Useful information about the global water issues in the United States and the rest of the world can often be gleaned from national, state, and local laws; court cases dealing with the topic; and statistics and data about water resources and uses. This chapter provides some of this basic information on the topic of global water issues.

Table 5.1 Quality of Various Water Resources in the United States, 2015

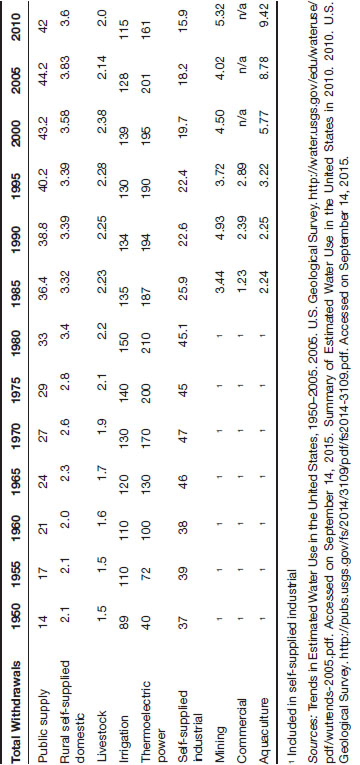

Table 5.2 Trends in Water Use in the United States, 1950–2010 (in billions of gallons per day)

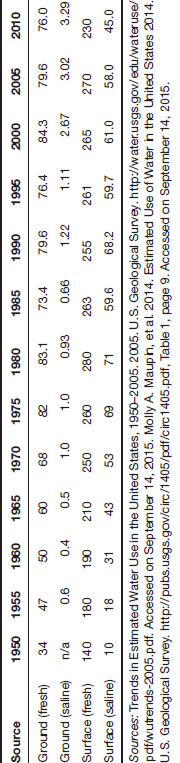

Table 5.3 Source of Water Withdrawal, United States, 1950–2010 (billions of gallons per day)

Table 5.4 Quality of Water Resources in the United States for Designated Uses, 2015

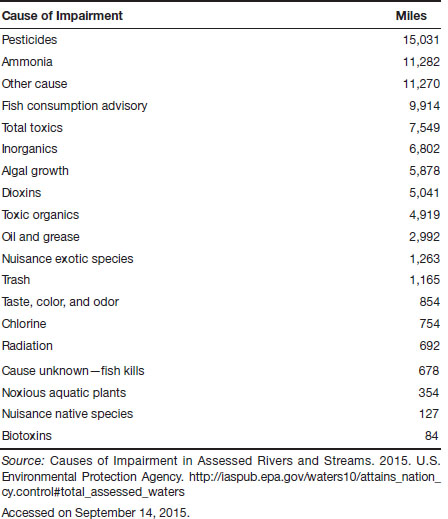

Table 5.5 Causes of Impairment in Rivers and Streams in the United States, 2015

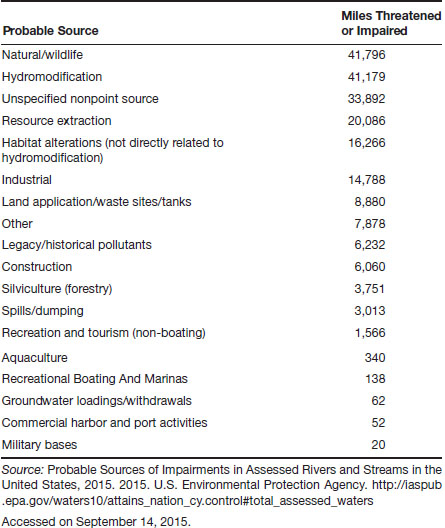

Table 5.6 Probable Sources of Impairments in Assessed Rivers and Streams in the United States, 2015

The principle of riparian rights is generally said to have its origin in the United States as a result of a case that appeared before Justice Joseph Story of the United States District Court of Rhode Island in 1827. The case arose out of a dispute between two men, Ebenezer Tyler and Abraham Wilkinson, who operated mills on the Pawtucket River as to which man, if either, had rights to use water from the river and, if permitted, to what extent. In the simplest possible terms, Justice Story ruled that each person who owned land on the river had a right to the use of a reasonable amount of water from the river. The key points of Story’s decision were later summarized in a compendium of important federal laws from the first century of the nation’s history.

Appropriation of water

Source: Peters, Richard. 1854. Full and Arranged Digest of the Decisions in Common Law, Equity, and Admiralty of the Courts of the United States from the Organization of the Government in 1789 to 1849, vol. I. New York: Lewis & Blood. The full decision in this case can be found at John Henry Wigmore. 1912. Select Cases on the Law of Torts: With Notes, and a Summary of Principles. Boston: Little, Brown, No. 245, 580–584.

The principle of riparian rights in determining control over the use of water has dominated legal thinking in the eastern part of the United States since 1827, when Tyler v. Wilkinson (provided earlier) was decided. Such has not been the case in the western part of the country, however, where doctrines other than those from English Common Law often had a strong influence. One of the earliest cases in which the question of water rights arose was Irwin v. Phillips. This case was based on a situation in which miner Matthew Irwin had settled on a piece of land in 1851, started mining for gold, and built a canal that diverted essentially all of the water from the South Fork of Poor Man’s Creek for his mining operations. A few months later, another miner, Robert Phillips, began operations in an adjacent, downstream location from Irwin’s mining site, except that no water was available for Phillips’s mining operation. Phillips sued Irwin under the riparian doctrine, arguing that anyone living and working along the banks of the river should be guaranteed access to the river’s water. The California Supreme Court disagreed with Phillips, thereby establishing the so-called prior appropriation rights document, sometimes described as the “first in time, first in right” doctrine. The court’s reasoning was as follows:

Courts are bound to take notice of the political and social condition of the country, which they judicially rule. In this State the larger part of the territory consists of mineral lands, nearly the whole of which are the property of the public. No right or intent of disposition of these lands has been shown either by the United States or the State governments, and with the exception of certain State regulations, very limited in their character, a system has been permitted to grow up by the voluntary action and assent of the population, whose free and unrestrained occupation of the mineral region has been tacitly assented to by the one government, and heartily encouraged by the expressed legislative policy of the other. If there are, as must be admitted, many things connected with this system, which are crude and undigested, and subject to fluctuation and dispute, there are still some which a universal sense of necessity and propriety have so firmly fixed as that they have come to be looked upon as having the force and effect of res judicata. Among these the most important are the rights of miners to be protected in the possession of their selected localities, and the rights of those who, by prior appropriation, have taken the waters from their natural beds, and by costly artificial works have conducted them for miles over mountains and ravines, to supply the necessities of gold diggers, and without which the most important interests of the mineral region would remain without development. So fully recognized have become these rights, that without any specific legislation conferring, or confirming them, they are alluded to and spoken of in various acts of the legislature in the same manner as if they were rights which had been vested by the most distinct expression of the will of the lawmakers… .

This simply goes to prove what is the purpose of the argument, that however much the policy of the State, as indicated by her legislation, has conferred the privilege to work the mines, it has equally conferred the right to divert the streams from their natural channels, and as these two rights stand upon an equal footing, when they conflict, they must be decided by the fact of priority upon the maxim of equity, qui prior est in tempore potior est injure (“who is first in time is first in law). The miner, who selects a piece of ground to work, must take it as he finds it, subject to prior rights, which have an equal equity, on account of an equal recognition from the sovereign power. If it is upon a stream the waters of which have not been taken from their bed, they cannot be taken to his prejudice; but if they have been already diverted, and for as high, and legitimate a purpose as the one he seeks to accomplish, he has no right to complain, no right to interfere with the prior occupation of his neighbor, and must abide the disadvantages of his own selection.

Source: Wiel, Samuel C. 1911. Water Rights in the Western States: the Law of Prior Appropriation of Water … San Francisco: BancroftWhitney, 8–10.

In 1917, the states of Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming joined together to form the League of the Southwest, an entity through which the resources of the Colorado River could be developed. Four years later, the states began a discussion of a more formal mechanism by which the water resources of the river could be distributed among the seven states. A year later, the Colorado River Compact, producing this result, was adopted by the seven states and approved by the U.S. government. The major features of that agreement were as follows.

The major purposes of this compact are to provide for the equitable division and apportionment of the use of the waters of the Colorado River System; to establish the relative importance of different beneficial uses of water, to promote interstate comity; to remove causes of present and future controversies; and to secure the expeditious agricultural and industrial development of the Colorado River Basin, the storage of its waters, and the protection of life and property from floods. To these ends the Colorado River Basin is divided into two Basins, and an apportionment of the use of part of the water of the Colorado River System is made to each of them with the provision that further equitable apportionments may be made.

***

(a) There is hereby apportioned from the Colorado River System in perpetuity to the Upper Basin and to the Lower Basin, respectively, the exclusive beneficial consumptive use of 7,500,000 acrefeet of water per annum, which shall include all water necessary for the supply of any rights which may now exist.

(b) In addition to the apportionment in paragraph (a), the Lower Basin is hereby given the right to increase its beneficial consumptive use of such waters by one million acrefeet per annum.

(c) If, as a matter of international comity, the United States of America shall hereafter recognize in the United States of Mexico any right to the use of any waters of the Colorado River System, such waters shall be supplied first from the waters which are surplus over and above the aggregate of the quantities specified in paragraphs (a) and (b); and if such surplus shall prove insufficient for this purpose, then, the burden of such deficiency shall be equally borne by the Upper Basin and the Lower Basin, and whenever necessary the States of the Upper Division shall deliver at Lee Ferry water to supply onehalf of the deficiency so recognized in addition to that provided in paragraph (d).

(d) The States of the Upper Division will not cause the flow of the river at Lee Ferry to be depleted below an aggregate of 75,000,000 acrefeet for any period of ten consecutive years reckoned in continuing progressive series beginning with the first day of October next succeeding the ratification of this compact.

(e) The States of the Upper Division shall not withhold water, and the States of the Lower Division shall not require the delivery of water, which cannot reasonably be applied to domestic and agricultural uses.

(f) Further equitable apportionment of the beneficial uses of the waters of the Colorado River System unapportioned by paragraphs (a), (b), and (c) may be made in the manner provided in paragraph (g) at any time after October first, 1963, if and when either Basin shall have reached its total beneficial consumptive use as set out in paragraphs (a) and (b).

(g) In the event of a desire for a further apportionment as provided in paragraph (f) any two signatory States, acting through their Governors, may give joint notice of such desire to the Governors of the other signatory States and to The President of the United States of America, and it shall be the duty of the Governors of the signatory States and of The President of the United States of America forthwith to appoint representatives, whose duty it shall be to divide and apportion equitably between the Upper Basin and Lower Basin the beneficial use of the unapportioned water of the Colorado River System as mentioned in paragraph (f), subject to the legislative ratification of the signatory States and the Congress of the United States of America.

Source: Colorado River Compact, 1922. U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. https://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/pao/pdfiles/crcompct.pdf. Accessed on September 11, 2015.

In 1926, the California Supreme Court heard a case, Heminghaus v. Southern California Edison, in which the owner of a large private ranch (Heminghaus) complained about plans by a large electric utility (Southern California Edison) to withdraw large quantities of water upstream of her ranch, essentially depriving her of the water needed to irrigate her fields. The court ruled in favor of Southern California Edison because the Heminghaus family held riparian rights to the river water, while the electric company held only appropriated rights. The fact that the Heminghaus use of essentially all of the river’s water to irrigate its lands seemed to be an unreasonable use of the river water, while the electric company’s use seemed to be very reasonable was thought by the court to be irrelevant to its final decision in the case. The court’s decision produced a sense of outrage among many California businesses, who saw a desperate need for more reasonable use of the state’s water resources. They formed a coalition that fought for an amendment to the state constitution requiring just such a plan when requests for use of state water resources were made. In 1928, that amendment was adopted and is now Article 10 of the state constitution. Its most important sections read as follows:

SECTION 1. The right of eminent domain is hereby declared to exist in the State to all frontages on the navigable waters of this State.

SEC. 2. It is hereby declared that because of the conditions prevailing in this State the general welfare requires that the water resources of the State be put to beneficial use to the fullest extent of which they are capable, and that the waste or unreasonable use or unreasonable method of use of water be prevented, and that the conservation of such waters is to be exercised with a view to the reasonable and beneficial use thereof in the interest of the people and for the public welfare. The right to water or to the use or flow of water in or from any natural stream or water course in this State is and shall be limited to such water as shall be reasonably required for the beneficial use to be served, and such right does not and shall not extend to the waste or unreasonable use or unreasonable method of use or unreasonable method of diversion of water. Riparian rights in a stream or water course attach to, but to no more than so much of the flow thereof as may be required or used consistently with this section, for the purposes for which such lands are, or may be made adaptable, in view of such reasonable and beneficial uses; provided, however, that nothing herein contained shall be construed as depriving any riparian owner of the reasonable use of water of the stream to which the owner’s land is riparian under reasonable methods of diversion and use, or as depriving any appropriator of water to which the appropriator is lawfully entitled.

Source: California State Constitution. Article 10. http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/.const/.article_10. Accessed on September 10, 2015. For further information on Heminghaus v. Southern California Edison, see M. Catherine Miller. 1989. “Water Rights and the Bankruptcy of Judicial Action: The Case of Herminghaus v. Southern California Edison.” Pacific Historical Review. 58(1): 83–107.

The Clean Water Act of 1972 is, technically, a set of amendments to an earlier “clean water act,” the Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1948. The purpose of the 1972 amendments was to restore and maintain the quality of the nation’s water resources by controlling the release of pollutants into rivers, streams, lakes, and other water sources. A major provision of the amendments was the creation of a permitting system, the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES), designed to control the release of pollutants from municipalities, industrial operations, and some agricultural facilities. A few of the relevant sections from the long and complex act are cited here.

“SEC. 101. (a) The objective of this Act is to restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation’s waters. In order to achieve this objective it is hereby declared that, consistent with the provisions of this Act—

“(1) it is the national goal that the discharge of pollutants into the navigable waters be eliminated by 1985;

“(2) it is the national goal that wherever attainable, an interim goal of water quality which provides for the protection and propagation of fish, shellfish, and wildlife and provides for recreation in and on the water be achieved by July 1,1983;

“(3) it is the national policy that the discharge of toxic pollutants in toxic amounts be prohibited;

“(4) it is the national policy that Federal financial assistance be provided to construct publicly owned waste treatment works;

“(5) it is the national policy that area wide waste treatment management planning processes be developed and implemented to assure adequate control of sources of pollutants in each State;

and

“(6) it is the national policy that a major research and demonstration effort be made to develop technology necessary to eliminate the discharge of pollutants into the navigable waters, waters of the contiguous zone, and the oceans.

* * *

“SEC. 402. (a)(1) Except as provided in sections 318 and 404 of this Act, the Administrator may, after opportunity for public hearing, issue a permit for the discharge of any pollutant, or combination of pollutants, notwithstanding section 301(a), upon condition that such discharge will meet either all applicable requirements under sections 301, 302, 306, 307, 308, and 403 of this Act, or prior to the taking of necessary implementing actions relating to all such requirements, such conditions as the Administrator determines are necessary to carry out the provisions of this Act.

“(2) The Administrator shall prescribe conditions for such permits to assure compliance with the requirements of paragraph (1) of this subsection, including conditions on data and information collection, reporting, and such other requirements as he deems appropriate.

“(3) The permit program of the Administrator under paragraph (1) of this subsection, and permits issued thereunder, shall be subject to the same terms, conditions, and requirements as apply to a State permit program and permits issued thereunder under subsection (b) of this section.

“(4) All permits for discharges into the navigable waters issued pursuant to section 13 of the Act of March 3,1899, shall be deemed to be permits issued under this title, …

Source: Public Law 92–500. 1972. U.S. Statutes. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-86/pdf/STATUTE-86-Pg816.pdf. Accessed on September 12, 2015.

The Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974 was passed for the purpose of protecting the nation’s freshwater supply. The act was amended twice, in 1986 and 1996, and, today, constitutes the general guidelines for ensuring the safety of the nation’s drinking water supplies. The initial 1974 act focused primarily on the treatment of water to ensure its purity and safety, while the 1986 and 1996 amendments concentrated primarily on monitoring and protecting the sources of freshwater. Relevant portions of the original act and later amendments are cited here.

“Sec. 1412 (a)(1) The Administrator shall publish proposed national interim primary drinking water regulations within 90 days after the date of enactment of this title. Within 180 days after such date of enactment, he shall promulgate such regulations with such modifications as he deems appropriate. Regulations under this paragraph may be amended from time to time.

“(2) National interim primary drinking water regulations promulgated under paragraph (1) shall protect health to the extent feasible, using technology, treatment techniques, and other means, which the Administrator determines are generally available (taking costs into consideration) on the date of enactment of this title.

[Much of this section is devoted to an explanation of the way rules and regulations for water safety are to be determined. The key provision in the section is as follows:]

“(B) Within 90 days after the date the Administrator makes the publication required by subparagraph (A), he shall by rule establish recommended maximum contaminant levels for each contaminant which, in his judgment based on the report on the study conducted pursuant to subsection (e), may have any adverse effect on the health of persons. Each such recommended maximum contaminant level shall be set at a level at which, in the Administrator’s judgment based on such report, no known or anticipated adverse effects on the health of persons occur and which allows an adequate margin of safety. In addition, he shall, on the basis of the report on the study conducted pursuant to subsection (e), list in the rules under this subparagraph any contaminant the level of which cannot be accurately enough measured in drinking water to establish a recommended maximum contaminant level and which may have any adverse effect on the health of persons. Based on information available to him, the Administrator may by rule change recommended levels established under this subparagraph or change such list.

* * *

“SEC. 1413. (a) For purposes of this title, a State has primary enforcement responsibility for public water systems during any period for which the Administrator determines (pursuant to regulations prescribed under subsection (b)) that such State—

“(1) has adopted drinking water regulations which (A) in the case of the period beginning on the date the national interim primary drinking water regulations are promulgated under section 1412 and ending on the date such regulations take effect are no less stringent than such regulations, and (B) in the case of the period after such effective date are no less stringent than the interim and revised national primary drinking water regulations in effect under such section;

“(2) has adopted and is implementing adequate procedures for the enforcement of such State regulations, including conducting such monitoring and making such inspections as the Administrator may require by regulation;

“(3) will keep such records and make such reports with respect to its activities under paragraphs (1) and (2) as the Administrator may require by regulation;

“(4) if it permits variances or exemptions, or both, from the requirements of its drinking water regulations which meet the requirements of paragraph (1), permits such variances and exemptions under conditions and in a manner which is not less stringent than the conditions under, and the manner in, which variances and exemptions may be granted under sections 1415 and 1416; and

“(5) has adopted and can implement an adequate plan for the provision of safe drinking water under emergency circumstances.

Source: Public Law 93-523. 1974. U.S. Statutes. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-88/pdf/STATUTE-88-Pg1660-2.pdf. Accessed on September 12, 2015.

[Among the many provisions of the 1996 amendments was a new focus on protecting the sources of drinking water, rather than treating water after it had left the source. The primary section dealing with this new emphasis was the following.]

“SEC. 1453. (a) SOURCE WATER ASSESSMENT.—

“(1) GUIDANCE.—Within 12 months after the date of enactment of the Safe Drinking Water Act Amendments of 1996, after notice and comment, the Administrator shall publish guidance for States exercising primary enforcement responsibility for public water systems to carry out directly or through delegation (for the protection and benefit of public water systems and for the support of monitoring flexibility) a source water assessment program within the State’s boundaries. Each State adopting modifications to monitoring requirements pursuant to section 1418(b) shall, prior to adopting such modifications, have an approved source water assessment program under this section and shall carry out the program either directly or through delegation.

“(2) PROGRAM REQUIREMENTS.—A source water assessment program under this subsection shall—

“(A) delineate the boundaries of the assessment areas in such State from which one or more public water systems in the State receive supplies of drinking water, using all reasonably available hydrogeologic information on the sources of the supply of drinking water in the State and the water flow, recharge, and discharge and any other reliable information as the State deems necessary to adequately determine such areas; and

“(B) identify for contaminants regulated under this title for which monitoring is required under this title (or any unregulated contaminants selected by the State, in its discretion, which the State, for the purposes of this subsection, has determined may present a threat to public health), to the extent practical, the origins within each delineated area of such contaminants to determine the susceptibility of the public water systems in the delineated area to such contaminants.

Source: Public Law 104–182. 1996. U.S. Statutes. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-104publ182/pdf/PLAW-104publ182.pdf. Accessed on September 12, 2015.

(For a complete review of amendments to the Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974, see Mary Tiemann. 2014. “Safe Drinking Water Act (SCWA): A Summary of the Act and Its Major Requirements.” Congressional Research Service. https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL31243.pdf. Accessed on September 12, 2015.

One of the confounding points about many water issues is that two or more legal, regulatory, or other factors may apply at the same time to a controversy. Such was the case with this dispute between an environmental organization on the one hand and the city of Los Angeles on the other. The city had obtained permits from the state as early as 1940 to draw water from five streams that feed Mono Lake in the northern part of the state, a lake of considerable natural beauty that was popular with visitors. By the time the city had actually constructed all of the diversion canals needed to withdraw water from the streams, the level of the lake had begun to drop significantly. At that point, the Audubon Society brought legal action to invalidate the city’s petition arguing that the so-called doctrine of public trust outweighed the legal right of appropriation under which the state had awarded the permits to the city. The public trust doctrine is a very ancient theory that says that certain resources are so valuable that they cannot be sold, rented, or otherwise awarded to private parties. The waters of Lake Mono, the Audubon Society argued, were protected by such a doctrine. In a long and somewhat complex decision, the California Supreme Court found for the Audubon Society, agreeing that the state had an obligation to protect the natural beauty of the Lake Mono waters. In its summary in the case, the court said that:

This has been a long and involved answer to the two questions posed by the federal district court. In summarizing our opinion, we will essay a shorter version of our response.

The federal court inquired first of the interrelationship between the public trust doctrine and the California water rights system, asking whether the “public trust doctrine in this context [is] subsumed in the California water rights system, or … [functions] independently of that system?” Our answer is “neither.” The public trust doctrine and the appropriative water rights system are parts of an integrated system of water law. The public trust doctrine serves the function in that integrated system of preserving the continuing sovereign power of the state to protect public trust uses, a power which precludes anyone from acquiring a vested right to harm the public trust, and imposes a continuing duty on the state to take such uses into account in allocating water resources.

Restating its question, the federal court asked: “[Can] the plaintiffs challenge the Department’s permits and licenses by arguing that those permits and licenses are limited by the public trust doctrine, or must the plaintiffs … [argue] that the water diversions and uses authorized thereunder are not ‘reasonable or beneficial’ as required under the California water rights system?” We reply that plaintiffs can rely on the public trust doctrine in seeking reconsideration of the allocation of the waters of the Mono Basin.

The federal court’s second question asked whether plaintiffs must exhaust an administrative remedy before filing suit. Our response is “no.” The courts and the Water Board have concurrent jurisdiction in cases of this kind. If the nature or complexity of the issues indicate that an initial determination by the board is appropriate, the courts may refer the matter to the board.

This opinion is but one step in the eventual resolution of the Mono Lake controversy. We do not dictate any particular allocation of water. Our objective is to resolve a legal conundrum in which two competing systems of thought—the public trust doctrine and the appropriative water rights system—existed independently of each other, espousing principles which seemingly suggested opposite results. We hope by integrating these two doctrines to clear away the legal barriers which have so far prevented either the Water Board or the courts from taking a new and objective look at the water resources of the Mono Basin. The human and environmental uses of Mono Lake—uses protected by the public trust doctrine—deserve to be taken into account. Such uses should not be destroyed because the state mistakenly thought itself powerless to protect them.

Source: National Audubon Society v. the Superior Court of Alpine County, 33 Cal. 3d 419; 189 Cal. Rptr. 346 [etc.]. 1983. California Courts. The Official Case Law of the State of California. http://www.lexisnexis.com/clients/CACourts/. Accessed on September 13, 2015.

One of the fundamental documents on water policy adopted by the United Nations was the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes, which was adopted in 1992 and entered into force in 1996. The document attempts to provide guidelines that countries can use in resolving disputes over water resources that are in contact with two or more discrete governmental entities. Some key provisions of the convention are the following.

1. The Parties shall take all appropriate measures to prevent, control and reduce any transboundary impact.

2. The Parties shall, in particular, take all appropriate measures:

(a) to prevent, control and reduce pollution of waters causing or likely to cause transboundary impact;

(b) to ensure that transboundary waters are used with the aim of ecologically sound and rational water management, conservation of water resources and environmental protection;

(c) to ensure that transboundary waters are used in a reasonable and equitable way, taking into particular account their transboundary character, in the case of activities which cause or are likely to cause transboundary impact;

(d) to ensure conservation and, where necessary, restoration of ecosystems.

3. Measures for the prevention, control and reduction of water pollution shall be taken, where possible, at source.

4. These measures shall not directly or indirectly result in a transfer of pollution to other parts of the environment.

5. In taking the measures referred to in paragraphs 1 and 2 of this Article, the Parties shall be guided by the following principles:

(a) the precautionary principle, by virtue of which action to avoid the potential transboundary impact of the release of hazardous substances shall not be postponed on the ground that scientific research has not fully proved a causal link between those substances, on the one hand, and the potential transboundary impact, on the other hand;

(b) the polluterpays principle, by virtue of which costs of pollution prevention, control and reduction measures shall be borne by the polluter;

(c) water resources shall be managed so that the needs of the present generation are met without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

* * *

1. To prevent, control and reduce transboundary impact, the Parties shall develop, adopt, implement and, as far as possible, render compatible relevant legal, administrative, economic, financial and technical measures, in order to ensure, inter alia, that:

(a) the emission of pollutants is prevented, controlled and reduced at source through the application of, inter alia, low and nonwaste technology.

(b) transboundary waters are protected against pollution from point sources through the prior licensing of waste water discharges by the competent national authorities, and that the authorized discharges are monitored and controlled;

(c) limits for waste water discharges stated in permits are based on the best available technology for discharges of hazardous substances;

(d) stricter requirements, even leading to prohibition in individual cases, are imposed when the quality of the receiving water or the ecosystem so requires;

(e) At least biological treatment or equivalent processes are applied to municipal waste water, where necessary in a stepbystep approach;

(f) appropriate measures are taken, such as the application of the best available technology, in order to reduce nutrient inputs from industrial and municipal sources;

(g) appropriate measures and best environmental practices are developed and implemented for the reduction of inputs of nutrients and hazardous substances from diffuse sources, especially where the main sources are from agriculture (guidelines for developing best environmental practices are given in Annex II to this Convention);

(h) environmental impact assessment and other means of assessment are applied;

(i) sustainable waterresources management, including the application of the ecosystems approach, is promoted:

(j) contingency planning is developed;

(k) additional specific measures are taken to prevent the pollution of groundwaters;

(l) the risk of accidental pollution is minimized.

Source: Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes, Helsinki, 17 March 1992. United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1936, p. 269. Reprinted by permission of the United Nations.

One of the responsibilities of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is to establish standards that will minimize the risk of serious adverse health consequences as a result of eating contaminated food products. As a step in that direction, the FDA proposes a long and detailed list of rules for ensuring food safety in 2013. Among those rules were a number that dealt with the safety and purity of agricultural water. The provisions of a key section of those rules are summarized here.

Proposed § 112.41 would establish the requirement that all agricultural water must be safe and of adequate sanitary quality for its intended use. The principle of “safe and of adequate sanitary quality for its intended use” contains elements related both to the quality of the source water used and the activity, practice, or use of the water. Uses vary significantly, including: Crop irrigation (using various direct water application methods); crop protection sprays; produce cooling water; dump tank water; water used to clean packing materials, equipment, tools and buildings; and hand washing water. The way in which water is used for different commodities and agricultural practices can determine how effectively pathogens that may be present are transmitted to produce.

. . .

Proposed § 112.42(a) would establish that at the beginning of a growing season, you must inspect the entire agricultural water system under your control (including water source, water distribution system, facilities, and equipment), to identify conditions that are reasonably likely to introduce known or reasonably foreseeable hazards into or onto covered produce or foodcontact surfaces in light of your covered produce, practices, and conditions, including consideration of the following:

(1) The nature of each agricultural water source (for example, ground water or surface water);

(2) The extent of your control over each agricultural water source;

(3) The degree of protection of each agricultural water source;

(4) Use of adjacent or nearby land; and

(5) The likelihood of introduction of known or reasonably foreseeable hazards to agricultural water by another user of agricultural water before the water reaches your covered farm.

[The proposed rules then give detailed information about each of these five conditions.]

. . .

Water treatment is an effective means of decreasing the number of waterborne outbreaks in sources of drinking water (Ref. 146). However, treatments that are inadequate or improperly applied, interrupted, or intermittent have been associated with waterborne disease outbreaks (Ref. 146). Failures in treatment systems are largely attributed to suboptimal particle removal and treatment malfunction (Ref. 147). For this reason, when treating water, it is important to monitor the treatment parameters to ensure the treatment is delivered in an efficacious manner. Monitoring treatment can be performed in lieu of microbial water quality monitoring, if under the intended conditions of the treatment, the water is rendered safe and of adequate sanitary quality for its intended use. Many operations choose to perform microbial water quality testing in addition to monitoring the water treatment as a further assurance of treatment effectiveness (Ref. 148).

Proposed § 112.43 would establish requirements related to treatment of agricultural water. [Details about the process of treating agricultural water then follow.]

. . .

Proposed § 112.44 would establish requirements related to testing of agricultural water and subsequent actions based on the test results. Specifically, proposed § 112.44(a) would require that you test the quality of agricultural water according to the requirements in § 112.45 using a quantitative, or presenceabsence method of analysis provided in subpart N to ensure there is no detectable generic E. coli in 100 ml agricultural water when it is:

(1) Used as sprout irrigation water;

(2) Applied in any manner that directly contacts covered produce during or after harvest activities (for example, water that is applied to covered produce for washing or cooling activities, and water that is applied to harvested crops to prevent dehydration before cooling), including when used to make ice that directly contacts covered produce during or after harvest activities;

(3) Used to make a treated agricultural tea;

(4) Used to contact foodcontact surfaces, or to make ice that will contact foodcontact surfaces; or

(5) Used for washing hands during and after harvest activities.

. . .

Proposed § 112.46 would establish the measures you must take for water that you use during harvest, packing, and holding activities for covered produce. Specifically, proposed § 112.46(a) would require that you manage the water as necessary, including by establishing and following waterchange schedules for recirculated water, to maintain adequate sanitary quality and minimize the potential for contamination of covered produce and foodcontact surfaces with known or reasonably foreseeable hazards (for example, hazards that may be introduced into the water from soil adhering to the covered produce)

. . .

[Section F deals with requirements for record-keeping related to all of the above rules.]

Source: Standards for Growing, Harvesting, Packing, and Holding of Produce for Human Consumption. 2013. Regulations.gov. http://www.regulations.gov/#!documentDetail;D=FDA-2011-N-0921-0001. Accessed on September 23, 2015.

One provision of the Lisbon Treaty of 2009 is that initiatives for action by the European Commission (EC) may be submitted by groups who collect at least a million signatures from at least seven member states on some topic in which they are interested. The first such petition was presented to the EC on February 17, 2014, on the subject of water and sanitation. The key element in that petition was the wish by petitioners to clarify that water is a human right, not a commodity, a dispute that has gone on in the international community for a number of years. That is, petitioners argue that access to water and adequate sanitation should not be a function of market forces, but a guaranteed right to all people of the world. Portions of the commission’s response to that petition are provided here. (Footnotes are omitted in the excerpt.)

Access to safe drinking water and sanitation is inextricably linked to the right to life and human dignity and to the need for an adequate standard of living.

Over the last decade, international law has acknowledged a right to safe drinking water and sanitation, most prominently at the United Nations (UN) level. The UN General Assembly Resolution 64/292 recognises “the right to safe and clean drinking water and sanitation as a human right that is essential for the full enjoyment of life and all human rights”. Moreover, in the final outcome document of the 2012 UN Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20), heads of State and Government and high level representatives reaffirmed their “commitments regarding the human right to safe drinking water and sanitation, to be progressively realized for [their] populations with full respect for national sovereignty”.

At the European level, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe declared “that access to water must be recognised as a fundamental human right because it is essential to life on earth and is a resource that must be shared by humankind”. The EU has also reaffirmed that “all States bear human rights obligations regarding access to safe drinking water, which must be available, physically accessible, affordable and acceptable”.

These principles have also inspired EU action. The EU Water Framework Directive recognises that “water is not a commercial product like any other but, rather, a heritage which must be protected, defended and treated as such”.

. . .

In response to the citizens’ call for action, the Commission is committed to take concrete steps and work on a number of new actions in areas that are of direct relevance to the initiative and its goals. In particular, the Commission:

Source: Communication from the Commission. 2014. European Commission. http://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regdoc/rep/1/2014/EN/1–2014–177-EN-F1–1.Pdf. Accessed on September 12, 2015.

One of the provisions of the Global Change Research Act of 1990 was that the National Science and Technology Council provide the U.S. Congress with regular reports on the status of climate change worldwide and its anticipated effects on the United States. The section of the most recent of those reports dealing with water begins with a listing of 11 “key messages” about the effects of climate change on water resources in the United States. Those key messages are as follows:

Source: Melillo, Jerry M., Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and Gary W. Yohe, eds., 2014. “Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program.”

In response to the continuing drought in the state of California, Governor Jerry Brown released the following Executive Order, designed to take aggressive action to deal with this ongoing crisis in the state. The order contains 31 sections, only some of which are summarized here.

2. The State Water Resources Control Board (Water Board) shall impose restrictions to achieve a statewide 25% reduction in potable urban water usage through February 28, 2016.

3. The Department of Water Resources (the Department) shall lead a statewide initiative, in partnership with local agencies, to collectively replace 50 million square feet of lawns and ornamental turf with drought tolerant landscapes.

5. The Water Board shall impose restrictions to require that commercial, industrial, and institutional properties, such as campuses, golf courses, and cemeteries, immediately implement water efficiency measures… .

6. The Water Board shall prohibit irrigation with potable water of ornamental turf on public street medians.

7. The Water Board shall prohibit irrigation with potable water outside of newly constructed homes and buildings that is not delivered by drip or microspray systems.

8. The Water Board shall direct urban water suppliers to develop rate structures and other pricing mechanisms, including but not limited to surcharges, fees, and penalties, to maximize water conservation consistent with statewide water restrictions.

10. The Water Board shall require frequent reporting of water diversion and use by water right holders, conduct inspections to determine whether illegal diversions or wasteful and unreasonable use of water are occurring, and bring enforcement actions against illegal diverters and those engaging in the wasteful and unreasonable use of water.

12. Agricultural water suppliers that supply water to more than 25,000 acres shall include in their required 2015 Agricultural Water Management Plans a detailed drought management plan that describes the actions and measures the supplier will take to manage water demand during drought.

25. The Energy Commission shall expedite the processing of all applications or petitions for amendments to power plant certifications issued by the Energy Commission for the purpose of securing alternate water supply necessary for continued power plant operation.

Source: Executive Order B-29-15. 2015. State of California. https://www.gov.ca.gov/docs/4.1.15_Executive_Order.pdf. Accessed on September 11, 2015.

WaterSense is a program introduced by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 2006 to promote the wise use of water in a host of consumer products and services. The program is a partnership between EPA and more than a thousand companies in a wide variety of fields including builders, governmental agencies, product manufacturers, retailers, certifying agencies, trade associations, and utilities. The program provides a label that indicates that a product or service meets certain standards for the wise use of water. The criteria on which the label issuance is based are as follows:

Some basic data and statistics on which the WaterSense program is based are as follows:

Source: WaterSense. 2015. United States Environmental Protection Agency. http://www.epa.gov/watersense/about_us/facts.html#watersense. Accessed on September 25, 2015.

Water used in the fracking of a single well ranges in the millions of gallons per well, much too high for a world that is increasingly running out of water, according to some observers. (David Grossman/Alamy Stock Photo)