The construction of the Temple of Jupiter would have required an enormous workforce. The effort required to dig nearly thirty-two thousand cubic meters of earth from the Capitoline Hill for the foundations; to quarry, transport, and lay the vast stone substructure with such precision; and to create an apparatus to stack the stone walls and columns, construct the elaborate roof, and fashion thousands of terracotta tiles, revetments, antefixes, and other decorations could only have occurred so quickly with a surplus of labor. It should therefore come as no surprise that immediately after completion of the temple, more and more monuments built with stone walls and columns and impressive terracotta roofs went up across the city. With so many workers unoccupied after decades of building, and with such sophisticated tectonic principles in play, there would be a new need to give builders work and a new excess of well-trained artists and builders to go around. Beginning with what some have called the Capitoline Era, Rome had become a city where sophisticated architecture was the new normal.1 Some of the response to this comfort with the new architecture has already been seen, in the reconstructions of the Comitium, Regia, Atrium Vestae, and monumental houses around the turn of the century. After 500, construction did not let up. If anything, it redoubled as two monumental temples went up in the Forum, several others were built on the hilltops, and another truly exceptional sanctuary nearly equal in size to the Temple of Jupiter joined the urban image at the riverside. What is more, to service the growing city, its monumental architecture, and the evident increase in political and economic activity, a new tide of infrastructure—including vast paved plazas and roads—joined these works, bestowing permanence and refinement on the city’s public spaces.

Evidence for architecture on the Capitoline and Palatine from ca. 500–450 is almost exclusively in the form of fictile revetments with little or no context for architectural design. Although they create a frustratingly piecemeal record of urban change, the fragments are nonetheless revealing of impressive change on the hilltops.

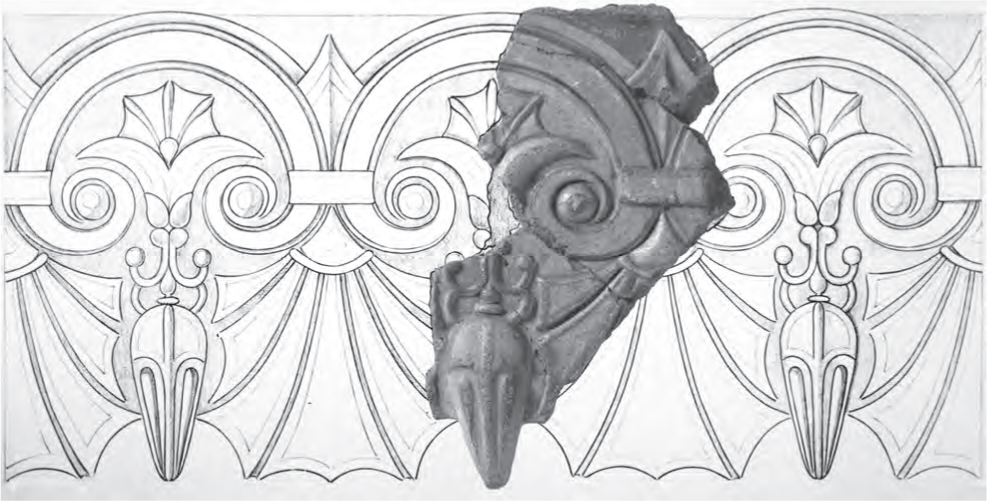

Excavation near the site of the Temple of Jupiter uncovered numerous fragments of anthemion revetments with lotus buds, palmettes, and interlocking volutes as well as openwork crestings, which constitute part of an extensive program of terracotta decoration for at least one other large religious building on the summit of that hill dating to the early fifth century.2 One particularly well-preserved fragment is composed of hanging palmettes stylized in a fan shape, alternating with long, hanging lotus buds surmounted by vertical lotus flowers (fig. 99). The hanging palmettes are held by interlocking volutes that arc over the buds and flowers. The fragment matches revetments from Segni, the Temple of Juno, and especially Satricum, Temple II (figs. 100, 101).3 All three are composed of the same motif. Three arched, flat ribbons join together by way of thin bands, which hold hanging palmettes. The ribbons curl at either side of the base of each palmette to form volutes. Beneath each arched ribbon is an upright lotus blossom above a hanging lotus bud. In all three examples, the anthemion relief measures approximately twenty-five to twenty-six centimeters tall, and the similar size of the revetments is attended at Satricum and Segni by similarly monumental dimensions in the temples they adorned. Satricum’s Temple II measures twenty-one meters wide, while the Temple of Juno at Segni measures twenty-four meters wide, both substantial in size: in fact, among the most monumental of the region.4 As with other examples of similar sculpted roof decoration and architectural remains throughout Central Italy, the comparative evidence is telling. The revetments are far larger than those used on smaller temples at Velletri and S. Omobono in Rome, and not as sizable as those on rare, truly outsized buildings, such as the Temple of Jupiter at Rome. They are used only on temples of impressive dimensions, and they indicate a temple of monumental size, similar to others in Central Italy at Pyrgi, Ardea, and Caere. Sadly, any precise details about the plan of the Roman building will remain a mystery until further excavation is performed, but the construction of a second substantial religious building atop the Capitoline in the first decades of the fifth century to accompany the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus is itself a striking addition to the image of the city.

While excavating the area around the houses of Augustus and Livia and the precincts of Magna Mater and Victoria on the Palatine, archaeologists found another set of terracottas. These were uncovered beneath and behind a structure identified as the Temple of Victoria Virgo, along with several walls in cappellaccio that pertain to a religious building accompanied by three favissae (ritual pits) filled with votives. On top of the walls, in what appears to be a layer of destruction, were three antefixes with the head of Juno Sospita that date to the early fifth century (figs. 102, 103). The remains of the foundations (just two perpendicular walls) are insufficient for reconstructing a full plan for the structure, and the exact dimensions of the building are difficult to gauge. Still, the thin walls composed of just a single row of ashlars have generally been compared to other modest temples, including the temples at S. Omobono, which measure 10.6 meters wide, and the temple at Ss. Stimmate in Velletri, which measures some thirteen square meters.5 The comparison seems appropriate, especially as larger contemporaneous structures at Pyrgi, Caere, Rome, and elsewhere tend to have foundation walls composed of ashlars that are several rows wide.

FIGURE 99

Revetments from a temple on the Capitoline Hill, first decades of the 5th century. Painted terracotta, fragment 26 × 18 cm. Antiquarium Comunale, inv. 20093.

FIGURE 100

Revetments from Satricum, Temple II, early 5th century. Painted terracotta, height 25 cm. Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia.

FIGURE 101

Revetments from Segni, Temple of Juno, early 5th century. Painted terracotta, height 25 cm. Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia.

FIGURE 102

Antefix of Juno Sospita from behind the Temple of “Victoria Virgo,” early 5th century. Painted terracotta, 21 × 22.5 cm. Palatine Antiquarium. Inv. 380945, 34343.

FIGURE 103

Excavated cappellaccio foundation behind the Temple of “Victoria Virgo.”

This single new, comparatively modest building on the southwest Palatine slope may not appear to add much to Rome’s image, but in the context of at least two other buildings that had recently gone up there (discussed in the previous chapter), it adds to an increasingly substantial sacred area on the promontory overlooking the Tiber and valley below, an area that had, at this point, witnessed continued construction of sacred architecture from at least the mid-sixth century through the early to mid-fifth. Moreover, during the same period or soon thereafter, a large stone platform was installed off the slope of the Palatine, below the later Temple of Victoria, perhaps as a site for augury (an auguratorium) or as a forecourt tied to the sacred building with antefixes of Juno Sospita.6 Further still, a wall of some kind, either a terracing wall or a temenos wall, was constructed concurrently around the corner of the hill, enclosing the new temple, the platform, and the other, earlier sacred buildings.7 In all, by the early to mid-fifth century, at least three moderately sized buildings adorned with sculpture stood on the promontory, two with a secure religious function alongside a large, raised stone forecourt and enclosure wall. Whether this area had been sacred from the earliest days when huts dotted the landscape or this character developed over time, by the early fifth century, it seems clear that a substantial sacred precinct capped this area of the Palatine. The space would remain among the most enduring holy sites in Rome through the Republic and Empire, when temples to Victoria and Magna Mater accompanied and supplanted those that already stood in the precinct.8 In fact, as the Palatine grew as a place of elite residences, it seems that nearly the entire hilltop became an elite domestic quarter, with the sole exception of this corner, where sacred rites stretched back through the Republic, finding their roots in the monuments of the late sixth and early fifth centuries, or perhaps even earlier.

Across the hill, over the entire northern slope from the Forum to the Colosseum valley, small but clear traces of continued activity and further monumentalization are extremely fragmentary, but telling nonetheless. Excavations around the newly built, monumental homes uncovered minor changes to the houses that now characterized the area. For the most part, evidence is of a few new interior walls and repaved floors, a drainage channel added in one area, and other minor refurbishments, but there was no wholesale repurposing on the scale seen in the late sixth century.9 Rather, the image is of refinement and continuity throughout the century.

At the opposite corner, close to the later Arch of Constantine, excavators have uncovered remains of a street and a wall in cappellaccio. The close proximity of the wall to earlier sacrificial remains suggests that a sacred precinct already in existence by the late seventh century gained more substantial architectural elaboration near the end of the archaic period. Recent excavation uncovered silen-head antefixes and other fragmentary examples of the same dancing maenads found in association with the Temple of Castor in the Forum, discussed later in this chapter.10 As with that site, the finds from the northeast Palatine, overlooking the Colosseum valley, date between 480 and 470. Sadly, at present, the remains reveal very little about the precise function, or even the overall image, of the buildings in the area. There seem to have been two sites, and excavators suggest that one may be an early iteration of the Curiae Veteres. Whatever its function, the remains indicate that a substantial building constructed in well-dressed stone and with a substantial terracotta roof stood at this corner of the Palatine Hill. Along with the second temple on the Capitoline and new sacred architecture on the southwest Palatine, the remains indicate that yet another monumental building was part of the early fifth-century cityscape. What is more, the existence of such a building at the edges of the Colosseum valley is yet another indication that, however much the Forum plain may have become a place of civic cohesion, the city was large, and it was undergoing monumentalization in several directions, including toward the Colosseum valley and overlooking the riverside, both from the Capitoline and Palatine hills.

FIGURE 104

Revetment with an anthemion relief from Velia, early 5th century. Painted terracotta, 25.5 × 33 cm. Antiquarium Comunale.

In fact, although proper excavation and finds from the Velia and Esquiline are rare, they too bear witness to the spread of impressive architecture in still more dispersed areas across those hills. On the Velia, the wells uncovered in rapid excavation during the 1930s of the soon-to-be demolished hill attest to wealthy inhabitants discarding the residue of elite life into pits surrounding their homes, and another pair of small finds from the excavations provides a glimpse of the kind of architecture that would have dotted the hill beginning in the early fifth century: namely, a floral revetment and, possibly, a column casing (fig. 104).11 Most scholars have suggested that the remains belong to a temple; again, so little of the structure survives that its plan and precise function remain in doubt, but the revetments are nonetheless a find worth consideration. Their relief decoration is composed of upright and hanging palmettes and lotuses, both open and closed, in an impressively intricate and delicate design. They are stylistically comparable to those from the Temple of Castor. In both, ribbons and volutes are used liberally to connect floral elements, and all decoration, including lotuses, palmettes, ribbons, fasteners, and volutes, have a bulbous quality with a rounded execution rather than the peaked or blocked relief found in similar revetments elsewhere in Central Italy. Paint is used liberally and especially in the interstitial areas to highlight the form and shape of the design. At twenty-five centimeters tall, and executed with exceptional detail, the interlaced anthemion design is comparable in size, style, and craftsmanship to several others from Pyrgi, Satricum, Rome, and Segni, all of which adorned truly monumental temples (see figs. 99–101).12 The composition of the Velia relief does not have as close a comparandum as does the revetment from the Capitoline, so the relative scale of the temple it adorned cannot be determined with such certainty. Still, anthemion revetments of this size are not found on temples smaller than the 18.5-square-meter Portonaccio Temple at Veii, and one should therefore expect that the revetment from the Velia would have adorned a temple of substantial size. It was certainly expertly crafted.

Further east, on the Esquiline, another isolated terracotta reveals more impressive architecture, but this time it is not the size of the building that is remarkable, it is the international character of its sculpture. During excavation of tombs in the Piazza Vittorio Emanuele II, Rodolfo Lanciani unearthed a two-thirds-life-size sculpture of an Amazon slain in battle (figs. 105, 106). The piece has long been regarded as a masterwork of archaic sculpture: a fallen Amazon lies on her right side, still holding her shield aloft; the wound below her left breast issues blood down her torso; and a broken piece of terracotta joining her right calf reveals that another figure, hypothetically reconstructed as her attacker, hovers over her, perhaps still driving a spear into his victim. In a recent analysis of the sculpture and its historiography, Patricia Lulof has pieced together its probable incorporation into a fill below the first-century Horti of Maecenas and suggests that it was originally an acroterion for a temple of the late sixth or very early fifth century.13

Scholars note that the painting and sculptural qualities of the statue are a tour de force and have long suggested that a Greek craftsperson was behind the execution. In a detailed analysis of the warrior, Lulof confirms that it was manufactured by a Sicilian artist.14 She notes that the sculptor created the body of the Amazon using three layers of clay: a thick underbody to generate the basic shape; a smoother, refined coating to give detail to the anatomy of the figure; and a fine slip on top for polychrome. The technique is absent in the Mediterranean except in South Italy and Sicily. Lulof adds, however, that only the torso of the figure is constructed with this technique, and a few parts of the Amazon are, instead, constructed using only one layer of clay; apart from the Roman Amazon, the combination of both techniques in terracotta sculpture is found only on Sicily. Moreover, in a study of contemporaneous architectural sculpture from around Rome, the Amazon is the only piece whose material is not terracotta made from a regional clay source. In fact, it is made of clay with inclusion of mudstone, which is not found elsewhere in Central Italy, but is common on Sicily.15 She concludes that a Sicilian sculptural master was commissioned by a patron in Rome to create this acroterial statue and probably a vast program for a precious temple on the Esquiline. In fact, as Lulof adds, the style of the sculpture and its polychrome are matched by particularly close examples from Sicily.16 Either the artisan brought his ceramic materials from Sicily or, far more likely, he created the group on the island, and the valued works were then shipped up to Rome. Examples of the long-distance transportation of whole roofs have been documented between Campania and Central Italy, and the Esquiline warrior would seem to reveal that roof sculpture was traveling even further, from Sicily to Rome.17

FIGURE 105

Amazon from the Esquiline, early 5th century. Painted terracotta, torso fragment 37 × 23 cm. Capitoline Museums, Rome, inv. 3363.

FIGURE 106

Reconstruction drawing by Patricia Lulof of the Amazon from the Esquiline

The sculpture is all that remains of the temple. Several scholars have suggested that another revetment of a procession, following the system used at S. Omobono, as well as a large ridge tile and part of a metal tripod may all belong to the same sanctuary, but the procession relief would not date later than ca. 540–510, and the fallen Amazon would not date before ca. 500 and would not belong to such an early roofing system. The finds would therefore appear to belong to two different temples. Scholars have suggested two possibilities: an aedes fortunae built by Servius Tullius, although that would be much too early for either piece, and a Temple of Spes, which ancient texts mention existed by ca. 477.18 The identification cannot be ascertained with confidence through the available remains, and it is not even clear that all the terracottas should be ascribed to sanctuaries on the Esquiline. Given that the Amazon was found in a secondary context, as part of a fill from the first century BCE, it and the revetments could in fact be from any part of the city. They could perhaps have come from one of the other hills, although it seems unlikely that workers would haul earth so far and uphill for an organized dump. In any case, these doubts do present problems in the assemblage of a precise image for the cityscape, and they are therefore truly unfortunate.

The Amazon is nonetheless extraordinarily important. It joins revetments from elsewhere in the city to reveal something of architectural decoration in archaic Rome. Alongside earlier examples from the roofs at S. Omobono and the Regia and the innovative architecture and revetments of the Temple of Jupiter, it is yet another example of Romans’ interests in international artistic trends and of their direct ties to foreign artists. Meanwhile, its value stands alongside the Hercules and Minerva, the more permanent and monumental architecture of the Regia and Comitium, and the expansive homes on the Palatine as yet another example of the rising luxury of art and architecture in the city, built with more lasting, sturdy, costly materials and more and more exotic decoration.

Just as parts of the Capitoline, Palatine, Velia, and Esquiline seem to have been devoted increasingly to monumental houses and religious buildings, the far eastern plateaus of the Esquiline and Quirinal also saw increased sumptuousness, but, for their part, the excess was lavished on graves. Archaic graves in Rome are scarce, largely because the outlying parts of the ancient city were covered over with architecture during Italian reunification in the late nineteenth century; no early monumental necropolis like those at Caere or Orvieto has yet been found in Rome, but this probably has more to do with the modern city than the ancient. Nearly every excavation on the northeastern Esquiline and Quirinal that has reached the lower levels of the city has uncovered graves. For most of the seventh and sixth centuries, the extant burials were small cremation and inhumation fossa graves (sometimes partially revetted in rough tuff slabs) with burial deposits of local character, including fibulae, small bronze figures, impasto vases, and, for exceptionally wealthy people, bronze pectorals, cistae, jewelry, and spears.19

The early fifth century brought a new formalization of space and a refinement of sarcophagi and cinerary urns that may indicate a change in Romans’ access to building materials from much farther afield. Excavations in the Piazza Vittorio Emanuele in the early twentieth century and again between 2003 and 2005 revealed over twenty sarcophagi constructed of finely carved rectangular slabs of peperino tuff.20 The burials were either plundered in antiquity or their remains were discovered and preserved (though now lost) in the early twentieth-century excavations; in either case, their original contents are currently a mystery. That does not mean the graves are not instructional. The very presence of so much peperino used for tombs in Rome is revealing. The material is only available in the Alban Hills, and the concerted effort to line tombs in a fine, hard stone, which had to be transported over land into Rome, reflects a capacity to devote time and resources to sumptuousness rather than utility, even in objects that would vanish from sight after only a few days of use. It also reveals a certain access to distant building materials. Textual sources suggest that by the early fifth century, Rome had a hold on the nearby Alban territories, variously by treaty and by conquest.21 Archaeological remains have not been able to confirm the traditional history absolutely, but the abundance of these sarcophagi would seem to indicate that Romans either had some kind of influence in the hills or that the political circumstances in Latium allowed them access to materials far outside of their city’s periphery and into the territory of other polities.

Alongside these early fifth-century peperino sarcophagi was another burial, where the deceased’s remains were placed in a rectangular cinerary urn with a pitched cover. This urn was in turn placed in a larger, finely carved peperino chest. The chest itself is yet another example of Romans getting their hands on material from the Alban Hills, but it is often overlooked for its exceptional contents. The smaller urn inside it, measuring sixty-one by thirty-eight by thirty-two centimeters, is a finely carved and sumptuously painted chest of Parian marble (fig. 107). It is the only known example of marble from the Aegean island used in such a capacity in the entirety of Central Italy, save a fragment from a similar chest at Caere.22 The presence at Rome of such a lavish burial object, matched only at one of Central Italy’s greatest cities, speaks of significant ties to the outside world. In fact, the only known comparanda for the object elsewhere in the entire western Mediterranean come from Spina in northeast Italy and from Cumae in the Bay of Naples, and their remarkable similarity leads scholars to suggest that either they all come from the same Parian workshop, or that a single craftsperson was importing the marble to Italy to create exceptional, elite burial paraphernalia.

FIGURE 107

Cinerary urn from the Esquiline, early 5th century. Painted white (Parian?) marble, 61 × 38 × 32 cm. Museo Centrale Montemartini, Rome. Antiquarium Comunale, inv. 455.

Unfortunately, little more can be said of burials from the period, and without contents from the graves, it is hard to say more about the community of the dead in early fifth-century Rome. Still, the increased expense lavished on the urn and sarcophagi represents an elevation in excess wealth in Rome. This occurred just as the rest of the hilltops reveal more sumptuous architecture, and it will become clear that the same display of wealth is found in other areas of the city. In this context, the character of the burials is doubly revealing: nearly every fifth-century burial that has been excavated has given up the peperino sarcophagi, and their quantity suggests that refined, imported, expertly quarried stone was not the exclusive right of a very few, but rather of a wider set of the elite population.23 Romans were either wealthy enough to import the material routinely, or their control of Latium was substantial enough to allow them to demand it. In either case, their orbit was growing, and the polity’s reach seems to have touched a wider population. Meanwhile, the marble urn reveals that some of Rome’s elite were capable of importing lavish materials from halfway across the Mediterranean. Compared to marble funerary stelae and statues in the east, it is small, but that hardly makes this urn less impressive. The exoticness of the material carried a more powerful message in Central Italy, far from its source.24 Moreover, this urn was to be enclosed and buried. That is to say, while the stelae would remain aboveground and had a much more enduring visual impact, the deceased in Rome lavished the expense on a funerary object that would disappear after it was interred. This truly speaks to a culture of prestige and excess in Rome in the early fifth century. It is unfortunate that so few graves from the period have been uncovered, but it is nonetheless striking that the vast majority of the few that have been excavated hint at a culture of resource and demonstrate yet again an interest in luxury goods from afar.

Overall, though impressive, the image of the hilltops in the period is sadly fragmentary. On the Palatine, the southwest and north slopes are all that have seen real excavation; 90 percent of the surface remains buried beneath later architecture. The same is true of the Capitoline, where real excavation has only happened at the Temple of Jupiter (see fig. 1). The Velia, now largely demolished, and the Esquiline, Quirinal, Caelian, and Aventine, all buried beneath modern construction, have only seen sparse scientific excavation down to archaic levels. Still, it is important to recognize that nearly every investigation that has touched the late sixth and early fifth-century layers of the hilltops has turned up substantial remains of architecture or burial. Even on the Caelian, a rare sounding that reached down to archaic levels discovered a rubble wall, perhaps for a house, dating to the late sixth century.25 In short, one should not see the lacunae in maps of the archaic hilltops as an indication of a lack of buildings or burials, but rather as a lack of excavation. With so much monumental architecture in the city, and with the desire for so many sanctuaries and so much civic infrastructure (as is discussed in the following sections), one should in fact expect that the surface of the Palatine and Capitoline, most of the western Esquiline and Quirinal, and perhaps even the Caelian and Aventine were filled with domestic and civic buildings to house the people of Rome and their institutions.26

What does remain on the hilltops is an impressive and widespread image of luxury, monumentality, and wealth in every genre of architecture. On the hills alone, two impressive temples on the Capitoline, another on the Velia, and a packed sanctuary on the southwest slope of the Palatine with at least three sacred buildings all stood along with the great houses of the north slope, another sanctuary by the Colosseum valley, and yet another sacred building manifest in a masterful archaic sculpture of an Amazon slain in battle. Together, these finds reveal that in every corner of the city there were impressive monuments, growing swiftly in number and proclaiming from the city’s highest points the power and influence of the people of Rome.

According to historical tradition, between 499 and 496, Romans fought rebellious Latins at the battle of Lake Regillus, where Aulus Postumius prayed for the aid of Castor and Pollux, in whose name he vowed a temple, should he win. Soon after the victory, the Dioscouri appeared at the site of the Lacus Iuturnae by the Atrium Vestae to water their horses and proclaim Rome’s victory.27 In recognition of his promise to the Dioscouri, Postumius purportedly founded a temple just across from the site of their epiphany, in accordance with his vow. The inclusion of the two demigods in the events may be legend, but recent excavations have borne out at least the basic framework of the temple’s foundation story. On the very site that ancient sources describe, just by the Lacus Iuturnae, excavators have unearthed terracottas and substantial foundation walls for a monumental Temple of Castor and Pollux dating to the early fifth century, concurrent with Livy’s account of a dedication in 484.28 The temple is just one of several major changes that swept the Forum plain around the turn of the sixth to fifth centuries. Just prior to its construction were the overhauls at the Comitium, Regia, and Atrium Vestae, and along with the new temple to the Dioscouri, Romans began an initiative to pave the entire plaza in stone and, it seems, to build a second temple at the base of the Capitoline, dedicated to Saturn.

FIGURE 108

Schematic plan of the foundations of the archaic Temple of Castor: following Nielsen and Poulsen 1992, pl. 12.1.

FIGURE 109

Plan of the archaic Temple of Castor: following Nielsen and Poulsen 1992, fig. 55.

On the site of the Temple of Castor and Pollux itself, excavations have revealed a truly monumental building, some 27.5 by 37 to 40 meters. Once completed, it became the third-largest and most extensively decorated temple known from all of archaic Central Italy, surpassed only by the Temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline and the Ara della Regina at Tarquinii (figs. 108–110). Its footprint is just a few meters smaller than that of the Augustan iteration of the temple, whose podium still dominates the plain today. What is more, excavation down to the archaic ground level and within the subterranean foundations uncovered remnants of a tall stone foundation and podium, towering five meters above the Forum plain, just as the Imperial temple did.29 The podium lies at the southern corner of the Forum, where the ground of the Palatine Hill slopes sharply down to meet the flat ground level of the reclaimed Forum basin, and the temple is oriented to the northeast, facing across the open Forum.30 The foundations and podium are formed of intersecting walls, similar to those in the Temple of Jupiter. Builders laid slightly wider foundation courses in the ground to support the high podium walls in the area of the cellae and a solid foundation at the front, beneath the colonnades; also, as with the Temple of Jupiter, they filled the spaces between the walls with earth and then capped the podium with twenty-centimeter-thick slabs of cappellaccio to create the temple floor.31

FIGURE 110

3-D reconstruction of the archaic Temple of Castor, view from the north.

Above the podium, the design of the building remains somewhat unclear, but archaeologists are able to reconstruct an approximate plan based on the grid of foundations. These suggest a triple-cella temple with three colonnades occupying a deep porch.32 Given the size and weight of the roof, sheathed in terracottas, excavators conclude the walls and columns of the building, whatever their configuration, must have been fully rendered in stone. Like the Temple of Jupiter and most moderate to large temples in Central Italy, stone was critical for a lasting building capped with such a weighty roof, and with spans of ten meters, the Temple of Castor would also require a complex and expertly crafted roof. Terracotta fragments of revetments, simas, antefixes, and openwork crestings from the roof and stucco from the temple walls reveal a rich ornamentation.33 The revetments were adorned with a strigil course atop an anthemion decoration in relief, and simas with a strigil course atop a painted guilloche band; they are similar in style and coloring to the revetments of the earlier Temple of Jupiter as well as contemporaneous temples at Veii (Portonaccio), Pyrgi (A), Falerii Veteres (Sassi Caduti), Satricum (Temple II), and the second temple on the Capitoline in Rome. By contrast, the antefixes show a relatively new style. Until the early fifth century, figured-head antefixes dominated Central Italy, but the Temple of Castor’s are large, intricate, full-bodied silens and maenads like those on the contemporaneous early fifth-century temple at Satricum.34 In all, the terracottas covering the roof and the stuccoed, painted walls of the temple reveal a rich and complex program of decoration adoring a monumental, lavish temple.

Outside of the Temple of Jupiter and Ara della Regina, the only known temple in Central Italy that can match the length of the Temple of Castor is the one dedicated to Juno at Segni, but that temple is not as wide. The next-largest is Pyrgi, Temple A, but although substantial at 24 by 34.5 square meters, its footprint is 828 square meters, compared to the Temple of Castor, which is between 1,018 and 1,100 square meters: some 19 to 25 percent larger. This does not even account for the towering podium of the Roman temple, which is five times as tall as its closest rivals at Pyrgi, Segni, Ardea, and elsewhere. In the end, as a colonnaded stone temple over twenty-seven meters wide and nearly forty meters long raised on such a tall podium, the grandeur of the Temple of Castor considerably surpasses all but the two greatest temples of Central Italy.35

Like them, its overwhelming impression is better understood in comparison with the famous archaic and classical temples at Olympia, Selinunte, Agrigento, Syracuse, Corinth, and elsewhere. Among the Temple of Hera at Olympia, the Temple of Aphaia at Aigina, temples C, D, and F at Selinunte, the temples of Concordia, Hera, and Herakles at Agrigento, the Temple of Apollo and the Ionic Temple at Syracuse, and the Temple of Apollo at Corinth, none has a facade as wide as that of the Temple of Castor in Rome (fig. 111).36 Of course, each of these temples had a length-to-width ratio that made it more elongated. Still, the Roman temple covered more square footage than the temples of Hera at Olympia and of Concordia, Castor and Pollux, and Hera at Agrigento—all famous for their imposing stature—and it covered 95 percent of the footprints of the temples of Artemis at Corfu and Apollo at Corinth. What is more, the Roman temple towered above devotees on a foundation and podium that raised it five times higher than the stylobates at Agrigento, Corfu, Selinunte, Corinth, Olympia, and elsewhere. It was a remarkable building for any city in the archaic Mediterranean, and it fit well in the growing urban image of Rome, with its increasing number of impressive temples.

Given the corroboration of the textual tradition in archaeological finds and the continued use of the building and its refurbishment through the Empire, there is little doubt that this temple served the cult of the Castores from its creation in the early fifth century.37 With this in mind, one must question what it says that such a rare monumental temple at the heart of a Central Italic city would host this particular cult. Worship of the two demigods is attested in Central Italy—Latium especially—for over a century prior to this building, so to some degree, the cult is not new.38 But there is no evidence of a sanctuary or ritual hub dedicated to them that is remotely as impressive, and throughout its history, this sanctuary remained if not the most impressive site dedicated to them in the region, then certainly one of the top two: the other being at Tusculum.39 In fact, because the inauguration of the temple is so closely tied to conquest in Latium, and because of the particularly close association of the demigods with Lavinium and Tusculum in Latium, most see the Roman cult as stemming from the Latin character of the demigods, which time and again has shown a deep connection to rituals from Sparta and South Italy, in contrast to the character of the demigods in Etruria.40 At the same time, given that the temple was inaugurated at the center of the city (and presumably within any sacred bounds, including the pomerium), some have suggested that this must be evidence of the existence of the cult in Rome prior to this temple.41 Livy says that the vow was for a temple, not to inaugurate a new cult of Castor and Pollux, so the cult space may have existed at Rome for some time. This would make sense; evidence for buildings below the Temple of Castor may be testimony of earlier cult activity, in which case the temple would not be a sign of Romans appropriating a cult from outside their city in something similar to (though not the same as) evocatio, but rather a sign of them aggrandizing their own cult center in such a way as to supersede those of their vanquished Latin opponents.42 The purpose of the earlier buildings remains unclear for now, though, so this remains speculative.

FIGURE 111

Scale comparison of the temples of Apollo at Corinth, Hera at Olympia, Artemis at Corfu, Aphaia at Aigina, and Castor at Rome, from left to right.

In any case, the temple gave new prominence to the Castores in Rome and new prominence to the Roman cult of the Castores in Latium and all of Central Italy, and this is truly significant. Just a few decades prior, Romans had established on the Capitoline a sanctuary for Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva—a temple to the head of a religious pantheon along with his wife and daughter—on the highest point of their city.43 In doing so, they created a cult center, whose religious meaning as a home of the “best and greatest” of gods and whose visual impression as one of the largest temples built in the whole of the archaic Mediterranean established Rome as a primary (perhaps the primary) center for religious dedication in Central Italy. The presence of this truly monumental sanctuary to the Castores at the heart of Rome adds to that image. It would remain among the most opulent sanctuaries in the region for centuries and was a chief place of worship for the gods thereafter. In this sense, the monumentality of these two sanctuaries at the heart of Rome indicates that there was something more about the urban environment than just large, sumptuous construction. Romans were raising more and more—and ever more diverse—cults in their city, effectively establishing themselves as a religious center as much as an architectural or economic one, and these temples were not alone. As seen on the hilltops, and as will be seen elsewhere in the valleys, as the years passed, they continued to add to this visual and physical impression of religious imperative.

There has been only one substantial excavation in the area immediately northwest of the Temple of Castor, below the later Basilica Julia. In that small sounding, there were several archaic and early Republican layers, but only fragments of a few walls and terracottas that date with certainty to the sixth or early fifth century. In a small sounding within the trench, excavators uncovered several strata containing ashlar blocks and antefixes of a silen’s head and of Juno Sospita, which date to the early fifth century.44 The ashlars are distinct from those discussed previously in regard to a potential reclamation embankment wall and are slightly higher in elevation; the antefixes have been linked to the Temple of Castor.45 It is difficult to make any claims based off such unclear, fragmentary finds, but the ashlars indicate that another building stood along the edge of the Forum fill, hard by the Temple of Castor, by the beginning of the fifth century. For now, its form and function remain unclear.

Across the plain, at the base of the Capitoline Hill, textual sources also mention the construction of a Temple of Saturn in the early fifth century. Sadly, these sources do not describe its size, plan, or decoration. Macrobius says that the sacred area had existed for some time, back to the age of Tullus Hostilius; according to Macrobius and Dionysius, initial construction of the temple building began either with the kings or the first consuls, and it was dedicated between 501 and 493. The next mention in ancient texts of refurbishment or reconstruction of the building is with L. Munatius Plancus’s restoration of it in 42 BCE.46 As with the Temple of Castor, archaeological remains can corroborate little of the tale surrounding the creation of the first Temple of Saturn with real certainty, but they do suggest that it was in fact completed in the early decades of the fifth century. The interpretation here is a bit more complicated, though, than it is in the case of the straightforward archaeological finds from the Temple of Castor.

FIGURE 112

Foundation plan of the Temple of Saturn, with remains in black and probable walls in dashed lines: following Maetzke 1991, with modifications.

As with that excavation, archaeologists have found early foundations beneath the late Republican Temple of Saturn, this time three parallel walls (fig. 112). In overall form, they resemble the longitudinal foundations of the Temple of Jupiter and Temple of Castor, and the material in the Saturn foundations is the same gray granular tuff (cappellaccio) used in the foundations of the other two temples; furthermore, at two and a half meters wide, the walls are the same width as the foundation walls in the Temple of Castor and are constructed similarly, with two headers and one stretcher laid in rows across each course.47 The repeated correspondences may suggest a fifth-century temple, but excavations at the Temple of Saturn did not uncover the same stratigraphically sound, datable ceramic material that the Temple of Castor and Temple of Jupiter excavations did. In fact, they were originally uncovered during unscientific excavations in the eighteenth century and are entirely without stratigraphy or any securely datable finds. Furthermore, the individual tuff blocks are about forty by sixty by ninety centimeters—roughly ten centimeters thicker than the Capitoline and Castor blocks—and this has created some doubt.48 Still, although this does indicate a departure from those two buildings, the dimensions are by no means proof against an archaic date. Sixth- and fifth-century cappellaccio foundations and walls elsewhere, especially in cisterns on the Palatine and at the temples at S. Omobono, vary in size, and many are as tall as forty centimeters, others as short as twenty centimeters. Dating based on ashlar dimensions is a notoriously problematic method. In sum, the material remains of the Temple of Saturn are ambiguous, and short of revealing that there was an early-Republican Era temple, they do not secure a date for the first Temple of Saturn.

Yet there is good reason to believe that the foundation walls do date to the early fifth century. Textual sources are unwavering, and as was seen in the case of the Temple of Jupiter, more and more scholars recognize these sources’ value in establishing dates for works of architecture (especially sacred buildings) that endured down to the late Republic and Empire. As Nicholas Purcell has noted, “Historical consciousness at Rome was linked with buildings and cults more solidly than with notions of constitutional change, important though that ingredient became.”49 Even scholars who distrust textual sources for early Roman political and military history tend to agree that literary evidence for the foundation dates of civic buildings—particularly sanctuaries and temples, with their annual sacred rights, priestly records, and dedications—gains some trustworthiness beginning with the “Capitoline Era.”50 From the dedication of the Temple of Jupiter onward, Romans used stone masonry more widely for foundations and superstructures in major temples, and these durable materials allowed the buildings to endure for centuries. The temples were also outfitted with votives, inscriptions, and institutions that bore tangible—and sometimes legible—objects documenting a history of existence. That is to say, monumental stone sanctuaries and their concomitant votives, traditions, and decorations stood the test of time. Like the Temple of Castor and the Temple of Jupiter, whose textual chronology have both been upheld by recent excavation, the Temple of Saturn stood for centuries; a record of activity specific to the building and its sacred functions would have supplemented any citywide annals and oral tradition to help chroniclers ascertain its origins with far greater accuracy than the passing speeches, events, and ephemeral artwork of the same period. Thus, its origins are far less likely to suffer fabrication.

Moreover, the Temple of Saturn was not just any temple; it contained the aerarium populi Romani (or Saturni)—the treasury of Rome—and the records associated with the security and distribution of state funds would leave a substantial trail of information on the building, which would allow historians to trace its roots. Further still, this is not just a case of possibility. In every way, the archaeology matches the textual tradition. The overall measurements and construction technique of the foundation walls are in complete accord with other buildings from the period, especially the Temple of Castor, and excavation of the site has found no intervention in the building until the construction of a towering concrete podium in the late first century BCE.51 This precisely matches the chronology found in Livy, Dionysius, Macrobius, Suetonius, and the epigraphic record, all of which state clearly that a temple was dedicated in the early fifth century and was only replaced in the late first century.52 If the Imperial temple stood today without any trace of a previous building, its fifth-century origins might be called into question. But this is not the case, and in the face of such accord between architectonic, textual, archaeological, and epigraphic records, a date corresponding to the textual tradition is most likely.

Whatever the precise years of construction, remains at the site indicate a hexastyle temple with a slightly expanded central intercolumniation, and an overall width measuring close to twenty meters.53 It was over two-thirds the width of the Temple of Castor (about twenty-seven meters), and one can imagine it suitably balanced its near twin at the south end of the Forum. Both faced onto the open plain, bordering the Vicus Iugarius and Vicus Tuscus, the two major arteries from the Tiber to the monumental city center.

With these two temples, the Forum seems in part to have acquired its lasting image. The Comitium, with its raised platform, cippus, and paved communal space at one end, would be the established seat of the Roman Senate and People until its demolition by Caesar half a millennium later. At the other end, the Regia and Atrium Vestae complex now featured more permanent stone buildings in a form that lasted for almost a millennium, and two temples joined them, adding further, enduring monumental religious character to the space.

To accompany these changes, beginning around 530, when the monumental houses went up on the north slope of the Palatine, Romans had begun to pave roadways entering the Forum in stone. A second stone street joined the “Via Sacra” in the early fifth century, leading from the Forum to the riverside, by the Temple of Castor. It became known as the Vicus Tuscus, as it purportedly led through a quarter of the city with an Etruscan character.54 At the same time, in the early fifth century, to connect these new roads and the buildings surrounding the Forum plain, it seems that Romans paved the entire space in flags of cappellaccio stone. Excavators of the Temple of Castor found traces of the pavement surrounding the temple and dating contemporaneously with its construction, and archaeologists also identified it in excavations at the later Lacus Iuturnae, Arch of Augustus, and all around the Temple of Caesar (fig. 113).55 At the center of the plain, too, in excavation at the “Equus Domitiani,” Gjerstad identified further evidence for cappellaccio flags of the same dimensions dating to the same period as the remains in the southern half of the Forum (fig. 114).56

FIGURE 113

Elevations (in meters above sea level) of archaic cappellaccio flags (pavement 1) in the following areas, in relation to the elevation of the Temple of Castor: A) Temple of Caesar; B) Lacus Iuturnae; C) Temple of Castor, trench A; D) top of the podium of the Temple of Castor; E) archaic Vicus Tuscus; F) Basilica Julia; and G) Equus Domitiani: following Nielsen 1990, fig. 6.

FIGURE 114

Equus Domitiani excavation, with cappellaccio pavement at the left edge.

As with so much of the cityscape, it is difficult to assemble a full image of the central plain and to determine if, indeed, the stone floor covered the whole space. Yet it is hard to dismiss the finds. In every excavation down to the early fifth-century levels, these same stone pavers have turned up. To be sure the plaza was flagged entirely, further widespread excavation will be necessary. Still, at present, the evidence points in that direction, and the preponderance of cut stone in massive quantities used in architecture and infrastructure throughout the city suggests that Romans were moving toward this kind of durability in all manner of construction, and that the Forum plain may itself have seen its first full pavement in hard, sturdy material at the start of the sixth century. One need only consider the difference between dragging a cart on gravel and on stone, on earthen (sometimes muddy) streets and on those flagged in smooth ashlars, to comprehend how transformative this action was. Alongside the monumentalized stone civic and sacred buildings that now opened up onto the plain, the stone pavement would give prominence and polish to an area that seems to have become—and would remain for a millennium—the heart of the city and, eventually, the empire.

Down by the riverside, the small temple at S. Omobono fell sometime around 500 and left the site in need of a new temple. Scholars are divided on the date of the next phase of construction, which transformed the sanctuary’s image. Some argue for reconstruction within the next few decades, while others contend that the site lay barren until Marcus Furius Camillus’s purported reconstruction, which textual sources date to 396.57 Those texts do not indicate that the site was in disuse for the intervening century; rather, the suggestion of abandonment stems entirely from the modern interpretation.

During initial excavations, archaeologists unearthed a massive platform composed of a stone perimeter wall that had been filled with earth and debris (fig. 115).58 Within the wall, embedded in the fill and pertaining to the perimeter structure, were deep foundation walls and pillars that supported the columns and walls of two monumental temples, which stood atop the platform; they occupied its rear, and before them lay a vast, open forecourt (fig. 116). Further excavation laid bare the entire height of several parts of the perimeter wall and of a pillar that supported one of the temple’s columns. The pillar and walls are composed of ten courses of cappellaccio, and exploration in 1974 revealed more of the east perimeter wall and also allowed a stratigraphic study of its foundation trench.59 The trench cuts a terracotta deposit and leveling layer above the destroyed second temple and indicates that builders dug through those activities to lay the perimeter wall. The platform therefore undoubtedly postdates those activities.

FIGURE 115

3-D reconstruction of the foundations of the twin temples at S. Omobono, axonometric view.

FIGURE 116

Plan of the twin temples at S. Omobono.

Those who believe the platform belongs in the fourth century—some one hundred years after the destruction of the second temple—argue that, in accordance with practices in use from the sixth through the third centuries, builders used cappellaccio for the foundation walls and pillars and the perimeter walls, but these scholars point out that the foundations and the fill were then covered over in a pavement of Monteverde slabs, many of which remain on the site.60 Monteverde is not used in Roman construction until the early fourth century, so it would seem that the cappellaccio foundations and the accompanying Monteverde pavement must date no earlier than ca. 400. This fits remarkably well with the tale of Camillus and his purported refurbishment of the twin temples at the site. The premise is clear and it would be compelling, except that there is no stratigraphic or architectonic reason to tie the Monteverde slabs to the same activity as the cappellaccio foundation. The blocks of Monteverde tuff are only used as a pavement, placed atop the cappellaccio foundations. They could easily be part of a later repaving of the sanctuary, perhaps Camillus’s famed renovation. Such repaving is common throughout the city in the Republic and Empire, and in fact, the twin temples at S. Omobono themselves exhibit several later repavings, with stone laid directly on top of earlier floors.

What is more, there is evidence of a pavement of the podium that predates the first Monteverde pavement. Antonio Maria Colini notes two pavements in Monteverde tuff at the west side of the platform. Scholars largely agree that the second (upper pavement) dates to a reconstruction of the area ca. 213, and that the first (lower pavement) dates to Camillus’s building.61 In excavations in front of the apse of the church in the eastern portion of the platform, Gjerstad states that he too uncovered evidence for two pavements. His top pavement is in Monteverde stones on a thin, beaten-earth stratum. The bottom pavement is evidenced only by a distinct layer of beaten earth; it is identical to other such layers found throughout the city where pavement slabs were removed in antiquity. In the eastern portion of the site, where Gjerstad was excavating, the second (upper) Monteverde pavement is absent; there, only the first (lower) Monteverde remained in situ past antiquity.62 Thus, Gjerstad’s Monteverde pavement corresponds to the earliest pavement and reconstruction, and the other below it appears to be a still earlier pavement that would correspond to a phase of construction before ca. 396. Recent examination of unpublished excavation material by teams currently excavating the site as well as finds from new soundings reveal more of the compressed earth foundation for an early fifth-century cappellaccio pavement, upholding this interpretation.63

In addition to the pre-Monteverde (pre-396) pavement, there is further reason to believe that the monumental double sanctuary was built in the early fifth century. As Colini notes, evidence is clear (and scholars agree) that the second temple fell around 500. If the temples were only rebuilt under Camillus, that would mean the site lay in utter abandon for over a century.64 It is hard to believe that Romans would leave so historic and prominent a religious site empty for that long. Although this is not sure proof of a rebuilding ca. 500, it should arouse some doubt about arguments for a late reconstruction. Moreover, suspicion only increases upon examination of the stratigraphy of the site, which offers a further, positive means of establishing an early date. Atop the destruction and leveling layers that cover the second temple, builders deposited an enormous amount of earth and debris to fill the inside of the platform and raise the area around it; in analyses of this fill, archaeologists have discovered not one find dating to the fifth century or later.65 Enrico Paribeni and Giovanni Colonna published finds from the 1938 excavations and record nothing that dates after ca. 500. In subsequent excavations, archaeologists concluded that of the hundreds of Euboean, Pithecusan, Corinthian, Ionic, Attic, and Italic impasto and bucchero in all of the strata—from the destruction of the second temple to the ceremonial deposit above it, the leveling layer above that, and up to the top of the fill of the twin temple platform—not one fragment dates after the end of the sixth century.66 Recent and ongoing investigations of previous excavations as well as new soundings have found the same situation, with materials deposited in layers of both fill and the foundation trenches for walls and pillars of the twin temples dating no later than the end of the sixth century.67 If, in the face of Colini’s argument, one were to suggest that Romans could have abandoned the site for a century, one must still contend with the absence of fifth-century materials in the fill of the cappellaccio podium and all layers below it. It is hard to imagine that over the course of more than one hundred years of urban development and occupation all around it, and in the process of dumping vast amounts of earth and debris within the platform, not one scrap of material culture from after ca. 500 would find its way into the site, or that after abandonment, for a century no trace of activity would appear in the stratigraphy or construction of a temple built in the fourth.

All evidence points to an early fifth-century reconstruction, and a small stash of terracottas from the excavations of 1938 may settle the argument. In all, only three revetment plaques and two roof tiles have been published. The roof tiles are undecorated and do not offer substantial chronological clues.68 The revetments, on the other hand, offer a firm date (fig. 117). The remaining fragments are part of a large anthemion relief. One piece contains a five-frond palmette held at its base by two volutes banded together; the volutes are each part of long, S-shaped spirals. An undecorated band circumscribes the palmette, and on this fragment the band also defines the lower edge of the plaque. Another fragment retains the other end of the S-shaped spiral, where it connects with another volute. As Gjerstad points out, these fragments are identical to a set of reliefs that adorned the Acropolis Temple at Ardea, and a comparison with the Ardea plaques allows a full image of the revetments at Rome.69 They constitute a two-tiered anthemion decoration; the top palmettes are upright and fastened at the bottom to S-shaped spirals, which curve down and lock together to hold the lower palmettes, which are themselves upside down. A thin band weaves between the palmettes, and a torus and strigil course top the relief. Arvid Andrén establishes a date for the Ardean plaques in the early fifth century, based on the style of both the palmette and strigil as well as the delicately outlined forms of the relief. Similarities are clear in the elongated, animated leaves of the palmettes from other early to mid-fifth-century anthemion reliefs at Satricum and Rome, as well as in the design of interlocking S-shaped spirals at Segni.70

FIGURE 117

Drawing of the double anthemion revetment used at Rome and Ardea, with Roman fragments, early 5th century. Painted terracotta. Fragments, Antiquarium Comunale, Rome. Inv. 15835, 15850.

The context of the S. Omobono terracottas is unclear, and there can be no illusion that their stratigraphy reveals more about their association with the twin platform. Yet their discovery at the site is striking. Along with the absence of finds dating after ca. 500 in layers pertaining to the construction of the platform, and the presence of a pavement predating a restoration of ca. 400, the early fifth-century revetments appear to confirm that soon after the small temple fell, Romans leveled the area around S. Omobono and built an enormous cappellaccio platform. Ongoing excavation continues to provide more and more proof of this and suggests that they quickly rebuilt and paved the platform, probably in cappellaccio, and over the course of the coming decades, they built two large, twin temples capped with terracotta roofs sporting a novel style of double-anthemion reliefs.71

In the new twin sanctuary, builders circumvented any major concerns about flooding: the top of the new platform was approximately 12.75 meters above sea level, some three meters above annual flood levels.72 Also, in contrast with the first and second temples, which are oriented north–northeast to south–southwest, the twin temples are oriented directly north–south. This created a massive shelf off the southwest corner of the Capitoline Hill, with its rear and eastern side only a few courses deep, but its front projecting five meters above the natural ground level. Thus, on all sides, and especially at the front, the temples and their platform loomed high above the surrounding area. Even in the Empire, the Vicus Iugarius was lower than the rear of the temple platform, and remains of an Imperial spur of the street flanking the north side of the sanctuary descend from a meter below the platform at the rear to nearly two meters below it at the front. A similar situation existed around the late fifth-century Temple of Apollo Medicus in the Campus Martius and the fourth-century Temple of Portunus, each just a few hundred meters from the S. Omobono platform. For these sanctuaries, builders also raised platforms nearly five meters off the ground with a temple on top.73 Thus, with the twin temples and their successors nearby, it seems that Romans building in the low-lying areas around the worrisome Tiber had decided to take more serious precautions when building monumental architecture.

As to the plan and elevation, like any temple that is missing much of the superstructure, a full reconstruction is necessarily hypothetical. Still, a conspicuous correspondence between the cappellaccio foundations of the archaic buildings and the extant late Republican and Imperial reconstructions remaining on the site provides substantial corroboration of the basic image (fig. 118). The Imperial remains reveal two temples at the north end of the platform with their backs to the Capitoline; they flank a central, longitudinal passageway that leads from the Vicus Iugarius to a forecourt at the front of the temples. The rear wall of the platform supports the rear walls of the two temples. The west colonnade of the west temple and the east colonnade of the east temple are on top of the longitudinal perimeter walls of the platform, and the opposing colonnades of each temple are on two longitudinal foundations that flank the central passageway. The cellae rest on deep cappellaccio walls, and in front of the cellae’s side walls, four foundation pillars support four columns, creating a dipteral facade. In front of the temple buildings, a wide platform paved in cappellaccio creates an open space slightly lower than the temples themselves. A stair of some kind mediated the change in elevation; whether it went across the whole width of the temples or only between the center columns is unclear. Scholars contend that the Imperial superstructure would correspond precisely with that of the original twin temples. This seems clear for the cellae and columns in front of them, but the character of the alae is debatable. It is possible that they were originally solid walls instead of colonnades.

Whatever the precise image of the colonnades, the platform measures 47.5 meters square, and each temple is 20.5 meters wide and 29.5 meters long.74 Elevated together, high above a viewer, the twin buildings created a truly overwhelming sight for visitors entering Rome from the Tiber. Individually, each has impressive dimensions, comparable to truly monumental temples, including the temples of Juno, Castor and Pollux, and Concordia at Agrigento, Temple B at Pyrgi, Temple II at Satricum, and Temple A at Selinunte.75 Yet the height and isolation of the platform above the surrounding area of the Velabrum, Campus Martius, and Tiber banks would join the double superstructures in a viewer’s eye. Towering five meters high above an approaching visitor, the double-temple complex was nearly fifty meters wide, as expansive as the Temple of Apollo at Didyma or the partially built Olympieion in Athens, and eclipsed in the Italic Peninsula only by the width of the Temple of Jupiter, which loomed high overhead. Perched as they were over the valley and river below, both colossal sanctuaries—atop the Capitoline and projecting off its slope—stood prominently over the banks of the Tiber. Facing south toward ships advancing to Rome, they formed an imposing, colossal facade for a truly impressive urban landscape.

FIGURE 118

3-D hypothetical reconstruction of the twin temples at S. Omobono.