During the 1940s and 1950s, much of the energy that had animated the experimentation and reform in liberal education in previous decades was siphoned away by the Great Depression, the Second World War, and the associated recovery. Rather than pursuing or debating innovation, advocates of liberal education in the mid-twentieth century were reduced to arguing for survival, because “higher education of any kind, but particularly that which has no specific vocational aim, is always threatened in time of war.”1 Responding to this threat, leaders of “liberal colleges,” such as the President of Carleton College, persistently advocated “The Preservation of Liberal Education in Time of War.”2 In selection #60, President Frank Aydelotte of Swarthmore College elaborates this defense.

Apart from the perception that liberal education has no technical application, another significant factor contributing to the threat was the decline in enrollments in the liberal arts. Young men, who traditionally dominated enrollments in liberal education, were entering the military instead. Yet, this factor presented an opportunity and responsibility for women, suggested the president of Sweet Briar College, because “what women get in their education now may largely determine . . . the ideals and attainments of the next generation. . . . [W]omen, who are not primarily absorbed into war activity, keep alive the long-time values of learning and culture which belong to all generations.”3 Although this aspiration was generally unrealized due to the exclusion or marginalization of women by most institutions that traditionally championed liberal education, the suggestion that liberal education pursued by women during the war would determine that for men after the war was confirmed in a few instances. One such case was the “experimental” liberal education for women instituted at Purdue University between 1939 and 1947, as described in selection #59 by Sarah Barnes.

Meanwhile, the Association of American Colleges (AAC), comprising some 550 institutions throughout the country, issued a report in 1943, “The Nature and Purpose of Liberal Education,” which was summarized in a news release sent to 1,894 newspapers; condensed in a booklet distributed to nearly 7,000 educational organizations, journals, elected officials, and heads of schools, colleges, and universities; and sold, in 6,000 copies, to institutions of higher education, many of which were revising their curricula.4 Despite all this effort, the report exercised little influence, for it drew from nearly every viewpoint arising in the experimentation of the early decades of the twentieth century. In the “nature” of liberal education, the report included physical, intellectual, aesthetic, moral, and spiritual training whose “purpose” was to inculcate individual freedom, personal fulfillment, intellectual discipline, and social responsibility, as well as the “skills and abilities . . . to use intelligently and with a sense of workmanship some of the principal tools and techniques of the arts and sciences.”5

This eclecticism was no embarrassment to the Commission because the tendency to blend and reconcile different viewpoints characterized many statements on liberal education during the middle of the twentieth century. The earlier, distinctive proposals from Progressive Colleges or Robert M. Hutchins gave way to eclectic statements, such as General Education in a Free Society, a report of a committee of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Harvard University. Declaring that “general and liberal education have identical goals,” General Education in a Free Society endorsed conviction while respecting tentativeness of conclusions, honored heritage and tradition while admitting a modern emphasis on process and change, recommended “unity conditioned by difference,” promoted “tolerance not from absence of standards but through possession of them,” and reconciled “Jeffersonianism and Jacksonianism.”6 Though the “now famous Harvard report” attracted a great deal of comment,7 it was never adopted by the Harvard faculty and widely thought to be self-contradictory or unsystematic.8

Amid this eclecticism, the most significant innovation appearing in the middle decades of the twentieth century was the introduction of honors work. The honors idea recalled the critique of democratic culture associated with John Erskine’s strain of Great Books, as discussed by Daniel Bell in selection #54. But the leading spokesman for the full-fledged movement in subsequent decades was Frank Aydelotte, whose explanation and justification for honors study is found in selection #60. Honors work thus became the most innovative aspect of “the emerging curricular blueprint devot[ing] the first two years of the undergraduate course to general education in fundamental liberal arts subjects and the last two to more specialized, often frankly professional, training,” in the words of Willis Rudy. This blueprint, described in selection #61, was instituted throughout the country between 1925 and 1960.

The following two decades presented “as volatile a period of educational reform as America has ever experienced,” including widespread social and political protests on American campuses.9 Amid that upheaval, some reformers attempted to tear up the curricular blueprint and radically reform liberal arts in the United States. The conceptual relationship between liberal education and liberatory movements, including political or social liberalism, is debated by Harold Taylor and Paul Kristeller in selections #62 and #63. The prominent attempts at curricular reform are analyzed by sociologists Gerald Grant and David Riesman in selection #64.

Between 1939 and 1947 an “experiment” in liberal education was conducted at Purdue University, one of the land-grant universities that was founded under the Morrill Act of 1862 and dedicated to providing training in “agriculture and the mechanical arts.” The Purdue experiment was not only to offer liberal education, but to offer it to women. The stimulus to attempt either venture arose out of the upheaval and reorganization caused by World War II. Due to its success, the experiment was ultimately co-opted by men. Nevertheless, the women’s program determined post-war liberal education at Purdue, and thereby demonstrates that “women were sometimes at the center, rather than on the periphery, of fundamental developments in liberal education,” as discussed in selection #59.

Among the 109 women who completed the program in “Liberal Science” was Virginia MacDonald Menke, whose reflections provide some of the data for this selection. Menke’s daughter, Sarah V. Barnes, is the author of this selection. Born in Wisconsin in 1961, Barnes’s interest in the topic was peaked partly by the experience of her mother, but also by her undergraduate studies at Williams College, which, she says, “kindled my profound belief in the value of a liberal education.” After graduating with a B.A. in history in 1984, Barnes studied at Northwestern University, completing a Ph.D. on the comparative history of Modern Britain and the United States. She has taught at Northwestern University, Southern Methodist University, University of Colorado, Colorado State University, University of Hong Kong, and Texas Christian University. She is now a professional horse trainer in Colorado. Citations have been excised from this selection, except for quotations.

A female student entering Purdue University in the late 1930s found her options rather limited. If not one of the two or three women to enroll in Engineering or Agriculture, she could either join the majority of her peers in the School of Home Economics or tackle a technical degree in Science. For President Edward C. Elliott and a handful of others on campus, this was a less than satisfactory state of affairs. . . . As was true of other land-grant institutions, the university’s historic mission to offer training in “agriculture and the mechanical arts” dictated a commitment to providing the citizens of the state, men and women alike, with preparation for careers in an expanding array of scientific and technical fields. The university’s aim for its male students seemed clear: equip them to be scientists and engineers. But as the number and variety of employment options for women began to increase, and as more and more female students arrived on campus, not all of whom sought highly technical careers, or careers at all for that matter, nor wished to major in home economics, administrators struggled with how best to prepare these young women for the future.

At the same time, the perennial debate about the broader purposes of higher education within American society was in the midst of a particularly contentious phase. Faced with rising enrollments and the arrival on campus of an increasingly diverse and vocationally-minded student body, individual institutions sought some effective means of reconciling an ever-more specialized and fragmented curriculum with the traditional claims of the liberal arts. Even at Purdue, the long-standing land-grant commitment to training scientists and engineers began to seem problematic. For many schools, the solution appeared in the form of general education, an approach which aimed to provide students with a broad foundation of cultural knowledge before allowing them to equip themselves with the specific skills needed to earn a living.

Amid these contentious debates, a unique program for female students flourished at Purdue from 1939 until 1947. Beyond recovering some memory of the program’s existence, one purpose in recounting the story is to add to our understanding of the experiences of women in liberal education during a period of unusual opportunity that soon passed. In addition, this story illustrates that women were sometimes at the center, rather than on the periphery, of fundamental developments in liberal education and it is important to recognize the significance of their presence.

Purdue in the 1930s did represent, in many respects, the typical Midwestern land-grant institution. Like its regional neighbors Iowa State and Michigan State, the university—located in West Lafayette, Indiana, along the banks of the Wabash River—concentrated primarily on instruction in engineering, agriculture, and other vocational subjects. Hoosiers seeking a less technical degree went either to Indiana University in Bloomington or to one of the state’s numerous small private liberal arts colleges. Undergraduate enrollment was rising throughout the second half of the decade, from 4,381 in 1935 to 6,669 in 1939, as the economy recovered from the Depression and higher education became more and more central to American life.

Not surprisingly, men outnumbered women at Purdue by more than four-to-one.11 Yet although always a distinct minority on campus, the number of women attending Purdue during these years increased in both absolute and relative terms, from 744 or 17 percent of the student body in 1935, to 1,272 or 19 percent in 1939. More than two-thirds of these women graduated from the School of Home Economics; most of the rest, slightly more than a quarter, earned B.S. degrees from the School of Science, while the majority of the remainder graduated in pharmacy.12 Of the men, two-thirds earned engineering degrees; the rest were mainly in either agriculture or science, with a handful in pharmacy. Of the largest divisions on campus—Engineering, Agriculture, Science and Home Economics—only the School of Science enrolled a substantial number of both male and female students. Here the ratio was approximately two-to-one.

As was true of Purdue’s other schools, the School of Science concentrated on preparing students for technical or teaching careers, in this case primarily in the fields of chemistry, physics and biology. In addition, Science provided a home for the departments of English, Mathematics, History, Government, Economics and Modern Languages, whose collective purpose was mainly to offer basic courses required by the other schools for graduation. In addition to a minimum of such general requirements, graduation from the School of Science itself involved numerous hours of laboratory work in the hard sciences, even for those students seeking careers in a non-technical field. Restricted by a “gentleman’s agreement” with Indiana University, Purdue at the time offered only B.S. degrees.

Thus, a female student entering the university in the late 1930s found her options limited, particularly if she did not want a degree in home economics. Administrators were not unmindful of the dilemma. President Elliott, himself the father of two teenage daughters, demonstrated his concern in a number of ways, including two significant faculty appointments, both made in 1935. . . .13 One was Amelia Earhart, who made several trips to Purdue over the course of the 1935–36 academic year, living in the women’s residence hall, meeting with students, and generally causing quite a stir on campus during her stays. Besides inspiring Purdue’s co-eds to flaunt fashion etiquette by wearing slacks in public, she challenged them to believe in their potential as women to succeed at a wide range of vocations. Meanwhile, with the help of Purdue engineers, she prepared for her ill-fated flight around the world.14

Perhaps less newsworthy but of more enduring significance was Elliott’s other major female faculty appointment, Lillian Moller Gilbreth. With a Ph.D. in psychology and a successful career as an industrial engineer, Gilbreth joined Purdue’s engineering faculty in 1935 as a visiting full professor, a position she retained until 1948. While her interactions with students in this capacity involved men as well as women, she was always especially supportive of the handful of women in Purdue’s engineering program, as well as female students generally. As the only female full professor outside of the School of Home Economics who was not primarily serving in an administrative capacity, she represented an important role model.15 In particular, she influenced many female graduates of Purdue to pursue careers in industrial management and personnel.

Yet while the presence on campus of these two accomplished women reflected President Elliott’s efforts to foster a positive atmosphere, difficulties remained. More and more women were coming to Purdue, but not necessarily because of its reputation in agriculture, engineering, science, or even home economics. Some were the daughters of faculty or alumni, others had older brothers already enrolled, some were simply from West Lafayette and wanted to attend school close to home. Whatever the reason, they arrived on campus but found little in Purdue’s existing curriculum that appealed to them. Dean of Women Dorothy Stratton in particular lamented the university’s lack of a bachelor of arts program, which she felt would have served the needs of this growing population. At her urging, President Elliott in 1937 appointed a committee to consider the problem.16

Over the course of the next two years, the Committee on the Education of Women met under the leadership of Helen Hazelton, professor and head of women’s physical education and, like her colleague Dean Stratton, a forceful and articulate advocate of the interests of female students.17 The committee’s first report, submitted in February 1938, began by dividing the question under consideration into three areas: 1) the problem of training for vocations, 2) the problem of training for marriage and family life, and 3) the problem of the kind of general education appropriate to women students. . .

In reference to “that possibly increasing group of women who are not particularly concerned with a specific vocation, but come to Purdue for a general education,” the committee asked, “What education should they have that will fit them to be intelligent members of the community and, what is more important, give them the background of personal culture, in the broadest sense?” Noting that many of these students ended up in the School of Science, where they were frustrated by required laboratory classes designed for specialists, as well as by the lack of a broad range of courses in the humanities, the committee bluntly observed “that what many of these women students seem to want is, in good part, the subject matter commonly associated with the B.A. degree.”18

Purdue could not offer a B.A. because of its agreement with Indiana University, but the committee did not consider advising these women to go elsewhere. The reasons for this were probably threefold: 1) the women were there already, drawn by family ties, convenience and cost; 2) Purdue wanted to do more for women students generally; and 3) adapting the curriculum promised to attract larger numbers of women to the university. Given the heavily skewed gender ratio, the economics of increased enrollment and the fact that every high school graduate from the State of Indiana, male or female, represented a potential Purdue student, finding a way to attract more women constituted a reasonable priority. . . .

The committee proposed combining two years of general education in the School of Science with further specialized work in whichever departments of the university would best serve the individual student’s vocational ambitions. Instead of meeting the traditional freshman and sophomore requirements in the School of Science, the women would enroll in a specially planned series of four survey courses in physics, math, chemistry and biology aimed at presenting science as an area of knowledge and inquiry rather than as a basis for technical skill. . . . A fifth survey, devoted to the history of civilization, would serve in similar fashion to introduce the fields of knowledge covered by the social sciences and humanities. Finally, the committee proposed fewer credit hours be demanded for graduation, allowing students to devote more study time to the surveys and later to pursue specialized subjects in greater depth. . . .

Consequently, as the statement on the proposed curriculum concludes, “it was agreed that these new courses should first be given to an experimental group and that this procedure be considered as an experiment.”19

Accordingly, in April of 1939, the university’s Executive Committee approved the recommendation of the Committee on the Education of Women that a group of about forty young women be permitted to register in the School of Science, that survey courses as outlined in the committee’s report be established for this group, and that a qualified female faculty member be hired to direct the program and act as an advisor to the students. Assured by President Elliott of the administration’s moral and financial support, the committee began to prepare for the arrival of the program’s first class of students in September.

Despite its small number, the group’s presence on campus was portentous, marking a trial effort at serving students with a different set of needs than Purdue was accustomed to accommodating. Although sponsored by a committee ostensibly concerned only with the education of women, the program symbolized an attempt to widen and shift the mission of the university as a whole, with ramifications for students of both genders. As demonstrated by the committee’s difficulty in confining itself to its stated mandate, the issue of general education and the problems involved in the education of women proved virtually inseparable, particularly within the context of a traditionally male-dominated, technically-oriented land-grant university.20 Herein lies much of the significance of Purdue’s experimental curriculum.

In addition, particularly for the actual women involved, the program’s significance lay also in its implications for their own educational experience. Between 1939–40 and 1946–47, the last year in which only women were admitted, 109 students completed the experimental curriculum. As a whole, they were a select group, chosen on the basis of outstanding high school records, test scores and recommendations, as well as personal interviews. Dean Stratton, Prof. Hazelton and Prof. Dorothy Bovée, who arrived half-way through the first year to direct the program, were determined to admit only young women capable of meeting the rigorous academic standards which they felt must be maintained if the program were to prove its educational worth.21 The students themselves, referred to in campus publications as “the guinea pigs,” chose the experimental curriculum primarily because it offered a distinctive approach to education in the sciences, as well as the opportunity to take a broad range of classes from any school in the university. Most were explicitly not interested in home economics or technical scientific training, yet had other reasons for attending Purdue, including family connections and financial considerations. Others who wanted a liberal education and normally would not have considered Purdue, learned of the curriculum and decided to attend. Clearly, then, the program was serving the constituency for which it had been planned.

Once enrolled, the women’s response to the experimental curriculum was overwhelmingly enthusiastic. The survey courses, they found, were both challenging and stimulating, taught by outstanding faculty members who welcomed the chance to develop the new courses and work with a group of such able and dedicated students. The professors themselves seemed curious about how the young women would react to the material, which presented fundamental scientific principles from an historical and philosophical perspective, and then raised questions about the role of science in contemporary life. Yet while they might have been unaccustomed to classrooms full of female faces, the science faculty involved in the program clearly respected their students’ intellectual capacities and expected them to use their minds. . . .

Above all, students in the experimental curriculum were encouraged to think of themselves as leaders—leaders with an awareness and understanding of the critical role of science in modern life, a clear perception of present-day social, economic and political problems, and the resolve to confront and solve those problems in an objective and democratic fashion. In the words of an alumna, “while statistics said that somewhere around 95 percent of us would marry and stay home to rear our children, the Liberal Science environment told us we were valuable citizens and just as important to society as any man on the engineering campus. . . .”

Certainly the women in the program felt special. As one of them recalled, “my classmates were the cream of the crop. . . . We had the very best professors, small classes, could head in our own directions academically after studying the broad core curriculum.” “It was like being in a small college inside a huge university,” remarked another. Competition among the guinea pigs could sometimes be fierce, as everyone strove to do well in demanding classes, but mainly the women felt privileged to be part of a rather elite group. If they did perceive any obstacles as women at Purdue, it was only in their junior and senior years, when they found themselves in upper-level courses surrounded by male students and taught by a different set of male professors, some of whom were unaccustomed to sharing the classroom with such sharp and self-confident co-eds. More often than not, however, the women were unaware of gender discrimination in the classroom, and continued to compete and succeed academically alongside their male peers.

They also participated avidly in a wide range of student activities, from sororities to student government to the year book and newspaper, and in this manner were part of the regular student body. . . . Nevertheless, throughout their time at Purdue, women in the experimental curriculum consistently earned top scholastic honors and also tended to be over-represented in the leadership positions of various extracurricular activities, indicating the degree to which they were indeed a special group, both inside the classroom and out. . . .

Following graduation, many of the women did go on to pursue a variety of careers for which the program’s combination of liberal education and vocational training had prepared them. In 1948, a survey of the first 109 graduates found 20 had gone on to graduate school, 14 were teachers and 13 were in personnel or industrial management (reflecting the influence of Lillian Gilbreth). Of the remainder, most had jobs in a wide variety of fields ranging from journalism, radio, and advertising, to social work, business, law, and scientific and economic research. Of course in 1948 many of these women had only been out of college for a few years, and many subsequently left their jobs to raise families. Nevertheless, as another survey conducted in 1996 revealed, many alumnae of the experimental curriculum either combined work and family throughout their careers, or returned to work later in life. . . .

Judging from the experiences and testimony of these women, then, the experimental curriculum seems to have been a success. Its goal, “to train select groups of young women for intelligent leadership in whatever communities, large or small, urban or rural, they may be placed after college,” was surely met. Nonetheless, by the fall of 1947 the focus of the program was beginning to shift. Indeed, some changes had already been made as early as 1944–45, when the experimental curriculum officially lost its “experimental” designation and became known instead as “Liberal Science.” In the same year two new required courses, open only to Liberal Science students, were added. The first, entitled “Science and Technology in Present-Day Life,” was to be taken junior year. The second, open to seniors, was “Women and Women’s Work.” . . .

Liberal Science was increasingly becoming recognized as a distinctive program within the university. Indeed, the Liberal Science curriculum, with its selective standards for admission, small class sizes and demanding courses, opportunities for individually-directed work, outstanding faculty and stellar students, had begun to take on the characteristics of a four-year general education honors program.

Given the experiment’s success, it is perhaps not surprising that the decision soon followed to admit men. The first group, selected according to the same criteria as the women, joined the program at the beginning of the 1947–48 academic year. Undoubtedly many factors were involved in the change. First, from a philosophical standpoint, the Committee on the Education of Women, which originally developed the experimental curriculum, had always believed the program’s objectives and methods applied to men as well as women. From the beginning, the experiment was viewed as one in which the results might eventually become more widely applicable. Secondly, from a practical standpoint, Purdue by 1947 was being overrun with veterans returning to college on the G.I. Bill. The School of Science was particularly taxed by the jump in enrollments, not only because of rapid growth within the school itself, but because students in all the other schools in the university took at least some courses in the School of Science. Indeed, Liberal Science was the only department within the School of Science not offering at least one course required by another school. Under the circumstances, maintaining an elite and rather expensive program in the sole interests of a small group of women students, however smart, seemed hard to justify. Finally, male students were clamoring to get in. In the words of one of the last women to go through the program before it was integrated, “the men saw they were missing a good thing.”

The admission of men, however, was only the beginning of fundamental changes in the status of “Liberal Science” at Purdue, changes which were tied not to the special interests of women but instead to major post-war imperatives affecting all of American higher education. The land-grants, in particular, faced a major reassessment of their mission in the wake of the shattering experiences of a war between democracy and totalitarianism, in which technological capacity seemed to have so far outstripped moral judgment. Even before the war, land-grant leaders had begun to question the impact of proliferating course offerings and increasingly fragmented curricula, so that the experience of war itself only added to concerns about their institutions’ tendency to produce narrowly specialized scientific knowledge at the expense of a broader understanding of basic human values. . . .

For Elliott, an educational program designed particularly to meet the needs of women served the wider purpose of helping to elevate Purdue’s status as a “true university,” meaning an institution committed to some form of liberal learning, as well as to its historic mission of scientific and technical training. The role of gender as an agent in redefining the university’s identity in these terms was instrumental. Women were literally the guinea pigs. Yet extending the results of the experiment beyond the laboratory remained a problematic process, not least in regard to its implications for the guinea pigs themselves.

It was a problem with which Purdue officials began seriously to grapple during the early years of the war, when a committee was established to consider the “Functions of the University in the Post-War World.” . . . Seeking to clarify the goals of the new curricula, the committee went on to list eight major objectives of general education, including: 1) the ability to read with understanding and to express thoughts clearly and accurately in oral and written English; 2) an understanding of the major factors in the historical development of American institutions and international relations; 3) an understanding of the major phases of contemporary social and economic life along with the ability to read with discrimination and to arrive intelligently at opinions on social and economic problems; 4) an understanding of human behavior as a means of attaining a) sound personal adjustment and b) the ability to deal intelligently with problems of human relationships; 5) an appreciation of the major forms of expression of the culture as evidence in literature, the fine arts, and music; 6) an understanding and appreciation of the basic principles of science, the scientific method, and the part science and technology play in the modern world; 7) the understandings and abilities necessary to maintain health and physical fitness on both an individual and community basis; and 8) an understanding and appreciation of the ethical and social concepts necessary for a satisfying personal philosophy.22

Fulfilling these objectives, in the committee’s view, was central to the mission of American higher education in the post-war world, especially at the land-grants. . . . Beginning in the fall [of 1947], all entering students were to meet a series of core requirements consisting of specified courses in the sciences, humanities and social sciences. . . . Although the report spoke of such courses as being in the process of development, with no mention of the existing Liberal Science curriculum, the assignment of course numbers, as well as the catalog descriptions, indicate the “new” survey courses were simply taken over from Liberal Science. . . .

A comprehensive program in general education which in effect fundamentally transformed the character of the university was thus built upon the foundation provided by the Liberal Science curriculum for women. In the process, however, many of the curriculum’s unique features, particularly those which made it most valuable to women, were lost. These included a female academic administrator devoted particularly to the interests of female students. Not long after men were admitted to the program in 1947 and just as the curriculum revision process in the School of Science was getting underway, the director of Liberal Science, Dorothy Bovée, resigned. . . .23

The values of general education thus gained ascendancy within Purdue’s School of Science, yet at a price. Women qualified for the Liberal Science program lost not only an advocate, in the person of Dr. Bovée, but also the opportunity to enroll in demanding classes composed of above-average students who were expected to excel regardless of gender. Indeed, to the extent that Liberal Science functioned in its last year as an honors program for both men and women, its demise represented a loss for any student in the School of Science capable of exceptional achievement. This fact was recognized by members of the university’s Committee on Students of Superior Ability, who campaigned for the program’s preservation while questioning the ability of the average Purdue student actually to benefit from the type of courses instituted under the revised curriculum. . . . [H]owever, the expression of such views merely provoked a hostile response from those who viewed them as symptomatic of an academic elitism which had no place at Purdue, given the land-grant institution’s populist ethos. . . . Unfortunately for talented women, of whom little enough was often expected anyway, supplanting Liberal Science with general education meant that the affirmation involved in being selected to participate in an elite program, along with the liberating effects of the educational experience itself, were both sacrificed.

Raised in Indiana, Frank Aydelotte (1880–1956) earned a B.A. from Indiana University in 1900; and, after teaching English in college for two years, completed an M.A. in English at Harvard University in 1903. He then taught for two more years at Louisville Boys High School in Kentucky, and was named a Rhodes Scholar in 1905 to study at Oxford University. In 1907 Aydelotte married and therefore had to resign the scholarship, but he remained at Oxford to complete the B.Litt. in 1908, at which point he became Associate Professor of English at Indiana University. He was named professor of English at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1915 and acquired a national reputation through his work with the Rhodes Trust. In 1921 he accepted the presidency of Swarthmore College, a small relatively undistinguished institution that had been founded by Quakers. In selection #60, Aydelotte describes his arrival at Swarthmore and the genesis and nature of the honors work that earned Swarthmore renown and stimulated a national movement in liberal education.

Although Aydelotte attributes the origins of his own conception of honors education to the colleges of Oxford, the selections in Section VIII indicate that certain American movements informed honors work in the United States. The focus on elite intellectual education had precursors in John Erskine’s honors seminar in great books at Columbia University, as well as in the commonly expressed view in the 1920s “that more colleges should adopt a rigorously selective plan of admission, because too many persons are going to college.”24 In addition, the honors impetus toward individual autonomy, personal fulfillment, and opposition to regimentation were rooted in educational Progressivism. Hence, when the Master of Balliol College, Oxford, visited Swarthmore in 1930, “what struck him about our honors plan was not so much its resemblance to Oxford as its differences.”25

In 1939, his last year at Swarthmore, Aydelotte began to write a summative book reporting developments in honors work occurring at 130 colleges and universities throughout the country. By the time Aydelotte completed the book in 1943, he observed that “many plans for honors work have had to be curtailed or suspended because of the war and the absorption of college faculties in the educational programs prescribed by the Army and Navy.” (p. xiii.) With this in mind, Aydelotte wrote the first chapter addressing the preservation and role of liberal education in a time of war. Meanwhile, in 1940 Aydelotte had resigned the presidency of Swarthmore to become the second director of the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, NJ. He succeeded Abraham Flexner (1866–1959), the prominent commentator, researcher, and reformer of education, who had known Aydelotte since they taught high school together in Louisville, Kentucky. After a turbulent tenure as Director, Aydelotte retired in 1947 and died in Princeton, NJ, in 1956.

All times of strain, such as war or depression, tend to shake men’s faith in liberal education. When danger threatens, competence to perform immediate practical tasks is at a premium and the expert takes precedence over the philosopher. Freedom of the mind then seems less useful than the habit of faithfully obeying instructions. Defense calls for efficiency. Too much emphasis on freedom of thought and the unrestricted development of the individual seems to make society less efficient, more wasteful of human resources, less manageable, less subject to planning and discipline. The miraculous achievements which flow from individual initiative and free enterprise are, when all is said, unpredictable, and do not appeal to men who, in the face of catastrophe, desire above all else to be secure. On the other hand, the very foundation of our democracy is our conception of liberal education and the freedom of the mind which that implies. Upon the broad liberal training of youth in our high schools and colleges our future will depend. This fact is widely realized and it is not surprising that men everywhere are discussing anxiously in these days the future of liberal studies.

There is another subject, however, about which men in general are even more anxious; that is security—military security, political security, and economic security. Not merely the war, but also the depression which preceded it, show how fragile is our twentieth-century civilization and how easily our supposedly inalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness may be swept away. The soldiers and sailors and aviators who are fighting this war and the laborers who are supporting them at home will demand as their reward security not merely against military aggression, but also against unemployment.

There is a real conflict between these ideals. Liberal education is an adventure, both for the individual and for society: for the individual because its first aim is not to enable a man to make a living but rather to teach him how to live; for society because when able young men and women are trained to think for themselves and are left in freedom to do so, no one can predict the result. Security in war and prosperity in time of peace seem, on a superficial view, to depend more upon technical training than upon liberal knowledge.

Some degree of regimentation in war time is inevitable. Education is perforce restricted and it is the liberal element which is the first to be curtailed. That fact is strikingly illustrated by the changes brought about in American education by the present war. College students are called into military service often before their higher education is more than well begun. For those that remain programs must be altered in accordance with military needs. In the curricula prescribed by the Army and Navy there is and must be strong emphasis upon technical subjects at the expense of liberal studies, and this fact has aroused widespread apprehension as to the future of the liberal college. The cruel test of war brings out in sharp relief what seem to be the manifold inefficiencies of liberal education.

This is a war of physicists and engineers. The day has gone by when it was sufficient training for a soldier to teach him to shoot straight with a rifle and lunge effectively with a bayonet, to develop his physical strength and courage, and to give him the discipline needed to make him behave well in combat. The soldier of today must learn to handle intelligently many kinds of intricate mechanical devices. He must be a specialist in the operation of tanks, airplanes, artillery, radio, and other precision instruments of great complexity. He needs at least an elementary understanding of mathematics, physics, navigation, meteorology, and other scientific subjects. The training of soldiers and sailors demands vast schemes of practical scientific and mechanical instruction.

The manufacture of the implements of war likewise calls into play all the resources of our physicists, chemists, engineers, inventors, and skilled mechanics, and all the resources of industrial management. Never before in history have we had so close a relationship between abstruse theoretical research by the physicist in his laboratory, scientific mass production of heretofore unprecedented accuracy, and practical use of scientific instruments of warfare on the battle field, on the high seas, and in the air above. Our strength in battle seems to depend not so much on broad liberal education as upon highly specialized technical skill.

The question has arisen in many minds whether the postwar period, which will confront us with a different though no less severe test, may not produce a similar demand for the revamping of our entire educational program along more practical lines.27

In the first place all the accelerated scientific discoveries and mechanical improvements made under the stimulus of war will contribute to the amelioration of human life in time of peace. Nothing is more fascinating than the romantic predictions, which sound like fairy tales but which will doubtless some day be sober reality, of the marvelous gadgets we shall all have to play with when the war is over, and we are able once again to beat our scientific swords into mechanized and automatic ploughshares. There will be no end to the wonderful toys and useful tools which we shall make out of the newly developed instruments of war-tanks, battle planes, radio equipment, new alloys, and plastics. Health will be improved and sickness eased by new discoveries in connection with nutrition and newly developed medical and surgical techniques. All of these contributions to human welfare depend upon science and technology and will inevitably enhance the importance of technical training in the post-war world.

In the second place there are signs which point to a parallel enhancement of the importance of the techniques of the social sciences, especially economics. The last quarter of a century has been a period of daring economic experimentation in many countries. War and depression have revolutionized traditional methods in public finance and private trade. Economic problems—unemployment, social security, international trade and finance—have become increasingly technical and complex. They are in many respects too difficult for the layman and tax the knowledge of the expert. The so-called brain trust is the logical answer. Governments and large industrial organizations depend more and more upon expert knowledge in the fields of trade and finance just as they have done in the past in the field of public health.

The war has witnessed for the first time in history the mobilization of the total economic strength of all the great nations engaged, at the price, for the most part willingly paid, of national regimentation and the substitution of specialized technical training for broad liberal education. The question inevitably arises whether this strength cannot similarly be mobilized for the purpose of realizing peaceful ends, to free the world from want, and whether if this is done it will not demand similar regimentation and similar emphasis upon technical skill at the expense of liberal values.

It is such considerations as these which cause men to fear that this war may mark a turning point in the development of our system of higher education, away from the liberal arts to technical training of experts in the natural and social sciences. Men fear that nations and individuals in the post-war world will be so poor, will feel so insecure, that they will be compelled to study how to get a living at the expense of how to live. The demand for security—economic security, political security, and what one might call ideological security—will be strong in this and every other country. We shall be in danger, in the search for security, of curtailing the life of freedom and adventure which is the condition of all high achievement. It is not only in the sphere of politics and international relations that timidity is fatal and “security mortal’s chiefest enemy.”28 It may be also that weariness and want will make men and nations fearful of freedom of economic enterprise, freedom of scientific invention, and freedom of speculation in the realm of pure intellect. Regimentation of the human spirit in one direction may lead to its regimentation in all forms of activity. . . .

One cannot but feel that such a shift in emphasis in our education would be a moral and spiritual calamity, that no measure, however full, of material comfort and security would justify. Even if human life has been insecure—solitary, nasty, poor, brutish, and short,29 it has been better than the life of Leacock’s man in asbestos.30 To abandon the ideals of liberal education would mean that in winning the war we had given up all that we are fighting for, and it would be furthermore a tragic misreading of the lesson which we ought to learn from the issue of the conflict. This war is a contest between individualism and totalitarianism. And just as freedom and individualism, despite a late start and despite many errors and inefficiencies, are now beginning to show themselves strong enough to prevail in the struggle, we may hope that they will be strong enough to prevail in the post-war world. We must not allow ourselves to forget that freedom—political freedom and freedom of the mind—has been our greatest asset in the present war. The totalitarian powers had a long start in technical preparation. What they do not have and cannot develop is the courage which free men show in meeting adversity and in struggling against odds. The problems of the war and of the peace are fundamentally not technical but moral, philosophical, and religious. They can be solved only by men into whose education has been infused a liberal element which makes the man so trained, not a mere tool ready to be turned to the service of any power above him, ready to do his job regardless of whether the consequences of his work are good or evil, but rather a thinking being, a citizen, morally responsible, who will take into consideration not merely means but also ends.31

It is upon these considerations that we are entitled, in my opinion, to put our faith in the continuity of the liberal tradition.32 No abstruse arguments will be needed to drive home that point. The lesson will be plain for all to read. We may even expect in the enthusiasm of victory a reaction in the direction of those liberal studies which alone can give victory its true meaning and guide us in the building of the brave new world of our dreams. It is not without significance for the future that many college professors find that their Army and Navy students are keenly interested in those liberal subjects which have been included in the military curriculum. But this is not the time for those of us who believe passionately in the value of liberal studies to be complacent. It is rather a time to examine critically our whole plan for liberal education, to define our aims, to abolish the wasteful and stupid routines which are sometimes the product of traditional methods too long continued, and to avoid, on the other hand, the fads and aberrations into which men fall in the mistaken belief that any change is an improvement. If our liberal education is to meet the needs of the post-war world we must clarify its aims and improve its quality. Energetic and effective efforts to do both have been the most encouraging fact of our educational situation during the last twenty years. As to aims, it is already becoming clear that the central purpose of liberal education cannot be restricted to the study of any particular subject or combination of, subjects. It is not a problem of requiring every student to take courses in Latin and Greek. Nor is it a problem of resisting the claims of science, which for students with any aptitude for it must be an important ingredient in the liberal education of the future. Liberal knowledge is not a formula; it is a point of view.

The essence of liberal education is the development of mental power and moral responsibility in each individual. It is based upon the theory that each person is unique,33 that each deserves to have his own powers developed to the fullest possible extent—his intellect, his character, and his sensitiveness to beauty—over against merely learning some useful technique.34

There is no such sharp distinction between liberal education and technical education as prejudice, even learned prejudice, sometimes believes. Instruction in the plays of Shakespeare may be strictly technical, while electrical engineering or law may be liberal, according to the point of view from which each is studied. An educational system based on belief in the value of liberal knowledge will infuse a liberal element into all training, even the most technical, while exclusive preoccupation with techniques, with means as opposed to ends, may deprive the study of literature, or philosophy, or history, or religion, of any liberal element.35

When peace comes the need for making the most of our best brains for the service of democracy will be not less but more insistent than ever. The tasks which will confront this and every country will be unprecedented in their difficulty and importance, and in the performance of these tasks we shall have to face the choice between regimentation and the voluntary efforts of free men and women. We must choose between the calculable but mediocre results of planning imposed from without and the brilliant but incalculable results of individual initiative working in freedom.

Only our best brains and our highest idealism, trained in freedom and working in freedom, can solve the appalling economic and political problems which we shall face. The democracies have for a long time failed to build into their institutions of government and industry the best ideas of their ablest thinkers. They have not always done so even in education. They must do so in every department of the democratic way of life, if that life is to persist. No merely defensive attitude will meet the need. Only by a democratic attack, worldwide in scope, as daring as are the dreams of the dictators, upon the evils of ignorance and selfishness and want, can the world be made a fit place to live in. Such an attack must involve the public spirit which places the common welfare above private ends in time of peace, as men so naturally do in time of war. It must be as intelligent as campaigns of conquest are stupid. Its aim must be to utilize the resources of nature and the achievements of science to raise the standard of living, material and spiritual, everywhere, and to utilize the resources of intelligence and good will to deal justly with all men and nations. Civilization in one country or one part of the world is meaningless unless its aim is to make all men civilized. Modern industry has unified the world, modern science has made all men neighbors, and we are false to all our ideals unless we treat them as such. This war will mark the beginning of a new and better age than we have ever had before or it will mark the beginning of the end of our civilization. . . .

If we strive, as we must, to realize these high aims, we can do so only by improving the quality of the liberal education offered in our high schools and colleges. The greatest defect of that education is the regimentation of individuals of different levels of ability into the same program. We offer to our students in high school and college bewildering freedom as to the subjects they should study. But once they have made their choice we set up a common standard of achievement for the poorest, the average, and the best. The converse of this policy would produce better results. With some knowledge of the ambitions and aptitudes of a given individual, older heads may well be wiser as to the subjects which he should study. But once the plan of study is determined it is obvious that, each individual should be required to come up to the highest standard of excellence of which he is capable.36 This can never be the case if individuals of all levels of ability are taught in the same classes and set the same examinations. That is the common practice. It constitutes a kind of academic lock step, bad for the poorest and wasteful for the best. We must eliminate that waste if we are to have a liberal training adequate to the needs of the post-war world. While seeing to it that individuals of each level of ability have the training best suited to them, we must realize that the future of our country depends upon what happens to the best. It is from the ablest young men and women, given the proper training, that we may hope for the leadership without which democracy cannot survive.

The immense increase in the enrollment in high schools and colleges at the end of the last war first made educators generally aware of the vast range of individual differences. As a result, during the last twenty years energetic and promising measures have been taken to make education individual and selective. Following the example of the English universities, whose greatest contribution to democratic education is a workable solution of this problem, most of the leading colleges and universities of the United States have put into operation programs for students of unusual ability and ambition which, instead of holding them back to the average pace, allow them to go forward as far and as fast as they can. . . .

It requires courage in a democracy like ours, which considers each man as good as his neighbor, if not a little better, to put into operation what seems to many an aristocratic method of education. But we must learn to see the error in that superficial interpretation of democracy which assumes that all men are equal in intellectual ability. We must understand that in recognizing individual differences we are paying the truest homage to the worth of all individuals.37 Universities and colleges and schools which are today facing the problem of giving to undergraduates of each level of ability opportunities suited to their needs are fulfilling their function in our democracy. They are keeping up their communications with the future. They are ensuring the training of citizens who can make their greatest contribution to all the offices of peace and war, whether as loyal followers or as leaders of courage and insight. The ideal for democratic education good enough to meet the needs of the post-war world must be not security but excellence.

American students are as individuals extraordinarily free. They have their own self-government associations, they manage their own college activities, they take almost complete responsibility for their personal conduct. But the methods of mass education, which are all but universal even in small colleges, effectively deny them the opportunity of taking the same kind of responsibility for their intellectual development. The system of instruction which forms the subject of this book might be described as an extension of undergraduate freedom from the personal to the intellectual sphere. It is essentially a system for selecting the best and most ambitious students, prescribing for these students a more severe program than would be possible for the average, and allowing them freedom and opportunity to work out that program for themselves.

The instruction of the average American student has been standardized beyond the point where uniformity has value. This is perhaps the natural result of the immense increase in numbers of college students during the last half-century. We have in our colleges and universities as many students as we had in the high schools two generations ago. The standardization of the instruction of these masses has been carried to a point where it resembles the Federal Reserve system. If a student has a certain number of hours of academic credit in a certain recognized college, he can cash in this credit at any other recognized college just as he might cash a check through a Federal Reserve bank. Intellectual values cannot be correctly represented by this system.

The system assumes that all college students are substantially alike, that all subjects are equal in educational value, that all instruction in institutions of a certain grade is approximately equal in effectiveness, and that when a student has accumulated a certain specified number of credit hours he has a liberal education. All these assumptions are of course false.38 All courses of instruction are not equally effective; all subjects are not equal in educational value; our students are extraordinarily different in their interests and intellectual capacity; and it is only by qualitative, not quantitative, standards that liberal knowledge can be recognized and measured.

Our ordinary academic system is planned to meet the needs of that hypothetical individual—the average student. It does not pay him the compliment of assuming that his ability is very great or that he has any consuming interest in his studies. Its purpose is to make sure that he does a certain amount of carefully specified routine work. He can get a degree without undergoing any profound intellectual transformation; he can even get a degree without doing much work; but he cannot escape conformity to a prescribed academic routine. He must faithfully attend classes, hand in themes and exercises, undergo frequent tests and quizzes, follow instructions, and obey regulations, which are the same for all. He is treated not as an individual, but as a member of a group. . . .

Our college activities are organized on a different theory. Whereas in studies the virtue most in demand is docility, in extra-curricular clubs, teams, and societies the undergraduate has a chance to plan for himself, to exercise his own initiative, to succeed or fail on his own responsibility. It is not surprising that many students feel that they get the best part of their education outside the classroom and that employers often look more keenly at the young graduate’s record in activities than they do at his grades. Docility has its uses but independence and initiative are virtues of a higher order.39 The man who will do what he is told at the time he is told to do it has a certain value in the world, but the man who will do it without being told is worth much more. Consequently when one faces the problem of providing a more severe course of instruction for our abler students, one sees immediately that it is not sufficient merely to provide more of the same kind of work. The work must be different; it must not only be harder but must also offer more freedom and responsibility, more scope for the development of intellectual independence and initiative. . . .

The free elective system and the profusion of courses offered give each individual an embarrassing range of choice as to what he shall study. But the amount and difficulty of the work required in each course are rigidly standardized to the capacity of the average. It is not feasible to fail more than a small proportion of the members of each class, and this fact effectively limits the difficulty of the work required to what all or nearly all can do. The assignments or reading must not exceed in character or amount the capacity and interests of the student of average ability. The lectures and class discussions must not be over his head. The result is that the student of unusual ability suffers in many ways: he may become an idler, or he may devote his spare time to a wide variety of extra-curricular activities on which he tends to set an entirely fictitious value. In too many cases, comparing himself with his duller colleagues, he tends to rate too highly his own ability and achievements.

The student who is below the average standard, on the other hand, becomes discouraged and disheartened in the vain attempt to perform tasks which are too much for him. For a longer or shorter time he drags along, looking eagerly for easy courses, seeking help from private tutors, trying to catch up by attending summer schools, endeavoring by expedients which are sometimes pathetic and sometimes heroic to gain the coveted A.B. degree. A few succeed, but many are forced to confess themselves failures and to drop out, which is partly the reason why in many universities not more than one-fourth of the entering freshmen are able to graduate with their class. If one thinks in terms of education and not merely of the degree, it is obvious that the solution for both groups is to set them tasks adjusted to their mental capacity, their previous preparation, and their intellectual interests. . . .

Fifty years ago the limitations set by custom and interest upon entrance to college produced a student group of much more homogeneous character. Now our undergraduates are a cross section of the nation. It was, only when the number of college students increased so remarkably at the end of the last war that the menace to standards began to be widely recognized. By that time we were faced not merely with the difficulty of the average versus the superior student, but also with, a large and increasing group for whom even the average standard was too high.40

In the state universities, to which any high school graduate must be admitted on the basis of his diploma, and in many small colleges where need for students prevents the enforcement of any higher qualification for entrance, the standards of the average are beginning to be pulled down by the students who are below the average in ability or preparation. The number of these below-average students (roughly speaking those who graduate in the lower half of their class in high school) is constantly on the increase. These students are frequently not adapted to the subjects included in the ordinary program of study and they cannot keep up with the level of achievement of the average college student, modest as is that standard. They deserve nevertheless that their needs should be understood and met. It is important that the subjects they study be suited to their interests and that they should not learn to think of themselves as failures simply because they are set to perform tasks in which they are not interested and to which they are not equal. It is still more important that, just as the average student should not be allowed to pull down the level of the best, so these below-average individuals should not be allowed to become a threat to the standards of work of the average. Taken all in all, the variation in levels of ability of our undergraduates is the most serious problem confronting American higher education today. . . .41

The most serious of these hindrances is the confusion of thought inherent in our theories of democracy. To many people democracy means equality, and equality means uniformity. Our people wear the same clothes, eat the same food, drive the same cars, see the same movies, listen to the same radio programs. Why should they not have the same education? The fact that we do not all do the same kind of work, read the same books, look at the same paintings, or listen to the same music is for the moment forgotten. It is also forgotten that one of the purposes of democracy is to provide each individual with the opportunity that is best for him and that our society needs services of increasing variety and complexity. The end of democracy should be not to make men uniform, but rather to give them freedom to be individuals.

The confusion in the aims of democracy between uniformity and individualism comes home with special force to education: and it may well be that our colleges and universities, in solving the problem of the best treatment for students of different levels of ability, will contribute something to the solution of one of the central problems of the democratic way of life. We must guard against the temptation to think that a man’s worth as an individual or his value to society can be measured by his aptitude for mathematics or languages. We must recognize that there are diversities of gifts, but whether it be plumbing or Plato that is in question, a society that is not to be condemned to mediocrity must demand the best of each. . . .

From the beginning, as I have said, we . . . planned each honors course in co-operation between two or three related departments so as to give the student a program which would be clearly organized and focused upon a particular field, but not so narrowly specialized as would be the case were his work confined to a single department.

We soon decided upon the seminar method of teaching as opposed to individual tutorials. From the start we decided that for honors students the course and hour system should be abolished, that attendance at lectures and classes should be entirely voluntary, and that the honors degree should depend upon the student’s success in a series of examinations, written and oral, conducted by external examiners. Our most important and most difficult task was to decide upon the content of these examinations.

The question as to what the student should be expected to know in order to qualify for a degree was a novel one, and the members of the faculty had no answers ready. . . . At the end of six months or so of constant work by various committees only two honors courses were sufficiently agreed upon to make it possible for students to begin the next year—English literature and the social sciences.42 Accordingly, volunteers were called for in those two fields. . . .

The work, which was planned for two years, we subdivided into four parts for the four semesters, and the part for each semester into weeks, thus making a kind of program of reading and discussion for each seminar. The topic for a single meeting was usually split up into four or five subtopics corresponding to the number of students, and each undergraduate prepared a paper on one of these questions. In addition, all the students concerned were held responsible for a common background of reading which would enable them to discuss intelligently each other’s papers. For the first few years it was our practice to have two members of the faculty attend each seminar. Often there were more. . . .

Twenty years of honors work at Swarthmore have produced extraordinary changes in the atmosphere of the college. Of all the changes produced the most intangible and most important is the improvement in morale of students and members of the faculty alike. This seems to me fully as important from the point of view of building character as for its intellectual value. The best index of character is the sincerity and honesty and faithfulness with which an individual does his work. If an educational institution can be induced to put first things first, to subordinate everything else to its main business of education and scholarship, it will be sincere in a way that it cannot be if its principal pride is in its athletic teams or in some other irrelevant activity. That sincerity will make it a better place in which young people can live and grow. . . .

Something of the same kind has happened in the case of social activities. The complaint that in American academic life the side-shows seem to the students more important than the main performance may be due to the fact that the main performance has too often not been sufficiently difficult and adventurous to demand the best effort from the best. When that is corrected, when the academic program demands the utmost effort of the ablest students, all the other activities of college life fall into their rightful place. No negative regulation is necessary. Point systems and other devices for limiting the participation of students in extra-curricular activities are no longer needed. The best students, who set the pace and start the fashions, will make the right choices, and the atmosphere of the college will change from that of a country club to that of an educational institution.43

Willis Rudy (1920–2004) was born and raised in New York City, where he graduated with a B.S. from the City College of New York in 1939. He then taught at his alma mater until completing his Ph.D. at Columbia University in 1948. After teaching as an instructor at Harvard University, Rudy joined the faculty of the state teachers college in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1953 and co-authored with John S. Brubacher what became a standard history of American higher education: Higher Education in Transition: An American History, 1636–1956. In 1956 the Carnegie Corporation of New York invited Rudy to undertake a national study of college catalogs in order to determine the formal changes that had occurred in the liberal arts curriculum during the first half of the twentieth century. Rudy’s research was part of a large project, located at Teachers College, Columbia University, examining undergraduate professional education, which had grown from ancillary parallel courses in the nineteenth century into the predominant component of the undergraduate curriculum by the 1950s. In 1960 Rudy’s study was published, and in 1963 he became a professor of history at Farleigh Dickinson University, where he remained for the rest of his career.

In selection #61, Rudy sketches what he considered to be the “emerging curricular blueprint” for the liberal arts, which incorporated a growing number of departments and courses at nearly all colleges and universities. This “vast expansion and diversification of liberal arts college course offerings” eventually contributed to the “looseness” in academic regulation observed by Gerald Grant and David Riesman in selection #64.

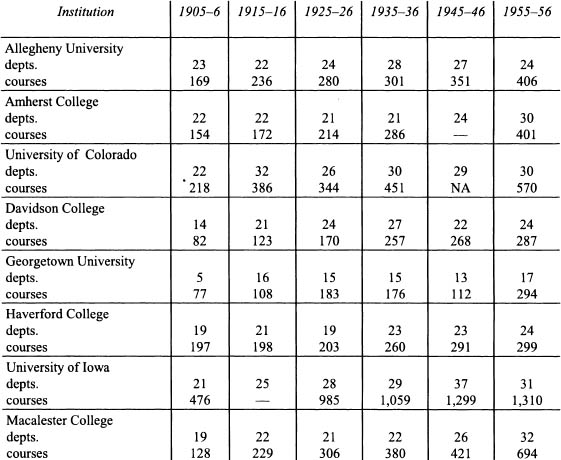

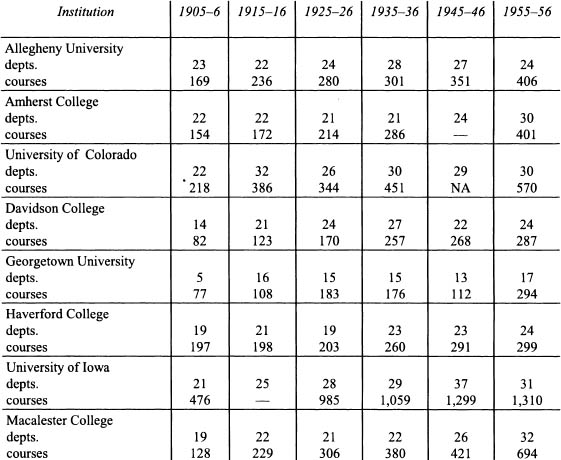

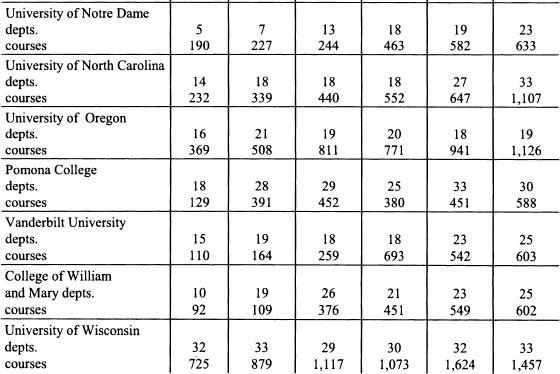

In order to carry forward a detailed study of college curricula into the twentieth century, institutions were selected and their catalogs were examined at ten-year intervals, beginning in 1905 and proceeding through the year 1955. . . . The exact proportions and extent of change in terms of two measurable items—namely, the number of separate, functioning departments of instruction and the number of semester courses offered—can be determined through a study of the college catalogs. The data thus collected reveal notable increases in both categories during the period from 1905 to 1955.

What generalizations can we draw from these data? One obvious trend is the vast expansion and diversification of liberal arts college course offerings. In response to the demands of an increasingly complex social order, vocations such as business and finance, journalism, public health, music, architecture, the theater, and fine arts were gaining entrance to the college curriculum as fields with distinct intellectual content. Charles W. Eliot of Harvard observed in 1917 that these undertakings had “become to a much greater extent than formerly an intellectual calling, demanding good powers of observation, concentration, and judgment.” Eliot, leader in the campaign for a completely free elective system, remarked that it was no longer the principal business of the colleges to train scholarly young men for the service of church, state, and bar. Now they were increasingly called upon “to train young men for public service in new democracies, for a new medical profession, and for finance, journalism, transportation, manufacturing, the new architecture, the building of vessels and railroads, and the direction of great public works which improve agriculture, conserve the national resources, provide pure water supplies, and distribute light, heat, and mechanical power.”45

As specialization advanced, the areas of elective study in the college curriculum expanded with equal rapidity. . . . The emerging curricular blueprint devoted the first two years of the undergraduate course to general education in fundamental liberal arts subjects and the last two to more specialized, often frankly professional, training. Upper-division specialization of this kind fostered a growing departmentalization of the college curriculum. An analysis of the college catalogs reveals the sweeping nature of this trend between 1905 and 1955, as seen in the table of representative institutions on the following page.

Many college presidents, as, for example, William Rainey Harper of the University of Chicago, saw academic specialization as valuable in its own right. Specialization was encouraged by rewarding productive specialists on the faculty with promotions and by seeking only specialists for staff vacancies. It was recognized more and more by academic careerists that in order to make one’s mark professionally and advance in one’s calling, it was necessary to specialize.46

Table: Departments and Courses in Selected Colleges and Universities, 1905–1956

Reflecting this new emphasis, college faculties were reorganized on the basis of specialized departmental areas of scholarly and professional interest.47 Closely paralleling this increasingly atomistic faculty organization was a compartmentalization of the curriculum in terms of carefully demarcated areas of college instruction. In 1931 President William L. Bryan of the University of Indiana described the situation as one which “tempts every department in the college to become primarily a breeding place for specialists, each department after its kind.” . . . This, Bryan believed, had completely transformed the nature of the American liberal arts college.48

The number of such specialized departments in the average college was increased also by the demands of newer fields of study for recognition. Fields such as experimental psychology, sociology, anthropology, modern literature, speech and drama, and various subdivisions and specialties in the natural sciences were pushing their way forward and laying claim to a place in the sun.

While professional specialization was thus becoming the watchword of the liberal arts college from one end of the nation to the other, there was considerable variation in the way this approach was actually implemented. Perhaps the most popular solution of the problem was some form of the “major-minor” system. In accordance with this pattern, all undergraduates followed a prescribed program of general studies during their first two years in college and then majored or concentrated in some one subject-matter area during the last two. At the same time, they were expected to select one or two minor subjects and distribute most of their remaining upper-division credits among these fields. A variant of the major plan was the “area study” type of concentration, under which a student specialized on an interdepartmental basis in the civilization of one of the main regions of the world, such as Latin America or the Near East.

In the years following the first world war undergraduate specialization was also advanced by the introduction of systems of independent study and honors work in the junior and senior years of many liberal arts colleges.49 Increasingly, it became clear that whatever else their purpose, such honors courses on the undergraduate level made possible the early training of persons who were pointing toward Ph.D.s and careers as research specialists or college professors. Departmental statements in the annual catalogs of many institutions made no attempt to conceal this objective. They frankly admitted that undergraduate specialization by means of individual honors or independent study programs would serve as a valuable preliminary to later professional specialization in graduate school.50

What were some of the other means by which professional specialization was entering into the college curriculum? In nearly every institution we have selected for study an established feature came to be the offering of special pre-professional course sequences preparing directly for admission to schools of medicine, law, theology, dentistry, medical technology, engineering, nursing, social welfare, and public service. Invariably, the bulk of this special pre-professional work came in the third and fourth undergraduate years. Closely related to this type of program was the so-called “combined course” under which students dovetailed the semi-professional work of their senior year in college with the equivalent of the first year’s work of a professional school.

This system, most often found in liberal arts colleges which were affiliated with large, multi-unit universities, made it possible for students to shorten by at least one year the time of their combined academic and professional training, while securing both a bachelor’s degree and a professional degree. Combined courses were offered most frequently in fields such as law, medicine, and engineering. In these callings, the system had made its appearance even before the advent of the twentieth century.

Still another feature in many liberal arts colleges was the partial or terminal programs of a frankly professional nature which were made available to students during their junior and senior years. These offerings ranged over fields as varied as journalism, public health, physical education, geology, library science, petroleum engineering, applied and manual arts, forestry, social work, business administration, chemical engineering, and radio, drama, and the dance. And nowhere did the colleges under review more universally recognize a professional aim than in their programs preparing teachers for the secondary schools. Nearly all had education departments which offered specific sequences of professional courses in education in order to equip their students to teach and to meet state certification requirements.

As more and more professional programs were introduced in the liberal arts colleges, many new kinds of academic degrees were established and the traditional baccalaureate came to acquire new meanings. Richardson’s study of private liberal arts colleges during the period 1890 to 1940 resulted in findings very similar to our own. Among the 105 institutions included in his survey, many new types of bachelor’s degrees were discovered to be splitting off from the original B.A. and B.S. . . .51