Quantitative Verse

Classical Latin

B. Elements of the Line: Foot and Metron, Caesura and Diaeresis, Word Accent and Verse Accent

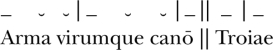

Classical Greek and Latin verse is quantitative, that is, it is dominated by and organized according to distinctions between long and short syllables. A Latin dactylic hexameter is a line of six dactyls or their equivalent. Analyzed according to feet, it can be represented in the following scheme, whereby each foot consists of a long syllable followed by two short syllables (the symbol > is conventionally used to indicate a terminal syllable that can be either long or short):

![]()

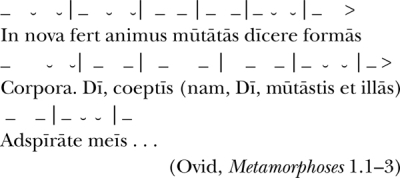

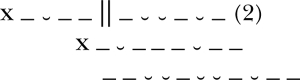

A common form of the hendecasyllable (an eleven-syllable line) might be represented as follows (the double vertical line represents a conventional word break):

![]()

The word we use to describe such analysis is scansion.

This chapter begins with the most common verse types and moves through more complex forms. With the detail provided here, even non-Latinists should be able to scan and imitate the epic forms (sec. D) and many of the lyric forms (sec. E). Further examples of verse types are given in the appendix. The scansion of iambic and trochaic forms, especially their dramatic varieties, poses far more difficulties (secs. F and G); my discussion of these forms is thus less detailed, since it would be unreasonable if not cruel to expect anyone other than a skilled Latinist to be able to scan, say, an extended passage from Terence.

A.1. Rules for Determining Syllable Length

Syllables in Latin verse are analyzed as long or short. A syllable is considered long in the following cases:

a) The syllable contains a naturally long vowel.

Note: Latin vowels are distinguished linguistically as long or short. These differences would be obvious to native speakers and vowel length is marked in modern dictionaries. Some naturally long vowels can be determined by rule: e.g., final -o or -i are nearly always long. Vowel length is not represented graphically in written or printed Latin (in Greek, the difference between, say, long and short -o- is represented as a difference between an omicron and an omega). For non-Latinists, it is convenient to find texts where editors have marked naturally long vowels. Introductory Latin books generally do this, as do many student texts printed in the early twentieth century; most standard editions, however, do not, even those designed for students.

b) The syllable contains a diphthong, that is, a monosyllabic vowel sound expressed graphically as two vowels. Examples: -oi- and -ae in the two-syllable word Troiae.

Note: Most double vowel combinations in Latin are not diphthongs. A u following q- is not a true vowel but an indication of the quality of the consonant. Thus “quis” does not contain a diphthong. In “quae” the diphthong is ae. Both words are monosyllables. The same is true of other words such as cui. An apparent double vowel (-ii-) is two syllables, not a diphthong. The rule is sometimes blurred in that some two-syllable vowel combinations can be scanned as one syllable: dĕĭndĕ (trisyllabic) becomes dēindĕ (disyllabic). This is called synizesis.

c) In a line of verse the syllable is followed by two or more consonants. Thus, the first syllable of arma is long. In the phrase Ītaliam fatō, Ītaliam is a four-syllable word that consists linguistically of one long syllable (the initial I is long by nature) followed by three short syllables: _ ˘ ˘ ˘. But in the metrical context above, Ītaliam is scanned _ ˘ ˘ _, since the last vowel (-a-) is followed by two consonants.

Note: In some descriptions of Latin verse, this rule is expressed in terms of open and closed syllables. A syllable is open if it ends in a vowel, closed if it ends in a consonant; syllable division within a word places an internal consonant with the preceding vowel. A closed syllable is considered long metrically if it is followed by a syllable beginning with a consonant. It is considered short if it is followed by a syllable beginning with a vowel. I do not see the advantage of this explanation over the mechanical one above, which does not require defining the precise elements in each syllable.

c.1) The consonants x and z are considered double consonants.

c.2) A special case of double consonants concerns the combination of a mute (or “stop”) followed by a liquid. In Greek, the rule includes a mute followed by nasals m and n, but in Latin, m and n do not occur naturally in these combinations. Linguistically, the mutes can be analyzed as three sets: unvoiced (p, t, k); voiced (b, d, g); aspirate (f th, h) (k and h do not occur as mutes in Latin). Liquids are l, r. A syllable containing a naturally short vowel followed by the consonant combination of a mute and a liquid can be metrically long or metrically short. This rule applies only when the combination of the mute and liquid occurs in the same syllable: for example, the initial fr- in frāter. In a word such as oblino, composed of the separate elements ob- plus -lino, the two consonants are part of different syllables, and the syllable ob- would be considered long.

d) Exceptions. There are certain cases where the above rules for determining syllable length are not strictly applied. The most important involves what is known as brevis brevians. This rule is variously stated, but in its simplest form, a long syllable can be counted short if it is followed or preceded by a short syllable that itself has the “word accent,” or stress (see sec. B.3.1 below). Brevis brevians commonly involves disyllabic words: the word bŏnīs can be scanned as two shorts even when followed by a consonant combination. Fortunately for non-Latinists, whose notion of naturally long vowels may be hazy and flexible to begin with, this rule will not prove troublesome.

A.2. Elision and Hiatus

A.2.1. Elision

When a word ending in a vowel is followed by a word beginning with a vowel, the final vowel of the first word is elided, that is, it is dropped and not counted in the scansion of a line, and its quantity (long or short) is disregarded. In the phrase ille ego, the final -e of ille is dropped, and the entire phrase scanned _ ˘ ˘. In addition, a word ending in a vowel plus -m is treated as a word ending in a vowel; that is, the -um will be elided if it is followed by a word beginning with a vowel. In the phrase multum ille, -um is effectively dropped, and the phrase scanned _ _ ˘. For all practical purposes, the letter h is not considered (metrically) as a letter at all. Thus when a word ending in a vowel is followed by a word beginning with an h plus a vowel, the vowel of the first word is elided. The same rule applies when a word ending in vowel plus -m is followed by a word beginning with h plus a vowel: the final syllable of the first word is also elided. Certain common monosyllabic words are not elided, for example, dō (I give), spem (hope [accusative case]), quī (they).

A.2.2. Hiatus

Hiatus is most simply seen as an exception to the general rule of elision. It refers to specific cases where normal elision does not occur. Some cases are stylistic: Vergil, for example, might treat the initial h as a consonant in some words of Greek origin. Other cases of hiatus are metrical: in certain positions of the line, the implied break might be so prominent as to prevent elision.

A.3. Basic Substitutions

Rules of substitution are specific to verse type. In some verse types, substitution is based on quantity: two shorts are the metrical equivalent of one long. Thus in dactylic hexameter, a dactyl can be replaced by a spondee: _ ˘ ˘ is essentially equivalent metrically to _ _. In lyric verse, substitutions often involve single syllables: certain line positions can be occupied by either one short or one long syllable. Thus, the initial two syllables of an Aeolic line can be either long or short. Such a syllable is called anceps; in scansion it is generally marked with an x. Dramatic verse involves both types of substitutions (i.e., by quantity and by syllable length); in certain foot positions in a Latin iambic senarius (sec. B.1.4 below), the iamb (˘ _) can be replaced by a dactyl (_ ˘ ˘; long for the short in the first position, two shorts for the long in the second), a spondee (_ _; long for the short in the first position), or even ˘ ˘ ˘ ˘ (long for the short in the first position, and resolution of both longs as two shorts).1

A.4. The rules detailed in sections A.1–A.3 are sufficient to scan most common Latin lines: for example, the opening line of Vergil’s Aeneid:

arma virumque canō, Troiae quī prīmus ab ōrīs.

The naturally long vowels and diphthongs identify one set of long syllables:

![]()

To these can be added syllables that are “long by position,” that is, syllables that contain a vowel followed by two consonants:

![]()

Since each foot must contain either a dactyl (_ ˘ ˘) or a spondee (_ _), a little inspection and experimentation will show that there is only one way to fit six such feet into the above pattern. We can thus scan the line as follows; the break between feet is noted as a single vertical line (|):

The following line from Horace is scanned as a hendecasyllable (see sec. E.1 below); there is nothing that corresponds to a foot break, although Horace in this form conventionally has a word break following syllable 5, which some scholars represent with a single or double vertical line.

![]()

B. Elements of the Line: Foot and Metron, Caesura and Diaeresis, Word Accent and Verse Accent

B.1. Foot and Metron

Some Latin verse is organized by the foot (a minimal metrical unit); other verse is organized by larger metrical units, the metron or the colon, many of which cannot be usefully analyzed in feet. The types of feet frequently invoked in discussions of verse in English are iamb, trochee, spondee, dactyl, and anapest.

B.1.1. Disyllabic Feet:

|

iamb |

˘ _ |

|

trochee |

_ ˘ |

|

spondee |

_ _ |

|

pyrrhic |

˘ ˘ |

B.1.2. Trisyllabic Feet:

|

dactyl |

_ ˘ ˘ |

|

anapest |

˘ _ _ |

Less common trisyllabic feet are the following:

|

cretic |

_ ˘ _ |

|

bacchiac |

˘ _ _ |

|

amphibrach |

_ _ ˘ |

|

molossus |

_ _ _ |

|

tribrach |

˘ ˘ ˘ |

Other forms of trisyllabic feet include the palimbacchiac: _ _ ˘ (a “backward bacchiac”). It is doubtful whether the molossus and tribrach should be considered true feet, since they clearly could not be the basic units of a verse, and they are rarely used in descriptions of basic verse patterns; they occur (as does the disyllabic spondee) as possible substitutions for other feet in dramatic verse (sec. F.2 below).

B.1.3. Four-Syllable Feet:

|

choriamb |

_ ˘ ˘ _ |

|

ionic |

˘ ˘ _ _ |

The choriamb is the most common of these; a form such as the proceleusmatic (˘ ˘ ˘ ˘) occurs as a possible substitution in some verse feet (e.g., in some iambic verse), but it is not a basic unit of any verse type.

B.1.4. The Metron

Some verse lines are formed by larger units of feet, and in some cases it is useful to speak of this unit as a metron (pl. metra). Thus, in Greek, an iambic trimeter is conventionally analyzed as three groups of metra, each metron composed of two iambic feet. The equivalent meter in Latin is the iambic senarius (a line of six metrical feet; see sec. F.2.1 below). The reason for this difference has to do with the Greek and Latin rules regarding each unit. In Greek, the rules of substitution that apply to feet 1, 3, and 5 are different from those that apply to 2, 4, and 6, but the rules that apply to each of the three four-syllable units are essentially the same. In Latin, the same rules of substitution apply to each foot.

B.1.5. Units longer than the foot or metron are sometimes known as cola (sing. colon). Among the commonly named cola is the glyconic, characterized by an internal choriamb (_ ˘ ˘ _): x x _ ˘ ˘ _ ˘ _. Without the final long syllable, the colon is a pherecratean (x x _ ˘ ˘ _ >); with the addition of a final syllable, it is a hipponactean (x x _ ˘ ˘ _ ˘ _ >). Some scholars of metrics analyze these lines as consisting of four feet; others describe them as containing a moveable internal dactyl. But lines that do not consist of repeating units of feet or metra are most easily analyzed by considering the line itself (the colon) as the basic unit.

B.2. Caesura and Diaeresis

B.2.1. Caesura

There are two meanings of the word caesura. The general sense applicable particularly to French verse is a prominent syntactic break in a line (see chap. 3, C). While this can apply to some Latin verse, the technical sense relevant to most Latin verse is a word break that occurs within a verse foot, that is, a word break that does not correspond with a foot break. When discussing Latin verse, I will confine the word to this meaning. Most dactylic hexameters have a caesura in the third foot, marked here with a double vertical line:

In such verse, the word break does not correspond to the foot break in the third foot. Some lyric forms do not permit word breaks in certain positions, and this may be indicated in some systems of scansion by joining the syllable marks _ ˘ ˘ (_ ˘ ˘), or by an inverted ˘ ![]() Such a position is known as a bridge.

Such a position is known as a bridge.

B.2.2. Diaeresis

A diaeresis is the coincidence of a foot break and a word break. In some verse, the placement becomes so conventional that it is given a name; a word break occurring between the fourth and fifth feet of a dactylic hexameter, for example, is the bucolic diaeresis (see sec. D.1.4 below). An example is the opening line of Vergil’s Eclogues:

B.3. Additional Elements of Line Structure

B.3.1. Word Accent vs. Verse Accent

Linguistically, every Latin word has a word accent (a stress). This accent can occur on either a long or a short syllable.2 The word accent, also called a phonetic accent or linguistic accent, is different from the verse accent (or ictus). The verse accent is simply the long syllable in the foot (the second syllable of an iambic, the first of a trochee). Verse accent has nothing to do with the linguistic stress (word accent) of the word itself. Word accent is disregarded in Greek verse; in Latin verse, it is generally a secondary matter, although certain verse types have rules or conventions that involve this accent.

B.3.2. Arsis and Thesis

In Latin, the arsis is generally (but not always!) considered the heavy or long element of a verse foot; the thesis is the unstressed element; for an iamb (˘ _), the arsis in the Latin sense is the second syllable; the thesis the first. These terms are ambiguous, since they can be used in exactly the opposite sense of the one defined here. Latin verse can be easily described without them.3

B.4. English Imitations and Versions

There are many ways of imitating Latin verse or verse forms in English. To do so requires defining the English equivalent of the linguistic distinction between long and short syllables. Most English writers represent this in English as a difference between stressed and unstressed syllables; that is, the quantitative distinction (long vs. short) is transformed into one involving stress (stressed vs. unstressed). Thus the word living in English would be scanned as a two-syllable word with a stress on the first syllable: X x, that is, as a trochee. But there have been attempts to apply rules of quantity directly to English verse. The word living would be scanned differently under these rules: if one disregards the linguistic stress, the word can be scanned as a short syllable (liv-) followed by a long one (-ing, long due to the consonant combination in -ng). Quantitatively, the word liv-ing can thus be scanned ˘ _, that is, as an iamb.4 See chapter 5 for examples from Renaissance writers.

C.1. Basic line types based on feet include such forms as (a) dactylic hexameter: a line consists of dactyls or their equivalent organized in six feet; (b) iambic senarius: a line consists of iambs organized in six feet; (c) trochaic septenarius: a line consists of seven trochaic feet.

C.1.1. Trochaic and iambic line types (sec. F) are often described as lacking the final syllable and thus catalectic; lines described as lacking the initial syllable of the first foot are called “headless” or acephalic. Thus a catalectic trochaic septenarius consists of seven feet of trochees, lacking the final short syllable.

C.2. Meters can also be based on metra (the Greek equivalent of the Latin iambic senarius is called a trimeter: three metra, each consisting of the equivalent of two iambic feet). Others are based on larger units of the colon or the line itself (see secs. B.1.4 and B.1.5 above). Irregular cantica (sec. H) would be analyzed by cola as would the Aeolic verse described below (sec. E).

C.2.1. The hendecasyllable is an eleven-syllable line, whose most common form in Latin is associated with Catullus: _ x _ ˘ ˘ _ ˘ _ ˘ _ ˘; the form in Greek is associated with Sappho: _ ˘ _ x _ ˘ ˘ _ ˘ _ _. Both forms are occasionally analyzed in feet (for example, the Catullus hendecasyllable might be analyzed as a trochee, a dactyl, and three trochees), and they can also, with difficulty, be seen as forms of the eight-syllable glyconic (see sec. B.1.5 above). But little is gained by such gymnastics; it’s easier simply to write the scansion out.

D.1. Dactylic Hexameter

We have used this line type to illustrate many of the principles of Latin versification. A basic description of the line in terms of feet is as follows:

![]()

In English, the dactylic hexameter is often written in an accentual form, as in Longfellow’s Evangeline: “This is the forest primeval, the murmuring pines in the hemlock.”

D.1.1. A spondee can be used in place of a dactyl in any of the first four feet. In Latin, such a substitution in the fifth foot is so rare as to be considered impermissible.

D.1.2. Word accent in a Latin hexameter invariably coincides with verse accent in the fifth and sixth feet. In Greek verse, there are no rules regarding word accent, and spondees are admitted in the fifth foot.

D.1.3. Caesura

A caesura (in the strict sense) generally occurs in the third foot of a dactylic hexameter. And classical Latin verse generally avoids the coincidence of word break and foot break (diaeresis) in the first part of the line.

arma virumque canō ‖ Troiae quī prīmus ab ōrīs

Although the caesura appears to be an ornamental matter, it is nearly essential to the classical form of the dactylic hexameter. And while a line with word breaks corresponding to foot breaks between feet 2, 3, and 4 might not be considered unmetrical in a technical sense, it certainly would have been so considered by classical Latin writers.

D.1.4. A common position for the diaeresis in the dactylic hexameter is before the fifth foot. It is called the “bucolic diaeresis” since it was felt to be a characteristic of Greek pastoral poetry.

Thus, a typical pattern showing both caesura and bucolic diaeresis might be:

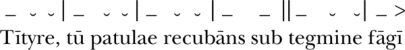

![]()

An example showing both is the first line of Ovid’s Metamorphosis:

In nova fert animus ‖ mūtātās ‖ dīcere formās

D.1.5. Practical Implications

The implications for scansion of a line are simple, and lines can be scanned even by those who cannot determine what vowels are naturally long. A line of classical dactylic hexameter can be scanned by following a set of logical steps:

a) The last five syllables are known: _ ˘ ˘ | _ > (D.1.1).

b) The first syllable of the line must be long.

c) All syllables involving a vowel followed by two consonants are long (A.1c).

d) Final vowels -o, -i, and -u are nearly always long by nature (A.1a, note).

There are a number of further steps one could take. The following are all logical consequences of the pattern of long and short syllables the hexameter requires:

a) Any syllable falling between two long syllables is long.

b) Any syllable falling between two short syllables is long.

c) Any syllable following the combination _ ˘ is short.

d) Any syllable following two short syllables is long.

Since there are a known range of syllables in each set of feet, if after marking off, say, four feet, there are six syllables remaining, those two feet are dactyls. If there are five, what remain are a dactyl and a spondee.5 Most important, because many hexameter lines can be accurately scanned by applying even a few of these sketchy principles it is almost pointless for non-Latinists to dwell on those lines that give problems. Even without the aid of marked long vowels, scansion of the following lines is almost mechanical:

———

[The spirit drives me to speak of forms changed into new bodies. Gods, inspire me in these beginnings (for you change them as well).]

See further examples in appendix (chap. 2, D.1).

D.2. Elegiac Couplet

An elegiac couplet is a two-line form consisting of a line of dactylic hexameter, which uses the conventions above, followed by what is often called a pentameter, which is scanned as follows:

![]()

Each half-line in the pentameter can be called a hemiepes. The double vertical line corresponds to a word break; this break is generally described as a diaeresis, although it is also occasionally described as a caesura. In the pentameter, spondees may be substituted for dactyls in the first half-line; no substitution is permitted in the second halfline, and there is no necessary relation between word accent and verse accent. In contrast to the dactylic hexameter verse form, the syntax of the elegiac couplet generally supports line structure; that is, each couplet consists of a single, autonomous syntactic unit. Because this verse type was often taught in schools, examples are numerous in medieval and Renaissance Latin poetry, and it is a common form in Ovid:

———

[You will go, little book, unenvied to the city without me; because, alas, I am not allowed to go as your master. Go unadorned, as it is appropriate for an exile to be; miserable, wear the habit of this age.]

The lyrics most familiar to students of classics and thus most often imitated by English poets are those of Catullus and Horace. They consist mainly of Aeolic verse forms borrowed from the Greek poets Sappho and Alcaeus and found also in Greek drama. Aeolic forms do not consist of feet, although they are occasionally analyzed in those terms. A line in Aeolic verse is characterized by an internal choriamb (_ ˘ ˘ _) preceded by what is called an Aeolic base, that is, two syllables that are anceps, either long or short. A common form is the glyconic (see sec. B.1.5 above), analyzed as follows:

![]()

The verse can be “compounded”; that is, additional syllables can precede the base. The choriambic element can also be doubled to form different line types. What is called a lesser Asclepiad adds one choriamb: x x _ ˘ ˘ _ _ ˘ ˘ _ ˘ >; and a greater Asclepiad adds two (discussed in sec. E.3.1 below). A long syllable can be resolved as two shorts in the Aeolic base, but no substitution (long for short) or resolution (two shorts for one long) is permitted after the base.

E.1. Hendecasyllable

The form of Aeolic verse associated with Catullus consists of repeating lines of eleven syllables scanned as follows: x x _ ˘ ˘ _ ˘ _ ˘ _ >. The first part of the line is a glyconic (sec. B.1.5 above).

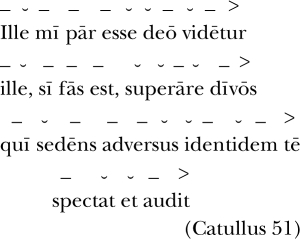

E.2. What are called Sapphics are four-line stanzas. The first three lines are hendecasyllables, scanned _ ˘ _ x _ ˘ ˘ _ ˘ _ >; these are followed by a single line scanned _ ˘ ˘ _ >. The following is the first stanza of Catullus’s Latin translation of Sappho:

———

[He seems to me to be like a god, or (if it is right) to surpass the gods—that man who sitting across from you sees and hears you [sweetly laughing]]

The form is also common in Horace, whose version of the Sapphic hendecasyllable has a word break following syllable 5: _ ˘ _ x _ ‖ ˘ ˘ _ ˘ > Metrically, the Sapphic hendecasyllable may be analyzed as a cretic (_ ˘ _) followed by a hipponactean (x x _ ˘ ˘ _ ˘ _ _) with a curtailed Aeolic base of one anceps (x); but the full pattern of the line itself is easier to memorize than this somewhat dizzying formula. The Sapphic form is often imitated (visually and metrically) by English poets.

E.3. Asclepiads

An Asclepiad is a form of Aeolic that uses one of the following four line types:6

a) lesser Asclepiad: x x _ ˘ ˘ _ _ ˘ ˘ _ ˘ _

b) greater Asclepiad: x x _ ˘ ˘ _ _ ˘ ˘ _ _ ˘ ˘ _ ˘ _

c) glyconic: x x _ ˘ ˘ _ ˘ _

d) pherecratic: x x _ ˘ ˘ _ _

E.3.1. Asclepiads are classified by types. Five Asclepiad types are found in Horace, and other types are also possible. Scholars agree on the forms and classifications of Asclepiads but differ on how they should be numbered; I give Raven’s numbering below, although standard accounts vary:7

I: uses a alone

II: uses b alone

III: four-line stanza: c, a, c, a

IV: four-line stanza: a, a, a, c

V: four-line stanza: a, a, d, c

Because of the rarity of substitution, the practical matter of scanning Asclepiads for a non-Latinist requires no more than imposing upon a four-line stanza whatever form works.

E.3.2. Example of an Asclepiad from Horace, Odes 1.5 (Asclepiad V in system above; variously categorized as III or IV under other systems):

———

[What beautiful boy, fragrant in perfumes, among the roses, urges you in a welcome cave, Pyrrha, for whom do you tie your golden hair . . .]

E.4. A variant of Aeolic verse common in Horace is the Alcaic, a four-line stanza scanned as follows (the first two lines are a form of the hendecasyllable, with a word break after syllable 5):

For an example of the Alcaic form found in Horace see appendix (chap. 2, E.4).

E.5. In the Latin Sapphics of Horace, four-line stanzas usually consist of a complete sentence and end with a full stop. In most of these Aeolic types, no relation between syntax and line and stanza structure is necessary; that is, sentence periods can continue from one stanza to the next. Thus, in Asclepiad types I–III, the four-line stanzaic unit may not be readily apparent.

These common verse types occur in two main forms: dramatic and non-dramatic. The non-dramatic form is no more complex than other meters, but the rules for the dramatic form are both and controversial. In both difficult forms, rules for substitution can involve principles of quantity (two shorts are considered equal to one long) and isosyllabism (one short syllable equals one long).8

F.1. Non-dramatic Forms

Basic non-dramatic forms are usually described in terms of metra rather than in terms of feet. That is, a non-dramatic twelve-syllable iambic line in Latin is conventionally called a trimeter (three four-syllable units), rather than a senarius (six two-syllable feet).

F.1.1. Iambic Trimeter

In an iambic trimeter, three metra of iambs are combined to form a twelve-syllable line. The basic form is as follows:

———

[Now, I give my hands as a suppliant to efficacious knowledge and pray through the realms of Proserpina]

Substitutions: The first syllable of each four-syllable metron can be long or short. Two shorts can be substituted for a long in any but the last position. There is generally a word break after the fifth syllable.

F.1.2. A trochaic example of non-dramatic verse is the catalectic trochaic tetrameter. This line has four metra, each consisting of two trochees; the last syllable is lacking (catalectic). The final syllable of each metron can be long or short, and a break (in this case diaeresis) generally occurs after syllable 8. The basic form is as follows:

![]()

In this example from Seneca’s Phaedrus, ordinary substitutions are seen in metron 1: the long in position 3 is resolved as two shorts; the anceps syllable in position 4 is long:

There are no restrictions on substitutions, but there are generally, in any given group of lines, fewer such substitutions than in the comparable iambic line (sec. F.1.1 above).9

F.2. Dramatic Forms

In Latin, the dramatic versions of iambic and trochaic lines are described in terms of feet, not metra, and the same rules of substitution apply to each foot (in non-dramatic forms of iambics, substitutions are not permitted in even-numbered feet).

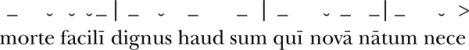

F.2.1. The most common dramatic line type is the iambic senarius. The basic form is as follows:

![]()

x is anceps; thus it can be either long or short, producing two possibilities for each foot: ˘ _ and _ _. However, any long syllable may be resolved as two short syllables. Thus any of the following foot types are possible: ˘ _, ˘ ˘ ˘, _ _, _ ˘ ˘, ˘ ˘ _, and ˘ ˘ ˘ ˘. This line type seems to admit nearly anything, but examination shows the following feet are not permitted: _ ˘, _ ˘ _, etc. In addition, rules governing exceptions, such as brevis brevians, operate more freely, and many long syllables can be shortened that would not be shortened in other verse. In general, scanning even basic lines is not a reasonable thing to ask of anyone other than a skilled Latinist:

For additional examples see appendix (chap. 2, F.2).

F.2.2. The second most common dramatic line is the catalectic trochaic septenarius: seven feet of trochees; the last syllable is dropped. A diaeresis usually occurs after the fourth foot, which makes the last half of the line metrically identical to the last half of an iambic senarius (see sec. F.1.2, note 9). The same substitutions that are found in the iambic senarius are permitted, but they are less frequent. The form is often seen at the end of Terence’s plays:

F.2.3. Other iambic and trochaic dramatic meters include the iambic septenarius (seven feet of iambs), the trochaic octonarius (eight feet of trochees), and many other forms. Since various forms can be mixed, almost arbitrarily, even in a single passage of dialogue, most editions of Terence or Plautus come with an index of meters.10

In classical Latin and Greek verse, the possible combinations of feet and verse types are numerous: lines can be built based on anapests, bacchiacs, or even cretics. Of special note is the epode. The general definition of an epode is a distich of two lines formed of line types that often use different metrical bases. Among many variants in Horace is a couplet formed with a line of dactylic hexameter followed by an iambic line:

———

[It was night, and the moon shone in the clear sky among the lesser stars]

Found in the plays of Plautus, the cantica is a long form that consists of irregular mixtures of rhythmic patterns and types. It may be dominated by a verse type (or type of foot), although this is not a necessary criterion of the form. What appear to be individual stanzas or units are potentially repeatable but are not necessarily repeated in the text.11 Thus, in any cantica, no line structure can be predicted from the structure of the preceding line, and this is tantamount to saying that no abstract analysis is possible apart from specific examples.

Texts: All texts are adapted from Oxford Classical Texts editions; all translations are mine.

References: Joseph H. Allen, J. B. Greenough, et al., Allen and Greenough’s New Latin Grammar for Schools and Colleges (1888; numerous re-editions); D. S. Raven, Latin Metre: An Introduction (London: Faber and Faber, 1965). James W. Halporn, Martin Ostwald, and Thomas G. Rosenmeyer, The Meters of Greek and Latin Poetry (1980; rev. ed. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1994); M. L. West, Introduction to Greek Metre (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987).

1. There are several ways of representing such substitutions, and some schemes simply list the potential substitutions singly: ˘ _ / ˘ ˘ ˘ / _ _ / _ ˘ ˘ / etc. Although an anceps syllable is written x, there is little practical difference between x, _ / ˘, and other ways of indicating this. Final syllables that are similarly long or short are conventionally represented with the symbol >.

2. In Latin, the placement of word accent is regular and follows specific rules. In disyllabic words, the accent is on the first syllable. In multisyllabic words, when the next to last syllable is long, that syllable contains the word accent. When the next to last syllable is short, the preceding syllable contains the accent.

3. The terms unfortunately are not avoided in standard discussions of classical verse. In classical Greek, “arsis” referred to the raising of a real foot in marching; “thesis” referred to the placing of the foot down on the ground. Thus the thesis in Greek verse was the “beat” (in music, the downbeat—the OOM, in OOM pa pa) and the same as the verse accent. In a dactyl, the thesis was the first long, the arsis the remaining shorts. In Latin, this terminology was reversed: the “arsis” became the implied “raising” of the voice in stress, and thus, the arsis of the dactyl in Latin verse was described as the initial long (the verse accent), and the thesis the rest of the verse. Nineteenth-century scholars of early Germanic verse imposed the Latin misuse of these terms onto Germanic verse, although its underlying system had nothing to do with either Greek or Latin. Curiously, some early twentieth-century Greek grammar books adopted the Latin use as well, while some of the most important Latin grammar books returned to the Greek form. Useful as these terms might be, only the person using them can be certain of their intended meaning.

4. A useful exercise for English students for understanding the implications of quantitative meter is to begin with a well known and heavily accented line such as a limerick: “There wás a young lády of Róme,” scanned x X x x X x x X. This pattern can then be reproduced using quantitative rules (˘ _ ˘ ˘ _ ˘ ˘ _): “a young woman of Tripoli.” Here, long syllables are those with a vowel followed by two or more consonants (young and of are scanned long), and the linguistic accent is disregarded (woman is thus scanned as two shorts).

5. Another such rule pointed out to me: (total number of syllables in a line) - 12 = (number of dactyls in that line).

6. The lesser Asclepiad adds one choriamb to a glyconic; the greater Asclepiad adds two choriambs. In Horace, the syllables marked x in these Aeolic verses are generally long. Obligatory word breaks between adjoining choriambic elements in the greater and lesser Asclepiad also appear, e.g., x x _ ˘ ˘ _ ‖ _ ˘ ˘ _ ˘ _ and x x _ ˘ ˘ _ ‖ _ ˘ ˘ _ ‖ _ ˘ ˘ _ ˘ _.

7. The numbering in the once-standard grammar of Allen and Greenough is: I: a alone; II: c, a, c, a; III: a, a, a, c; IV: a, a, d, c; V: b alone. Other numberings include: I: a alone; II: a, a, a, c; III: a, a, d, c; IV: c, a, c, a; V: b alone. Among additional Asclepiad types is c, c, c, d—three glyconics followed by a pherecratic—as found in Catullus 34.

8. Paradoxically, this was the form most familiar to early schoolboys, who used phrasebooks made out of the dialogue of Terence. Some editions of these phrasebooks and early printed editions of Terence as well show that their readers and editors were unaware of or indifferent to the fact that Terence was in verse.

9. The catalectic trochaic tetrameter is indistinguishable from what in dramatic verse is called trochaic septenarius (sec. F.2.2 below). Note that the diaeresis in the trochaic line produces the same metrical scheme following it as does the caesura in the comparable iambic line.

10. Modern editions conventionally identify the meter of each line, and some mark the ictus of each metron, thus in the example from section F.2.2 above, the first element of each four-syllable metron: “Égo deorum vítam eampropter sémpiternam esse árbitror.” Even with such aids, non-Latinists and Latinists alike may have difficulty with these lines.

11. Latin cantica do not follow the common Greek form, which consists of a repeating three-stanza unit of strophe, antistrophe, epode (where strophe and antistrophe are metrically identical).