War, as the bumper sticker would have it, is not good for children and other living things. For medics, though, it is another matter entirely. The wounds of warfare, it goes without saying, require much medical attention—to keep up the morale of the troops, if not actually to cure many of those treated. (Prior to the spread of aseptic surgery, battlefield mortality was frightful, and medicine’s weapons against infectious diseases, which regularly decimated the troops, were equally weak and unsatisfactory.) But beyond that, war allows army medics to observe the impact of all sorts of trauma on the human body, an array of naturalistic experiments from which much can potentially be learned, and which could never be replicated on a similar scale in normal times, even among such vulnerable populations as the mentally ill and the mentally retarded.

The American Civil War, one of the first modern, mechanized wars, and one that went on for years, producing massive quantities of dead and wounded, provides a classic illustration of this thesis. Prominent figures in military medicine seized on their experiences to learn new lessons about the pathology of living bodies, lessons they subsequently drew upon and exploited in the years following the war. The Philadelphia society doctor Silas Weir Mitchell, and his colleagues W.W. Keen and George Morehouse, produced a monograph on Gunshot Wounds and Other Injuries of Nerves, and, in the aftermath of the war, Mitchell set up shop as part of a new breed of medical specialists, neurologists, a branch of the healing arts in which he was soon joined by, among others, the man who had served as Surgeon General of the Union Army, William Alexander Hammond.

American neurology, as a clinical specialty, can thus trace its origins to the impact of war. That was true in another sense, of course, for many of the patients who thronged the waiting rooms of these new “nerve specialists” were soldiers who were casualties of the fighting. Some had obvious traumatic injuries to their heads, their spinal cords, or their peripheral nervous system. Others had wounds that were more difficult to trace, perhaps, as few dared to hint, even imaginary or the product of the psychological trauma they had experienced. But there was still another group of patients who began to show up in increasing numbers, and here there could be no question of battlefield trauma, physical or psychological—for these were members of the fairer sex, hysterics who descended on the new group of specialists as though they represented manna from Heaven. General practitioners had failed them. Gynecologists had not yet come up with a distinctive new therapy for their nervous clientele, though they would soon claim to have done so. If the neurologists were the new cutting edge of scientific medicine, if they knew more than anyone else about the disorders of the brain and the nerves, why then, who better to treat hysteria?

Willing or not, neurologists thus found themselves drawn into the maelstrom of functional nervous disorders, whether among army veterans or among wealthy society matrons (and their adolescent daughters), all importuning a diagnosis for their disorder, and the most modern, up-to-date, scientific treatment. Perforce they had to respond, and, in any event, the nascent state of their specialism, with its associated economic vulnerabilities, meant that they could scarcely afford to turn away such lucrative and persistent patients.

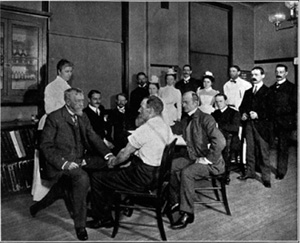

7. Silas Weir Mitchell (1829–1914), Philadelphia neurologist and novelist, the inventor of the “rest cure,” who grew rich from the hysterics and neurasthenics who flocked to consult him. He is shown here examining a Civil War veteran at the Clinic of the Orthopedic Hospital of Philadelphia. (Wellcome Library, London)

On yet another front, neurologists’ focus on disorders of the brain and the nervous system at least implicitly extended to a claim to expertise with respect to all forms of nervous and mental disease. In general, the problem of drawing clear distinctions between neurological and psychiatric disease was something Victorians wrestled with, but without making much progress. So, at least in theory, neurology was a rival to the asylum doctors, with their captive population of the insane. And, in practice, there can be little doubt that there was a fair degree of overlap between the patients who fetched up in neurological waiting rooms, and those who found themselves confined involuntarily in asylums. Certainly, the neurologists increasingly thought of themselves as embracing this whole spectrum of diseases, and conceived of themselves as infinitely better trained and more scientific than their professional counterparts—men they saw as detached from “scientific medicine,” having chosen to lock themselves into the asylums they presided over almost as securely as the patients they confined. They were, sneered the New York neurologist Edward Spitzka, experts in heating systems, running asylum farms, and disposing of sewage, “experts at everything except the diagnosis, pathology, and treatment of insanity.”1 As neurologists gave voice to their perceived superior knowledge and skills in this fashion, they inevitably provoked growing antagonism with the alienists, the branch of the mad-doctoring trade that practiced in asylums.

By the 1870s, the two groups of specialists were openly sniping at one another, and the feud grew nastier yet in the following decade. Simultaneously, however, both found themselves fending off yet another group of medical men who trespassed onto this territory. For the ignominious end of Isaac Baker Brown had not driven all the hysterical patients from the gynecologists’ waiting rooms, nor extinguished the interest of many of that specialty’s membership in ministering to so numerous and lucrative a clientele. The claimed connection between womb, ovaries, and brain now prompted the invention of another surgical remedy for hysteria.

The new operation, “normal ovariotomy,” was designed to produce an artificial menopause. Its originator, an American surgeon from Rome, Georgia, with the rather apt name of Battey, announced his breakthrough in 1873 in suitably apocalyptic tones: “I have felt it to be my duty to … carve [sic] out for myself a new pathway through consecrated ground … I have invaded the hidden recesses of the female organism and snatched from its appointed set a glandular body, whose mysterious and wonderful functions are of the highest interest to the human race.”2 Others, of course, had previously “snatched” ovaries from their appointed seat. Battey’s originality consisted in deliberately extending the operation to the extirpation of healthy organs. Hence the term “normal” ovariotomy, a choice of language he later came to regret.

Although Battey offered his operation as an effective treatment for a variety of pathological conditions that were held to depend upon the periodicities that plagued menstruating women, its allegedly marvelous curative properties were soon concentrated upon the treatment and cure of nervous ailments. As an operation on the external genitalia, Baker Brown’s clitoridectomy could be undertaken even in the pre-antisepsis era, with only occasionally fatal complications from fulminating infections. But ovariotomy—or, as it was also called, oophorectomy—became technically feasible on a major scale only once the importance of antisepsis had been grasped and generally accepted. Even then, during the first decade of the operation, mortality rates averaged one-third of all cases treated, so that those experimenting with the treatment found themselves generally condemned, and at times even ostracized.

By the 1880s, however, death rates had declined quite markedly, to what were regarded as more acceptable levels (Battey himself, for example, reported a series of 70 cases in 1886 with only 2 deaths and 68 “recoveries”), and, with the technical feasibility of the operation now established, a veritable mania for ovariotomy swept the United States and (to a lesser extent) Britain. The precise number of operations performed during the 1880s and 1890s can never be established, since they were, with a few exceptions, confined to private practice, or to general hospitals; but the English surgeon Lawson Tait himself performed several hundred, and, judging from the published cases alone, several thousand and quite possibly tens of thousands of women must have submitted themselves to the surgeon’s knife.

Almost all of them were those who hovered on the borderlands of insanity, the inhabitants of what the British doctor Mortimer Granville referred to as “Mazeland, Dazeland, and Driftland.”3 For the most part, asylum superintendents simply blocked access to institutionalized patients, reluctant to allow competitors into an arena they sought to monopolize, and fearful of the backlash from the public at large were they to allow hazardous experimentation on their captive population. It was thus hysterics and those who, in the words of the eminent Philadelphia gynecologist William Goodell, “hovered on the narrow borderland that separates hysteria from insanity,”4 who were the usual beneficiaries of Battey’s operation, typically middle- and upper-class women. Doctor, patient, and family could agree, with few qualms, that, as a way station on the road to chronic insanity, hysteria called for drastic measures designed to secure what Goodell termed “a ray of hope,” perhaps the “only chance,” of staving off a life of permanent invalidism or, worse still, the stigma of confinement in an asylum.5

Once the operation became widely known, doctors reported that they were besieged by women begging for the treatment. Some of these statements may have been self-serving, a means of heading off criticism from the rest of the medical profession or from the public at large about the wisdom of persuading women to submit to such an irreversible operation, one that blighted forever the prospect that their patients could contribute to that most vital and sacred of feminine tasks, the propagation of the species. But it would be wrong to be too cynical. The reports came from so many quarters, from male and female physicians alike, that it is difficult to believe that they were simply invented. Besides, the spectacle of hysterics rushing to embrace a somatic account of their troubles is scarcely unknown in other times, even in our own. In this instance, the assault on the ovaries was in line with long-standing folk beliefs about the origins of women’s emotional lability, beliefs that had acquired a new veneer of scientificity with the development of reflex theories of nervous action. And ovariotomies at the very least served to end the endless cycle of pregnancies and parturition that was the lot of many Victorian women, a secondary gain some of the patients may deliberately have sought.

Neurologists, who had long been harshly critical of asylum superintendents for being out of touch with the cutting edge of medical advances, were even more contemptuous of the claims of the advocates of sexual surgery. Wharton Sinkler, an eminent Philadelphia neurologist, commented sardonically:

A first successful abdominal section seems to have the same effect upon an operator as the taste of blood upon the Indian tiger. A thirst insatiable is aroused, and life is spent in looking for new victims. Cases running into double and triple figures are cited, where all the worst features of the most stubborn nature have disappeared, as though the surgeon’s knife were gifted with the power of an enchanter’s wand.6

Reasserting that insanity and related conditions were the product of “nerve exhaustion” or disease, and hence belonged securely within the neurologist’s province, other neurologists accused their colleagues of having fallen into a trap: “We are liable to be misled by what we see,” particularly in cases of hysteria, “which very much simulate organic disease.”7 But such cases merely counterfeited organic mischief, while the true causes of the disorder resided in the nervous system.

Consistent with these judgments, leading neurologists routinely denounced ovariotomy as a treatment for hysteria as simply a mutilation, a variety of “heroic surgery, of … the most flagrant and pernicious form,” whose “evil and uselessness can not be too strongly condemned.”8 Others were a little more restrained, though scarcely less critical. The New York neurologist Archibald Church argued that, even were one to assume that the procedure had some therapeutic value, it was far too drastic and dangerous to be employed against “a comparatively hopeful malady [like hysteria]”; while his Boston colleague Robert Edes cautioned that, despite all the exaggerated claims, “the relief is either none at all or only such as may be temporarily obtained from any strong impression whose effect is hopefully awaited.”9

By the mid-1890s, these doubts had spread among elite gynecologists, and, as a treatment for hysteria, ovariotomies rapidly declined in popularity. Accumulating experience was discrediting the earlier optimistic claims about the operation’s therapeutic impact, and increased knowledge about the importance of “glandular secretions” to women’s health cast doubt on the wisdom of extirpating the ovaries. At least as important were growing ethical qualms that arose, ironically, from these male doctors’ beliefs about woman’s place in society. The claim to be proceeding in the hysterical woman’s best interests “was hard to square with the general belief that ‘ovariotomy’ ruins a woman in all the essentials of womanhood.” For moral reasons, “a mutilated woman” could not hope to marry. Who would have her? Without the possibility of procreation, a woman who engaged in sexual relations was little better than a whore. The gynecologist who brought about this parade of horribles could thus count himself, in the words of Howard Kelly of Johns Hopkins, the leading gynecologist of his age, “the destroyer of everything that makes a woman’s life worth living.”10

While gynecologists continued to see and treat the hysterical, their new claims to possess a distinctive treatment for the disease were severely damaged by this episode. Neurologists, by contrast, confidently proclaimed that their specialty was developing an ever more elaborate understanding of the nervous system and its disorders, and that they had an impressive array of treatments for these conditions, all capable of stimulating and restoring nervous action. The nervous system was increasingly seen as mediated through electrical signals, and for a decade or two electrotherapy in its various forms became a distinctive feature of neurological practice. Shiny and impressive chrome and brass machines delivered jolts of static electricity, and faradic currents were likewise employed to shake up the system, rearranging, as the neurologists solemnly assured their patients, the molecular structure of their bodies and simultaneously affecting the reflex actions of the nervous system. Drugs, too—ergot, strychnine, chloral, the bromides, arsenic, caffeine, Indian hemp, the opiates, and various proprietary tonics—were touted for their alternative value in stimulating and calming the nerves. And diet and regimen were mobilized in the cause. American neurologists bemoaned the trials of dealing with the hysterical and the nervous. Silas Weir Mitchell spoke of hysterics as a “hated charge” of his specialty, and lamented that “hysteria” might better be termed “mysteria.”11 But he agreed with his New York colleague George Beard that “nervousness is a physical not a mental state, and its phenomena do not come from emotional excess or excitability or from organic disease but from nervous debility and irritability.”12

General practitioners, like much of the public at large, were in many cases not convinced. To be sure, hysterics and nervous invalids exhibited many signs of suffering. Their complaints were loud and long, and their apparent physical symptoms—nervous prostration, fits, headaches, paralyses, floods of tears, and exhibitions of emotional lability, insomnia, and invalidism—were dramatic and disturbing. But were they real or imaginary? To be sure, they were tenaciously held on to, often at considerable cost. But these querulous creatures visibly enjoyed all sorts of secondary gains alongside these primary losses. Complaints that hysterical women were deceitful, manipulative, selfish creatures permeated many medical discussions of the problem they represented, one reason the British physician F. C. Skey recommended that they be treated with “fear and the threat of personal chastisement.”13 Their tricks and tantrums were, in the words of the leading English alienist of the period Henry Maudsley, a form of “moral perversion,” and their resort to the sick bed a sham, “when all the while their only paralysis is a paralysis of the will.”14 Were these hysterical women in reality cynical malingerers, whose troubles were all “in their minds”?

It was a charge Weir Mitchell and his neurological colleagues fiercely resisted, and the more they insisted, drawing upon their prestige as those with the most expertise in the study of the nerves, that hysteria and allied complaints were genuine disorders of the body, the more the neurotic flocked to their consulting rooms. By way of consolation, hysteria was undoubtedly more treatable than the scleroses, the paralyses, the tics and epileptic fits, and the depressing array of tertiary syphilitics that were otherwise the neurologists’ lot. And the legitimacy the “nerve doctors” conferred on the disorder ensured an ever large pool of patients, most from highly affluent and thus ultra-desirable circles. Mitchell’s patients, for example, besides an array of society’s grandes dames, included such prominent figures as Jane Addams, Winifred Howells, Edith Wharton, and Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and his ministrations to their needs made him an extremely wealthy man. Gilman skewered him and his rest cure in her novella, The Yellow Wallpaper, written in 1890 and published two years later. As she wrote in her journal, the enforced inactivity and complete absence of mental stimulation that Weir Mitchell enforced brought her “so near the borderline of mental ruin that I could see over.” (Gilman sent her “fiction” to her doctor, who never acknowledged receiving it.)

By no means all the “nervous” patients who fetched up in the American neurologists’ consulting rooms were women. For a brief period, the nervous man posed something of a challenge, for the nerve doctors were reluctant to extend the label of hysteria to encompass the male of the species, and the eighteenth-century male analogue, hypochondria, had by now acquired much of its modern meaning, an obsession with imaginary ills. Mitchell’s New York colleague George Beard soon provided an intellectual solution to the difficulty. Nervous men, he announced, were suffering from neurasthenia—literally, weakness of the nerves—a condition brought on by overwork and overstress.

8. Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860–1935), one of Silas Weir Mitchell’s best-known patients. (Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University)

A century and a half earlier, George Cheyne had spoken of “the English malady,” and had made what foreigners had considered a reproach—the heightened susceptibility of the English to hysterical disorders—a marker of England’s prosperity, success, civilization, and refinement. Beard now spoke of “American nervousness” in analogous terms, as a maker of national superiority. American women, he noted complacently, were far and away the most beautiful in the world, their faces exhibiting an unparalleled combination of “delicacy, fineness, and mobility of expression.”15 Where “the English face is molded, the American is chiseled … the superior fineness and delicacy of organization of the American woman … revealing itself in the play of the eyes, the voice, in the response of the facial muscles, in gait, and dress, and gesture,” but also in heightened susceptibility to nervous prostration.16 Among Americans, male and female alike, it was the country’s economic and cultural superiority that provoked so many nervous crises. The constant striving for success; the speed of modern life as exemplified by the telegraph and the steam engine; the excitement induced by the periodical press; the hurry of social change as unfettered capitalism allied to the powers of science revolutionized production and all aspects of daily life; and the increased mental activity of women: these were unique features of nineteenth-century civilization, but features that were felt with their full force only in America. “American nervousness, like American invention or agriculture, is at once peculiar and pre-eminent.”17 Striving and succeeding, the entrepreneurial American was always at fever pitch. But human beings possessed a finite store of nervous energy. Those who overtaxed their systems ran down their batteries, overloaded their circuits, overdrew their accounts, bankrupted their nervous systems, and were prone to breakdown.

The source of these analogies is plain, as is their appeal. Neurasthenia was a disease of the distinguished, of the best and the brightest, of the wealthy and the cultured, for it was these segments of society who were most exposed to the stresses and pressures of modernity, whose nervous systems were stretched tightest, eventually to breaking point. Bankers, lawyers, doctors, titans of industry and commerce, those who worked with their brains, not their hands (“the civilized, refined, and educated,” in Beard’s apt summary, “not the barbarous and low-born and untrained”18)—these were the gentlemen at greatest risk, and their nervous prostration was thus a sign of their superior endowments and attainments—a diagnosis and an etiology that flattered the neurasthenic while reassuring them that theirs was emphatically a real physical illness, not some sign of weak will or self-indulgence. He counted himself among its victims, and a distinguished list it was: William and Henry James, Louis Agassiz, Theodore Dreiser, and W. E. B. Du Bois among Americans; John Ruskin, Francis Galton, Joseph Lister, Arnold Toynbee, and John Bright in England, to cite only a handful of eminent men who suffered from grave “nervous prostration.”

The symptoms of neurasthenia or nervous collapse were many and varied and little different, if at all, from the protean symptoms that marked its twin, hysteria: sleeplessness, indigestion, weakness of the eyes, uterine irritation, chronic indecisiveness, permanent anxiety, irrational fears, impotence, heaviness of loin and limb, headache, neuralgia, flushing and fidgetiness, spasms and paralyses, claustrophobia and fears of contamination, to name but a few. Their protean character was a reflection of the overuse or abuse of the brain, the stomach, and the reproductive system. The consequence was an irritation or exhaustion of the nerve force, which, via reflex action, produced neurasthenia’s many and varied physical manifestations, a puzzling array of troubles that had yielded their secret underlying unity only to the neurologist’s probing gaze.

It would be too simple to dub neurasthenia the male version of hysteria, not least because many women soon populated the ranks of the neurasthenic, just as not inconsiderable numbers of men continued to be diagnosed as cases of hysteria. If it is clear that there was some gender preference in the allocation of diagnostic categories, it is equally plain that no clear dividing lines could be drawn between the two. Hysteria and neurasthenia were both perceived as protean nervous complaints, and it was simply not possible then (just as it is impossible today) to draw any hard and fast boundary between the two. Both male and female “nervous invalids” flocked to the nerve doctors’ waiting rooms, and patronized the growing number of hydropathic establishments and sanatoriums that emerged to provide extended periods of respite for the affluent and the idle who had succumbed to the pressures of civilized existence. Though the female hysteric occupied a more prominent place in literary and popular culture, “it is utterly erroneous,” as Janet Oppenheim rightly reminds us, “to assume that Victorian doctors perceived the male half of the human race as paragons of health and vigor, while assigning all forms of weakness to women. They could not have done so, even had they wanted to, for the evidence exposing male nervous vulnerability was too familiar to the Victorian public for pretense.”19

If hysteria and neurasthenia had the origins in a malnourished and overburdened nervous system, one that was often made manifest to the trained clinical eye in the form of a thin, tense, scrawny physique, the obvious solution was to build up the body in hopes of restoring the nerves. Hence the resort to tonics, and to efforts to build up the system. The basic problem was signified by the title of one of Weir Mitchell’s bestselling guides to laymen about nervous disorders: Wear and Tear, or Hints for the Overworked. And their therapeutics was neatly encapsulated in another of his medical advice books, Fat and Blood: An Essay on the Treatment of Certain Forms of Neurasthenia and Hysteria. Both passed through multiple editions, disseminating the neurologists’ message to a wide and eager audience.

Americans, Mitchell warned, were at risk of “overtaxing and misusing the organs of thought,” a problem compounded by the sedentary existence that brain work implied. When the illused brain at length rebelled, hysteria and neurasthenia were the inevitable result. Young girls were particularly at risk, for mental resources that ought to be conserved and directed towards their vital role as future wives and mothers were being frittered away in misguided mental pursuits and excitements. The facts of physiology implied that “it were better not to educate girls at all between the ages of fourteen to eighteen, unless it can be done with careful reference to their bodily health.”20 Externally, the outcome of neglecting this scientific imperative was an unfortunate “hardness of line in form and feature”21 mistakenly viewed as beautiful. More ominously, though, for the future of the American race, the outcome was nervous creatures whose “destiny is the shawl and the sofa, neuralgia, weak backs, and the varied forms of hysteria—that domestic demon which has produced untold discomfort in many a household.” “Only the doctor knows,” Mitchell continued, “what one of these self-made invalids can do to make a household wretched … [Hence] the woman who wears out and destroys generations of nursing relatives, and who, as Wendell Holmes has said, is like a vampire, slowly sucking the blood of every healthy, helpful creature within reach of her demands.”22

Mitchell’s views here reveal his own underlying hostility towards his hysterical patients, an attitude that was broadly shared among the “nerve doctors,” but they are also revelatory of some of the secondary gains the hysterical woman might obtain from her symptoms, the shift in the balance of power in the home that illness could license and produce. Misogynistic as Mitchell’s pronouncements may seem to the contemporary reader, they were typical of “informed” medical opinion on both sides of the Atlantic. Henry Maudsley, who ministered to a similarly elite clientele of nervous patients in late-nineteenth-century Britain, was equally outspoken about the dangers of higher education for women. Emphasizing once more that “the energy of the human body [was] a definite and not inexhaustible quantity,” he warned that females on the brink of womanhood could “not bear, without injury, an excessive mental drain as well as the natural physical drain which is so great at that time.”23 Should they seek to do so, the result could only be a multiplication of the number of hysterics and the creation of “a race of sexless beings [who would] carry on the intellectual work of the world, not otherwise than as sexless ants do the work and fighting of the community.”24 Presumably, Maudsley and Mitchell did not anticipate the emergence of a class of female warriors. But they were united in their conviction, as Maudsley put it, that women “cannot rebel successfully against the tyranny of their organization”; they cannot escape the fact that a woman “labours under an inferiority of constitution by a dispensation which there is no gainsaying … This is not the expression of prejudice nor of false sentiment; it is a plain statement of a physiological fact.”25

To be sure, Maudsley and Mitchell, and their fellow specialists, had male as well as female patients, and here, too, wear and tear on the nervous system could produce “disastrous” results. “Neural exhaustion” was particularly likely in early adulthood, and again in middle age, where, at the height of a man’s powers, he might find his brain unexpectedly rebelling, refusing more overwork, and launching him into a career as a hysterical or nervous invalid. Irregular meals, lack of sleep, an excess of blood in the brain, the lack of physical exercise, these and other excesses could sprain the brain. Thus, those “unable or unwilling to pause in the career of dollar getting … making haste to be rich,” were all-too-likely to find themselves “wrecked and made unproductive for years or forever.”26

For male and female alike (though in practice women disproportionately received the treatment), Mitchell prescribed a remedy that followed directly from his diagnosis of the problem. Wear and tear needed repair by building up fat and blood, and that desirable goal could most readily be attained by an extended period of rest and force-feeding. Soon dubbed the “rest cure,” Mitchell’s approach was rapidly adopted as the standard approach to the hysterical and the neurasthenic on both sides of the Atlantic. By its very nature, rest was something only the affluent could afford—not seemingly a problem so long as etiological theories located hysteria and its analogues predominantly among members of the upper classes (though, in reality, hysteria and neurasthenia were surfacing increasingly among the lower orders, a situation neither theory nor therapy made it easy to acknowledge).

“Rest” meant something quite complex in this context. Patients were to be sequestered away from their families, lest well-meaning relatives interfered with what followed. Patients were then confined to bed continuously for weeks at a time, and fed almost continuously with vast quantities of fattening foods. All reading and writing, and other forms of intellectual stimulation, were banned. In place of exercise, patients received massages or electrical treatments to stimulate their muscles and hasten defecation (the better to permit renewed feeding). In the beginning, when “the most absolute rest is desirable, I arrange to have the bowels and water passed while lying down, and the patient is lifted on to a lounge for an hour in the morning and again at bedtime [sic], and then lifted back again into the newly made bed.”27 The inactivity and high-calorie diets often resulted in massive weight gain, something the nerve doctors viewed as a thoroughly satisfactory outcome. Above all, the patient’s will was subject to the imperious commands of her medical attendant—“her” because, as Mitchell himself noted, “for some reason, the ennui of rest and seclusion is far better borne by women than by the other sex.”28

“Rest,” then, “is not at all their notion of rest. To lie abed half the day, and sew a little, and read a little, and be interesting as invalids and excite sympathy, is all very well, but when they are bidden to stay in bed a month, and neither to read, write, nor sew, and to have one nurse,—who is not a relative—then repose becomes … a somewhat bitter medicine”29—one that even the more compliant sex found hard to swallow. But one that worked. The rest cure was, all agreed, the most comprehensive “regular, systematic, and thorough attack” on the problems of hysteria and neurasthenia, especially when those disorders were complicated by a refusal to eat. Physicians all across America, Britain, and continental Europe hurried to embrace its principles.

Sir William Gull, a leading society physician in London had begun to draw attention to emaciated hysterical women as early as 1868, terming their disorder “hysteric apepsia.” An 1873 paper of his relabeled the condition. He now termed it “Anorexia Nervosa (Apepsia Hysterica, Anorexia Hysterica)”30 and it was the first of these terms that caught on. Not surprisingly, Gull was an enthusiast for the rest cure, as were colleagues such as William Playfair, Thomas Clifford Allbutt, and the wonderfully named Thomas Stretch Dowse. When Virginia Woolf had her first breakdown in 1904, her physician, Sir George Savage, subjected her to a mild version of the cure, an experience Woolf, like the American writer Charlotte Perkins Gilman (a patient of Mitchell’s), found intolerable. The enforced infantilization, the absence of all intellectual nourishment or stimulation, the utter boredom, the attempts to suppress their own individuality were a source of horror and wretchedness, vividly represented in Gilman’s short story “The Yellow Wallpaper,” a literary document that ensured that Weir Mitchell’s name would reverberate in feminist circles in our own century as the epitome of the brusque, misogynist, paternalistic Victorian nerve doctor. How most who underwent the treatment felt we cannot know, though, alongside the protestors, other women certainly pronounced themselves grateful for the ministrations of Mitchell and his colleagues, and felt improved or cured by the experience. Was this false consciousness, or perhaps just a demonstration that women, like men, are in substantial measure creatures and prisoners of their culture’s assumptions and prescribed roles?