The archaeological evidence also reveals that the Omrides far surpassed any other monarchs in Israel or Judah as builders and administrators. In a sense, theirs was the first golden age of the Israelite kings. Yet in the Bible, the description of the Omride kingdom is quite sketchy. Except for the mention of elaborate palaces in Samaria and Jezreel, there is almost no reference to the size, scale, and opulence of their realm. In the early twentieth century, archaeology first began to make a significant contribution, as major excavations at the site of Omri’s capital city, Samaria, got under way. There is hardly a doubt that Samaria was indeed built by Omri, since later Assyrian sources call the northern kingdom “the house of Omri,” an indication that he was the founder of its capital. The site, first excavated in 1908–10 by an expedition of Harvard University, was further explored in the 1930s by a joint American, British, and Jewish–Palestinian team. That site further revealed the splendor of the Omride dynasty.

The site of Samaria is, even today, impressive. Located in the midst of gently rolling hills, planted with olive and almond orchards, it overlooks a rich agricultural region. The discovery of some pottery sherds, a few walls, and a group of rock-cut installations indicated that it was already inhabited before the arrival of Omri; there seems to have been a small, poor Israelite village or a farm there in the eleventh and tenth centuries BCE. This may perhaps be the inheritance of Shemer, the original owner of the property mentioned in 1 Kings 16:24. In any case, with the arrival of Omri and his court around 880 BCE, the farm buildings were leveled and an opulent palace with auxiliary buildings for servants and court personnel arose on the summit of the hill.

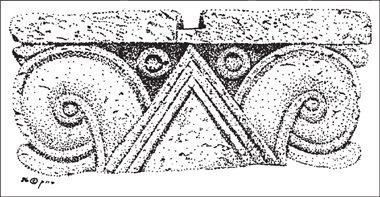

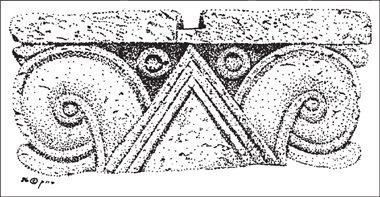

Figure 21: A Proto-Aeolic capital. Courtesy of the Israel Exploration Society.

Samaria was apparently conceived from the start as the personal capital of the Omride dynasty. It was the most grandiose architectural manifestation of the rule of Omri and Ahab (Figure 20:1, p. 179). Located on a small hilltop, however, it was not the ideal place for a vast royal compound. The builders’ solution to this problem—a daring innovation in Iron Age Israel—was to carry out massive earthmoving operations to create a huge, artificial platform on the summit of the hill. An enormous wall (constructed of linked rooms, or casemates) was build around the hill, framing the summit and the upper slopes in a large rectangular enclosure. When that retaining wall was completed, construction gangs filled its interior with thousands of tons of earth hauled from the vicinity.

The scale of this project was enormous. The earthen fill packed behind the supporting wall was, in some places, almost twenty feet deep. That was probably why the enclosure wall surrounding and supporting the palace complex was built in the casemate technique: the casemate chambers (which were also filled with earth) were designed to relieve the immense pressure of the fill. A royal acropolis of five acres was thus created. This huge stone and earth construction can be compared in audacity and extravagance (though perhaps not in size) only to the work that Herod the Great carried out almost a millennium later on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem.

Rising on one side of this artificial platform was an exceptionally large and beautiful palace, which in scale and grandeur rivaled the contemporary palaces of the states in northern Syria. Although the Omride palace at Samaria has been only partially excavated, enough of its plan has been uncovered to recognize that the central building alone covered an area of approximately half an acre. With its outer walls built entirely of finely hewn and closely fitted ashlar stones, it is the largest and most beautiful Iron Age building ever excavated in Israel. Even the architectural ornamentation was exceptional. Stone capitals of a unique early style, called Proto-Aeolic (because of the resemblance to the later Greek Aeolic style), were found in the rubble of later centuries’ accumulations (Figure 21). These ornate stone capitals probably adorned the monumental outer gate to the compound, or perhaps an elaborate entrance into the main palace itself. Of the interior furnishings little remained except for a number of intricately carved ivory plaques, probably dating from the eighth century BCE and bearing Syro-Phoenician and Egyptian motifs. These ivories, used as inlays on the palace furniture, might explain the allusion in 1 Kings 22:39 to the ivory house that Ahab reportedly built.

Figure 22: The eighth century BCE at Megiddo. The six-chambered gate (ascribed by Yadin to a “Solomonic” level) most probably belongs to this stratum. Courtesy Prof. David Ussishkin, Tel Aviv University.

Several administrative buildings surrounded the palace, but most of the enclosure was left open. The simple houses of the people of Samaria apparently clustered on the slopes beneath the acropolis. For visitors, traders, and official emissaries arriving at Samaria, the visual impression of the Omrides’ royal city must have been stunning. Its elevated platform and huge, elaborate palace bespoke wealth, power, and prestige.

Samaria was only the beginning of the discovery of Omride grandeur. Megiddo came next. In the mid-1920s, the University of Chicago team uncovered an Iron Age palace built of beautifully dressed ashlar blocks. The first director of the Oriental Institute excavations at Megiddo, Clarence S. Fisher, had also worked at Samaria and was immediately impressed by the similarity of construction. He was supported in this observation by John Crowfoot, the leader of the Joint Expedition to Samaria, who suggested that the similarity of building techniques and overall plan at Samaria and Megiddo indicated that both were built under Omride patronage. But this matter of architectural similarity was not fully pursued for many decades. The members of the University of Chicago team were more interested in the glory of Solomon than in the wicked Omrides. They ignored the similarity of the Megiddo and Samaria building styles and dated the complexes of pillared buildings (presumably stables) in the succeeding stratum to the days of the united monarchy. In the early 1960s, when Yigael Yadin of the Hebrew University came to Megiddo, he dated the Megiddo palaces—the one excavated in the 1920s and one he himself uncovered—to the time of Solomon and linked the later level containing the stables and other structures to the era of the Omrides.

That city was certainly impressive (Figure 22). It was surrounded by a massive fortification and, according to Yadin, furnished with a large four-chambered city gate (built directly on top of the earlier “Solomonic” gate). The most dominant features inside the city were the two sets of pillared buildings that had long before been identified as stables. Yet Yadin did not link them to the biblical descriptions of Solomon’s great chariot army but to that of Ahab, noted in the Shalmaneser inscription. Yet as we will see, Yadin had not correctly identified Ahab’s city; those stables probably belonged to another, even later Israelite king.

The northern city of Hazor, which Yadin excavated in the 1950s and 1960s, provided additional apparent evidence of Omride splendor. Hazor was also surrounded by a massive fortification. In the center of that city Yadin uncovered a pillared building somewhat similar in form to the Megiddo stables, divided into three long aisles by rows of stone pillars. But this structure contained no stone troughs for feeding, so it was accordingly interpreted as a royal storehouse. An imposing citadel was uncovered on the eastern, narrow tip of the mound, enclosed by the massive city wall.

Another important site connected with the Omrides is the city of Dan in the far north at the headwaters of the Jordan River. We have already cited the opening lines of the stele erected at Dan by Hazael, king of Aram-Damascus, noting that the Omrides had previously taken that area from the Arameans. The excavations at Dan, directed by Abraham Biran, of the Hebrew Union College, uncovered massive Iron Age fortifications, a huge, elaborate city gate, and a sanctuary with a high place. This large podium, measuring about sixty feet on a side, and built of beautifully dressed ashlar stones, has been dated with the city’s other monumental structures to the time of the Omrides.

Yet perhaps the most impressive engineering achievements initially linked to the Omrides are the enormous underground water tunnels cut through the bedrock beneath the cities of Megiddo and Hazor. These tunnels provided the city’s inhabitants with secure access to drinking water even in times of siege. In the ancient Near East this was a critical challenge, for while important cities were surrounded by elaborate fortifications to allow them to withstand an attack or siege by even the most determined enemy, they seldom had a source of freshwater within their city walls. The inhabitants could always collect rainwater in cisterns, but this would not be sufficient when a siege extended through the hot, rainless months of summer—especially if the population of the city had swelled with refugees.

Since most ancient cities were located near springs, the challenge was to devise safe access to them. The rock-cut water tunnels at Hazor and Megiddo are among the most elaborate solutions to this problem. At Hazor, a large vertical shaft was cut through the remains of earlier cities into the solid rock below. Because of its enormous depth, of almost a hundred feet, support walls had to be constructed to prevent collapse. Broad steps led to the bottom, where a sloping tunnel, some eighty feet long, led into a pool-like rock-cut chamber into which groundwater seeped. One can only imagine a procession of water bearers threading their way single-file down the stairs and the length of the subterranean tunnel to fill their jars in the dark cavern and returning up to the streets of the besieged city with water to keep its people alive.

Figure 23: A cross-section of the Megiddo water system

The Megiddo water system (Figure 23) consisted of a somewhat simpler shaft, over a hundred feet in depth, cut through the earlier remains to bedrock. From there it led to a horizontal tunnel, more than two hundred feet long, wide and high enough for a few people to walk at the same time, which led to a natural spring cave on the edge of the mound. The entrance to the cave from outside was blocked and camouflaged. Yadin dated both the Megiddo and Hazor water systems to the time of the Omrides. He proposed to connect the Israelite skill of hewing water systems to a section in the Mesha stele where the Moabite king recounted how he dug a water reservoir in his own capital city with the help of Israelite prisoners of war. It was obvious that the construction of such monumental installations required an enormous investment and efficient state organization—and a high level of technical skill. From a functional point of view, Iron Age engineers could perhaps have reached a similar result with a much smaller investment by simply digging a well into the water table under the mound. But the visual impressiveness of these great water installations certainly enhanced the prestige of the royal authority that commissioned them.

Even though early and mid-twentieth century archaeologists assigned many magnificent building projects to the Omrides, the period of their rule over the kingdom of Israel was never seen as a particularly formative moment in biblical history. Colorful, yes. Vivid, to be sure. But in purely historical terms, the story of the Omrides—of Ahab and Jezebel—seemed to be spelled out in quite adequate detail in the Bible, with supporting information from Assyrian, Moabite, and Aramean texts. There seemed to be so many more intriguing historical questions to be answered by excavation and further research: the precise process of the Israelite settlement; the political crystallization of the monarchy under David and Solomon; or even the underlying causes of the eventual Assyrian and Babylonian conquests in the land of Israel. Omride archaeology was usually considered just a sidelight on the main agenda of biblical archaeology, given less attention than the Solomonic period.

But there was something seriously wrong with this initial correlation between biblical history and archaeological finds. The new questions that began to be asked about the nature, extent, or even historical existence of Solomon’s vast kingdom—and the redating of the archaeological layers—inevitably affected the scholarly understanding of the Omrides as well. For if Solomon had not actually built the “Solomonic” gates and palaces, who did? The Omrides were the obvious candidates. The earliest architectural parallels to the distinctive palaces dug at Megiddo (and initially attributed to Solomon) came from northern Syria—the supposed place of origin of this type—in the ninth century BCE, a full century after the time of Solomon! This was precisely the time of the Omrides’ rule.

The clinching clue to a redating of the “Solomonic” gates and palaces came from the biblical site of Jezreel, located less than ten miles to the east of Megiddo in the heart of the Jezreel valley. The site is located in a beautiful elevated spot, enjoying a mild climate in the winter and a cool breeze in the summer and commanding a sweeping panorama of the entire Jezreel valley and the hills surrounding it, from Megiddo in the west through Galilee in the north, to Beth-shean and the Gilead in the east. Jezreel is famous largely due to the biblical story of Naboth’s vineyard, and Ahab and Jezebel’s plans for palace expansion, and as the scene of the bloody, final liquidation of the Omride dynasty. In the 1990s the site was excavated by David Ussishkin of Tel Aviv University and John Woodhead of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem. They uncovered a large royal enclosure, very similar to that of Samaria (Figure 20:3, p. 179). This impressive compound was occupied for only a brief period in the ninth century BCE—presumably only during the reign of the Omride Dynasty—and was destroyed shortly after its construction, perhaps in connection with the fall of the Omrides or the subsequent invasions of northern Israel by the armies of Aram-Damascus.

As in Samaria, an enormous casemate wall built around the original hill at Jezreel formed a “box” to be filled with many tons of earth. As a result of large-scale filling and leveling operations, a level podium was created on which the inner structures of the royal compound were built. At Jezreel the archaeologists discovered other striking elements of a hitherto unrecognized Omride architectural style. A sloping earthen rampart supported the casemate wall on the outside to prevent it from collapsing. As an additional defensive element, the compound was surrounded by a formidable moat dug in the bedrock, at least twenty-five feet wide and more than fifteen feet deep. The entrance to the Omride royal enclosure at Jezreel was provided by a gate, probably of the six-chamber type.

Because Jezreel was chronologically restricted to a brief occupation in the ninth century BCE, it offered a unique case where the distinctive styles of pottery found within it could be used as a clear dating indicator for the Omride period at other sites. Significantly, the pottery styles uncovered in the Jezreel enclosure were almost identical to those found in the level of the “Solomonic” palaces of Megiddo. It was thus becoming quite evident, from both architectural and ceramic standpoints, that the Omrides—not Solomon—had constructed the ashlar buildings at Megiddo, in addition to the Jezreel and Samaria compounds.

The hypothesis that the Omrides, not Solomon, established the first fully developed monarchy in Israel grew more convincing with a new look at the evidence from the other major cities of the kingdom of Israel. At Hazor, Yadin had identified a triangular compound on the acropolis—surrounded by a casemate wall and entered through a six-chambered gate—as the city established by Solomon in the tenth century BCE. The redating of the pottery on the basis of the Jezreel discoveries would place this city level in the early ninth century BCE. Indeed, there was an unmistakable structural resemblance to the palace compounds in Samaria and Jezreel (Figure 20:2, p. 179). Although the triangular shape of the Hazor compound was dictated by the topography of the site, its construction involved a massive leveling and filling operation that raised the level of the gate area in relation to the outside area to its east. A colossal moat, estimated to be 150 feet wide and over thirty feet deep, was dug outside the casemate wall. The overall similarity to Jezreel and Samaria is clear. Thus, another city long believed to be Solomonic is likely Omride.

Evidence of the extent of Omride building projects emerges from a closer analysis of the remains at Megiddo and Gezer. Although Megiddo has no casemate compound, the two beautiful palaces on its summit that were built of distinctive ashlar masonry recall the building techniques used at Samaria (Figure 24). The resemblance is particularly strong in the case of the southernmost palace at Megiddo, which was built at the edge of a large courtyard, in the style of a north Syrian bit hilani palace, covering an area of about sixty-five by a hundred feet. Two exceptionally large Proto-Aeolic capitals (like those used in Samaria) were found in the vicinity of the gate leading into the palace’s compound, and they may have decorated the entrance to the palace itself. Norma Franklin of the current Megiddo expedition identified another similarity: the southern palace at Megiddo and the palace at Samaria are the only Iron Age buildings in Israel whose ashlar blocks share a specific type of masons’ marks. A second palace, which was partially uncovered by Yadin on the northern edge of the mound—and is now being fully unearthed by the new expedition to Megiddo—is also built of ashlar in the north Syrian palace style.

Figure 24: The Omride city at Megiddo

The evidence at Gezer is perhaps the most fragmentary of all the supposed Solomonic cities, but enough has been found to indicate a similarity to the other Omride sites. A six-chambered gate built of fine masonry, with ashlars at the jambs and connected to a casemate wall, was discovered on the southern edge of the site. The construction of the gate and the casemate wall involved the leveling of a terrace on the hillside and the import of a massive fill. In addition, fragmentary walls indicate that a large building, possibly an ashlar palace, was built on the northwestern side of the mound. It too may have been decorated with distinctive Proto-Aeolic capitals that were found at Gezer in the beginning of the twentieth century.

These five sites offer a glimpse at the royal architecture of Israel’s Omride golden age. In addition to the artificial platforms for palace compounds of varying sizes and scale, the compounds—at least at Samaria, Jezreel, and Hazor—seem to have been largely empty, except for the specialized administrative buildings and royal palaces. Fine ashlar stones and Proto-Aeolic capitals were distinctive decorative elements in these sites. The main entrances to the royal compounds seem to have been guarded by six-chambered gates, and in some cases the compounds were surrounded by a moat and a glacis.1

Archaeologically and historically, the redating of these cities from Solomon’s era to the time of the Omrides has enormous implications. It removes the only archaeological evidence that there was ever a united monarchy based in Jerusalem and suggests that David and Solomon were, in political terms, little more than hill country chieftains, whose administrative reach remained on a fairly local level, restricted to the hill country. More important, it shows that despite the biblical emphasis on the uniqueness of Israel, a highland kingdom of a thoroughly conventional Near Eastern type arose in the north in the early ninth century BCE.

It is now possible to search for additional examples of Omride cities in more distant places, far beyond the traditional tribal inheritances of Israel. The Mesha stele reported that Omri built two cities in Moab, Ataroth and Jahaz, probably as his southern border strongholds in Transjordan (Figure 16, p. 136). Both are also mentioned in various geographical lists in the Bible, with Ataroth identified with the still unexcavated site of Khirbet Atarus southwest of the modern Jordanian town of Madaba. Jahaz is more difficult to identify. It is mentioned a few times in the Bible as being located on the desert fringe near the Arnon, the deep, winding canyon that runs through the heartland of Moab—from the eastern desert to its outlet in the Dead Sea. The Omrides seem to have extended their rule to this region. And on the northern bank of the Arnon is a remote Iron Age ruin called Khirbet el-Mudayna that contains all the features we have described as being typical of Omride architecture.

The site, now being excavated by P.M. Michèle Daviau, of the Wilfrid Laurier University in Canada, consists of a large fortress built on an elongated hill. A casemate wall encloses an area of about two and a half acres and is entered through a six-chambered gate. Defensive features include a sloping earthen rampart and a moat. Inside the compound are remains of a monumental building, including collapsed ashlars. Aerial photographs of the site hint that the entire complex was based on an artificial podium fill. The pioneering explorer of Jordan, Nelson Glueck, who visited the site in the 1930s, was so impressed with the compound’s features that he compared it to the immense and famous Maiden Castle Iron Age hill fort in England.

Is it possible that this remote ruin is the ancient Omride outpost of Jahaz mentioned in the Mesha stele? Could it be that in the building of this remote border fort the Omride engineers and architects utilized the typical characteristics of their great construction projects in the northern kingdom west of the Jordan? Is it possible that as in the case of Samaria and Jezreel, they employed sophisticated earthmoving operations and huge retaining walls to turn a small hilltop settlement into an imposing stronghold? Perhaps the Omrides were even more powerful—and their cultural influence even more far-reaching—than is currently recognized.2

Where did the power and wealth to establish and maintain this full-fledged kingdom come from? What development in the northern hill country led to the emergence of the Omride state? We have already mentioned how the relatively limited resources and sparse population of Judah would have made it quite unlikely that David could have achieved vast territorial conquests or that his son Solomon would have been able to administer large territories. But as we have also mentioned, the resources of the northern hill country were much richer and its population was relatively large. With the destruction of the Canaanite centers in the lowlands, possibly during the raid of Shishak at the end of the tenth century BCE, any potential northern strongman would have been able to gain control of the fertile valleys of the north as well. That fits with what we see in the pattern of the most prominent Omride archaeological remains. In expanding from the original hill country domain of the northern kingdom of Israel to the heart of former Canaanite territory at Megiddo, Hazor, and Gezer, and into the territories of southern Syria and Transjordan, the Omrides fulfilled the centuries-old dream of the rulers of the hill country of establishing a vast and diverse territorial state controlling rich agricultural lands and bustling international trade routes. It was also—of necessity—a multiethnic society.

The northern kingdom of Israel joined the Samarian highlands with the northern valleys, integrating several different ecosystems and a heterogeneous population into its state. The highlands of Samaria—the core territory of the state and the seat of the capital—were inhabited by village communities that would have identified themselves culturally and religiously as Israelites. In the northern lowlands—the Jezreel and the Jordan valleys—the rural population was comprised mainly of settled peasant villages that had been for centuries closely linked to the Canaanite city-states. Farther north were villages more closely aligned to the Aramean culture of Syria and to the Phoenicians of the coast.

In particular, the large and vibrant Canaanite population that endured in the north had to be integrated into the administrative machinery of any full-fledged state. Even before the recent archaeological discoveries, the unique demographic mix of the population of the northern kingdom, especially the relationship between Israelites and Canaanites, did not escape the attention of biblical scholars. On the basis of the biblical accounts of religious turmoil within the Omride kingdom, the German scholar Albrecht Alt suggested that the Omrides had developed a system of dual rule from their two main capitals, with Samaria functioning as a center for the Canaanite population and Jezreel serving as the capital for the northern Israelites. The recent archaeological and historical findings indicate exactly the opposite. The Israelite population was actually concentrated in the hill country around Samaria, while Jezreel, in the heart of the fertile valley, was situated in a region of clear Canaanite cultural continuity. Indeed, the remarkable stability in settlement patterns and the unchanging layout of small villages in the Jezreel Valley are clear indications that the Omrides did not shake the Canaanite rural system in the northern lowlands.

For the Omrides, the task of political integration was especially pressing since competing states were emerging at the same time in neighboring Damascus, Phoenicia, and Moab—each with powerful cultural claims on population groups on the borders with Israel. The early ninth century was therefore the time when national and even some sort of territorial boundaries had to be defined. Thus the Omrides’ construction of impressive fortified compounds, some of them with palatial quarters, in the Israelite heartland, in the Jezreel valley, on the border with Aram-Damascus, and even further afield should be seen as serving both administrative necessities and royal propaganda. The British biblical scholar Hugh Williamson characterized them as visual displays of the power and prestige of the Omride state, aimed to impress, awe, and even intimidate the population both at home and along new frontiers.

Of all the resources that the Omrides had at their disposal, heterogeneous population was perhaps the most important of all—for agriculture, building activities, and war. Although it is difficult to estimate the ninth century population of the kingdom of Israel with great precision, large-scale surveys in the region indicate that by the eighth century BCE—a century after the Omrides—the population of the northern kingdom may have reached about 350,000. At that time, Israel was surely the most densely populated state in the Levant, with far more inhabitants than Judah, Moab, or Ammon. Its only possible rival was the kingdom of Aram-Damascus in southern Syria, which—as we will see in greater detail in the next chapter—bitterly competed with Israel for regional hegemony.

Other positive developments from outside the region greatly benefited the fortunes of the Omride kingdom. Its rise to power coincided with the revival of the eastern Mediterranean trade, and the harbor cities of Greece, Cyprus, and the Phoenician coast were once again strongly involved in maritime commerce. The strong Phoenician artistic influence on Israelite culture, the sudden appearance of large quantities of Cypro-Phoenician-style vessels in the cities of the kingdom of Israel, and—not coincidentally—the biblical testimony that Ahab married a Phoenician princess all seem to indicate that Israel was an active participant in this economic revival as a supplier of valuable agricultural products and a master over some of the most important overland trade routes of the Levant.

Thus the Omride idea of a state covering large territories of both highlands and lowlands in certain ways revived ideas, practices, and material culture of Bronze Age Canaan, in the centuries before the rise of Israel. In fact, from the conceptual and functional points of view, the great Omride citadels resembled the capitals of the great Canaanite city-states of the Late Bronze Age, which ruled over a patchwork of peoples and lands. Thus from the point of view of both form and function, the layout of Megiddo in the ninth century BCE was not very different from its layout in the Late Bronze Age. Large parts of the mound were devoted to public buildings and open areas, while only limited areas were occupied by domestic quarters. As was the case in Canaanite Megiddo, the urban population constituted mainly the ruling elite, which controlled the rural hinterland. And a similar cultural continuity is exquisitely manifested in the nearby city of Taanach, where a magnificent decorated cult stand from the ninth century BCE bears elaborate motifs drawn from the Canaanite traditions of the Late Bronze Age.

That is why it is difficult to insist, from a strictly archaeological perspective, that the kingdom of Israel as a whole was ever particularly Israelite in either the ethnic, cultural, or religious connotations of that name as we understand it from the perspective of the later biblical writers. The Israeliteness of the northern kingdom was in many ways a late monarchic Judahite idea.

The writer of the books of Kings was concerned to show only that the Omrides were evil and that they received the divine punishment that their sinful arrogant behavior had so richly earned. Of course, he had to recount details and events about the Omrides that were well known through folktales and earlier traditions, but in all of them he wanted to highlight the Omrides’ dark side. Thus he diminished their military might with the story of the Aramean siege of Samaria, which was taken from events of later days, and with the accusation that in a moment of victory Ahab disobeyed a divine command to utterly annihilate his enemy. The biblical author closely linked the grandeur of the palace at Samaria and the majestic royal compound in Jezreel with idolatry and social injustice. He linked the images of the awesome might of Israelite chariots in full battle order with the Omride family’s horrible end. He wanted to delegitimize the Omrides and to show that the entire history of the northern kingdom had been one of sin that led to misery and inevitable destruction. The more Israel had prospered in the past, the more scornful and negative he became about its kings.

The true character of Israel under the Omrides involves an extraordinary story of military might, architectural achievement, and (as far as can be determined) administrative sophistication. Omri and his successors earned the hatred of the Bible precisely because they were so strong, precisely because they succeeded in transforming the northern kingdom into an important regional power that completely overshadowed the poor, marginal, rural-pastoral kingdom of Judah to the south. The possibility that the Israelite kings who consorted with the nations, married foreign women, and built Canaanite-type shrines and palaces would prosper was both unbearable and unthinkable.

Moreover, from the perspective of late monarchic Judah, the internationalism and openness of the Omrides was sinful. To become entangled with the ways of the neighboring peoples was, according to the seventh century Deuteronomistic ideology, a direct violation of divine command. But a lesson could still be learned from that experience. By the time of the compilation of the books of Kings, history’s verdict had already been returned. The Omrides had been overthrown and the kingdom of Israel was no more. Yet with the help of archaeological evidence and the testimony of outside sources, we can now see how the vivid scriptural portraits that doomed Omri, Ahab, and Jezebel to ridicule and scorn over the centuries skillfully concealed the real character of the first true kingdom of Israel.