1

THE REBORN WRATH OF PELEUS’ SON

Would Alexander have been content to die without making a Will and without planning for a succession?

Historians have been trying to unveil the man behind the legend for the past two millennia, and the opinion of every age has, to some degree, reshaped Alexander III of Macedonia.

What did it mean to be descended from the Macedonian royal house with an elite Greek education? What was Alexander’s relationship with his father, his men, their high-ranking generals, and with his entourage of court ‘friends’, diviners, philosophers and poets? And what part did Homer, Herodotus, Xenophon, and Aristotle’s view of the barbarian Persian Empire play in his character development?

We look at Alexander’s policy, his behaviour and mindset on campaign to question whether this correlates with the man who allegedly declined to recognise his sons as heirs and failed to provide succession instructions to his generals.

‘My vast army marched into Babylon in peace; I did not permit anyone to frighten the people of Sumer and Akkad. I sought the welfare of the city of Babylon and all its sacred centres. As for the citizens of Babylon, upon whom he [Nabonidus] imposed a corvée, which was not the god’s wish and not befitting them, I relieved their weariness and freed them from service. Marduk, the great Lord, rejoiced over my deeds.’1

The Cyrus Cylinder

‘A man, he shunned humanity; it seemed A trifle to stand highest among mortals.’2

Gautier de Chatillon Alexandreis

‘… the gods and heroes begrudge that a single man in his godless pride should be king of Hellas and Asia, too.’3

Themistocles, Herodotus Histories

Babylon, mid-June 323 BCE, the ‘gateway of the gods’; an ancient city already two millennia old and which, according to legend, was founded by the Mesopotamian deity, Marduk.4 This was now the Macedonian campaign capital and the staging point for the planned expeditions to Arabia and westward to the Pillars of Heracles. Inside the lofty baked-brick and bitumen-bound walls, the city had become a hive of activity with trepidatious envoys arriving from nations across the known world, those conquered and those expecting to be.5 Prostrated in the Summer Palace of Nebuchadnezzar II on the east bank of the Euphrates, wracked by fever and having barely survived another night, King Alexander III, the ruler of Macedonia for twelve years and seven months, had his senior officers congregate at his bedside.6 Abandoned by Tyche who governed fortune, and the healing god Asclepius, he finally acknowledged he was dying.7

Growing fear and uncertainty filled the portent-laden air. Priests interpreted omens, livers and entrails as whispered intrigues and newly divulged ambitions filled heavy sweat-soaked nights. Life signs were tenuous; the king’s breathing was almost imperceptible. Finally, Alexander, born under the watch of two eagles that signified two great empires, and birthed from a womb sealed with the image of a lion,8 was publicly pronounced dead and the prophecy of the Chaldean seers came to pass.9

The ancient city founded over 1,000 years before the legendary fall of Troy was a fitting stage for the death of the king who had conquered the empire of the Persian Great Kings and vanquished their progeny, for Alexander had married daughters of both Darius III (king 336-330 BCE) and Artaxerxes III Ochus (king 359/358-338 BCE). The backdrop was no mud-brick town in the eastern regions the Greeks loosely termed ‘India’, or windswept pass in the upper satrapy of Bactria, or, as the Greek historian Plutarch put it, ‘that nameless village in a foreign land must needs have become the tomb of Alexander’, but the greatest opulence the world had to offer.10 It was appropriately theatrical and it was uniquely ‘Alexander’ and yet the reporting is wholly unconvincing as a conclusion to his story. Alexander’s final days should have provided us with the rich and colourful imagery we read in the campaign accounts, for by mid-summer 323 BCE, warships, grain ships, pack animals, cavalry mounts and Indian elephants were being prepared for a new Arabian expedition, while the citadel guarding wealth the Greeks had never imagined was being mined for funds to pay what had become a multinational army.

Gossiping eunuchs, concubines and wives frequented the Summer Palace of Nebuchadnezzar II (Naboukhodonosor to the Greeks, reigned ca. 605-562 BCE). Bodyguards, physicians, slaves, scribes, cooks, tasters and royal pages filed through anterooms filled with waiting ambassadors who brought dispatches from distant lands at the borders of the known world. According to Plutarch, the palace was now full of ‘soothsayers (magoi), seers (manteis), sacrificers, purifiers (kathartai) and prognosticators’; by-products of the king’s late obsession with death-harbouring portents.11 As events had already shown on more than one occasion, it was the seers and doctors, fearful of providing inaccurate divinations or ineffective prognoses, who had the most to lose: their lives.12 So no doubt spells (epoidai) and incantations (epagogai) had been covertly cast as complex fears and political intrigues manifested themselves in dark corridors as Alexander’s health continued to deteriorate. Indeed, the surviving texts ought to have replicated the drama captured in the final chapter of the Cyropaedia of Xenophon (ca. 430-354 BCE), the vivid and laudatory portrayal of the former Persian Great King.13

Cyrus the Great (reigned 559-530 BCE) becomes significant to our case, for Alexander inherited the Achaemenid Empire he had founded and he appears to have become an admirer. The Cyropaedia, which can be broadly translated as ‘the education of Cyrus’, laid out the perfect death for a king of kings.14 Surrounded by the loved and faithful, Cyrus distributed his kingdom to his two sons, making sure no ambiguity or conflict would arise. According to Xenophon, both he and Darius I left enduring traditions that included oral testaments and farewell speeches of enlightened and benevolent words. They rounded off careers that had already become immortal, and Cyrus’ ended his with: ‘Now I must leave instructions about my kingdom, that there may be no dispute among you after my death.’15 Although Cyrus’ final hours were, in fact, the encomiastic overlay of a Greek historian, Alexander had about him all that was required to do the same, along with a prolonged illness that provided sufficient time. According to the surviving mainstream accounts, he failed in every respect, even when, as one tradition claims, he was being pressed by his generals to announce a successor. We are left wondering what truly took place at Babylon, and who Alexander had become, for it is not only accounts of his death that conflict, but opinions of his life.

According to Aristotle, Zoroastrianism and the Magi of the East believed there are two ‘first principles’ in the world: ‘A good spirit and an evil essence; the name of the first is Zeus or Ahura Mazda, and the other Hades or Ahriman.’ This dualism could have featured in any introduction to the life of Alexander so divergent is his character portrayal within the Vulgate genre.16 Written in vastly different times, two books became required reading for the American founding fathers as a lesson and warning on the nature of governance: Machiavelli’s The Prince and Xenophon’s On the Education of Cyrus, copies of which remain today in the US Congress Library. Like the Magi’s opposed spirits, they represent the two faces of man: one promoting rule by fear and the other by benign enlightenment, and each book had its place in the evolving profile of the Macedonian king.

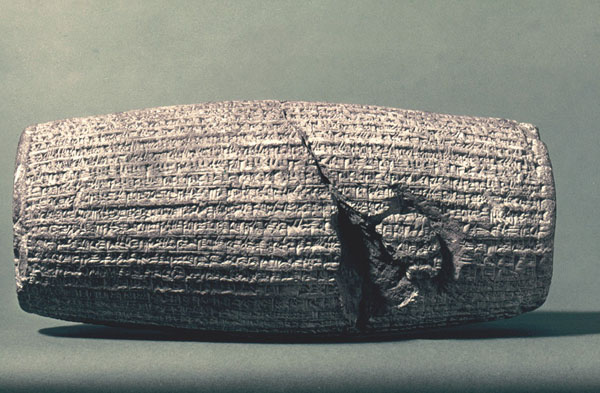

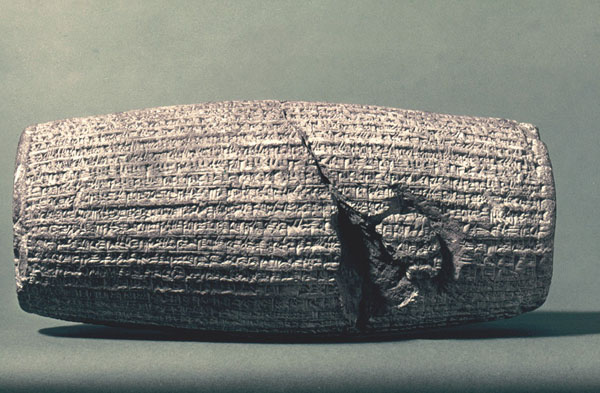

One of the leitmotifs of Alexander’s story is his belief in his own divine and heroic origins. Yet he also had mortals to emulate and one of them was Cyrus the Great. Two centuries before him – tradition suggests October 29th 539 BCE – Cyrus stood on the steps of the ziggurat of Etemenanki, the ‘Cornerstone of the Universe’, and dedicated to the god Marduk in his newly conquered Babylon.17 Rejecting the slavery and loot which was his by Victor’s Justice, he purportedly made an address which is widely regarded as the first charter of human rights. In 1879 a clay cylinder was unearthed at Babylon and it recorded the complete address previously known to us only from the biblical references in the Book of Ezra, chapter one. A copy of the so-called Cyrus Cylinder now sits in the halls of the United Nations Secretariat Building in New York.18

Portrayed as politically astute, in the first years of the campaign at least, Alexander III chose to emulate Cyrus when in 333 BCE he too entered Babylon for the first time via the ancient Processional Way having just defeated Darius III. He respected personal freedoms as well as local religious rights, and surviving cuneiform inscriptions found in the city’s astronomical diaries captured a part of the declaration: ‘Into your houses I shall not enter.’19 Alexander even sought to repair the Esagila Temple whose golden statue had been melted down by Xerxes upon his hasty return from Greece following defeat at Plataea in 479 BCE, a battle whose aftermath saw Greeks conducting annual sacrifices to their dead in Plutarch’s day, some 600 years on.20 This, along with the adoption of Persian customs and his inheriting a still largely unified Persian Empire, had led some modern commentators to even refer to Alexander as ‘the last of the Achaemenids’.21

The 22.5 cm clay Cyrus Cylinder, inscribed with Akkadian cuneiform, tells of Cyrus’ conquest of Babylon in 539 BCE and the capture of King Nabonidus. The account details Cyrus’ benevolence and tolerance, which followed a long tradition of Mesopotamian victory declarations. Discovered in 1879, it resides in the British Museum.

THE THEOGONIA OF THE ELUSIVE COMPARANDUM

Whether Alexander displayed a genuine Graeco-Oriental spirit unique for his time, or simple political expediency, is perennially debated, but few men in history have been subjected to so many post-mortems through the ages; his body of literature was bruised by, or benefited from, the ebbs and flows of the philosophical movements and social tides that washed back and forth across the ‘universal Comparandum’, as Alexander has been termed.22

In his Prior Analytics Aristotle proposed that it is possible to deduce a person’s character from their physical appearance, though the contradictions found in the descriptions of Alexander render any conclusion suitably ambiguous.23 We are told that though he was of average height, he was striking and menacing even, with a melting glance of the eyes. His breath and skin, according to the Memoirs of Aristoxenus of Tarentum (a pupil of Aristotle), exuded a sweet odour, but they were the by-products of his hot and fiery temperament, so his contemporary, Theophrastus (ca. 378-320 BCE), believed. His voice was described as harsh yet also femininely high-pitched; he sported a gold leonine-mane with anastole in the heroic style, but he chose to remain beardless; this became a new vogue for him and his men.24 Alexander appears to have been heterochromatic, with one pupil black and the other grey, and his widely reported neck tilt suggests torticollis (wry neck). His teeth were asserted to be sharp and pointed like those of a snake, but this comes from the Greek Alexander Romance with its many serpent associations.

Clearly, many of the descriptions, like other detail relating to his life, come down to us from the Roman era and from anonymous, dubious and romanticised sources with little court authentication.25 Yet it is not Alexander’s physiognomy but his character and mindset that remain the more elusive, despite the best attempts of Quellenforschung to unmask the man behind the rhetorical veil. Modern historians soon discovered they lacked the vocabulary to cope with him, and word hybrids like verschmelzungspolitik appeared to describe what some have romantically believed was his ‘policy of racial fusion’.26 So perhaps we should try and appreciate how Alexander III originally viewed himself in the light of his unique and privileged, though hazardous, Macedonian heritage and upbringing.

Some modern scholars accept that the origins of the ethnic, Makedones, approximated ‘men from the highlands’ or even ‘high-grown men’, though the ancient authors that shepherded Greece out of the Dark Ages proposed a more colourful, though conflicting, genesis.27 Hesiod’s Theogonia (likely 7th century BCE) and the Catalogue of Women, a supposed continuation that was attributed to him in antiquity, were cosmogonies that provided the archetype of mythical genealogical claims, though they made little of nationalist distinctions and some of this early material was even influenced by the religious doctrine of Babylonia and Mesopotamia, including the Epic of Gilgamesh.

In Hesiod’s legends (and those attached to him) the origins of tribal Greece and Macedonia started with Deucalion who bore a son, Hellen, from whom the ‘Hellenes’ were derived. He in turn bore three sons who became the founders of eponymous tribes: Aeolus, Dorus, and Xuthus who bore Ion and (according to other writers) Achaeus. By Zeus, Deucalion’s daughter, Thyla, produced two sons, Magnes, and Macedon who ‘rejoiced in horses’; Magnes journeyed south into Thessaly and Macedon remained in the region of Mount Olympus and Pieria, the heartland of what was once Emathia, the ‘prehistoric name for the cradle of the Macedonian kingdom’. A fragment of the Makedonika of Marsyas of Pella (broadly contemporary with Alexander) informs us that it was the two sons of Macedon, Amathus and Pieria, who became the eponymous founders of these two regions.28

But whether Alexander considered himself ‘Macedonian’ in the tribal sense of the word is open to question; he was in any case half-Epirote through his mother, and he likely embraced a more Aristotelian definition of identity approaching ‘to Hellenikon’. To Herodotus (ca. 484-425 BCE) the ‘Hellenes’ were a people bound together by blood, speech, religion and a common mode of living. Of course if your tribe was lucky enough to appear on Homer’s Catalogue of Ships which listed the assailant fleet to Troy, then your ‘Greekness’ – or allegiance to Hellas at least – was beyond question, though the Iliad appears to have portrayed the Trojans as Greek-speaking as well.29

In the Homeric epics, the ethnonyms and endonyms of early tribal appellations were not always easy to follow; the ‘long-haired Achaeans’ (Akhaiwoi in ancient Greek, Akaiwasha to the Hittites) that followed Achilles to war are at times ethnically distinct, and in other cases they represented the total ethne of mainland Greece.30 The Catalogue of Ships itself presented the diversity of the invading ‘Achaean’ army heading to Asian shores; Homer declared (sometime in the 9th century BCE, debatably): ‘For I could not count or name the multitude who came to Troy, though I had ten tongues and a tireless voice, and lungs of bronze as well.’31 In the Illiad and Odyssey, the Danaoi (or Danaans, possibly the Danuna mentioned in Hittite and Egyptian records) and ‘Argives’ were repeatedly cited in some collective tribal fashion representing the invading Greeks led by Agamemnon.32

As with all else he touched, Alexander’s teacher, Aristotle, attempted to bring some rationalisation to the ‘pre-history’ of Greece after the fall of Mycenaean civilisation; he described ‘ancient Hellas’ as being occupied by Selloi (Zeus’ priests, likely an alternative of Helloi) and Graikoi, who later became known as the homogenised to koinon ton Hellenon, which we might loosely term a ‘Hellenic commonwealth’.33 The Periegetes Hellados of Pausanias (ca. 110-180 CE), his unique Guide to Greece (though a Greece whose northern boundary was the pass at Thermopylae) in the form of a straight-talking guide interwoven with the history, architecture and ancient Greek myths, mentioned that an inscription by Echembrotus dating to the 48th Olympiad (584 BCE) employed the term ‘Hellenes’ in a dedication to Heracles at the Amphictionic Games.34 A similar dedication at Delphi celebrating victory over Persia credited another Pausanias as the leading general of this ethnic group; it was a unity further endorsed at the fourth Panhellenic Games in which ‘non-Hellenes’ could not participate in any of the disciplines.

Plato (ca. 428-348 BCE) believed the most ‘Greek of the Greeks’ were the Athenians, and in the dialogue of the Menexenus (attributed to him), Aspasia, the mistress of the Athenian statesman Pericles, (ca. 495-429 BCE) proposed only Athenians were pure and free from barbarian blood.35 According to Herodotus, Athenians (and other pre ‘pre-Hellenised’ tribes) were once Pelasgians, arriving through migration, or the autochthonic inhabitants.36

Clearly, there had been no original Pan-Hellenic name for what became the Greek homeland, populated as it was with at least two major tribal migrations, the first by the Ionians and Aeolians (perhaps 16th century BCE, if so, this coincided with the emergence of what we now term the Mycenaean civilisation) and later the Dorians (11th century BCE), though from exactly where (and why) they came is unknown.37 These racial exoduses took place in mytho-historical eras between which the mysterious ‘Peoples of the Sea’ (perhaps including Greek tribes) caused such destruction around the Eastern Mediterranean in the late 13th century BCE. But questions and theories of population displacement go back further; new studies of the sudden flooding of the land basin that is now the Black Sea (expanded from a lake ca. 8,400 years ago) suggest the resulting refugees became the farmers of Macedonia and northern Greece, a theory some scholars link to the true origins of the deluge behind Noah’s legendary ark, or perhaps to the myth of Deucalion and Pyrrha.38

A fragmented synoikismos (synoecism) – a population amalgam – existed through the Helladic period and Greek Dark Ages (ca. 1100-850 BCE) before the city-state culture of the Archaic period (ca. 800-480 BCE), and it resulted in a dioikismos of independent communities in which symbola, the rudimentary agreements between pairs of states, nevertheless, provided a basis for trade and law between the ethnic groups.39 Tribal identity was then far more relevant than today’s homogenised terms, possibly because linguistic palaeontology does provide overwhelming evidence of a ‘pre-Greek’ population inhabiting the region: the names Corinth (Korinthos), Knossos, Larissa, Samos, Mycenae (Mykenai) and Olympus even, are thought to be of pre-Hellenic construction. The name Cadmus (Kadmos), the legendary Phoenician founder of Thebes who introduced the alphabet into Greece, is also considered pre-Greek.40

The Latin term Graecus and the land of Graecia developed later, perhaps from the Graikoi who assisted the citizens of Euboea to migrate to Cumae in Italy through Epirus in the 8th century BCE; they were from the ancient city of Graia linked to Tanagraia, the daughter of Asopus (and so to the eponymous city of Tanagra and to Oropus), by Hesiod, Homer, Aristotle and Pausanias after them. According to Aristotle and the Parian Chronicle it was the Graikoi who were the renamed Hellenes, though early attachments still restricted them to Epirus and the Dodona region and its Homeric links to the age of Odysseus and Achilles. Hesiod referred to this region as Hellopia and Stephanus of Byzantium later named Graikos as the son of Thessalus the woodcutter who was first shown the shrine at Dodona dedicated to the cult of Zeus Naos.41

In time, the Romans, whose early continuous contact was likely with northwestern Greece, came to term Hellenes (now meaning all Greeks) Graeci.42 In return, the Greeks were partly responsible for the widening use of the appellation Italia; it stemmed from the Latin for ‘land of calves’ or ‘cattle’ (calf, vitulus), thus Vitalia. Lacking a ‘v’ in their alphabet, the Greeks in southern Italy settled on a name that spread north from Calabria and was eventually adopted by Rome itself. Some 600 years on from Alexander’s day, both the Greeks and the Italians of the Eastern Roman Empire were to become grouped together as the Rhomaioi, Romhellenes and the Graecoromans of a new Byzantine Empire.

Outside Greece’s borders were the barbaroi. The verb barbarizein described the imitation of non-Greek sounds and followed Homer’s use of barbarophonoi for those of incomprehensible speech.43 In Plato’s view, much of it adopted by Aristotle, barbarians were ‘more servile in their nature than the Hellenes, and the Asiatics more than the Europeans’, and thus they ‘deserve to be slaves’, though curiously, Aristotle put this differentiation down to climate; in his Politics, Aristotle even seems to have implied that the Macedonians, alongside the Celts and Scythians, were barbarians too, whilst Isocrates (ca. 436-338 BCE) likened the Greek-barbarian divide to nothing short of that between mankind and beasts.44

The ‘closed world’ of some 750-1,000 introspective and independent mainland Greek poleis, city-states (originally ‘strongholds’), had acted as a natural buffer to the integration of barbarians and to the concept of national monarchy as well, unlike the development of Greece’s northern neighbours.45 But the need for foreign commodities meant a polis could never remain totally isolated, thus the appearance of 300 or so Greek settlements overseas where they had to live side-by-side with the indigenous population and probably developed a less xenophobic attitude as a result.

The Greeks, and later the Romans, repeatedly referred to all northern barbarian tribes (including the Goths) as ‘Scythians’ or ‘Thracians’.46 Thucydides considered the Acarnanians, Aetolians, Epirotes – the northern Greek tribes – and Upper Macedonians (more akin to the ethne of the Epirotes, thus Molossic) as barbarians, though he did distinguish ‘proper Macedonians’ (the ‘Lower Macedonians’) from the Balkan tribes to the north (as did Ephorus of Cyme ca. 405-330 BCE); it was these upper cantons (including Paeonia, Pelagonia, Lyncestis, Orestis, Eordaea, Elimea, Tymphaea and Almopia) that Alexander’s father, Philip II, effectively absorbed into a ‘greater Macedonia’.47 Polybius (ca. 200-118 BCE), who once implied the Romans were a tribe of barbaroi as part of a (long) rebuttal to his forerunner, the historian Timaeus (ca. 345-250 BCE), provided a more nuanced distinction of ethnicity, and it appears that by his day (the 2nd century BCE) the widespread use of Hellenistic koine (a dialect) had begun to break down the ancient divides.48

Defying the older Homeric-era definitions, Alexander may indeed have been an original kosmopolites, a self-declared ‘citizen of the world’, a term that first became attached to Diogenes the Cynic who he famously met in Corinth. For political purposes Alexander might have presented himself as philhellenos, the cognomen taken by his Temenid predecessor, King Alexander I (ruled ca. 498-454 BCE), though the titles Proxenos and Euergetes (‘guest-friend’ and ‘benefactor’) granted by Athens to King Archelaus I (ruled Macedonia 413-399 BCE, his name broadly meaning ‘leader of men’), were hardly likely to have come Alexander’s way now that Greece was garrisoned.49 Macedonia itself had been infused with foreign settlers through tribal and city state migrations and the displacement of war: when Mycenae was destroyed by Argos, over half the population relocated to Macedonia on the invitation of Alexander I.50 Justin summed up Philip II’s own empire forging and repopulating in more recent times:

The cantons of ancient Macedonia.

On his return to his kingdom, as shepherds drive their flocks sometimes into winter, sometimes into summer pastures, so he transplanted people and cities hither and thither, according to his caprice… Some people he planted upon the frontiers of his kingdom to oppose his enemies; others he settled at the extremities of it. Some, whom he had taken prisoner in war, he distributed among certain cities to fill up the number of inhabitants; and thus, out of various tribes and nations, he formed one kingdom and people.51

If, as a result, Alexander’s view on ethne was even something more eclectic that defied autochthonous norms, it was his ancestral Greek origins that would have rooted him in a distinct cultural upbringing with its vow to excellence and a particular honour code that backboned the Homeric sagas.

But there remains an ongoing philological contention over the original language of the Macedonians, and this stems in part from dialogues within the Alexander histories. As far as Thucydides was concerned, the region had previously been culturally backward (‘a majority of unwalled villages federated into ethne’) and probably linguistically distinct from the population to the south that spoke the more refined Attikoi (Attic) dialect of Greece.52 This is backed up by Curtius’ description of the trial of Philotas, the son of Alexander’s prominent general, Parmenio, for it suggested ‘legal’ procedures were conducted in a tongue (or dialect at least) distinct from the Greek that Alexander’s top echelons apparently spoke.53 Philotas replied that he wished to use the language Alexander had adopted (aedem lingua), rather than the patrius sermo that Curtius’ Latin text referred to, in order that the greatest number of soldiers could understand his defence; the ‘mother tongue’, Philotas stated, had become obsolete because of the wider dialogue with foreign nations. As Edward Anson concluded, Philotas’ practical retort indicates the Macedonians could understand Attic Greek more easily than Greeks could grasp Macedonian.54 The common ‘adopted’ dialect being referred to (aedem lingua) was most likely akin to Hellenistic koine (which became known as ‘Macedonian’ Greek) rather than Attic Greek, for the Ionic dialect (with perhaps an admix of others) which was later infiltrated by Macedonian, was the basis of the lingua franca prevalent in much of the early Hellenistic world.55

Plutarch believed that in cases of extreme emergency Alexander did beckon his Bodyguards in makedonisti, so ‘in the Macedonian tongue’.56 The contention is backed up by a fragment found at Oxyrhynchus (Egypt) by archaeologist Annibale Evaristo Breccia in 1932; it described the clash between Eumenes of Cardia (the former royal secretary, now a governor and general in the post-Alexander world) and the Molossian noble, Neoptolemus, in the early Successor Wars during which Xennias, ‘a man of Macedonian speech’, was sent out to intimidate the opposing ranks.57 Of course the claim may have been made by a historian emphasising Eumenes’ Greek disadvantage, and the historian Hieronymus, his client, cannot be discounted as the architect of that. We have a similar anomaly in Plutarch’s Life of Eumenes when the Macedones were portrayed as saluting their fever-ridden general: ‘… they hailed him at once in their Macedonian speech, caught up their shields, beat upon them with their spears, and raised their battle-cry…’58

But noting statements from the Roman chronicler Livy (64/59 BCE-17 CE) and earlier from Herodotus that Greeks and Macedonians shared a common tongue, and with scant references in the texts to makedonizein, ‘to speak Macedonian’, scholars remain split on the case for a national language. A middle ground concludes that the Upper Macedonia cantons to the north and west, which Hatzopoulos terms ‘the cradle of the Macedonian ethnos’, were linguistically distinct from the Lower Macedonian heartlands, the flat fertile plain bordering the Thermaic Gulf, which included Bottiaea (possibly settled by Cretans in the Late Bronze Age ca. 1300 BCE) and Pieria.59 The upper cantons had perhaps adopted the harsh Doric of northwest Greece as suggested by the Pellan Curse Tablet.60

If taken at face value, episodes suggest that any diglossia that had existed in Macedonia rested with the nobility, and not with the peasant-conscripted infantry. Yet a formal approbation, national war cry, or a judicial procedure such as the trial described above, may indeed have followed archaic procedures rooted in the old tribal dialect that retained (or shared) elements of Illyrian, Phrygian and Thracian, which were evidenced by the lexicographer Hesychius of Alexandria in the 5th century.61 As a parallel, we might note that the judicial language of Solon’s legislative reforms of 5th century BCE Athens was sufficiently archaic to cause interpretive problems for later classical-era scholars.

The graves unearthed at Vergina dating back to the 5th century BCE indicate inhabitants had certainly adopted Hellenic names by then; of the 6,300 inscriptions found in the former state borders, ninety-nine per cent were written in Greek. In contrast, Hatzopoulos notes that ‘a relatively high percentage of the names attested in the neighbouring lands conquered after 479 BCE are of pre-Greek origin’; this suggests the vanquished were not immediately displaced and for a time retained their ethnicity.62 But there can be no doubt that Macedonia, though regionally discrete and perhaps tribally distinct, was by the 5th century BCE certainly a part of the Greek cultural milieu,63 by which point it is likely that foreign policy and out-of-state business was conducted in Attic Greek, though Attic Greek, in turn, would be infiltrated by elements of Macedonian in time.64

If we need any proof that the reform-minded Macedonian monarchs like Alexander I, Perdiccas II (reigned ca. 448-413 BCE) and Archelaus I were modelling their cultural sophistication on Greece, we only have to recall that the great tragedian Euripides, Hippocrates of Kos (ca. 460-370 BCE) the ‘father of western medicine’, the revered Pindar of Thebes (ca. 518-433 BCE), the dithyrambic poet Melanippides and Bacchylides the lyric poet, Choerilus the epic poet and Agathon the tragic poet along with his lover Pausanias, were all invited to stay at the royal court at Aegae or at the new capital at Pella. So was the musician Timotheus, alongside Zeuxis who captured life on canvas like none before him, and the historian Hellanicus of Mytilene who as colourfully captured lives on parchment.65

Foreign hetairoi (high-ranking court friends) were given substantial tracts of land in Macedonia and many ended up drinking at symposia, the banquets (komoi or deipnoi) typical of the Macedonian court.66 Guests typically relaxed on the Greek-styled couch, the kline, and famously downed their wine neat, akratos, and judging from the outcomes they consumed more than the Spartans’ daily ration of two kontylae per soldier which had helped to wash down their notorious melas zoomos, Sparta’s black bean soup (with boiled pork, blood and vinegar) that Leonidas, Alexander’s stricter teacher, might well have introduced him to as a youth.67

Herodotus is thought to have ‘stayed with the king of the Macedonians in the time of Euripides and Sophocles’ (ca. 480 and 497-406 BCE respectively), whilst Aristotle’s own father, Nicomachus, had been a state doctor to Amyntas III (reigned 393/392-370 BCE), the father of Philip II.68 Although Socrates (ca. 470-399 BCE) is said to have declined an invitation to the state, Euphraus, the philosophising student of Plato, visited and taught at the court of Perdiccas III, Philip’s older brother; it was, in fact, Euphraus who advised Perdiccas to give the teenage Philip II a district to cut his teeth in governance.

The Greek comedy playwrights of the period made references to the lavish Macedonian court banquets and weddings that were the envy of the Athenians. Actors, such as the celebrated Neoptolemus and Philocrates were even sent as diplomats to Philip, so aware were they of his philanthropia to performers; in this particular case, as a precursor to what is now termed the ‘Peace of Philocrates’ of 346 BCE, the anti-Macedonian Athenian orator Demosthenes accused the hypocrites (actor) Neoptolemus of ‘acting’ in the best interest of Philip rather than Athens. Opposing Demosthenes to the end of his career, the Macedonia-friendly orator Aeschines, also present as part of the embassy, was a former actor himself.69

The emerging power of Macedonia had hardly gone unnoticed; Plato certainly took an interest and Thucydides appears to have been an admirer of the growing state (he owned property in the Strymon basin); the historians Theopompus and Anaximenes of Lampsacus (ca. 380-320 BCE), possibly encouraged by Isocrates, spent time at the Pellan court of Philip II, as, of course, did Aristotle who would uniquely influence his son; Aristotle’s student Theophrastus (who became an expert on plants) was to later advise on land reclamation nearby.70 The Argead kings, if not quite ready to adopt the ‘people power’ of demokratia, had ambitions on becoming civilised in all other ways, especially now that the ‘Aegean façade’ of Lower Macedonia had integrated itself into the ‘international, economic, diplomatic and cultural world of its times’.71

This newly ‘united’ and monarchic Macedonia was a ‘sub-Homeric enclave’ in which citizens started adding Makedon to their names as a sign of a national identity, suggesting there existed an extraordinary legal homogeneity under the late Argead kings. This was something of a paradox to a still-fragmented Greek mainland, a state of affairs epitomised by the almost simultaneous call from Isocrates for Philip II to lead a ‘Panhellenic’ expedition against ‘barbarian’ Persia, and a reply from Demosthenes which rallied Athens to oppose the ‘barbarian’ Macedonian king.72

Something of that paradox resurfaced in Alexander who was mentally fused to the past through syngeneia (kinship) and lineage to the heroes of Hellas and the venerated kings of antiquity: ‘For what is the worth of human life, unless it is woven into the life of our ancestors by the records of history?’73 He was acutely aware of being porphyrogennetos with an illustrious crossbreeding, and just as mindful of how that imagery could be exploited. ‘Alexander’ broadly translates as ‘repeller’ or ‘defender’ of men, and it was a name fit for cause.74 He appears to have genuinely believed in his alleged descent from heroes, and his training had been far more illustrious than the encyclios paideia, the general classical Greek education. The poems of the Trojan Epic Cycle became his Omphalos, or as Alexander liked to term them, his ‘campaign equipment’ or viaticum.75 But surely the keenest blade in his Homeric arsenal was Odysseus’ declaration: ‘Let there be one ruler and one king!’76

Alexander’s birth was heralded as divine. Hegesias the Magnesian (fl. ca. 300 BCE), founder of the ‘Asiatic style’ of composition, proposed that the great fire at Ephesus in 356 BCE could be explained on the basis that the goddess was absent from her temple attending his delivery, for the events had apparently coincided; Plutarch wasn’t impressed with the connection, terming it ‘a joke flat enough to have put out the fire’.77 Yet Parmenio’s defeat of the Illyrians and Philip’s recent capture of Potidaea, along with the victory of his racehorse at the Olympic Games, made the day Philip heard that a son had been born to him, indeed seem rather auspicious.

Alexander’s mother, Olympias, initiated into the Dionysiac mysteries of the Clodones and Mimallones (the Maenads, ‘raving ones’, of Greece linked to Orpheus whose grave was located in Macedonia), was from the Molossian tribe of Epirus.78 Through her, Alexander managed to claim Aeacid descent from Achilles, whose son, Neoptolemus (also known as Pyrrhus of the Pyrrhidae), according to legend, had once ruled the region.79 Through him, and as popularised in the Andromache of Euripides who spent his final years in Macedonia, Alexander was also a descendant of Hector’s widow, the Trojan princess Andromache, who became Neoptolemus’ concubine and gave birth to Molossus, the founder of the eponymous Epirote tribe; the ancestry linked Alexander to both the attackers and defenders of Troy.80 As a result, as Bosworth points out, he did not view Trojans as barbarians but as ‘Hellenes on Asian soil’, which rather underpins Homer’s own linguistic treatment of Priam’s men and Dardanus’ mythological roots. In Alexander’s invasion of Asia, the united blood of Achilles and Priam would finally campaign together.81

Arrian associated Alexander with the hero Perseus, the son of Zeus, and the father of both the Persian race and the Greek Dorians through Heracles; this helps explain the similarities between the Greek Succession Myth and the Babylonian equivalent, the Enûma Elis.82 From his reading of Herodotus, Alexander would have been aware that King Midas, adopted by the childless Gordias, and the founder of the Phrygian dynasty, was said to have emerged from a region of Macedonia though the Roman geographer, Strabo (literally, ‘squint-eyed’, 64/63 BCE-24 CE), thought the Phrygians, originally Bryges or Brigians, were a Thracian tribe. Midas’ wealth came from mining iron ore until he was expelled by the semi-mythical Caranus (‘Billy-goat’), ‘the founding father of Macedonia’ who in legend reigned ca. 808-778 BCE. The Gardens of Midas at the foot of Mount Bermion still carried his name in Alexander’s day.83 This dominant Phrygian tribe, which migrated across to Asia Minor (ca. 800 BCE, though claims dating to as early as 1200 BCE suggest they broke Hittite power), inhabited the early tombs at Aegae found under some 300 of the tumuli, and it is worth noting that in Euripides’ Helen the Trojans are referred to as ‘Phrygians’.84

The opening lines of Plutarch’s biography additionally managed to trace Alexander’s descent (through the Heraclid line of his father) back to the ‘founding father’, Caranus, who originally hailed from Argos and invaded Macedonia ‘with a great multitude of Greeks’.85 This enabled Alexander to trace his lineage to the Argive Heracleidae and back to Danaus and the Danaans who shipped to Troy, the heritage Isocrates had assigned to Philip.86 Other Heraclids included the kings of Sparta and the Aleuadae dynasty of Larissa in Thessaly (Heracles’ supposed birthplace), and so by definition their relatives, care of their common forefather, Heracles Patroos.87

Euripides, once described as ‘the first psychologist’, had a different idea altogether: to please his reform-minded host, he proposed it had been an earlier Archelaus, a son of Temenus, who anticipated the Temenids, encapsulating the new proposition in a play aptly named Archelaus.88 Adding to the thickening founding fog was a parallel belief that the etymological roots of the Argeads lay in ‘Argives’ who were Dorians in Greek tradition, as this challenged the claims that the stemma actually derived from ‘Argaeus’ the son of King Perdiccas I, or, according to later writers, a son of Macedon.89 Appian (ca. 95-165 CE), writing later from the safe distance of Roman Alexandria, more controversially claimed that the true origins of the name of the Macedonian royal clan might have stemmed from a far more rural Argos in the Macedonian canton of Orestis; if so, it had been expediently hidden beneath layers of court-sponsored propaganda.90

Hellanicus of Mytilene, who also spent time at the Macedonian court (probably in the reign of Archelaus), positioned a Macednus (not Macedon) as the son of Aeolus, so from the direct line of Hellen with ancestry to the Aeolians and Dorians, thus firmly ‘Hellenic’; Herodotus, who treated geography and ethnology as one, supported the Dorian links and claimed that Alexander I, the first Argead to mint coins, had convinced the adjudicating hellanodikai, the official judges from Elis, of his Peloponnesian Argive roots so that he might compete in the Olympic Games; his entry resulted in victory in the furlong foot race ca. 495 BCE. It has been more recently suggested that the increasingly pro-Hellenic stance of the Macedonian court resulted in the kings adopting the Greek names conspicuously found on the Vergina graves.91

To anchor down these polymorphic lineages, Philip and Alexander minted a new bimetallic currency system, stamping images of Zeus crowned with laurel and Apollo on gold Philippeioi, while Heracles appeared on silver tetradrachms; and here, anew, was allos houtos Heracles, the hero ‘reborn’, as the Greek proverb suggested.92 Philip’s ‘sacred wars’ in Greece in Apollo’s name had already forged the attachment and the imagery of success was stamped on his coinage in both the Attic and Thraco-Macedonian standards for circulatory effect: it included Philip’s three chariot victories at the Olympic Games showing a youth on horseback and, suitably, a chariot.93

The first of Alexander’s own silver coins; a tetradrachm struck sometime between ca. 335-29 BCE. Minted in Pella, it still displays the laureate head of his father, Philip II. On the obverse is a nude youth holding a palm frond and reins on horseback with a kantharos (a deep double-handed drinking vessel) below. Images provided with the kind permission of the Classical Numismatic Group. Inc. www.cngcoins.com.

A late Alexander tetradrachm minted at Sardis, the well-guarded treasury, under its governor Menander ca. 324 BCE. It bears a head of Heracles wearing a lion skin, and Zeus Aetophoros (‘Eagle-bearer’) with a club is seated on the obverse.

Philip and Alexander had commissioned portraits and bronzes by Lysippus and Euphranor before the planned Persian campaign. The family statues Philip commissioned from Leochares and erected in chryselephantine (or possibly marble) in the circular Philippeion in the precinct of Zeus at Olympia suggest the early birth of the Argead public relations machine, as well as an attempt of reconciliation with a then alienated son and wife.94 Epic lineages were ever sought after by kings and their court poets, but here the Argeads were creating a new Succession Myth, and as history was to show, they became every bit as brutal as the Titans from whom they professedly descended.95

Backed by this useful polytheism, these heritages implied a telegony in which their combined traits and bloodlines would converge and meet in a new demigod: Alexander himself. They gave him his entelekheia, the vital force that completed him and then compelled him to Persia in his father’s stead. Although heritages were clearly often fused, confused and conveniently manipulated, the one ancestor that Alexander was never able to comfortably integrate into his developing persona was his own father, Philip, murdered at Aegae when Alexander was aged twenty, for he had provided the legitimacy that Alexander needed, but not the identity he ultimately sought. And as a recent study concluded, once the memory of Philip began to develop into nostalgic myth, Alexander lost control over its subordination to him.96

A reconstruction of ancient Olympia from Pierers Universal-Lexicon, 1891. The circular building in the left corner is the Philippeion housing the statues of Philip’s family.

‘THE GIVER OF THE BRIDE, THE BRIDEGROOM, AND THE BRIDE’97

There were both immediate and lingering rumours that Alexander had played a part in his father’s death, and they, in turn, were fuelled by Philip’s accusations of Olympias’ infidelity (so claimed Justin, who also stated that Philip divorced her – Arrian claimed he ‘rejected’ her), and that would have been tantamount to Philip disowning his son.98 Badian went as far as suggesting the previous rift between the prince and king had resulted in Philip favouring Amyntas Perdicca, the son of his older brother, Perdiccas III, in the line of succession; Philip had ostensibly ‘managed’ Amyntas’ kingship due to his nephew’s youth and more recently he had married him to his daughter, Cynnane, Alexander’s half-sister.

Plutarch believed the Macedonians themselves were inclining to Amyntas and to the sons of Aeropus of Lyncestis (who had a claim to the throne through an older branch of the royal house) at Philip’s death. Alexander had two of the latter (Heromenes and Arrhabaeus) immediately executed, and soon after, Amyntas as well, to secure his position. The exception was the superficially compliant third son of Aeropus, Alexander Lyncestis, married to a daughter of the now all-important Antipater, previously Philip’s foremost general and the regent in his absences.99 Plutarch summarised the court position at the time:

All Macedonia was festering with revolt and looking toward Amyntas and the children of Aeropus; the Illyrians were again rebelling, and trouble with the Scythians was impending for their Macedonian neighbours, who were in the throes of political change; Persian gold flowed freely through the hands of the popular leaders everywhere, and helped to rouse the Peloponnese; Philip’s treasuries were bare of money, and in addition there was owing a loan of two hundred talents…100

Along with ‘the accomplices in the murder’ who were summarily executed on Alexander’s orders ‘at the tumulus of Philip’, those upon whom regicidal suspicion fell (genuine or contrived) would have suffered a similar fate, either publicly, or behind the scenes.

Several events which took place in close succession contributed to the patricidal finger pointing: Philip had recently married Cleopatra, the young niece (Diodorus and Justin said ‘sister’) of the influential Macedonian baron, Attalus, who had prayed for a ‘legitimate heir’ from the union; that was a barbed reminder to Alexander, who apparently threw his goblet at him during the court banquet where the toast was made, that he was half Epirote, or indeed a product of Olympias’ infidelity.101 Philip had his sword drawn as he lurched drunkenly towards his unapologetic son who then called into question his father’s ability to lead the invasion of Asia. The incident precipitated the flight of Olympias to her home in Epirus, while Alexander journeyed to Illyria, probably to his friend and ally, the Agrianian king, Langarus. That is exactly where you would go to raise a hostile force to oust a Pellan king, for the Illyrians had managed exactly that before.102

The teenage Cleopatra was now pregnant with Philip’s heir; she gave birth to a daughter, Europa, just days before Philip’s death and there was possibly an earlier son named Caranus; they were murdered by Olympias, probably with the blessing of Alexander (despite claims otherwise), within the year.103 Moreover, at the time of the wedding of Philip and Cleopatra, Alexander had reached throne age, eighteen.

The rift between Alexander and his father appears to have run deeper still. In preparation for his invasion of Asia, Philip had (earlier) reached out to Hermias of Atarneus (with whom Aristotle had resided), and to Pixodarus of the Carian Hecatomnid dynasty – the ‘grandest’ in the Eastern Mediterranean and influential in Lycia – to arrange a royal marriage for an alliance on the coast of Asia Minor. Perhaps when still in his self-imposed exile in Illyria, Alexander had undermined the proposed pairing of his half-witted half-brother, Arrhidaeus, to Pixodarus’ daughter, by offering himself instead; it was Parmenio’s son Philotas who possibly revealed the plot to Philip, and he was apparently a marked man thereafter.104 Some have interpreted from the episode that Alexander already had plans to lead the invasion of Asia in his father’s stead. His recent impetuous founding of Alexandropolis in 340 BCE (when Philip was busy besieging Byzantium) after campaigning in Thrace at the age of just sixteen, was a testament to the prince’s own ambition, and it may have left his father wary despite Plutarch’s claim that he ‘was excessively fond of his son, so that he even rejoiced to hear the Macedonians call Alexander their king, but Philip their general.’105

Justin painted a more hostile picture of court affairs: after the initial rift with Philip, Olympias urged her brother, Alexander Molossus, now the Epirote king, to declare war; it would have been an opportune moment with Philip’s most effective generals, Parmenio and Attalus (Cleopatra’s uncle), absent in Asia with a significant part of the royal army which was establishing a bridgehead for the invasion. At this point Alexander’s envoy, Thessalus, was to be found in Corinth potentially seeking military Greek support for the prince. Philip’s oikos (household) was clearly in trouble, and only the diplomacy of Demaratus of Corinth managed to reconcile father and a son who then became Master of the Royal Seal.106

Astute as ever in a political crisis, Philip paired Alexander’s sister, Cleopatra, to Molossus to stave off any Epirote threat; he ‘disarmed him as a son-in-law’, as Justin put it.107 Nevertheless, he sent Alexander’s philoi (closest court friends) including Ptolemy (the future Egyptian dynast), Nearchus, Laomedon and Harpalus (with his older brother Erygius) into exile. Those broadly coeval with Alexander were syntropoi (literally ‘those eating together’) who would later become the megistoi, the ‘great men’, who frequented his court. Staging the wedding would be the last performance of Philip’s twenty-three-year reign, for he was stabbed by Pausanias of Orestis upon entering the amphitheatre at Aegae.108 The day signified Alexander’s arrival; it was perhaps even a day he orchestrated himself. Alexander took up the reins of power as keenly as he is said to have mounted his Thessalian warhorse, Bucephalus, and he and Olympias didn’t hesitate in executing the rivals for the throne, most likely along with their families and their political backers as well.109

Pausanias was pursued by Alexander’s close court friends, Perdiccas and Leonnatus, and by the royal page Attalus, and was conveniently murdered before he could be questioned; the murderer and his pursuers were all from the canton of Orestis and both Perdiccas and Leonnatus became Alexander’s personal Bodyguards, Somatophylakes, on campaign.110 Pausanias had allegedly confronted Alexander with the same grievance he had previously taken to Philip – sexual assault – and he received, as Alexander’s reported reply, the line from Euripides’ Medea: ‘the giver of the bride, the bridegroom, and the bride’; it hinted of a triple murder in the making, and one that did come to pass (at Philip’s death, Alexander executed the ‘giver’, Attalus, and Olympias murdered the bride, Cleopatra). Justin claimed Olympias had arranged the getaway horses for the assassins.111

Possibly to distance himself from any further implication of guilt, Alexander ‘took every possible care over the burial of his parent’ at a time when he needed all the support he could muster.112 Within two years, and having ‘re-subdued’ Greece, Thrace and the Balkans, Alexander crossed the Hellespont (Hellespontos, ‘Sea of Helle’), today’s Dardanelles (named after Dardanus), in his father’s place, and he bolstered support for the invasion by claiming Philip’s assassins were backed by Persian gold. We will never know if Alexander fully dismantled the stigma of parricide, but an alleged oracular reply at Siwa some three years on, confirming all Philip’s killers had been punished, sounds suspiciously like a contrived vote on his own innocence, though it was peculiarly exonerating to the still-at-large Persian Great King as well.113

The two previous invasions of Greece by Persia under Darius I (ended 490 BCE) and his son Xerxes I (ended 480 BCE) had not been sudden appearances of Persian power and influence in Europe. Macedonia of the 6th century BCE was, as Borza termed it, a ‘dependency of the Persian Empire’, after which the autonomous vassal kingdom was formally occupied as Darius’ forces under Mardonius spread west across the Hellespont in 492 BCE. The occupation and the tribute lasted until 479 BCE when Xerxes was forced to withdraw after three decades of Persian control which had nevertheless helped their client kings, Amyntas I, and then his son Alexander I, subjugate a hinterland that would become ‘Upper Macedonia’; also absorbed were lands to the west into an expanded Lower Macedonia.

Alexander I had prudently and ingeniously managed to play a ‘double game with great skill’; chosen by Mardonius to offer seductive terms to Athens to fracture Greek resistance, he provided the Persians with support at Plataea, yet timber for the Greek fleet, and he covertly spied for the allied forces to warn them of imminent Persian attack, eventually falling on a large body of the retreating Asiatic army.114 Macedonia’s hinterland and the Athos peninsula provided much-needed wood (pine, silver fir and four types of oak) to the Athenian shipbuilding trade and alliances (often short) with Athens were driven by this dependence.115 To counter any suggestion of exploitation in the war, Alexander I next dedicated a golden statue of himself at Delphi and Olympia, with the result that Pindar termed him ‘the bold scheming son of Amyntas’. His son, Perdiccas II, was to change sides even more frequently in the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE); a century and a half later a no less scheming Philip II played a similar diplomatic game and was once aligned with Artaxerxes III, sending expediently supportive messages to the Persian court.116

Persian occupation left its mark on Macedonia and perhaps on Alexander III as well; the term ‘satrap’ we see in the campaign histories relating to Alexander’s regional governors, stemmed from the Achaemenid rule of an empire managed through client kings and officials who maintained the pax Persika. It has been proposed that the late Argead tradition of enrolling royal pages (paides basilikos, ‘informal hostage sons’ of the Upper Macedonian nobles), as well as the formal polygamy of the Argead (and Molossian) kings, who had their own military units of ‘friends’ (hetairoi), were also of Persian origin, and some commentators argue that the melophoroi, the golden apple-bearing Persian Immortals, were the inspiration behind the Macedonian agema of the hypaspists, the royal guard.117 Somatophylakes, the king’s personal Bodyguards, as well as chiliarchos, likened to post of the Achaemenid hazarapti (a second-in-command who also had administrative and diplomatic responsibilities like chief usher and the king’s intermediary with messengers) and reintroduced by Alexander (and occupied by his closest companion Hephaestion, and assumed by Perdiccas after him), were titles or roles adopted (or adapted) from the Persian courts, it is believed. Even the position of the king’s cupbearer had its origins with the Achaemenid kings.118

Compared to the ‘old guard’ command – the seasoned campaigners and infantry generals Alexander inherited from his father – the Bodyguards represented a class of relatively young equestrian aristocrats expected to adhere to the kalos kagathos of classical Greece, the Homeric-rooted code of virtue and honour.119 In fact the Homeric poems have been termed nothing less than the Bible of the Greeks containing ‘the germs of all Greek philosophy’.120 Alexander’s Bodyguard corps emerged from the syntrophoi raised at the king’s court in Pella, the ‘city of stone’.121 If broadly coeval, they too would have been familiar with, or even educated with Alexander under the tutelage of Aristotle. Along with other trusted generals and leading landowners, they formed the noble ‘cavalry’ class of Macedonia, which attended the synedria, the gatherings of the king’s Privy Council and advisers. In the absence of what we might today term a ‘middle class’, Macedonian nobles commanded both the cavalry and the infantry battalions that were formed from tenant farmers and herders who responded to the king’s call, and who made up a professional standing army that first appeared under Philipp II.122

Hellas, and especially Macedonia, had been fascinated with tales of the Persian dynasty with its fabled court wealth which still pulled influential strings across the Aegean; at one time over 300 Greeks frequented the Achaemenid court and some even attended the Great Kings as physicians. Inscriptions dating to the reign of Darius I confirm the presence of Ionian and Carian stonecutters working on the new palace constructions, and the Greek cities of the Asia Minor seaboard acted as information conduits and contact points with the Persian administration.123

It is no wonder, then, that the Greeks had tried to link the ancient East with their own mythology once they appreciated its greater antiquity; they accepted African and Asian origins for the ancestries established by Medea, Perseus and the Achaeans, which appears a paradoxical sociality considering their proud autochthonism.124 Cadmus, Pelops, Danaos and Aegyptus all arrived in Greece from Asia and Egypt in the founding myths.125 As Nietzsche put it, ‘… Their culture was for a long time a chaos of foreign forms and ideas – Semitic, Babylonian, Lydian and Egyptian – and their religion a battle of all the gods of the East…’ Xerxes had exploited just that when he too reminded Greece of the Persian-Perseus link when garnering Argive support for his pending invasion.126

In Greek literature the term ‘Persian’ was employed loosely, as was its geographic and dynastic association. In the Alexander histories we see the Great King’s vassals referred to as Iranian, Asiatic and Oriental, as well as Median, beside Persian. Cyrus and Darius I were additionally termed kings of Assyria (often shortened to ‘Syria’ by Diodorus), the breadth of which might unite Assyrian Nineveh, Mesopotamia (Greek in origin, from mesos ‘middle’ and potamos ‘river’) and Babylonia. The ambiguity has caused much confusion for historians;127 Herodotus and Xenophon used ‘Assyria’ when referring to regions as diverse as Anatolia to the Black Sea and the Aramaic Mesopotamian lands, where Curtius at times referred to the region of ‘Lydia’ in a manner that recalled the old kingdom of the expanded state, thus Asia Minor west of the Halys river.128 Unable to untwine these knotted threads, we will defer to simply using ‘Persian’ when regional appellations and ethnographies remain less than well defined, and refer to their inhabitants as ‘Asiatic’ where their origins are mixed or contested.

Herodotus, faced with the task of combining ‘oriental dynasties with Greek genealogies in the first attempt at international chronology’,129 and Ctesias, himself a physician to Great King Artaxerxes II (Artaxšaçā in Old Persian), argued over the conflicting traditions behind the Achaemenid dynasty founded by Cyrus I and which endured from 539 to 330 BCE, ending with Alexander’s defeat of Darius III. Originally named ‘Artashata’ in Persia and Kodommanos (Latinised, Codommanus) to the Greeks, ‘Darius’ originated as something approximating ‘Darayavaus of the haxamanisiya’ in Old Iranian. Yet the founder of the line, Achaemenes, was as mythical as Romulus, the legendary founder of Rome. Cyrus the Great was an Elamite described as half-Median – Xenophon confirmed his Median roots through Astyages and his Perseidae origins from Cambyses130 – though ‘Cyrus’ is a Latinised-Greek derivative descended from Old Persian (Kūruš) with Elamite and Assyrian overtones, the meaning of which is still debated, though Plutarch claimed it was the Persian word for ‘sun’.131

The tombs at Naqsh-e Rustam (close to Persepolis), and that identified as Darius I’s, in particular, among other less-legible inscriptions at the necropolis, along with the relief at Behistun (Bastagana in Persian, ‘place of god’), are rich in multi-lingual engravings referring to the conquests of the Great Kings. Cuneiform syllabary often placed Elamite beside Akkadian as well as Old Persian – the languages that later transmuted into the more broadly used Parsi and written in Aramaic script.132 Like the bilingual and trilingual stone inscriptions of the Ptolemies, these provide us with ‘rosetta stones’ of rare linguistic clarity.133

To the Persians the Hellenes were Yauna, Ionians, though it seems Yauna takabara specifically referred to Macedonians and possibly because of their distinctive felt hats, the traditional flat kausiai, that would now be seen across the empire as Alexander’s army marched east.134

The 50 x 82 feet Behistun Inscription of Darius I carved sometime in his reign ca. 522-486 BCE. The multi-lingual texts in Old Persian, Elamite and Babylonian recorded Darius’ lineage and battles through the upheaval caused by the deaths of his predecessors, Cyrus the Great and his son, Cambyses.

ATHLIOS PAR’ ATHLIOU DI’ ATHLIOU PROS ATHLION: THE GRUDGING FACE OF FEALTY

Scholars have noted that from the beginning of the Asian campaign Alexander ‘acted not merely as a conqueror, but as the rightful heir’ to the Persian royal line.135 Quite possibly he saw the Asian hinterland as a ‘Pantheon’ for installing the legend that would underpin the new anabasis, his journey into the Asian interior. In Tarn’s opinion ‘the primary reason that Alexander invaded Persia was, no doubt, that he never thought of not doing it; it was his inheritance’, as were the vast lands that lay across the Hellespont.136

‘Persuasion through words is not a characteristic of kings but of orators’,137 and as early as 330 BCE, as Alexander ventured into the heart of the Persian Empire, Demosthenes’ On the Crown made a scathing declaration to Aeschines, the philomakedon, on the extent of Macedonian continued domination in Greece.138 Having subdued Greece in the wake of his father’s death, Alexander was confirmed as hegemon (literally the ‘dominant one’), or in the military context, strategos autokrator, of the League of Corinth,139 a federation which represented to koinon ton Hellenon, the community of Greeks and their Defenders of the Peace. He inherited two seats on the Amphictionic Council and life archonship of the Thessalian League, as Philip had before him, deftly holding measuring scales in one hand and a dagger in the other, like Themis and her divine justice.140 For the Macedonian court at Pella was ‘freeing’ Greece from the Persian yoke and yet holding the sword of Damocles over the kyria ekklesia, the treasured assembly meeting that kept Athenian demokratia (literally ‘people power’) alive and vocal from the Pnyx.141

He left behind him a smouldering resentment despite the oath sworn by its members under the Treaty of the Common Peace, the Koine Eirene:

I swear by Zeus, Gaia, Helios, Poseidon and all the gods and goddesses. I will abide by the common peace, and I will neither break the agreement with Philip, nor take up arms on land or sea, harming any of those abiding by the oaths. Nor shall I take any city, or fortress, nor harbour by craft or contrivance, with intent of war against the participants of the war. Nor shall I depose the kingship of Philip or his descendants…142

The oath went on to list all the member states and the ‘peace’ was watched over by a Macedonian garrison positioned on the heights of the Acrocorinth and Chalcis which were described by Polybius as two of the ‘Three Fetters of Greece’ (Demetrias in Thessaly became the third), as well as at the Cadmea, the citadel of Thebes.143 More garrisons would soon appear under Alexander’s regent, Antipater. The real meaning of Greek loyalty, however, was epitomised by Athens’ contribution to the Macedonian-led war effort: the city-state supplied no more than 600 cavalrymen and twenty triremes from a fleet of over 300 in commission.144 So it is no surprise to read that of the fifty-two attested satraps Alexander appointed to govern the newly acquired Persian satrapies, only three were Greek and none of them came from the mainland, a clear sign of continued distrust. Of Alexander’s eighty-four identified hetairoi just nine were Greek, which illustrates the reality of the ‘Panhellenic’ crusade.145 And only thirty-three Greeks were associated with any military command from a list of 834 officers (principally Macedonians) identified in the accounts of Alexander’s decade-long campaign.146

The natural auditorium of the hill of the Pnyx in the foreground and the view across to the Acropolis.

In the first major pitched battle in Asia at the Granicus River in the summer of 334 BCE, the Macedonians slaughtered some 18,000 of perhaps 20,000 ‘warlike and desperate’ Greek mercenaries at the conclusion of the engagement, or so we are led to believe from cross-referencing Arrian’s claims with Plutarch’s. Four Persian satraps and three of Darius’ family also fell. Any Greeks rounded up (Athenians, Thessalians and Thebans) were sent back to hard labour camps in Macedonia. But we should once again be cautious with the numbers, for this has the distant feel of the propaganda of the on-campaign historian Callisthenes, in the form of a lesson to Hellas and the Corinthian League; modern interpretations suggest 5,000 mercenaries might have been killed.147 But Alexander was to have a more effective stranglehold on Greek dissent: he soon controlled the corn supply routes from Egypt and trade through the Hellespont to the Kingdom of Bosphorus and its commercially favourable grain contracts. The Black Sea ports remained the largest grain producer and Greece required ‘more imported corn than any other nation’, a vulnerable state of affairs, as Demosthenes voiced.148

Nevertheless, obtaining the approbation of Athens, Plato’s ‘Hellas of Hellas’, seems to have weighed heavy on Alexander’s mind, or in the mind of those who crafted his public relations machine, for the ethnic divide that separated Macedonians and Greeks persisted through the campaigns.149 When the Great King’s palace at Persepolis burned and ‘prosperity turned to misery’, it was for Athens that revenge was reportedly being extracted.150 In Bactria, Callisthenes had apparently needed to remind his king that it was to the dominion of ‘Hellas’ that Asia was being added (though this may be posthumous Greek spin for it was woven into Callisthenes’ rejection of proskynesis, the prostration before the king that emulated Persian court protocol).151 And in India (‘lands east of the Persian Empire’, much took place in modern Pakistan), Onesicritus claimed Alexander commenced battle with King Porus (a derivative of his Hellenised name) of the Paurava region, broadly the Punjab, with the cry: ‘O Athenians can ye possibly believe what perils I am undergoing to win glory in your eyes.’152

We do sense that Alexander, an honorary Athenian citizen (as Philip had become following the victory at Chaeronea in 338 BCE which brought Greece to its knees), wished to be acknowledged for allowing the city its democratic heart, but he knew in order to do so Athens would need to be hemmed in by pro-Macedonian oligarchs, a situation that left the Pella-salaried Aristotle in a precarious position. It is difficult to say whether Alexander genuinely admired Athens’ constitutional ideals, or whether he shared the jaundiced view of Xenophon and, in particular, the exiled Alcibiades (ca. 450-404 BCE), on its unique governmental system once they became exiles of the state: ‘As for democracy, the men of sense among us knew what it was, and I perhaps as well as any, as I have more cause to complain of it: but there is nothing new to be said of a patent absurdity.’153 Thucydides credited Alcibiades with a speech that extolled the virtues of conquest, and that would have been easier for Alexander to comprehend: ‘We cannot fix the exact point at which our empire shall stop… and we must scheme to extend it’, for ‘if we cease to rule others, we are in danger of being ruled ourselves.’154

No doubt as a part of his education syllabus in the Temple of the Nymphs at Mieza, Aristotle had credited the tight formation of the hoplite phalanx with the forging of a cooperative ethos that made a Greek polis, and so demokratia, possible, and yet his Athenian Constitution detailed its bureaucratic drag: Athens attempted to employ 7,000 jurymen, 1,600 archers, 1,200 knights, 500 council members, 500 arsenal guards, 700 other resident officials with 700 more overseas, 12,500 hoplites (in time of war) and twenty coastal vessels with 2,000 crew; all on an annual income of not much over 1,000 talents once the silver production from the silver mines at Laurium tapered off. Few of the potential new revenue streams suggested in Xenophon’s Poroi (or Peri Prosodon, broadly ‘ways and means’, or ‘revenues’) had ever been introduced. It was in this environment that leiturgia (the root of ‘liturgies’) evolved, requiring the wealthier citizens to assume the funding of onerously expensive public activities in return for an honorific; almost one hundred liturgical appointments existed for festivals alone and these increased under the Diadokhoi. What the constitution failed to mention was the additional cost of a slave ratio of perhaps three to one serving the citizens in Athens.155

Conceivably, with the dichotomies of Aristotle’s Politics fighting in his head, Alexander adopted an erratic policy that turned the cities in his path into an eclectic mix of ‘loyal’ democracies, oligarchies, tyrannies and indefinable in-betweens.156 Philip’s advanced expeditionary force under Parmenio, Attalus and Amyntas had done much the same through 336/335 BCE and some of the alliances they formed were inherited by Alexander, though townsfolk had been sold into slavery by his predecessors too.157 Although Philip’s foray into Asia Minor had found receptive ears in a few Greek cities, others living symbiotically with the Great King’s satraps under the King’s Peace of 387/6 BCE (otherwise known as the Peace of Antalcidas, which had once maintained Spartan supremacy in Greece) just saw trouble ahead.

ISOCRATES’ IDEOLOGICAL INVASION, ALEXANDER’S ARGEAD ADVENTURE

Unlike Xenophon who had his Theban friend, Proxenus, to act as a proxenos and broker relations with Cyrus the Younger, Alexander had received no formal invite to Asia.158 He did, nevertheless, have Isocrates’ famous ‘persuasion through words’. How influential was his early plea for koinonia, a commonality of purpose, remains conjecture, for it had failed to unite Greece against the Macedonian threat. As well as reaching out to Philip II, the Athenian rhetor had courted the fourteen-year-old Macedonian prince through correspondence; Isocrates’ letter praised Alexander’s philanthropos, his philosophos and his philathenaios, the love of Athens.159 The Rhetoric to Alexander, possibly written around 340 BCE by Anaximenes, suggests the prince was indeed a political target in his malleable teens.160 Isocrates had challenged Philip to Heraclean efforts, but his rousing words, more sycophantic than practical on the Pellan-strained budget, might have resonated deeper with the young self-assured Alexander:

Be assured that a glory unsurpassable and worthy of the deeds you have done in the past will be yours when you shall compel the barbarians – all but those who have fought on your side – to be serfs of the Greeks, and when you shall force the king who is now called Great to do whatever you command. For then will naught be left for you except to become a god.161

Xenophon and his working colleague, King Agesilaus of Sparta, had shared Isocrates’ view, though the deep-rooted resentment of Sparta’s supremacy in the wake of the Peloponnesian War made her leadership of any Panhellenic force impossible. Moreover, Sparta had been aided by Cyrus the Younger in the last years of the conflict, a state of affairs that earned the pro-Spartan Xenophon his exile from Athens.162 Since then, military supremacy had passed to Thebes under the remarkable generals Epaminondas, Pelopidas and Pammenes (died 364, 362, 356 BCE respectively), whose military reforms had led victory at Leuctra in 371 BCE over Sparta which was either deliberately excluded by Philip from the League of Corinth, or was standing aloof in a display of xenalasia.163 When Thebes was destroyed by Alexander in 335 BCE, Isocrates’ decades-old call for the invasion of Persia fell upon the new Macedonian hegemon.

When Alexander picked up the challenge, to obtain the funding for the expedition that would extend his rule beyond the bounds the gods and heroes approved of – so Themistocles had warned – he had been forced to borrow some 800 talents and at a loan rate that probably reflected the risk to the capital from (we assume) the Macedonian aristocracy.164 He exempted Macedonians from tax to consolidate his position after Philip’s death and was now dishing out crown lands to secure further funds, though Perdiccas, the future Somatophylax, is famously said to have declined any such security, joining Alexander with a simpler trust in his ‘hopes for the future’.165 Curtius and Arrian claimed the king still carried a debt of 500 talents from his father; this may have been derived from a court source who had wished to reinforce the non-pecuniary notion of loyalty of the state soldiers crossing to Asia, if it was not an allusion to the similar plight of the younger Cyrus in Xenophon’s Anabasis.166

The alleged 60 or 70 talents remaining in the royal coffers at Philip’s death would have covered the wages of the 30,000 or so mixed infantry Alexander crossed to Asia with for only a few meagre weeks without additional plunder coming their way, discounting the far higher remuneration the cavalry would have expected; Duris of Samos (date of birth uncertain, possibly as late the 330s BCE), calculated Alexander had funds sufficient for thirty days and Onesicritus claimed he owed 200 talents besides.167 The 800 newly borrowed talents would have maintained the expedition for no more than a further several months, and, as a result, Alexander was forced to disband his 160-ship navy (costing perhaps 250 talents a month) after the siege of Miletus due to financial constraints; his continued mistrust of his Greek naval officers in the face of 400 Phoenician ships still in Persian employ possibly played a part.168 Although the treasury at Sardis would yield to him and Tarsus would be captured intact (giving him his first mint), and no doubt his adoptive mother, Queen Ada of Caria, made available funds from her stronghold of Alinda, the pressure was on for a confrontation that would prise the Persian treasury open.169

As Alexander pressed on down the coast of Asia Minor, cities and synoecisms that refused immediate obeisance were ransomed, garrisoned, destroyed and pillaged, or occasionally pardoned on the promise of good behaviour. For apart from a few Greek cities on the Aegean seaboard, these were not members of the League of Corinth, and thus they were fair game, despite any ancient Ionian League affiliations.170 Non-Greek communities (those in Lycia, for example) could expect no terms at all; essentially their fate lay in the manner in which they treated the Macedonian advance.

Some cities failed to comply from the outset; others did, and then revolted. More than twenty cities came under siege, and Alexander (if not Philip II before him), and not Demetrius the son of Antigonus, should have earned the epithet Poliorketes, the Beseiger.171 When they did finally fall, Greek, Macedonian or local resident governors were installed (or reinstalled) with nomographoi to draft new laws and ‘correct’ those that had been already been drafted or imposed by the koine sympoliteia, the federal state body that oversaw their interests.172 In Miletus, Alexander was even nominally elected (or self-appointed) as stephanephoros, chief magistrate, for the year 334/333 BCE. There was no Thucydidean Melian Dialogue to weigh up arguments of alignment or neutrality; as Solon (ca. 638-558 BCE) had once been warned: ‘Written laws, are just like spiders’ webs; they hold the weak and delicate in their meshes, but get torn to pieces by the rich and powerful.’173 In fact Solon had himself departed Greece for ten years to avoid being called to task for the decrees that backfired in the wake of his own reforms.174

In the view of Tarn, Alexander’s behaviour was justifiable; he pointed out that the state of affairs in Asia Minor, specifically relating to these years, required extraordinary measures because the outcome of the war with the Great King was still far from certain.175 We have an equally conspicuous apologia by Arrian: Alexander’s ‘… instructions were to overthrow the oligarchies and install democracies throughout, to restore their own local legislation in each city, and to remit the tribute they had been paying to the barbarians.’ This appears to overlook the key objective of the arrangement: the tribute (phoros) was now redirected to the Macedonian regime.176

In truth, all political ideologies suited Alexander’s direction and in isolation each of them worked, for a while. A number of inscriptions preserve the essence of Macedonian machtpolitik and none better than Alexander’s Letter to the Chians, thought to have been written sometime between 334 and 332 BCE. The decree provided for the return of exiles to the island (including the historian Theopompus) with a ‘democratic’ constitution to be reinstated, and yet it demanded that all judicial disputes be referred directly to Alexander. Though Tarn argued this was the ‘decent thing’ to stop the civil strife, Chios, a member of the Corinthian League (as was Lesbos), was forced to donate twenty fully-crewed and funded triremes to the war effort, and the island was summarily garrisoned at its own expense – though the occupiers were termed a ‘defence force’.

To accomplish what he did, and to hold it together with limited military resources, required the threatening charisma and his exploitative genius Alexander had inherited from his father. But it was not a sustainable policy; loyalty was fickle, garrisons were vulnerable to being overrun and so were his regional governors. But it was a salutary lesson on Macedonian-style freedom; the Common Peace was, as Badian noted, an ‘aggressive peace’… ‘governed by the will of one man’.177 And so in Alexander’s Homeric adventure the ‘liberation’ from Persia was to become a very mixed blessing.178

The cynical Diogenes, watching from occupied Corinth, is said to have summed up the campaigning king, his regent then in Athens, and his messenger (named Athlios) who had just arrived in the city, with, ‘athlios par’ athliou di’ athliou pros athlion’. This broadly (and here with poetic licence) translates as ‘wretched son of wretched sire to wretched wight by wretched squire’.179 The mixed signals broadcast by this new order in the Eastern Mediterranean seaboard had to be weighed up against the certainty of annihilation if Alexander’s ambition was stifled.