5

CLASSICUS SCRIPTOR, RHETORIC AND ROME

Did the Roman-era historians faithfully preserve the detail they found in the accounts of Alexander’s contemporaries?

The surviving biographies of Alexander and his successors are the output of the Roman-era. These are ‘secondary’ or even ‘tertiary’ sources whose testimony may have come to us through intermediary historians, some of them still anonymous. They were products of a no-less challenging environment than their Greek and Macedonian predecessors, as Rome’s republic was transformed into an empire and free speech all but disappeared. Vulnerable to the censorship of warring dictators or a lengthening imperial shadow, these writers overlaid their own contemplations, biases and ideologies – and inevitably those of the state – on the story of Alexander.

We look at the effects of the prevailing doctrines and rhetoric to appreciate the extent to which Alexander was misrepresented, misinterpreted or simply mishandled by the Roman-era historians.

‘It is hardly surprising if this material [the polished arrangement of words] has not yet been illustrated on this language, for not one of our people dedicated himself to eloquence, unless he could shine in court cases and in the forum. The most eloquent of the Greeks, however, removed from judicial cases, applied themselves first to other matters and then especially to writing history.’1

Quoting Marcus Antonius in Cicero De Oratore

‘Eusebius, like any other educated man, knew what proper history was. He knew that it was a rhetorical work with a maximum of invented speeches and a minimum of authentic documents.’2

Arnaldo Momigliano Essays in Ancient and Modern Historiography

‘This is not the site of ancient Ilium, if one considers the matter in accordance with Homer’s account.’3

Strabo Geography

The city of Troy is still referred to as ‘legendary’. Yet Thucydides, Arrian, and Alexander, who commenced his campaign with sacrifices at what were presented to him as the tombs of his Homeric heroes, were never in any doubt of its past glory.4 Neither were the historians and geographers who dated the fall of the city anywhere from 1184 to 1334 BCE based upon the Dorian occupation of the Peloponnese supposedly two generations after.5

Modern excavations of the remains of the hill at Hissarlik in northwest Anatolia suggest some accuracy to Homeric geography, and this argues for Heinrich Schliemann’s 1868 dissertation Ithaka, der Peloponnes und Troja, in which ‘the father of Bronze Age archaeology’ first claimed his Trojan find, though the diplomat-archaeologist, Frank Calvert, and before him the geologist, Charles Maclaren, had significantly pointed the way.6 Yet the modest scale of the fortified mound, as Strabo’s Geography noted, argues against its fabled size. Moreover, archaic references to Troy remain somewhat ambiguous.

Dardanus (a son of Zeus and Electra) was supposedly the founder of an eponymous settlement (Dardania) in the Troad and also a tribe, the Dardanoi, who were referred to interchangeably as Trojans in some sources. But the nearby city of Troy was known to the Greeks of the classical world as both Ilios and Troia (or Trosia) after two of Dardanus’ descendants, Ilos and Tros. Wilusiya and Taruisa, two states comprising the Assuwan Confederacy listed in Hittite texts, remain contenders for the site whose origins were lost along with Greek knowledge of the Hittite Empire itself. References scattered through the texts of Herodotus and Strabo provide an interwoven genealogy of the tribes of Asia Minor, many with links to Crete as well as the legendary city, apparently justifying Homer’s inclusion of Cretans, Lycians, Ionians and Paphlagonians among the diverse allies in the defence of Troy.

Schliemann himself was not good at differentiating fact from legend and he has since been termed a ‘pathological liar’.7 Nine distinct ‘cities’ have now been identified in the Hissarlik mound and none has turned up a definitive link to the citadel of Priam. The last settlement, Novum Ilium, was planted by Rome, no doubt to reinforce her own ancestral claims.8 Rome was warned of rebuilding on the soil of Troy lest she suffer the same ill-fated fortune, and true to the prophecy, like its breached walls and the vaster empire of Alexander, her borders were to crumble and her temples were to fall.9

Alexander and Rome shared a common heritage and one symbolically apt for our claims. But if a homogenous metropolis had once existed in the Troad, does that mean the decade-long battle to bring its walls down was truly acted out? If the Epic Cycle is endemic to the recounting of Alexander’s deeds, it is a historical fusion that raises many questions. We know the Macedonian conqueror lived, but just as with the crumbled ruins at Hissarlik, do we have the genuine article, or are we treading the literary foundations of later Roman construction?

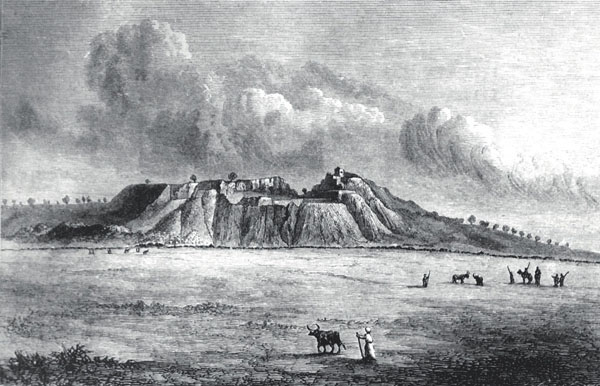

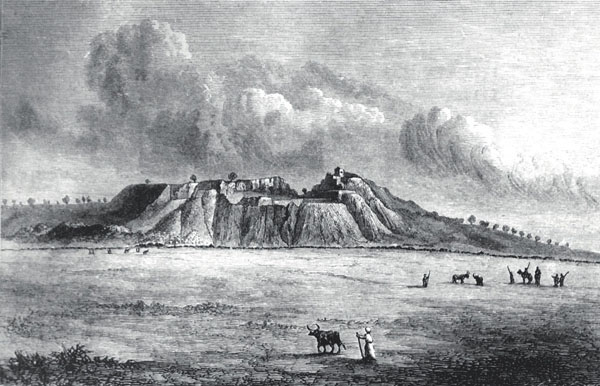

A plate titled ‘View of Hissarlik from the North. Frontispiece. After the Excavations. From the publication Troy and Its Remains. A Narrative of Researches and discoveries made on the site of Ilium, and in the Trojan Plain. By Dr. Henry Schliemann. Translated with the author’s sanction. Edited by Philip Smith, B.A., Author of History of the Ancient World and of the Student’s Ancient History of the East. With map, plans, views, and cuts, representing 500 objects of antiquity discovered on the site.’ Printed 1875.

THE NON-PRESERVING ASPIC OF ROME

The early accounts of Alexander’s contemporaries, and those sponsored by their courts, had to straddle the chaos of a Hellenistic world that saw the kingdoms of the Diadokhoi and their epigonoi absorbed by the expanding Roman super-state. The bloody process swallowed much of the literary output of the age so that the century before Polybius remains a ‘twilight zone’;10 for almost seventy years after the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE there is no surviving continuous coherent account, Justin’s severe epitome aside. Polybius himself stoically reflected in the opening of his book that the ‘… writings of the… “numerous historians”… whom the kings had engaged to recount their exploits have fallen into oblivion.’11

Diodorus, whose Bibliotheke unfortunately survives in tattered fragments for the post-Ipsus period and without the useful chapter proektheses (synopses or lists of the detail covered), also mourned the poorly documented years with a proem that underlined his own ‘universal’ efforts:

And of those who have undertaken this account of all peoples, not one has continued his history beyond the Macedonian period. For while some have closed their accounts with the deeds of Philip, others with those of Alexander, and some with the Diadokhoi or the Epigonoi, yet, despite the number and importance of the events subsequent to these and extending even to our own lifetime which have been left neglected, no historian has essayed to treat of them within the compass of a single narrative, because of the magnitude of the undertaking.12

The literary wasteland gives the superficial impression that in Rome’s sphere of influence, too, there was lack of interest in overseas history through this era, which, as McGing puts it, was neither ‘proper Greek history, which lost its appeal after Alexander, nor yet the vital part of proper Roman history…’13 But Rome had been establishing herself over the twelve-city confederation of the intensely pious Etruscans and other neighbouring tribes, which was clearly the early priority, and the war against Carthage (Qart-hadasht, ‘New City’ in Punic, Karthago to the Greeks) occupied its attention for the latter part of the period. Any trade delegations, government embassies, treaties and skirmishes that did take place between Rome and the Macedonian-dynasty-dominated Hellenic East in the post-Ipsus years were simply lost with intervening literature.

The narratives that did once knit the two worlds together once came from the now-lost works of Phylarchus (ca. 280-215 BCE), Aratus (ca. 271-213 BCE), Philochorus (ca. 340-261 BCE), Diyllus (ca. 340-280 BCE), and Demochares the nephew of Demosthenes, among a clutch of other names that have come to us through fragments. They included Hieronymus’ lost account which ended sometime soon after 272 BCE, and the non-extant history of Timaeus written in fifty years of exile in Athens (care of Agathocles the Sicilian tyrant) which closed at 264 BCE, the year Rome invaded his homeland, Sicily (he was from Tauromenium, modern Taormina). Diodorus’ fragmentary Bibliotheke had hardly made any mention of Rome until this point, which, significantly, marked the beginning of its control of his place of birth in Sicily too.

But it was Polybius, whose own account commenced in 264 BCE with the First Punic War between Rome and Carthage, who saw first-hand the final fall of the former Macedonian-governed empire to the Roman legions, though he failed (in what text survives at least) to acknowledge Hieronymus as a source of the post-Alexander years, which, as one scholar notes, is remarkable given their parallel themes: the rapid expansion of superpowers that had risen from obscurity, and with the one subsuming the other.14 Possibly influenced by his ‘tour of duty’ with Scipio, Polybius, who defined his work as pragmatike historia,15 believed the recording of history meant subordinating ‘the topics of genealogies and myths… the planting of colonies, foundations of cities and their ties of kinship’ to the greater significance of the ‘nations, cities and rulers’.16 So imperial 5th century BCE Athens, for example, was, in Momigliano’s view, ‘a distant unattractively democratic world’ to him, only salvaged, for a while, by enlightened leaders like Themistocles.17

Clearly familiar with (and influenced by) Herodotus, Thucydides and Xenophon, and highly opinionated on what ‘history’ should be, Polybius contended that monographs were inferior to his ‘universal’ approach. This was supposed to highlight that the earlier Greek accounts, especially those of the 4th century BCE, leaned to ‘the great leader theory of history’, focusing on single individuals and so revealing just dissected parts when the ‘whole body’ needed a post-mortem.18 The Greek historians had placed war, with its victors, the vanquished, and the proponents of war, centre-stage in their perception of epochal change. His criticism of Theopompus’ Philippika, now ‘double abbreviated’ through first Trogus and then his epitomiser Justin, brought the point home: ‘It would have been much more dignified and more just to include Philip’s achievements in the history of Greece, than to include the history of Greece in that of Philip.’19

Polybius began his main ‘holistic’ narrative of affairs in the Mediterranean Basin, in which he recorded Rome’s contact with the Diadokhoi kingdoms to the East, in the 140th Olympiad, so 221/220 BCE,20 the year Philip V ascended the throne of Macedonia and Hannibal Barca was appointed commander of Carthaginian forces in Spain. Unsurprisingly, he never actually named the Alexander-era historians at all, save Callisthenes and in a somewhat disparaging manner;21 his fourteen digressions on Alexander’s behaviour (besides five passing references), which offered little unique material, provided him little more than a somewhat stoical mixed review.22 Nevertheless, these monographs, and Theopompus’ unique character focus, provided Polybius with the anonymous essences he slotted into his ‘entire network’ with its many ‘interdependences’.23

True to his polemical literary ancestral roots, Polybius didn’t shy away from attacking ‘competing’ historians, Phylarchus, Philinus and Fabius Pictor, for example, who covered the wars with Carthage.24 He was also highly critical of his forerunner, the long-lived Timaeus (Lucian claimed he lived to age 96), whose Olympiad reckoning system Polybius nevertheless adopted to calibrate his own chapters which commenced at the point at which Timaeus had closed his (the 129th Olympiad).25 His loud invective against Timaeus, ironically, preserved much of the detail he had set out to destroy, and yet Polybius’ charity ‘was conspicuously lacking’, for he also proposed: ‘We should not find fault with writers for their omissions and mistakes, and should praise and admire them, considering the times they lived in, for having ascertained something on the subject and advanced our knowledge.’26

Timaeus’ account, rich in detail of colonies, city foundations and genealogies (and highlighted coincidences – all the detail Polybius ‘subordinated’), was probably worthy of a place on the shelves,27 but the exiled Sicilian had himself famously criticised everyone and gained the title epitimaeus, ‘slanderer’, along the way; he must have invited additional criticism when he spuriously dated Rome’s founding to 814/813 BCE (the thirty-eighth year before the first Olympiad) to synchronise it to Carthage’s in order to imply the cities enjoyed twinned fates.28 Possibly despising Timaeus for his self-declared lack of military experience, Polybius’ summing up did elucidate the principal problem of the day: Timaeus ‘… was like a man in a school of rhetoric, attempting to speak on a given subject, and show off his rhetorical power, but gives no report of what was actually spoken.’29

But Polybius didn’t remain faithful to his own critiques; he is branded a prejudiced eyewitness to the calamitous events of his day, and the frequent reconstituted speeches we read in Polybius were the product of his ‘subjective operations’. His directionless last ten books read like personal memoirs ‘focused on himself’ in order to ‘write himself into Roman history’.30 In the opinion of one Greek scholar, Polybius could be ‘… as unreliable as the worst sensationalist scandalmonger historians of antiquity, provided that he is out of sympathy with his subject matter.’31 If pragmatic his history was, at times holistic it was not in unravelling events. Yet within Polybius’ focus on contemporary affairs, his assessment of constitutions articulated the notion of anakyklosis; this presented the theory, and even the prediction, of the evolution of governance through time.

Building on the discourses of Plato and Aristotle, as well as the sequence of empires described by Herodotus, his system of cyclical inevitability saw the rise and fall of city-states and their empires from ‘primitive’ monarchy through to (developed) monarchy, tyranny, aristocracy, oligarchy, democracy, ochlocracy (mob rule), and finally back to the beginning of the cycle with some form of monarchy.32 Ironically, Polybius considered Athens at her prime as verging on ochlocracy (Plato might have agreed, for its demokratia had overseen the death of his friend and mentor, Socrates). He further believed that Rome’s republican system of government, a ‘mixed constitution’ (a hybrid that contained elements of a monarchy, aristocracy and democracy), had broken the chain, and though he was not suggesting that this would prevent its natural decline, signs of which he pointed to even in his day, Rome was, in fact, to become a fine example of the politeion anakyklosis.33

As part of his perception of change, Polybius expressed an appreciation of what we might term ‘globalism’:

Now in earlier times the world’s history had consisted so to speak of a series of unrelated episodes, the origins and results of which being as widely separated as their localities, but from this point onwards history becomes an organic whole: the affairs of Italy and Africa are connected with those of Asia and of Greece, and all events bear a relationship and contribute to a single end.34

Whilst he credited Alexander’s Asian empire with opening up the East, for him, this ‘organic whole’ now meant ‘Rome’ in her stellar fifty-three-year rise to rule the then-known world, ‘Fortune’s showpiece’ as he described it.35 Whether he was truly in awe of Rome and her conquests, or simply disdainful of her sway over Greece, we may never know, but (indirect) vexatious references we see in his books suggest the Romans were considered barbaroi, amongst the barbarian tribes.36

The pre-Polybian ‘twilight zone’ had its sequel, however, when ‘an even more vexatious twilight descends’ on Hellenistic history after Polybius passed.37 Although homebred Roman historians were spurred into action after the Second Punic War (or ‘Hannibalic War’, 218-201 BCE), they focused on the progress of the mother city through the Annales Maximi and not on gathering in the detail of the broader Hellenistic story.38 But Rome’s early history commenced on shaky ground. The invasion by Gauls in 390 BCE and the fire that followed it left much of the city and its records in ruins. The vacuum let in falsehoods which made their way sometimes innocently, sometimes deliberately, into its founding story. Good examples of the latter are the formative speeches in Livy’s Ab Urbe Condita Libri, literally Chapters from the Founding of the City, better known today as The Early History of Rome.39

In his Lectures on The Philosophy of History, first published in 1837, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831) termed this a ‘reflective history’ (as opposed to ‘original’ or ‘philosophic’ history), noting Livy ‘… puts into the mouths of the old Roman kings, consuls and generals, such orations as would be delivered by an accomplished advocate of the Livian era, and which strikingly contrast with the genuine traditions of Roman antiquity.’40 It reminds us that narrative history is a personal philosophy of the past and will always be a ‘child of its time’.41 In an attempt to justify his dialogue with the past and even a republic he did not know, Livy, who ‘praised and plundered’ Polybius’ books along the way, explained that: ‘By intermingling human actions with divine they may confer a more august dignity on the origins of states.’42 He nevertheless admitted the challenge he faced:

The traditions of what happened prior to the foundation of the City or whilst it was being built, are more fitted to adorn the creations of the poet than the authentic records of the historian… The subject matter is enveloped in obscurity; partly from its great antiquity, like remote objects which are hardly discernible through the vastness of the distance; partly owing to the fact that written records, which form the only trustworthy memorials of events, were in those times few and scanty, and even what did exist in the pontifical commentaries and public and private archives nearly all perished in the conflagration of the City.43

Macaulay agreed that the chronicles to which Livy, amongst others, had access were filled with ‘… battles that were never fought, and Consuls that were never inaugurated… such, or nearly such, appears to have been the process by which the lost ballad-poetry of Rome was transformed into history. There was an earlier Latin literature, a literature truly Latin, which has wholly perished, which had indeed almost wholly perished long before those whom we are in the habit of regarding as the greatest Latin writers were born.’44

The earlier historians of Rome had more often than not appeared on the fasti, the list of city magistrates. These were the wealthy elite, a point that supports the contention by Malthus’ 1798 An Essay on the Principle of Population that ‘… the histories of mankind that we possess are – in general – histories only of the higher classes’, though the unfortunate woes of those below are inevitably exposed in passing.45 If the accounts of the past do indeed revolve around the higher social strata, then historians have a dilemma, for: ‘the upper current of society presents no criterion by which we can judge the direction in which the undercurrent flows.’ So the perfect historian, according to Macaulay, is one who ‘… shows us the court, the camp, and the senate. But he shows us also the nation…’ so that ‘… many truths, too, would be learned, which can be learned in no other manner.’46 But they were few and far between. As far as Ammianus Marcellinus’ retrospective view was concerned, the deeds of the Roman plebeian were in any case ‘… nothing except riots and taverns and other similar vulgarities… it prevents anything memorable or serious from being done in Rome.’47 Perhaps Marcellinus, himself a soldier in imperial service, should have questioned why there were riots in the first place, for he might have revealed a cause of the empire’s steady decline.48

These early republican historians, nevertheless, had advantages the later annalists did not: before imperial edicts closed them to public eyes, public records provided a first-hand account of events, for the Annales Maximi of the Pontifex Maximus, the Commentarii of the censors, and the Libri Augurales too had all been available to consult.49 One of the outcomes was the avowed later use of the so-called Libri Lintei, Linen Rolls supposedly kept in the Temple of Juno Moneta, a doubtful documentary source supposedly consulted by the historian Licinius Macer (died 66 BCE) when nothing else was at hand.50

But Rome needed a heroic start in ink, and lacking the pedigree of the great cities of Greece, Augustus finally commissioned a founding epic from Virgil in the style of Ennius (who wrote in the hexameters of Homer) and Naevius (ca. 270-201 BCE). The result was the Aeneid which firmly root-grafted a Roman legendary past to Homer’s heroes of Troy, a heritage reinforced in Dionysius of Halicarnassus’ Roman Antiquities, also written in Augustus’ reign.51 According to Timaeus, the sacrifice of the October Horse at the Campus Martius in Rome was a commemoration of the Trojan Horse itself.52

The Mykonos Vase: a decorated storage container, pithos, and the earliest object known to depict the Trojan Horse from Homer’s Iliad though the warriors wear the panoply of the later hoplite age. Found on the island of Mykonos in 1961 it dates to ca. 670 BCE and it resides today in the island’s archaeological museum.

By the time the private Roman collectors who were interested in Greek and Macedonian affairs got their hands on the papyri containing the earlier accounts, much had already decrepitated. These antique seeds, rotting on a classical literary compost heap, did however fertilise new Roman rootstock, and in that grafted form the genes of some of them survived. Classicus scriptor, non proletarius, an expression first seen in Aulus Gellius’ 2nd century Attic Nights (social standing was being linked to the quality of writing in the phrase) came to represent the works of a distinguished group of authors (writing in Greek or Latin) who were considered meritorious in Rome, and it was those that were destined to be copied, distributed and preserved; or, in the case of the Alexander biographies, given a Roman overhaul.53

In Macaulay’s view, ‘new’ Roman output could not compare to Greek output of ‘old’ and he was scathing about what emerged after:

The Latin literature which has come down to us… consists almost exclusively of works fashioned on Greek models. The Latin metres, heroic, elegiac, lyric, and dramatic, are of Greek origin. The best Latin epic poetry is the feeble echo of the Iliad and Odyssey. The best Latin eclogues are imitations of Theocritus. The plan of the most finished didactic poem in the Latin tongue was taken from Hesiod. The Latin tragedies are bad copies of the masterpieces of Sophocles and Euripides. The Latin philosophy was borrowed, without alteration, from the Portico and the Academy; and the great Latin orators constantly proposed to themselves as patterns the speeches of Demosthenes and Lysias.54

Macaulay additionally reminded us that for ‘modern’ scholars ‘… the centuries which separated Plutarch from Thucydides seemed as nothing to men who lived in an age so remote.’55 Temporal gulfs aside, in the case of the Greeks and Romans it was their literary output, perhaps above anything else, that gave them the sense of self-identity that the barbarians pressing on their borders always lacked. So the wholesale loss of Greek and Hellenistic literature must have been incomprehensible to the scholars of the stalwart Roman Empire.

Rome did her fair share of literary damage; the Senate and Caesar had comprehensively inflamed the keepers and the contents of the libraries in Carthage and Alexandria. Although an unrepentant arsonist, Rome did become the most enduring beneficiary of Alexander’s sweat, blood and ichor, his immortal blood.56 Alexander’s reception in the Eternal City, however, was something of a mixed one; whilst Rome displayed respect for the scale of the Macedonian conquests – they had after all paved the way for her own Eastern Empire – that appreciation was tainted by the ‘filial forbearance, which educated Romans showed towards Greece in her childish and petulant decline’.57

A reconstruction of Carthage at the height of its power in the Punic Wars showing the circular Kothon, the military inner harbour in which up to 220 ships could be moored. The merchant harbour is in the foreground. The entrance could be entirely closed off with iron chains. Image from Rome II © The Creative Assembly Limited – under Licence by the Creative Assembly Limited.

‘PERSUASION HAS NO SHRINE BUT ELOQUENT SPEECH’ 58

… whence and how

Found’st thou escape from servitude to sophists,

Their dreams and vanities: how didst thou loose

The bonds of trickery and specious craft?59

A damaging process had already been at work on the legacy of Alexander before Roman-era authors added their contemplations to the subject. Modern scholars bemoan, as did Polybius, that since the 4th century BCE, history had become the servant of rhetoric, the ‘science of speaking well’, according to Quintilian. The power of artful speech had been appreciated as a political tool as far back as Hesiod’s Theogonia when a king’s persuasiveness was portrayed as a gift of the Muses: ‘Upon his tongue they shed sweet dew, and honeyed words flow from his mouth.’60

Hesiod had visited Delphi and had been shown the Omphalos, the sacred stone that assisted communication with the immortals. Possibly because of that he went on to receive posthumous good fortune, for in the Certamen Homeri et Hesiodi (The Contest of Hesiod and Homer, ‘the poets who gave the Hellenes their gods’),61 a narrative now traceable to the 4th century BCE and the Delian festival in honour of Apollo, it is Hesiod who takes the literary prize ahead of the father of the Trojan epics.62 He might have believed that his victory was due to his instruction by the Muses in the pastures of Mount Helicon, but these were the same Muses that explained to him: ‘We know how to tell many falsehoods which are like truths, but we know also how to utter the truth when we wish.’63

The pejoratives associated with ‘artful speech’, as the Muses hinted, remind us that it involved a less than clinical approach to capturing the facts. The writers of the period had a utilitarian view of history itself, considering their overriding responsibility to be the edification of the reader, or to eristic argument.64

As for history – the witness of the ages, the light of truth, the life of memory, the teacher of life, the messenger of the past – with what voice other than the orator’s can it be entrusted to immortality?65

As witnessed by this extract from De Oratore, Cicero believed orators alone should be entrusted with the past, and he outlined a series of noble tenets on how it should be recorded: ‘The first is not daring to say anything false, and the second is not refraining from saying anything that is true. There should be no suggestion of suspicion of prejudice for, or bias against, when you write.’66 Cicero was a trained rhetorician who assumed imperial posts, and he knew his noble tenet was asking too much of the day.67 But, as pointed out to Cicero by his friend, Titus Pomponius Atticus, ‘it is the privilege of rhetoricians to exceed the truth of history’, a point of view the austere Brutus strongly objected to.68 Cicero, no angel of method, further admitted that, ‘unchanging consistency of standpoint has never been considered a virtue in great statesmen’;69 it was a damaging hypocrisy, if it was not espoused satirically, but presented so eloquently, who could object? And who can deny that the artistic flumine orationis of Demosthenes, Aeschines and Isocrates, or Cicero’s powerful use of tricolons, framed some of history’s greatest oils?70

Elsewhere, Cicero praised plain speaking and likened the rhetorical overlay to ‘curling irons’ (calamistra) on a narrative, further remarking that: ‘All the great fourth century orators had attended Isocrates’ school, the villain who ruined fourth century historiography.’71 Unsurprisingly then, that when he branded Herodotus from Halicarnassus ‘the father of history’, he also bracketed him alongside Theopompus as one of the innumerabiles fabulae, the band of notorious liars.72 Alexander was the century’s greatest son, and his story was bound to come under the influence of the rhetorical ‘whetstone’, as Isocrates described himself.73 So there emerged ‘a sort of tragic history’ that merged rhetorical narrative and tragic poetry together, a result that describes reasonably well the Roman Vulgate genre on Alexander.74

We can only touch lightly on a topic that is deep and without conclusion, for neither Cicero nor Marcus Antonius (died 87 BCE, grandfather of the Triumvir better known today as Mark Antony) finished their treatises on an art that encompassed what Ennius termed ‘the marrow of persuasion’, suada.75 Rhetoric is embedded in the nature of a man and his desire to throw his persuasive cloak over another under ‘the systemisation of natural eloquence’.76 Diodorus even suggested that the Egyptians had long been fearful of the influence of such honey-coated speeches in legal proceedings so everything was conducted in writing in court; later papyri fragments suggest the Ptolemies maintained a sophisticated paper trail of written testimony through court clerks and scribes, as a legacy of that:

For in that case there would be the least chance that gifted speakers would have an advantage over the slower, or the well-practised over the inexperienced… for they knew that the clever devices of orators, the cunning witchery of their delivery… at any rate they were aware that men who are highly respected as judges are often carried away by the eloquence of the advocates, either because they are deceived, or because they are won over by the speaker’s charm…77

Timaeus claimed Syracuse in Sicily as the birthplace of rhetoric.78 So its floruit in Athens was more of a ‘categorisation awakening’ than a beginning, and it brought with it a new appreciation of its method and application. There was never a protos heuretes, a single inventor of the art, as the wide corpus of recommended reading in Dionysius’ De Imitatione suggests, for its development was firmly rooted in pre-history and Greece’s Homeric past.79 Homer provided us with a vivid image of Odysseus’ skill with words: ‘snowflakes in a blizzard’, and Phoenix, the tutor to Achilles, encouraged him to ‘… be both a speaker of words as well as a doer of deeds.’80 Here in the Iliad the power of discourse, psychagogia, was being recognised, and it was thought to persuade souls to take the direction of the truth.81

The etymology of rhetorike was formed from rhetor – typically describing a speaker in a court or assembly – and ike, linking it to art or skill, and the compound of the two was possibly first seen in Plato’s Gorgias. Aristotle claimed Empedocles (ca. 490-430 BCE) had developed an ‘art’ that was already expressed in the Greek logon technai, the ‘skills of speeches’,82 and, according to Cicero, the first manual was written by a Sicilian Greek, Corax of Syracuse, in the 5th century BCE.83 Gorgias of Leontini (ca. 485-380 BCE), ‘the father of sophistry’ (the skillful use of false but persuasive arguments, often employed to present the merits of both sides of a case) of and paradoxologia (‘nihilism’ according to some commentators) ferried it to Athens where Tisias and Antiphon dragged rhetoric and sophistry into the Areopagus or the boule (citizen council) when pitting individual rights against the legal code. With them there did, indeed, appear dissoi logoi, the ‘arguments on both sides’.84

The great Isocrates and Protagoras (ca. 490-420 BCE) ‘clarified’ truth in the streets as well as in the courts for fees previously unheard of, for logographers (speechwriters) were extremely well paid ‘to make the weaker argument stronger’, ton hetto logon kreitto poiein.85 Protagoras is said to have charged 10,000 drachmas per pupil for a single course in his sophistry; its value was no doubt persuasively justified with ‘man is the measure of all things’.86 Ironically, at that time, On Nature by Anaxagoras (ca. 510-428 BCE), a revolutionary book full of groundbreaking cosmic theories (including the impiety that the sun was a ball of fire), could be purchased for just one drachma in the street.87

With no public prosecutor’s office in Athens, individuals had to resort to private suits (dike) and self-funded public suits (graphe) to bring charges. Once their speeches had been written, gifted speakers were sought to deliver the desired result, for witnesses were not cross-examined, jurors were often ignorant of the law, and speakers were restricted in delivery time under the watch of a klepsydra, the judicial water clock. Paradoxically, whilst mendacity detected in speeches given at the boule or assembly was punishable by death, court case perjury remained risk-free, encouraging the subordination of ‘fact’ to deimotes, a ‘forcefulness’ of style.88

Isocrates protected the intellectual property of his teachings at his newly opened rhetorical school by penning Against the Sophists in which he claimed it is impossible to write a handbook on the subject,89 and within two generations of its first public appearance in Athens, rhetoric was endemic to debate, whether legal or historical. Timon summed it up: ‘Protagoras, all mankind’s epitome, Cunning, I trow, to war with words.’90 The ‘cunning’ was a verbal mageia, a word first recorded by Gorgias in his Encomium of Helen: ‘The power of speech over the disposition of the soul is like the disposition of drugs… by means of some harmful persuasion, words can bewitch and thoroughly cast a spell…’91

By Alexander’s day, the Akademia had been drawn in. Aristotle launched his Gryllos on Isocrates, prompting a riposte from Cephisodorus, and there followed detailed polemics from both sides: the Protreptikos and the Antidosis. Rhetoric was being vitiated by rhetoric to the detriment of literature in general, and as Aristotle argued, fine language was being disarmed by fine argument, skills that Demosthenes and Aeschines were to refine. Demosthenes had been aided by lessons from actors, by speaking with a mouth full of pebbles, from long nights rehearsing (his arguments were labelled as ‘smelling of lamp wicks’),92 and according to Aeschines, by fancy footwork as well.93 When the great logographos was asked for the most important element in his craft, Demosthenes artfully replied ‘only three things count, delivery, delivery and again, delivery’, so Quintilian claimed.94

Isocrates and the Ten Attic Orators had much to answer for in Athens, because the political and forensic show-speeches, along with the declamations we encounter throughout classical works, were originally crafted here. Demosthenes, Aeschines, Hyperides, Lycurgus and Deinarchus (ca. 361-291 BCE) all had something to say about Philip and Alexander, as well as their successors, and none of it was straight talk. Some of them called themselves ‘philosophers’, a term Pythagoras is said to have invented; it was a label described by Cicero as a ‘lover of wisdom and spectator of the universe, with no motive or profit or gain.’95 That popular claim appears spurious, however, and is challenged as an invention of the Platonist school; the origins of the compound word, ‘philosopher’, were perhaps inspired by Aristophanes’ Thinkery in Clouds, with its farcical treatment of Socrates. In fact Herodotus suggested Croesus came close to the definition of a philosophos in his famous greeting to the Athenian sage and lawgiver, Solon, at Sardis ca. 560s BCE, if the episode is historic.96

A Roman marble herm of Demosthenes inspired by the bronze statue by Polyeuctus, ca. 280 BCE. Now in the Louvre in the Department of Greek, Etruscan and Roman Antiquities.

Lucian said of street ‘philosophers’ in general that their ‘argument is turned upside down, they forget what they are trying to prove, and finally go off abusing one another and brushing the sweat from their brows; victory rests with him who can show the boldest front and the loudest voice, and hold his ground the longest’; the ‘butcher’s meat’ of fact was being garnished ‘with the sauce of their words’.97 Their arguments, however, when preserved with an attached epistolary corpus, are useful indicators of the social currents of the day, but their influence on literature meant epideictic rhetoric fleshed out what might have once been leaner and untainted accounts, so that they now require bariatric surgery under Quellenforschung’s knife to get to the internal organ of fact.98 Whichever way it is bottled, the tumult of rhetoric was drowning out the simpler tones of truth, as the Peripatetic school at Athens was soon vocally pointing out.99

The Lyceum (unearthed in Athens in 1996) and later the Academy churned out manuals which loved to classify, a predisposition taken from Pythagoras. Aristotle quickly had rhetoric hung, drawn, and systematically quartered into a sunagoge technon, a collection of methods (in defiance of Isocrates’ claim) and he then did the same to sophistry.100 When he inherited the subject from Plato, who viewed it as the ‘art of enchanting the soul’,101 he concluded: ‘In the case of rhetoric, there was much old material to hand, but in the case of logic, we had absolutely nothing at all, until we had spent a long time in laborious investigation.’102 Not to be outdone by Plato’s six species, Aristotle saw four uses for the art (panegyric, encomium, funeral oration and invective), with three modes of persuasion and four lines of argument under five main headings for use in the seven courses of human action, discounting the subheadings. Plato didn’t thank Aristotle for being ‘out-classified’ for the Platonists despised kainotomia, innovation; he soon termed him the ‘the foal’, presumably because, as Diogenes Laertius tells us, Plato said of his pupil’s secession, ‘Aristotle has kicked us off…’103

CETERUM CENSEO CARTHAGINEM ESSE DELENDAM

In Rome, the newly imported seductive oratorial arts, and the attendant new philosophies, were not universally accepted, and neither was Greece itself. The sapient Cato the Elder (234-149 BCE, also known as ‘Cato the Censor’), who started life as a rigid Sabine farmer, warned his son:

I shall explain what I found out in Athens about these Graeci, and demonstrate what advantage there may be in looking into their writings (while not taking them too seriously). They are a worthless and unruly tribe. Take this as a prophecy: when those folk give us their writings, they will corrupt everything.104

Cato did, nevertheless, appreciate the practical advantages of rhetoric; something of an antilogy.105 In 181 BCE, newly unearthed Pythagorean manuscripts of Numa Pompilius, the legendary second king of Rome (who supposedly reigned 715-673 BCE), were burned in the forum (they were in any case frauds) for containing unsuitable Greek doctrine (‘subversive of religion’), and Cato went on to warn of Greek doctors that they were ‘sworn to kill all barbarians with medicine…’106 In this censorious environment, the comedies of the home-grown playwright, Plautus (ca. 254-184 BCE), released between 205 and 184 BCE, stood little chance of being aired. There were no permanent theatres in Rome, possibly because drama was still considered a corrupting influence too (no doubt due to its Greek heritage), and it wasn’t until 55 BCE that Pompey (‘the Great’) opened his theatre in the Campus Martius, inspired by a visit a few years earlier to Greek Mytilene.

Clearly xenophobic and a master of invective, Cato fought with distinction in the campaigns against Hannibal in the Second Punic War. It was an experience that furnished him with a call for a rerum repetitio when ending his senatorial orations: ‘ceterum censeo Carthaginem esse delendam’ – ‘furthermore, I maintain that Carthage should be destroyed’. Cato’s rigid virtue would have gladly hurled a spear dipped in blood across the Carthaginian border, whilst the Hellenism of sophisticated and distinguished Roman families continued to offend him.107 They included the gens of Scipio Africanus to whom he remained firmly opposed. Unsurprisingly, a collection of widely read pithy and conservative maxims, the Disticha Catonis, was falsely attached to the brooding censor.108

Cato supported the Lex Oppia (Oppian Law) which restricted women to wearing no more than half-an-ounce of gold adornment as an austerity measure in the troubled days following Hannibal’s victory at Cannae (216 BCE). Rome itself was lucky to avoid an assault, and the two suffetes of Carthage and the Tribunal of One Hundred and Four must have demanded why the Carthaginian general failed to attack the city immediately after;109 some 50,000 Roman soldiers had died in the battle and the path to the gates lay relatively undefended.110 Cato additionally advocated the Lex Orchai, which limited guests at an entertainment, and the Lex Voconia, designed to check the amount of wealth falling in the hands of women. This inspired Livy to wholly construct a speech in which Cato entreated husbands to control their errant wives.111 Though Cato’s invective contributed to the eventual fall of Carthage, the result saw such great wealth arriving in Rome that it forced the repeal of the unpopular laws following street protests by women. The newly arriving funds did, however, justify Cato’s adage, bellum se ipsum alet: ‘war feeds itself’.

The Macedonian Alexander, an ‘orientalist’ who fell into the barbarian trappings of the Persian Great Kings, was not a figure to be rolled out at banquets in the presence of the censor. Cato had also fought at Thermopylae in 191 BCE thwarting the invasion of Antiochus III; it was a battle that ended Seleucid influence in Greece and suffocated the last gasps of Alexander’s Diadokhoi. In the same year Cato gave a speech in Athens and he conspicuously delivered it in Latin although he spoke Greek.112 He was a redoubt that for an influential time threw back many cultural imports, and it has even been proposed that his Latin works were instrumental in halting Greek from becoming the dominant language in Rome. Yet Cato’s Origines (of Italian towns) in which Lucius Valerius had reminded him that he had emphasised the role of women in the founding of the city, and his rustic De Agri Cultura (On Farming) could not distract the populace from finally turning their heads to the more exotic and seductive themes of the Hellenistic Age.

GRAECIA CAPTA FERUM VICTOREM CEPIT ET ARTES INTULIT AGRESTI LATIO113

Cato blamed the campaign against Macedonia in 168 BCE for importing more Greek moral laxity into Rome, claiming, ‘… the surest sign of deterioration in the Republic [is] when pretty boys fetch more than fields, and jars of caviar more than ploughmen.’114 His austerity continued to prevail, for a while, and in 161 BCE rhetoricians were expelled from the city. Some seven years earlier the still-circulating Alexander-styled currency had also been banned.115 But in 155 BCE Athens impressed Rome with a ‘philosophical embassy’ sent to argue for the repeal of a 500 talent fine; it included the Stoic, Diogenes of Babylon (ca. 230-145 BCE), the Peripatetic, Critolaus (ca. 200-118 BCE), and the Sceptic, Carneades (214-129 BCE). Between them they disarmed all opposition by the magic of their eloquence so that the youth of the city flocked to hear them plead their case and became immediately ‘possessed’.116

Although Cato, now almost eighty, arranged their speedy departure, the door to new ideas had been irreversibly opened and soon ‘Rome went to school with the Greeks’.117 When the official philosophical schools at Athens were closed in 88 BCE by edict of the Roman Senate,118 Greece experienced a ‘brain drain’ as philosophers and rhetoricians journeyed west to become ‘household philosophers’ in Rome, though whether they too inscribed Probis pateo – ‘I am open for honest people’ (inscribed on city gates and on entrances to schools) – above the door is debatable.119 And with them arrived the topic of Alexander on a tide of new philosophical doctrines and their associated ‘wisdoms’.

The Attic style of epideictic flourished elsewhere, in Rhodes for example, where it perpetuated the tradition until Apollonius Molon settled on the island and taught Caesar and Cicero to orate.120 As Lucian imagined it in the cultured centres, there were ‘everywhere philosophers, long-bearded, book in hand… the public walks are filled with their contending hosts, and every man of them calls Virtue his nurse… these ready-made philosophers, carpenters once or cobblers.’121 But ‘Virtue lives very far off, and the way to her is long and steep and rough…’,122 and so we can only speculate on the quality and experience of the ‘beards’ arriving from Greece.

The Hellenistic era had witnessed the emergence of the philosophical schools of the Kynikoi, Stoikoi, Skeptikoi and the happier followers of Epicurus at the expense of the Academy and Lyceum of Plato and Aristotle, as thinkers tried to rationalise a radically changing world, or, as Epicurus espoused, withdraw from it, for he suffered from perennial bad health. Inevitably, Alexander became the perfect canvas on which to project their new ideas for Roman contemplation; the Macedonian king was used as an exemplum and his life a propaedeutic to a full-blown syllabus on rhetoric and in the process he became a punch-bag for a Roman conscience being newly tested by its own aggressive expansion in the East. As one scholar put it, Alexander was ‘… both a positive paradigm of military success and a negative paradigm of immoral excess, of virtus and vitia in a single classroom incantation.’123

Despite a further castigation of rhetoricians in Rome enacted in 92 BCE by the censors in an effort to stem their influence in the Senate,124 a manual on rhetoric from the articulate politician Marcus Antonius had appeared sometime between in the decade before, though the still anonymous Rhetorica ad Herennium may have been the first Latin manual on the subject, a possible remodel the Rhetorica ad Alexandrum once attributed to Aristotle.125 Cicero’s De Inventione Rhetorica was published when he was still an adolescent (likely in 88-87 BCE), his De Oratore followed (55-46 BCE?), and soon after his Partitione Oratoriae and his Brutus Or A History of Famous Orators.

The bust of Cicero at the Capitoline Museum, Rome

But by then free speech was dying in Rome; Cicero’s manuals could not be fully exploited when civil wars threatened and proscription lists appeared, and his De Optimo Genere Oratorum was only published posthumously.126 Some rhetors like Potamon of Mytilene, a renowned expert on Alexander, soon enjoyed the patronage of the Roman emperors, in this case Tiberius. Yet even for that notoriety, Potamon’s works, including On the Perfect Orator, did not survive.127 Finally, funded by a salary from the Privy Purse, Quintilian’s twelve-book Institute of Oratory (written through 93-95 CE) and Tacitus’ Dialogue on Orators emerged; Romans had finally ‘submitted to the pretensions of a race they despised’.128 So there appeared the claim from Horace: ‘Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit et artes intulit agresti Latio’ – ‘Captive Greece conquered its fierce conqueror and civilised the peasant Latins.’ Virgil had been right to warn of Greeks bearing gifts.129

THE RETURN OF THE RHETORICAL SON

When searching for the remains of the original Alexander, we have to deal with the realities of historians living within the literary Pax Romana (‘absolutism as the price for peaceful order’) for censorship was tangible and authors were fair game.130 Precedents had been set and the sound of Praetorian Guards marching into the atrium was never difficult to imagine, and neither was the drifting stench of the Tullianum, Rome’s notorious prison. If we detect Livy himself was attached to the idea of a Republic, he never quite told that to his emperor, Augustus, who had by then suppressed publication of the Acta Senatus, the official records of senatorial debates at the dawn of the Principate.131 Livy, ‘peculiarly Roman’ with ‘a hundred kings below him, and only the gods above him’, had by now published much of his monumental 142-book Ab Urbe Condita Libri.132 He was given the young Claudius to tutor and sweetened his history lessons by suggesting the Macedonians ‘had degenerated into Syrians, Parthians and Egyptians’ when referring to the Hellenistic kingdoms of Alexander’s successors.133

It seems that there was still sensitivity to the lingering power of the Diadokhoi-founded dynasties in the wake of the self-serving propaganda of Octavian which held that ‘the last of the Ptolemaic dynasty was threatening to hold sway in Rome itself’; that is, with the help of Mark Antony who fell under the spell of Cleopatra.134 Livy, who commenced his long work when Diodorus (broadly) ended his, felt he needed to defend Rome from insinuations that she would have fallen to the Macedones:135

Anyone who considers these factors either separately or in combination will easily see that as the Roman Empire proved invincible against other kings and nations, so it would have proved invincible against Alexander… The aspect of Italy would have struck him as very different from the India which he traversed in drunken revelry with an intoxicated army; he would have seen in the passes of Apulia and the mountains of Lucania the traces of the recent disaster which befell his house when his uncle Alexander, King of Epirus, perished.136

Livy, Lucan (39-65 CE), Cicero, and the stoical Seneca, managed to frame Alexander as an example of moral turpitude when highlighting the depravity of absolute power, and their Epistulae Morales and Suasoriae (persuasive speeches) flowed. Arrogance and false pride were the two principal vices of Stoic doctrine and the opening pages of Seneca’s On the Shortness of Life could be an unfriendly dedication to Alexander, with its rejection of insatiable greed and political ambition, the squandering of wealth and the foolhardiness of inflicting dangers on others. In the case of Seneca, a tutor to young Nero, the Alexander-Aristotle relationship was clearly being relived. Lucan’s De Bello civili, better known as Pharsalia and treading dangerous polemical ground under Nero, termed Alexander ‘the madman offspring of Philip, the famed Pellan robber’; he was further described as nothing short of mankind’s ‘star of evil fate’. Lucan added: ‘He rushed through the peoples of Asia leaving human carnage in his wake, and plunged the sword into the heart of every nation.’137

Seneca took at face value Trogus’ claim (preserved by Justin) that Alexander caged Lysimachus with a lion as a punishment for his pitying Callisthenes; he had allegedly handed poison to the caged historian to end his suffering.138 It was useful as a character defamation and yet Curtius clearly stated the report was nothing but a scandal; moreover, this Lysimachus was likely Alexander’s Arcanian tutor and not the Somatophylake who inherited Thrace.139 Seneca likewise accepted the ill-fated quip made by the Rhodian, Telesphorus, about Lysimachus’ wife, Arsinoe (the daughter of Ptolemy by Berenice), along with his subsequent mutilation at Lysimachus’ hand.140 Athenaeus had read no evidence of mutilation and Plutarch credited the remark to Timagenes.141 Neither episode was challenged, for each provided the perfect dish for a polemic on the corruption of kings and tyrants.

Alexander’s deeds inspired the republican iconoclasts to vilify him publicly and the city’s first men to emulate him privately; in Valerius Maximus’ nine books of Memorable Deeds and Sayings (published sometime under Tiberius) the Macedonian king appears at the centre of the frequent exempla on behaviour encompassing both virtues and vices, suggesting a transition was in progress.142 And despite their thunderous tirades and the continuous cloud-cover of the earlier Greek invective, the rays of grudging admiration managed to shine through.

As unbridled power manifested itself ever more comfortably through dictators in Rome, and as independent power was stripped from the comitia, the concilium, the plebeian tribune, and finally from the Senate, the diluted conscience of the Roman republic was more easily assuaged. When apotheosis was finally muttered and Eastern campaigns planned, Alexander emerged once more into the sunlight of imperial emulation when philhellenism returned to fashion, a somewhat ironic result in light of Macedonia’s own suppression of Greek freedom.143 Finally, emperors embraced Alexander in earnest, portraying him as a giant who turned the course of Hellenic history and ultimately that of Rome. They besieged his name, stormed his historical pages and inhabited the very footsteps he walked in.

Pompey, who shared the epithet invictus (‘unconquered’) with Scipio and Alexander,144 and then Julius Caesar, Augustus, Caligula, Nero, Trajan, Marcus Aurelius (ruled 198-211 CE), Caracalla and Septimus Severus (145-211 CE) who locked up the Alexandrian tomb to deny anyone else a glimpse of Alexander’s corpse, all felt the need to stylise themselves on the Macedonian conqueror in some way. Even Crassus believed he was treading in his footsteps en route to his disastrous invasion of Parthia, and probably Mark Antony did too, with similar calamitous results. Like Alexander, they managed to attach themselves to Heracles and Dionysus, but unlike the Macedonian, neither made it to India where the divine hero and god ‘civilised’ and procreated.145

Septimus Severus is even said (perhaps spuriously) to have reconstituted a Silver Shields brigade in emulation of the elite Macedonian hypaspist corps (mobile infantry, used on special missions). Caracalla, who named his officers after Alexander’s generals, demanded the title ‘Great’, and he even took the name ‘Alexander’ after inspecting his body in its tomb in Alexandria; he deposited his own cloak, belt and jewellery, we are told, in return for Alexander’s drinking cups and weapons.146 Caracalla is said to have persecuted philosophers of the Aristotelian school based on the lingering Vulgate tradition that Aristotle had provided the poison that killed the Macedonian king (T9, T10).147

Alexander, with his unique dunasteia (broadly, his aristocratic house, thus ‘dynasty’), was now being subsumed into the essence of Rome; Gore Vidal said of the emperors: ‘The unifying Leitmotiv in these lives is Alexander the Great.’148 A century and a half ago Nietzsche encapsulated their historical perspective, reminding us why we need to reconstitute Alexander without the Roman-era additives:

Should we not make new for ourselves what is old and find ourselves in it? Should we not have the right to breathe our own soul into this dead body? Being Roman they saw it is as an incentive for a Roman conquest. Not only did one omit what was historical; one also added allusions to the present and not with any sense of theft but with the very best conscience of the imperium Romanum.149

In this environment it was inevitable that a new wave of historians felt compelled to reconstruct the story of the Argead king.

A marble bust of Caracalla by Bartolomeo Cavaceppi (ca. 1750-70) based on a likeness in the Farnese collection in Rome and then Naples, believed to date from the 200s CE. In planning his invasion of the Parthian Empire, Caracalla equipped 16,000 Macedonians as a traditional phalanx despite the fact that it was by now an obsolete tactical formation. They were armed as ‘in Alexander’s day’ with ‘helmet of raw ox-hide, a three-ply linen breastplate, a bronze shield, long pike, short spear, high boots, and sword’. Unless this refers to other brigades outside the traditionally outfitted pezhetairoi, this description is challenging.150

THE EXTANT SOURCES – ‘SECONDARY’ AT BEST

The Roman-era writers who ‘preserved’ Alexander’s history inevitably bemoaned the archaic unreliability of their Graeci literary ancestors, in the same way the historians of Hellas had been critical of their forerunners. Quintilian perhaps epitomised the Roman arrogance when he ranked Sallust beside Thucydides, comparing Livy with Herodotus and Cicero to Demosthenes, though he conceded in the process that the Greeks had provided the models for Rome’s own literary achievements. Cicero himself had once hailed the orator Lucius Licinius Crassus (140-91 BCE) as the ‘Roman-Demosthenes’, yet that was a politically astute encomium for a mentor who became a powerfully wedded consul.151

But the biggest Roman-era historiographical disservice was not to name their sources at all. Even when considered worth preserving, the literary forerunners were, more often than not, publicly assassinated, quietly assimilated and destined to servitude as an anonymous section in voluminous Bibliotheke or a series of biographical Vitae. Moreover, any methodology for working with sources remained a highly personalised affair.

Arrian announced a basic and instinctive form of Quellenforschung with: ‘Wherever Ptolemy and Aristobulus in their histories of Alexander, the son of Philip, have given the same account, I have followed it on the assumption of its accuracy; where their facts differ I have chosen what I feel to be the more probable and worthy of telling.’152 But did Arrian appreciate the responsibility that came with the statement? For the version he selected stuck and all else has vanished for eternity, for: ‘Every history written elbows out one which might have been.’153 His approach was surely an emulation of Xenophon who voiced the same sentiment in his Hellenika, which, rather than a history of Greece, reads more like a book of prejudiced memoirs written for ‘those in the know’ (it was hostile to Thebes, in particular, for her ascendancy over Sparta).154 If Arrian unconsciously let the nostalgia of the Second Sophistic slant his prose, and recalling that his primary sources had been politically intriguing, then both conscious and unconscious processes were at work on Alexander.

The result of these unconscious processes: ‘All history is contemporary history, the re-enactment of past experience relevant to the present’,155 and as far as a historian, modern or from the classical past, ‘…time sticks to his thinking like soil to a gardener’s spade’.156 So ‘a fully objective critique’ of history is impossible, as a Horizontverschmelzung, a ‘fused horizon’, blinds interpretation with a ‘historically effected consciousness’.157 In other words, the Roman-era historians re-rendered Alexander in their own philosophies and words. Although individual ideology was not subject to state control (though clearly it was threatened by it), the wider biases of class, value, and culture were as prominent then as today. It is against this backdrop that the extant accounts of Diodorus, Justin, Curtius, Plutarch and Arrian were written under successive Roman dictators and emperors. Their information could not have been better than that they had inherited, though perhaps they thought otherwise, and at this point Rome was not devoid of primary and intermediary sources that had documented the era (in contrast to the period post-Ipsus), as evidenced by the many contributing historians named in Plutarch’s accounts.158

Arrian explained his particular motivation for tackling the subject: no extant Alexander history appeared to be trustworthy, as a group they conflicted, and no single work captured the detail satisfactorily, to his taste at least: ‘There are other accounts of Alexander’s life – more of them, indeed, and more mutually conflicting than of any other historical character.’ He added that the ‘… transmission of false stories will continue… unless I can put a stop to it in this history of mine.’159 Pearson suggested Arrian’s work was nothing less than a protest against the popularity of Cleitarchus’ ‘unsound history’ which was circulating in Rome.160

But Quellenforschung’s forensic eye is revealing that what have been often termed ‘good’ sources – those behind the so-called ‘court tradition’ of Arrian, for example – include what are now considered deposits of highly dubious material. On the other hand, writers once deemed ‘dubious’ provide us, on occasion, with a core of credible information from genuine lost texts. But identifying where that core separates from the mantle and the crust remains a challenge, so as far as the value of these secondary sources to Alexander’s story: ‘The old custom of dividing their writings into “favourable” and “unfavourable” has now been abandoned for a more sceptical, cautious and nuanced approach.’161 In Peter Green’s opinion, ‘The truth of the matter is that there has never been a “good” or a “bad” source-tradition concerning Alexander, simply testimonia contaminated to a greater or lesser degree, which invariably need evaluating, wherever possible, by external criteria of probability.’ 162

HISTORIA KATA MEROS

The earliest of the five extant writers dealing with the exploits of Alexander, the Greek Sicilian Diodorus, was constructing a ‘universal’ narrative along the lines of Polybius and Ephorus, and with no monographic pretensions towards the Macedonian king. Noting that events ‘lie scattered about in numerous treatises and in divers authors’, Diodorus echoed a rather Polybian case for his thirty years of research and compilation as part of the introduction we cited above:

Most writers have recorded no more than isolated wars waged by a single nation or a single state, and but few have undertaken, beginning with the earliest times and coming down to their own day, to record the events connected with all peoples…163

With less space allocated to the extended didactic speeches we find in Thucydides, for example, and yet clearly influenced by what appears to be Ephorus’ sentiment (derived from Isocrates) on ‘moral utility’, Diodorus once more focused on ‘great men’, and he seems to have scorned democracy with its ‘vast numbers that ruin the work of the government’ in the process.164 Polybius had already commented on Athens’ political system and perhaps set the tone: ‘It naturally begins to be sick of present conditions and next looks out for a master, and having found one very soon hates him again, as the change is manifestly for the worse’,165 a statement that conveniently appears to back-up his anacyclotic model.

In his philosophical introduction, Diodorus informed us that his Bibliotheke Historika covered 1,138 years and was arranged into three distinct sections.166 The first was the ‘mythical’ in which he introduced Greek and Egyptian creation theories and narrated events through to the Trojan War. The second was a compendium of accounts ending at Alexander’s death, and he originally planned the third, the last twenty-three books, to run past the first ‘unofficial’ Roman Triumvirate of 60/59 BCE formed between Julius Caesar, Crassus and Pompey, and through to Caesar’s Gallic Wars of 46/45 BCE. But he ceased at the earlier terminus, though later events were mentioned; the halt was probably prudent considering the danger of commenting on contemporary events during the bloody Second Triumvirate.167 Of his original ‘library’, only books one to five, and eleven to twenty, survive anywhere near intact, though fragments from the remaining sections can be found in the 280 surviving epitomes of Photius.168 Fortunately, Philip II, Alexander and the Successor Wars years under scrutiny, reside in books sixteen to twenty.

Diodorus’ work has been a weapons testing ground for the deployment of Quellenforschung and yet we know little about his life beyond what he himself told us, along with one further reference by the Illyrian Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus (ca. 347-420 CE), otherwise known as St Jerome: ‘Diodorus of Sicily, a writer of Greek history, became illustrious.’169 Diodorus hailed from one of the oldest and formerly wealthiest, and yet now (according to Cicero) one of the most impoverished, settlements in the interior of Sicily, Agyrium, where a surviving tombstone inscription is dedicated to a similar named ‘son of Appollonius’ – we assume the historian. In 36 BCE, in the decade in which Diodorus was likely publishing, Octavian stripped the Sicilians of their Roman citizen rights, Latinitas, previously granted to them by Sextus Pompey.170

Nevertheless, Diodorus afforded Agyrium – which may have suffered as a result of opposing Roman interests in the First Punic War – and its Heraclean cult (Heracles had supposedly visited the town) an importance out of context in the scale of his overall work (Timaeus was accused of much the same); he made ‘events in Sicily finer and more illustrious than those in the rest of the world’.171 Ephorus, too, had repeatedly assured his readers that the population of his home, Cyme in northwest Asia Minor, was ‘at peace’, possibly taking Euripides’ words at face value: ‘The first necessity of a happy life is to be born of a famous city’, and apart from attachments to Homer and Hesiod, Ephorus inferred every Spartan or Persian military action had some strategic link with Cyme.172 So when Diodorus digresses into a Cymian saga we can confidently pinpoint his source.173

Evidence suggests Diodorus’ information gathering took place broadly between 59 BCE and the publication date somewhere between 36-30 BCE, a period in which Roman authority reached ‘to the bounds of the inhabited world’, a state of affairs that concerned him despite his admiration for Rome’s earlier achievements.174 But parts of his first books appear to have circulated earlier, released as a separate packet.175 He seems to have spoken imperfect Latin (though living on Sicily gave him a ‘considerable familiarity’ with the language) and the jury remains out on whether he drew from Latin texts at all for detail on Roman affairs. Like Herodotus, he claimed to have travelled widely in the continents he would have termed ‘Europa’ and ‘Asia’, but at times his geography is just as shaky as Herodotus’, in whose Histories we see the first references to those continental names. It is clear from his eyewitness testimony, however, that he did spend time in Egypt (from ca. 60/59 BCE) and he appears to have consulted the ‘royal records’ in Alexandria before basing himself in Rome (from ca. 46/45 BCE) for a ‘lengthy’ time, though no patrons nor reading circle associates were ever mentioned.176

Admitting he followed ‘subject-system’ subdivisions, Diodorus dealt with the fate of individuals sequentially, separating biographical threads rather than developing them in parallel, a method that complicates our understanding of the chronological progression; the result is at times akin to a ‘kaleidoscopic disjunctiveness’.177 Whilst dubbed ‘universal’ in approach, and indeed at times he was panoramic in his scope, Diodorus all too often provided us with a monographic narrative that Polybius would have termed historia kata meros, history ‘bit by bit’, a definition close to the criticism afforded to Thucydides (only mentioned once in the extant chapters of Polybius) by Dionysius of Halicarnassus, whose books, beside those of Polybius and Diodorus, represent the only surviving works of the Hellenistic era sufficiently intact to be of use to modern historians.178

Diodorus was cutting and pasting ‘the numerous treatise from divers authors’, squeezing them into a highly generalised timeframe, though he was not blind to the shortcomings of his method, as he himself explained:

… it is necessary, for those who record them, to interrupt the narrative and to parcel out different times to simultaneous events contrary to nature, with the result that, although the actual experience of the events contains the truth, yet the written record, deprived of such power, while presenting copies of the events, falls far short of arranging them as they really were.179

Polybius had encountered a similar problem, and Ephorus had preceded Diodorus with this approach: a balancing act of grouping related events together and yet fitting the whole into an annalistic (year by year) framework, earning the Cymian writer Polybius’ praise as the ‘first universal historian’.180 In contrast, Seneca felt: ‘It requires no great effort to strip Ephorus of his authority; he is a mere chronicler.’181 Sempronius Asellio (ca. 198 to post-91 BCE) had already stated the flaw with the annalistic approach: ‘Annals make only known what was done and in which year it was done, just as if someone were writing a diary, which the Greeks call ephemeris. I think that for us it is not enough to say what was done, but also to show for what purpose and for which reason things were done.’182 A more modern interpretation: we get the ‘gleam but no illumination: facts but no humanity’.183

In Diodorus’ chronological progression, Alexander’s achievement sat like a huge boulder – the greatest in history he believed – in the literary road from prehistory to the increasingly turbulent present, and one that could not be split this time with fire and sour wine.184 In his opinion: ‘Alexander accomplished greater deeds than any, not only of kings who lived before him but also of those who were to come later down to our time.’185 And that would have been a slap in the face to the career of Julius Caesar had not Diodorus additionally and expediently stated that Caesar was the historical character he admired the most.186

The chapters focusing on Alexander in Diodorus’ Bibliotheke are considered to be about one-tenth as long as Cleitarchus’ narrative (estimated from scant evidence), whereas Curtius’ biography roughly tracked Cleitarchus’ original length; this uneven abridgement would explain many of the discrepancies within otherwise comparable Vulgate profiles.187 And though a subject of intense debate, it remains easier (though less tantalising) to swallow the idea that the tones and nuances attachable to earlier Hellenistic historians that we see in the Roman-era Vulgate, also came from Cleitarchus, who, publishing in the 370s or 360s BCE, had himself incorporated these influences. The alternative requires us to accept that each Vulgate historian flitted between a number of earlier sources and yet still produced a markedly similar result. Any remaining variation in commentary we see simply reflects the ethnic backgrounds and social climates attachable to the latter-day authors and the varying degrees to which they compressed Cleitarchus’ account.

For details of events that followed Alexander’s death, scholars have reached a ‘somewhat uneasy agreement’ that Diodorus shifted sources to Hieronymus of Cardia, once again with a heavy compression of text.188 Faced with the complete loss of Hieronymus’ original account, the slant of Diodorus’ chapter-opening proemia (prologues, which sometimes, however, conflict with his narrative) and the identification of unique diction may provide a valuable path back to his original sources.189 As examples, idiopragia (‘private power’ rather than ‘mutual gain’) and the technical terms katapeltaphetai (literally ‘catapultists’) and asthippoi (elite cavalry units whose role is still debated) uniquely used by Diodorus to describe episodes we believe Hieronymus had eyewitnessed, act as tell-tales to his presence when we see them reused elsewhere.190 Inevitably, in this shifting of sources at the point of Alexander’s death, there was an overlap in information, and the result was untidy and conflicting with his later narrative.

In his opening proem, Diodorus expressed the fear that future compilers may copy or mutilate his work; perhaps this is suggestive of his own guilty conscience.191 Classical writers frequently regurgitated their sources uncreatively, and Diodorus, the ‘honest plodding Greek’ who adopted a utilitarian and stoical approach, was no exception.192 Termed an uncritical compiler, Diodorus took the path of least resistance in completing the ‘immense labour’ behind his interlocking volumes.193 In 1865 Heinrich Nissen reasoned that Diodorus habitually followed single sources due to the practical difficulties of delving into multiple scrolls for alternative narratives.194 As early as 1670 John Henry Boecler (and later Petrus Wesseling in 1746) determined he had been plagiarising Polybius to a scandalous degree and this was no better illustrated than in his digressions on Fortune.195 It has even been suggested that Diodorus took his information through intermediaries, Agatharchides of Cnidus for example, in an already epitomised form. But there is little proof, and to what extent he did use mittelquellen, middle sources, or showed true independence of thought and opinion, remains sub judice.196

Diodorus’ own declaration of method suggests he was not entirely mechanical and the title of his work, Library of History, was honest to the content, for it suggested nothing more than a collection of available texts,197 which under Hegel’s strict definition, would classify him as a ‘compiler’ not a ‘historian’.198 In a sense this is fortunate and we might thank him for lacking any great gift of originality, for a more personal interpretation might have rendered his Alexander sources unrecognisable, where instead (we believe) we receive a fair impression of Cleitarchus’ underlying account of Alexander, and of Hieronymus’ account of the years that followed. As it has been observed, some ‘universal’ historians were more ‘universal’ than others.199

THE FLORUM CORPUSCULUM: THE PETALS OF EPITOME

We would like to say much about Gnaeus Pompeius Trogus, a Romanised Vocontian Gaul writing ‘in old fashioned elegance’ in the rule of Augustus, and the least possible about Justin, in whose epitomised books Trogus’ cremated ashes are compacted.200 Unfortunately, little remains of Trogus’ original Historiae Philippicae (et totius mundi origines et terrae situs), ‘the only world history written in Latin by a pagan.’201 Justin did however provide useful prologoi or summaries of the contents of each chapter in his Epitoma Historiarum Philippicarum libri XLIV in a similar manner to Trogus himself and the anonymous 4th century Periochae compiler who summarised Livy’s lost books. The problem with epitomes, as Brunt proposed, is that they ‘… reflect the interests of the authors who cite or summarise the lost works as much or more than the characteristics of the works concerned.’202

Within Justin’s précis of Trogus there remains a clear bias in content towards Spain, Gaul (which reportedly sent envoys to Alexander in Babylon), Carthage, and the western provinces of the Roman Empire, understandable for an author born in Gallia Narbonensis, broadly modern Provence. Trogus’ work stretched back to the dawn of time covering the successive great kingdoms in the style of Herodotus, but now extending further forward, through the empires of Assyria, Media, Persia, Macedonia and to Rome with its present Parthian challenge.203 Trogus’ family had made its mark in Rome; his grandfather and uncle served under Pompey the Great, and Trogus claimed his father was some kind of secretary-diplomat to Julius Caesar. This last detail suggests a switched allegiance, for Pompey and Caesar were opponents until the final decisive battle at Pharsalia in June 48 BCE, after which Pompey fled to Egypt and assassination by Pothinus, the eunuch of Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopatros (the ‘father loving God’).204

Of Trogus’ forty-four books, those numbered seven to thirty-three focused on the rise and fall of Macedonia, and six of them on the deeds of first Philip II, and then Alexander. If Ptolemaic Egypt is considered an extension of their influence, then Macedonian dynasties dominated the texts through to book forty. All in all, Philip came off badly, a sine qua non of the late Roman republic: he was the terminator of Greek liberty, though both Polybius and Trogus credited him with laying the foundation stone of Alexander’s success.205

Trogus’ annalistic history did not pander to the audience in Rome whose imperialism is criticised through the device of rhetorical speeches, and Parthia is positioned as the moral heart of the Persian Empire, casting doubts on Roman incursions. Here Fortuna, the new incarnation of the Greek goddess Tyche, played her part in Alexander’s quest to be named king of the world, universum terranum orbem.206 Justin’s epitome suggests Trogus’ original work, though eloquent (sufficiently so for Trogus to have confidently criticised both Livy and Sallust),207 appears to have reinforced the darker themes attached to Alexander, as well as other influences already embedded in Cleitarchus.208 Of course, the closer-to-home exhortations of Roman republican polemic had their effect as well; corruption by wealth is blamed for the downfall of the Lydians, the Greeks, and ultimately, Alexander himself.209

How much of the vocabulary in Justin’s epitome was his rather than Trogus’ remains debatable, though scholars are now inclining to credit him with some originality and even linguistic creativity.210 He was not naively epitomising, however; in his preface, which took the form of an epistle, Justin suggested he was arranging an anthology of instructive passages, omitting ‘… what did not make pleasant reading or serve to provide a moral.’211 These selections were akin to the Greek classroom preparatory exercises, but now arranged as a history, and for all we know Justin might have simply been a student on such a syllabus. As Carol Thomas recently pointed out, Romans grew up with Alexander and: ‘As a schoolroom staple he was a key figure in hortatory texts.’212

The petals of Justin’s self-titled florum corpusculum, a little body of flowers, have sadly fallen too far from the original roots to tell us more about Trogus’ pages.213 Nonetheless, Justin’s brief resume of his history is, sadly, the only surviving continuous narrative of events in the Eastern Mediterranean that spans the whole of the Hellenistic Age. Less optimistic is Tarn’s conclusion of Justin’s efforts: ‘Is there any bread at all to this intolerable deal of sack?’214

OILS ON OIL AND PEARLS IN A PIG TROUGH

Tarn’s 1948 source study also assaulted Curtius’ Historiae Alexandri Magni Macedonis, if that indeed approximates the original title of our third extant book, and so enigmatic, though influential, is Curtius’ work, that we dedicate a later chapter to his identification.215