THE MINUTE YOU feel fear, your first reactions will be unconscious and will take you into a primitive survival mode. Your body will react to help you to respond without thinking, releasing hormones such as adrenaline to give you immediate energy and deepening breathing and increasing your heart rate to bring more oxygen to your bloodstream, which also gives you more energy. All this is in response to one unconscious question: What do I need to do to protect myself? For some of us, that might be to fight, for others the reaction might be to flee (which is also to not fight back), and some of us might band together with others and protect ourselves as a group. When this happens, you are unlikely to feel empathy. However, if the fear can be reasoned with, thought through a bit, then the instinct will give way to cognitive processing, that is, thinking through the situation you are in. This pause for thinking gives us time to draw on what we might have previously learned about others and ourselves, and we can feel empathy.

In our modern world, feelings for survival can be triggered in different ways from our ancestors. Think of a time you might have had an emotional and illogical argument with someone. Maybe a friend made a snide comment about what you were wearing, a parent criticized you, or a co-worker made fun of you in front of others. If you can look back and analyze the situation from a third-person perspective, not from an emotionally involved place, you are likely to see that you felt attacked and were reacting instead of being thoughtful and deliberative. Your impulses to protect yourself went into gear. Unfortunately, our bodies don’t recognize the difference between an attack of words and an attack of physical danger—a threat is a threat. Once you feel threatened, the body reacts to protect itself. It takes a lot of work, including a lot of emotion regulation, to not immediately react and instead process what is going on. Maybe the friend who made the snide comment about your outfit is really insecure about how she looks and tried to make herself feel better by putting you down, maybe your father or mother wants so badly for you to be special that the criticism came from a place of wanting you to do more, and maybe the co-worker who put you down in front of others is jealous of your abilities and wants to lower you to feel higher himself. These are all common human behaviors, and there may be times when we are the one doing the “attacking” because of our own insecure or anxious feelings. Overcoming our primitive fears, which can be triggered in many different ways, is what makes being empathic so difficult. This chapter explores the many ways that fear can block empathy.

How Does the Drive to Survive Block Empathy?

We know that human beings, like other species, are wired with a strong sense of survival. Survival can be secured by our ability to read people. That ability helps us with attachment to others, to recognize danger, and to collaborate with others. These are all important survival skills. We also know that our survival at a young age depends on the care and support of other human beings. Through mirroring and affective responses, we communicate our needs and learn from others, and they in turn mirror and affectively respond and return the connection. Not only does that help us survive, but it also draws people together, which is the foundation of empathy. However, researchers have discovered that there are boundaries to this connection to others. Anything or anyone that gets in the way of our survival is a problem. When our survival is threatened by another species, such as a dangerous wild animal, we humans band together and form protection. Individual human beings could not survive for very long alone, but in groups, survival was greatly enhanced. Thus, living in groups became part of human existence over thousands of years. This is a simplistic way of describing our tribal evolution. But what happens when we perceive our survival is at risk from other human beings? Do we see those others as different from us because they threaten our survival, or do we see them as threatening our survival and therefore different from us? And within our tribe, are we sufficiently alike that we are motivated to protect and support each other, or, because we are in the same tribe, do we see ourselves as the same and it is necessary to support those like us for our own survival? The answers to these questions are key to understanding how difficult it can be to feel empathy for others who are perceived as different.

Human beings vary in different ways. We vary by sex, age, race, ethnicity, class, gender identity, religion, physical abilities, or any number of other categories into which people organize themselves. One common thread throughout the research on empathy is that if we see other people as different, it is more likely that we have a weaker empathic connection.1 And if we see others as a danger to our survival, we are even more unlikely to feel an empathic connection.

2 On a tribal level, if there is a threat to the tribe, resources and defenses are organized and the tribe fights back to restore a state of safety and survival for the tribe’s members. However, outsiders of a tribe are a social construct, a perception or belief that is created by human beings to explain or categorize other human beings. These constructs may have evolved geographically (think Southerners versus Northerners), socially (native born versus immigrants), economically (rich versus poor), or politically (Democrats versus Republicans). Some group identities are entertaining, like fans of a sports team, or are temporary, like being a student. Being a member of various groups is part of being human, so how and why do we perceive or create otherness, and how does that block empathy?

What Is “Otherness” and How Does It Block Empathy?

In research on empathy, the terms “ingroup” and “outgroup” are often used. These terms are used to describe how people divide themselves between those like us (our “ingroup” members) and those who are different from us (“outgroup” members). Decades ago, researchers documented this tendency to divide ourselves between those who we see as like us and those who we see as different.3 Even when people are divided into rather arbitrary groups, by color, for example (think the blue team versus the green team back in elementary school or summer camp), members form biases against the other team and develop favoritism for their own members.4 When group members have similarities that are longstanding, such as growing up together, being part of a religious community from birth, or living in the same neighborhood over a lifetime, bonds of similarity are strong. The stronger those bonds of similarity are, the stronger the ability for ingroup members to empathize with each other. But what happens to our empathy when we interact with people who are different?

When neuroscience began using brain imaging to look at our neural activity, scientists discovered that our empathic responses differ when we respond to people like us compared to when we respond to people who are different from us. Numerous different experiments have shown that our brain reacts similarly to the experiences of those who are like us more than it does for those who are different.5 In some cases, people do demonstrate empathy toward outgroup members but use different parts of their brains than when processing feelings for ingroup members. It seems that we mentally process members from our own group as unique individuals, while we mentally process members of outgroups as part of a whole.6 What might this tell us? It may be that we process the experiences of others, like pain, in a firsthand way for those who are like us and in a secondhand way for those who are different.7 These studies suggest that empathy can be there for outgroup members, but it may be a learned behavior using secondhand brain mechanisms for feeling what the other person is feeling compared to unconscious mirroring or firsthand experience when viewing the experiences of an ingroup member. This makes a lot of sense. We can see ourselves in others who are like us, so the unconscious and conscious parts of empathy connect smoothly and allow us to feel empathic. But when we are observing someone different, an outgroup member, we don’t experience mirroring in the same way we do for those like us. In addition, group identity can be so strong that the boundary between one’s personal self and social self (being a group member) is weak. There is a fusion of identity.8 On the one hand, this can create tremendous commitment to the group, but on the other hand it can bury individuality and self-reflection. Without self-reflection there cannot be self-other awareness, which in turn limits perspective-taking, which altogether makes feeling empathy very difficult.

Race Is a Strong “Other” in America

Race is possibly the biggest “other” we face in our nation today. Race is a difference that jumps out—we can see it right away. It has been used as a way to differentiate between “us and them” for much of American history. Today racial otherness is deeply engrained in our modern U.S. history. Slavery based on race was outlawed in this country 150 years ago, but racial segregation remained legal for another 100 years. The lived experience of legal slavery and legal segregation in the United States spanned hundreds of years, leaving a strong mental picture of otherness between races. The impact of this otherness can be seen in recent years in the reactions of whites and blacks to the police shootings of young black men and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement. The standoff between the American Indian tribal members of the Standing Rock Sioux, who were trying to protect their lands, and the builders of the Dakota Access Pipeline reflected hundreds of years of policies imposed by those in power on nondominant racial groups, thereby ignoring human rights and concerns and treating them as others.

Perception of the impact of race differs widely. According to the Pew Research Center, two-thirds of blacks say it is a lot more difficult to be black in the United States than white, while only about one-quarter of whites say the same. And 84 percent of blacks say they are treated less fairly than whites by the police, while about half of whites agree with that view.9

In case we are tempted to view this as an example of extreme fan behavior in attacking the best player on the opposing team, we must ask why the spray painting included derogatory racial terms. Would such an attack happen to a white player, and if so, would his race have been spelled out in spray paint in derogatory terms? The act of putting ourselves in the shoes of another from a social empathy perspective demands that we consider not only what it feels like to be in the other person’s situation but also what part history has played in that situation.

Michelle Alexander, in her book The New Jim Crow, a brilliant analysis of civil rights and the criminal justice system, views racial and ethnic inequality as a part of American life for a long time to come.11 Although she sees the damage of othering people by race, she also worries that if we strive for colorblindness, we will ignore all the history of differences between races that has been built into the structures of society. She argues that seeing each other’s race is not the problem; the problem is being

blind to injustice and the suffering of others…. Refusing to care for the people we see is the problem. The fact that the meaning of race may evolve over time or lose much of its significance is hardly reason to be struck blind. We should hope not for a colorblind society but instead for a world in which we can see each other fully, learn from each other, and do what we can to respond to each other with love. That was King’s dream—a society that is capable of seeing each of us, as we are, with love. That is a goal worth fighting for.12

Empathy and Race

From neural research, we know that brain activity differs when seeing the pain of those who are like us compared to those who are different, especially when race is involved.13 In one study comparing brain activity, white and black participants viewed three sets of hands being pricked with a needle.

14 The pictures included a set each of white hands, black hands, and purple hands. The researchers wanted to use the purple hands as a way to control for racial biases. They wanted to see if we affectively share pain with those like us, those different from us, and even those different in no prelearned ways, hence the purple hands. The results showed that participants did share the affective pain with all the sets of hands, but it was strongest with those who are similar (ingroup hands), weaker with those who are neutral (the purple hands), and weakest with those who are different (outgroup members). In addition, the mental sharing of pain took longer for the hands of outgroup members than it did when viewing the pictures of ingroup hands. This suggests that not only do we empathize less with people of another race, but we also process it differently in our brains.

In another study, when participants watched videos of people expressing sadness, their brain activity showed stronger sharing of the sadness with people racially like them (ingroup members) than people who differed.15 The researchers added an interesting piece to their work. They wondered if a person who was already racially biased would have even less empathic sharing with other races. As part of a psychology course, all the participants had completed a racism scale previous to the experiment. When those scores were compared to the levels of sharing in the sadness of others, the higher the score on the racism scale, the lower the shared sadness with the outgroup member. The researchers concluded that while people are less likely to feel the emotions of those who they consider outgroup members, the sharing becomes even more unlikely if that person is prejudiced.

Additional research supports the finding that there is a racial bias in empathy, but it seems to be something we are taught and is transmitted through culture.16 The fluid nature of our group identity has been seen in other experiments in which group identity is manipulated in ways that are not related to prior identities. This process involves researching human behavior when people are put in “novel groups,” such as dividing people in groups by colors or other arbitrary divisions. Novel groups have no prior socialized meaning. Yet, being placed in a novel group can even override long-standing group identities. Identifying with a group is so powerful that a new, rather innocuous identity, such as being part of the blue team in a competitive game, can connect members who may belong to other racial or social groups that, in a different setting, create “us versus them” feelings.17

Thus, although race is typically thought of as a key marker of difference among groups and has been proven to differentiate in levels of empathy for others, it seems to be rather malleable. Three group characteristics seem to be encoded in human beings as necessary to our survival: age, gender, and propensity for coalitional alliance, which is the determination of friend or foe. This makes sense based on thousands of years of human survival. What was most necessary for procreation and tribal peace was to determine who might be a suitable mate (hence the need to identify age and gender) and who could be counted on to ensure the survival of the tribe, and conversely who might be a threat to the survival of the tribe. Race as a marker of group differences is relatively new in human history. Hunter-gatherer tribes could only travel small distances and thus likely only came in contact with others who were affiliated with different tribes but looked the same. Thus, the most important factor to consider in those moments of meeting between tribes was whether they were a friend or enemy. Research has shown that assessing the likelihood of an alliance is key. Race as a categorization for group otherness is socially constructed and can be changed.18

What seems to happen is that we often encounter race as a group identity that actually covers for the friend or foe perception. We learn to associate the race of other groups as a proxy for whether they are a group that will support and work with us or that is a threat to us. It is a cognitively learned process that research has found can easily be manipulated (think of today’s political rhetoric), which is not the case for grouping by sex or age. This is good news because it means that racial bias can be unlearned, and, in turn, empathic sharing across races can be improved.

Social Stigma

In fact, this difference in how we view people with AIDS actually played out in public policy. Although AIDS as a public health concern gained attention during the mid-1980s, the federal government response was slow. In fact, the Reagan administration had quietly made it their policy to not mention AIDS to avoid dealing with it because the largest groups affected were gay men and intravenous drug users, groups for whom there was not a lot of empathy.20 Then came the story of a young boy with hemophilia living in Indiana who had contracted AIDS through a blood transfusion. Ryan White was being banned from attending school for fear of passing AIDS to other children. This brought a great deal of attention to the disease and shifted public perception in a way that made advancing policy easier—caring about a boy who, through no fault of his own, had contracted AIDS aroused much more concern than for those who had previously been identified, primarily people who were viewed with stigma: gay men and intravenous drug users. In 1990, the federal government passed the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency (CARE) Act, the first, and to this day only, federal public policy to address those who have AIDS and related health needs.

Connections Between Ingroup and Outgroup Members

Distance between groups is rather easily cultivated. Recent research has found that just the presence of an outgroup member in a group setting has the effect of dampening neural activity, making the observed person less interested and motivated in the group.21 This presents a challenge when organizing across community groups. If just the mere presence of someone seen as an outgroup member can limit neural activity, then the likelihood that empathy is blocked increases. If feeling different from others is not addressed, there will be little hope of sharing experiences and creating empathy between groups.

The research is telling us that getting to know people and finding ways to understand each other are important first steps to building empathic exchanges. Although the perceived differences between ingroup and outgroup members are powerful enough to limit empathy, it seems that when confronted with an outgroup member, if we can see individual characteristics that seem similar to us, we are more inclined to act empathically.22 What does this mean? It means that if we connect on some shared aspect when confronted by someone who seems very different or foreign to us, we can evoke empathy between us. I was indirectly taught this human ability by a story my father told while I was growing up. Although I had heard the story numerous times over my lifetime, the connection to empathy only came to me while writing this chapter.

My father was a soldier in the U.S. Army during World War II. He shared many of his experiences through his stories, spanning joining the army, training throughout the United States, transferring to Iceland and then England, landing on the beaches of Normandy, fighting through France and Belgium, being captured by the German army, spending time as a prisoner of war in Germany, and finally being liberated. As you can imagine, as much as all those experiences influenced my father, hearing stories of that journey from him influenced my growing up. One story he told strikes me as a strong example of the power of bridging the ingroup/outgroup gap through humanizing oneself to the other person, powerful enough to have saved his life.

As the end of the war was drawing near, my father and his fellow prisoners were forced to march away from the front lines, sleeping in fields at night. Food for prisoners had become even scarcer than it had already been, and starvation was a constant threat to my father’s survival. Occasionally, prisoners were assigned to local farmers to do menial tasks. One day my father was told to go help a farmer with some work on his farm. As he did so, he could smell cooking from the farmer’s kitchen and saw that a woman (likely the farmer’s wife) was making potato pancakes. She had the kitchen door open, and as my father walked by, in his broken German, he mentioned to her that his grandmother had been in Hamburg (a major city in Germany) and had also made potato pancakes. The woman looked at him and, likely from a place of connection, thinking my father had family from Germany and was missing his grandmother, gave him one of the potato pancakes she was making. When the farmer came back and found out, he was furious because helping a prisoner could have put his family in danger. For my father, he would say that potato pancake gave him nourishment that lasted for weeks, keeping him alive.

What my father’s story taught me is that his survival instinct, linked with his self-other awareness and perspective-taking, guided him to find a personal way to connect with the German woman and get her to feel his hunger. What is even more incredible about the story is that my father’s broken German was a result of having grown up Jewish and learning Yiddish, a Germanic-influenced language. Here was this Jewish prisoner of war making a personal connection with a German civilian in the midst of World War II. The story was full of other lessons. My father’s German was elementary, but he made clear to us that he said his grandmother had been in Hamburg, not that she had actually lived there. She had been in Hamburg as one of many stops along her travels as an immigrant from Eastern Europe in the late 1800s while making her way to the United States. And she did make potato pancakes. My father was very proud that in no way did he lie about any of the information he shared. I heard my father tell that story dozens of times. Only now do I realize that he was describing a way to connect with people on a personal level even when the differences were so vastly and dangerously different. It is a credit to him that he did so with full honesty, although the impression he was trying to make was clearly stronger than what may have been. What a lesson! Now, after studying empathy, I see that what my father’s intuition did to survive was in fact a well-developed social skill designed to increase empathic connection between ingroup and outgroup members. That was a skill I watched growing up. My father was a master of talking to all different types of people; for him it was a genuine interest. We used to joke that my father knew one sentence in every language because over the years, as he would meet people from different cultures, he would ask them to teach him something. As a young girl, I often felt embarrassed, like when he would ask the busy waitress who was trying to take our order how to say “how are you?” in Polish, Swedish, or Italian. But now I understand that I was watching firsthand a way to bridge otherness and connect with people from different groups, as well as how valuable that skill can be.

When Empathy Goes into Hiding: Genocide, Apartheid, and Slavery

It seems that if we can dehumanize another and completely divorce that individual from the human race, then we can sever any connection.24 That helps to explain how slavery and atrocities such as genocide can occur without empathy between the perpetrators and the victims. If the slave or the enemy is less than human, then empathic connection is blocked, and any pain or humiliation inflicted on the other is not felt. Social psychologist Peter Glick has done extensive research on the social breakdown that leads to genocide.25 He finds that when there are social, political, or economic conditions that are problematic and difficult to understand, people seek answers that make sense to them. The desire for comprehendible explanations contributes to being swayed to blame others for the problems, what he calls “ideological scapegoating.” Such stereotyping and blame can find an easy home when there are longstanding mistrust and negative beliefs about the other group. The Holocaust is a glaring example of this phenomenon. Coming out of World War I, Germany struggled economically and had trouble regaining status as a leading nation, while at the same time sharing the longstanding European undercurrent of seeing Jews as outsiders with no allegiance to their nation or values. These conditions contributed to what psychologist Ervin Staub sees as a psychological need for security, safety, and an understanding of the world.26 He argues that when these needs go unmet, stronger attachment to one’s own group feels comforting and promises solutions. The stronger the group identity, the stronger the feelings of being part of an ingroup and the stronger the difference with outgroups. Not all societies resolve complex social or economic problems with stereotyping and dehumanizing others, but we can see variations of it when certain groups are blamed for problems, such as immigrants taking jobs and thus causing economic problems or unreligious people not respecting the values of marriage in their support of same-sex unions. We’ll look at some of these growing group differences and what it might mean for our future at the end of this chapter.

Overcoming Our Group Bias

Not all social problems are viewed through ideological stereotyping. Empathy for the needs of others can be found among many groups in our nation. Empathy in spite of our needs for security, safety, and understanding can happen. Neuroscience research and analysis of history suggest that we may rely more on our hardwired biological parts to empathize with someone who is like us, a member of our ingroup, but we have to call on learned behaviors (cognitive processes) or interact with others in different ways in order to have empathy for those who are different from us.27 If this is the case, it tells us a lot about how to cultivate empathy within groups and between groups because different neural mechanisms are needed in each case. For example, when we are faced with observing those who we like and those who we do not like, there seems to be different neural activities that are called upon to process empathic feelings. In a study with Jewish male participants who were introduced via video stories to people who were designed to be likeable and people who were designed to be offensive as anti-Semitic hateful people, there were significant neural differences in how they viewed these subjects’ experience of pain (being shown each subject getting an injection in the palm of the hand).28 While the participants mirrored pain for both groups, the intensity was greater for the hateful group, and there was also greater brain activity for emotion regulation, as well as evidence of activity in the brain area that senses rewards. The participants felt the pain of both groups but may have felt a sense of satisfaction that the hateful group was getting what it deserved. That mix of emotions gave rise to the need to regulate those emotions. Hence the brain activity was different for observing the pain of likeable people versus the pain of hateful people.

Thinking in terms of the components of empathy, this means that empathy for those who are like us draws more on our affective mirroring responses so we can more easily feel and see ourselves in the other person. But empathy for people who are different may rely on the learned thinking part of our brain, on self-other awareness, micro and macro perspective-taking, emotion regulation, and contextual understanding.

Learning to Not Have Empathy

As I was doing research on how and why people commit atrocities, particularly on the Holocaust, I came across some interesting studies discussed in Roy F. Baumeister’s fascinating but dark book about evil and human violence.29 One of the atrocities committed during the Nazi rule of Germany was rounding up Jewish civilians, having them dig large pits, ordering them to undress and stand at the edge of the pit, and shooting them. If the body did not fall into the pit, the soldiers had to physically move it into the pit. As described by Baumeister in his analysis of human violence and cruelty, this would seem to be “easy” for soldiers, as it did not involve combat or threat to their own lives. However, reports of anxiety, depression, and sleep disorders were common. Those ordered to do these killings would often find ways to get out of the task, which is not surprising. But many did it and found ways to manage doing it. What seemed to be more universal, and is found in research on other perpetrators of violence such as serial killers, is that the perpetrators experienced significant physical reactions initially, including literally being sick to their stomachs. Baumeister summarizes from the research that inflicting severe harm on another person is upsetting and physically disturbing, although with repetition it becomes easier. “The distress associated with hurting or killing seems to be different from the moral or spiritual objection that might be expected. It is not that people feel that their principles have been violated, although some may indeed have such objections. Rather, it seems to be more of a gut reaction.”30

It seems that physically, emotionally, and psychologically we have a natural tendency to be opposed to killing other human beings. Lt. Col. Dave Grossman has spent years studying the act of killing in combat in order to understand how we train soldiers to overcome their resistance to killing.31 He documents a long history of soldiers in combat who found ways to avoid actually killing another human being. This aversion seems to be deeply seated in our human psyche. We recognize ourselves in the other in ways that make killing abhorrent. But people figure out ways to overcome this resistance; we have legions of examples. Foremost is physical distance: the more remote the contact, such as through long-range artillery or bombing from the air, the easier it is to kill. It is a target and not a human being. Obedience to authority can also push people to kill: “I was just following orders.” This allows for a psychological distance, not being personally responsible. Other research suggests that killing as a loyalty to your own group can be justified. If we don’t kill them, they will kill us. Perhaps most effective for close-range killing is to create emotional distance, or to portray others as less than human. Grossman summarizes this process:

When I read Baumeister’s story of German soldiers and Grossman’s analysis of the learned ability to kill, I was struck by what may happen to empathy when we are taught to kill. We know that dehumanizing others makes it easier to kill, as well as treating others as slaves and using torture and other forms of violence against them. Constructing others as not like us and less than human is a cognitive process; it can be taught. Seeing otherness can be strengthened with fear and threats to survival: “We can’t let them destroy us.” What cannot be shifted easily are our unconscious physical reactions, our mirroring or affective responses. What I see in the history of human atrocities is the social construction of dehumanizing enemies as a way of getting people to fight and kill these others. But the involuntary physical reaction of being sickened happens. Mirroring means that inflicting pain on another person will likely trigger some physical sharing of the pain. With repetition, that physical reaction gets easier to handle. Strong mental otherness imaging of others, such as calling them inhuman terms and presenting “evidence” that shows their intent to harm us, dehumanizes others so that committing violence against them becomes easier. Combine the mental image of nonhuman others with all sorts of ways that these others threaten the ingroup’s survival and we have all the ingredients needed to help perpetrators learn to tamp down the unconscious physical affective response.

There is a high cost to desensitizing people to the humanity of others. Grossman goes on to warn us that once this kind of racial, ethnic, and cultural hatred is unleashed during wartime, it can be difficult to retract for decades and even centuries afterward. He cites all the posttraumatic stress that affected soldiers on both sides of the Vietnam War as a recent example of the high personal and social cost. In chapter 5 we will explore how such stress can dampen and even cost us our empathy, creating an unfortunate, long-lasting impact of all that unleashed otherness.

However, we might be able to reverse the sense of dehumanization. In a study of real-life enemies (Jewish Israelis and Palestinians), when people were told about help that their group had given to the other group, their recognition of the outgroup’s humanity increased.33 Telling stories of help from ingroup members to outgroup members may have tapped into empathic feelings between the groups. Based on what we know about all the components of empathy, maybe a key way to address violence and enhance empathy is to stop the efforts used to dehumanize others. This includes between individuals, which might include bullying and stereotyping, and on larger social levels, in which public policies contribute to demonizing certain groups and pitting people against each other (for example, immigrants versus native born, heterosexual versus homosexual, or Muslims versus Christians). Recreating humaneness shifts the balance from “us versus them” to “we are similar and in this together.” This means that we can have empathy for all people. But it takes more work to develop empathy for those who we perceive as different from ourselves. Or, if we can shift the way we see ourselves away from ingroup and outgroup identities and instead create more global “us” identities, like being part of world humanity instead of discrete citizens of a particular country or ethnic group, then we have less of a barrier to feeling empathy for others. For me, the realization that empathic feelings are malleable reinforces the need for social empathy, taking perspective-taking deeper and broader to encompass social, economic, and cultural differences across all communities, nationally, and globally.

Empathy Is the Antidote to Otherness

While we have tremendous biological, historical, and humanly constructed ways of perceiving the danger others may pose to our safety, when we develop strong enough empathic abilities, we can change the way we see other people and other groups and then change the way we interact. Simply put, empathy is the antidote to otherness. Empathy is the solution to how we overcome prejudice, discrimination, and oppression. If empathy is the way we can overcome the otherness of prejudice, discrimination, and oppression, then it would be helpful to better understand what happens when we face those who are different from ourselves and what it means on the larger scale of communities and cultures that differ yet share our global space.

We are currently going through major social changes in the United States that increase the need for safety, security, and attachment. The potential to tap the fear from those changes is great. We hear about group differences on the news, talk radio highlights an “us versus them” mentality to create loyal listeners, and our political processes create extreme divisiveness between political parties. What we need to do is to understand those changes and then find ways to give security to those who are alarmed by them so we don’t have further growth in the distance between different groups.

Demographic Change and Why It Scares People, Triggers Survival Mode, and Blocks Empathy

The 2016 presidential election brought up many issues that were polarizing. The “us versus them” feelings were tapped in the portrayal of immigrants versus native born, race differences accentuated by police shootings of young black men giving rise to the Black Lives Matter movement, and the class difference between those at the top and those struggling to make ends meet. While watching some of Donald Trump’s campaign rallies on TV, these are some of the handmade signs I saw audience members holding up:

“Build a wall”

“Take back our country”

“Make THEM leave”

My first reaction was that this was an example of a complicated issue, immigration, reduced to ingroup versus outgroup. Using my best perspective-taking skills, I tried to understand the opposing sides on immigration in the 2016 presidential election. But promising to build a wall between the United States and Mexico was a powerful example of separating the ingroup from the outgroup. We already have portions of the wall built. I have visited the wall, and it is not a sight that makes a warm or empathic impression. It may project an image of security, but only as a physical barrier. It presents a physical divider that reinforces otherness. The wall invokes a strong message that people who are different from us should stay away. Here are some photos of the wall between San Diego, California, and Tijuana, Mexico (taken in 2013, before building it became a campaign promise). It looks like a wall around a prison. By the way, we don’t have walls like this on the border we share with Canada.

Figure 3.1 “The Wall”—The border between the United States and Mexico

Figure 3.2 “WARNING—High Security Zone—Barb Wired—Passage Is Prohibited”

We know that invoking otherness is a tactic that can bring your own group together. Typically such otherness involves demonizing the outside group. It creates an “us versus them” mentality and suggests that survival depends on sticking together and fighting off the outgroup. Calling outsiders names, like criminals or rapists, helps to separate them from the ingroup, making them less than human and consequently entirely different from us.

Donald Trump was not the first politician or leader to tap into the deeply imbedded fear of others. Part of our biological survival depended on being wary and careful about those who are different until we knew for sure whether they were safe or would harm us. We know that a sense of “otherness” exists in all of us. Wait a minute—so people screaming at each other “go back to where you came from” is biologically driven? To a certain extent, yes it is. However, the behavior to act aggressively or violently based on otherness, although possibly triggered by fear of others, is more likely a learned reaction, particularly in our modern world. Chances are that most of the people who worry about harm that will come to them from people who look different from them actually have no real personal experience with those who are different and whom they fear. It is a learned response that comes from a place of fear, fear that your comfortable survival zone is at risk. What triggers this fear? Change that feels like a disruption to your equilibrium, what you know to be right, and your safety. Although the United States has been shifting demographically for hundreds of years, the fears of otherness today are based on changes that have been rather significant over the past fifty years. Some of the demographic and social changes that have upended the status quo have come quickly, over the past ten to twenty years.

The United States Is Changing Very Fast

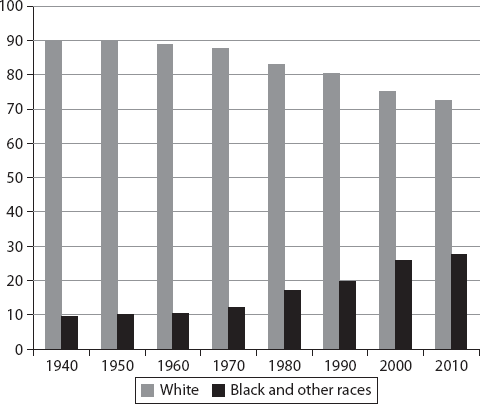

Until the 1980s, the proportion of the population that was identified as white was a large majority, almost 90 percent. From 1980 to 2010, according to the official census (which many argue undercounts members of nondominant groups because they can be harder to locate due to more frequent moves and are less likely to respond due to mistrust of authorities), the proportion of the white population in the Unites States declined by almost 13 percent, while those identified as black, mixed race, or other grew by more than 60 percent (see table 3.1 and figure 3.3). The Latino population, which can be white or black, also grew by more than 150 percent. Looking at 2010, we can see that the population of the United States was more than one-quarter people of color. Based on the changes of the past fifty years, the Census Bureau estimates that by 2060 one-third of the population will be people of color and almost 30 percent will be Hispanic.

Population Distribution from 1940 to 2010 According to the U.S. Census Bureau

| |

White (%) |

Black (%) |

Other/Mixed races (%) |

Hispanic or Latino (%) |

| 1940 |

89.8 |

9.8 |

|

|

| 1950 |

89.5 |

10.0 |

|

|

| 1960 |

88.6 |

10.5 |

|

|

| 1970 |

87.5 |

11.1 |

1.4 |

4.5 |

| 1980 |

83.0 |

11.7 |

5.3 |

6.4 |

| 1990 |

80.3 |

12.1 |

7.6 |

9.0 |

| 2000 |

75.1 |

12.3 |

12.6 |

12.5 |

| 2010 |

72.4 |

12.6 |

15.0 |

16.3 |

Figure 3.3 Changes in U.S. population, 1940–2010

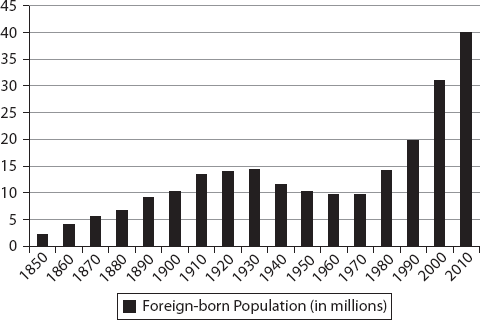

Net Immigration

| 1931–1940 |

121,000 |

| 1941–1950 |

754,000 |

| 1951–1960 |

2,090,000 |

| 1961–1970 |

2,422,000 |

| 1971–1980 |

3,223,000 |

| 1981–1990 |

5,655,000 |

| 1991–2000 |

6,743,000 |

| 2001–2010 |

7,396,000 |

Figure 3.4 Foreign-born population (in millions)

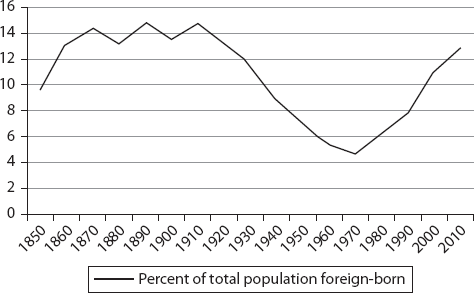

Figure 3.5 Percent of total population foreign born

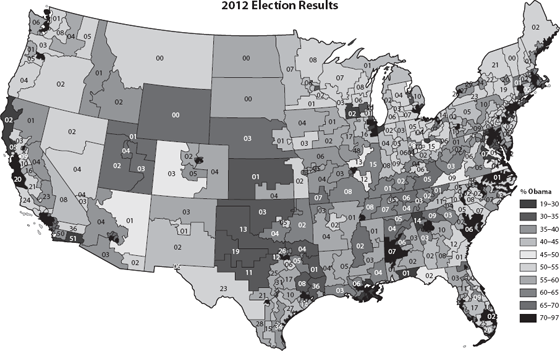

We have also seen shifts in our values, as more than 60 percent of all Americans support same-sex marriage.36 These demographic and social value changes, while overall representing significant proportions of the population, are not evenly distributed geographically. Much of the demographic changes have taken place in urban areas, and the acceptance of value shifts, such as support of same-sex marriage, is also geographically split and divided by political party.

37 Consider the political divide among the states most supportive of same-sex marriage (Washington, Oregon, Colorado, Vermont, New Hampshire, New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Jersey, and Delaware) and the states least supportive (Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, Arkansas, South Dakota, Louisiana, Utah, and North Dakota). All the high-support states voted for the Democratic candidate, Barack Obama, in the 2012 presidential election, and all the least supportive states voted for the Republican candidate, Mitt Romney.

38

Another area of demographic change that has likely contributed to unease with how the country has shifted in recent years is the place of women. In 1950, one-third of women participated in the civilian labor force compared to almost 90 percent of men. By 2010, the rate for women had almost doubled to 60 percent of women actively engaged in the civilian labor force, while the rate for men had actually dropped to just over 70 percent. Overall, from 1950 to 2010, the rate for men dropped almost 18 percent over the sixty years and increased for women by almost 73 percent.39 A shift in religious identification has been coupled with all these demographic and value changes. According to Gallup polls taken over the years, those who identify as Christian has declined from 91 percent in 1950 to 72 percent in 2015.40

Perhaps the most telling statistic about these changes comes from another Pew Research national survey.41 In response to the question “Compared with fifty years ago, life for people like you in America today is better, worse, or the same?” 81 percent of Trump supporters said it was worse compared to only 19 percent of Clinton supporters, and only 11 percent of Trump supporters said it was better compared to 59 percent of Clinton supporters. The way our country has changed over the past fifty years has split us between those who feel those changes are for the better and those who feel they are for the worse. These numbers show that fear of how our country has changed became linked to a political candidate.

What do all these changes mean? For those who are not accustomed to living, working, and socializing with other racial, ethnic, religious, or sexual identity groups, it means the safety of their ingroup dominance is being challenged. Members of dominant groups are not used to being challenged in this way. Being on the outside as a minority typically means one has to be able to cross social and economic divides. Belonging to a nondominant group tends to make one more empathic compared to those who are part of the dominant culture because one has to understand both one’s own culture and that of the majority.42 The ability to emotionally and cognitively understand both one’s own culture and those that are different from your own is often referred to as “intercultural” or “ethnocultural empathy.” For example, if you grow up poor in a community of color and want to go to college, you will likely have to learn how to navigate the world of the dominant culture. I learned this lesson from one of my first students. It was my very first time teaching. I was a graduate student teaching an introductory course. Like most first-time teachers, I was very nervous and wanted to do well. I had some diverse students; in fact, what I loved about the university was that I found it very diverse, especially compared to the small liberal arts college I had attended as an undergraduate. It was a public university on an urban campus with thousands of students, with people from different racial and ethnic backgrounds. After I handed back an assignment, I noticed a young African American women who sat in the back. She did not speak in class, and I was worried about her body language. At times she looked bored and at times she looked annoyed. I was not sure how to reach her, and I was especially nervous about it because of my very limited experience teaching. I was thinking about asking my advisor for some direction.

That week I was on my regular subway commute to school, and at the transfer stop, who do I see but my student. I said hello and asked her how things were going. She shrugged and said something about not understanding my class. I jumped on the chance and suggested she come to my office, where we could talk about what was not clear. Thankfully she took me up on the offer. We started reviewing the course material, and she told me about her journey to the university. She had been a straight-A student at an all-black local community college. She was the only person in her family to go to college. She had just transferred to the university, and this was her first quarter. Over the course of numerous meetings, I learned a lot from her. For her, our university was the whitest institution she had ever been a part of, and she was uncomfortable. All her professors were white, unlike at the community college. She was uncomfortable approaching them, and they did not approach her. It was eye opening for me because I thought we had such a diverse university. She had never seen such a large library and did not know how to use it. All her instructors at the community college let their students hand-write their papers; here she was supposed to type her work. She did not have a typewriter. (This was years before personal computers.)

I was struck by how different life for her was at this urban, public university from what I imagined it to be. It was a humbling experience. We went to the library together, where she learned how to do research for my class; she did very well. She was a very smart young woman. I wish there had been a happy ending. She stopped by periodically after our class ended and gave me updates. She had not connected with any other professors (unfortunately I was only a graduate student, not a professor) and found their courses to be difficult. Biology was the worst; she had never been in a laboratory before. She came by less and less, and when weeks had gone by with no word, I asked our registrar about her. I was told she was on leave. She never came back. She had started to learn the process of operating within a culture that was new and foreign to her, but it was too much. The university had no system of support for students like her. I learned a lot from her experience, and it helped me to understand the huge divide between the dominant and nondominant culture and the cost of being an outsider in my university world. I could not do much on an individual basis, so I was drawn to figure out what should be done on a societal basis. This was one more experience that led me to social empathy.

Can We Bridge the Otherness Divide?

As I was writing this chapter, I was struck by how different urban and rural life in the United States is when it comes to interactions among people who are different in the ways that ask us to demonstrate intercultural empathy, such as with people of other races, ethnicities, and classes. In most urban areas, even when people do live divided by race, ethnicity, and class, there are more interrelations and thus people are more likely to mix in what I call “micro novel groups.” Remember that novel groups are those groupings that are arbitrary and not based on shared meaningful differences. In spite of the superficiality of a novel group, membership can override biases based on previous ingroup and outgroup identities. Thus, being divided into the purple team versus the yellow team to play a game or work on a project can create a unified identity that overrides that of each person’s individual race, ethnicity, or class identity. Could it be that living in a community in which you move in and out of micro novel groups with mixed identities creates more tolerance and understanding of people who are different? I am thinking of the years when I commuted to work on public transportation in very multicultural cities. Sometimes something quirky would happen, such as a sudden stop or the driver making an announcement that no one could understand. People would have brief moments of unification, asking each other what was going on or sharing surprise at the suddenness of the stop. This moment creates a micro novel group: the riders on that subway train. Living in diverse urban areas means it is more likely that one will work in places with diverse colleagues and interact with people from different backgrounds for day-to-day living tasks such as grocery shopping, moving through multiple micro novel groups.

Figure 3.6 2012 general election results

The urban-rural divide was evident again in 2016. Of the twenty-five most populous cities in the United States, twenty-two went to the Democratic candidate in the 2016 presidential election. Of those twenty-two cities, more than half (twelve) were in Republican majority states. That includes cities like Houston, Indianapolis, Memphis, Charlotte, Dallas, and Nashville, all in solidly red states.

What does this tell us? First, that urban areas vote differently than nonurban areas. Second, that diversity is more prevalent in urban areas, while homogeneity is more prevalent in rural areas. These geographic areas reflect different experiences, values, and beliefs. These differences make empathic understanding between groups challenging. If we want to promote empathy across different groups, we need to find ways to override ingroup bias. Research tells us that can be done through cognitive training: the rethinking of our patterns of ingroup dominance. Having experiences with members of different groups is one way to help us develop the neural pathways that shift views of otherness and group differences. The challenge is finding ways to connect different groups in meaningful ways across geographic and cultural distances.

I had finished the first full draft of this book a few days before white supremacists marched in Charlottesville, Virginia, on the campus of the University of Virginia in August 2017.47 I watched the television on Friday night as the news showed live images of hundreds of all-white marchers, most of them young men, carrying flaming torches and yelling Nazi slogans. All I could think about were two sets of images I had seen in black-and-white grainy film: of Kristallnacht,

48 the night in 1938 when Nazis across Germany and Austria looted and destroyed Jewish shops and synagogues using torches to ignite fires, and of hooded KKK members over many decades riding on horses at night holding burning torches, circling the homes of African American families while dragging a family member out to be lynched. I knew those images were exactly what those marchers wanted me to see—at least those who planned it. There were hundreds of torches; this was a well-orchestrated message. It’s very possible that many of the marchers did not know the historical facts of Kristallnacht or the depth of the legacy of lynching, but they knew that carrying those torches would scare those who were the targets of their hatred.

The visceral fear that I and so many other people felt that night and the next day was intentional; it was a blatant example of using otherness to intimidate and control those who are different. It showed reading other people, but it lacked walking in their shoes. Those marchers did not imagine themselves or their loved ones in the place of those being terrorized, and they did not show that they considered the targets of their hatred to be human beings like themselves. Am I being too harsh or overgeneralizing? There probably were some who marched without fully understanding the implications of what they were doing, but their ability to take the actions they did shows that they saw people different from them as others, people to whom they could not relate or feel similar. And how do we know that? By the slogans they chanted, the symbols they carried, the goals they espoused, and, ultimately, by purposefully taking the life of someone who came out that day to stand against their show of hatred.