The Solutions in the Compact Have Worked in the Rest of the World

In 2016, Adam Lankford, a political scientist at the University of Alabama, had a simple question: why does the United States have more public mass shootings in its schools, workplaces, churches, mosques, theaters, and public restaurants than other developed countries around the world? To find the answer, Lankford sorted through publicly available data from 171 countries, studying all variables that could possibly explain this phenomenon.

He gathered data on firearm ownership rates, GDP per capita, levels of urbanization, population density, ratio of men to women, and many other factors, then ran a statistical analysis. The stats clearly showed that countries with higher firearm ownership rates have more public mass shooters. The United States is far and away number one in firearm ownership rate and total number of civilian-owned firearms—and massacres. In fact, we are such an outlier among developed nations that Lankford ran an analysis that excluded the United States and just studied the patterns in the other 170 countries. Would the relationship hold? he wondered. The answer was yes. Even when you take the United States out of the equation, firearm ownership is still directly related to the number of mass shootings.

Nineteen years earlier, researchers at the University of California–Berkeley, working with a slightly different data set—violence as opposed to just mass shootings—had concluded something similar. They found that the United States does not have higher crime rates than our global peers; our crime is just far more lethal, resulting in more deaths. “A series of specific comparisons of the death rates from property crime and assault in New York City and London show how enormous differences in death risk can be explained even while general patterns are similar,” the researchers wrote.1 “A preference for crimes of personal force and the willingness and ability to use guns in robbery make similar levels of property crime fifty-four times as deadly in New York City as in London.”

Between 2010 and 2014, Philadelphia had an annual homicide rate of 18.8 per 100,000; Chicago, 16.3; and New York, 5.1. London, by comparison, had a rate of just 1.4 per 100,000 over the same period.2

“I really think the issue is with how easy is it for someone to get a firearm in a given country. So firearm ownership rates are kind of approximating that or estimating it,” Lankford said. Over the last several decades, gun ownership rates may have declined, but access to guns has increased, and more and more firearms are concentrated in the hands of fewer people. It is now easier than ever to obtain a gun in the United States, and a high percentage of mass shooters actually obtain their weapons legally.

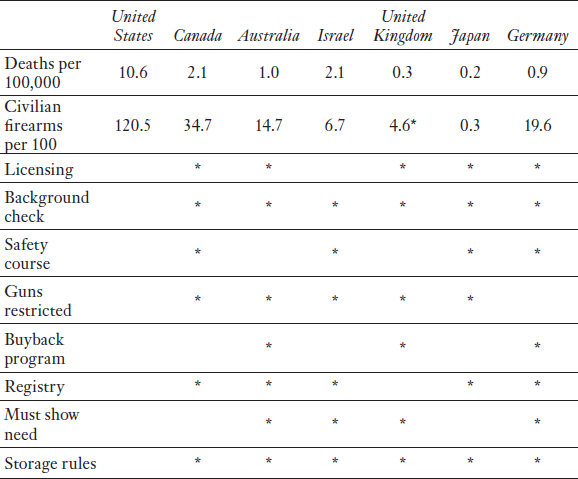

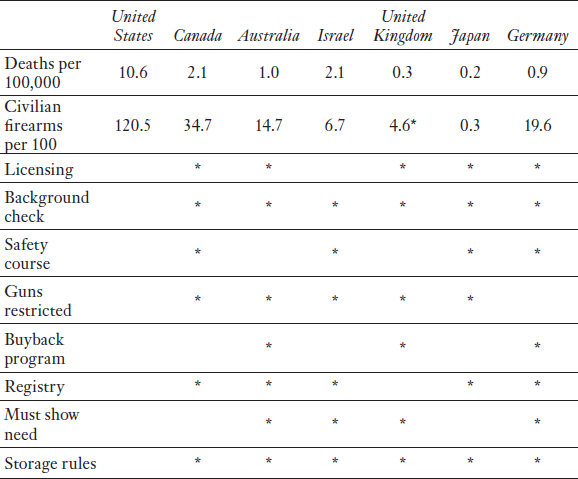

A 2017 survey of gun ownership found that the United States has an estimated 393,300,000 guns in civilian circulation, or 120.5 guns per 100 residents.3 The country with the next largest number of civilian guns is India at a little over 71 million (0.054 guns per 100), followed by China at close to 50 million civilian firearms (0.036 guns per 100). We have about 3,347 times as many guns per capita as China. Americans make up approximately 5 percent of the world population, but we have some 46 percent of the world’s civilian-owned firearms and, not coincidentally, from 1966 to 2012, we were also home to 31 percent of all mass shootings. In 2016, the United States was one of six countries that, collectively, contributed to more than half of all gun deaths worldwide. Together, the United States, Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, and Guatemala represent less than 10 percent of the global population but endure more than half of the entire world’s gun deaths.

Americans are twenty-five times more likely to be murdered by a gun than our peers in twenty-two other high-income countries, eight times more likely to commit suicide, and six times more likely to die of an unintentional shooting.4 Traveling outside of those twenty-two nations to the rest of the world does not paint a prettier picture.

• The United States has a higher rate of gun deaths than any of the twenty-three countries in western Europe.

• The United States has a higher rate of gun deaths than all but one of the twenty-one countries in eastern Europe.

• The United States has a higher rate of gun deaths than all but one of the countries in the Middle East.

• The United States has a higher rate of gun deaths than all but two of the nineteen countries in Southeast Asia, East Asia, and Australia.

• Only seven of forty-three countries in sub-Saharan Africa have higher rates of gun death than the United States.

Almost every other developed country has responded to these truths by restricting access to firearms (usually following an instance of mass shooting) and by adopting the kind of reforms that Australia championed and that I lay out in the Compact: licensing, registration, background checks, firearm restrictions, and safety requirements, just to name a few.

GLOBAL MORTALITY FROM FIREARMS IN SELECTED COUNTRIES

*Number only for England and Wales.

Gun Reforms Around the World

United Kingdom: Following a school shooting in 1996—during which a legally armed gunman killed a teacher and sixteen five- and six-year-old children and injured thirteen more—Parliament banned all handguns within two years. The change came in the midst of increasing crime rates and a growing perception that “American-style” gun culture was taking hold in Britain. As a result, the National Ballistics Intelligence Service reports fewer guns on the streets. In 2012, Great Britain experienced just thirty-two gun homicides.

Brazil: Brazil has the highest number of annual gun deaths. In 2003, the country responded to growing urban violence with a comprehensive measure that banned civilians from carrying weapons, banned certain weapons, raised the legal age for gun ownership, and established a database of gun owners. That and multiple voluntary government-sponsored gun buyback programs have reduced gun deaths and saved more than five thousand lives. According to Brazil’s Ministry of Health, the effort has taken half a million guns off the streets, and gun deaths have fallen by 70 percent in São Paulo and 30 percent in Rio de Janeiro.

Canada: In December 1989, a student armed with a semiautomatic rifle killed fourteen students and injured twelve others at a Montreal engineering school. In response, Canada passed the 1995 Firearms Act, which requires licensing, registration, and names of three personal references. In addition, applicants have to take a safety course and pass a comprehensive background check during a mandatory sixty-day waiting period. Restricted weapons, like assault rifles, are allowed only if one completes an additional safety course and demonstrates need, as for target shooting competitions.

Germany: Following two school shootings in 2003 and 2009, Germany passed severe restrictions on gun ownership. Germany is now the only country in the world where people under the age of twenty-five are required to pass a psychiatric exam before even applying for a gun license and licensees are subject to a yearlong waiting period. Police are permitted to conduct unannounced spot checks to ensure that guns are properly locked and stored. These policies have contributed to a 25 percent reduction in gun crimes from 2010 to 2015.5

Most of the developed world has embraced a public health approach to gun violence, which seeks to limit gun deaths by changing not the behavior of individual shooters, but the environment in which they operate. Rather than dividing gun owners into good guys and bad guys and arguing that all we have to do is keep the bad guys from owning guns, the policies they have implemented—the ones described in the table above—ensure that fewer guns are available and that they’re harder for anyone to get. Comprehensive background checks, licensing, and safety training all work because they make it harder for people to obtain weapons in the first place and significantly reduce the probability that they will use those weapons to kill themselves or each other.

It is the very same approach that successfully reduced injuries and deaths in motor vehicles (that other symbol of masculinity and freedom). For the first half of the twentieth century, “the traffic safety establishment perpetuated the belief that drivers were responsible for accidents.… Drivers were suspect, while the actions of engineers and automakers were unquestioned. [The proposed remedies] dealt with eliminating driver fault.”6 The motor industry was in denial, with slogans like “It’s the nut behind the wheel.” Its leaders argued that all we had to do was educate people to become better drivers. In the second half of the twentieth century, thanks to the persistent factualism of doctors and scientists, we changed our approach. As a country, we stopped blaming drivers for their deaths and instead established speed limits, installed lighting on our roads, greatly improved the safety features in cars, and tightened the standards one must meet to become a driver. David Hemenway, a public health researcher at Harvard, writes in his classic Private Guns, Public Health, “It is, after all, often easier to change the behavior of a few corporate executives at one point in time than that of two hundred million drivers on a daily basis.”

The same logic has to apply to guns. It is far more efficient (and effective!) to pass reforms that regulate the firearm industry, mandating that these deadly weapons are manufactured with mandatory safety features, for instance, and raising the bar for gun ownership, than it is to change the behavior of millions of people once they already have guns in their hands.

The successes of other countries can guide America to reduce its high levels of gun homicides, suicides, and accidental shootings. The timing of those reforms also offers a hint as to what it will take for the United States to reach its own tipping point and implement the reforms that have already saved so many lives elsewhere.

How can we push our lawmakers to dramatically change their approach to guns? If global experience is any indicator, it will take a combination of Americans demanding change, shaming lawmakers who remain beholden to the NRA, and pushing them to place the interests of their constituents ahead of the financial and political needs of powerful special interests. A single brave politician who can publicly break ties with the NRA and advance bold priorities could become a tipping point to a new—and much more sane—approach to gun policy. “What could happen in the United States is what happened here in Australia, which is a reversal in attitude toward people who own firearms and a realization that you need to treat this just as seriously as the road toll,” Alpers, the Australian gun researcher, told me when I asked him how he saw America solving its gun problem. “Thirty thousand people killed by firearms is a hell of a lot of people, and it will take a determination that will have to be raised [like that] around the road toll, the tobacco disease control, and of course HIV.”

In the chapters that follow, I lay out a road map for driving that determination to achieve real change and implement the policies outlined in the Compact.