Chapter 4

Ionophores in Planar Lipid Bilayers

Chapter Outline

I Summary

Planar lipid bilayers made from synthetic lipids and incorporating ionophores such as valinomycin or gramicidin, provide a useful tool for the study of membrane transport. Fusion of vesicles from native cell membranes into planar lipid bilayers provides information concerning ion channels that complements what is available from patch-clamp studies. Selective ion channels in planar lipid bilayers display high transport rates and low temperature coefficients, characteristics that distinguish ion channels from other modes of mediated transport. Finally, the features of cation transport by gramicidin in planar lipid bilayers are summarized. Detailed kinetic studies have shown that transport of cations and water through gramicidin occurs by means of single-file diffusion in which the ions and the waters cannot pass each other in the narrow part of the pore. The cation binds at a site near either end of the pore and then is driven over an energy barrier in the pore by the electrochemical gradient. The rate-limiting step, however, is the dissociation of the ion from the channel.

II Ionophores

Ionophores are a class of compounds that form complexes with specific ions and facilitate their transport across cell membranes. An ionophore typically has a hydrophilic pocket (or hole) that forms a binding site specific for a particular ion. The exterior surface of an ionophore is hydrophobic, allowing the complexed ion in its pocket to cross the hydrophobic membrane. A list of ionophores showing the ion specificity of each is given in Table 4.1. Ionophores are useful tools in cell physiology experiments. Nystatin forms a channel in membranes for monovalent cations and anions and has proven useful for altering the cation composition of cells. Gramicidin forms dimeric channels specific to monovalent cations. Valinomycin carries K+ across membranes with a high selectivity and has been used extensively to impose a high K+ permeability on cell membranes. Monensin is a carrier with specificity for Na+. Hemisodium is a synthetic Na+ ionophore with an even greater degree of selectivity for Na+. The Ca2+ ionophore A23187 has been used extensively to permit entry of Ca2+ into cells, which normally have a low native permeability to Ca2+, and thereby to activate a variety of cellular processes that are regulated by Ca2+. Nigericin exchanges K+ for protons and has been used in many studies of mitochondrial bioenergetics to alter electrical and chemical gradients for protons. Ionophores such as FCCP and CCCP are specific for protons. Study of the mechanism of membrane transport mediated by ionophores has provided important conceptual insights relevant to the understanding of ion transport mediated by native transport proteins.

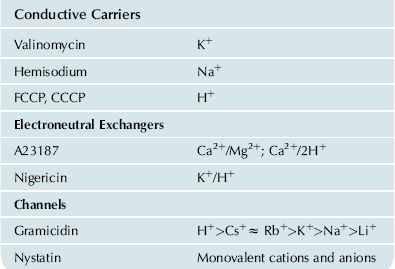

TABLE 4.1. Ionophores and their Ion Selectivities

III Planar Lipid Bilayers

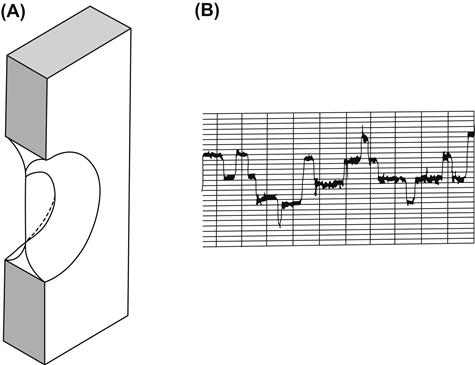

Planar lipid bilayers, also called black lipid membranes (BLMs), were first described in 1963 by Mueller and colleagues using the painting technique. A small aperture of about 1 mm diameter in a Teflon or polyethylene septum separating two aqueous salt solutions is coated by means of a beveled Teflon rod with a solution of pure lipids that are usually dissolved in decane. The thick lipid film covering the aperture then spontaneously thins to a bimolecular lipid leaflet surrounded by a thicker annular torus (Fig. 4.1A). The bimolecular portion of the film appears black because light reflected from the front surface undergoes a phase shift of 180° and destructively interferes with light reflected from the back surface. The film thickness of about 100 Å is small compared to the wavelength of visible light (3800–7600 Å). The lipids used to make the film are usually commercially purchased phospholipids – phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylserine (PS), cardiolipin – and are sometimes supplemented with cholesterol for added stability. The proportions of the various lipids in the bilayer are set by dissolving the pure lipids in chloroform/methanol, mixing in desired proportions, evaporating the solvent with a stream of nitrogen and then re-dissolving the mixed lipids in decane.

FIGURE 4.1 (A) Septum with planar lipid bilayer. (B) Traces showing currents through four dimeric gramicidin channels associating and dissociating in a black lipid membrane, as determined in the author’s laboratory.

The first attempts at reconstituting native ion channels into planar lipid bilayers were made by adding cell membrane extracts or partially purified membrane proteins into the aqueous solutions. Increases in electrical conductance were noted, often followed by breakage of the membrane; these effects were often due to adsorption of protein onto the bilayer and a generalized non-specific disruption of the membrane associated with increased leakage of current. Some success was achieved by adding membranes, membrane proteins or membrane extracts directly to the lipid-forming solution. Subsequently, techniques were developed for fusing vesicles, either native vesicles isolated from cell membranes or, alternatively, vesicles reconstituted with specific ion channels, into the planar lipid bilayer (see Miller, 1986, 1987). Tip-dipping is an alternative technique involving dipping the tip of a micropipette into a pure lipid film twice to form a bilayer covering the tip of the pipette so as to form a tight electrical seal, with a resistance of 1–5 GΩ (1 GΩ = 1015 Ω). Tip-dipping improves the time resolution and reduces noise due to the smaller area of membrane that is being examined; this technique allows the study of asymmetric bilayers and does not require solvents if the monolayers are formed from dried lipids (Coronado and Latorre, 1983).

The planar lipid bilayer technique is an excellent method for studying the transport kinetics of lipid-soluble ionophores. With planar lipid bilayers, one can easily vary the membrane lipid composition and also change the solutions or add reagents on either side of the membrane. Purified membrane channels may be studied apart from the regulatory mechanisms of intact cells and the resultant information should complement that obtained from patch-clamp studies of intact cells. Planar lipid bilayers can also be used as an assay for channel purification. The planar lipid bilayer technique has several disadvantages. One is that the membranes tend to break. Once observed, the channels may disappear during the period of observation by diffusing into the thick annulus around the bilayer. The organic solvent, when present, may alter the properties of ion channels. The increases in conductance that are detected may not necessarily be physiologically relevant because the conductance properties may change during isolation of the vesicles or during purification of the channels and the conductances themselves may originate from small amounts of impurities or from contaminating cells. Some channels incorporate into bilayers more easily than others, so there may be long periods of time when nothing happens and the channel ultimately studied may not be the channel that was desired to be studied.

IV Ion Channel Properties in Planar Lipid Bilayers

Studies of ion transport through channels in planar lipid bilayers revealed that ion channels are characterized by high transport rates and low temperature coefficients. Observations of single ion channels show that the current passing through a channel is on the order of picoamps (10−12 A). In order to convert 1 pA to the flux J in ions/s, note that the flux through a channel can be estimated from the single channel current i (C/s), using Avogadro’s number NA (ions/mol), the Faraday constant F (C/eq) and the ionic valence z (eq/mole).

So for 1 pA of current carried by a univalent ion, we have:

or 6 million ions/s. By comparison, enzymes and membrane transporters that are not ion channels have turnover rates that are less than 105/s. For example, the Na+,K+-ATPase pumps at a maximal rate of about 100 ions/s. The fastest non-channel transporter is the Cl−-HCO3− exchanger of red blood cells, which has an exchange rate of 104 ions/s at 25°C. The enzymes carbonic anhydrase and acetylcholinesterase have turnover rates of about 105/s. Thus, ion channels typically show high transport rates, one to several orders of magnitude faster than the fastest enzymes or non-channel transporters.

Ion channels were also found to have low temperature coefficients. Q10 is defined to be the change in the rate of a reaction when the temperature is increased by 10°C. Hodgkin and Huxley found that Q10 for Na+ and K+ currents in squid axon is 1.2–1.4, which is comparable to that for unrestricted diffusion of ions in free solution, a finding consistent with these ions moving through ion channels in nerve membranes. From thermodynamics, the Q10 is related to the enthalpy of activation for the reaction. The Q10 for Na+ and K+ currents in squid axon corresponds to an enthalpy of activation of only 5 kcal/mol. Enzymes and non-channel transporters have a Q10 of 3–4 or higher, corresponding to higher enthalpies of activation.

V Gramicidin

One of the best-studied ion channels in planar lipid bilayers is gramicidin, an antibiotic synthesized by Bacillus brevis against Gram-positive bacteria (hence the name). Gramicidin is commercially used as a topical bacteriostatic agent. The primary sequence of gramicidin A is a linear pentadecapeptide consisting of 15 alternating D- and L-amino acids. Natural sequence variations occur at position 11 with substitution of Trp with Phe (gramicidin B) or Tyr (gramicidin C). The natural mixture is termed gramicidin D and contains about 80% gramicidin A. All of the amino acids in gramicidin are hydrophobic with no free charges. Gramicidin is thus virtually insoluble in water. Both end groups are blocked: the N-terminal valine (the head) is blocked by a formyl group; the C-terminal tryptophan (the tail) is blocked by an ethanolamine. In membranes, the peptide chain is wound in a β-helix with a pore right down the central core of the molecule (Fig. 4.2). Carbonyl and imino groups of the peptide bonds line the pore. All amino acid side chains extend away from the pore into the membrane lipid. The β-helix is stabilized by –NH ··· O– hydrogen bonds extending parallel to the pore axis. The aqueous pore is about 25 Å long and 4 Å in diameter. Gramicidin assumes different conformations in organic solvents; the double helical structure deduced from spectroscopic studies does not pertain to the channel conformation in membranes. The conducting pore is formed by a head-to-head dimer linked transiently by six hydrogen bonds. Evidence for a head-to-head dimer is that chemical modifications at the N-terminus (the head) drastically affect channel formation, whereas similar modifications at the C-terminus (the tail) do not. With fluorescent analogs of gramicidin, it was possible to measure simultaneously the conductance and the concentration of gramicidin in the membrane. The conductance was proportional to the square of the gramicidin concentration, and the equilibrium constant for dimerization was determined (Veatch et al., 1975). Since gramicidin is synthesized non-ribosomally in vivo and contains D-amino acids that are not normally genetically coded, site-directed mutagenesis using recombinant DNA methods is not possible. Chemical synthesis has permitted alterations of the primary sequence for studies relating chemical structure to ion transport function.

FIGURE 4.2 Space-filling model of gramicidin. (From Urry, D.W. (1972) A molecular theory of ion-conducting channels: a field-dependent transition between conducting and nonconducting conformations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 69, 1610-1614, with permission.)

Hladky and Haydon (1972) first observed single-channel conductances with gramicidin in planar lipid bilayers (see Fig. 4.1B for an example). The channel lifetimes are on the order of a second (compared to ms for Na+ channels). With symmetrical 0.1 M NaCl, the single-channel current is 1.0 pA at 200 mV, corresponding to a single-channel conductance of 5 pS and a flux of 6.3×106 ions/s. The high flux is consistent with a channel mechanism. The highest conductance so far reported is 107 pS at 23°C with 3 M RbCl solutions in a neutral membrane made from glycerylmonooleate-hexadecane mixtures. The mean single-channel lifetime depends on lipid dynamics. For example, channels in thicker membranes, where pinching of the membrane may be required for dimer formation, have shorter lifetimes. Greater interfacial tension shortens channel lifetime.

Despite the absence of fixed negative charges in the pore, the gramicidin channels are cation selective (Myers and Haydon, 1972). The permeability ratios are determined from bi-ionic potentials, whereas the conductance ratios are determined in symmetrical salt solutions. The channels are ideally selective to cations. With a gradient of monovalent chloride salt, the reversal potential equals the Nernst potential for the cation, implying that the permeability to Cl− is negligible. The channel is also impermeant to divalent cations. The selectivity order corresponds to Eisenman’s sequence I, indicative of a weak field strength interaction between the pore and the ions.

The selectivity for K+:Na+ is only about 4:1 – much less than that of the delayed rectifier K+ channel (20:1 to 100:1), which is primarily responsible for resetting the resting potential of nerve and muscle following activation, and very much less than that of the carrier valinomycin (more than 1000:1).

The gramicidin channel is blocked by divalent cations (e.g. Ca2+, Ba2+ and, to a lesser extent, Mg2+ and Zn2+). These ions probably block by binding near the channel mouth and occluding entrance into the channel. Flicker block may be observed with iminium ions; this transient block is thought to result from transient association of these ions with the channel wall during permeation.

Passage of ions or water through gramicidin is by means of single-file transport. The high proton conductance, and the known geometrical dimensions of the pore, suggest that the pore is filled with a continuous column of hydrogen-bonded water molecules (2.8 Å). The diffusive water permeability through gramicidin in bilayers has been measured with tracers and is about 108 water molecules per second at low ionic strength. Water permeation is probably by means of a Grotthus, or “hopping” mechanism (see Chapter 1). The pore diameter is too small to permit passage of urea (5 Å diameter) or larger non-electrolytes. Consequently, a streaming potential develops when non-electrolyte is added to the salt solution on one side of the bilayer to make an osmotic gradient. In another type of study, an electro-osmotic volume flow occurs when an ionic current is passed across the membrane. For single file transport, the number N of water molecules in the channel is obtained by dividing the water flux ϕw (molecules/s) by the ion flux J (ions/s):

For gramicidin channels, the number N of water molecules in the pore is 5–6. Quantitative analysis of streaming potentials and electro-osmosis indicates that an ion passing through a gramicidin channel drags with it a column of about six water molecules in single file.

The channel is too narrow for water molecules to slip past each other; nor can ions and water molecules pass each other in the single-file part of the channel. However, sodium ion occupancy does not depress water permeability. The water permeability of a channel at high [Na+], when the channel always contains a sodium ion, is essentially the same as that of a channel at low [Na+], when the channel never contains a sodium ion. Thus, water can pass the sodium ion somewhere in the channel, presumably near an ion-binding site at the end of the channel.

The single-channel conductance for sodium increases as a function of Na+ concentration, but then saturates at around 1 M NaCl. Half-maximal conductance is reached at 0.31 M NaCl, at which concentration half the channels have one Na+ ion and half are empty. The curve of conductance g versus [Na+] fits a single-ion occupancy model, given by:

where C1/2 is the concentration of Na+ that gives half-maximal conductance. The single-ion occupancy model indicates that an ion-binding site, or energy well, exists near the end of the channel. Since the dimeric structure is symmetrical, there must be two binding sites, one at each end, but only one at a time is occupied by sodium. Additional compelling evidence for single-ion occupancy for sodium is that the flux ratio equation is satisfied at all sodium concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 5 M. Given that single-file transport occurs, a net flux in one direction would inhibit the unidirectional flux in the opposite direction, thus producing deviations from the flux ratio equation if the two Na+ binding sites were simultaneously occupied. Consequently, double occupancy must not occur for Na+. These two lines of evidence imply that there is never more than one sodium ion at a time in the gramicidin channel (Sandblom et al., 1977).

The dehydration energy for ions is of the order of 100 kcal/mol; the selectivity sequence indicating a weak field strength interaction with the pore suggests that ions do not dehydrate during passage through the gramicidin pore. The hydration shell of water around the permeating ions is partially replaced by hydrophilic groups lining the channel wall. The dielectric constant is lower in the middle of the pore than near the ends of the pore. Thus, the electrostatic energy of the ion in the middle of the pore is greater than at either end of the pore. The actual flux of Na+ at high [Na+] is within a factor of 5 of the maximal possible flux of Na+, given the water permeability of an ion-free channel. This means that there is no significant electrostatic energy barrier to Na+ movement through the channel. The rate of Na+ transport is largely determined by the necessity for six water molecules to be moved along with the ion. Thus, two energy wells near the ends of the channel are separated by a low-energy barrier (or a series of small barriers) in the middle of the channel. Strict single filing of water and ions occurs between the two wells, whereas water can pass a sodium ion sitting in either well. The kinetic equations describing single-file transport are complex and beyond the scope of this text (see Finkelstein and Anderson, 1981).

Cation transport through gramicidin also involves channel motions, subconductance states and channel flickering. The gramicidin channel is not rigid but, instead, motion of the peptide appears to be essential to its function. Solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) measurements of 15N-labeled Ala 3 and Leu 4 indicate rocking motions of ±8° and ±15°, respectively, for these sites in the absence of ions. Molecular dynamics simulations confirm local distortions in gramicidin structure during ion transport. Peptide rotation is not necessary for function since the channel is active in gel-phase lipid. Subconductance states, or “mini-channels”, are frequently observed as an intermediate in the opening and closing of normal channels. These may constitute from 5 to 40% of the channel events in a single-channel recording, with lifetimes similar to those of normal gramicidin channels. The low-conductance state may correspond to less common side-chain conformations with altered coordinating ability in the conducting pore. Channel flickering to a low-conductance state with lifetimes ranging from 20 μs to about 1 ms is also observed. Rapid flickering may correspond to a state in which the dimer is partially dissociated. An increase in membrane thickness increases the frequency of these low-conductance states. This rather detailed analysis of ion channel permeation through gramicidin channels in planar lipid bilayers provides some basis for understanding ion permeation through native ion channel proteins in cell membranes.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Coronado R, Latorre R. Phospholipid bilayers made from monolayers on patch-clamp pipettes. Biophys J. 1983;43:231–236.

2. Ehrlich B. Planar lipid bilayers on patch pipettes: bilayer formation and ion channel incorporation. Meth Enzymol. 1992;207:463–470.

3. Finkelstein A. Bilayers: formation, measurements, and incorporation of components. Meth Enzymol. 1974;32B:489–501.

4. Finkelstein A, Andersen OS. The gramicidin A channel: a review of its permeability characteristics with special reference to the single-file aspect of transport. J Memb Biol. 1981;59:155–171.

5. Hille B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. 3rd ed. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates Inc.; 2001.

6. Hladky SB, Haydon DA. Ion transfer across lipid membranes in the presence of gramicidin A I Studies of the unit conductance channel. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972;274:294–312.

7. Labarca P, Latorre R. Insertion of ion channels into planar lipid bilayers by vesicle fusion. Meth Enzymol. 1992;207:447–463.

8. Miller C. Ion Channel Reconstitution. New York: Plenum Press; 1986.

9. Miller C. How ion channel proteins work. In: Kaczmarek LK, Levitan IB, eds. Neuromodulation The Biochemical Control of Neuronal Excitability. New York: Oxford University Press; 1987;:39–63.

10. Montal M, Mueller P. Formation of bimolecular membranes from lipid monolayers and a study of their electrical properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:3561–3566.

11. Mueller P, Rudin DO, Ti Tien H, Wescott WC. Methods for the formation of single bimolecular lipid membranes in aqueous solution. J Phys Chem. 1963;67:534–535.

12. Myers VB, Haydon DA. Ion transfer across lipid membranes in the presence of gramicidin A II The ion selectivity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972;274:313–322.

13. Sandblom J, Eisenman G, Neher E. Ionic selectivity, saturation and block in gramicidin A channels: I Theory for the electrical properties of ion selective channels having two pairs of binding sites and multiple conductance states. J Memb Biol. 1977;31:383–417.

14. Veatch WR, Mathies R, Eisenberg M, Stryer L. Simultaneous fluorescence and conductance studies of planar bilayer membranes containing a highly active and fluorescent analog of Gramicidin A. J Mol Biol. 1975;99:75–92.

15. Woodbury DJ, Hall JE. Role of channels in the fusion of vesicles with a planar bilayer. Biophys J. 1988;54:1053–1063.

16. Woodbury DJ, Miller C. Nystatin-induced liposome fusion A versatile approach to ion channel reconstitution into planar bilayers. Biophys J. 1990;58:833–839.

17. Wooley GA, Wallace BA. Model ion channels: gramicidin and alamethicin. J Memb Biol. 1992;129:109–136.