In order to understand the full story of ancient Israel and the making of biblical history, we cannot stop at Josiah’s death, nor can we halt at the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple and the fall of the Davidic dynasty. It is crucial to examine what happened in Judah in the decades that followed the Babylonian conquest, to survey the developments that occurred among the exiles in Babylon, and to recount the events that took place in post-exilic Jerusalem. In these times and places, the texts of both the Pentateuch and the Deuteronomistic History underwent far-reaching additions and revisions, arriving at what was substantially their final form. Meanwhile the people of Israel developed new modes of communal organization and worship in Babylon and Jerusalem during the sixth and fifth centuries BCE that formed the foundations of Second Temple Judaism and thus of early Christianity. The events and processes that took place in the century and half after the conquest of the kingdom of Judah—as we can reconstruct them from the historical sources and archaeological evidence—are therefore crucial for understanding how the Judeo-Christian tradition emerged.

Before continuing with the biblical story we must take note of the meaningful change in the biblical sources at our disposal. The Deuteronomistic History, which narrated the history of Israel from the end of the wandering in the wilderness to the Babylonian conquest of Jerusalem, ends abruptly. Other biblical authors take over. The situation in Judah after the destruction is described in the book of Jeremiah, while the book of Ezekiel (written by one of the exiles) provides information on the life and expectations of the Judahite deportees in Babylonia. Events that took place when the successive waves of exiles returned to Jerusalem are reported in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah and by the prophets Haggai and Zechariah. This is also the moment in our story when we must change our terminology: the kingdom of Judah becomes Yehud—the Aramaic name of the province in the Persian empire—and the people of Judah, the Judahites, will henceforth be known as Yehudim, or Jews.

This climactic phase of the history of Israel begins with a scene of utter disaster and hopelessness. Jerusalem is destroyed, the Temple is in ruins, the last reigning Davidic king, Zedekiah, is blinded and exiled, his sons slaughtered. Many members of the Judahite elite are deported. The situation has reached a low point and it seems as if the history of the people of Israel has reached a bitter and irreversible end.

Not quite so. From the concluding chapter of 2 Kings and from the book of Jeremiah, we learn that part of the population of Judah had survived and was not deported. The Babylonian authorities even allowed them a measure of autonomy, appointing an official named Gedaliah, the son of Ahikam, to rule over the people who remained in Judah, admittedly “the poorest of the land.” Mizpah, a modest town north of Jerusalem, became the center of Gedaliah’s administration and a haven for other Judahites, like the prophet Jeremiah, who had opposed the ill-fated uprising against Babylonia. Gedaliah tried to persuade the people of Judah to cooperate with the Babylonians and rebuild their lives and future, despite the destruction of the Temple and the city of Jerusalem. But soon Gedaliah was assassinated by Ishmael, the son of Nethaniah, “of the royal family”—possibly because Gedaliah’s cooperation with the Babylonians was viewed as posing a threat to the future hopes of the Davidic house. Other Judahite officials and Babylonian imperial representatives present at Mizpah were also killed. The surviving members of the local population decided to flee for their lives, leaving Judah virtually uninhabited. The people “both small and great” went to Egypt, “for they were afraid of the Chaldeans” (as the Babylonians were also known). The prophet Jeremiah fled with them, bringing to an apparent end centuries of Israelite occupation of the Promised Land (2 Kings 25:22–26; Jeremiah 40:7–43:7).

The Bible provides few details about the life of the exiles during the next fifty years. Our only sources are the indirect and often obscure allusions in various prophetic works. Ezekiel and Second Isaiah (chapters 40–55 in the book of Isaiah) tell us that the Judahite exiles lived both in the capital city of Babylon and in the countryside. The priestly and royal deportees established new lives for themselves, with the exiled Davidic king Jehoiachin—rather than the disgraced and blinded Zedekiah—possibly maintaining some sort of authority over the community. From scattered references in the book of Ezekiel, it seems that the Judahite settlements were placed in undeveloped areas of the Babylonian kingdom, near newly dug canals. Ezekiel, himself an exiled priest of the Jerusalem Temple, lived for a while in a settlement on an ancient mound named Tel-abib (in Hebrew, Tel Aviv; Ezekiel 3:15).

Of the nature of their life, the biblical texts reveal little except to note that the exiles settled in for a long stay, following the advice of Jeremiah: “Build houses and live in them; plant gardens and eat their produce. Take wives and have sons and daughters; take wives for your sons, and give your daughters in marriage, that they may bear sons and daughters; multiply there, and do not decrease” (Jeremiah 29:5–6). But history would soon take a sudden and dramatic turn that would bring many of the exiles back to Jerusalem.

The mighty Neo-Babylonian empire crumbled and was conquered by the Persians in 539 BCE. In the first year of his reign, Cyrus, the founder of the Persian empire, issued a royal decree for the restoration of Judah and the Temple:

Thus says Cyrus king of Persia: The LORD, the God of heaven, has given me all the kingdoms of the earth, and he has charged me to build him a house at Jerusalem, which is in Judah. Whoever is among you of all his people, may his God be with him, and let him go up to Jerusalem, which is in Judah, and rebuild the house of the LORD, the God of Israel—he is the God who is in Jerusalem. (EZRA 1:2–3)

A leader of the exiles named Sheshbazzar, described in Ezra 1:8 as “the prince of Judah” (probably indicating that he was a son of the exiled Davidic king Jehoiachin), led the first group of returnees to Zion. They reportedly carried with them the Temple treasures that Nebuchadnezzar had taken from Jerusalem half a century earlier. A list of returnees by town of origin, family, and number follows, about fifty thousand altogether. They settled in their old homeland and laid the foundations for a new Temple. A few years later another wave of returnees gathered in Jerusalem. Led by Jeshua the son of Jozadak and an apparent grandson of Jehoiachin named Zerubbabel, they built an altar and celebrated the Feast of Tabernacles. In a moving scene they began to rebuild the Temple:

And all the people shouted with a great shout, when they praised the LORD, because the foundation of the house of the LORD was laid. But many of the priests and Levites and heads of fathers’ houses, old men who had seen the first house, wept with a loud voice when they saw the foundation of this house being laid, though many shouted aloud for joy; so that the people could not distinguish the sound of the joyful shout from the sound of the people’s weeping, for the people shouted with a great shout, and the sound was heard afar. (EZRA 3:11–13)

The people of Samaria—the ex-citizens of the northern kingdom and the deportees who were brought there by the Assyrians—heard about the beginning of the construction of the second Temple, came to Zerubbabel, and asked to join the work. But Jeshua the priest and Zerubbabel sent the northerners away, bluntly saying that “you have nothing to do with us in building a house to our God” (Ezra 4:3). The faction that had preserved itself in exile now believed that it had the divine right to determine the character of Judahite orthodoxy.

In resentment, “the people of the land” hindered the work, and even wrote to the Persian king, accusing the Jews of “rebuilding that rebellious and wicked city” and predicting that “if this city is rebuilt and the walls finished, they will not pay tribute, custom, or toll, and the royal revenue will be impaired . . . .you will then have no possession in the province Beyond the River.” (Ezra 4:12–16). Receiving this letter, the Persian king ordered a halt to the construction work in Jerusalem.

But Zerubbabel and Jeshua nevertheless continued the work. And when the Persian governor of the province learned about it and came to inspect the site, he demanded to know who gave the permission to start rebuilding. He was referred to the original decree of Cyrus. According to the book of Ezra, the governor then wrote to the new king, Darius, for a royal decision. Darius instructed him not only to let the work continue, but also to defray all expenses from the revenue of the state, to supply the Temple with animals for sacrifice, and to punish whoever tries to prevent the implementation of the royal edict. The construction of the Temple was then finished in the year 516 BCE. Thus began the era of Second Temple Judaism.

Another dark period of over half a century passed until Ezra the scribe, from the family of the chief priest Aaron, came to Jerusalem from Babylonia (probably in 458 BCE). “He was a scribe skilled in the law of Moses which the LORD the God of Israel had given . . . For Ezra had set his heart to study the law of the Lord” (Ezra 7:6,10). Ezra was sent to make inquiries “about Judah and Jerusalem” by Artaxerxes king of Persia, who authorized him to take with him an additional group of Jewish exiles from Babylon who wanted to go there. The Persian king provided Ezra with funds and judicial authority. Arriving in Jerusalem with the latest wave of returnees, Ezra was shocked to find out that the people of Israel, including priests and Levites, did not separate themselves from the abominations of their neighbors. They intermarried and freely mixed with the people of the land.

Ezra immediately ordered all the returnees to gather in Jerusalem:

Then all the men of Judah and Benjamin assembled at Jerusalem. . . . And all the people sat in the open square before the house of God. . . . And Ezra the priest stood up and said to them, “You have trespassed and married foreign women, and so increased the guilt of Israel. Now then make confession to the LORD the God of your fathers, and do his will; separate yourselves from the peoples of the land and from the foreign wives.” Then all the assembly answered with a loud voice, ‘It is so; we must do as you have said. . . . “Then the returned exiles did so” (EZRA 10:9–16).

Ezra—one of the most influential figures of biblical times—then disappeared from the scene.

The other hero of that time was Nehemiah, the cupbearer, or high court official, of the Persian king. Nehemiah heard about the poor state of the inhabitants of Judah and about Jerusalem’s terrible condition of disrepair. Deeply affected at this news, he asked the Persian king Artaxerxes to go to Jerusalem to rebuilt the city of his fathers. The king granted Nehemiah permission and appointed him to the post of governor. Soon after arriving in Jerusalem (around 445 BCE), Nehemiah set out on a nighttime inspection tour of the city and then summoned the people to join in a great, communal effort to rebuild the walls of Jerusalem, so that “we may no longer suffer disgrace.” But when the neighbors of Judah—the leaders of Samaria and Ammon, and the Arabs of the south—heard about Nehemiah’s plans to fortify Jerusalem, they accused the Jews of planning an uprising against the Persian authorities and plotted to attack the city. Work on the wall continued to completion nonetheless. Nehemiah was also active in implementing social legislation, condemning those who extracted interest, and urging restitution of land to the poor. At the same time, he too prohibited Jewish intermarriage with foreign wives.

These rulings by Ezra and Nehemiah in Jerusalem in the fifth century BCE laid the foundations for Second Temple Judaism in the establishment of clear boundaries between the Jewish people and their neighbors and in the strict enforcement of the Deuteronomic Law. Their efforts—and the efforts of other Judean priests and scribes which took place over the one hundred and fifty years of exile, suffering, soul-searching, and political rehabilitation—led to the birth of the Hebrew Bible in its substantially final form.

The great scriptural saga woven together during the reign of Josiah, which told the story of Israel from God’s promise to the patriarchs, through Exodus, conquest, united monarchy, the divided states—ultimately to the discovery of the book of the Law in the Jerusalem Temple—was a brilliant and passionate composition. It aimed at explaining why past events suggested future triumphs, at justifying the need for the religious reforms of Deuteronomy, and most practically, at backing the territorial ambitions of the Davidic dynasty. But at the very moment when Josiah was about to redeem Judah, he was struck down by the pharaoh. His successors backslid into idolatry and small-minded scheming. Egypt reclaimed possession of the coast, and the Babylonians soon arrived to put an end to the national existence of Judah. Where was the God who promised redemption? While most other nations of the ancient Near East would have been content to accept the verdict of history, shrug their collective shoulders, and transfer their reverence to the god of the victor, the later editors of the Deuteronomistic History went back to the drawing board.

Jehoiachin, the king exiled from Jerusalem in 597 BCE and the leader of the Judahite community in Babylon, could have represented the last best hope for the eventual restoration of the Davidic dynasty. But the previously unchallenged belief that a Davidic heir would fulfill the divine promises could no longer be taken for granted in light of the catastrophe that had just occurred. Indeed, the desperate need to reinterpret the historical events of the preceding decades led to a reworking of the original Deuteronomistic History—in order to explain how the long-awaited moment of redemption, so perfectly keyed to the reign of Jehoiachin’s grandfather Josiah, had failed to materialize.

The American biblical scholar Frank Moore Cross long ago identified what he believed to be two distinct redactions, or editions, of the Deuteronomistic History, reflecting the difference in historical awareness before and after the exile. The earlier version, which is known in biblical scholarship as Dtr1, was presumably written during the reign of Josiah and was, as we have argued, entirely devoted to furthering that monarch’s religious and political aims. According to Cross and the many scholars who have followed him, the first Deuteronomistic History, Dtr1, ended with the passages describing the great destruction of idolatrous high places throughout the country and the celebration of the first national Passover in Jerusalem. That celebration was a symbolic replay of the great Passover of Moses, a feast commemorating deliverance from slavery to freedom under YHWH and anticipating Judah’s liberation from the new yoke of Egypt under Pharaoh Necho. Indeed, the original Deuteronomistic History recounts the story of Israel from the last speech of Moses to the conquest of Canaan led by Joshua to the giving of a new Law and a renewed conquest of the Promised Land by Josiah. It was a story with an ending of divine redemption and eternal bliss.

But catastrophe struck. Centuries of efforts and hopes proved to be in vain. Judah was again enslaved by Egypt—the same Egypt from which the Israelites had been liberated. Then came the destruction of Jerusalem, and with it a terrible theological blow: the unconditional promise of YHWH to David of the eternal rule of his dynasty in Jerusalem—the basis for the Deuteronomistic faith—was broken. The death of Josiah and the destruction of Jerusalem must have thrown the authors of the Deuteronomistic History into despair. How could the sacred history be maintained in this time of darkness? What could its meaning possibly be?

With time, new explanations emerged. The aristocracy of Judah—including perhaps the very people who had composed the original Deuteronomistic History—were resettled in far-off Babylon. As the shock of displacement began to wear off, there was still a need for a history; in fact, the urgency for a history of Israel was even greater. The Judahites in exile lost everything, including everything that was dear to the Deuteronomistic ideas. They had lost their homes, their villages, their land, their ancestral tombs, their capital, their Temple, and even the political independence of their four-centuries old Davidic dynasty. A rewritten history of Israel was the best way for the exiles to reassert their identity. It could provide them with a link to the land of their forefathers, to their ruined capital, to their burned Temple, to the great history of their dynasty.

So the Deuteronomistic History had to be updated. This second version was based substantially on the first, but with two new goals in mind. First, it had briefly to tell the end of the story, from the death of Josiah to destruction and exile. Second, it had to make sense of the whole story, to explain how it was possible to reconcile God’s unconditional, eternal promise to David with the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple and the ouster of the Davidic kings. And there was an even more specific theological question: how was it possible that the great righteousness and piety of Josiah had been powerless to avert Jerusalem’s violent and bloody conquest?

Thus arose the distinctive edition known to scholars as Dtr2, whose closing verses (2 Kings 25:27–30) report the release of Jehoiachin from prison in Babylon in 560 BCE (that means, of course that 560 BCE is the earliest possible date for the composition of Dtr2). Its treatment of the death of Josiah, the reigns of the four last Davidic kings, the destruction of Jerusalem, and the exile displays almost telegraphic brevity (2 Kings 23:26–25:21). The most conspicuous changes are those that explain why Jerusalem’s destruction was inevitable, despite the great hopes invested in King Josiah. In insertions into Dtr1, a second Deuteronomistic historian added a condition to the previously unconditional promise to David (1 Kings 2:4, 8:25, 9:4–9) and inserted ominous references to the inevitability of destruction and the exile throughout the earlier text (for example, 2 Kings 20:17–18). More important, he placed the blame on Manasseh, the archenemy of the Deuteronomistic movement, who ruled between the righteous kings Hezekiah and Josiah and who came to be portrayed as the wickedest of all Judahite kings:

And the LORD said by his servants the prophets, “Because Manasseh king of Judah has committed these abominations, and has done things more wicked than all that the Amorites did, who were before him, and has made Judah also to sin with his idols; therefore thus says the LORD, the God of Israel, Behold, I am bringing upon Jerusalem and Judah such evil that the ears of every one who hears of it will tingle. And I will stretch over Jerusalem the measuring line of Samaria, and the plummet of the house of Ahab; and I will wipe Jerusalem as one wipes a dish, wiping it and turning it upside down. And I will cast off the remnant of my heritage, and give them into the hand of their enemies, and they shall become a prey and a spoil to all their enemies, because they have done what is evil in my sight and have provoked me to anger, since the day their fathers came out of Egypt, even to this day.” (2 KINGS 21:10–15)

In addition, Dtr2 presents a theological twist. Josiah’s righteousness was now described as only delaying the inevitable destruction of Jerusalem, rather than bringing about the final redemption of Israel. A chilling oracle was placed in the mouth of Huldah the prophetess, to whom Josiah dispatched some of his courtiers to inquire:

“. . . as to the king of Judah, who sent you to inquire of the LORD, thus shall you say to him, Thus says the LORD, the God of Israel: Regarding the words which you have heard, because your heart was penitent, and you humbled yourself before the LORD, when you heard how I spoke against this place, and against its inhabitants, that they should become a desolation and a curse, and you have rent your clothes and wept before me, I also have heard you, says the LORD. Therefore, behold, I will gather you to your fathers, and you shall be gathered to your grave in peace, and your eyes shall not see all the evil which I will bring upon this place.” (2 KINGS 22: 18–20)

The righteousness of a single Davidic monarch was no longer enough to secure Israel’s destiny. Josiah was pious and so was spared seeing Jerusalem’s fall. But the righteousness of all the people—given their individual rights and obligations in the book of Deuteronomy—was now the determining factor in the future of the people of Israel. Thus the rewritten Deuteronomistic History brilliantly subordinated the covenant with David to the fulfillment of the covenant between God and the people of Israel at Sinai. Israel would henceforth have a purpose and an identity, even in the absence of a king.

But even with all his twists and explanations, the second Deuteronomist could not end the story with a hopeless future. So he ended the seven-book compilation of the history of Israel with a laconic chronicle of the release of Jehoiachin from prison in Babylon:

And in the thirty-seventh year of the exile of Jehoiachin king of Judah . . . Evil-merodach king of Babylon, in the year that he began to reign, graciously freed Jehoiachin king of Judah from prison; and he spoke kindly to him, and gave him a seat above the seats of the kings who were with him in Babylon. So Jehoiachin put off his prison garments. And every day of his life he dined regularly at the king’s table; and for his allowance, a regular allowance was given him by the king, every day a portion, as long as he lived. (2 KINGS 25:27–30).

The last king from the lineage of David, from the dynasty that made the connection to the land, the capital and the Temple, was still alive. If the people of Israel adhered to YHWH, the promise to David could still be revived.

In the early days of archaeological research there was a notion that the Babylonian exile was nearly total and that much of the population of Judah was carried away. It was thought that Judah was emptied of its population and the countryside was left devastated. Many scholars accepted the biblical report that the entire aristocracy of Judah—the royal family, Temple priests, ministers, and prominent merchants—was carried away, and that the people who remained in Judah were only the poorest peasantry.

Now that we know more about Judah’s population, this historical reconstruction has proved to be mistaken. Let us first consider the numbers involved. Second Kings 24:14 gives the number of exiles in the first Babylonian campaign (in 597 BCE in the days of Jehoiachin) at ten thousand, while verse 16 in the same chapter counts eight thousand exiles. Although the account in Kings does not provide a precise number of exiles taken away from Judah at the time of the destruction of Jerusalem in 586 BCE, it does state that after the murder of Gedaliah and the massacre of the Babylonian garrison at Mizpah “all the people” fled to Egypt (2 Kings 25:26), presumably leaving the countryside of Judah virtually deserted.

A sharply different estimate of the number of exiles is ascribed to the prophet Jeremiah—who reportedly remained with Gedaliah in Mizpah until fleeing to Egypt and would therefore have been an eyewitness to the events. The book of Jeremiah 52:28–30 reports that the total of the Babylonian deportations amounted to forty-six hundred. Though this figure is also quite round, most scholars believe it to be basically plausible, because its subtotals are quite specific and are probably more precise than the rounded numbers in 2 Kings. Yet in neither Kings nor Jeremiah do we know whether the figures represent the total number of deportees or just male heads of households (a system of counting quite common in the ancient world). Given these compounded uncertainties, the most that can reasonably be said is that we are dealing with a total number of exiles ranging between a few thousand and perhaps fifteen or twenty thousand at most.

When we compare this number to the total population of Judah in the late seventh century, before the destruction of Jerusalem, we can gain an idea of the scale of the deportations. Judah’s population can be quite accurately estimated from data collected during intensive surveys and excavations at about seventy-five thousand (with Jerusalem comprising at least 20 percent of this number—fifteen thousand—with another fifteen thousand probably inhabiting its nearby agricultural hinterland). Thus even if we accept the highest possible figures for exiles (twenty thousand), it would seem that they comprised at most a quarter of the population of the Judahite state. That would mean that at least seventy five percent of the population remained on the land.

What do we know about this vast majority of the Judahites, who did not go into exile? Scattered references in prophetic texts suggest that they continued their agricultural way of life much as before. Mizpah, north of Jerusalem, was one of several towns that remained. The ruins of the Temple in Jerusalem were also frequented, and some sort of cultic activity continued to take place there (Jeremiah 41:5). And it should be noted that this community included not only poor villagers but also artisans, scribes, priests, and prophets. An important part of the prophetic work of the time, particularly the books of Haggai and Zechariah, was compiled in Judah.

Intensive excavations throughout Jerusalem have shown that the city was indeed systematically destroyed by the Babylonians. The conflagration seems to have been general. When activity on the ridge of the City of David resumed in the Persian period, the new suburbs on the western hill that had flourished since at least the time of Hezekiah were not reoccupied. A single sixth-century BCE burial cave found to the west of the city may represent a family who moved to a nearby settlement but continued to bury its dead in its ancestral tomb.

Yet there is evidence of continued occupation both to the north and to the south of Jerusalem. Some measure of self-government seems to have continued at Mizpah on the plateau of Benjamin, about eight miles to the north of Jerusalem. The soon-to-be-assassinated governor who served there, Gedaliah, was probably a high official in the Judahite administration before the destruction. There are several indications (Jeremiah 37:12–13; 38:19) that the area to the north of Jerusalem surrendered to the Babylonians without a fight, and archaeological evidence supports this hypothesis.

The most thorough research on the settlement of Judah in the Babylonian period, conducted by Oded Lipschits of Tel Aviv University, has shown that the site of Tell en-Nasbeh near modern Ramallah—identified as the location of biblical Mizpah—was not destroyed in the Babylonian campaign, and that it was indeed the most important settlement in the region in the sixth century BCE. Other sites north of Jerusalem such as Bethel and Gibeon continued to be inhabited in the same era. In the area to the south of Jerusalem, around Bethlehem, there seems to have been significant continuity from the late monarchic to the Babylonian period. Thus, to both the north and south of Jerusalem, life continued almost uninterrupted.

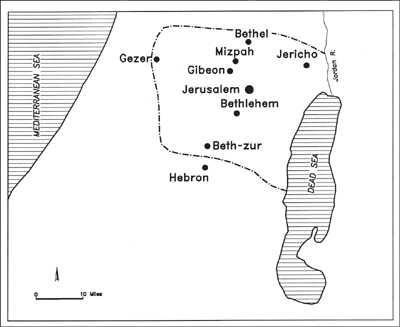

Both text and archaeology contradict the idea that between the destruction of Jerusalem in 586 BCE and the return of the exiles after the proclamation of Cyrus in 538 BCE Judah was in total ruin and uninhabited. The Persian takeover and the return of a certain number of exiles who were supported by the Persian government changed the settlement situation there. Urban life in Jerusalem began to revive and many returnees settled in the Judean hills. The lists of repatriates in Ezra 2 and Nehemiah 7 amount to almost fifty thousand people. It is unclear whether this significant number represents the cumulative figure of the successive waves of exiles who came back over more than a hundred years, or the total population of the province of Yehud, including those who remained. In either case, archaeological research has shown that this figure is wildly exaggerated. Survey data from all the settlements in Yehud in the fifth–fourth centuries BCE yields a population of approximately thirty thousand people (on the boundaries of Yehud, see Appendix G and Figure 29). This small number constituted the post-exilic community of the time of Ezra and Nehemiah so formative in shaping later Judaism.

The edict of Cyrus the Great allowing a group of Judahite exiles to return to Jerusalem could hardly have been prompted by sympathy for the people remaining in Judah or for the suffering of the exiles. Rather, it should be seen as a well-calculated policy that aimed to serve the interests of the Persian empire. The Persians tolerated and even promoted local cults as a way to ensure the loyalty of local groups to the wider empire; both Cyrus and his son Cambyses supported the building of temples and encouraged the return of displaced populations elsewhere in their vast empire. Their policy was to grant autonomy to loyal local elites.

Many scholars agree that the Persian kings encouraged the rise of a loyal elite in Yehud, because of the province’s strategic and sensitive location on the border of Egypt. This loyal elite was recruited from the Jewish exile community in Babylonia and was led by dignitaries who were closely connected to the Persian administration. They were mainly individuals of high social and economic status, families who had resisted assimilation and who were most probably close to the Deuteronomistic ideas. Though the returnees were a minority in Yehud, their religious, socioeconomic, and political status, and their concentration in and around Jerusalem, gave them power far beyond their number. They were probably also supported by the local people who were sympathetic to the Deuteronomic law code promulgated a century before. With the help of a rich collection of literature—historical compositions and prophetic works—and with the popularity of the Temple, which they controlled, the returnees were able to establish their authority over the population of the province of Yehud. What saved the day for them and made possible the future development of Judaism was the fact that (unlike the Assyrians’ policy in the northern kingdom a century before) the Babylonians had not resettled vanquished Judah with foreign deportees.

Figure 29: The province of Yehud in the Persian period.

But how is it that the Davidic dynasty suddenly disappeared from the scene? Why wasn’t the monarchy reestablished, with a figure from the royal family as a king? According to the book of Ezra, the first two figures who led the repatriates were Sheshbazzar and Zerubbabel—both are described as “governor” of Yehud (Ezra 5:14; Haggai 1:1). Sheshbazzar, the one who brought back the treasures of the old Temple and who laid the foundations of the new Temple, is an enigmatic figure. He is called “the prince of Judah” (Ezra 1:8), hence many scholars identified him with Shenazzar of 1 Chronicles 3:18, who was one of the heirs to the Davidic throne, maybe even the son of Jehoiachin. Zerubbabel, who completed the construction of the Temple in 516 BCE, also apparently came from the Davidic lineage. Yet he did not function alone, but together with the priest Jeshua. And it is significant that Zerubbabel disappears from the biblical accounts after the completion of the Temple. It is possible that his origin from the house of David stirred messianic hopes in Judah (Haggai 2:20–23), which led the Persian authorities to recall him on political grounds.

From this point onward, the Davidic family played no role in the history of Yehud. At the same time, the priesthood, which rose to a position of leadership in exile, and which also played an important role among those who had remained in Yehud, maintained its prominence because of its ability to preserve group identity. So in the following decades the people of Yehud were led by a dual system: politically, by governors who were appointed by the Persian authority and who had no connection to the Davidic royal family; religiously, by priests. Lacking the institution of kingship, the Temple now became the center of identify of the people of Yehud. This was one of the most crucial turning points in Jewish history.

One of the main functions of the priestly elite in post-exilic Jerusalem—beyond the conduct of the renewed sacrifices and purification rituals—was the continuing production of literature and scripture to bind the community together and determine its norms against the peoples all around. Scholars have long noted that the Priestly source (P) in the Pentateuch is, in the main, post-exilic—it is related to the rise of the priests to prominence in the Temple community in Jerusalem. No less important, the final redaction of the Pentateuch also dates to this period. The biblical scholar Richard Friedman went one step further and suggested that the redactor who gave the final shape to the “Law of Moses” was Ezra, who is specifically described as “the scribe of the law of the God of heaven” (Ezra 7:12).

The post-exilic writers, back in Jerusalem, needed not only to explain the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem, but also to reunite the community of Yehud around the new Temple. They needed to give the people hope for a better, more prosperous future; to address the problem of the relationship with the neighboring groups, especially in the north and south; and to deal with questions related to domestic problems in the community. In those respects the needs of the post-exilic Yehud community were similar to the necessities of the late-monarchic Judahite state. Both were small communities, inhabiting a limited territory that was only a small part of the Promised Land, but of great importance as the spiritual and political center of the Israelites.

Both were surrounded by alien, hostile neighbors. Both claimed nearby territories that were outside their realm. Both faced problems with foreigners from within and without and were concerned with the questions of the purity of the community and assimilation. Hence, many of the teachings of Judah in the late monarchic period were not alien to the ears of the people in Jerusalem in post-exilic times. The idea of the centrality of Judah and its superiority to its neighbors certainly resonated in the consciousness of the Jerusalem community in the late sixth and fifth centuries BCE. But other circumstances—such as the decline of the house of David and life under an empire—forced the early post-exilic writers to reshape the old ideas.

The Exodus story took on pointed significance in Exilic and post-exilic times. The story of the great liberation must have had a strong appeal to the exiles in Babylon. As the biblical scholar David Clines pointed out, “the bondage in Egypt is their own bondage in Babylon, and the exodus past becomes the exodus that is yet to be.” Indeed, the striking similarity of themes in the story of the Exodus from Egypt and the memories of the return from exile may have influenced the shaping of both narratives. Reading the saga of the Exodus, the returnees found a mirror of their own plight. According to Yair Hoffman, a biblical scholar from Tel Aviv University, both stories tell us how the Israelites left their land for a foreign country; how the land of Israel was considered as belonging to those who left and were expected to come back because of a divine promise; how after a difficult period in exile the people who left came back to their homeland; how on the way back the returnees had to cross a dangerous desert; how the return to the homeland evoked conflicts with the local population; how the returnees managed to settle only part of their promised homeland; and how measures were taken by the leaders of the returnees to avoid assimilation between the Israelites and the population of the land.

Likewise, the story of Abraham migrating from Mesopotamia to the promised land of Canaan, to become a great man and establish a prosperous nation there, no doubt appealed to the people of exilic and post-exilic times. The strong message about the separation of Israelites from Canaanites in the patriarchal narratives also fit the attitudes of the people of post-exilic Yehud.

Yet, from both the political and the ethnic points of view, the most severe problem of the post-exilic community lay in the south. After the destruction of Judah, Edomites settled in the southern parts of the vanquished kingdom, in the Beersheba valley and in the Hebron hills, a region that would soon be known as Idumea—the land of the Edomites. Drawing a boundary between “us” (the post-exilic community in the province of Yehud) and “them” (the Edomites in the southern hill country) was of utmost importance. Demonstrating, as in the story of Jacob and Esau, that Judah was the superior center and that Edom was secondary and uncivilized was therefore essential.

The tradition of the tombs of the patriarchs in the cave at Hebron, which belongs to the Priestly source, should also be understood on this background. The Yehud community controlled only part of the territories of the destroyed Judahite kingdom, and now the southern border of Yehud ran between the towns of Beth-zur and Hebron, the latter remaining outside its boundaries. Remembering the importance of Hebron in the time of the monarchy, the people of Yehud must have bitterly regretted the fact that in their own days it did not belong to them. A tradition placing the tombs of the patriarchs, the founders of the nation, at Hebron, would deepen their strong attachment to the southern hill country. Whether or not the story was old, and the tradition real, it was highly appealing to the authors of the Priestly source and was emphasized by them in the patriarchal narratives.

The latest editors of Genesis were not content with mere metaphors, however. They wanted to show how the origins of the people of Israel lay at the very heart of the civilized world. Thus unlike the lesser peoples that arose in undeveloped, uncultured regions around them, they hint that the great father of the people of Israel came from the cosmopolitan, famed city of Ur. Abraham’s origins in Ur are mentioned only in two isolated verses (Genesis 11:28 and 31, a P document) while his story seems much more centered on the north Syrian—Aramean—city of Haran. But even that brief mention was enough. Ur as Abraham’s birthplace would have bestowed enormous prestige as the homeland of a putative national ancestor. Not only was Ur renowned as a place of extreme antiquity and learning, it gained great prestige throughout the entire region during the period of its reestablishment as a religious center by the Babylonian, or Chaldean, king Nabonidus in the mid-sixth century BCE. Thus, the reference to Abraham’s origin in “Ur of the Chaldeans” would have offered the Jews a distinguished and ancient cultural pedigree.

In short, the post-exilic stage of the editing of the Bible recapitulated many of the key themes of the earlier seventh-century stage that we have discussed in much of this book. This was due to the similar realities and needs of the two eras. Once again the Israelites were centered in Jerusalem, amid great uncertainty, without controlling most of the land that they considered theirs by divine promise. Once again a central authority needed to unite the population. And once again they did it by brilliantly reshaping the historical core of the Bible in such a way that it was able to serve as the main source of identity and spiritual anchor for the people of Israel as they faced the many disasters, religious challenges, and political twists of fate that lay ahead.