4

MYTHOI, MUTHODES AND THE BIRTH OF ROMANCE

What are the origins of the Greek Alexander Romance and does the book contain any historical truths relevant to our investigation?

The Greek Alexander Romance is, in one form or another, one of the most influential and widely read books of all time; it has birthed a whole literary genre on the Macedonian king.

Where and when did it first appear and what did it originally look like? Which earlier accounts did it absorb and what is its relationship to the mainstream Alexander histories? Most importantly, does it contain unique factual detail?

We take a closer look at the best-selling book of fables in which Alexander’s testament sits most conspicuously. We review the perennial propensity for writers to ‘romance’ and highlight some of the iconic episodes in history that have been misinterpreted as a result.

‘In their narratives they have shown a contempt for the truth and a preoccupation with vocabulary and style, because they were confidant that, even if they romanced a bit, they would reap the advantages of pleasure they gave to their public, without the accuracy of their research being investigated.’1

Herodian History of the Empire from the Death of Marcus Aurelius

‘… the uncomfortable fact remains that the Alexander Romance provides us, on occasion, with apparently genuine materials found nowhere else, while our better-authenticated sources, per contra, are all too often riddled with bias, propaganda, rhetorical special pleading or patent falsification and suppression of evidence.’2

Peter Green Alexander of Macedon

‘Historical, or natural, truth has been perverted into fable by ignorance, imagination, flattery or stupidity.’3

Sir William Jones On the Gods of Hellas, Italy and India

In 1896 the historian and orientalist, Sir Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis Budge, proposed only one country could be the birthplace of Alexander’s story, and that country was Egypt.4 Its new city, ‘Alexandria-by-Egypt’, as the Greeks came to differentiate it from the conqueror’s many eponymous settlements, was to become a centre for syncretistic literature and the likely birthplace of the Corpus Hermeticum, the Sibylline Oracles, The Wisdom of Solomon, the Septuagint with its reputed seventy-plus translators, and its Alexandrian Canon too. Much of the detail that eventually filled the Suda most likely had its origins in the vibrant metropolis whose creative environment recycled apocrypha onto papyrus in the Hellenistic Age. And we have grounds to believe one of its earliest and most successful productions was to metamorphosise into the Greek Alexander Romance.5

As antiquities adviser to the British Museum, Budge was exploring the origins of the various Ethiopic Romance recensions, and he stumbled on something of a basic truth: the nations humbled by Alexander, he reasoned, would not so quickly record their own downfall.6 Only one place immediately prospered in the aftermath of the Macedonian campaigns, and that was Egypt. The propitious interpretation of Alexander’s seer, Aristander, which deflected embarrassment at Alexandria’s mapping-out when birds flocked to eat the barley-meal being used as the boundary marker, had provided a founding prophecy: the new city, which bears the inscription ktistes, founder, against Alexander’s name in the Romance, would feed the world.7

Cleomenes’ posthumous bank balance of some 8,000 talents, a legacy of over-zealous and quasi-autonomous tax collection, probably had the greater part to play, though its fate was now underpinned by the talisman that was Alexander’s body.8 Egypt’s new heart, Alexandria, established by the harbour settlement of Rhacotis, originally established to fend off Greek pirate attacks on the Nile Delta, was becoming something of a ‘new Heraclion’; it was fostered into maturity by the Bodyguard, Ptolemy I Soter, who, within two decades of taking up his post, would proclaim himself a king.9

ALEXANDER THE TWO-HORNED BEAST

Macaulay proposed history ‘is under the jurisdiction of two hostile powers: the Reason and the Imagination’, and, he added, never equally shared between them.10 This was particularly the case in ancient Attic Greek where the stories of the past were literally mythoi, and the segregation between myth, legend, and the factual past was a soft border blurred by Homeric epics and Hesiod’s Theogonia, which permitted a coeval interaction between men, heroes, and gods. Scholars have even pondered that ‘the absence of a clear distinction between factual and fictional discourse’ in the influential dialogues of Plato, ‘far from being idiosyncratic, may reflect a larger feature of Greek (or ancient) thinking’.11 Even Thucydides, who claimed to have sacrificed ‘entertainment value’ (hedone) in order to dispense with to muthodes, the mythical elements in his work, nonetheless interlaced his texts with self-constructed speeches which reintroduced just that.12 But the results were ‘immortal’ and the legends live on; as the habitually terse Sallust (ca. 86-35 BCE) reasoned, ‘these things never were, but are always’.13

We will illustrate how fraud entwined itself around the most momentous of historical episodes, but once a deliberate deceit is discovered, the truth is more often than not revealed. When an episode is adorned in the colourful robes of romance, however, we are on less firm ground, for truth and fiction may have been wedded in a ceremony that rendered them lifelong partners: ‘There are many occasions in the story of Alexander when it is hard to be sure just where history ends and romance begins.’14 To quote Michael Wood on the problem: ‘We are accustomed to believing that fiction can tell both truths and untruths… poets have a (highly visible) stake in the notion, but so do historians and philosophers and scientists.’ In which case it is ‘… misleading to contrast the so-called “historical biographies” with the legendary lives.’15 And this better equips us to appreciate how the Pamphlet and Alexander’s Will, along with many other genuine campaign episodes, came to be bedfellows with the Greek Alexander Romance.

Separating the historical from the fabulae has indeed proved no easy task, for material was added through a gradual process of accretion. Analysis of the Romance manuscripts was made easier once the composite 1846 editio princeps of Müller had been printed in Paris, for it provided a continuous non-lacunose text.16 Adolf Ausfeld’s 1894 Zur Kritik des Griechischen Alexanderromans and his treatise of 1901, with that of Kroll in 1907, attempted to reconstruct the lost Romance archetype and started probing into the mysteries behind ‘peculiarities’ within the main narrative and the testament of Alexander sitting in its last chapter. Merkelbach’s 1954 study, Die Quellen des Griechischen Alexanderromans, articulated the challenge of detecting the underlying sources, and alongside them developed an influential corpus of German studies that set the forensic standard for a modern reassessment of what we might term the ‘quasi-historical’ Macedonian king.17

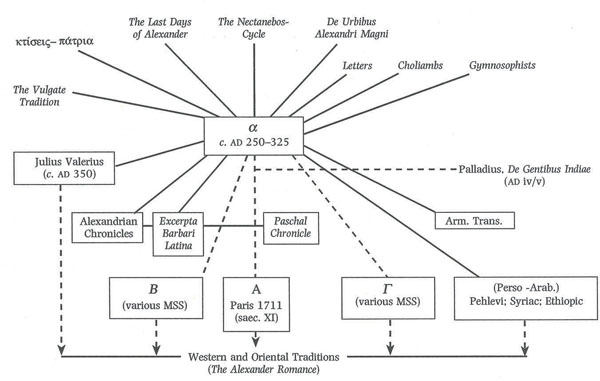

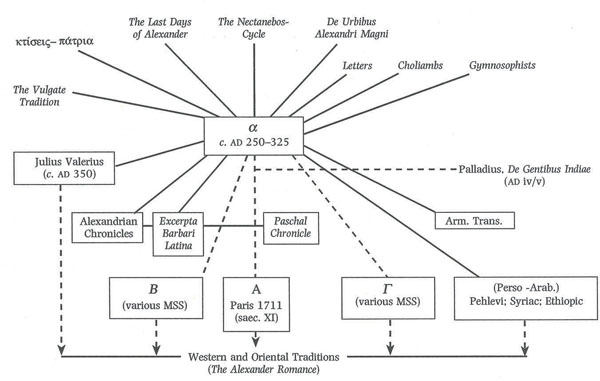

Attributing the Romance in its earliest form to a single author or date remains impossible, but evidence suggests that both the unhistorical and the quasi-historical elements were in circulation in the century following Alexander’s death. The oldest text we know of today, recension ‘A’, is preserved in the 11th century Greek manuscript known as Parisinus 1711; the text is titled The Life of Alexander of Macedon and ‘this most closely resembles a conventional historical work’, though any factual narrative is only a ‘flimsy continuum’ to which other elements were attached. Recension A, whilst ‘ill-written, lacunose, and interpolated’, is nevertheless the best staging point scholars have when attempting to recreate an original (usually referred to as ‘α’ – alpha) dating back some 700 or 800 years (or more) before the extant recension A.18 We cannot discount an archetype that may have been written even earlier still, in the Ptolemaic era; if Callisthenes was once credited with its authorship (thus ‘Pseudo-Callisthenes’), the prevailing belief must have been that it emerged in, or soon after, the campaigns. Through the centuries that followed, the Romance evolved and diversified into a mythopoeic family tree whose branches foliaged with the leaves of many languages, faiths and cultures; more than eighty versions appeared in twenty-four languages.19

The Alexander Romance stemma from recension ‘α’, which may itself be an embellished descendent of an earlier archetype. Provided with the kind permission of Oxford University Press and copied from PM Fraser Cities of Alexander the Great, Clarendon Press (1996).

The Hellenistic world saw exotic tales arriving from the fabled lands of Kush to the south of Egypt and from the distant East, carried down the Silk Road with the help of the settlements Alexander had founded or simply renamed along its route. According to Strabo, who studied in Egyptian Alexandria, the ‘city’ of Alexandria Eschate (‘the furthest’) in the Fergana Valley had brought the Greek settlers and the Graeco-Bactrian Kingdom into contact with the silk traders of the Han dynasty of the Seres (the Chinese, who lived to age 300, claimed Pseudo-Lucian) as early as the 3rd century BCE.20 Within 200 years the Romans would have a voracious appetite for silk and they obtained cloth through the Parthians who most likely encouraged the belief that silk grew on (or as) trees.21 Pliny dispelled that myth and described the role of the silkworm, and yet the Senate issued edicts in vain to prohibit the wearing of silk due to the trade imbalance it caused; one decree was based on accusations of immodesty for the way silk clung to the female form. In Pliny’s reckoning, India, China and the Arabian Peninsula extracted ‘from our empire 100 million sesterces per year – that is the sum which our luxuries and our women cost us…’22

Ptolemaic Egypt had fostered trade eastward as far as India with the help of Arabs and Nabateans, and the resulting contact fertilised Hellenistic literature. But, paradoxically, much of the geographical knowledge of the former Persian East was lost in the period between Megasthenes’ eyewitness reports from India in the generation after Alexander (ca. 290s BCE) and the Parthian Staging Posts of Isidore of Charax in the 1st century CE, principally due to the collapse of the Seleucid Empire and its dynasty established by Alexander’s former Bodyguard, Seleucus.23

It was a millennium later that Marco Polo’s twenty-four-year adventure and travelogue opened up knowledge of the East once more. His account appeared under a number of titles including Livre des Merveilles du Monde, The Book of the Marvels of the World, first published in the descendant of Old French (langues d’oïl), and Il Milione written in Italian, which brought back stories of Cathay and Kublai Khan, lending further colour to developing European fables. The authorship of what we have come to name The Travels of Marco Polo is, in fact, contested, as is its original transcribed language; tradition holds that Polo dictated the book to a romance writer, Rustichello da Pisa, while in prison in Genoa between 1298 and 1299, and we would assume in Italian. Rustichello had already written a work in French, Roman de Roi Artus (Romance of King Arthur), and certainly much interpolated material was included, so we might speculate how much of Polo’s original detail remained unsullied in the hands of an established story-philanderer. The oldest manuscripts differ widely in content and length, and what we read today has been ‘standardised’ like other romances and the Iliad.

The Greek Alexander Romance was similarly developed. As examples of the genre offspring we have the Latin Epitome of Julius Valerius (probably 4th century) and the Historia de Preliis Alexandri Magni (The Wars of Alexander the Great) of Archpriest Leo of Naples (10th century), first put to print in 1487 and giving rise to a whole new generation of re-renderings of the story. With over 200 surviving manuscripts, the Historia de Preliis drew much inspiration from Curtius’ history of Alexander, as did the Alexandreis siva Gesta Alexandri Magni, a Latin poem in epic-style dactylic hexameter by the theologian Gautier de Chatillon (ca. 1135-post 1181), with a similar Curtian ten-book layout and much credit paid to the goddess Fortuna.24 The verses were so popular that they displaced the reading of ancient poets in grammar schools.25 De Chatillon’s production, ‘a tissue of other texts’ (Virgil, Lucan, Ovid, Horace and Claudian among them), could not avoid alluding to the recent death of Thomas Beckett (1170) and the failures of the first Crusades; it even housed the crucifixion of Jesus some three and a half centuries out of context.26 De Chatillon was fluid with his metre, ranging back and forth between dactylic hexameters, iambics and trochaics; fortunately these provided a stylistic rhythm that identified much of the imported syncretism.27

The Alexandreis had other siblings and more distant relatives too: the distinctive Li romans d’Alixandre, for example, fed by the ‘alexandrine’ verses of Lambert de Tort, and the Mort Alixandre credited to Alexandre de Bernay, alongside the Roman d’Alexandre by Albéric de Pisançon which was the possible source of the German Alexanderlied (ca. 1130) of Lamprecht ‘The Priest’.28 These were hugely influential in the Middle Ages and they were amongst the earliest texts translated into the vernacular literature that emerged in the Renaissance. Like the oil paintings of the period, they were cultural palimpsests, absorbing textual supplements and stylistic elements from other classical works as well as the iconography of their day. The Alexandreis has the Macedonian king and his men fighting in chainmail with axes and broadswords against Arabs who fled in terror, scenes more representative of crusaders than ancient Greek hoplites; we additionally read of Spanish, Teutonic, Gallic and Flemish envoys arriving at Babylon to pay homage to the Macedonian king.29 If Tarn’s criticism of ‘invented embassies’ is indeed correct, then every age wished to communicate with the Macedonian ruler of the Graeco-Persian world.30

The Saracen threat from the Ottoman Empire loomed large in the minds of the romance writers, and it led to the emergence of vivid characters born out of fear or misplaced hope. In 1165 the Letters of Prester John entered circulation; this was an epistolary fantasy that convinced Pope Alexander III of the existence of a lost Nestorian Christian kingdom somewhere in central Asia.31 The character’s provenance might be found in the Historia Ecclesiastica of Eusebius (ca. 260-340 CE), the Bishop of Caesarea, and the fabled Prester John and his Christian outpost was an alluring enough idea for the Portuguese to venture to Ethiopia in search of his kingdom.32 He, and the appropriately named legendary Gates of Alexander, were supposedly constructed to hold back the pagan hordes, imagery with direct parallels in the Arabic Qur’an. The gated wall at the world’s end was in fact the narrow geographical feature that formed the Caspian Gates.

Josephus may have played a part in the legend, for in his Jewish Wars he claimed Alexander had indeed blocked the pass with huge iron gates.33 That is somewhat ironic as Josephus had expounded: ‘It is often said that the Greeks were the first people to deal with the events of the past in anything like a scientific manner… but it is clear that history has been far better preserved by the so-called barbarians.’34 He added: ‘Nevertheless, we must let those who have no regard for the truth write as they choose, for that is what they seem to delight in.’35 But the fantasy was seductive and ‘breaking the bolts’ or the ‘gates’ of the earth had been a popular Roman locus (Greek, topos) when Alexander was under the knife.36

A map titled A Description of The Empire of Prester John, Also Known as the Abyssinian Empire. Produced in Antwerp in the 1570s by Abraham Ortelius, it outlined Prester John’s fabled empire with both real and imagined names. Ortelius’ Theatrum Orbis Terrarum is regarded as the first atlas and was the most expensive book ever printed. Nevertheless, some 7,300 copies were printed in four editions from 1570 to 1612.

At the height of the Crusades it was alleged that John, the supposed Presbyter of Syria, had re-taken the city of Ecbatana.37 Yet much of Middle Age literature was about historical alchemy and Prester John was just one base metal alloyed with the superstitions and apprehensions of the age. But for an influential time he was as real as Alexander had been in the minds of his chroniclers and he became a regular feature in medieval texts. His legend was finally laid to rest when his mythical kingdom was removed from maps by the German Orientalist Hiob Ludolf (1624-1704) who exposed the seductive fancy for what it was.

Today in Greece the best-known Romance derivative is the He Phyllada tou Megalexantrou, first published in Venice in 1670 and never out of print through the three centuries that followed. The text represented the first attempt to ‘fix’ the fluid Romance recensions in circulation. Emerging ‘from the Byzantine preoccupation with the classical past’, the conflicts between the former Eastern Roman Empire and Ottoman Turks were inevitably dragged into the story.38 The Phyllada portrayed Alexander as the protector of Greek Orthodox Christian culture, and ultimately as kosmokrator, the ruler of the world.

Through the romance genre Alexander’s story finally infiltrated the East in a more permanent way than his own military conquest managed to. He entered the Qur’an texts, reemerging as Dhul-Qarnayn, the ‘two-horned’ who once again raised unbreachable gates to enclose the evil kingdoms of Yâgûg and Mâgûg (Gog and Magog) at the world’s end; the reincarnation, with roots in the Syriac version of the Romance, had its earlier origins in the silver tetradrachms issued by Alexander’s successors that depicted him with rams’ horns. A Persian Romance variant was the Iskandernameh and alongside it Armenian and Ethiopian translations circulated imbuing the tale with their own cultural identities. An interesting textual ‘rediscovery’ appeared in the 8th century Syriac Secretum Secretorum; it included what was purported to be Aristotle’s lost doctrine on kingship dedicated to Alexander.39

Ironically, it was not a Greek book, but the Lives of the Physicians (1245/46) by Ibn Abi Usaib’a (ca. 1203-1270), that preserved much of Aristotle’s biographical detail, and yet it hardly merits a mention in debates on Peripatetic scholarship. Neither does the Kitab al-Fehrest of Ibn al-Nadim (died ca. 998 CE), a remarkable compendium of pre-Islamic text he himself described as ‘an index of all books of all nations’.40 Where Western texts vanished with the fall of Rome and with the torching of private collections and libraries at Pergamum and Alexandria, ‘… most of the surviving Greek literature was translated into Arabic by 750 CE; Aristotle became so widely studied that literally hundreds of books were written about him by Arabic scholars.’ Even his Will survived intact in the writing of An-Nadim, Al-Qifti and Usaib’a.41 The Muqaddimah of Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406), a universal history rich in new political, economic and historiographical theory, much of it again influenced by Aristotle’s ideas, only reappeared in the West in the 19th century, as the Prolegomena. Trade with the Muslim world had flourished through Constantinople, but the voices of these authors are rarely heard west of the Hellespont; ‘East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet.’42 There was however one exception to this cultural irreconcilability: Alexander himself, a historic genre not as separable from romance as we might imagine.

Many parallels to the Alexander romance corpus have appeared in literature: the rabbinic aggadah for example, with its folklore, historical anecdotes and moral exhortations dressed like biblical parables with attendant mythical creatures. We have the Norse Sagas which recapture a similar legendary past, and Beowulf, the Anglo-Saxon poem (ca. 1,000) of Scandinavian pagan legends and heroic exploits that emerged at the end of the Dark Ages when barbarism still triumphed over classical civilisation.43 However, the enduring tale of King Arthur has the most significance for us, and somewhat predictably, Alexander and Arthur crossed paths in the 14th century French romance, Perceforest. Stock to Greek playwrights was the storm at sea, a neat mechanism for a dramatic location shift and one reused, for example, effectively in Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Perceforest upheld the tradition, and Alexander was swept off course to a mythical visit to Britain.44

Transformed by Malory into Morte D’Arthur (ca. 1470), the Arthurian canon dominated British historiography for centuries. The ancient sources behind the legends of Brut, Arthur and his knights, have disappeared, leaving us in the dark on their identities, real or imagined.45 Malory penned the Arthurian romance based on the earlier account of Geoffrey de Monmouth, whose Historia Regum Britanniae (ca. 1135) and Chrétien de Troyes’ French ‘grail’ romances, appeared in the mid-12th century. The debate on Monmouth’s work goes on regarding the extent to which it was purportedly derived from early Welsh or Breton manuscripts of an Archdeacon Walter. As early as 1190 the historian William of Newburgh declared of Monmouth’s work, which traced the lineage of English kings back to Troy, ‘… only a person ignorant of ancient history would have any doubt about how shamelessly and impudently he lies in almost everything…’ He followed with:

… it is quite clear that everything this man wrote about Arthur and his successors… was made up, partly by himself and partly by others, either from an inordinate love of lying, or for the sake of pleasing the Britons.46

Any truth behind the identity of Arthur is lost and his very existence is questioned. Yet so was the existence of Troy until Heinrich Schliemann claimed to have dug it up in 1873 in his search for King Priam’s treasure. Whether part of Mycenaen legend, or steeped in historical fact, Troy still faces the same hurdle as Plato’s (or Solon’s) Atlantis, Arthur’s Camelot and the once-ridiculed 4th century BCE journey by the explorer Pytheas to Thule.47 In the case of the ‘biblical-only’ Hittites, we were ignorant of the existence of a once-great empire for three millennia until Hattusa, the capital, was stumbled upon in 1834 and yet it defied identification for almost another century until detailed tablets were finally translated.48 If the Vandals, Visigoths, Franks or Huns and the later Arabic invasions had between them managed to destroy every library in Europe, leaving Wallis Budge and the British Museum only with exotic Ethiopian Romance redactions, would we be able to say with any certainty that Alexander had really existed?

To some extent, Rome participated in the rise of both the romances of Arthur and Alexander: the fall of the Roman Empire, which saw the loss of the libraries that guarded primary historical testimony, allowed for a further metamorphosis in Alexander’s story, and Rome’s abandonment of Britain set the scene for Arthur’s legend to emerge. For when sheep began to graze in Rome’s Field of Mars, European history entered a millennium that put more stock in colourful fables than the accounts of, for example, the pedantic and stoic Arrian, whose Anabasis fell out of circulation until the Renaissance as a result. The change in biographical slant was not sudden and character portrayals were remodelled over time: compare the no-nonsense Sallust with Plutarch’s didactic profiling a century on, then place them beside the biographies of the Scriptores Historiae Augustae penned perhaps a further two centuries later.49

These controversial texts, first termed Scriptores Historiae Augustae by Isaac Casaubon (1559-1614), are a remarkable collection of source-rich documents of ‘dying Paganism’. In this self-labelled mythistoricis, the biography of Alexander Severus (ruled 222-235 CE) is an ‘awkward imitation’ of the Cyropaedia, according to Edward Gibbon.50 It is appropriate, then, that the Latin romanice scribere – to write in a ‘romance language’ – formed the origins of ‘romance’.51 These biographies were supposed to pick up where Suetonius’ Lives of The Twelve Caesars ended, a logical claim if ever the biographies of Nerva (emperor 96-98 CE) and Trajan (emperor 98-117) are found. The compendium, like the equally vexatious and still anonymous two sections (of three) of the Origo gentis Romanae, provides unique biographical details of late emperors (spanning 117-284 CE) presented as a corpus of texts by six historians written during the reigns of Diocletian (ca. 245-311 CE), the emperor who managed to push the barbarians back over Rome’s borders, and Constantine (272-337 CE).52

Possibly the works of a single ‘rogue scholiast’, the authenticity and accuracy of the Scriptores Historiae Augustae are hotly debated, but it remains the sole account of a period when little other information exists. Debate on its dating and origins continues, and though the compilation is lucid at times, with some 130 supporting documents cited as the ‘evidence’, the web of home-spun sources descends into fable and rhetorical flights of fancy, heading in the direction of full-blown romance.53 Nevertheless, the Scriptores were used as a source in Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (published 1776-1789), a treatise not short on irony (and a little plagiarism), and which concluded that the social process underpinning the title had been ‘… the greatest, perhaps, and most awful scene in the history of mankind.’ Gibbon’s research method was initially widely praised for he opened with:

I have always endeavoured to draw from the fountain-head; that my curiosity, as well as a sense of duty, has always urged me to study the originals; and that, if they have sometimes eluded my search, I have carefully marked the secondary evidence, on whose faith a passage or a fact were reduced to depend.54

Momigliano was scathing of the impression Gibbon attempted to perpetuate about his methodology and his pedantic footnotes, summing up his use of the Scriptores with: ‘Theirs was an age of forgeries, interpolations, false attributions, tendentious interpretations. It would be surprising if the Historia Augusta should turn out to be more honest than the literary standards of the time required.’55 Yet is it just another example of where ‘romance’ had clearly infiltrated ‘history’ with a dividing line we cannot readily see today.

EUHEMERISING THE TESTAMENT

In attempting to extract Alexander’s Will from his Romance we are in fact taking a euhemeristic stance: treating what has been deemed mythical as an echo of historical reality. This is an appropriate moment to introduce Sir Isaac Newton into our contemplations, for his tendentious views as a deeply religious euhemerist could not be easily revealed in his lifetime, and neither could the twenty years he dedicated to heretical alchemy in his search for the Philosopher’s Stone. Newton’s Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended was posthumously published in 1728; it was an exegesis in which he employed his mathematical erudition to recalibrate the events of antiquity to bring them ‘safely’ into the chronology proposed by Archbishop James Ussher. It may have inspired the publication of the multi-authored The Universal History from the Earliest Account of Time to the Present, which also ‘found’, or forged, ‘correlations between the Bible and classical worlds’.56

Newton’s book dated the Creation to 4004 BCE, following which he placed Noah’s flood in 2347 BCE and shifted the fall of Troy from an Eratosthenes-supported date of 1183/4 forward to ca. 904 BCE, arguing that even the most ancient of extra-biblical historical references were post-1125 BCE.57 His euhemerist hermeneutics (here meaning the study of the interpretation of ancient biblical texts) positioned all gods and heroes as factual kings, and he too viewed myths as historically inspired;58 in the process Newton credited atomic theory to one Mochus the Phoenician whom he supposed was the biblical Moses. Newton modestly summed up his introduction with: ‘I do not pretend to be exact to a year: there may be errors of five or ten years, and sometimes twenty, and not much above.’

The full title of Newton’s publication included the prefix, A Short Chronicle from the First Memory of Things in Europe, to the Conquest of Persia by Alexander the Great. It was presented with a covering letter to the Queen from John Conduitt who claimed ‘Antiquity’ had benefited from ‘… a sagacity and penetration peculiar to the great Author, dispelling that Mist, with which fable and error had darkened it.’ Newton’s treatise, consciously or otherwise, supported the methodology of the 1623 On the Plan and Method of Reading Histories by Digory Whear, and ironically so, for Newton is better remembered for the weighty gravitas of his Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, whose publication was delayed when poor sales of the History of Fishes almost bankrupted the Royal Society.59

Newton’s gravitational masterpiece was based on Kepler’s astronomically unpopular law of planetary motion, and that too is ironic, for Kepler, who held the conviction that God had a geometric plan for the universe, fell foul of the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, as did the texts of Galileo with whom he collaborated. Although Kepler’s first publication, the Mysterium Cosmographicum, attempted to reconcile a heliocentric solar-system with biblical geocentrism, his refusal to convert to Catholicism (and dispense with elliptical orbits) ultimately sealed his fate, despite his imperial patronage in Prague. He was banished from Graz where his last astronomical calendar was publicly burned, and his mother was accused of witchcraft, an allegation backed up by spurious claims that his Somnium, the first attempt at ‘science fiction’, had referred to demonic themes. In 1626 the Catholic Counter-Reformation placed his library under lock and key.60 In Newton’s case, as one author has commented in his study of his lesser-known euhemerist life, ‘the hunter turned prey’ when his scientific discipline produced more myths than it dispelled.61

While we are on the matter of euhemerism, it looks wholly suspicious that it was Cassander, the regent’s son accused of ferrying to Babylon the poison bound for Alexander, who employed Euhemerus, the founding ‘mythographer’, at his Macedonian court.62 One result was Euhemerus’ utopian land of Panchaea (surely Platonist in origin), though his employer, Cassander, displayed few of the qualities found on the idealised Indian Ocean island paradise.63 Could Euhemerus have been tasked with attempting an ironical role-reversal: that of explaining away a damaging ‘truth’ – Cassander’s part in the alleged plot – as nothing more than a myth propagated by a scurrilous pamphleteer? Euhemerus’ principal work was his Sacred History.64 So was it perhaps he, without the reverence his title suggested, who tossed the Pamphlet Will and conspiracy into the final chapter of an early redaction of the Greek Alexander Romance?

Many euhemeristically inclined historians accept that romances may be built around a folklore that preserved elements of genuine historicity, a stance Ennius found useful when linking Rome’s foundations to Troy.65 Others more cautiously see myths as ‘symbols of permanent philosophical truths’, and the Greek legends as natural cyclical processes forever recurring.66 If an echo of reality has indeed been captured, these lodestones may still be camouflaged by the incredible. It’s worth re-quoting Peter Green’s conclusion on the issue, though he never linked his observation to Alexander’s Will:

… the uncomfortable fact remains that the Alexander Romance provides us, on occasion, with apparently genuine materials found nowhere else, while our better-authenticated sources, per contra, are all too often riddled with bias, propaganda, rhetorical special pleading or patent falsification and suppression of evidence.67

Other ‘legends’ may have similarly been built around misplaced or forgotten events. Jason’s journey in the Argo and the legend of King Solomon’s Mines may all be aggregates of real journeys distilled from explorers’ travel logs along exotic trading routes; the latter inland to the metropolis of Manyikeni in the land of the city of ‘Great Zimbabwe’ through the port of Kilwa in modern Tanzania – termed the finest and most handsomely built towns by Ibn Battuta (1364-ca. 1369) – its name already changed to ‘Quiloa’ (as the Portuguese called it) by Milton in Paradise Lost. Solomon’s legendary mines were perhaps in the lost Land of Punt, ‘Ta netjer’ (‘God’s land’), believed by the people of Egypt to be their ancient homeland. According to biblical references, Phoenician ships traded down the African coast, visiting Ophir at the end of the Red Sea and bringing back ‘gold and silver, ivory, and apes and peacocks’ for Solomon; it was a famed trading city of ‘stones of gold’ that has been variously linked to Great Zimbabwe, Sofala in Mozambique (in Milton’s Paradise Lost) and Dhofar in Oman.68

Under Ptolemy II Philadelphos, in the generation immediately after Alexander, Greek influence extended to Elephantine, an island in the Upper Nile that marked the boundary with Ethiopia (in Greek: ‘the land of men with burnt faces’), though the Satrap Stele erected in 311 BCE appears to reference an earlier Nubian campaign of 312 BCE under Ptolemy I Soter who may have stationed garrisons at Syene (Aswan). Elephantine (the Greek name for Pharaonic Abu at Aswan), previously used by Alexander as a deportation centre, was perhaps an early centre of the ivory trade when Ptolemaic commerce started to penetrate the African interior; Herodotus had apparently visited the trading post ca. 430 BCE. Commercial ties with the kingdom of Kush with its capital at Meroe (in today’s Sudan) had flourished after Persian expeditions attempted to subdue it, and references to its Nubian ruler, Queen Candace, and to its regional wealth appeared in biblical references.69

A curiosity with the source of the Nile and reason for its annual flooding was a common investigative and well established theme in Greek scholarship since the time of Herodotus, and it reappeared in Aristotle’s now lost treatise, De Inundatione Nili (as titled in a medieval Latin translation); he finally pinned the phenomenon on the Ethiopian summer rains, as Democritus, Thrasyalces and Eudoxus of Cnidus had proposed before him.70 Aristobulus apparently touched on the problem too, and a tradition even existed in Roman times (through Seneca’s description and Diodorus’ polemic on the issue, for example) that Callisthenes claimed Alexander had commissioned an expedition to Ethiopia to ascertain the truth. If so, it could explain the reported presence of Ethiopian ambassadors in Babylon.71

State-employed elephant hunters would disappear into the African interior for months at a time once the Seleucids cut the Ptolemies off from their supply of Indian war elephants; they would return with animals never before seen and which became ‘objects of amazement’. There were reports of snakes 100 cubits long (approximately 150 feet) large enough to devour bulls and oxen and even bring elephants down.72 A live 30-cubit-long python was delivered to Ptolemy II Philadelphos, according to Diodorus, and once exhibited it became a court showpiece.73 To quote Bevan’s 1927 summation of the second Ptolemy:

He was a parallel to Solomon in his wealth, surpassing that of any other king of his time… Perhaps it was less the real Solomon to whom Ptolemy II was a parallel than the ideal Solomon portrayed in the Book of Ecclesiastes – the book written by some world-weary Jew at a date not far off from Ptolemy’s time. Ptolemy, too, was a king who had ‘gathered silver and gold and the peculiar treasure of kings and of provinces’, who got him ‘men-singers and women-singers, and the delights of the sons of men, as musical instruments, and that of all sorts’, who had ‘proved his heart with mirth and enjoyed pleasure’, who had ‘made great works and builded him houses’…74

This approaches the fabled tones of Polo’s description of Shangdu (Xanadu) and the summer court of Kublai Khan that was immortalised in poetry by Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Although Solomon existed historically, two millennia hence, will history be able to differentiate between Rider Haggard’s Allan Quatermain and his real-life model, the British explorer and hunter, Frederick Courtney Selous – who ‘led a singularly adventurous and fascinating life, with just the right alternations between the wilderness and civilisation’ – in the fictional search for Solomon’s mines?75

THE MUTHODES OF MIEZA AND PROPAGANDA OF PELLA

Chimeral characters frequent the most influential of ‘historical’ episodes, and nowhere more vividly than when early classical Greece emerged from its Dark Age.76 In the Iliad the 1,186 troop transporters comprising the Greek flotilla to Troy (the Catalogue of Ships; a number frowned upon by Thucydides) may in fact represent a hundred late Bronze Age and Mycenae-led invasions across the Aegean; it was the start of an ongoing saga continued in the Aethiopis, Ilias Mikra (Little Illiad), the lost Iliou Persis, The Sack of Ilium, Nostoi, Odyssey and the Telegony which completed the Epic Cycle.77 Hittite texts suggest the invading Ahhiyawa (linguistic links to the Akhaioi, the Achaeans, are hard to dismiss) may have been Mycenaen Greeks based in coastal Asia Minor who were fighting for control of Wilusa, likely the Hittite name for Troy.78

A photo of Wilhelm Dörpfeld and Heinrich Schliemann at the Lion Gate of Mycenae ca. 1884/5.

Some of the underlying imagery, if not its application, is sound. There is much evidence, for example, that the legend of the Wooden Horse of Troy started life as an Assyrian-style battering ram, for many were ornately horse-headed in design and fully enclosed to house and protect the men who inched them forward to the walls.79 On the other hand, the now lost On Rhetoric According to Homer by Telephus of Pergamum exposed the narratives within the Trojan epics for what they really were: flights of epideictic fancy that reinforced the dominant value systems underlying the tale: the aidos and the nemesis that framed honour and revenge.

Whether there ever was a ‘Homer’ is doubtful, whether blind as one tradition claimed, or indeed far-sighted and as many as seven cities staked their claims as his home: Cyme, Smyrna, Chios, Colophon, Pylos, Argos, and Athens.80 In one view, ‘the works ascribed to Moses and Homer were libraries’, and ‘to deprive a library of an author would be to consign it to the realm of the anonymous’;81 ‘Homer was a sort of shorthand for the whole body of archaic hexameter poetry.’82 As with the thirty-three poems comprising the Homeric Hymns, a collection of different authors from many periods coalesced into something approximating a genre; the epics were collected into a ‘book’ sung by the Homeridai, the guild of the ‘sons of Homer’ that kept the ancient accounts alive orally at the Panathenaia.83 Certainly the Life of Homer (one of many ‘lives’) by a Pseudo-Herodotus betrays the fictional traits of a later age.84 The still anonymous Greek Anthology proposed more divine origins: ‘Whose pages recorded the Trojan War and of the long wanderings of the son of Laertes? I cannot be sure of his name or his city. Heavenly Zeus, is Homer getting the glory for your own poetry?’85

The Roman poet Horace (65-68 BCE) coined the term ‘Homeric Nod’ in his Ars Poetica to describe the continuity errors Homer repeatedly made through the Iliad, and this perhaps supports the ‘multiple-author’ theory over a single compiler of the epic of prehistory.86 Today the corpus of literature contained in the Homeric or Trojan Epic Cycle, or rather in its scholia, the critical and explanatory commentary in the margins, has spurred its own investigative science: Neoanalysis.87

A gypsum wall panel relief from the palace of Tiglath-Pileser III (reigned ca. 744-727 BCE) at Nimrud dating to ca. 730 BCE, showing an Assyrian battering ram in front of the walls of a city under siege. The fully enclosed and wheeled battering ram may be the inspiration for the legend of the Trojan Horse. The panel is now in the British Museum. BM 118903.

Herodotus’ semi-mythical battle between the champions of Sparta and Argos in the mid-6th century BCE at Thyrea described a single sun-baked blood-soaked day which might in fact have similarly recalled many campaigning seasons that witnessed similar hoplite clashes on the plains of Lacedaemonia in the heart of ‘the dancing floor of Ares.’88 Reminiscent of a gladiatorial arena, the format at Thyrea, designed to limit casualties, allocated victory to the last man standing, in this case a lone Spartan who committed suicide for fear that his valour would be questioned in the face of the deaths of all his comrades. But the outcome of the battle reads more like a tutorial on the prevailing warrior honour code. Some 300 in number from each city, the Thyrean champions are reminiscent of the elite Hieros lochos, the Theban Sacred Band, the shock troop corps of paired lovers that Alexander annihilated in 338 BCE, and whose remains were likely discovered in the 19th century.89

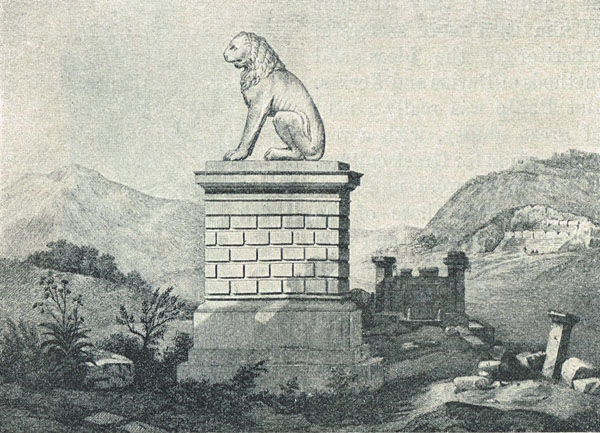

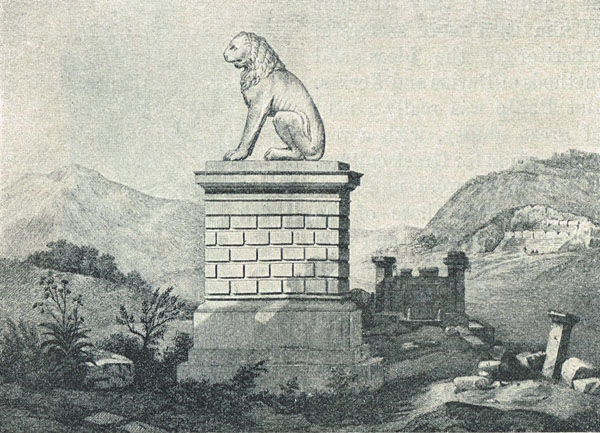

The battle at Chaeronea remains well attested, as does Philip’s harsh treatment of Boeotian soldiers who left their crack unit isolated: Boeotian corpses had to be purchased by their relatives, and captives were ransomed or sold into slavery. But was the Theban Sacred Band, a unit modelled on Spartan example, really annihilated to the last man as texts record, as a total of 254 skeletons were excavated from the tomb guarded by the Lion of Chaeronea? ‘Perish any man who suspects that these men either did or suffered anything that was base’, exclaimed Philip II upon seeing their corpses after the battle.90 Perhaps the more poignant testament to their bravery is a tumulus 230 feet around and some 23 feet high that bears witness to the polyandreion, the mass grave, of their Macedonian attackers who were inhumed with their weapons.

The 20-foot tall Lion of Chaeronea as it appeared ca. 1907 in Outlines of European History, after earlier repairs and reconstruction of the fragments in 1902. According to Pausanias, the original statue was erected to guard the graves of the Theban Sacred Band who fell at the battle in Boeotia between Mt Helicon and Mt Parnassus. There is no surviving inscription. Excavation of the quadrangular enclosure revealed the remains of 254 corpses laid out in seven rows. Similar statues and a communal tomb (polyandreion) have been found at Thespiae and Amphipolis.91

But monuments to valour date further back. The battle at Marathon in 490 BCE clearly epitomised Greek arete and aidos, the classical codes of valour and duty. However it was likely Thersippus, or more popularly Eucles, and not the hemerodrome (day-runner) Pheidippides (famed by the 1879 Robert Browning poem of the same name) who delivered the news of victory at Marathon to the expectant Athenians; the proud motto of such messengers (in fact of their Persian counterparts) read, ‘… and neither snow nor rain nor heat nor night holds back from the accomplishment.’92 According to Plutarch, Eucles was a self-sent messenger who arrived in full armour from the battle he fought in himself. The Athenian Pheidippides (or Philippides, according to Lucian) apparently ran to Sparta to request help before the battle commenced, and he met the god Pan on the way, for legend had it that the god’s cave in the Parthenian ridge overhanging Tegea, was en route. In fact it was Euchidas, running the route to Delphi, who allegedly died on the spot.93 An amalgam of truths with popular fiction is what we recite today, when ‘eager to adopt and adorn the fable’, writers embellished the subject ‘as if it were the soil of a fair estate unoccupied’.94

Sparta’s own heroic holding of the pass against Xerxes’ Persian horde is itself shrouded in legendary misattribution, for the 4,200 reported defenders at Thermopylae are widely bypassed in eulogies that alone immortalise the alleged 300 Spartans who led them, though the numbers given by Herodotus (who claimed to know the 300 by name) are open to question (perhaps short by 700 or more in total), as is the Spartan-led night attack on Xerxes’ tent mentioned by Diodorus who was likely drawing from Ephorus, who in turn took this detail from an unknown source.95

And this leads us to the exemplar of a laconic retort by Leonidas to the Great King’s demand that the Greeks hand over their arms: molon labe – ‘you come and take them’. It is a bold riposte, and yet one taken from the Apophthegmata Lakonika, Laconian Sayings, attributed to Plutarch (now grouped with his Moralia) and compiled over 500 years after the event. Moreover, the historical pragmatist would ask: if the defenders died to the last man, could a Greek have recorded Leonidas’ reply? The son of the seer, Megistias, sent home the penultimate day, is a possible contender, and the exiled Spartan king, Demaratus (ruled 515-491 BCE), who accompanied the Persians on the north side of the Hot Pillars (the literal translation of Thermo Pylai) is perhaps a stronger candidate, though we should recall, when dealing with Spartan legend, that Lycurgus (ca. 390-324 BCE), the forefather who supposedly gave Sparta its polity, has been termed nothing more than a ‘benevolent myth’.96

The lyric poet Tyrtaeus (likely 7th century BCE) was probably more responsible for the militarisation of the Spartan constitution, if we can believe the claims in the Suda; his military elegies certainly encouraged the nineteen-year Messenian Wars that led to their enslavement of the helots, if the fragments we have are indicative of its overall tone and despite the Attic propaganda that described the poet as ‘a lame Athenian schoolmaster’.97

What did Alexander himself conclude about his sources 2,300 years ago when carrying Herodotus and the philosopher-edited Iliad into an Asia he only knew from their scrolls or from Aristotle’s teachings at Mieza?98 When Alexander finally joined battle with Darius III, where were Herodotus’ famed 10,000 ‘Immortals’ (a description unique to him), the Great King’s elite royal guard that the Macedonians expected to face? The answer is probably reincarnated in the melophoroi, so-called Apple Bearers, who were named after the fruit-like counter-weights on their spear butts, for Herodotus had most likely confused the Persian term ‘Anûšiya’ with ‘Anauša’, which simply meant ‘Companion’.99 Herodotus himself is said to have quipped: ‘Very few things happen at the right time, and the rest do not happen at all. The conscientious historian will correct these defects.’ But who can find the comedic lines within the historian’s work? It was in fact Mark Twain who attributed the words to him in the preface to A Horse’s Tail.100

Given time and propagated convincingly enough, this may well become a ‘genuine’ metaphrase that will further tarnish Herodotus’ reputation, for no historian has been more maligned (perhaps because he was a barbarophile) than the ‘father of history’ from Halicarnassus ‘who attempted to open up the gates to the past’. Plutarch penned a De Heroditi Malignitate (On the Malice of Herodotus), which has been termed literature’s ‘first slashing review’;101 the attack may have been in part due to Herodotus’ religious cynicism that offended the deeply pious Priest of Apollo, and the negative picture he painted of Plutarch’s fellow Boeotians.102 Valerius Pollio, Aelius Harpocration and Libanius followed suit with declamatory texts against the Histories, and Aristotle branded Herodotus a ‘teller of myths’ above anything else.103 Perhaps the greatest disservice paid to him was a two-book epitome of the Histories by Theopompus.104

Herodotus, ‘who blended the empirical attitude of the scientists with the rhapsode’s love of praising famous men’, nevertheless, offered in defence to the accusation, ‘that he sometimes wrote for children and at other times for philosophers’: ‘My business is to record what people say, but I am by no means bound to believe it, and let this statement hold for my entire account.’105 The apologia was a popular prenuptial in the marriage of the historikon and mythistoria. He nevertheless remains unique; as Momigliano concluded simply: ‘There was no Herodotus before Herodotus’, moreover, ‘he was more easily criticised than replaced’.106

This, in turn, draws us by the bridle and halter to Alexander’s breaking of Bucephalus, the king’s Thessalian warhorse which was probably named after its ox-head branding (boos kephale). The rendering of the story fitted the overall encomiastic portrayal of the young prince: he was a Bellerophon mounting a wild Pegasus that could be only tamed by him before an incredulous Macedonian court and an elated horse-dealer, Philonicus. Yet the event, which ‘abounds in circumstantial detail and dramatic immediacy’, was preserved by Plutarch alone, as was Alexander’s quizzing of Persian envoys on military detail at an even younger age, for this anticipated, and set the tone for, his later invasion of Asia.107 Did Onesicritus’ hagiographical The Education of Alexander (or Marsyas’ book of the same name) provide the models, or did Plutarch, in his ‘quiet naivety’, find this detail in the epistolary corpus he uniquely referred to on some thirty occasions?108 Surely neither source was reliable. Was the Bucephalus episode an allusion to the metaphor in Plato’s Phaedra which likened the untamed horse to an unruly youth who must be broken by an education, paideia, itself steeped in Homeric values? In which case it is fully understandable why Bucephalus ‘was born to share Alexander’s fate’ in the Romance.109

The careers of Plutarch, Callisthenes, Demosthenes and Aristotle, each influential to Alexander’s story, have also given birth to a spurious epistolary corpus in their name. Plutarch seems to have had unique access to a folio of correspondences to and from Alexander, so numerous that he commented: ‘In fact it is astonishing that he [Alexander] could find time to write so many letters to his friends.’110 Confirmation that a collection once existed, possibly collated as a book, came with the discovery of papyri in Hamburg, Florence and Oxyrhynchus in Egypt, though suspiciously ‘there is no trace of them earlier than Cicero’s De Officiis’ which referred to epistulae Philippi ad Alexandrum et Antipatri ad Cassandrum et Antigoni ad Philippum filium;111 the title suggests there once existed a corpus of letters between Philip and Alexander, and correspondence between Antipater, Cassander and Antigonus Monophthalmos, the remarkable Macedonian ‘one-eyed’ general.

Arrian also referred to the collection and it is likely a common source was behind the tradition.112 Plutarch’s folio was even more specific; those letters written to Alexander’s mother, Olympias, were ‘private’, and only Alexander’s closest friend, Hephaestion, was permitted to read them. Nevertheless, the detail we garner from them appears, in hindsight, to be fictitious. The authenticity of one of Plutarch’s own works remains just as vexatious; a Greek manuscript attributed to him and titled Pro Nobilitate, In Favour of Noble Birth, resurfaced as recently as 1722 and was not convincingly discredited until the late 1900s. Yet separating deliberate imposters from well-meaning ‘impostures’ is not always achievable.113 And so the authenticity of similar correspondence by the philosophers Plato, Speusippus (Plato’s nephew, ca. 408-338 BCE), Archytas (428-347 BCE) and the influential rhetorician Isocrates, whose pleas for an invasion of Persia arguably motivated Philip II (and then Alexander) to launch his Asian campaign, is still debated.114 But the composition of such letters, in emulation of the great minds of the past, was a part of Greek classroom preparatory exercises, progymnasmata.

Some thirty-plus letters concerning Alexander made their way into the Greek Alexander Romance, a publication unique in ancient fiction in the breadth of its epistolary ‘pseudo-documentarism’. Examples range from what Merkelbach termed wunder-briefe to the almost credible, a state of affairs that epitomises the whole Romance.115 Plutarch may have been unwittingly incorporating letters that had no historical foundation into his own biographies, perhaps fooled by the freehand-form of their intimacy when no stylistic baseline for comparison existed. They may have even originated, convincingly, with a court scandalmonger such as Chares, the king’s chamberlain. So the argument about the ‘truth’ revolves around the degree of trust we place in the instincts of our secondary sources and their immunity to seduction.

The association of the authorship of Romance with the campaign historian Callisthenes (besides other historians) reminds us that we commonly place credit where none is due, when the real architects of events may disappear without a trace. With a superficial knowledge of characters and the events attached to them, we risk, once again, creating our own modern ‘romances’ when regurgitating the tale. We habitually lay down Mercator-like projections on history’s prosopographic terroir; but this is a one-dimensional mapping that distorts both the shape and the scale of contributions, for the truth lies hidden in contours and grottos time has flattened out.

Examples proliferate the classical accounts: Pythagoras’ theorem still bears his name, yet the triplets had already been in use in Babylon and Egypt for over 1,500 years before his day, since the Middle Bronze Age in fact.116 If Porphyry is correct, Pythagoras took his knowledge of geometry from Egypt, arithmetic from Phoenicia, astronomy from Chaldeans, and principles of religion from the Magi too,117 which is no doubt why Plato is said to have paid the exorbitant sum of 100 minas to purchase three books of Pythagorean doctrine by Philolaus of Croton.118 Plutarch’s Symposiacs provided further detail of his teachings but these were penned some 500 years later using notes left behind by the polymath’s inner circle, the mathematikoi and akousmatikoi, the ‘learners’ and ‘listeners’.119

Pythagoras’ association with the newly ‘discovered’ geometry was in fact first made by Cicero in his On the Nature of the Gods. Cicero had been a political survivor par excellence, until Mark Antony presented Octavian with his proscription list, but without his 800 extant letters would we have known he was a giant of the Julian age? Or would his bit part of just nine lines in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar have swayed us otherwise? If it was not for Petrarch’s discovery of the Ciceronian epistolary collection, ad Atticum, in Verona in 1345, which contained such a wealth of detail that Nepos had believed there was little need for a history of that period,120 we would only have half the correspondence; inevitably some of the corpus does appear less than genuine.121 Petrarch, whose epic but unfinished Africa – a poem perhaps written as a reply to the Alexandreis of Gautier de Chatillon and written in the style of Virgil’s Aeneid – was so excited about his find that he compiled a letter to the long-dead Cicero to tell him (and to Livy too). And could either Cicero, or Julius Caesar even, have made the historical grade if not for Apollonius Molon’s lessons in Rhodian rhetoric?122

If the inscriptions found at Nineveh have been deciphered correctly, the so-called Archimedes Screw was also in use centuries before Archimedes ‘stumbled’ upon the idea.123 And on the subject of water management, De Lesseps’ canal at Suez remains a wonder of the industrial revolution, but Aristotle, Diodorus, Strabo and Pliny each placed an original channel linking the two oceans (though indirectly and via a different route) in the time of the Egyptian pharaohs. The first excavations possibly commenced with Merenre I of the Sixth Dynasty in the late third millennium BCE, though sources better corroborate the early efforts of Sesostris (ca. 1878-1839 BCE, probably identifiable with Senusret III).124 Re-excavation of the watercourse had commenced around 600 BCE, centuries before Alexander crossed the Nile, which was named the Aegyptus River in antiquity, though in Greek mythology Aegyptus was a descendent of the river-god Neilus.125

Pharaoh Necho II (ruled ca. 610-595 BCE) stopped construction of the waterway when an oracle warned him he was ‘working for the advantage of a barbarian’, though by then, according to Herodotus, some 120,000 Egyptians had died in the construction efforts. Another tradition picked up by Aristotle more practically suggested that engineers had advised against contaminating the freshwater Nile with salt, for the channel linked the Red Sea (thought to be at a higher level than Lower Egypt) to the river and not directly to the Mediterranean.126 The canal was finally completed by Darius I whose inscription commemorating the project survives to this day; according to Herodotus the waterway was sufficiently wide for two triremes to pass and Ptolemy II Philadelphos had it re-excavated to the Bitter Lakes using navigable locks and sluices to prevent the in-flow of seawater; it was known as the ‘Ptolemy River’.

Excavated papyri do reveal a remarkable irrigation system in the Fayyum basin south of Memphis, which drained marshland that was otherwise uninhabitable and reclaimed valuable settlement areas for Egyptians and Hellenic mercenaries alike through to the mid-3rd century BCE.127 Rome would later benefit from the engineering feat and Trajan extended the canal system with a branch known as the Amnis Trajanus, which joined the Nile somewhere close to Memphis (which was some 12 miles south of modern Cairo). Remnants of an ancient East-West canal were indeed found by Napoleon’s cartographers in 1799 along with an emaciated Alexandria with barely 6,000 inhabitants; Napoleon reincarnated the idea of putting it back into service, though the canons of the British navy did not allow him the opportunity.128

Rome’s own enigmatic past is not beyond question. The ‘legend’ of Coriolanus (5th century BCE), a vivid narrative of a hero turned enemy, was scooped up by Livy, Plutarch and Dionysius, amongst others. Although Plutarch confidently afforded him a lineage (and a nickname) and a fifty-page biography, the consular fasti (official records) never mentioned Coriolanus at all, yet they record the siege of Corioli and the Volscian uprising that supposedly made him.129 Was he a figure invented to warn the Senate of the unbridled power of popular generals and kings, or a representation of aristocratic tyranny over the city’s plebeian interests? For these themes were prominent in the early days of Rome; Livy recorded the fall of the Etruscan city of Veii, which was alienated by the remaining tribes for its abhorrent adherence to monarchy.130

It is worth noting that new linguistic investigation suggests the Etruscans, to whom Rome ‘owed much of its civilisation’, may well have been refugees from fallen Troy (Herodotus reported they emigrated from Lydia in Asia ca. 1,000 BCE), though Augustus, Naevius, Ennius (ca. 239-169 BCE) and Virgil (70-19 BCE) would be mortified to hear it. Certainly, some of the paintings on the walls of Etruscan tombs (6th century BCE), somewhat Greek in style, have Phrygian and Lycian points of comparison. Etruscan offerings (7th century BCE) have been found at Olympia, suggesting continuous early contact with Greece.131 Trosia, the Greek name (alongside Ilium) for the city of Priam, resonates with similarity to the frequent Hittite and Egyptian references to Turush and Trusya that appeared in 14th and 15th century BCE documents, and thus, it is suggested, to later Tros or Trus, the supposed roots of the names ‘Etruria’ and ‘Etruscans’. What was once a fanciful notion is now backed up by the identification of genetic similarities,132 though as one historian noted of the Etruscan civilisation and its supposedly indecipherable texts: ‘I don’t think there is any field of human knowledge in which there is such a daft cleavage between what has been scientifically ascertained and the unshakable belief of the public…’133 But the same could perhaps be stated, of course, of Alexander himself.

THE INCOMPARABLE COMPARANDUM AND THE NEW SACK OF ILIUM

Alexander’s character portrayal survives as a Graeco-Roman amalgam that is analysed against the backdrop of ever-changing contemporary ideals. But the comparisons inevitably made are not always digestible. Texts are unambiguous that Caligula (alternatively Gaius, 12-41 CE) was something of a monster who paraded himself in Alexander’s breastplate, which he claimed was taken from the now-lost Alexandrine sarcophagus.134 But are we troubled, or inspired, by Alexander’s own heroic emulation? For he relieved the guardians of the Temple of Athena at Troy of Achilles’ shield, or so he believed. The deeds are comparable but the men are not, and so we revile the one while admiring the Homeric homage being paid by the other. If Schliemann had not staked his claim to Troy in 1868, the value we place on what we deem ‘court’ sources may have been quite different, for Arrian, for one, claimed Alexander found the site easily enough upon beaching at the Troad and sacrificing at the tombs of his heroes, where Strabo stated little identifying evidence of the site remained.135

Alexander’s own Homeric shield-coveting might have been inspired by tales of Pythagoras, who, through eternal transmigration, claimed to be a reincarnation of a Trojan hero. He was, he believed, Euphorbus, who had been cut down by Menelaus in the fight over Patroclus’ body, a story put to verse in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a ‘compendium of myth’ written in the dactylic hexameter of the Epic Cyle. Unlike the Socratic belief that all knowledge of a previous life was washed away with each rebirth, Pythagoras had been, he claimed, granted eternal memory as part of the gift from Mercury. As ‘proof’ of his past when inhabiting the reincarnated body of Hermotimus, he apparently went to the (original) territory of the Branchidae and tracked down the beaten shield (by now worn down to the ivory) that Menelaus had retrieved from the battlefield and dedicated to the temple of Apollo.136 Whether Pythagoras or Alexander truly believed they had the genuine defensive armour of the Trojans is a matter of conjecture, but in Alexander’s case that would have meant that the hoplon he actually used in battle was more than 800 years old; what he had retrieved from the Athena’s temple was surely a symbolic talisman rather than a functional shield.137

Alexander also shared intriguing parallels with the Roman emperor Nero, who should feature prominently in any chapter dedicated to the vivid hues of romance. An open admirer of the Macedonian conqueror, Nero formed an elite personal unit staffed exclusively by men over 6 feet tall and he named it The Phalanx of Alexander the Great;138 according to the Suda, an Alexander of Aegae was even employed as one of Nero’s tutors.139 The excesses and colour that epitomised Nero’s imperium became legendary and fascinated the citizens of an expanding empire.140 Everyone related to something of the emperor, and paradoxically, besides the havoc he wrought, the populace remained curiously nostalgic for Nero’s eccentricities. Even his choice of a ‘proud whore’ as second wife (Poppea Sabina) must have appealed to those outside the elite patricians and nobiles. Dio Chrysostom recorded their enthusiasm: ‘… for so far as the rest of his subjects were concerned, there was nothing to prevent his continuing to be emperor for all time, seeing that even now everybody wishes he were still alive. And the great majority believe that he still is…’141

A 17th century sculpture of Nero at the Musei Capitolino, Hall of Emperors, Rome. A part of it is original giving form to the reconstruction. Suetonius provided a vivid description of the emperor: ‘He was about the average height, his body marked with spots and malodorous, his hair light blond, his features regular rather than attractive, his eyes blue and somewhat weak, his neck over thick, his belly prominent, and his legs very slender… he was utterly shameless in the care of his person and in his dress, always having his hair arranged in tiers of curls.’145

Chrysostom’s final line brings us to the most significant parallel with Alexander: the ‘false’ Neros that appeared. For many did believe he never committed suicide but rather lived on in obscurity; at least three imposters presented themselves as the living emperor over the next twenty years and with subjects ready to accept them.142 Cassius Dio (ca. 155-235 CE) reported that in 221 CE, a century and a half on, a mysterious person appeared at the Danube with an entourage and claimed to be Alexander the Great. Entranced by the apparition (an eidolon to the Greeks), none dared to oppose his progress; on the contrary, they provided him with food and lodging. After performing nocturnal rituals and burying a wooden horse, he disappeared once more.143 As for Nero, it was the developing Sibylline Oracles that took the thespian emperor to the realms of apocalyptic legend through to the City of God of Augustine of Hippo (354-430 CE, also known as ‘Saint Augustine’), which criticised the portrayal of him as the Antichrist, and like Alexander, Nero entered the folklore of the Middle Ages.144

Nero had forced his teacher, Seneca (‘the Younger’, ca. 4 BCE-65 CE), and his teacher’s nephew, the celebrated poet Lucan, to commit suicide, claiming they both had a part in the Pisonian plot to remove him.146 In fact Nero simply wished to put an end to Seneca’s criticism of his increasingly bizarre behaviour following his alleged murder of his own mother, Agrippina; Nero claimed that Seneca had amassed the remarkable (and highly suspicious) sum of some 300,000,000 sestertii in just four years under his patronage.147 The Apocolocyntosis (loosely translated as the ‘pumpkinification’) of the Divine Claudius, flattering to Nero and possibly written by Seneca shortly after Claudius’ death (in 54 CE), suggested this Stoic teacher once held high hopes for his new ‘radiant-faced’ Nero. Alas, after some promising years, the trappings of imperium saw the ‘new star’ begin to fade. The demise of Lucan, once an imperial friend and holding a questorship and augurate at a remarkably early age, stemmed ultimately from the republican sympathy embedded within the later books of his De Bello Civili.148 This led to the banning of his poetry, including the De Incendiis Urbis, On the Burning of the City, in which Lucan termed Nero a tyrant, and that paralleled his critique of the conquering Alexander. Lucan was forced to open his veins at the age of twenty-five.149

The parallel here is Callisthenes, Alexander’s own outspoken historian. He had opened promisingly for Alexander too; seas parted and the gods took due notice of their favourite new son. However, his distaste for Alexander’s oriental adoptions, divine pretensions and perhaps, finally, the wholesale slaughter of the defenceless Branchidae, saw him forget Aristotle’s warnings and he let loose his indiscreet tongue. He too was executed on the king’s orders; according to one tradition, quite possibly again stemming from Greek polemic emanating from the Peripatetic school, Callisthenes was first caged for some years and dragged around in chains before being tortured. Perhaps he saw it coming: once offered undiluted wine at a court komos, he reportedly declined with, ‘I do not wish to drink Alexander’s cup and then need the cup of Asclepius’, the healing god.150 The comparison with Nero is rarely made but the crime was ultimately the same.

Philosophers were the bane of kings, emperors and even democracies, as was Diogenes the Cynic of Sinope. Alexander visited the barrel-bound philosopher in Corinth in 334 BCE shortly after the destruction of Thebes, and he enquired if there was anything that Diogenes desired. In the legendary anecdote captured by Plutarch (and others), Diogenes asked Alexander to step aside as he was blocking his sun.151 Tradition claims that this prompted the Macedonian king to confide to his companions that ‘… if he were not Alexander he would like to be Diogenes.’ The unlikely dialogue, probably the output of the Diogenes’ Cynic school, ought to be shadowed in historical reality.152 Superficially impressive in its hauteur as his reply was, any biography of Diogenes would not be complete without mentioning his public behaviour, which included defecation and masturbation, leading Plato to brand him (and Diogenes to brand himself, for that matter) a dog, kynos, the root of the word ‘cynic’; it was behaviour supposed to emphasise his objection to ‘regressive’ civilisation.153

A former slave captured by pirates, and one charged with debasing (or defacing) the local currency at his native Sinope (a charge carrying severe penalty),154 Diogenes had found the clay barrel (or urn) in which he slept in the Temple of Cybele. He might have been the first true ‘citizen of the world’, kosmopolites, a concept the Stoikoi later took up when Rome was indeed assimilating much of the known world.155 But there were, in fact, a number of traditions floating around involving Alexander and the ‘dog’ he so admired. Plutarch’s Moralia claimed Diogenes expired on the same day as Alexander, whilst another writer has him brought before Philip II after the Athenian defeat at Chaeronea; when questioned on his identity Diogenes replied he was ‘a spy, to spy upon your insatiability’ following which his amused captor set him free.156 A further story, which proliferated in later works, claimed Alexander found the philosopher rummaging through a pile of bones; when asked why, Diogenes replied: ‘I am looking for the bones of your father, but cannot distinguish them from those of a slave.’ No doubt allegorical too, it bears the hallmarks of Lucian’s Menippus, a dialogue featuring the 3rd century Cynic-satirist whose style he often imitated,157 and it remains highly unlikely that the ‘mad Socrates’, as Plato called Diogenes, would have been worthy of Alexander’s continued esteem.158

THE GIRDLE OF HIPPOLYTE

Plutarch was always creative when dealing with a scandal. In a campaign episode that featured the legendary Amazons he named fourteen different sources that either confirmed, or repudiated, Alexander’s affair with their tribal queen, Thalestris. Superficially, the incident is quaint and much developed in the Romance, however, for our study, it is a tutorial on the grey matter between the black and white.159 Of those sources cited, five declared for the meeting, and nine, according to Plutarch, maintained it was a fiction. Notably, one of the five was Onesicritus, supposedly an eyewitness to the event. Another was Cleitarchus who likely followed Onesicritus’ lead. Surprisingly, one of the nine doubters was Chares the royal usher who had an interest in court scandaleuse; Ptolemy and Aristobulus also came down on the side of invention.160

Plutarch named six historians who are little known or unique to this passage and their responses, it seems, confirmed it either happened, or it did not. But we need to tread carefully, for in the same passage Plutarch confirmed Alexander did write to his Macedonian regent to report his meeting with a Scythian king who offered him his daughter. Moreover, the Macedonians were indeed close to Amazon country, the relevant part of southern Scythia attached to the legend popular since the Iliad. Scythian ‘warrior women’ are known to have existed; modern excavation of burial sites prove female warrior bands operated amongst the Sacan nomads, and Amazonomachy (art depicting Greeks fighting Amazons, often equipped with light battle-axes), much of it based on Heracles’ Ninth Labour, adorned everything from the Parthenon, the Painted Stoa and the Temple of Zeus at Olympia.161 Although Plutarch saw the presence of the Scythian king as a vindication of the doubters, it nevertheless confirmed that an event that broadly approximated the reports could have in fact taken place.

Arrian recorded the presence of embassies from various Scythian tribes as Alexander progressed through Asia; when reporting that Atropates, the satrap of Media, sent one hundred women dressed as Amazons to the Macedonian king, he reminded us of their frequent appearances in the Histories of Herodotus, which recounted Heracles’ task of bringing the girdle of their queen, Hippolyte, back to Greece. Arrian concluded with: ‘I cannot believe that this race of women never existed at all, when so many authorities have celebrated them.’162 But regardless of their historicity, if Alexander was presenting himself as a new Achilles, as sources appears to confirm, then the hero needed an encounter with his own Penthesilea, the legendary Amazon queen who turned up to defend Troy and take on the famed warrior.163 That Alexander seduced an Amazon where Achilles stabbed her instead, did not lessen the romantic parallel. The spectacular shield found in Tomb II at Vergina may in fact bear the imagery of that legendary Trojan encounter as its centrepiece in ivory and gold.164

So can we blame Onesicritus for what may amount to a modest embellishment of truth inspired by the Median episode? Upon hearing Onesicritus recount the episode, Lysimachus’ cynical quip – ‘Where was I then?’ – may have been targeted at the thirteen-day tryst Alexander allegedly enjoyed with the queen (assuming Onesicritus covered that too) and not at the meeting itself.165 Furthermore, Lysimachus’ criticism appears singular, which might suggest that on the whole Onesicritus narrated events that were supportable. That itself appears misleading, for we have examples of far more fabulous claims from him concerning the wonders of India: living dragons, three-hundred-year-old elephants and 200-feet-long serpents among them.166 So we in turn may ask: ‘Where were all the Macedonians then?’

Another of Alexander’s famous liaisons involved Cleophis, the mother of the Indian dynast, Assacenus, and whose robust defence of Massaga (today’s Swat region of Pakistan) brought her to Alexander’s attention. Latin tradition (only) portrayed Alexander as impressed with her beauty and Justin went as far as claiming he fathered a son with her, also named Alexander, with Cleophis retaining her position through ongoing sexual favours; Curtius simply stated she bore a so-named child. The historicity of the story is, however, clouded by Alexander’s massacre of the mercenary contingent of Massaga which ‘stained his career’; if, on the other hand, this dishonourable conclusion was Roman-era scandal from Trogus or Timagenes, and recalling Cleopatra’s similar seduction of Julius Caesar and Mark Antony, the Cleophis affair may well have inspired the legend behind Alexander’s affair with Candace of Meroe in the Romance.167

Clearly, this genre of ‘romantic’ material, based on the seductions of, and by, the Macedonian king, has endured in the ‘mainstream’ accounts. Should ‘romances’ then be so easily dismissed and relegated behind their ‘serious’ counterparts? Our point, illustrated from various angles, is that the dividing line between fiction and fact is subtle, like the ‘all-too-narrow isthmus’ Lucian proposed marked off ‘history from panegyric’.168 And it was often muddied over by the debris of romance, leaving us guessing if we are dealing with plausible impossibilities, or rather, implausible possibilities.

THE KALEIDOSCOPIC BIRTH OF THE LEGEND

What made Alexander’s story so ripe for ‘romancing’ when, as an example, the life of Julius Caesar – paralleled with Alexander’s in Plutarch’s Lives – was not? Certainly without the thauma, the marvels developed by the fabulously inclined biographers, Ptolemy’s sober military treatise would not have provided sufficient flammable tinder either. It required hagiographies and panegyrics to blow on the fire, and a death in distant Babylon, not on the steps of the Theatre of Pompey in a no-nonsense and fractious Rome. Strabo sensed it when he wrote of Alexander historians: ‘These toy with facts, both because of the glory of Alexander and because his expedition reached the ends of Asia, far away from us.’169 Caesar had in fact stood before the statue of the Macedonian with its outstretched arm in the Temple of Heracles (now Roman Hercules) at Gades, modern Cadiz, when he was quaestor of Hispania Ulterior; vexed at his comparatively slow progress to greatness, he is said to have sighed impatiently. The statue remained standing until the 12th century by which time Arab authors proposed Alexander had himself excavated the Straits of Gibraltar.170

Both Caesar and Alexander had understood the need to lay their achievements down in writing when fresh, pliable, and untarnished by partiality and the reasoned balance of hindsight. Alexander had Callisthenes and Onesicritus on the spot to do the job, whereas Caesar himself penned his own Gallic War diaries, ‘… incomparable models for military dispatches. But histories they are not…’ There are ten surviving manuscripts of Caesar’s commentaries on the war in Gaul and none of them mentioned the estimated one million slaves taken between 58-51 BCE.171 But Quellenforschung would rule both approaches unfair, a partiality uniquely manifested when the recorder of the episodes was either employed by their architect, or the architect himself; as far as Caesar’s Commentarii, as Wilkes points out, they ‘acquired authority in later years, not because they were invariably more reliable’ but because his followers ‘could allow no other version to prevail’.172 Nevertheless, Cicero praised them for their simplicity, straightforwardness and grace, and he found them ‘stripped of all rhetorical adornment’, so much so that it ‘kept men of any sense from touching the subject’.173 Had Caesar wanted an enduring romance, it seems he ought to have outsourced to an author in Egypt.

Highly readable romances were more easily assimilated than the more challenging and often lengthy classical histories, in much the same way that Cleitarchus’ Alexander eclipsed the primary sources it subsumed. This was something of a literary Oedipus complex, when the parental work is rejected by the collusion of later sibling texts that were drawn to the story. But it remains impossible to pinpoint Alexander’s Romance equivalent of ‘Chrétien de Troyes’, the first writer to mention the Arthurian Holy Grail.174 Yet, as with the jongleurs, the Middle Age troubadours who kept Arthur in circulation, and the authors of the Four Continuations who diversified and accessorised the tale, there was probably no single influence that gave the Romance its birth, and there would have been a number of ‘pre-texts’, as Fraser termed them, behind the first edition.175