Elizabeth Jackson’s conviction for witchcraft was not the end of the story. As we shall soon see, a radically different interpretation of Mary Glover’s afflictions had been proffered at her trial. The judge rejected that testimony, as did the jury. But it was an alternative account that had a long pedigree, and its proponent was a respectable man with powerful political allies. Mary was not bewitched, but hysterical, or so it was alleged. Where had that term come from? What is that disorder, whose biography is our subject?

Hysteria is a pathological condition with a fascinating and tortuous medical and cultural history. If the malady seems to change its shape and its form over the centuries, who can be surprised? For here is a disorder that even those who insist on its reality concede is a chameleon-like disease that can mimic the symptoms of any other, and one that somehow seems to mold itself to the culture in which it appears.

The nineteenth-century American neurologist and novelist Silas Weir Mitchell invented what was once the most widely used treatment for this affliction, his famous rest cure, and grew rich on the proceeds from the hundreds of hysterics who annually crowded into his Philadelphia consulting rooms. Yet, like most of his medical colleagues, he pronounced himself baffled by much of what he saw: the trances, the fits, the paralyses, the choking, the tearing of hair, the remarkable emotional instability, all with no obvious organic substrate. Hysteria was “the nosological limbo of all un-named female maladies,” a condition that so challenged his powers of understanding and his therapeutic skills that he often referred to it in tones of exasperation as “mysteria.”1 Like the doctors who once despaired of its mysteries, perhaps the historian who ventures to write the biography of so elusive a subject will learn to rue the day he or she ventured upon such a Sisyphean task. Hence surely Edward Shorter’s lament: “Writing a history of something so amorphous, whose meaning and content keep changing, is like trying to write a history of dirt.”2 But it is also possible to revel in hysteria’s ambiguities and contradictions, as I prefer to do.

Was hysteria “real” or fictitious, somatic or psychopathological? Might it constitute an unspoken idiom of protest, a symbolic voice for the silenced sex, who were forbidden to verbalize their discontents, and so created a language of the body? Perhaps it was simply an elaborate ruse, a complex kind of malingering and manipulation that rendered its baffling, infuriating patients worthy of blame and punishment? Or, in the alternative, was it no more than a diagnostic waste bin, a heterogeneous congeries of complaints cobbled together linguistically, mostly a testimony to medical myth-making, incomprehension, and ignorance? At various times, and sometimes simultaneously, all of these claims have had their advocates. It is small wonder that the prominent mid-twentieth-century British psychiatrist Eliot Slater spoke contemptuously of the diagnosis as “a disguise for ignorance and a fertile source of clinical error … not only a delusion but also a snare.”3

How, in the face of such contradictions and uncertainties, are we to proceed? How can we define the very subject of our inquiry? It does no good to declare that one’s subject is “behavior that produces the appearance of disease.” Not only does that avoid one of the questions at issue, but it does so in a way that requires us to second-guess doctors and patients throughout most of human history. Certainly, by the twentieth century, most doctors had convinced themselves that hysteria was a psychological disorder, “an affliction of the mind that was expressed through a disturbance of the body.”4 But, for centuries before, physicians had insisted that hysteria was a “real” somatic disorder, and those suffering from hysterical afflictions have continued so to insist, for the most part, right up to the present. And sometimes the patients are proved right: in the heyday of psychoanalysis, all sorts of complaints that had been diagnosed as hysterical were subsequently proved to have a physiological cause, a category mistake that could have profound, even fatal, consequences for the individuals concerned.5

Moreover, the perils of retrospective diagnoses of what was “really” wrong with patients in the past are clear. Second guessing that is little more than speculation is never very helpful. So, by and large, mine is a biography of what contemporaries saw and interpreted as hysteria. I accept that, as with other diagnoses from the past, our still fallible contemporary versions of medical science might now assign them to very different categories of disease. Even choosing this option, though, does not provide a neat solution to the dilemma of what to include in the hysterical universe.

In a variety of historical settings, the decision about whether to apply the hysterical label was essentially a contested one, never finally resolved. In others, an alternative medical label was proffered, though whether the distinctions in question were real and substantial was acknowledged to be doubtful, even at the time. Thus, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, there was much anguishing about the distinctions between hysteria, hypochondria, the spleen, and the vapors, though for many informed physicians this was seen as so much hair-splitting, rather than corresponding to a clearly separable set of disorders. In the late nineteenth century, the construction of neurasthenia, or weakness of the nerves, was similarly controversial. Some alleged that it was a subterfuge to create a label more acceptable to men who shrank from being called hysterical (though, confusingly, there were a multitude of female neurasthenics). Others simply adopted the term as a convenient fiction, while cheerfully acknowledging that there was no clear dividing line between hysteria and neurasthenia. In the First World War, “shell shock” was originally thought to be a neurological disorder. Only later did most (but by no means all) informed medical opinion on both sides of the conflict come around to the view that it was an epidemic of male hysteria. And, in our own time, disputes rage about whether such entities as “chronic fatigue syndrome,” Gulf War syndrome, and myalgic encephalomyelitis are merely a modern manifestation of hysteria, or “genuine” illnesses. Such ambiguities and roiling disputes are part and parcel of the strange biography of hysteria, and, rather than ignore them, I have chosen to make them a central part of the narrative that follows.

The biography of such a disease, if disease it be, obviously cannot be reduced to a simple story. Not that others haven’t tried. For the Freudians, hysteria is the quintessential psychodynamic disorder, and its history a tale of fallacious medical materialism alternating with superstitious attributions of spirit possession and demonology, occasionally interrupted by brave pioneers who reject both forms of prejudice and perceive its true, psychological origins. Enlightenment finally triumphs with the advent of Sigmund Freud. For the famous critic of contemporary psychiatry Thomas Szasz, the very recognition of hysteria’s non-somatic origins is proof that it does not deserve the status of a disease, but is instead the locus classicus of the medical manufacture of madness, with doctor and patient down through history playing an elaborate, bad-faith game. Mental illness, Szasz proclaims, is a myth, and hysteria perhaps the most telling illustration of the mythological character of psychiatry’s proclamations. I shall advance no such simplicities here.

Many—indeed most—of the diseases we currently recognize have appeared since the beginning of the nineteenth century. That should occasion no surprise. For those committed to the notion of medicine as a developing science, it seems obvious that, as that science advances, its conceptions of etiology and pathology evolve, new discoveries force the reassessment of traditional categories, and an ever more complex account and classification of diseases result.

All save the most doctrinaire proponents of the idea that disease is socially constructed will concede that there is much to be said for this account. As our understanding of our bodies has grown, such broad categories as cardiac or pulmonary disease, or diseases of the nervous system, have inevitably been elaborated into more and more complex arrays of disorders, many of them named after those who “discovered” them (or occasionally, as with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig’s disease, named after those who were unfortunate enough to suffer from them). One may adopt a more sociologically sophisticated perspective on these developments, noting that disease categories may be politicized (as with the construction and deconstruction of homosexuality as a disease), and that decisions to construct diseases in particular ways are often debatable and negotiated. Rather than timeless entities that “cut nature at the joints,” disease entities are complex cultural productions. They depend upon layers of interpretation being placed upon whatever underlying physiological and psychological disturbances give rise to them. As such, they (and their boundaries) are inevitably subject to contestation and renegotiation, and not just because of the accumulation of new “knowledge.” The fundamental point remains: the realm of disease is unstable, with etiologies and nosologies always exhibiting some degree of flux, and doctors are generally no more able than their patients to shake themselves free of the assumptions and prejudices of their era.

And there is another reason why most diseases date from the past two centuries: till then, Western medicine shied away from the notion of disease specificity. Indeed, the promotion of such notions was often seen as one of the characteristics of quacks and charlatans. For millennia, disease was viewed in a holistic way, as the product of systematic disturbances in the balance of forces that characterized each of us. Diagnosis and treatment were a matter of working out where the balance of humors had gone astray, and deciding how to bring them back into equilibrium.

Doctors from the early nineteenth century onward were eager to tie their nosologies and diagnoses to observations at the bedside or, still more persuasively, findings in the laboratory. In earlier centuries, however, appeals to the canonical texts of Hippocrates and Galen were standard ways of legitimizing diseases and their treatments. In linking particular diseases to these authorities, medical men in early modern Europe (and the patients who embraced their nostrums) were connecting their ideas and practices to a tenacious, broadly shared, and authoritative universe of meanings, beliefs, and behaviors. And certain features of their medical cosmology made the promulgation of the disease of hysteria plausible to themselves and those they treated. Their notions of health and disease set up no firm division between body and environment, the local and the systemic, soma and psyche, each element in these dyads being capable of influencing the other. The part and the whole were inseparable and inextricably tied together, with disequilibrium in any corner or cranny threatening the equilibrium (and thus the health) of anybody or any body.

Here was a set of culturally shared understandings of the sources of disease and of its therapeutics that persisted with very little change for centuries. The body was held to be a system in constant dynamic interaction with its environment, so tightly interconnected that local lesions produced systemic effects. Seasonal changes as well as developmental crises over the course of a lifetime constantly threatened the equilibrium of the system, and thus the health of the patient. Bodies assimilated and excreted, and were affected by diet, exercise, and regimen, as well as pre-existing constitutional endowment, all of which might change the balance of the humors and thus the health, physical and mental, of the patient. Upset bodies produced upset minds, and vice versa. It was the job of the physician to recognize why the equilibrium that was good health had been thrown out of kilter, and then to mobilize the tools at his disposal to affect a readjustment of the patient’s internal state. Ritually reaffirmed through the therapeutic encounter, “the system provided a rationalistic framework in which the physician could at once reassure the patient and legitimate his own ministrations.”6

Women were different. Of that there could be no doubt. And the differences were consequential for their health. Hence the disposition of physicians in the ancient world to place women’s reproductive systems at the heart of accounting for their susceptibility to all sorts of disease and debility. In women, so one Hippocratic text read, “the womb is the origin of all diseases.” It was not just that the female of the species was differently constituted from the male; she was also fundamentally inferior: moister, looser textured, softer, with spongier flesh. Her body was more readily deranged—for example, by puberty, pregnancy, or parturition, by menopause, or by suppressed menstruation, all of which could impose profound shocks on her internal equilibrium (for her wetter constitution produced an excess of blood, which regularly needed to be drained from her system); or by the womb wandering about internally in search of moisture (or, later, sending forth vapors that rose through the body), disturbances that were held to be the source of a great variety of organic complaints. It was from these notions, reworked by Galen and other Roman commentators, and for the most part re-entering the West from Arabic medicine in the Renaissance, that the classical accounts of hysteria were constructed.

Plato’s Timaeus, in George Rousseau’s vivid précis, had viewed “the womb as an animal: voracious, predatory, appetitive, unstable, forever reducing the female into a frail and unstable creature.”7 Many medical writers of the Classical Age were not inclined to disagree. Certainly, as Helen King has done much to establish, the presence of a full-blown clinical description of hysteria in the Hippocratic texts is a modern fable, but the notions of a wandering womb, and of women’s gynecology as the source of a multitude of mental and physical ills, can certainly be found there. And they were amplified and debated in the Roman era.

Celsus and Aretaeus, closely associated with the Hippocratic tradition, both adopted the notion of the womb wandering about the abdomen, stirring up all manner of troubles. If it migrated upward, for example, it compressed other bodily organs, producing a sense of choking, even a loss of speech. “Sometimes,” Celsus claimed, “this affection deprives the patient of all sensibility, in the same manner as if she had fallen in epilepsia. Yet with this difference, that neither the eyes are turned, nor does foam flow from the mouth, nor are there any convulsions: there is only a profound sleep.”8 Both Soranus and Galen, by contrast, disputed the notion that the womb could wander, though they accepted that it was the organ from which hysterical symptoms derived. These manifestations of the disease could take a multitude of forms: extreme emotionality; but also a variety of physical disturbances, ranging from simple dizziness, through paralyses, and respiratory distress. Then there was the commonly reported sensation of a ball in the throat, constricting breathing and creating a sense of suffocation, the so-called globus hystericus.

There was thus a venerable tradition within Western medicine that linked hysteria to gender—and perhaps even to sexuality, for Galen held that sexual deprivation could cause the disorder, and advocated intercourse for the married, and marriage for the single, as a frequently valuable therapeutic tactic. It was a tradition that firmly located an array of strange bodily symptoms that others might be tempted to attribute to the supernatural—to bewitchment, or to possession by devils—to the material universe, and to disorders of the female body. And it was a tradition that was invoked for the first time in an English courtroom at the dawn of the Jacobean age.

The trial of Elizabeth Jackson had led, as we saw in the Prologue, to her conviction for bewitching young Mary Glover, a conviction that for many contemporaries was amply warranted by the facts. But she had had a defender who was not from her neighborhood, nor one of the audience who considered young Mary a counterfeit and a fraud, nor one of her class or background at all. Instead, one of England’s medical elite had taken the witness stand, and he had tried to invoke what authority his profession possessed to rebut claims of witchcraft and to provide what he claimed was an explanation sanctioned by Galen and Hippocrates.

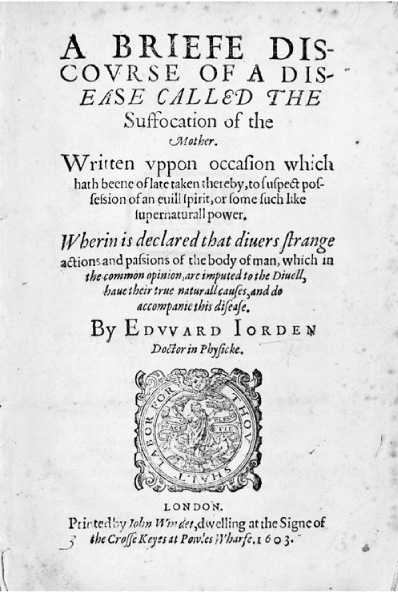

Curiously, as it may seem at first, Edward Jorden, an influential member of London’s College of Physicians, had chosen to appear on poor widow Jackson’s behalf. The burden of Jorden’s testimony, and of a subsequent pamphlet he published on the case, was that Mary Glover suffered from “hysterica passio” or “suffocation of the mother.”9 Hers was an instance not of demonic possession, but of a bodily illness. It belonged, in other words, to the world of the natural, not the supernatural. Accordingly, Elizabeth Jackson was wholly innocent of the charge of witchcraft.

1. The Suffocation of the Mother. Title page of Edward Jorden’s pamphlet. (Wellcome Library, London)

In support of his claims, Jorden was quick to point to women’s greater susceptibility to disease, and to their particular susceptibility to the “suffocation of the mother,” because of the womb’s close connections with “the braine, heart, and liver … and the easie passage which it hath into them by the Vaines, Arteries, and Nerves.”10 Here was a disease whose symptoms were “monstrous and terrible to beholde, and of such a varietie as they can hardly be comprehended within any method or boundes”—and liable to deceive the credulous and the unlearned, who all-too-readily ascribe them “either to diabolicall possession, to witchcraft, or to the immediate finger of the Almightie.”11 One particularly common affliction was a sense of “suffocation in the throate.”12 Hence the disease’s common vernacular name.

But, in arguing for the protean quality of hysterical complaints, Jorden was opening himself up to ridicule and rebuttal. In the course of his testimony he was asked whether he could cure Glover, and he confessed he could not. Would he treat her? No, he would not. Was Glover counterfeiting and a fraud? No, she was not. (It would have been difficult for Jorden to assent to this last query, for not long before, in front of the judges, Mary had once more been accused of faking her symptoms, and had had her hand severely burned, an ordeal she bore without blinking or evident sign of distress.)

Disdainfully, Sir Edmund Anderson dismissed Jorden’s testimony: “Then in my conscience, it is not naturall; for if you tell me neither a Naturall cause of it, nor a naturall remedy, I will tell you, that it is not naturall … I care not for your Judgement.”13 Instructing the jury, he pointed out that widow Jackson had stumbled once more over the words of the Lord’s Prayer and the Creed, and bore on her body the witch’s mark. “Phisitions [Physicians],” however “learned and wise,” had confessed their ignorance of both cause and cure: “geve me a naturall reason, and a naturall remedy, or a rush for your phisicke.”14

The jury, who doubtless shared Anderson’s view of the world, had no hesitation in convicting, and the judge had no hesitation in sentencing Jackson to prison and the pillory. But it was a sentence Jackson would never serve, for her influential supporters quickly secured her release. In a way, one might say that she was doubly fortunate, for she had been convicted under the relatively lenient terms of the Witchcraft Act of 1563. Two years after her trial, the law was revised, and even witchcraft that did not result in the victim’s death became a capital offense.

Spurned in the courtroom, Edward Jorden was not yet done with the case. Within months, he had produced and published a lengthy pamphlet spelling out for his readers the etiology and symptoms of “a disease called the Suffocation of the Mother,” afflictions that “in the common opinion, are imputed to the Devill.”15 Where before he had vacillated on the question of whether Mary Glover had been a fraud, he now emphatically denied it. It was an affliction of her uterus and subsequently of her brain that had brought on her symptoms, and it was thus to medicine, not the interventions of divines, that one should look for a cure.

For if it be true that one man cannot be perfect in every arte and profession … Why should we not prefer the judgements of Phisitions in a question concerning the actions and passions of mans [sic] body (the proper subject of that profession) before our owne conceites; as we do the opinions of Divines, Lawyers, Artificers, &c. in their proper Elements.16

Foul and fragrant smells, tight lacing, and a sparing diet could and should be employed to calm and remove the fits.

It was an opinion largely ignored or rejected in its day. Mary Glover had continued to have fits, even after Jackson’s conviction, till her parents, pious and prominent Puritans, summoned divines and the devout to her bedside to pray and to fast, and so to cast out “her devills.” A day of struggle supervened. As the assembled believers prayed over the young girl, her body acted out her inner turmoil. She was wracked by convulsions and contortions, which grew in intensity till the climatic moment arrived, and the devil seemed to leave her, as she cried out that God had come and that the Lord had delivered her. For her Puritan audience, the proof of her possession could not have been clearer, for those were the very words her grandfather had uttered as he burned to death at the stake, the victim of the “Papists” unleashed during the Catholic reign of terror that accompanied Queen Mary’s brief tenure on the English throne. Their religion, their God, had been vindicated by Mary Glover’s case, and Satan cast out of her body.

As the historian Michael MacDonald has shown, it was this very ritual of dispossession that had prompted the appearance of Edward Jorden’s pamphlet. As Jorden himself confessed in its opening lines, “I have not undertaken this businesse of mine own accord.”17 Instead, he had been commissioned to write it by the Bishop of London, Richard Bancroft. To modern eyes, the text looks like an effort to forward the claims of a secular naturalism ranged against the traditional claims of religion. In reality, however, MacDonald argues that it was first and foremost itself a piece of religious propaganda, forming part of the two-front war orthodox Anglicans were engaged in: on the one hand, against the Jesuits and other agents of idolatrous Popery; and, on the other, against the claims of a clamorous band of Puritans bent on recruiting the English state to their cause. The stakes were all the higher, because the death of Queen Elizabeth had brought to the throne James, the King of Scotland, a man who had previously demonstrated his own enthusiasm for Daemonologie in his 1597 pamphlet with that title.

Both Catholics and Puritans used what they saw as miracles to advance the legitimacy and authority of their faith: Jesuits could rely upon an elaborate ritual of exorcism to eliminate supernatural afflictions, and had performed some spectacular and well-publicized rites, the driving-out of demons proving potent propaganda for their cause. Their Puritan opponents, dismissing the Papist ceremonies as superstitious nonsense bereft of biblical authority, nonetheless invoked a passage in the Gospel of Mark, where Jesus supposedly attributed His cure of a youth afflicted with a “deaf and dumb spirit” to the power of prayer and fasting, to justify developing their own weapon against Satan’s wiles. Fearful of both religious extremes, the English state had tried straightforward repression of both groups, banning books, and imprisoning practitioners. Jorden’s text represented a different tack in the same struggle, an intellectual counter-blast designed to discredit both forms of exorcism, and thereby to weaken the appeal of those practicing them.

Bancroft, and his aged superior, John Whitgift, whom he would succeed as Archbishop of Canterbury, were rightly notorious for their rigid intolerance of Puritans. Fortunately for them, they seem to have succeeded in persuading King James to share their hatred for “insolent Puritanes” as well as “superstitious Priests,” the twinned enemies of true religion who were the targets of his wrath in his 1604 Counterblast to Tobacco. Bancroft introduced Jorden to the King, and not long after, and perhaps not coincidentally, James abandoned his earlier enthusiasm for witch-hunting, preferring instead to make sport of exposing frauds and imposters pretending to be possessed.

In that sense, Jorden’s arguments won the day, at least at the level of high politics, and one might even argue that they indirectly played a role in the diminution and eventual disappearance of the legal persecution of “witches.” Elsewhere, however, it was a different story. Repressed they might be, but Puritans and their sympathizers continued throughout the seventeenth century to circulate the story of little Mary Glover, her possession and dispossession. It was a triumph for, and a testimony to, the truth of their religious convictions. And, among his fellow physicians, Jorden’s pamphlet was little noticed, and soon forgotten. Even when he wrote it, many of his colleagues in the College of Physicians had signaled their belief that Mary Glover was indeed bewitched. A Briefe Discourse of a Disease Called the Suffocation of the Mother had but a short half-life and then disappeared from view, never reprinted, seldom cited, left to the gnawing criticism of the mice. With it went any serious interest in the disease it claimed to identify, and that interest would not revive for several decades.

And yet, Mary Glover’s case displays some remarkable features, phenomena that we shall encounter again and again as we trace the curious career of the now-vanished disease known as hysteria. Take her symptoms, for example. Loss of speech and sight, and an inability to swallow; paralyses of hands, arms, legs; mysterious swellings of the abdomen or throat; a sense of suffocation; odd breathing patterns; loss of sensation and of reflex action—all these are classic recurrent features of something, a putative syndrome that in later centuries came to be seen as the manifestation of hysteria. Then there are the assumptions of odd postures and facial expressions, the writhings and contortions, and the strange vocal tics. These, too, we shall encounter in some very different settings. As for the preternatural ability to transform one’s body into a circle and roll around the room like a human wheel, performances of this sort, labeled the arc-en-cercle, would become one of the features of the hysterical circus to which the eminent neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot would serve as ring-master in late-nineteenth-century Paris. Above all, of course, there is the dramatic character of all these symptoms, the striking impression they made on any and all who had occasion to witness them, arousing the persistent suspicion that what was being watched was in reality an act.

That many medical men should profess themselves baffled by these strange manifestations, and that some would deny that what they were observing was a natural disease, is again a feature we shall observe repeating itself. Many suspected that Mary Glover was faking her symptoms. Even Edward Jorden at times seems to have joined the ranks of the skeptics. Many of Mary’s symptoms aroused suspicion, and seemed conveniently calculated to take revenge on the old woman who had abused and frightened her. If Elizabeth Jackson wanted her dead, she would respond in kind: “Hang her, hang her.” Perhaps it was all an elaborate act, a malingering, a calculated use of bodily symptoms to gain social advantage. These, too, would be familiar features of the disorder, as would the failure of threats and even the infliction of severe pain to have a discernible effect on the sufferer.

And yet, if it was all an act, how was Mary Glover able to endure the burning of her flesh, or the approach of a flame that seemed destined to blind her? The mass psychiatric casualties of a war centuries in the future would exhibit convenient symptomatology that would arouse great suspicion, even disbelief, among those around them. Surely they were malingering, or making things up; they were really cowards who had lost the will to fight, and who sought to use mutism, tremors, sudden claims of blindness, or paralysis as excuses to avoid doing their duty. Yet these men, too, when subjected to creative, painful and sadistic treatments designed to flush out their fakery, would endure and persistently present their dubious deficits.

Still, hysterical men would be the exception, not nearly as rare as is often believed, to be sure, and certainly existing in defiance of one very common view of the disorder, that it was rooted in the female reproductive organs, more specifically, the womb (whether wandering or otherwise)—as its very name, deriving from the Greek word for that organ, hystera, would imply. More commonly, though, the hysterical patient would turn out to be female, and such remain the common-sense associations the word “hysteria” conjures up, in an age when professional psychiatrists have essentially abandoned the diagnosis. So here, too, Mary Glover is in some ways the prototypical hysterical patient, young and, more especially, female (though possibly a little too young for many, since she menstruated for the first time some months after the whole episode began). Gender plays a large and complex role in the biography of hysteria, so it is perhaps fitting that the first prominent English patient to be considered a hysteric should be a young unmarried girl.

And what of religion, that competing explanation of the London teenager’s fits? That too will resurface as part of the biography of this baffling, recalcitrant, protean disorder, though, like Marx’s Hegel, it will, in the process, be turned upside down. If the divine and the diabolical had once been invoked to account for hysterical symptoms and their cure, in centuries to come, in a secular not spirit-drenched world, hysteria would be a label put forth to explain away and discredit extreme varieties of the religious experience—the trances, the fugue states, the physical endurance, and the willingness to suffer of those Christians whom earlier generations of their co-religionists preferred to regard as saints.