Chapter 9

Origin of Resting Membrane Potentials

Chapter Outline

III. Passive Electrical Properties

IV. Maintenance of Ion Distributions

IVA. Resting Potentials and Ion Distributions

IVB. Na+ and K+ Distribution and the Na+-K+ Pump

IVD2. Cai - Nao Exchange Reaction

VI. Electrochemical Driving Forces and Membrane Ionic Currents

VII. Determination of Resting Potential and Net Diffusion Potential (Ediff)

VIII. Electrogenic Sodium Pump Potentials

AI. More Details on Ca2+-Na+ Exchanger

AII. Derivation of Nernst Equation

AIV. Constant-Field Equation Details

AV. Derivation of Chord Conductance Equation

I Summary

Most of the factors that determine or influence the resting Em of cells are discussed in this chapter. The structural and chemical composition of the cell membrane is briefly examined and correlated with the resistive and capacitative properties of the membrane. The factors that determine the intracellular ion concentrations in cells are examined. These factors include the Na+-K+-coupled pump, the Ca2+-Na+ exchange reaction and the sarcolemmal Ca2+ pump. The Na+-K+ pump enzyme, Na+,K+-ATPase, requires both Na+ and K+ for activity and transports three Na+ ions outward and usually two K+ ions inward per ATP hydrolyzed. Cardiac glycosides are specific blockers of this transport ATPase. The Na+-K+ pump, if electroneutral, is not directly related to excitability, but only indirectly related by its role in maintaining the Na+ and K+ concentration gradients.

The carrier-mediated Ca2+-Na+ exchange reaction is driven by the Na+ electrochemical gradient; i.e. the energy for transporting out internal Ca2+ by this mechanism comes from the Na+,K+-ATPase. The Ca2+-Na+ exchange reaction exchanges one internal Ca2+ ion for three external Na+ ions when working in the forward mode in cells at rest. In myocardial cells, during the action potential (AP) plateau depolarization, the energetics cause the Ca2+-Na+ exchanger to operate in reverse mode, allowing Ca2+ influx.

The mechanism whereby the ionic distributions give rise to diffusion potentials is discussed, as are the factors that determine the magnitude and polarity of each ionic equilibrium potential. The equilibrium potential for any ion and the transmembrane potential determine the total electrochemical driving force for that ion and the product of this driving force and membrane conductance for that ion determines the net ionic current. The direction of the net ionic movement, inward or outward, depends on the direction of the electrochemical gradient.

The key factor that determines the resting Em is the relative permeability of the various ions, particularly of K+ and Na+, i.e. the PNa/PK ratio (or gNa /gK ratio), as calculated from the constant-field equation. The major physiologic ions that have some effect on the resting Em or on the APs are K+, Na+, Ca2+ and Cl−. The Ca2+ electrochemical gradient has only a small direct effect on the resting Em, although low external Ca2+ can affect the permeabilities and conductances for the other ions, such as Na+ and K+. Elevation of internal Ca2+ can increase the permeability to K+ by activating Ca2+-operated K+-selective IK(Ca) channels.

Cl− is usually passively distributed according to the membrane potential, i.e. not actively transported. However, there is some evidence indicating that, in some smooth muscle cells, [Cl−]i. may be about twice as high as that predicted from Em. If so, this would give an ECl value about 18 mV less negative than the resting Em. Before one can conclude that there is a Cl− pump directed inward, however, the calculated ECl must be significantly more positive than the mean resting Em averaged over time; i.e. any spontaneous APs must be taken into account. If Cl− is passively distributed, it cannot determine the resting Em. However, transient net movements of Cl− ions, e.g. during the AP, do affect the Em, particularly when gCl is high.

Elevation of [K+]o to more than the normal concentration of about 4.5 mM decreases the K+ equilibrium potential (EK), as predicted from the Nernst equation ([K+]i. constant) and depolarization is produced.

Not only is the resting Em the potential energy storehouse that is drawn upon for production and propagation of the APs but, because the membrane voltage-dependent cationic channels are inactivated with sustained depolarization, the rate of rise of the AP, and hence propagation velocity, is critically dependent on the level of the resting Em. For example, a relatively small elevation of K+ concentration in the blood has dire consequences for functioning of the heart.

The contribution of the Na+-K+ pump to the resting Em depends on: (1) the coupling ratio of Na+ pumped out to K+ pumped in; (2) the turnover rate of the pump; (3) the number of pumps; and (4) the magnitude of the membrane resistance. The electrogenic pump potential is in parallel to the net ionic diffusion potential (Ediff), determined by the ionic equilibrium potentials and relative permeabilities. The contribution of the electrogenic pump potential to the measured resting Em of cells varies from 2 to 16 mV, depending on the type of cell. The immediate depolarization produced by complete Na+-K+ pump stoppage with cardiac glycosides is only a few millivolts in cells like myocardial cells. Of course, long-term pump inhibition produces a larger and larger depolarization as the ionic gradients are dissipated. The rate of Na+-K+ pumping, and hence the magnitude of the electrogenic pump contribution to Em, is controlled primarily by [Na+]i and by [K+]o. The electrogenic pump potential might be physiologically important to various tissues, particularly the heart, under certain conditions that tend to depolarize the cells, such as transient ischemia or hypoxia. In such cases, the actual depolarization produced may be less because of a relatively constant pump potential in parallel with a diminishing Ediff. The electrogenic pump potential may also affect automaticity of the nodal cells of the heart, as well as other cells that exhibit automaticity.

II Introduction

The cell membrane exerts tight control over the electrical activity and the contractile machinery during the process of excitation–contraction (electromechanical) coupling. Some drugs and toxins exert primary or secondary effects on the electrical properties of the cell membrane and thereby exert effects, for example, on automaticity, arrhythmias and force of contraction of the heart. Therefore, for an understanding of the mode of action of therapeutic drugs, toxic agents, neurotransmitters, hormones and plasma electrolytes on the electrical activity of nerve and muscle, it is necessary to understand the electrical properties and behavior of the cell membrane at rest and during excitation. The first step in gaining such an understanding is to examine the electrical properties of nerve and muscle cells at rest, including the origin of the resting membrane potential (Em). The resting Em and action potential result from properties of the cell membrane and the ion distributions across it.

III Passive Electrical Properties

IIIA Membrane Structure and Composition

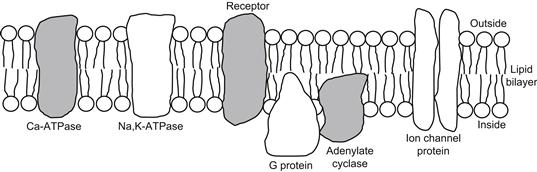

As discussed in previous chapters, the cell membrane is composed of a bimolecular leaflet of phospholipid molecules with protein molecules floating in the lipid bilayer. The non-polar hydrophobic ends of the phospholipid molecules project toward the middle of the membrane and the polar hydrophilic ends project toward the edges of the membrane bordering on the water phases (Fig. 9.1). This orientation is thermodynamically favorable. The lipid bilayer membrane is about 50–70 Å thick and the phospholipid molecules are about the right length (30–40 Å) to stretch across half of the membrane thickness. Cholesterol molecules are in high concentration in the cell membrane (of animal cells) and are inserted between the phospholipid molecules, giving a phospholipid/cholesterol ratio of about 1.0. Some of the large protein molecules, called integral membrane proteins, protrude through the entire membrane thickness; e.g. the Na+, K+-ATPase, Ca2+-ATPase and the various ion channel proteins (i.e., protrude through both leaflets), whereas other proteins are inserted into one leaflet (inner or outer) only. These proteins “float” in the lipid bilayer matrix and the membrane has fluidity (reciprocal of microviscosity), such that the protein molecules can move around laterally in the plane of the membrane. Some ion channels, e.g. fast Na+ channels of the node of Ranvier of myelinated neurons, are tethered in place to the cytoskeleton by anchoring proteins, such as ankyrin.

FIGURE 9.1 Diagrammatic illustration of cell membrane substructure showing the lipid bilayer. Non-polar hydrophobic tail ends of the phospholipid molecules project toward the middle of the membrane and polar hydrophilic heads border on the water phase at each side of the membrane. Lipid bilayer is about 50–70 Å thick. For simplicity, the cholesterol molecules are not shown. Large protein molecules protrude through entire membrane thickness or are inserted into one leaflet only, as depicted. These proteins include various enzymes associated with the cell membrane as well as membrane ionic channels. Membrane has fluidity so that the protein and lipid molecules can move around in the plane of the membrane.

The outer surface of the cell membrane is lined with strands of mucopolysaccharides (the cell coat or glycocalyx) that endow the cell with immunochemical properties. The cell coat is highly charged negatively and therefore can bind cations, such as Ca2+. Treatment with neuraminidase to remove sialic acid residues destroys the cell coat.

IIIB Membrane Capacitance and Resistivity

Lipid bilayer membranes made artificially have a specific membrane capacitance (Cm) of 0.4–1.0 μF/cm2, which is close to the value for biological membranes. The capacitance of biological cell membranes is due to this lipid bilayer matrix. A capacitor consists of two parallel plate conductors separated by a dielectric material of high resistance (e.g. oil). The factors that determine the value of the capacitance of a membrane are given in the equation:

(9.1)

(9.1)

where Am is the membrane area (in cm2) and k is a constant (9.0×1011 cm/F). Calculation of membrane thickness (δ) from Equation 9.1, assuming a measured membrane capacitance (Cm) of 0.7 μF/cm2 and a dieletric constant (ε) of 5, gives 63 Å. Most oils have dielectric constants of 3–5. The more dipolar the material, the greater the dielectric constant. For example, water, which is very dipolar, has a value of 81, compared with a value of 1.000 for a vacuum (air is nearly equal to that of vacuum).

The artificial lipid bilayer membrane, on the other hand, has an exceedingly high specific resistance (Rm) of 106–109 Ω⋅cm2, which is several orders of magnitude higher than that of the biological cell membrane (about 103 Ω⋅cm2). Rm is greatly lowered, however, when the bilayer is doped with certain proteins or substances, such as macrocyclic polypeptide antibiotics (ionophores). The added ionophores may be of the ion-carrier type, such as valinomycin, or of the channel-former type, such as gramicidin. Therefore, the presence of proteins that span across the thickness of the cell membrane must account for the relatively low resistance (high conductance) of the cell membrane. These proteins include those constituting the voltage-dependent gated ion channels of the cell membrane. In summary, the capacitance is due to the lipid bilayer matrix and the conductance is due to proteins inserted in the lipid bilayer.

The dielectric property of the cell membrane is very good. For a resting Em of −80 mV and a thickness of 60 Å, the voltage gradient sustained across the membrane is 133 000 V/cm. Thus, the cell membrane tolerates an enormous voltage gradient.

IIIC Membrane Fluidity

The electrical properties and the ion transport properties of the cell membrane are determined by the molecular composition of the membrane. The lipid bilayer matrix even influences the function of the membrane proteins; e.g. the Na+, K+-ATPase activity is affected by the surrounding lipid. A high cholesterol content lowers the fluidity of the membrane. The polar portion of cholesterol lodges in the hydrophilic part of the membrane and the non-polar part of the planar cholesterol molecule is wedged between the fatty acid tails, thus restricting their motion and lowering fluidity. A high degree of unsaturation and branching of the tails of the phospholipid molecules raises the fluidity; phospholipids with unsaturated and branched-chain fatty acids cannot be packed tightly because of steric hindrance. Chain length of the lipids also affects fluidity. Low temperature decreases membrane fluidity, as expected. Ca2+ and Mg2+ may diminish the charge repulsion between the phospholipid headgroups; this allows the bilayer molecules to pack together more closely, thereby constraining the motion of the tails and reducing fluidity. Each phospholipid tail occupies about 20–30 Å2 and each headgroup about 60 Å2 (Jain, 1972). Membrane fluidity changes occur in muscle development and in certain disease states, such as cancer, muscular dystrophy (Duchenne type) and myotonic dystrophy.

The hydrophobic portion of local anesthetic molecules may interpose between the lipid molecules. This separates the acyl chain tails of the phospholipid molecules further, reducing the van der Waals forces of interaction between adjacent tails and thus increasing the membrane fluidity. Local anesthetics depress the resting conductance of the membrane and the voltage-dependent changes in gNa, gK and gCa. That is, the local anesthetics produce a non-selective depression of all ionic conductances of the membrane. At the concentration of a local anesthetic required to completely block excitability, its estimated concentration in the lipid bilayer is more than 100 000/μm2. This should be compared with a density of fast Na+ channels of about 20–100/μm2, and even less for K+ channels and Ca2+ channels. Local anesthetics depress Na+,K+-ATPase activity also. Additional information on fluidity is given in several preceding chapters.

IIID Potential Profile across Membrane

The cell membrane has fixed negative charges on its outer and inner surfaces. The charges are presumably due to acidic phospholipids in the bilayer and to protein molecules either embedded in the membrane (islands floating in the lipid bilayer matrix) or tightly adsorbed to the surface of the membrane. Most proteins have an acid isoelectric point, so at a pH near 7.0 they possess a net negative charge. The charge at the outer surface of the cell membrane, with respect to the solution bathing the cell, is known as the zeta potential. This charge is responsible for the electrophoresis of cells in an electric field, the cells moving toward the anode (positive electrode) because unlike charges attract. This surface charge affects the true potential difference (PD) across the membrane, as shown in Fig. 9.2A. At each surface, the fixed charge produces an electric field that extends a short distance into the solution and causes each surface of the membrane to be slightly more negative (by a few millivolts) than the extracellular and intracellular solutions. The potential theoretically recorded by an ideal tiny electrode, as the electrode is driven through the solution perpendicular to the membrane surface, should become negative as the electrode approaches within a few angstroms of the surface. The potential difference between the membrane surface and the solution declines exponentially as a function of distance from the surface. Its length constant is a function of the ionic strength (or resistivity) of the solution: the lower the ionic strength, the greater the length constant. The magnitude of the PD depends on the density of the charge sites (number of chemical groups per unit of membrane area). The number of ionized charge groups is affected by the pH and ionic strength.

FIGURE 9.2 Potential profile across the cell membrane. (A) Because of fixed negative charges (at pH 7.4) at outer and inner surfaces of the membrane, there is a negative potential that extends from the edge of the membrane into the solutions on both sides. This surface potential falls off exponentially with distance into the solution. Magnitude of the surface potential is a function of the charge density. ψo is the electrical potential of the outside solution, ψi . is that of the inside solution and membrane potential (Em) is the difference (ψi−ψo). Em is determined by the equilibrium potentials and relative conductances. Profile of the potential through the membrane is shown as linear (the constant-field assumption), although this need not be true for the present purpose. If the outer surface potential is exactly equal to that in the inner surface, then the true transmembrane potential (E′m ) is exactly equal to the (microelectrode) measured membrane potential (Em). (B) If the outer surface potential is different from the inner potential, e.g. by increasing the extracellular Ca2+ concentration or decreasing the pH to bind Ca2+ or H+ to more of the negative charges, then the E′m is greater than the measured Em. Diminution of the inner surface charge decreases E′m. The membrane ion channels are controlled by E′m.

The membrane potential (Em) measured by an intracellular microelectrode is the potential of the inner solution (ψi) minus the potential of the outer solution (ψo); i.e.:

(9.2)

(9.2)

The true PD across the membrane (E′m), however, is really that PD directly across the membrane, as shown in Fig. 9.2A. If the surface charges at each surface of the membrane are equal, then E′m = Em. If the outer surface charge is decreased to zero by extra binding of protons or cations (such as Ca2+), then the membrane becomes slightly hyperpolarized (E′m > Em), although this is not measurable by the intracellular microelectrode (see Fig. 9.2B). Conversely, if the inner surface charge were neutralized and the outer surface charge restored, then the membrane would become slightly depolarized (E′m < Em). Again, this change is not measurable by the microelectrode, which can only measure the PD between the two solutions.

Because the membrane ionic conductances are controlled by the PD directly across the membrane (i.e. by E′m and not by Em), changes in the surface charges (e.g. by drugs, ionic strength or pH) can lead to apparent shifts in the electrical threshold potential, mechanical threshold potential (the Em value at which contraction of muscle just begins), activation curve and inactivation curve (discussed in subsequent chapters). For example, elevation of extracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]o) is known to raise the threshold potential (i.e. the critical depolarization required to reach electrical threshold), as expected from the small increase in E′m that occurs.

IV Maintenance of Ion Distributions

IVA Resting Potentials and Ion Distributions

The transmembrane potential in resting nerve and muscle cells varies with the type of cell. In myocardial cells, it is about −80 mV (Table 9.1). The resting Em or maximum diastolic potential in cardiac Purkinje fibers is somewhat greater (about −90 mV), whereas that in the nodal cells of the heart is lower (about −60 mV). In nerve cells, the RP is about −70 mV, whereas in mammalian skeletal muscle fibers the value is close to −80 mV. In most smooth muscle cells, the resting Em is about −55 mV.

TABLE 9.1. Comparison of the Resting Potentials in Different Types of Cells

| Cell Type | Resting Potential (mV) |

| Neuron | −70 |

| Skeletal muscle (mammalian) | −80 |

| Skeletal muscle (frog) | −90 |

| Cardiac muscle (atrial and ventricular) | −80 |

| Cardiac Purkinje fiber | −90 |

| Atrioventricular nodal cell | −65 |

| Sinoatrial nodal cell | −55 |

| Smooth muscle cell | −55 |

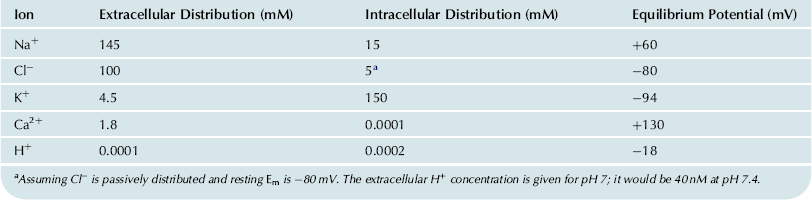

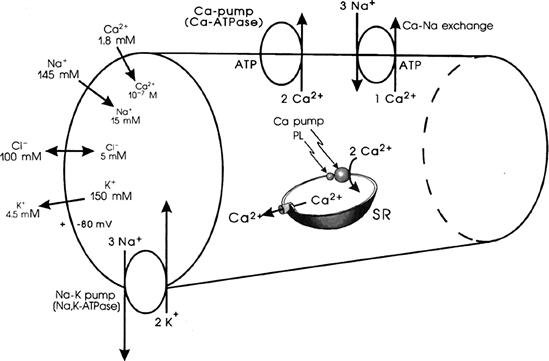

The ionic composition of the extracellular fluid bathing the muscle cells is similar to that of the blood. It is high in Na+ (about 145 mM) and Cl− (about 100 mM), but low in K+ (about 4.5 mM). The Ca2+ concentration is about 2 mM, but about half is bound to serum proteins. In contrast, the intracellular fluid has a low concentration of Na+ (about 15 mM or less) and Cl− (about 6–8 mM), but a high concentration of K+ (about 150–170 mM). These ion distributions are listed in Table 9.2. The free intracellular Ca2+ concentration [Ca2+]i is about 10−7 M or less, but during contraction it may rise as high as 10−5 M. The total intracellular Ca2+ is much higher (about 2 mM/kg), but most of this is bound to molecules, such as proteins, or is sequestered into compartments, such as mitochondria and the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). Most of the intracellular K+ is free and it has a diffusion coefficient only slightly less than that of K+ in free solution. Thus, under normal conditions, the cell maintains an internal ion concentration markedly different from that in the medium bathing the cells and it is these ion concentration differences that underlie the RP and excitability. The existence of the RP enables APs to be produced in those types of cells that have excitability. The ion distributions and related pumps and exchange reactions are depicted in Fig. 9.3.

TABLE 9.2. Summary of the Ion Distributions in Most Types of Cells and the Equilibrium Potentials Calculated from the Nernst Equation

FIGURE 9.3 Intracellular and extracellular ion distributions in a skeletal muscle fiber. Also given are polarity and magnitude of the RP. Arrows give direction of the net electrochemical gradient. Na+-K+ pump is located in the cell surface and the T-tubule membranes. A Ca2+-ATPase/Ca2+ pump, similar to that in the SR, is located in the cell membrane. A Ca2+-Na+ exchange carrier is located in the cell membrane.

Inhibition of the Na+-K+ pump (e.g. by cardiac glycosides such as digitalis) causes the ion concentration gradients gradually to run down or dissipate. The cells lose K+ and gain Na+, Cl− and water. Therefore, the K+ and Na+ equilibrium potentials (EK and ENa) become smaller and the cells become depolarized. The depolarization causes the cells to gain Cl−, and therefore also to gain water because of the resultant gain in osmotic strength, causing the cells to swell.

Although the topic of Na+,K+-ATPase and the Na+-K+ pump is discussed in detail in a subsequent chapter, a brief description is given here.

IVB Na+ and K+ Distribution and the Na+-K+ Pump

The intracellular ion concentrations are maintained differently from those in the extracellular fluid by active ion transport mechanisms that expend metabolic energy to transport specific ions against their concentration (or electrochemical) gradients. These ion pumps are located in the cell membrane at the cell surface and probably also in the transverse tubular membrane of striated muscle cells. The major ion pump is the Na+-K+-linked pump, which pumps Na+ out of the cell against its electrochemical gradient, while simultaneously pumping K+ in against its electrochemical gradient (see Fig. 9.3). The coupling between Na+ and K+ pumping is obligatory, since in zero [K+]o, the Na+ can no longer be pumped out. That is, a coupling ratio of three Na+:0 K+ is not possible. The coupling ratio of Na+ pumped out to K+ pumped in is generally 3:2. The Na+-K+ pump is half-inhibited (Ki value) when [K+]o is lowered to about 2 mM.

If the ratio were 3:3, the pump would be electrically neutral or non-electrogenic. A PD across the membrane would not be produced directly, because the pump would pull in three positive charges (K+) for every three positive charges (Na+) it pushed out. When the ratio is 3:2, the pump is electrogenic and directly produces a PD that causes Em to be greater (more negative) than it would be otherwise, based solely on the ion concentration gradients and relative permeabilities or net diffusion potential (Ediff). A coupling ratio of 3 Na+:1 K+ would produce a greater electrogenic pump potential (Vp). Under normal steady-state conditions, the contribution of the Na+-K+ electrogenic pump potential to Em (ΔVp) is only a few millivolts in myocardial cells; the contribution is greater in smooth muscle cells (6–8 mV) and mammalian skeletal muscle fibers (12–16 mV).

The driving mechanism for the Na+-K+ pump is a membrane ATPase, the Na+,K+-ATPase, which spans the membrane and requires both Na+ and K+ ions for activation. This enzyme requires Mg2+ for activity. ATP, Mg2+ and Na+ are required at the inner surface of the membrane and K+ is required at the outer surface. A phosphorylated intermediate of the Na+,K+-ATPase occurs in the transport cycle, its phosphorylation being Na+-dependent and its dephosphorylation being K+-dependent (for references, see Sperelakis, 1979). The pump enzyme usually drives three Na+ ions out and two K+ ions in for each ATP molecule hydrolyzed. The Na+,K+-ATPase is specifically inhibited by the cardiac glycosides (digitalis drugs) acting on the outer surface. The pump enzyme is also inhibited by vanadate ion and by sulfhydryl (SH) reagents (such as N-ethylmaleimide [NEM], mercurial diuretics and ethacrynic acid), thus indicating that the SH groups are crucial for activity.

Blockade of the Na+-K+ pump produces only a small immediate effect on the resting Em: a small depolarization of about 2–16 mV, depending on cell type, representing the contribution of Vp to Em (ΔVp). Because excitability and generation of APs are almost unaffected at short times, excitability is independent of active ion transport. However, over many minutes, depending on the ratio of surface area to volume of the cell, the resting Em slowly declines because of gradual dissipation of the ionic gradients. The progressive depolarization depresses the rate of rise of the AP, and hence the propagation velocity and eventually all excitability is lost. Thus, a large RP and excitability, although not immediately dependent on the Na+-K+ pump, are ultimately dependent on it.

The rate of Na+-K+ pumping in excitable cells must change with the amount of electrical activity to maintain relatively constant intracellular ion concentrations. A higher frequency of APs results in a greater overall movement of ions down their electrochemical gradients and these ions must be repumped to maintain the ion distributions. For example, the cells tend to gain Na+, Cl− and Ca2+ and to lose K+. The factors that control the rate of Na+-K+ pumping include [Na+]i and [K+]o. In cells that have a large surface area to volume ratio (such as small-diameter non-myelinated axons), [Na+]i may increase by a relatively large percentage during a train of APs and this would stimulate the pumping rate. Likewise, an accumulation of K+ externally occurs and this also stimulates the pump. The Km value for K+, i.e. the concentration for half-maximal rate, is about 2 mM. It has been shown that [K+]o is significantly increased during the long AP plateau in cardiac muscle.

IVC Cl− Distribution

In many nerve and muscle cells, Cl− ion does not appear to be actively transported; i.e. there is no Cl− ion pump. In such cases, Cl− distributes itself passively (no energy used) in accordance with Em. Consequently, ECl is equal to Em in a resting cell. For example, in mammalian myocardial cells, Cl− seems to be close to passive distribution, because [Cl−]i. is at, or only slightly above, the value predicted by the Nernst equation from the resting Em (for references, see Sperelakis, 1979). When passively distributed, [Cl−]i is low because the negative potential inside the cell (the RP) pushes out the negatively-charged Cl ion (like charges repel) until the Cl− distribution is at equilibrium with the resting Em. Hence, for a resting Em of −80 mV and taking [Cl−]o to be 100 mM, [Cl−]i calculated from the Nernst equation would be 4.9 mM.

(9.3)

(9.3)

During the AP, the inside of the cell goes in a positive direction and a net Cl− influx (outward Cl− current, ICl) will occur and thus increase [Cl−]i. The magnitude of the Cl− influx depends on the Cl− conductance (gCl) of the membrane:

(9.4)

(9.4)

The average level of [Cl−]i in excitable cells should depend on the frequency and duration of the AP, i.e. the mean Em averaged over many AP cycles.

In some smooth muscles, [Cl−]i is much higher (e.g. 30 mM) than the value of 12.5 mM predicted from passive distribution:

The elevated [Cl−]i in smooth muscle could be due to an exchange carrier (e.g. Cl−–HCO3− exchange) or to a co-transporter (e.g. Na+-K+-Cl− transport).

IVD Ca2+ Distribution

IVD1 Need for Calcium Pumps

For the positively-charged Ca2+ ion, there must be some mechanism for removing it from the cytoplasm. Otherwise, the cell would continue to gain Ca2+ until there was no electrochemical gradient for net influx of Ca2+. Ca2+ loading would occur until the free [Ca2+]i in the cytoplasm was even greater than that outside (ca. 2 mM) because of the negative potential inside the cell. Therefore, there must be one or more Ca2+ pumps in operation. The SR (or ER) membrane contains a Ca2+-activated ATPase (which requires Mg2+ for activity) that actively pumps two Ca2+ ions from the cytoplasm into the SR lumen at the expense of one ATP. This pump ATPase is capable of pumping down the Ca2+ to less than 10−7 M. The Ca2+-ATPase of the SR is regulated by an associated low-molecular-weight protein, phospholamban. Phospholamban is phosphorylated by cyclic-AMP-dependent protein kinase and, when phosphorylated, stimulates the Ca2+-ATPase and Ca2+ pumping (by a derepression process). The sequestration of Ca2+ by the SR is essential for muscle relaxation. The mitochondria also can actively take up Ca2+ almost to the same degree as the SR, but this Ca2+ pool probably does not play an important role in normal excitation–contraction coupling.

The resting Ca2+ influx and the extra Ca2+ influx that enters with each AP must be returned to the interstitial fluid. Two mechanisms have been proposed for this: (1) a Ca2+-ATPase, similar to that in the SR, is present in the sarcolemma; and (2) a Ca2+-Na+ exchange occurs across the cell membrane. It has been reported that there is a Ca2+-ATPase in the sarcolemma of myocardial cells (Dhalla et al., 1977; Jones et al., 1980) and smooth muscle (Daniel et al., 1977) that actively transports two Ca2+ outward against an electrochemical gradient, using one ATP in the process.

IVD2 Cai - Nao Exchange Reaction

The Cai - Na o exchange reaction exchanges one internal Ca2+ ion for three external Na+ ions via a membrane carrier molecule (see Fig. 9.3). This reaction is facilitated by ATP, but ATP is not hydrolyzed (consumed) in this reaction. Instead, the energy for the transport of Ca2+ against its large electrochemical gradient comes from the Na+ electrochemical gradient. That is, the uphill transport of Ca2+ is coupled to the downhill movement of Na+. Effectively, the energy required for this Ca2+ movement is derived from the Na+,K+-ATPase. Thus, the Na+- K+ pump, which uses ATP to maintain the Na+ electrochemical gradient, indirectly helps to maintain the Ca2+ electrochemical gradient. Hence, the inward Na+ leak is greater than it would be otherwise. A complete discussion of Ca2+-Na+ exchange is given in a subsequent chapter.

The energy cost (ΔGCa, in joules/mole) for pumping out Ca2+ ion is directly proportional to its electrochemical gradient. These energetic equations are as follows (where ΔG is the change in free energy, z is the valence, and F is the Faraday constant):

(9.5)

(9.5)

The energy available from the Na+ distribution is directly proportional to its electrochemical gradient.

(9.6)

(9.6)

Depending on the exact values of [Na+]i and [Ca2+]i in a muscle cell at rest, the energetics would be about adequate for an exchange ratio of 3 Na+:1 Ca2+. An exchange ratio of 3:1 would produce a small depolarization due to a net inward flow of current (3 Na+ in to 1 Ca2+ out) via this electrogenic Cai2+-Nao+ exchanger. That is, there is a net positive charge moving inward for every cycle of the exchanger. This net exchanger current can be measured in whole-cell voltage-clamp studies when all ionic currents and Na+-K+ pump currents are blocked.

The exchange reaction depends on relative concentrations of Ca2+ and Na+ on each side of the membrane and on relative affinities of the binding sites to Ca2+ and Na+. Because of this exchange reaction, whenever the cell gains Na+, it will also gain Ca2+, because the Na+ electrochemical gradient is reduced and the exchange reaction becomes slowed. The Cai2+- Nao+ exchange process has been proposed as the mechanism of the positive inotropic action (i.e. more forceful contraction) in the heart resulting from cardiac glycoside inhibition of the Na+-K+ pump.

In addition, when the myocardial cell membrane is depolarized during the AP plateau, the exchange carriers will exchange the ions in reverse, namely, internal Na+ for external Ca2+ and thus increase Ca2+ influx. The net effect of this mechanism is to elevate [Ca2+]i . Such reversed Cao2+-Nai+ exchange appears to be a significant source of Ca2+ for contraction in cardiac muscle of some species.

V Equilibrium Potentials

VA Equivalent Electrical Circuit

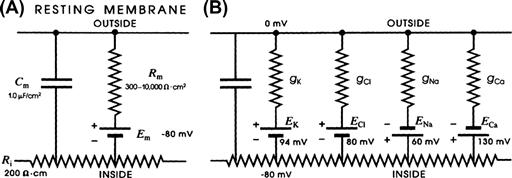

The electrical equivalent circuit of the cell membrane at rest is depicted in Fig. 9.4. In Fig. 9.4A, the membrane is indicated as a parallel resistance (Rm) and capacitance (Cm). The capacitance results from the lipid bilayer matrix of the membrane and the resistance or conductance (Gm) results from the protein ion channels floating in the lipid bilayer and spanning across it. The RP is depicted as a battery in series with Rm, with the negative pole facing inside the cell.

FIGURE 9.4 Electrical equivalent circuits for a cell membrane at rest. (A) Membrane as a parallel resistance-capacitance circuit, the membrane resistance (Rm) being in parallel with the membrane capacitance (Cm). Resting Em is represented by a −80 mV battery in series with the membrane resistance, the negative pole facing inward. (B) Membrane resistance is divided into its four component parts, one for each of the four major ions of importance: K+, Cl−, Na+ and Ca2+. Resistances for these ions (RK, RCl, RNa and RCa) are parallel to one another and represent totally separate and independent pathways for permeation of each ion through the resting membrane. These ion resistances are depicted as their reciprocals, namely, ion conductances (gK, gCl, gNa, gCa). Equilibrium potential for each ion (e.g. EK), determined solely by the ion distribution in the steady state and calculated from the Nernst equation, is shown in series with the conductance path for that ion. RP of −80 mV is determined by the equilibrium potentials and by the relative conductances.

In Fig. 9.4B, the equivalent circuit for the resting membrane is shown further expanded, by breaking up the membrane conductance (Gm) into its four component parts, one for each ion of major importance electrophysiologically, namely K+, Cl−, Na+ and Ca2+. The respective conductances are gK, gCl, gNa, and gCa. The equilibrium potential (E) for each ion is placed in series with the conductance pathway for that ion, as depicted. The polarity of each battery is as shown; namely, the pole facing inwards is negative for K+ and Cl− and positive for Na+ and Ca2+. These polarities are based on the directions of the concentration gradients and charge on the ions.

VB Nernst Equation

For each ionic species distributed unequally across the cell membrane, an equilibrium potential (Ei) or battery can be calculated for that ion from the Nernst equation (for 37°C),

(9.7a)

(9.7a)

(9.7b)

(9.7b)

(9.7c)

(9.7c)

where Ci is the internal concentration of the ion, Co is the extracellular concentration, R is the gas constant (8.3 J/mol/K), T is the absolute temperature in Kelvins (K = 273+°C), F is the Faraday constant (96 500 Coul/eq), and z is the valence (with sign). Thus, zF = Coul/mol. Taking the RT/F constants and the factor of 2.303 for conversion of natural log (ln), or log to the base of e (2.717), to log to the base of 10 (log10) gives:

(9.7d)

(9.7d)

Therefore, the Nernst equation (Equation 9.7a) becomes

(9.7e)

(9.7e)

(9.7f)

(9.7f)

The −61 mV constant (2.303 RT/F) becomes −59mV at 22°C. A derivation of the Nernst equation is given in the Appendix to this chapter. The Nernst equation gives the potential difference (PD) (electrical force) that would exactly oppose the concentration gradient (diffusion force).

Only very small charge separation (Q, in coulombs) is required to build a very large PD.

(9.8)

(9.8)

where Cm is the membrane capacitance. This is further discussed in the next section.

For the ion distributions given previously (see Table 9.2), the approximate equilibrium potentials are:

The sign of the equilibrium potential represents the inside of the cell with reference to the outside (see Fig. 9.4). Because Na+ is higher outside (ca. 145 mM) than inside (ca. 15 mM), the positive pole of the Na+ battery (ENa) is inside the cell. The concentration gradient for Ca2+ is in the same direction as for Na+ (1.8 mM [Ca2+]o and about 1×10−7 M [Ca2+]i,) and so the positive pole of ECa is inside. K+ is higher inside (ca. 150 mM) than outside (ca. 4.5 mM) and so the negative pole is inside. Because Cl− is higher outside (ca. 100 mM) than inside (ca. 5 mM), the negative pole is inside. Voltages are, by convention, given for the inside with respect to the outside.

VC Concentration Cell

In a concentration cell (essentially a two-compartment system separated by a membrane), the side of higher concentration becomes negative for cations (positive ions) and positive for anions (negative ions). Any ion whose equilibrium potential is different from the RP (e.g. −80 mV for a myocardial cell or skeletal muscle fiber) is off equilibrium and therefore must effectively be pumped at the expense of energy. In many cell types, only Cl− ion appears to be at or near equilibrium, whereas Na+, Ca2+ and K+ are actively transported. Even H+ ion is off equilibrium, EH being closer to zero potential (see Table 9.2). If H+ were passively distributed, the negative intracellular potential would pull in more H+ ions, causing [H+]i to increase, making the cell interior more acidic.

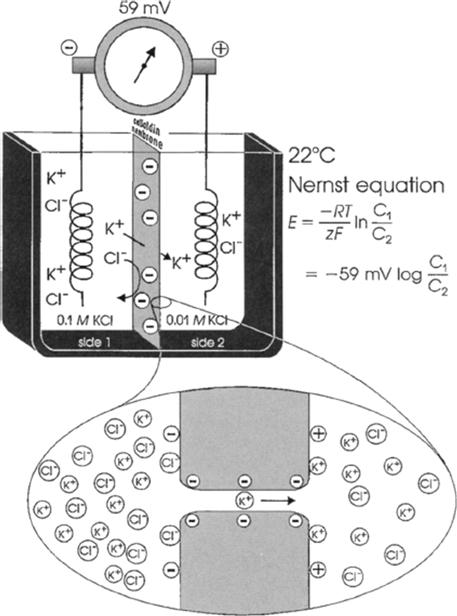

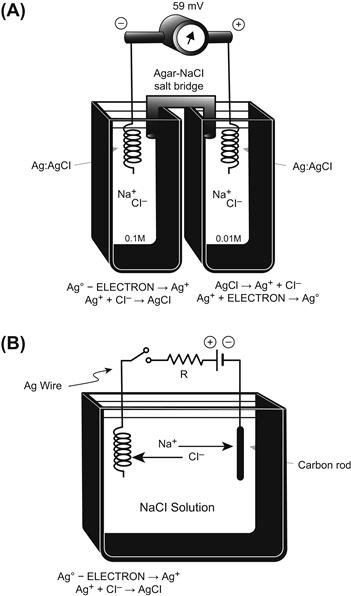

The mechanism for development of the equilibrium potential is depicted in Fig. 9.5. To show the development of an equilibrium potential, we can use an artificial membrane (e.g. one made of celloidin) to separate two solutions, i.e. to form a concentration cell. This membrane contains negatively-charged pores, which therefore allows cations (like K+) to pass through, but prevents anions (like Cl−) from passing. This is because like charges repel one another and unlike charges attract one another. Therefore, in this particular membrane, K+ is permeant and Cl− is impermeant. If one side (side 1) contains a salt like KCl at a concentration higher (e.g. 0.10 M) than that in the other side (side 2) (e.g. 0.01 M), then a steady PD is very quickly built up across the membrane. As calculated from the Nernst equation, for a 10-fold difference in concentration of the permeant monovalent cation (K+), the PD would be −61 mV at 37°C (or −59 mV at a room temperature of 22°C).

FIGURE 9.5 Upper diagram: concentration cell diffusion potential developed across artificial membrane containing negatively-charged pores. The membrane is impermeable to Cl− ions, but permeable to cations such as K+. Concentration gradient for K+ causes a potential to be generated, the side of higher K+ concentration becoming negative. Lower diagram: expanded diagram of water-filled pore in the membrane, showing the permeability to K+ ions, but lack of penetration of Cl− ions. Potential difference is generated by charge separation, a slight excess of K+ ions being held close to the right-hand surface of the membrane; a slight excess of Cl− ions is aggregated close to the left surface.

This PD is between the two solutions and expressed across the membrane. Side 1 (side of highest K+ concentration) becomes negative with respect to side 2. The PD is developed because of the tendency for diffusion (diffusion force) from high concentration to low concentration. This is based on the random thermal motion of the ions (particles), somewhat related to Brownian motion of larger particles. That is, the side of higher concentration has a greater probability of K+ ions moving from side 1 to side 2 than in the reverse direction, based on the greater number of particles, all moving in random directions. Therefore, there will be a loss of positive charges (K+ ions) from side 1 and a gain of positive charges in side 2.

Because negative charges (Cl− ion) cannot accompany the positive charges, as the membrane was made impermeable to anions, a charge separation is built up across the membrane. It can now be readily understood why side 1, the side of higher cation concentration, becomes negatively charged (due to loss of positive charges) and why side 2, the side of lower cation concentration, becomes positively charged (due to gain of positive charges). The charge separation is very tiny and they stay plastered very close to the membrane. That is, for the example depicted in Fig. 9.5, side 1 will have the small excess of Cl− ions held very close to the membrane and side 2 will have the small excess of K+ ions held very close to the membrane. The force holding them there is called the electrostatic or Coulombic force, based on the attraction between unlike charges. This is related to Coulomb’s law and the nature of capacitors.

In the two bulk solutions, the law of electroneutrality is upheld; i.e. for every cation (K+) there is a nearby anion (Cl−). Thus, the charge separation occurs only directly across the membrane and is very tiny with respect to the total number of charges in the two solutions. In fact, after equilibrium is reached (within a few seconds), the most sensitive chemical analyses would fail to detect the very slight decrease in K+ in side 1 or gain of K+ on side 2.

Thus, the system comes to equilibrium quickly and with very little charge (K+ and Cl−) separation. That is, K+ does not continue to have a net movement from side 1 to side 2 until the concentrations become equal. Why not? The answer is that the small charge separation produces a large PD across the membrane and this PD is in such a polarity that it antagonizes further net movement of K+ from side 1 to side 2. That is, the positive voltage that is developing on side 2 repels the positively-charged K+ ions because like charges repel. At equilibrium, these two forces become equal and opposite and there is no further net movement of ions. Unidirectional fluxes of K+ ions would still occur (because of their random thermal motion), but these would be equal and opposite and so no further net flux would occur.

In the example selected, KCl was used. However, any salt, such as NaCl, CaCl2 or Na2SO4, could have been illustrated. If a divalent cation like Ca2+ were used, then from the Nernst equation, the same 10-fold concentration gradient would develop a potential of only half, namely 30.5 mV (37°C) or 29.5 mV (22°C). The reason that this factor is half, rather than double as one might guess from the fact that the charge is double, is that the Nernst equation gives the PD that exactly opposes the diffusion force due to the concentration gradient, as stated in the paragraph above. Therefore, because the charge is double, only half the voltage is necessary to oppose effectively the concentration force. If the cation in question were trivalent, such as La3+, then the 2.303 RT/zF factor would be one-third of 61 mV, or about 20.3 mV. It is for this reason that it is convenient to give the Nernst equation in the form shown in Equation 9.7c, namely with the factor (at 37°C) being −61 mV/z. This allows easy calculation of the equilibrium potential for an ion of any charge and sign (polarity).

That is, the sign and charge should be used, for example, +1 for K+ or Na+, +2 for Ca2+ and −1 for Cl−. When the ion in question is an anion like Cl−, then −1/−1 gives a plus (+). Because [Cl−]o >[Cl−]i, this concentration ratio can be inverted by changing the sign of the 2.30 RT/zF factor back to negative (−). That is, changing the sign of the factor in front of a log ratio simply inverts the ratio.

Finally, if the concentration cell depicted in Fig. 9.5 were made with a membrane that had positively-charged pores, then everything would be reversed. The membrane would be permeable to Cl− and impermeable to K+ and ECl would be +59 mV (at 22°C) and +61 mV (at 37°C). Again, the voltage is given for side 1 with respect to side 2. Thus, in dealing with an anion, the side of higher concentration becomes positive (due to a small loss of Cl−) and the side of lower concentration becomes negative (due to a small gain of Cl−). The separated charges again are plastered very close to the membrane: K+ ions on side 1 and Cl− ions on side 2.

VD Activity Coefficient

Thus, an equilibrium potential can be calculated for any species of ion that is distributed unequally across a membrane. All that one needs to know are the concentrations in the two solutions and the charge (and temperature). Actually, we should use the activity (a) of the ion in question in the two solutions, instead of concentration. Thus, the Nernst equation given in Equation 9.7c becomes (for K+, for example):

The activity of an ion (in molar) can be obtained by multiplying the concentration of the ion (in molar) by the activity coefficient (γ) for the ion:

(9.9)

(9.9)

In the biological case, the activity coefficients are relatively close to 1.0 (e.g. 0.7–0.9) for Na+, K+ and Cl− in both the extracellular and intracellular solutions. Therefore, in these cases, using the concentrations gives a good approximation. However, in the case of Ca2+, the activity coefficient in the intracellular solution especially is substantially lower and so this would affect the calculated value of ECa.

VE Nernst–Planck Equation

The basic Nernst equation has been modified in several ways for special situations. For example, in the concentration cell depicted in Fig. 9.5, a cell in which a single salt (both ions of same valence) is distributed across the membrane at two different concentrations, the PD developed across the membrane (Em) can be calculated from the equation:

(9.10)

(9.10)

where [salt]1 and [salt]2 are the concentrations of the salt on side 1 and side 2 and Uc and Ua are the mobilities of the cations and anions, respectively, through the membrane. Thus, when the mobilities (or permeabilities) of the cation and anion are equal (Uc = Ua), Em is zero, regardless of the equilibrium potentials. When the anion is impermeable (Ua = 0), the mobility fraction in Equation 9.10 becomes 1.0 and the equation reduces to the simple Nernst equation. When the cation is impermeable (Uc = 0), the fraction becomes −1.0 and the same numerical value of Em is produced, but of opposite sign. Equation 9.10 can be used to calculate Em for any combination of Ua and Uc. For example, if Ua = 0.5 Uc, then for the problem illustrated in Fig. 9.5, Em would be about −20 mV (side 1 negative). Thus, the membrane potential is related to the relative mobilities.

VF Energy Wells

Ions do not just “fall” through a water-filled pore in the membrane (protein ion channel) down an electrochemical gradient. Instead, an ion may bind to several charged sites on its journey through the channel pore. The K+ ion depicted in the bottom of Fig. 9.5, for example, is shown as binding to three negatively-charged sites within the pore. These may be considered energy wells and the ion must gain kinetic energy to become dislodged from this energy well to pass over the next energy barrier and into the next energy well. This energy comes from the ion being hit by another ion just entering the pore, producing a billiard-ball effect. Some evidence for this model was presented in Chapter 8, which discusses the Ussing flux ratio equation.

From the measured value of the conductance of single ion channels (e.g. 20 pS, range of 10–300 pS), how many ions that pass through a single channel per second can be estimated. This number is about 6 000 000 ions/s. Therefore, the average transit time for a single ion to cross the membrane (50–70 Å thick) is about 0.17 μs.

VI Electrochemical Driving Forces and Membrane Ionic Currents

VIA Electrochemical Driving Forces

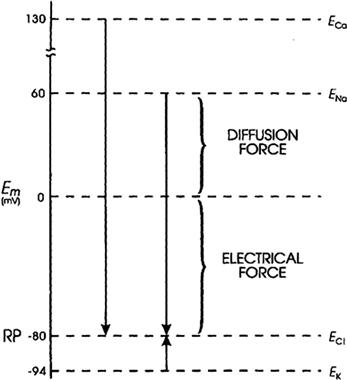

The electrochemical driving force for each species of ion is the algebraic difference between its equilibrium potential, Ei, and the membrane potential, Em. The total driving force is the sum of two forces: an electrical force (the negative potential in a cell at rest tends to pull in positively-charged ions, because unlike charges attract) and a diffusion force (based on the concentration gradient) (Fig. 9.6); i.e.:

(9.11a)

(9.11a)

Thus, in a resting cell, the driving force for Na+ is:

(9.11b)

(9.11b)

The negative sign means that the driving force is directed to bring about net movement of Na+ inward. The driving force for Ca2+ is very large and is directed inward:

(9.11c)

(9.11c)

The driving force for K+ is:

(9.11d)

(9.11d)

Hence, the driving force for K+ is small and directed outward. The driving force for Cl− is nearly zero for a cell at rest in which Cl− is passively distributed (e.g. neuron, myocardial cell, skeletal muscle fiber); i.e.:

(9.12)

(9.12)

However, during the AP, when Em is changing, the driving force for Cl− becomes large and there is a net driving force for inward Cl− movement (Cl− influx is an outward Cl− current). Similarly, the driving force for K+ outward movement increases during the AP, whereas those for Na+ and Ca2+ decrease.

FIGURE 9.6 Representation of the electrochemical driving forces for Na+, Ca2+, K+, and Cl−. Equilibrium potentials for each ion (e.g. ENa) (calculated from the Nernst equation for their extracellular and intracellular concentrations) are positioned vertically according to their magnitude and sign. Measured RP is assumed to be −80 mV. Electrochemical driving force for an ion is the difference between its equilibrium potential (Ei) and the membrane potential (Em), i.e. (Em−Ei). Thus, at rest, the driving force for Na+ is the difference between ENa and the resting Em. If ENa is +60 mV and resting Em is −80 mV, the driving force is 140 mV. That is, the driving force is the algebraic sum of the diffusion force and the electrical force and is represented by the length of the arrows in the diagram. Driving force for Ca2+ (about 210 mV) is even greater than that for Na+, whereas that for K+ is much less (about 14 mV). Direction of the arrows indicates the direction of the net electrochemical driving force, namely, the direction for K+ is outward, whereas that for Na+ and Ca2+ is inward. If Cl− is passively distributed, then its distribution across the cell membrane is determined by the net membrane potential. For a cell sitting a long time at rest, ECl = Em and there is no net driving force.

VIB Membrane Ionic Currents

The net current for each ionic species (Ii) is equal to its driving force times its conductance (gi, reciprocal of the resistance) through the membrane. This is essentially Ohm’s law:

(9.13)

(9.13)

Ohm’s law must be modified to reflect the fact that, in an electrolytic system, the total force tending to drive net movement of a charged particle must take into account both the electrical force and the concentration (or chemical) force. Thus, for the four ions, the net current can be expressed as:

(9.14)

(9.14)

(9.15)

(9.15)

(9.16)

(9.16)

(9.17)

(9.17)

In a resting cell, Cl− and Ca2+ can be neglected and the Na+ current (inward) must be equal and opposite to the K+ current (outward) to maintain a steady resting potential:

(9.18a)

(9.18a)

(9.18b)

(9.18b)

Thus, although in the resting membrane the driving force for Na+ is much greater than that for K+, gK is much larger than gNa, so the currents are equal. Hence, there is a continuous leakage of Na+ inward and K+ outward, even in a resting cell, and the system would run down if active pumping were blocked. Because the ratio of the Na+ to K+ driving forces (−140 mV/−14 mV) is 10, the ratio of conductances (gNa/gK) will be about 1:10. The fact that gK is much greater than gNa accounts for the RP being close to EK and far from ENa.

VII Determination of Resting Potential and Net Diffusion Potential (Ediff)

VIIA Determining Factors

For given ion distributions, which normally remain nearly constant under usual steady-state conditions, the resting potential (RP) is determined by the relative membrane conductances (g) or permeabilities (P) for Na+ and K+ ions. That is, the RP (of about −80 mV in cardiac muscle or skeletal muscle) is close to EK (about −94 mV) because gK>>gNa or PK>>PNa. There is a direct proportionality between P and g at constant Em and concentrations. From simple circuit analysis (using Ohm’s law and Kirchhoff’s laws), one can prove that the membrane potential will always be closer to the battery (equilibrium potential) having the lowest resistance (highest conductance) in series with it (see Figs. 9.4 and 9.6). In the resting membrane, this battery is EK, whereas in the excited membrane it will be ENa (or ECa), because there is a large increase in gNa and/or gCa during the AP.

Any ion that is passively distributed cannot determine the RP; instead, the RP determines the distribution of that ion. Therefore, Cl− is not considered for myocardial cells, skeletal muscle fibers and neurons because it seems to be passively distributed. However, transient net movements of Cl− across the membrane do influence Em; e.g. washout of Cl− (in Cl−-free solution) produces a transient depolarization and reintroduction of Cl− produces a transient hyperpolarization. Cl− movement is also involved in the production of inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs) (see chapter on synaptic transmission).

Because of its relatively low concentration, coupled with its relatively low resting conductance, the Ca2+ distribution has only a relatively small effect on the resting Em and can be ignored.

VIIB Constant-Field Equation

A simplified, but most useful, version of the Goldman–Hodgkin–Katz constant-field equation can be given (for 37°C):

(9.19)

(9.19)

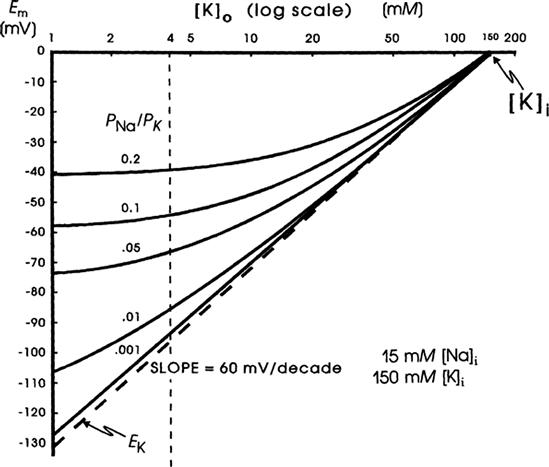

This equation shows that for a given ion distribution, the resting Em is determined by the PNa/PK ratio, the relative permeability of the membrane to Na+ and K+. For myocardial cells and skeletal muscle fibers, the PNa/PK ratio is about 0.04, whereas for nodal cells of the heart and smooth muscle cells, this ratio is closer to 0.10 or 0.20.

Inspection of the constant-field equation shows that the numerator of the log term will be dominated by the [K+] term [since the (PNa/PK) [Na+]i term will be very small], whereas the denominator will be affected by both the [K+]o and (PNa/PK) [Na+]o terms. This relationship thus accounts for the deviation of the Em versus log [K+]o curve from a straight line (having a slope of 61 mV/decade) in normal Ringer solution (Fig. 9.7). When [K+]o is elevated ([Na+]o being reduced by an equimolar amount), the denominator becomes more and more dominated by the [K+]o term and less and less by the (PNa/PK) [Na+]o term. Therefore, in bathing solution containing high K+, the constant-field equation approaches the simple Nernst equation for K+ and Em approaches EK. As [K+]o is raised stepwise, EK becomes correspondingly reduced, because [K+]i stays relatively constant; therefore, the membrane becomes more and more depolarized (see Fig. 9.7). Sometimes, however, some hyperpolarization is produced at a [K+]o level between 5 and 9 mM. In addition, lowering [K+]o to 0.1 mM often produces a prominent depolarization. These effects are usually explained on the basis that: (1) PK is reduced in low [K+]o; and (2) an electrogenic Na+-K+ pump potential is inhibited at a low [K+]o (Km of about 2 mM).

FIGURE 9.7 Theoretical curves calculated from the Goldman constant-field equation for RP (Em) as a function of [K+]o. Family of curves is given for various PNa/PK ratios (0.001, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1 and 0.2). K+ equilibrium potential (EK) calculated from the Nernst equation (broken straight line). Curves calculated for a [K+]i of 150 mM and a [Na+]i of 15 mM. Calculations made holding [K+]o + [Na+]o constant at 154 mM; i.e. as [K+]o was elevated, [Na+]o was lowered by an equimolar amount. Possible change in PK as a function of [K+]o was ignored. Point at which Em is zero gives [K+]i. The potential reverses in sign when [K+]o exceeds [K+]i.

A more detailed discussion of the constant-field equation is given in the Appendix to this chapter.

When [K+]o is elevated (e.g. to 8 mM) in some types of cells, a hyperpolarization of up to about 10 mV may be produced. Such behavior is often observed in cells with a high PNa/PK ratio (due to low PK) and therefore a low resting Em, such as in young embryonic chick hearts. This hyperpolarization could be explained by several factors: (1) stimulation of the electrogenic Na+ pump current (Ip); (2) an increase in PK (and therefore gK) due to [K+]o effect on PK; and (3) an increase in gK (but not PK) due to the concentration effect. A similar explanation may apply to the fall-over in the Em versus log [K+]o curve when [Ko] is lowered to 1 mM and less, hence depolarizing the cells. This effect is prominent in rat skeletal muscle, for example (see Fig. 7 of chapter on skeletal muscle excitability).

VIIC Chord Conductance Equation

An alternative method of approximating the membrane resting potential (Em) is the chord conductance equation. The word chord means a straight line connecting two points on a curve, and here specifically refers to the average slope of a non-linear steady-state voltage–current curve, i.e. a straight line from any point on the curve through the origin (zero applied current). (In contrast, slope conductance is the tangent at any point on the curve.) Thus:

(9.20a)

(9.20a)

where gK, gNa, gCl, and gCa are the membrane conductances for K+, Na+, Cl−, and Ca2+, respectively, and Σg is the total conductance (sum of all ionic partial conductances). The ratio of gK/Σg, for example, is the relative or fractional conductance for K+.

The chord conductance equation can conveniently take into account all ions, including divalent cations, that are distributed unequally across the membrane. The ions important to membrane potentials (including APs, postsynaptic potentials and receptor potentials) are K+, Na+, Cl− and Ca2+. As discussed previously, Cl− cannot help in determining the RP if it is passively distributed. Thus, Equation 9.20a can be rewritten, omitting the Cl− term, as:

(9.20b)

(9.20b)

For simplicity, we can ignore the Ca2+ term also, giving:

(9.20c)

(9.20c)

where Σg is now equal to gK + gNa.

The chord conductance equation can be derived simply from Ohm’s law and from circuit analysis for the condition when net current is zero (INa + IK = 0). (See the Appendix to this chapter for the derivation.) The equation holds true whenever the net current across the membrane is zero, as for the RP.

The chord conductance equation is useful for giving the membrane potential when the ion conductances and distributions are known. For example, at the neuromuscular junction, the neurotransmitter acetylcholine opens the gates of many ionic channels that allow both Na+ and K+ to pass through equally well (i.e. gNa = gK). Hence, the potential that the postsynaptic membrane tends to seek when maximally activated (i.e. the equilibrium potential or so-called reversal potential for the end-plate potential, EPP) is:

(9.20d)

(9.20d)

A disadvantage of the chord conductance equation is that it gives nearly a straight line for the Em versus log [K+]o plot (actually a slight bend in the opposite direction at low [K+]o). In contrast, the constant-field equation gives the complete bending of the curves (for different PNa/PK ratios).

The chord conductance equation again illustrates the important fact that the gK/gNa ratio determines the RP. When gK»gNa, then Em is close to EK; conversely, when gNa»gK (as during the spike part of the AP), Em shifts to close to ENa or to ECa (in the case of smooth muscle cells).

The chord conductance equation can be rewritten using resistances instead of conductances and may then be called the chord resistance equation:

(9.20e)

(9.20e)

where RK and RNa are the K+ and Na+ resistances, which are the reciprocals of the conductances. Note that, in this equation, the positions of the two batteries are interchanged. This equation can be derived by simply substituting the two reciprocals into the chord conductance equation. It can also be derived by circuit analysis, as discussed in the Appendix to this chapter. This Appendix section also shows how circuit analysis can be used to determine what the RP should be, without using either the Goldman constant-field equation or the chord conductance equation.

VIID Net Diffusion Potential, Ediff

In the presence of ouabain (short-term exposure only) to inhibit the Na+-K+ pump and Vp, the RP that remains reflects the net diffusion potential, Ediff. Ediff is determined by the ion concentration gradients for K+ and Na+ and by the relative permeability for K+ and Na+. When the Na+-K+ pump is operating, there is normally a small additional contribution of Vp to the resting Em of about 2–16 mV, depending on cell type (discussed in the following section).

Inhibition of the Na+-K+ pump for long periods will gradually run down the ion concentration gradients. The cells lose K+ and gain Na+ and therefore EK and ENa become smaller. The cells thus become depolarized (even if the relative permeabilities were unaffected), which causes them to gain Cl− (because [Cl]i was held low by the large resting potential), and therefore, to also gain water (cells swell).

VIII Electrogenic Sodium Pump Potentials

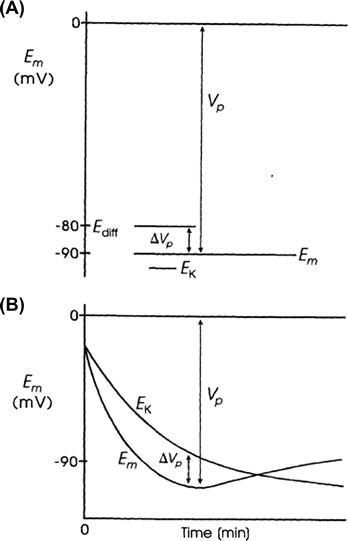

A brief summary of the previous principles is as follows: the Na+–K+ pump is responsible for maintaining the cation concentration gradients. The equilibrium potentials for K+ (EK) and Na+ (ENa) are about −94 mV and +60 mV, respectively. The RP value is usually near EK, because the K+ permeability (PK) is much greater than PNa in a resting membrane. The exact resting membrane potential (Em) depends on the PNa/PK ratio, myocardial cells and skeletal muscle fibers having PNa/PK ratios of 0.01–0.05, whereas smooth muscle or nodal cells of the heart have a ratio closer to 0.10–0.15. In the various types of cells, the resting Em has a smaller magnitude (i.e. is less negative) than EK by 10–40 mV. If there were no electrogenic pump potential contribution to the RP (i.e. as though the Na+-K+ pump was only indirectly responsible for the RP by its role in producing the ionic gradients), Em would equal Ediff.

However, a direct contribution of the pump to the resting Em can be demonstrated. For example, if the Na+-K+ pump is blocked by the addition of ouabain, there usually is an immediate depolarization of 2–16 mV, depending on the type of cell. Thus, the direct contribution of the electrogenic Na+-K+ pump to the measured resting Em is small under physiologic conditions (but very important).

However, under conditions in which the pump is stimulated to pump at a high rate (e.g. when [Na+]i or [K+]o is abnormally high), the direct electrogenic contribution of the pump to the RP can be much greater and Em can actually exceed EK by as much as 20 mV or more. For example, if the ionic concentration gradients are allowed to run down (e.g. by storing the tissues in zero [K+]o and at low temperatures for several hours), then after the tissues are allowed to restart pumping, the measured Em can exceed the calculated EK (e.g. by 10–20 mV) for a time (Fig. 9.8). The Na+ loading of the cells is facilitated by placing them in cold low or zero [K+]o solutions, because external K+ is necessary for the Na+-K+-linked pump to operate; Km of the Na+,K+-ATPase for K+ is about 2 mM. After several hours in such a solution, the internal concentrations of Na+, K+ and Cl− approach the concentrations in the bathing Ringer solution and the RP is very low (<−30 mV).

FIGURE 9.8 Diagrammatic representation of an electrogenic sodium pump potential. (A) Muscle fiber in which the net ionic diffusion potential (Ediff, function of ion equilibrium potentials and relative conductances) is −80 mV, yet exhibits a measured RP (Em) that is greater. Difference between Em and Ediff represents the contribution of the electrogenic pump to the RP. The electrogenic pump potential must be equal to Vp. The contribution of the electrogenic pump potential to the RP (Em−Ediff) is equal to ΔVp. (B) Fiber that was run down (Na+ loaded, K+ depleted) over several hours by inhibition of Na+-K+ pumping, resulting in a low RP. Returning the fiber to a pumping solution allows the resting Em to rebuild as a function of time. Buildup in Em occurs faster than buildup in EK, as illustrated.

The cells are then transferred to a pumping solution, which is the appropriate Ringer solution containing normal K+ and at normal temperature. Under such conditions, the pump turns over at a maximal rate, because the major control over pump rate is [Na+]i and [K+]o. The low initial Em also stimulates the pump rate, because the energy required to pump out Na+ is less. The measured Em of such Na+ preloaded cells increases rapidly and more rapidly than EK, as shown in Fig. 9.8. After this transient phase, however, a crossover of the two curves occurs, so that EK again exceeds Em, as in the physiologic condition. Cardiac glycosides prevent or reverse the transient hyperpolarization beyond EK. The possibility that ionic conductance changes (e.g. an increase in gK or a decrease in gNa) can account for the observed hyperpolarization, can be ruled out whenever Em exceeds (is more negative than) EK.

Rewarming cells previously cooled leads to the rapid restoration of the normal RP (within 10 min), whereas recovery of the intracellular Na+ and K+ concentrations is slower. During prolonged hypoxia, the RP of cardiac muscle decreases much less than EK decreases (a difference of about 25 mV). This is because the electrogenic pump attempts to hold the RP constant, despite dissipating ionic gradients.

Another method used to demonstrate that the pump is electrogenic is to inject Na+ ions into the cell through a micropipette. This procedure rapidly produces a small transient hyperpolarization, which is prevented by ouabain. The pump current and the rate of Na+ extrusion increase in proportion to the amount of Na+ injected. To prove that the pump is electrogenic, it must be demonstrated that the hyperpolarization produced in an intact muscle is not the result of enhanced pumping of an electroneutral pump. This could cause depletion of external K+ in a restricted diffusion space just outside the cell membrane, leading to a larger EK and thereby to hyperpolarization. Depletion could occur if the Na+-K+ pump pumped in K+ faster than it could be replenished by diffusion from the bulk interstitial fluid.

The electrogenic Na+ pump is influenced by the membrane potential. From energetic considerations, depolarization should enhance the electrogenic Na+ pumping, whereas hyperpolarization should inhibit it. This is because depolarization reduces the electrochemical gradient (and hence the energy requirements) against which Na+ must be extruded, whereas hyperpolarization increases the gradient. Thus, there should be a distinct potential, more negative than EK, at which Na+ pumping is prevented (e.g. a pump equilibrium potential). A value close to −140 mV was reported for cardiac cells and rat skeletal muscle fibers.

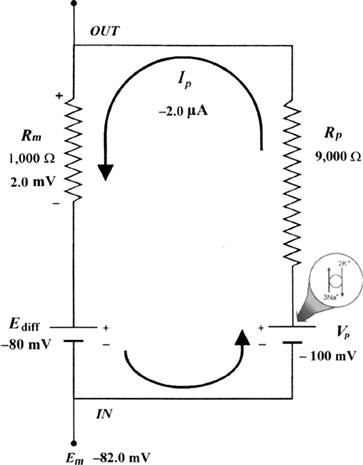

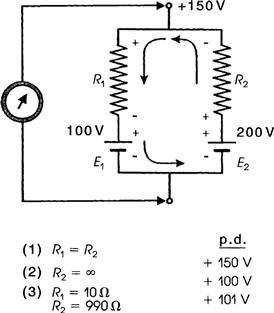

Any method used to increase membrane resistance increases the contribution of the pump to the RP (Fig. 9.9). That is, the electrogenic Na+ pump contribution is augmented under conditions that increase membrane resistance. The contribution of the pump potential to the measured Em is the difference in Em when the pump is operating versus that immediately after the pump has been stopped by the addition of ouabain or zero [K+]o. Consequently, it appears as though the contribution from the electrogenic pump potential (ΔVp) is in series with the net cationic diffusion potential (Ediff):

(9.21)

(9.21)

where Ip is the electrogenic component of the pump current and Ediff is the Em that would exist solely on the basis of the ionic gradients and relative permeabilities in the absence of an electrogenic pump potential. Equation 9.21 states that Em is the sum of Ediff and a voltage (IR) drop produced by the electrogenic pump current across Rm. The electrogenic pump potential (Vp) can be considered to be in parallel with Ediff (see Fig. 9.9). Because the density of pump sites is more than a 1000-fold greater than that of Na+ and K+ channels in resting membrane, there is no relation between the pump pathway (the active flux path) and Rm (the passive flux paths); i.e. the pump path and the passive conductance paths are in parallel. The pump potential should be considered the full potential between zero and the maximum negative pump potential (Vp) while the pump is pumping (see Fig. 9.8).

FIGURE 9.9 Hypothetical electrical equivalent circuit for electrogenic sodium pump. Model consists of a pump pathway in parallel with the membrane resistance (Rm) pathway. This model fits the evidence that the pump proteins and channel proteins are embedded in the lipid bilayer as parallel elements. Net diffusion potential (Ediff, determined by the ion equilibrium potentials and relative permeabilities) of −80 mV is depicted in series with Rm. Pump leg is assumed to consist of a battery in series with a fixed resistor (pump resistance, Rp) that does not change with changes in Rm and whose value is about ninefold higher than Rm. Pump battery is charged up to some voltage (e.g. Vp of −100 mV) by a pump current generator. Net electrogenic pump current is developed by the pumping in of only two K+ ions for every three Na+ ions pumped out. For the values given in the figure (namely, Rm of 1000 Ω, Ediff of −80 mV, Rp of 9000 Ω, and Vp of −100 mV), circuit analysis shows that the measured membrane potential (Em) is −82.0 mV: i.e. the direct electrogenic pump potential contribution to the RP is −2.0 mV. The calculated pump current (Ip) is −2.0 μA.

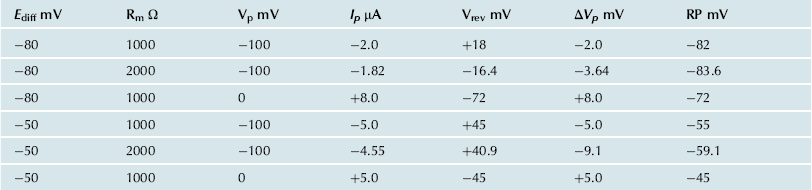

One possible equivalent circuit for an electrogenic Na+ pump that takes into account some of the known facts is given in Fig. 9.9. The pump pathway is in parallel with the resistance pathways. The pump resistance (Rp) is estimated to be about ninefold higher than Rm. If so, the pump resistance acts to minimize a short-circuit path to Ediff when the pump potential is low or zero (pump inhibited). The pump potential contribution to Em (ΔVp) is a function of membrane resistance (Rm); the higher the Rm (Rp constant), the more nearly Em approaches Vp. The pump battery is charged to some voltage by a pump current generator. If the pump is stopped by ouabain, Vp goes to zero. Using circuit analysis for the values of the parameters given in Fig. 9.9, Em would be −82.0 mV, moderately close to Ediff (−80 mV) (Table 9.3). If Rm is raised twofold (to 2000 Ω), Em would be −83.6 mV. Thus, this circuit clearly gives a pump potential contribution to Em that is dependent on Rm. The higher Rm is relative to Rp, the more Em reflects Vp. If Ediff is made smaller (e.g. in smooth muscle cells having a higher PNa/PK ratio), then the relative contribution of the pump potential to Em becomes greater (see Table 9.3).

TABLE 9.3. Summary of Calculations of Resting Potential (Em) for a Model Having an Electrogenic Pump Potential (Vp) in Parallel with Net Diffusion Potential (Ediff), as Depicted in Figure 9.9

Pump resistance, Rp, was assumed to have constant value of 9000 Ω. Rm, membrane resistance; ΔVp contribution of Vp to the measured Em. Em was calculated from the equation

In general, Cl− ions are known to have a “short-circuiting” effect on the electrogenic Na+ pump potential. For example, if the external Cl− is replaced by less permeant anions, the magnitude of the hyperpolarization produced by the electrogenic Na+ pump is substantially increased. This Cl− effect could be caused by the lowering of membrane resistance in the presence of Cl−. The greater the Rm, the greater the contribution of the electrogenic pump potential to resting Em (see Fig. 9.9 and Table 9.3).

The density of Na+-K+ pump sites, estimated by specific binding of [3H]ouabain, is usually about 700–1000/μm2. The turnover rate of the pump is generally estimated to be 20–100/s. The pump current (Ip) has been estimated as:

(9.22)

(9.22)

where ΔVp is the pump potential contribution. Values of about 20 pmol/(cm2/s) were obtained. A density of 1000 sites/μm2 (1011 sites/cm2) times a turnover rate of 40/s gives 4×1012 turnovers/(cm2/s). If three Na+ are pumped with each turnover, this gives 12×1012 Na+ ions/(cm2/s); dividing by Avogadro’s number (6.02×1023 ions/mol) yields 20×10−12 mol/(cm2/s), which is the same value as the 20 pmol/(cm2/s) measured. The net pump current would be less, depending on the amount of K+ pumped in the opposite direction, i.e. depending on the coupling ratio (e.g. 3 Na+:2 K+). Whenever the Na+-K+ pump is stimulated to turn over faster, e.g. by increasing [Na+]i or [K+]o, the electrogenic pump current is increased.

Ion flux (J) can be converted to current (I) by the relationship:

(9.23)

(9.23)

Thus, a flux of 20 pmol/(cm2/s) is equal to approximately 2 μA/cm2 (20×10−12 mol/(s/cm2)×0.965×105 coul/mol). Since ΔVp =

= Ip×Rm, if Rm were 1000 Ω/cm2 and Ip were 2 μA/cm2, the electrogenic pump contribution to Em would be 2 mV (Em = Ediff + IpRm).

Ip×Rm, if Rm were 1000 Ω/cm2 and Ip were 2 μA/cm2, the electrogenic pump contribution to Em would be 2 mV (Em = Ediff + IpRm).

Two K+ ions are usually carried in for every three Na+ ions moved out. Because the pump is electrogenic, i.e. produces a net current (and hence potential) across the membrane, then the amount of K+ pumped in must be less than the amount of Na+ pumped out; e.g. the Na+/K+ coupling ratio must be 3:2 (or 3:1). The coupling ratio cannot be 3:0, because of the well-known fact that external K+ must be present for the pump to operate. The coupling ratio might be increased under some conditions, e.g. when [Na+]i is elevated. If the coupling ratio were to increase (e.g. to 3:1), the pump potential contribution would become larger, for a constant pumping rate.

The pump current may be stimulated by increasing the turnover rate of each pump site or by increasing the number of pump sites. In skeletal muscle, insulin has been reported to increase the number of Na+-K+ pump sites in the sarcolemma by increasing the rate of translocation from an internal pool, thereby increasing the pump current. β-Adrenergic agonists, like isoproterenol, stimulate the pump current by cyclic AMP/protein kinase-A phosphorylation of the pump.

The electrogenic pump potential has physiologic importance in cells. Although small, the electrogenic pump potential contribution to the RP could have significant effects on the level of inactivation of the fast Na+ channels and hence on propagation velocity. Further, an electrogenic pump potential could act to delay depolarization under adverse conditions (e.g. ischemia and hypoxia) and would act to speed repolarization of the normal RP during recovery from the adverse conditions. It is crucial that the excitable cell maintain its normal RP as much as possible, because of the effect of small depolarizations on the AP rate of rise and conduction velocity and the complete loss of excitability with larger depolarizations. For example, the rate of firing of pacemaker nodal cells of the heart is affected significantly by very small potential changes.

In cells in which there are lower RPs (e.g. smooth muscle cells and cardiac nodal cells), the electrogenic pump potential contribution can be larger (see Table 9.3). Sinusoidal oscillations in the Na+-K+ pumping rate could produce oscillations in Em, which could exert important control over the spontaneous firing of the cell. The period of enhanced pumping hyperpolarizes the cell and suppresses automaticity, whereas slowing of the pump leads to depolarization and consequently to triggering of APs. Oscillation of the pump rate would be brought about by oscillating changes in [Na+]i. For example, the firing of several APs should raise [Na+]i (these cells have a small volume to surface area ratio) and stimulate the electrogenic pump. The increased pumping rate, in turn, hyperpolarizes and suppresses firing, thus allowing [Na+]i to decrease again and removing the stimulation of the pump; the latter condition depolarizes and triggers spikes and the cycle is repeated. In rabbit sinoatrial nodal cells, it was concluded that the electrogenic Na+ pump is one factor that modulates the heart rate under physiologic conditions. When stimulated at a high rate, cardiac Purkinje fibers and nodal cells undergo a transient period of inhibition of automaticity after cessation of the stimulation, known as overdrive suppression of automaticity. Stimulation of the electrogenic pump due to elevation in [Na+]i is the major cause of this phenomenon.

Appendix

AI More Details on Ca2+-Na+ Exchanger

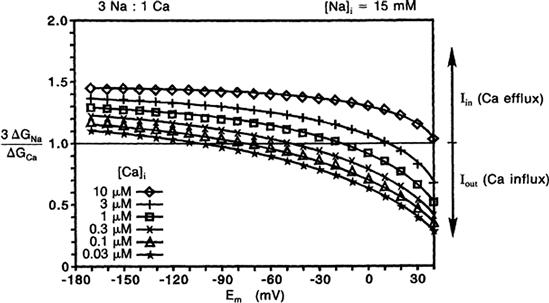

The ratio of free energy changes for Na+ to Ca2+ was calculated for a coupling ratio of 3 Na+:1 Ca2+ (3 ΔGNa/ΔGCa) and a [Na+]i of 15 mM, and plotted as a function of membrane potential, for different [Ca2+]i levels (Fig. 9A.1). This plot allows an assessment of how the directionality of the exchanger is affected by Em, i.e. forward mode versus reverse mode of operation, and how the reversal potential of the exchanger is shifted by [Ca2+]i. When the ratio is 1.0, 3ΔGNa = −ΔGCa and the sum equals zero: 3 ΔGNa+−ΔGCa = 0. Therefore, the exchanger would be at equilibrium. For ΔG ratios >1.0, there is a net inward current carried by Na+ ion, coupled with net Ca2+ efflux from the cell. This represents forward mode of operation of the exchanger. For ΔG ratios <1.0, there is a net outward current carried by Na+ ion, coupled to a net Ca2+ influx into the cell. This represents reverse mode of operation of the exchanger.