The heroic figure of Moses confronting the tyrannical pharaoh, the ten plagues, and the massive Israelite Exodus from Egypt have endured over the centuries as the central, unforgettable images of biblical history. Through a divinely guided leader—not a father—who represented the nation to God and God to the nation, the Israelites navigated the almost impossible course from hopeless slave status back to the very borders of their Promised Land. So important is this story of the Israelites’ liberation from bondage that the biblical books of Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy—a full four-fifths of the central scriptures of Israel—are devoted to the momentous events experienced by a single generation in slightly more than forty years. During these years occurred the miracles of the burning bush, the plagues, the parting of the Red Sea, the appearance of manna in the wilderness, and the revelation of God’s Law on Sinai, all of which were the visible manifestations of God’s rule over both nature and humanity. The God of Israel, previously known only by private revelations to the patriarchs, here reveals himself to the nation as a universal deity.

But is it history? Can archaeology help us pinpoint the era when a leader named Moses mobilized his people for the great act of liberation? Can we trace the path of the Exodus and the wandering in the wilderness? Can we even determine if the Exodus—as described in the Bible—ever occurred? Two hundred years of intensive excavation and study of the remains of ancient Egyptian civilization have offered a detailed chronology of the events, personalities, and places of pharaonic times. Even more than descriptions of the patriarchal stories, the Exodus narrative is filled with a wealth of detailed and specific geographical references. Can they provide a reliable historical background to the great epic of the Israelites’ escape from Egypt and their reception of the Law on Sinai?

The Exodus story describes two momentous transitions whose connection is crucial for the subsequent course of Israelite history. On the one hand, the twelve sons of Jacob and their families, living in exile in Egypt, grow into a great nation. On the other, that nation undergoes a process of liberation and commitment to divine law that would have been impossible before. Thus the Bible’s message highlights the potential power of a united, pious nation when it begins to claim its freedom from even the greatest kingdom on earth.

The stage was set for this dramatic spiritual metamorphosis at the end of the book of Genesis, with the sons of Jacob living in security under the protection of their brother Joseph, who had come to power as an influential official in the Egyptian hierarchy. They were prosperous and content in the cities of the eastern Nile delta and had free access back and forth to their Canaanite homeland. After the death of their father, Jacob, they brought his body to the tomb that had been prepared for him—alongside his father Isaac and grandfather Abraham in the cave of Machpelah in Hebron. And over a period of four-hundred thirty years, the descendants of the twelve brothers and their immediate families evolved into a great nation—just as God had promised—and were known to the Egyptian population as Hebrews. “They multiplied and grew exceedingly strong, so that the land was filled with them” (Exodus 1:7). But times changed and eventually a new pharaoh came to power “who knew not Joseph.” Fearing that the Hebrews would betray Egypt to one of its enemies, this new pharaoh enslaved them, forcing them into construction gangs to build the royal cities of Pithom and Raamses. “But the more they were oppressed, the more they multiplied” (Exodus 1:12). The vicious cycle of oppression continued to deepen: the Egyptians made the Hebrews’ life ever more bitter as they were forced into hard service “with mortar and brick and in all kinds of work in the field” (Exodus 1:14).

Fearing a population explosion of these dangerous immigrant workers, the pharaoh ordered that all Hebrew male infants be drowned in the Nile. Yet from this desperate measure came the instrument of the Hebrews’ liberation. A child from the tribe of Levi—set adrift in a basket of bulrushes—was found and adopted by one of the pharaoh’s daughters. He was given the name Moses (from the Hebrew root “to draw out” of the water) and raised in the royal court. Years later, when Moses had grown to adulthood, he saw an Egyptian taskmaster flaying a Hebrew slave and his deepest feelings rose to the surface. He slew the taskmaster and “hid his body in the sand.” Fearing the consequences of his act, Moses fled to the wilderness—to the land of Midian—where he adopted a new life as a desert nomad. And it was in the course of his wandering as a solitary shepherd near Horeb, “the mountain of God,” that he received the revelation that would change the world.

From the brilliant, flickering flames of a bush in the desert, which was burning yet was not consumed, the God of Israel revealed himself to Moses as the deliverer of the people of Israel. He proclaimed that he would free them of their taskmasters and bring them to a life of freedom and security in the Promised Land. God identified himself as the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob—and now also revealed to Moses his mysterious, mystical name, YHWH, “I am who I am.” And he solemnly commissioned Moses, with the assistance of his brother Aaron, to return to Egypt to confront the pharaoh with a demonstration of miracles and to demand freedom for the house of Israel.

But the pharaoh’s heart was hardened and he responded to Moses by intensifying the suffering of the Hebrew slaves. So God instructed Moses to threaten Egypt with a series of terrible plagues if the pharaoh still refused to respond to the divine injunction to “Let my people go” (Exodus 7:16). The pharaoh did not relent and the Nile turned to blood. Frogs, then gnats, then flies swarmed throughout the country. A mysterious disease decimated the Egyptians’ livestock. Boils and sores erupted on their skin and the skin of their surviving animals. Hail pounded down from the heavens, ruining the crops. And yet the pharaoh still refused to relent. Plagues of locusts and darkness then came upon Egypt—and finally a terrible plague of the killing of the firstborn, both human and animal, from all the land of the Nile.

In order to protect the Israelite firstborn, God instructed Moses and Aaron to prepare the congregation of Israel for a special sacrifice of lambs, whose blood should be smeared on the doorpost of every Israelite dwelling so that each would be passed over on the night of the slaying of the Egyptian sons. He also instructed them to prepare provisions of unleavened bread for a hasty exodus. When the pharaoh witnessed the horrible toll of the tenth plague, the killing of the firstborn, including his own, he finally relented, bidding the Israelites to take their flocks and herds and be gone.

Thus the multitude of Israel, numbering “about six hundred thousand men on foot, besides women and children” (Exodus 12:37), set out from the cities of the eastern delta toward the wilderness of Sinai. But “when the Pharaoh let the people go, God did not lead them by the way of the land of the Philistines, although that was near; for God said, ‘Lest the people repent when they see war, and return to Egypt.’ But God led the people round by the way of the wilderness toward the Red Sea” (Exodus 13:17–18). And when the pharaoh, regretting his decision, sent a force of “six hundred picked chariots and all the other chariots of Egypt” after the fleeing Israelites, the Red Sea parted to allow the Israelites to cross over to Sinai on dry land. And as soon as they had made the crossing, the towering waters engulfed the pursuing Egyptians in an unforgettable miracle that was commemorated in the biblical Song of the Sea (Exodus 15:1–18).

Guided by Moses, the Israelite multitude passed through the wilderness, following a carefully recorded itinerary of places at which they thirsted, hungered, and murmured their dissatisfaction, but were calmed and fed through Moses’ intercession with God. Finally reaching the mountain of God where Moses had received his first great revelation, the people of Israel gathered as Moses climbed to the summit to receive the Law under which the newly liberated Israelites should forever live. Though the gathering at Sinai was marred by the Israelites’ worship of a golden calf while Moses was on the mountain (and in anger Moses smashed the first set of stone tablets), God conveyed to the people through Moses the ten commandments and then the complex legislation of worship, purity, and dietary laws. The sacred Ark of the Covenant, containing the tablets of God’s Law, would henceforth be the battle standard and most sacred national symbol, accompanying the Israelites in all of their wanderings.

Setting off from their camp at the wilderness of Paran, the Israelites sent spies to collect intelligence on the people of Canaan (Numbers 13). But those spies returned with reports so frightening about the strength of the Canaanites and the towering fortifications of their cities that the multitude of Israelites lost heart and rebelled against Moses, begging to return to Egypt, where at least their physical safety could be ensured. Seeing this, God determined that the generation that had known slavery in Egypt would not live to inherit the Promised Land, and the Israelites must remain wanderers in the wilderness for another forty years. Therefore, they did not enter Canaan directly, but by a winding route through Kadeshbarnea and into the Arabah, across the lands of Edom and Moab to the east of the Dead Sea.

The final act of the Exodus story took place on the plains of Moab in Transjordan, in sight of the Promised Land. The now elderly Moses revealed to the Israelites the full terms of the laws they would be required to obey if they were truly to inherit Canaan. This second code of law is contained in the book of Deuteronomy (named from the Greek word deuteronomion, “second law”). It detailed the mortal dangers of idolatry, set the calendar of festivals, listed a wide range of social legislation, and mandated that once the land was conquered the God of Israel could be worshiped in a single sanctuary, “the place that the LORD your God will choose.” (Deuteronomy 26:2). Then, after the appointment of Joshua, son of Nun, to lead the Israelites on their campaign of swift conquest, the 120-year-old Moses ascended to the summit of Mount Nebo and died. The transition from family to nation was complete. Now the nation faced the awesome challenge of fulfilling its God-given destiny.

One thing is certain. The basic situation described in the Exodus saga—the phenomenon of immigrants coming down to Egypt from Canaan and settling in the eastern border regions of the delta—is abundantly verified in the archaeological finds and historical texts. From earliest recorded times throughout antiquity, Egypt beckoned as a place of shelter and security for the people of Canaan at times when drought, famine, or warfare made life unbearable or even difficult. This historical relationship is based on the basic environmental and climatic contrasts between Egypt and Canaan, the two neighboring lands separated by the Sinai desert. Canaan, possessing a typical Mediterranean climate, is dry in the summer and gets its rain only in the winter, and the amount of rainfall in any given year can vary widely. Because agriculture in Canaan was so dependent on the climate, years with plentiful rainfall brought prosperity, but years of low precipitation usually resulted in drought and famine. Thus the lives of the people of Canaan were profoundly affected by fluctuations between years of good, average, and poor rainfall, which directly translated into years of prosperity, hardship, or outright famine. And in times of severe famine there was only one solution: to go down to Egypt. Egypt did not depend on rainfall but received its water from the Nile.

There were good years and bad years in Egypt too—determined by the fluctuating level of the Nile in the flood season, due to the very different rainfall patterns at its sources in central Africa and the Ethiopian highlands—but there was rarely outright famine. The Nile, even if low, was still a dependable source of water for irrigation, and in any case Egypt was a well-organized state and thus prepared for better or worse years by the storage of grain in government warehouses. The Nile delta, in particular, presented a far more inviting landscape in antiquity than is evident today. Today, because of silting and geological change, the Nile splits into only two main branches just north of Cairo. But a wide variety of ancient sources, including two maps from the Roman-Byzantine period, report that the Nile once split into as many as seven branches and created a vastly larger area of well-watered land. The easternmost branch extended into what is now the marshy, salty, arid zone of northwestern Sinai. And man-made canals flowing from it carried freshwater to the entire area, making what are now the arid, salty swamps of the Suez Canal area into green, fertile, densely inhabited land. Both the eastern branch of the Nile and the man-made canals have been identified in recent years in geological and topographical studies in the delta and the desert to its east.

There is good reason to believe that in times of famine in Canaan—just as the biblical narrative describes—pastoralists and farmers alike would go to Egypt to settle in the eastern delta and enjoy its dependable fertility. Yet archaeology has provided a far more nuanced picture of the large communities of Semites who came in the Bronze Age from southern Canaan to settle in the delta for a wide variety of reasons and achieved different levels of success. Some of them were conscripted as landless laborers in the construction of public works. In other periods they may have come simply because Egypt offered them the prospect of trade and better economic opportunities. The famous Beni Hasan tomb painting from Middle Egypt, dated to the nineteenth century BCE, portrays a group from Transjordan coming down to Egypt with animals and goods—presumably as traders, not as conscripted laborers. Other Canaanites in the delta may have been brought there by the armies of the pharaohs as prisoners of war, taken in punitive campaigns against the rebellious city-states of Canaan. We know that some were assigned as slaves to cultivate lands of temple estates. Some found their way up the social ladder and eventually became government officials, soldiers, and even priests.

These demographic patterns along the eastern delta—of Asiatic people immigrating to Egypt to be conscripted to forced work in the delta—are not restricted to the Bronze Age. Rather, they reflect the age-old rhythms in the region, including later centuries in the Iron Age, closer to the time when the Exodus narrative was put in writing.

The tale of Joseph’s rise to prominence in Egypt, as narrated in the book of Genesis, is the most famous of the stories of Canaanite immigrants rising to power in Egypt, but there are other sources that offer essentially the same picture—from the Egyptian point of view. The most important of them was written by the Egyptian historian Manetho in the third century BCE; he recorded an extraordinary immigrant success story, though from his patriotic Egyptian perspective it amounted to a national tragedy. Basing his accounts on unnamed “sacred books” and “popular tales and legends,” Manetho described a massive, brutal invasion of Egypt by foreigners from the east, whom he called Hyksos, an enigmatic Greek form of an Egyptian word that he translated as “shepherd kings” but that actually means “rulers of foreign lands.” Manetho reported that the Hyksos established themselves in the delta at a city named Avaris. And they founded a dynasty there that ruled Egypt with great cruelty for more than five hundred years.

In the early years of modern research, scholars identified the Hyksos with the kings of the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt, who ruled from about 1670 to 1570 BCE. The early scholars accepted Manetho’s report quite literally and sought evidence for a powerful foreign nation or ethnic group that came from afar to invade and conquer Egypt. Subsequent studies showed that inscriptions and seals bearing the names of Hyksos rulers were West Semitic—in other words, Canaanite. Recent archaeological excavations in the eastern Nile delta have confirmed that conclusion and indicate that the Hyksos “invasion” was a gradual process of immigration from Canaan to Egypt, rather than a lightning military campaign.

The most important dig has been undertaken by Manfred Bietak, of the University of Vienna, at Tell ed-Daba, a site in the eastern delta identified as Avaris, the Hyksos capital (Figure 6, p. 58). Excavations there show a gradual increase of Canaanite influence in the styles of pottery, architecture, and tombs from around 1800 BCE. By the time of the Fifteenth Dynasty, some 150 years later, the culture of the site, which eventually became a huge city, was overwhelmingly Canaanite. The Tell ed-Daba finds are evidence for a long and gradual development of Canaanite presence in the delta, and a peaceful takeover of power there. It is a situation that is uncannily similar, at least in its broad outlines, to the stories of the visits of the patriarchs to Egypt and their eventual settlement there. The fact that Manetho, writing almost fifteen hundred years later, describes a brutal invasion rather than a gradual, peaceful immigration should probably be understood on the background of his own times, when memories of the invasions of Egypt by the Assyrians, Babylonians, and Persians in the seventh and sixth centuries BCE were still painfully fresh in the Egyptian consciousness.

But there is an even more telling parallel between the saga of the Hyksos and the biblical story of the Israelites in Egypt, despite their drastic difference in tone. Manetho describes how the Hyksos invasion of Egypt was finally brought to an end by a virtuous Egyptian king who attacked and defeated the Hyksos, “killing many of them and pursuing the remainder to the frontiers of Syria.” In fact, Manetho suggested that after the Hyksos were driven from Egypt, they founded the city of Jerusalem and constructed a temple there. Far more trustworthy is an Egyptian source of the sixteenth century BCE that recounts the exploits of Pharaoh Ahmose, of the Eighteenth Dynasty, who sacked Avaris and chased the remnants of the Hyksos to their main citadel in southern Canaan—Sharuhen, near Gaza—which he stormed after a long siege. And indeed, around the middle of the sixteenth century BCE, Tell ed-Daba was abandoned, marking the sudden end of Canaanite influence there.

So, independent archaeological and historical sources tell of migrations of Semites from Canaan to Egypt, and of Egyptians forcibly expelling them. This basic outline of immigration and violent return to Canaan is parallel to the biblical account of Exodus. Two key questions remain: First, who were these Semitic immigrants? And second, how does the date of their sojourn in Egypt square with biblical chronology?

The expulsion of the Hyksos is generally dated, on the basis of Egyptian records and the archaeological evidence of destroyed cities in Canaan, to around 1570 BCE. As we mentioned in the last chapter in discussing the dating of the age of the patriarchs, 1 Kings 6:1 tells us that the start of the construction of the Temple in the fourth year of Solomon’s reign took place 480 years after the Exodus. According to a correlation of the regnal dates of Israelite kings with outside Egyptian and Assyrian sources, this would roughly place the Exodus in 1440 BCE. That is more than a hundred years after the date of the Egyptian expulsion of the Hyksos, around 1570 BCE. But there is an even more serious complication. The Bible speaks explicitly about the forced labor projects of the children of Israel and mentions, in particular, the construction of the city of Raamses (Exodus 1:11). In the fifteenth century BCE such a name is inconceivable. The first pharaoh named Ramesses came to the throne only in 1320 BCE—more than a century after the traditional biblical date. As a result, many scholars have tended to dismiss the literal value of the biblical dating, suggesting that the figure 480 was little more than a symbolic length of time, representing the life spans of twelve generations, each lasting the traditional forty years. This highly schematized chronology puts the building of the Temple about halfway between the end of the first exile (in Egypt) and the end of the second exile (in Babylon).

However, most scholars saw the specific biblical reference to the name Ramesses as a detail that preserved an authentic historical memory. In other words, they argued that the Exodus must have occurred in the thirteenth century BCE. And there were other specific details of the biblical Exodus story that pointed to the same era. First, Egyptian sources report that the city of Pi-Ramesses (“The House of Ramesses”) was built in the delta in the days of the great Egyptian king Ramesses II, who ruled 1279–1213 BCE, and that Semites were apparently employed in its construction. Second, and perhaps most important, the earliest mention of Israel in an extrabiblical text was found in Egypt in the stele describing the campaign of Pharaoh Merneptah—the son of Ramesses II—in Canaan at the very end of the thirteenth century BCE. The inscription tells of a destructive Egyptian campaign into Canaan, in the course of which a people named Israel were decimated to the extent that the pharaoh boasted that Israel’s “seed is not!” The boast was clearly an empty one, but it did indicate that some group known as Israel was already in Canaan by that time. In fact, dozens of settlements that were linked with the early Israelites appeared in the hill country of Canaan around that time. So if a historical Exodus took place, scholars have argued, it must have occurred in the late thirteenth century BCE.

The Merneptah stele contains the first appearance of the name Israel in any surviving ancient text. This again raises the basic questions: Who were the Semites in Egypt? Can they be regarded as Israelite in any meaningful sense? No mention of the name Israel has been found in any of the inscriptions or documents connected with the Hyksos period. Nor is it mentioned in later Egyptian inscriptions, or in an extensive fourteenth century BCE cuneiform archive found at Tell el-Amarna in Egypt, whose nearly four hundred letters describe in detail the social, political, and demographic conditions in Canaan at that time. As we will argue in a later chapter, the Israelites emerged only gradually as a distinct group in Canaan, beginning at the end of the thirteenth century BCE. There is no recognizable archaeological evidence of Israelite presence in Egypt immediately before that time.

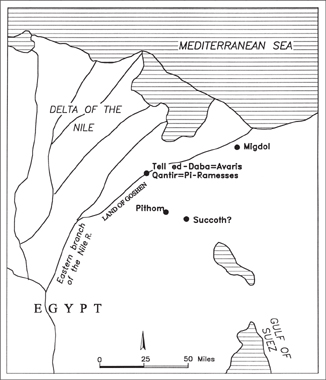

Figure 6: The Nile delta: Main sites mentioned in the Exodus story.

We now know that the solution to the problem of the Exodus is not as simple as lining up dates and kings. The expulsion of the Hyksos from Egypt in 1570 BCE ushered in a period when the Egyptians became extremely wary of incursions into their lands by outsiders. And the negative impact of the memories of the Hyksos symbolizes a state of mind that is also to be seen in the archaeological remains. Only in recent years has it become clear that from the time of the New Kingdom onward, beginning after the expulsion of the Hyksos, the Egyptians tightened their control over the flow of immigrants from Canaan into the delta. They established a system of forts along the delta’s eastern border and manned them with garrison troops and administrators. A late thirteenth century papyrus records how closely the commanders of the forts monitored the movements of foreigners: “We have completed the entry of the tribes of the Edomite Shasu [i.e., bedouin] through the fortress of Merneptah-Content-with-Truth, which is in Tjkw, to the pools of Pr-Itm which [are] in Tjkw for the sustenance of their flocks.”

This report is interesting in another connection: it names two of the most important sites mentioned in the Bible in connection with the Exodus (Figure 6). Succoth (Exodus 12:37; Numbers 33:5) is probably the Hebrew form of the Egyptian Tjkw, a name referring to a place or an area in the eastern delta that appears in the Egyptian texts from the days of the Nineteenth Dynasty, the dynasty of Ramesses II. Pithom (Exodus 1:11) is the Hebrew form of Pr-Itm—“House [i.e., Temple] of the God Atum.” This name appears for the first time in the days of the New Kingdom in Egypt. Indeed, two more place-names that appear in the Exodus narrative seem to fit the reality of the eastern delta in the time of the New Kingdom. The first, which we have already mentioned above, is the city called Raamses—Pi-Ramesses, or “The House of Ramesses,” in Egyptian. This city was built in the thirteenth century as the capital of Ramesses II in the eastern delta, very close to the ruins of Avaris. Hard work in brick making, as described in the biblical account, was a common phenomenon in Egypt, and an Egyptian tomb painting from the fifteenth century BCE portrays this specialized building trade in detail. Finally, the name Migdol, which appears in the Exodus account (Exodus 14:2), is a common name in the New Kingdom for Egyptian forts on the eastern border of the delta and along the international road from Egypt to Canaan in northern Sinai.

The border between Canaan and Egypt was thus closely controlled. If a great mass of fleeing Israelites had passed through the border fortifications of the pharaonic regime, a record should exist. Yet in the abundant Egyptian sources describing the time of the New Kingdom in general and the thirteenth century in particular, there is no reference to the Israelites, not even a single clue. We know of nomadic groups from Edom who entered Egypt from the desert. The Merneptah stele refers to Israel as a group of people already living in Canaan. But we have no clue, not even a single word, about early Israelites in Egypt: neither in monumental inscriptions on walls of temples, nor in tomb inscriptions, nor in papyri. Israel is absent—as a possible foe of Egypt, as a friend, or as an enslaved nation. And there are simply no finds in Egypt that can be directly associated with the notion of a distinct foreign ethnic group (as opposed to a concentration of migrant workers from many places) living in a distinct area of the eastern delta, as implied by the biblical account of the children of Israel living together in the Land of Goshen (Genesis 47:27).

There is something more: the escape of more than a tiny group from Egyptian control at the time of Ramesses II seems highly unlikely, as is the crossing of the desert and entry into Canaan. In the thirteenth century, Egypt was at the peak of its authority—the dominant power in the world. The Egyptian grip over Canaan was firm; Egyptian strongholds were built in various places in the country, and Egyptian officials administered the affairs of the region. In the el-Amarna letters, which are dated a century before, we are told that a unit of fifty Egyptian soldiers was big enough to pacify unrest in Canaan. And throughout the period of the New Kingdom, large Egyptian armies marched through Canaan to the north, as far as the Euphrates in Syria. Therefore, the main overland road that went from the delta along the coast of northern Sinai to Gaza and then into the heart of Canaan was of utmost importance to the pharaonic regime.

The most potentially vulnerable stretch of the road—which crossed the arid and dangerous desert of northern Sinai between the delta and Gaza—was the most protected. A sophisticated system of Egyptian forts, granaries, and wells was established at a day’s march distance along the entire length of the road, which was called the Ways of Horus. These road stations enabled the imperial army to cross the Sinai peninsula conveniently and efficiently when necessary. The annals of the great Egyptian conqueror Thutmose III tell us that he marched with his troops from the eastern delta to Gaza, a distance of about 250 kilometers, in ten days. A relief from the days of Ramesses II’s father, Pharaoh Seti I (from around 1300 BCE), shows the forts and water reservoirs in the form of an early map that traces the route from the eastern delta to the southwestern border of Canaan (Figure 7). The remains of these forts were uncovered in the course of archaeological investigations in northern Sinai by Eliezer Oren of Ben-Gurion University, in the 1970s. Oren discovered that each of these road stations, closely corresponding to the sites designated on the ancient Egyptian relief, comprised three elements: a strong fort made of bricks in the typical Egyptian military architecture, storage installations for food provisions, and a water reservoir.

Figure 7: A relief from the time of Pharaoh Seti I (ca. 1300 BCE). Engraved on a wall in the temple of Amun at Karnak, the relief depicts the international road from Egypt to Canaan along the northern coast of the Sinai Peninsula. Egyptian forts with water reservoirs are designated in the lower register.

Putting aside the possibility of divinely inspired miracles, one can hardly accept the idea of a flight of a large group of slaves from Egypt through the heavily guarded border fortifications into the desert and then into Canaan in the time of such a formidable Egyptian presence. Any group escaping Egypt against the will of the pharaoh would have easily been tracked down not only by an Egyptian army chasing it from the delta but also by the Egyptian soldiers in the forts in northern Sinai and in Canaan.

Indeed, the biblical narrative hints at the danger of attempting to flee by the coastal route. Thus the only alternative would be to turn into the desolate wastes of the Sinai peninsula. But the possibility of a large group of people wandering in the Sinai peninsula is also contradicted by archaeology.

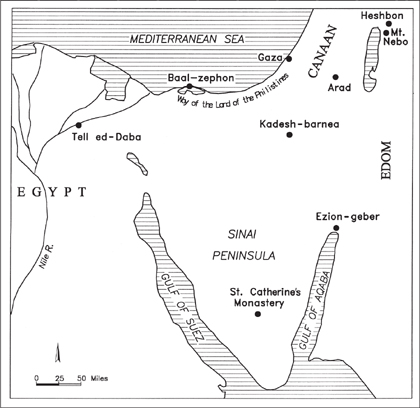

According to the biblical account, the children of Israel wandered in the desert and mountains of the Sinai peninsula, moving around and camping in different places, for a full forty years (Figure 8). Even if the number of fleeing Israelites (given in the text as six hundred thousand) is wildly exaggerated or can be interpreted as representing smaller units of people, the text describes the survival of a great number of people under the most challenging conditions. Some archaeological traces of their generation-long wandering in the Sinai should be apparent. However, except for the Egyptian forts along the northern coast, not a single campsite or sign of occupation from the time of Ramesses II and his immediate predecessors and successors has ever been identified in Sinai. And it has not been for lack of trying. Repeated archaeological surveys in all regions of the peninsula, including the mountainous area around the traditional site of Mount Sinai, near Saint Catherine’s Monastery (see Appendix B), have yielded only negative evidence: not even a single sherd, no structure, not a single house, no trace of an ancient encampment. One may argue that a relatively small band of wandering Israelites cannot be expected to leave material remains behind. But modern archaeological techniques are quite capable of tracing even the very meager remains of hunter-gatherers and pastoral nomads all over the world. Indeed, the archaeological record from the Sinai peninsula discloses evidence for pastoral activity in such eras as the third millennium BCE and the Hellenistic and Byzantine periods. There is simply no such evidence at the supposed time of the Exodus in the thirteenth century BCE.

Figure 8: The Sinai Peninsula, showing main places mentioned in the Exodus story.

The conclusion—that the Exodus did not happen at the time and in the manner described in the Bible—seems irrefutable when we examine the evidence at specific sites where the children of Israel were said to have camped for extended periods during their wandering in the desert (Numbers 33) and where some archaeological indication—if present—would almost certainly be found. According to the biblical narrative, the children of Israel camped at Kadesh-barnea for thirty eight of the forty years of the wanderings. The general location of this place is clear from the description of the southern border of the land of Israel in Numbers 34. It has been identified by archaeologists with the large and well-watered oasis of Ein el-Qudeirat in eastern Sinai, on the border between modern Israel and Egypt. The name Kadesh was probably preserved over the centuries in the name of a nearby smaller spring called Ein Qadis. A small mound with the remains of a Late Iron Age fort stands at the center of this oasis. Yet repeated excavations and surveys throughout the entire area have not provided even the slightest evidence for activity in the Late Bronze Age, not even a single sherd left by a tiny fleeing band of frightened refugees.

Ezion-geber is another place reported to be a camping place of the children of Israel. Its mention in other places in the Bible as a later port town on the northern tip of the Gulf of Aqaba has led to its identification by archaeologists at a mound located on the modern border between Israel and Jordan, halfway between the towns of Eilat and Aqaba. Excavations here in the years 1938–1940 revealed impressive Late Iron Age remains, but no trace whatsoever of Late Bronze occupation. From the long list of encampments in the wilderness, Kadesh-barnea and Ezion-geber are the only ones that can safely be identified, yet they revealed no trace of the wandering Israelites.

And what of other settlements and peoples mentioned in the account of the Israelites’ wanderings? The biblical narrative recounts how the Canaanite king of Arad, “who dwelt in the Negeb,” attacked the Israelites and took some of them captive—enraging them to the point that they appealed for divine assistance to destroy all the Canaanite cities (Numbers 21:1–3). Almost twenty years of intensive excavations at the site of Tel Arad east of Beersheba have revealed remains of a great Early Bronze Age city, about twenty-five acres in size, and an Iron Age fort, but no remains whatsoever from the Late Bronze Age, when the place was apparently deserted. The same holds true for the entire Beersheba valley. Arad simply did not exist in the Late Bronze Age.

The same situation is evident eastward across the Jordan, where the wandering Israelites were forced to do battle at the city of Heshbon, capital of Sihon, king of the Amorites, who tried to block the Israelites from passing in his territory on their way to Canaan (Numbers 21:21–25; Deuteronomy 2:24–35; Judges 11:19–21). Excavations at Tel Hesban south of Amman, the location of ancient Heshbon, showed that there was no Late Bronze city, not even a small village there. And there is more here. According to the Bible, when the children of Israel moved along the Transjordanian plateau they met and confronted resistance not only in Moab but also from the full-fledged states of Edom and Ammon. Yet we now know that the plateau of Transjordan was very sparsely inhabited in the Late Bronze Age. In fact, most parts of this region, including Edom, which is mentioned as a state ruled by a king in the biblical narrative, were not even inhabited by a sedentary population at that time. To put it simply, archaeology has shown us that there were no kings of Edom there for the Israelites to meet.

The pattern should have become clear by now. Sites mentioned in the Exodus narrative are real. A few were well known and apparently occupied in much earlier periods and much later periods—after the kingdom of Judah was established, when the text of the biblical narrative was set down in writing for the first time. Unfortunately for those seeking a historical Exodus, they were unoccupied precisely at the time they reportedly played a role in the events of the wandering of the children of Israel in the wilderness.

So where does this leave us? Can we say that the Exodus, the wandering, and—most important of all—the giving of the Law on Sinai do not possess even a kernel of truth? So many historical and geographical elements from so many periods may have been embedded in the Exodus story that it is hard to decide on a single unique period in which something like it might have occurred. There is the timeless rhythm of migrations to Egypt in antiquity. There is the specific incident of the Hyksos domination of the delta in the Middle Bronze Age. There are the suggestive parallels to elements of the Ramesside era relating to Egypt—together with the first mention of Israel (in Canaan, not Egypt). Many of the place-names in the book of Exodus, such as the Red Sea (in Hebrew Yam Suph), the river Shihor in the eastern delta (Joshua 13:3), and the Israelites’ stopping place at Pi-ha-hiroth, seem to have Egyptian etymologies. They are all related to the geography of the Exodus, but they give no clear indication that they belong to a specific period in Egyptian history.

The historical vagueness of the Exodus story includes the fact that there is no mention by name of any specific Egyptian New Kingdom monarch (while later biblical materials do mention pharaohs by their names, for example Shishak and Necho). The identification of Ramesses II as the pharaoh of the Exodus came as the result of modern scholarly assumptions based on the identification of the place-name Pi-Ramesses with Raamses (Exodus 1:11; 12:37). But there are few indisputable links to the seventh century BCE. Beyond a vague reference to the Israelites’ fear of taking the coastal route, there is no mention of the Egyptian forts in northern Sinai or their strongholds in Canaan. The Bible may reflect New Kingdom reality, but it might just as well reflect later conditions in the Iron Age, closer to the time when the Exodus narrative was put in writing.

And that is precisely what the Egyptologist Donald Redford has suggested. The most evocative and consistent geographical details of the Exodus story come from the seventh century BCE, during the great era of prosperity of the kingdom of Judah—six centuries after the events of the Exodus were supposed to have taken place. Redford has shown just how many details in the Exodus narrative can be explained in this setting, which was also Egypt’s last period of imperial power, under the rulers of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty.

The great kings of that dynasty, Psammetichus I (664–610 BCE) and his son Necho II (610–595 BCE), modeled themselves quite consciously on Egypt’s far more ancient pharaohs. They were active in building projects throughout the delta in an attempt to restore the faded glories of their state and increase its economic and military power. Psammetichus established his capital in Sais in the western delta (thus the name Saite as an alternative for the Twenty-sixth Dynasty). Necho was engaged in an even more ambitious public works project in the eastern delta: cutting a canal through the isthmus of Suez in order to connect the Mediterranean with the Red Sea through the easternmost tributaries of the Nile. Archaeological exploration of the eastern delta has revealed the initiation of some of these extraordinary building activities by the Saite Dynasty—and the presence of large numbers of foreign settlers there.

In fact, the era of the Saite Dynasty provides us with one of the best historical examples for the phenomenon of foreigners settling in the delta of the Nile. In addition to Greek commercial colonies, which were established there from the second half of the seventh century BCE, many migrants from Judah were present in the delta, forming a large community by the early sixth century BCE (Jeremiah 44:1; 46:14). In addition, the public works initiated in this period mesh well with the details of the Exodus account. Though a site carrying the name Pithom is mentioned in a late thirteenth century BCE text, the more famous and prominent city of Pithom was built in the late seventh century BCE. Inscriptions found at Tell Maskhuta in the eastern delta led archaeologists to identify this site with the later Pithom. Excavations there revealed that except for a short occupation in the Middle Bronze Age, it was not settled until the time of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty, when a significant city developed there. Likewise, Migdol (mentioned in Exodus 14:2) is a common title for a fort in the time of the New Kingdom, but a specific, very important Migdol is known in the eastern delta in the seventh century BCE. It is not a coincidence that the prophet Jeremiah, who lived in the late seventh and early sixth centuries BCE, tells us (44:1; 46:14) about Judahites living in the delta, specifically mentioning Migdol. Finally, the name Goshen—for the area where the Israelites settled in the eastern delta (Genesis 45:10)—is not an Egyptian name but a Semitic one. Starting with the seventh century BCE the Qedarite Arabs expanded to the fringe of the settled lands of the Levant, and in the sixth century reached the delta. Later, in the fifth century, they became a dominant factor in the delta. According to Redford, the name Goshen derives from Geshem—a dynastic name in the Qedarite royal family.

A seventh century BCE background is also evident in some of the peculiar Egyptian names mentioned in the Joseph story. All four names—Zaphenath-paneah (the grand vizier of the pharaoh), Potiphar (a royal officer), Potiphera (a priest), and Asenath (Potiphera’s daughter), though used occasionally in earlier periods of Egyptian history, achieve their greatest popularity in the seventh and sixth centuries BCE. An additional seemingly incidental detail seems to clinch the case for the biblical story having integrated many details from this specific period: the Egyptian fear of invasion from the east. Egypt was never invaded from that direction before the attacks by Assyria in the seventh century. Yet in the Joseph story, dramatic tension is heightened when he accuses his brothers, newly arrived from Canaan, of being spies who “come to see the weakness of the land” (Genesis 42:9). And in the Exodus story, the pharaoh fears that the departing Israelites will collaborate with an enemy. These dramatic touches would make sense only after the great age of Egyptian power of the Ramesside period, against the background of the invasions of an Egypt greatly weakened by the Assyrians, Babylonians, and Persians in the seventh and sixth centuries.

Lastly, all the major places that play a role in the story of the wandering of the Israelites were inhabited in the seventh century; in some cases they were occupied only at that time. A large fort was established at Kadeshbarnea in the seventh century. There is a debate about the identity of the builders of the fort—whether it served as a far southern outpost of the kingdom of Judah on the desert routes in the late seventh century or was built in the early seventh century under Assyrian auspices. Yet in either case the site so prominent in the Exodus narrative as the main camping place of the Israelites was an important and perhaps famous desert outpost in the late monarchic period. The southern port city of Ezion-geber also flourished at this time. Likewise, the kingdoms of Transjordan were populous, well-known localities in the seventh century. Most relevant is the case of Edom. The Bible describes how Moses sent emissaries from Kadesh-barnea to the king of Edom to ask permission to pass through his territory on the way to Canaan. The king of Edom refused to grant the permission and the Israelites had to bypass his land. According to the biblical narrative, then, there was a kingdom in Edom at that time. Archaeological investigations indicate that Edom reached statehood only under Assyrian auspices in the seventh century BCE. Before that period it was a sparsely settled fringe area inhabited mainly by pastoral nomads. No less important, Edom was destroyed by the Babylonians in the sixth century BCE, and sedentary activity there recovered only in Hellenistic times.

All these indications suggest that the Exodus narrative reached its final form during the time of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty, in the second half of the seventh and the first half of the sixth century BCE. Its many references to specific places and events in this period quite clearly suggest that the author or authors integrated many contemporary details into the story. (It was in much the same way that European illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages depicted Jerusalem as a European city with turrets and battlements in order to heighten its direct impact on contemporary readers.) Older, less formalized legends of liberation from Egypt could have been skillfully woven into the powerful saga that borrowed familiar landscapes and monuments. But can it be just a coincidence that the geographical and ethnic details of both the patriarchal origin stories and the Exodus liberation story bear the hallmarks of having been composed in the seventh century BCE? Were there older kernels of historical truth involved, or were the basic stories first composed then?

It is clear that the saga of liberation from Egypt was not composed as an original work in the seventh century BCE. The main outlines of the story were certainly known long before, in the allusions to the Exodus and the wandering in the wilderness contained in the oracles of the prophets Amos (2:10; 3:1; 9:7) and Hosea (11:1 13:4) a full century before. Both shared a memory of a great event in history that concerned liberation from Egypt and took place in the distant past. But what kind of memory was it?

The Egyptologist Donald Redford has argued that the echoes of the great events of the Hyksos occupation of Egypt and their violent expulsion from the delta resounded for centuries, to become a central, shared memory of the people of Canaan. These stories of Canaanite colonists established in Egypt, reaching dominance in the delta and then being forced to return to their homeland, could have served as a focus of solidarity and resistance as the Egyptian control over Canaan grew tighter in the course of the Late Bronze Age. As we will see, with the eventual assimilation of many Canaanite communities into the crystallizing nation of Israel, that powerful image of freedom may have grown relevant for an ever widening community. During the time of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah, the Exodus story would have endured and been elaborated as a national saga—a call to national unity in the face of continual threats from great empires.

It is impossible to say whether or not the biblical narrative was an expansion and elaboration of vague memories of the immigration of Canaanites to Egypt and their expulsion from the delta in the second millennium BCE. Yet it seems clear that the biblical story of the Exodus drew its power not only from ancient traditions and contemporary geographical and demographic details but even more directly from contemporary political realities.

The seventh century was a time of great revival in both Egypt and Judah. In Egypt, after a long period of decline and difficult years of subjection to the Assyrian empire, King Psammetichus I seized power and transformed Egypt into a major international power again. As the rule of the Assyrian empire began to crumble, Egypt moved in to fill the political vacuum, occupying former Assyrian territories and establishing permanent Egyptian rule. Between 640 and 630 BCE, when the Assyrians withdrew their forces from Philistia, Phoenicia, and the area of the former kingdom of Israel, Egypt took over most of these areas, and political domination by Egypt replaced the Assyrian yoke.

In Judah, this was the time of King Josiah. The idea that YHWH would ultimately fulfill the promises given to the patriarchs, to Moses, and to King David—of a vast and unified people of Israel living securely in their land—was a politically and spiritually powerful one for Josiah’s subjects. It was a time when Josiah embarked on an ambitious attempt to take advantage of the Assyrian collapse and unite all Israelites under his rule. His program was to expand to the north of Judah, to the territories where Israelites were still living a century after the fall of the kingdom of Israel, and to realize the dream of a glorious united monarchy: a large and powerful state of all Israelites worshiping one God in one Temple in one capital—Jerusalem—and ruled by one king of Davidic lineage.

The ambitions of mighty Egypt to expand its empire and of tiny Judah to annex territories of the former kingdom of Israel and establish its independence were therefore in direct conflict. Egypt of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty, with its imperial aspirations, stood in the way of the fulfillment of Josiah’s dreams. Images and memories from the past now became the ammunition in a national test of will between the children of Israel and the pharaoh and his charioteers.

We can thus see the composition of the Exodus narrative from a striking new perspective. Just as the written form of the patriarchal narratives wove together the scattered traditions of origins in the service of a seventh century national revival in Judah, the fully elaborated story of conflict with Egypt—of the great power of the God of Israel and his miraculous rescue of his people—served an even more immediate political and military end. The great saga of a new beginning and a second chance must have resonated in the consciousness of the seventh century’s readers, reminding them of their own difficulties and giving them hope for the future.

Attitudes towards Egypt in late monarchic Judah were always a mixture of awe and revulsion. On one hand, Egypt had always provided a safe haven in time of famine and an asylum for runaways, and was perceived as a potential ally against invasions from the north. At the same time there had always been suspicion and animosity toward the great southern neighbor, whose ambitions from earliest times were to control the vital overland passage through the land of Israel northward to Asia Minor and Mesopotamia. Now a young leader of Judah was prepared to confront the great pharaoh, and ancient traditions from many different sources were crafted into a single sweeping epic that bolstered Josiah’s political aims.

New layers would be added to the Exodus story in subsequent centuries—during the exile in Babylonia and beyond. But we can now see how the astonishing composition came together under the pressure of a growing conflict with Egypt in the seventh century BCE. The saga of Israel’s Exodus from Egypt is neither historical truth nor literary fiction. It is a powerful expression of memory and hope born in a world in the midst of change. The confrontation between Moses and pharaoh mirrored the momentous confrontation between the young King Josiah and the newly crowned Pharaoh Necho. To pin this biblical image down to a single date is to betray the story’s deepest meaning. Passover proves to be not a single event but a continuing experience of national resistance against the powers that be.