Chapter 16

Cosmic Structure

Galaxies are the building blocks of cosmic structure. Astronomer Sir William Herschel, working in the late 18th/early 19th century, using his 6m (20 ft) and 12m (40 ft) telescopes, glimpsed what this structure would look like. Before then galaxies, as we know them today, were merely indistinct smudges of light seen between the brighter foreground stars of the Milky Way. Herschel had already discovered that some of the nebulae were ‘full of stars’. He called them ‘Island Universes’. By meticulously cataloguing their locations, he soon found hundreds of them clustering among the stars in the constellations Coma Berenices and Virgo. Herschel called these curious collections ‘clouds’. It would not be until the first decades of the 20th century that their true distances and speeds were determined by means of spectroscopic and stellar studies. This was a tedious process involving measuring the Doppler speeds of each faint galaxy and assigning a distance to it based on a growing number of distance gauges, known as ‘standard candles’ (see page 202).

William Herschel was a polymath musician, optician and astronomer who made substantial contributions to observational astronomy in the late 18th century.

Galaxies often come in pairs or small groups, such as our own Milky Way with its two Magellanic Clouds, or the companion galaxies to the Andromeda Galaxy. Among the earliest renderings of close galaxy pairs was that of Lord Rosse, using his ‘Great Telescope’ at Birr Castle, Ireland, which first went into service in 1845.

A more dazzling compact group is Stephan’s Quintet in the constellation Pegasus located 280 million light years away, discovered in 1877 by French astronomer Édouard Stephan.

Earliest drawing of the close pair of galaxies in Messier 51 by the Earl of Rosse.

Stephan’s Quintet provides a rare opportunity to observe a galaxy group in the process of collision and merging into a single elliptical galaxy in the distant future.

At first, it was not known what to make of these pairings. Many might merely represent two galaxies along the same line of sight but not physically related to one another. It was not until the mid-1950s, when it became possible to calculate distances and velocities to galaxies, that it was clear that many of these systems were actually close to one another. Their shapes strongly hinted at profound gravitational interactions taking place between them. This led to the idea that some galaxy pairs and groups may actually be colliding systems of stars and gas.

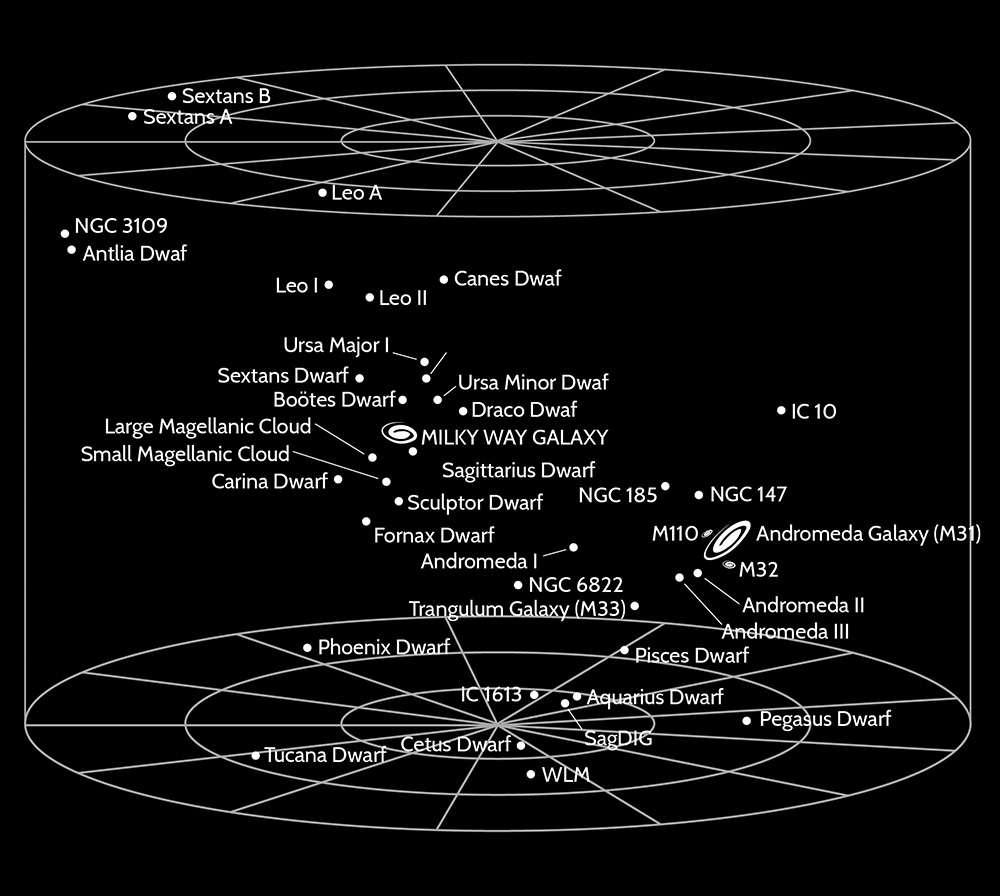

By the early 1900s, it was already known that our own Milky Way was a member of a group of a dozen nearby galaxies including the Andromeda Galaxy as its other major member. Edwin Hubble, in his 1936 book The Realm of the Nebulae, referred to this collection as the ‘Local Group’. Since that time, the Local Group has swelled to over 54 members. Most of these galaxies are of the dwarf variety – merely clusters of a few billion faint stars. A few are dramatic, and highly-photogenic, spiral systems such as Andromeda (Messier 31) and Triangulum (Messier 33). The Sagittarius Dwarf Irregular Galaxy is at the farthest gravitational outskirts of the Local Group some 3.4 million light years from the Milky Way and is barely detectable photographically.

The Sagittarius Dwarf Irregular Galaxy is probably typical of the largest numbers of galaxies in the universe.

The question then arose, are groups and clusters of galaxies in the universe ubiquitous? Because of their substantial extent across the sky, a systematic search for more examples of galaxy groups and clusters had to await better photographic technology. Between 1949 and 1958, and under the guidance of Edwin Hubble, among others, the National Geographic Society commissioned the first all-sky photographic survey (POSS I) using the new 120 cm (48 in) Schmidt Telescope at Mount Palomar, in California. These photographs recorded images of billions of stars and galaxies and offered the data in a convenient format of pairs of ‘red’- and ‘blue’-filtered glass plates. This archive became the workhorse for generations of astronomers searching for the optical candidates for exotic radio and X-ray sources, as well as studies in galactic nebulae and extra-galactic structure.

George Abell was one of the first astronomers to systematically tackle the problem of the numbers and structures of galaxy clusters by using the POSS archive. His catalogue eventually identified over 4,000 galaxy clusters in the northern and southern hemispheres, and characterized them in terms of their richness and concentration.

Edwin Hubble confirmed through observations at Lick Observatory that galaxies were beyond the Milky Way and were receding from the Milky Way at high speed as a result of cosmic expansion.

Galaxy clusters vary enormously in their physical sizes as well as the numbers of members they contain. Our Local Group would barely make it into Abell’s Richness Class 0. But clusters like the Coma Cluster or the Virgo Cluster discovered by Herschel in the 18th century tipped the limits of Richness Class 5 with well over 1000 galaxies each. The largest cluster known by 2018 is SPT-CLJ2106-5844, located 7.5 billion light years from the Milky Way, with a mass equal to 1.3×1015 suns. This would equal about 5,000 galaxies like our Milky Way, or easily ten times that number if most member galaxies are simple dwarfs, as for our Local Group.

Although the typical distances between member galaxies can be a million light years for less concentrated clusters, the most compact clusters may have average distances of only a few times the diameters of the member galaxies. At typical cluster speeds of 300 km/s, collisions between galaxies can be frequent over the multi-billion-year ages for these clusters. This leads to enormous changes to the space within the cluster. Low-speed collisions cause the galaxies to gently merge. But high-speed collisions can cause the gas, dust and clouds that make up the galactic interstellar medium (ISM) to be ejected from the galaxies and take up residence in the intra-cluster medium (ICM). This medium will be very hot due to the kinetic energy deposited into the gas as thermal energy. The gas, mostly hydrogen, may be so hot that it is ionized and is detected only through its X-ray emissions.

A consequence of a dense ICM is that other member galaxies passing through this material may themselves be dramatically affected. We can see this in the case of the galaxy ESO-137 located within the Abell 3627 cluster.

The preponderance of spindle-shaped ‘lenticular’ galaxies in some clusters may attest to the dramatic sweeping-out of a galaxy’s ISM due to an ICM gas, leaving behind a dead galaxy with no new star-forming activity or dusty ISM.

George Abell discovered the clustering of galaxies and systematically catalogued the largest galaxy clusters within a few billion light years of the Local Group.

Superclusters

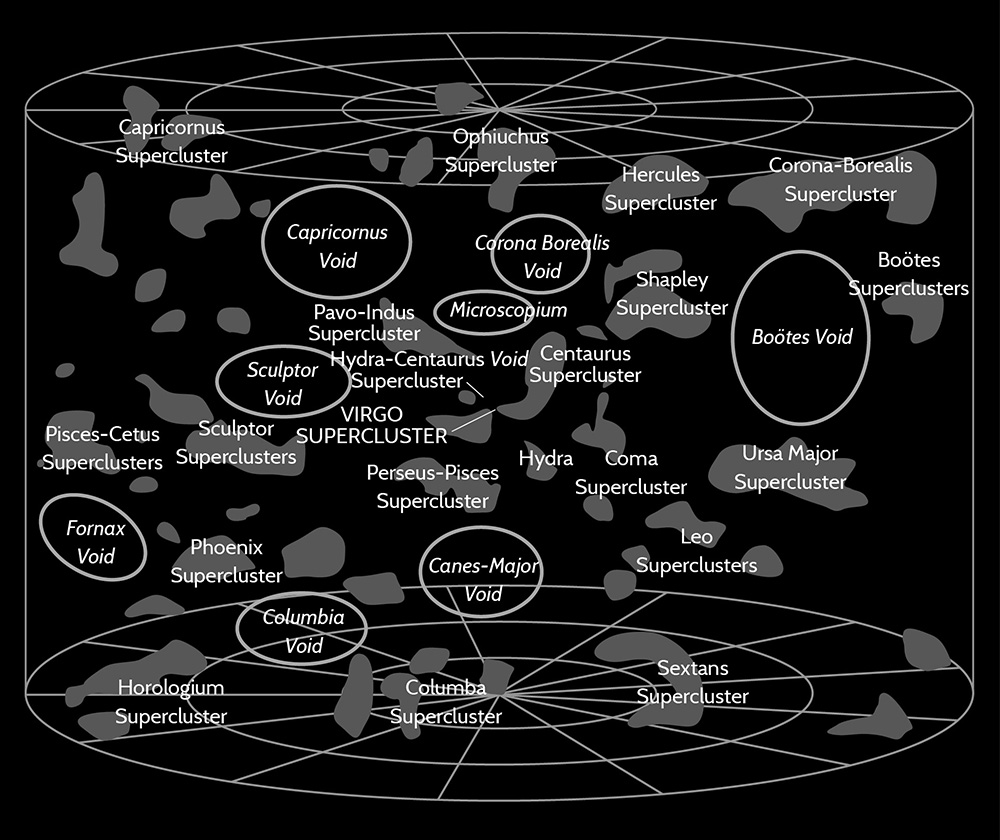

When Abell plotted the locations of these catalogued clusters on a map of the entire sky, he was able to discern that they were not at all randomly distributed, but in many cases displayed higher-order clustering. Not only were galaxies found largely in clusters of varying size, but these clusters themselves combined with others across the sky to form clusters of clusters. By 1953, astronomer Gerard de Vaucouleurs had already discovered such large groupings in his study of our Local Group and its relationship with the Virgo Cluster. He found that galaxies within 200 million light years of the centre of the Virgo Cluster formed a flattened system he called the Local Supercluster.

In the 1960s and 70s, further investigations of Abell Clusters and the distribution of local galaxy clusters soon revealed a vast tapestry of superclusters, some far larger than our nearby Virgo Supercluster, and extending nearly 1 billion light years from the Milky Way. But what was so interesting about the distribution of these superclusters was that they were not randomly distributed across space as one might have expected from the assumptions of Big Bang cosmology. Instead, they were preferentially found along inconceivably vast filamentary structures encompassing still more mysterious empty regions called Voids. One of the largest of these, the Bootes Void, was discovered by Robert Kirchner in 1981 and is located about 700 million light years from the Milky Way. Spanning some 300 million light years, its interior is almost completely devoid of galaxies. Had the Milky Way been located at its centre, we would not have discovered the existence of other galaxies in the universe until the mid-1900s!

The Local Group includes our own Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy along with more than 50 other galaxies within 4 million light years of the Milky Way. The majority of these are classified as dwarf galaxies.

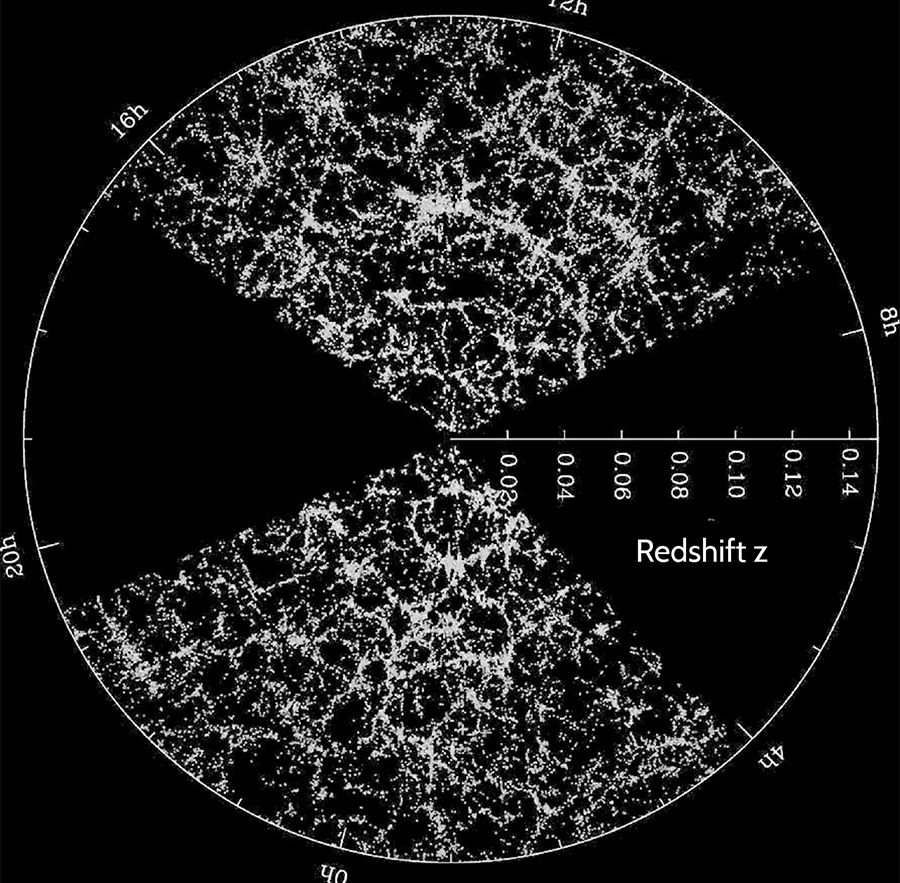

The investigation of superclusters, cosmic filaments and voids had to await newer observational techniques developed in the 1970s to massively increase the catalogue of galaxies for which Doppler shifts, or more accurately redshifts, could be determined. Because the local universe contained millions of galaxies, the older and time-consuming methods of one-at-a-time measuring had to be dramatically enhanced. The first astronomers to develop these techniques were Marc Davis, John Huchra and Margaret Geller at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), whose ‘Z-Machine’ could generate 30 redshifts every night. The CfA1 Redshift Survey, begun in 1977, catalogued over 2,000 galaxies. The follow-on CfA2 survey completed its work in the mid-1980s and added an additional 18,000 galaxies to the sample. These path-breaking surveys created nearly complete slices of the universe for bright galaxies, revealing not only the integrity and limits to many local superclusters, but delineating the scale of many voids as well.

Additional, even larger, surveys of fainter galaxies were completed during the heyday of redshift research in the 1990s and 2000, with even more efficient technologies becoming available including large-format digital cameras and fibre-optic, multi-channel spectrometers capable of calculating one thousand redshifts at a time. For example, the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) Main Galaxy Sample, completed in 2002, determined redshifts for over 100,000 galaxies across one-sixth of the sky. Subsequent SDSS surveys will increase this to over one million galaxies.

The local superclusters and voids constitute the dominant large-scale structures in the universe with galaxies and galaxy groups found within filamentary concentrations surrounding voids in which few galaxies exist.

What has emerged from this cartography of the universe during the last half of the 20th century is that galaxies are preferentially found within superclusters, which themselves form cosmic filaments surrounding a complex and even foam-like patina of voids. The origin of this structure is deeply embedded in events taking place near the Big Bang itself.

The cataloguing of millions of galaxy redshifts allowed astronomers to investigate the motions of galaxies and their complex gravitational interactions spanning millions of light years of intergalactic space. Galaxies, in essence, became test particles that traced out gravitational flows of cosmic matter. This effort, enhanced by powerful supercomputer calculations based on Newtonian gravity and general relativity, led to the mapping of the local cosmic velocity field.

A comparison of the CfA and Sloan Redshift Surveys which shows that individual galaxies are generally located along filamentary concentrations of clusters and superclusters spanning the local universe.

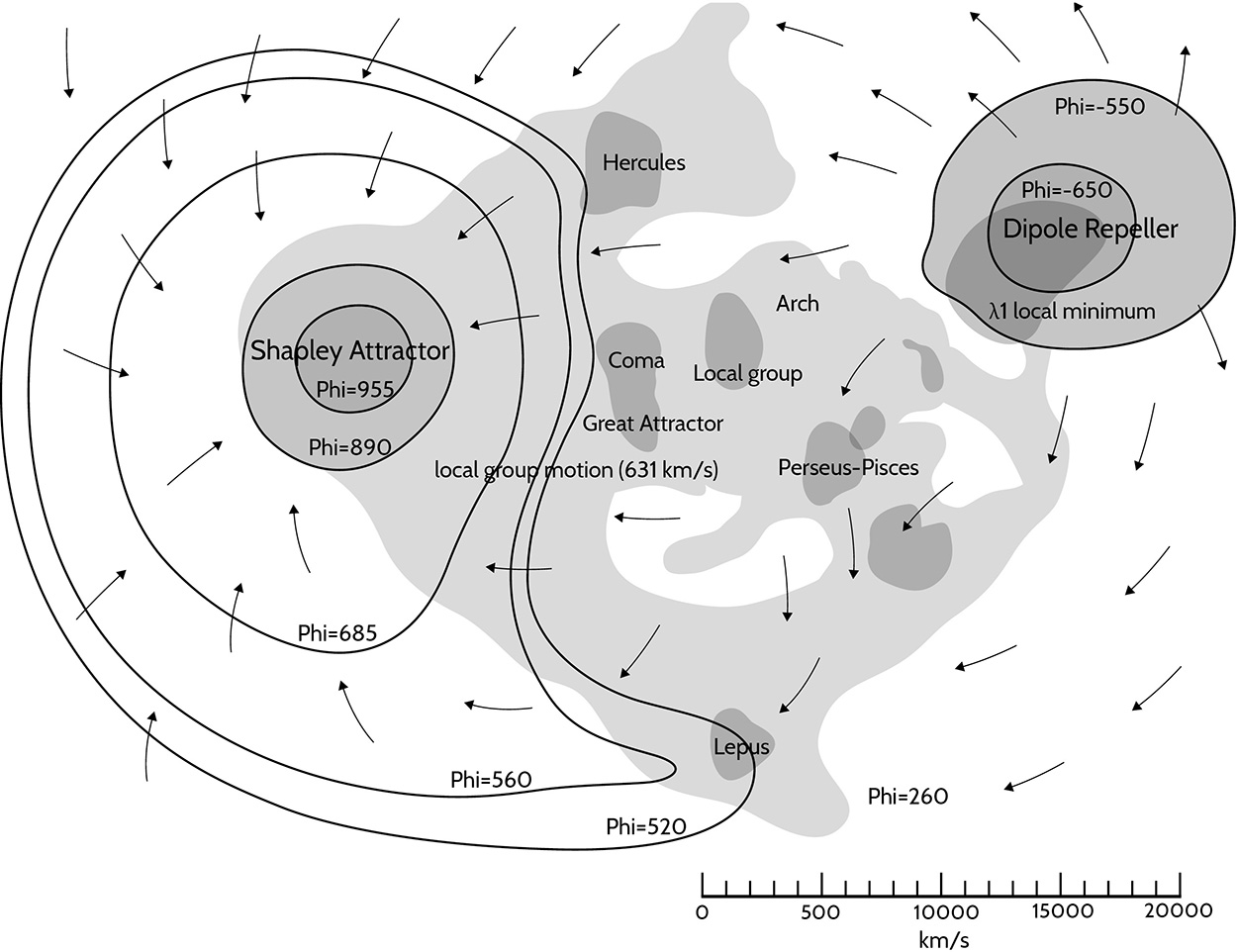

Since the 1980s, astronomers have known that the Local Group is falling into the Virgo Supercluster and that this entire ensemble of thousands of galaxies is in turn moving towards a distant concentration of matter called the Great Attractor. Behind it and much farther away is another huge concentration of galaxies called the Shapley Supercluster. In addition to these flows of matter, there is also a region of reduced mass discovered in 2017 by astronomer Yehuda Hoffman called the Dipole Repeller, because galaxy motions seem to be emanating from this region of space. In fact, because gravity is only attractive, this means that the ‘Repeller’ region is actually a volume of space containing very little matter – a huge cosmic void much larger than the Bootes Void.

Data from thousands of local galaxies reveal a net doppler movement in the direction of the Shapley Supercluster.

Key Points

• Galaxies are collections of billions of stars and form the most elementary basis for structure in the universe.

• Galaxies often appear in pairs, groups and clusters which can have thousands of member galaxies. Our Milky Way is a member of the Local Group of galaxies.

• Clusters of galaxies often appear in larger groups called superclusters consisting of dozens or hundreds of separate clusters of galaxies.

• Clusters and superclusters form filamentary shapes spanning hundreds of millions of light years and surrounding vast voids in space where few galaxies are found.

• The large-scale structure of the cosmos is determined by the distribution of dark matter which accounts for most of the gravitating material in the universe.