like this: ~~~~).

The four tildes tell the Wikipedia software to put a signature and date-stamp there. Figure 1-23 shows an example of a comment after being typed in.

Figure 1-23. Here’s what the input screen shown in the previous figure looks like after someone has entered a section heading (summary) and a comment. It’s now ready to be saved.

Note

The Wikipedia software records, in the page history, exactly the same information that displays when you add four tildes. So you’re not revealing anything by “signing” your comment. If you don’t, an automated editor (a bot) does it for you. You get more credit if you do the signing yourself.

Click the “Save page” button (you may have to tab down or scroll down or page down to see it).

Voila! You’ve posted a comment to Wikipedia, thereby contributing to the improvement of an article (or bringing missed vandalism to the attention of other editors).

Suppose you’re reading an article or a section of a book about something interesting, decide to see if Wikipedia has more information, and find—to your surprise, perhaps—that the relevant Wikipedia article doesn’t have the information that you were just reading, and doesn’t mention the article or book that you have in hand. Clearly the Wikipedia article should cite that source, and should have that information—if it’s interesting to you, it’s interesting to other people. You can help Wikipedia—and future readers—by leaving a note about the source. It’s easy to do.

One quick caveat, first: Wikipedia wants only what it considers reliable sources—sources with a reputation for fact-checking and accuracy. That would include: major city newspapers in the United States, nonfiction books by major publishers, most magazines published nationally, and peer-reviewed articles in academic journals. But it would not include a high school newsletter or the self-published book by your next-door neighbor. This example assumes that what you’re reading meets these criteria.

So, to help Wikipedia, leave a note on the talk/discussion page of the relevant article. Then, just follow the six steps in the previous section, but instead of leaving a question (step 5), leave a comment, saying something like “Here’s a good source for additional information for the article.” Then just type (or, if you’re reading an article or book online, copy and paste) the following five things:

The title of the article or book.

The publisher (in the case of a magazine, just the name of the magazine).

The date the article or book was published (if it’s a book, that might just be the year, or the month and year).

The name of the author(s). (Some newspaper articles don’t list who wrote them; if so, skip this one.)

The URL (Web address) of the book or article, if you’re reading it online and other people can access it without a paid subscription or paying to download it. (If they do have to pay, but you can provide the URL where there is a free abstract or summary or initial paragraphs, that’s a good substitute.)

Finally, as mentioned in step 5 on 5, sign your comment with four tildes, and (step 6) save what you’ve posted. Soon thereafter, hopefully, you’ll see other editors use your information to improve the article.

You’ve searched for an article and didn’t find it, even using an outside search engine (Searching Wikipedia). Now what? Wikipedia has created a page where you can check to see if someone has already suggested that Wikipedia needs such an article. And that page, Wikipedia:Requested articles, has associated pages where you can add the name of the article as a suggestion if no one else already has.

Unfortunately, this page, and its associated pages, isn’t particularly user-friendly for someone unfamiliar with Wikipedia editing. You have to pick the correct general topic area from a list of 10, then a topic area from what can be a long list, and then maybe even go down yet one more level just to see the area of a page where you’re supposed to post.

Finally, when you’re at the right area of the page, you have to figure out how to post your suggestion. If all the sections of all the associated pages were consistently formatted, you’d find instructions here on how to post to them—but they’re not.

An easier way to suggest to the Wikipedia community that an article is needed is to find a relatively close existing article, and then, following the steps on Articles with Problems, post a note on the article’s talk page. When you post, describe the topic that you looked for and couldn’t find, and that you’d appreciate it if a more experienced editor added the subject at the Wikipedia:Requested articles page.