Syllabic Verse

French

A.1. In syllabic or isosyllabic verse (the terms are effectively synonymous), the verse line is defined strictly in terms of number of syllables. Theoretically, lines of any length are possible, although metricians claim that lines over eight syllables must have other features, such as internal caesurae or regular stress patterns, to be metrically in telligible to listeners. French twelve-syllable lines are thus in units of six syllables; some longer English verses are organized by accentual rhythms. In purely syllabic or isosyllabic verse, only the number of syllables matters, and there are no supplemental rules regarding accent or quantity. Examples in English include the verse experiments of Marianne Moore and Robert Bridges (chap. 6, B.2). Classical French verse, although usefully classified as syllabic or isosyllabic, incorporates supplemental rules of accent.

A.1.1. Most histories of French verse distinguish major periods and schools as follows: Old and Middle French (1100–1500); Grands Rhétoriqueurs (1460–1520); Pléiade (sixteenth-century; major figures include Ronsard and DuBellay); classicists (seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; major figures include Malherbe, Corneille, Racine, Boileau); Romantics (Hugo, Baudelaire); Moderns (Verlaine, Apollinaire). These schools differ on various details of versification: rhymes or scansions that are accepted in the nineteenth century might not be accepted in the seventeenth century; others might be rejected as old-fashioned. All agree, however, on two basic principles: (1) French verse is isosyllabic, in the sense that the foundation for the line is a particular number of syllables that are not distinguished in terms of accent or syllable length; (2) the definition of syllable and even of rhyme is conventional; that is, the prosodic syllable is not a matter of phonetics or a function of the way the language is spoken.

A.1.2. French literature has a conservative and self-conscious critical history. Many details in Eustaches Deschamps’ Art de Dictier, a treatise on poetic form in the late Middle Ages, are applicable to nineteenth-century French verse; and many of the innovations of modern French verse are based on modifications of classical rules and conventions.

A.2. Metrics vs. Stylistics

The difference between metrics and stylistics is an important one, and I have tried to limit my discussion below to metrics, that is, rule-bound features that are fundamental to verse. A metrical rule determines the difference between what might be called “legal” and “illegal” verse, whereas a stylistic rule might distinguish a “good” verse from a “bad” one.

A.2.1. Discussions of French meter often conflate metrics and stylistics, beginning with such considerations as rhythm. Rhythm, difficult to define, includes such features as grammatical structure, secondary accent, even rhetorical and performative elements forming the phrase structure of individual lines. However basic these elements might seem, they tend toward the level of stylistics, that is, they are not matters of rules of versification. Furthermore, one cannot analyze such elements without more than a basic knowledge of the language (see sec. D.1 below on the flexible and movable coupe).

A.3. Definitions

A.3.1. Syllable

Syllables in classical French verse are not defined phonetically, and the number of syllables in spoken French is not the same as the number of syllables in verse. French verse defines syllables as they were pronounced during the early history of French as spelling was formalized. This means that a syllable is defined roughly as the syllable represented by the word’s spelling. The word chose, for example, is in spoken French one syllable (it has what is called terminal e-mute). In verse, this terminal -e counts as a syllable, and the word has two syllables.1

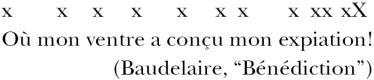

A.3.1.1. The opening line of “Bénédiction” from Baudelaire’s Fleurs du Mal might be pronounced as ten syllables. In verse, it has thirteen: lorsque is two syllables (one in spoken French); puissances three, suprêmes also three (both have two syllables in spoken French). In my representations below, I use a lowercase x to represent one verse syllable.

![]()

A.3.1.2. Internal -e-, ordinarily not pronounced in spoken French, has full syllabic value in verse, unless it follows an unaccented vowel: thus ornement counts as three full syllables, as does flamboiements (-e- does not constitute a syllable).

A.3.2. Vowel Combinations

Certain vowel combinations are diphthongs, that is, they count as one syllable. Others are disyllabic. Among the more common diphthongs are ai, au, eu, eau, oi. Some vowel combinations can count as one or two syllables: ie, ien, io, ue, and ui.

A.3.2.1. The basis for this pronunciation or prosodic value is often etymological: if the French word comes from a Latin word where the two vowels were separated or pronounced as two syllables, the modern French word is generally a disyllable: lion from leo; suer from sudare. If the French vowels evolve from a single Latin vowel, the monosyllabic pronunciation is retained: fait from factum (the French -ai- is formed from the Latin -a-); fier from ferus (the French -ie- is formed from the Latin -e-). Old French terminations -ions, -iez of the imperfect are disyllabic. In Modern French, these same endings are prosodically monosyllabic, but if preceded by a mute consonant (p, t, k, etc.) plus a liquid (l or r), they are disyllabic (for these consonant combinations in Latin, see chap. 2, A.1). The disyllabic pronunciation is called diaeresis (e.g., pri-ons); the monosyllabic pronunciation is called syneresis (e.g., all-ions). Many cases are controversial: ei preceded by mute plus liquid is often disyllabic; pleinne thus can have three syllables (so Corneille); the Academy claimed this should be two.

A.3.2.2. However abstruse these rules, for readers of classical French poetry, even those with minimal knowledge of French, the words involved pose more difficulties in theory than in practice; the required number of syllables in a line will determine how such syllables are counted.

A.3.3. Pronunciation

In all cases, to say how a word is pronounced in verse refers only to its status in the composition of verse (for example, does a particular unit count as a syllable or does it not count as a syllable? does it qualify as a rhyme?); there are no absolute rules or conventions governing how readers of verse (whether professional actors performing classical drama or amateurs) are to pronounce these lines.

A.4. Tonic Accent

Multisyllabic French words have one primary accent, which in spoken French occurs on the final syllable. This is called the tonic accent. Elements following this accent, generally grammatical inflections, are not pronounced in spoken French but count as full syllables in French verse. In the line above, two words that are disyllabic in speech are trisyllabic in verse: puis-SANC-es, su-PRÊM-es. In speech, the terminal -es would not be pronounced.

A.4.1. The most common grammatical inflection is a final, unaccented -e, conventionally called e-mute, or e-caduc, and special rules apply for its treatment. For plural feminine nouns and adjectives, this terminal -e becomes -es. In spoken French, blanche and blanches are monosyllabic and indistinguishable; in French verse, they are disyllabic and the terminal -s in the plural is sounded (but see qualifications above, sec. A.3.3). The word accent remains the same in spoken and poetic French.

A.4.1.1. Non-French speakers can easily determine the position of the accent in regard to e-mute endings by a simple convention of orthography. For any multisyllabic word, a terminal -e or -es that is pronounced in spoken French receives the word accent, and that accent will be noted typographically with an acute accent. If there is no printed accent on such a termination, then the ending is mute in spoken French and in verse constitutes a “post-tonic” syllable, that is, the accent is on the preceding syllable. Thus bonté is disyllabic both in speech and in verse, with a terminal accent on the é; conte is monosyllabic in speech, but disyllabic in verse, with the tonic accent on the first element: CONT-e.

A.4.2. Similar to the e-mute are certain other inflectional endings: for example, the terminal -ent in the word confondent, the third person plural of the verb confonder [to confound]. In speech, this -ent is not pronounced and the word has two syllables; in verse, the final -ent is pronounced but the accent remains on the preceding syllable.

A.5. Basic Definition of Verse Line

A line in most French verse is defined (or counted) in terms of the final tonic accent in that line. Thus a decasyllabic line is defined as a line with a final, tonic accent on syllable 10; an Alexandrine as a line with a final, tonic accent on syllable 12. Since unaccented inflectional endings may follow this tonic accent, the actual number of syllables in a given line can be greater.

A.5.1. For most lines in French, the scansion is purely mechanical and is no more difficult for those who do not know French than for those who do; in lines of twelve syllables, there is a terminal accent on syllable 12 (I represent this accent with an uppercase X).

This is a twelve-syllable line (an Alexandrine). If this same line were spoken, there would be ten syllables (although this would depend on the treatment of -que in Lorsque):

![]()

A.6. Elision

As in Latin, French verse has rules of elision. In verse, post-tonic terminal syllables ending in vowels are elided when followed by words beginning with a vowel. Thus the phrase “ventre a conçu” below:

The terminal -e in ventre, normally pronounced in verse, is elided: “ventr(e) a”. In the phrase “Elle ravale ainsi” the -e in Elle is counted as a syllable, but the -e in ravale is elided due to the following ainsi.

A.6.1. Elision does not occur in certain line positions of particular verse types. Post-tonic vowels at the end of the line are not elided with the beginning of the next line. In some medieval verse, a posttonic vowel at the mid-line caesura would also not be elided (see sec. C.1.2 below on epic caesura).

A.6.2. In chapter 2, I treated hiatus as the exception to elision in classical Latin and Greek verse. For French verse, hiatus is more important. Linguistically, hiatus is the break between two vowels (in a single word, nu-ée). For French verse, the most important case is the pause between the terminal and initial vowels of succeeding words in such common phrases as “tu a,” “ni elle,” “ou on,” etc. In classical French verse, these combinations are generally not permitted. In pre-classical French verse, hiatus involving a terminal and initial vowel was permitted only at the caesura (a conventional mid-line break), as in this line by Ronsard:

Je n’ay jamais servi ‖ autres maistres que rois.

The phrase “servi autres” would not be permitted in classical French verse.

A.7. Further Consequences of Classical Rules

For most words, the classical rules of French verse are unproblematic: the word monde, normally pronounced as a monosyllable, is pronounced as two syllables in verse. But for certain words the difference between normal pronunciation and syllable count in verse became intolerable to French sensibility, for example, feminine nouns and adjectives whose singular ends in accented -ée. In spoken French, the endings -é, -ée and their plurals -és, -ées are identical in pronunciation. Under the strict rules of verse, a word such as nuée [cloud], or its plural nuées, should be three syllables (nu-E-e). But pronouncing this final syllable, as the rules of classical prosody would require, produces two examples of hiatus. The rule was thus established that these words could only be used at the end of a line, or if the final -e could be elided with the following word. Thus, the pronunciation nu-é-es was avoided (or seemed to be avoided). And one set of artificial rules (the pronunciation of a mute -e) was trumped (or salvaged) by another (post-vocalic e-mute could only be used in cases where it would not have to be pronounced).

A.7.1. French “clouds” thus only appear at the end of a French line, never in the middle. And there are no “white clouds” (des nuées blanches) anywhere to be found in French classical verse simply because there are no positions in French decasyllabic or Alexandrine verse where such a common phrase would be metrically acceptable.

A.7.2. Many other common words also cannot be used in the interior of the verse. The plural vies (“lives,” sing. vie) cannot appear except in the final position of a line, because by rule the terminal, post-tonic element (-es) ought to be elided but cannot be elided due to the final -s.

B.1. The earliest systematic treatises on French verse in the Middle Ages analyzed verse types according to the number of syllables in a line and recognized lines from one to fourteen syllables in length. Victor Hugo acknowledges this tradition in his poem “Les Djinns,” written in a stanza formed of lines of two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, and ten syllables. One curious phenomenon in French is that stanzas with lines of an odd number of syllables tend to be based on music, and this feature is also worth checking for certain early English verses as well (e.g., in the songs of John Donne, chap. 6, D).

B.2. The line types that have received the most critical attention in French verse are those of eight, ten, and twelve syllables, that is, those showing an even number of syllables. The octosyllable, generally in rhymed couplets, was a standard form for much narrative verse in Old French (chivalric romances, beast epics, fabliaux). The decasyllable was used in ballades, courtly stanzaic forms, and some epic poems (Chanson de Roland). Certain military epics (chansons de geste) were in stanzas composed of twelve-syllable lines (Alexandrines). The word Alexandrine is derived from the twelfth-century epic on Alexander the Great composed in such lines.

B.2.1. Octosyllable

The octosyllable is a line with a terminal accent on syllable 8. There are generally no required breaks in mid line. The most common form is in rhymed couplets.

La damoisele estoit si bien

de sa dame, que nule rien

a dire ne li redotast

a quoi que la chose montast.

(Chrétien de Troyes, Lancelot [twelfth century])

B.2.2. Decasyllable

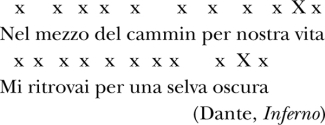

A decasyllable is a line with a terminal accent on syllable 10. This terminal accent may be followed by one (or theoretically more than one) unaccented syllable, a syllable that would not be pronounced in modern French pronunciation. Thus a decasyllabic line has the basic metrical form:

![]()

Most decasyllabic lines will have a real or implied break following syllable 4:

De mon vrai cuer ‖ jamais ne partira

L’impressïon ‖ de vo douce figure

(Machaut, Le Livre du voir dit)

A few medieval variants of the decasyllable show this break following syllable 6, dividing the line 6/4, as in Aiol, a thirteenth-century chanson de geste. Other decasyllables are without a caesura.

B.2.2.1. Italian Variants. The French decasyllable has the same form as the Italian hendecasyllable (eleven-syllable line), the most basic line in Italian poetry. An Italian hendecasyllable is defined exactly as is the French decasyllable: a line with a terminal accent on syllable 10. Because of the nature of Italian grammar and prosody, most of these lines will in fact be of eleven syllables; some will be of ten and others of twelve syllables.

B.2.3. Alexandrine

The Alexandrine is the most important line in French literary history. It is defined as a line of twelve or more syllables with a terminal accent on syllable 12. The classical Alexandrine shows a caesura following accented syllable 6 and the line itself consists then of two hemistiches.

In French verse, a caesura is a mid-line syntactic break. The caesura cannot appear, for example, in the middle of a prepositional phrase or between a subject pronoun and verb. It is not the same as the caesura defined in Latin verse (see chap. 2, B.2). All classical forms of the Alexandrine have some kind of caesura and strict rules regarding its placement. Many forms of decasyllabic verse have a caesura as well. In the classical Alexandrine, the caesura regularly follows syllable 6. In the decasyllable, the most common form of caesura follows an accented syllable 4. I represent it here with a double vertical line (‖). In many analyses of verse, it is represented by a single or double virgule (/ or //).

C.1. Theoretical Forms of the Caesura: Classical, Epic, Lyric

The most common form of caesura is the classical caesura, which immediately follows a mid-line terminal tonic accent. Two other forms, associated largely with medieval verse, are the epic caesura and the lyric caesura. These occur when the caesura follows an unaccented terminal syllable. If that syllable is counted in the line analysis, the caesura is a lyric caesura; if it is not counted, the caesura is an epic caesura.

C.1.1. Classical Caesura

In the Alexandrine, the classical caesura divides the line into two six-syllable hemistiches:

Decasyllabic verse is rare after the medieval period, but Ronsard in “Des Amours” shows regular, classical caesura after syllable 4 (marked in the lines below):

Ces diamans, ‖ ces rubis, qu’un Zephyre

Tient animez ‖ d’un soupir adouci,

Et ces oeillets ‖ et ces roses aussi,

Et ce fin or, ‖ où l’or mesme se mire . . .

C.1.2. Epic Caesura

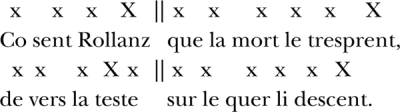

The epic caesura is a basic form of caesura found in the eleventh-century Chanson de Roland and elsewhere. In Roland, each line has a caesura following the tonic accent on syllable 4. If an unaccented terminal syllable follows the tonic accent, the terminal syllable is disregarded; it is not counted in the scansion and is treated thus exactly as such a syllable would be treated at the end of a line. The second line below shows epic caesura and thus an extra, uncounted syllable in the first half-line.

———

[Roland sensed that death held him, It descended from the head to the heart.]

A poem that shows epic caesura will generally show epic caesura in all cases of unaccented syllables at the caesura.2

C.1.3. Lyric Caesura

A lyric caesura is defined as a caesura following an unaccented element that does count in the overall scansion of the line and half-line. To my knowledge, this caesura is only found in decasyllabic verse. The difference between the epic caesura and lyric caesura involves (1) whether the terminal element is counted, and (2) the placement of the tonic accent. In Chanson de Roland, the tonic accent is always on syllable 4. But in decasyllabic lines with lyric caesura, the tonic accent necessarily appears in syllable 3. The following example is from Le Châtelain de Coucy (fourteenth century).

Most poems that show lyric caesura use it infrequently. The two types of caesura, lyric and epic, are generally not found in the same poem.

C.2. Special Problems of the Caesura in Decasyllable

The definitions of caesura types are not controversial, but determining whether an apparent case is metrical, purely stylistic, or even accidental can be problematic. The lyric caesura does not appear regularly in decasyllable verse; and many poems that seem to show evidence of such a caesura might be better analyzed as having, rather than any caesura, an arbitrary (stylistic) pattern of phrasal breaks.

C.2.1. Most decasyllabic lines in French show caesura after syllable 4, and in the classical form, this syllable will also show a tonic accent. Only if the entire poem shows a pattern of regular caesurae can the exceptional lyric caesura be claimed. If the word caesura is used in the description of individual lines, it is merely a stylistic term, not a metrical one. That is, it does not refer to the overall composition of the poem.

C.2.2. Froissart, Flour de la margherite, shows regular (classical) caesura:

Blanche et vermeille, ‖ et par usage habite

en tous vers lieus, ‖ aillours ne se delite.

ossi chier ‖ a le preel d’un hermite,

mes qu’elle y puist ‖ croistre sans opposite.

Note in the first line, the -e of vermeille at the caesura is elided.

C.2.3. Deschamps, in his Ballades, shows an example of lyric caesura:

He! gens d’armes, ‖ aiez en remembrance

vostre pere, ‖ vous estiez si enfant,

le bon Bertran, ‖ qui tant ot de puissance,

qui vous amoit ‖ si amoureusement,

Guesclin prioit . . .

Here, a word break appears without exception after syllable 4, and the invocation of lyric caesura in lines 1 and 2 is surely legitimate.

C.2.4. Machaut, Dit de la harpe:

Phebus, un dieus de moult haute puissance,

avoit la harpe en si grant reverence

que chans nouviaus ja ne li eschapast,

qu’en la harpe ne jouast ne harpast.

par dessus tous instrumens la prisoit

et envers li tous autres desprisoit.

The first three lines could be analyzed as showing regular caesura, preceded by an accent on syllable 4. But despite the word breaks between syllables 4 and 5 in the following lines, it is pointless to speak of caesura here (and clearly incorrect to claim one exists between the definite article li and its noun phrase tous autres in the final line). If one were to cite line 4 as exhibiting lyric caesura following “qu’en la harpe,” one has reduced the caesura from a metrical to a purely stylistic element. These lines have no regular caesura of any kind.

C.2.5. Conventional Accent at Syllable 4

French decasyllables tend to have tonic accent on syllable 4, which leads to an apparent caesura. But this is not the same as a caesura that exists by convention or rule. It is in my view inaccurate in terms of French verse to speak of a flexible caesura or occasional caesura in such cases if these line-structures are produced by accident or, say, by the simple use of common phrases at the beginning of a decasyllable:

Dans les caveaux d’insondable tristesse

Où le Destin m’a déjà relégué;

Où jamais n’entre un rayon rose et gai;

Où, seul avec la Nuit, maussade hôtesse . . .

(Baudelaire, “Un Fantôme”)

The implied caesura in the first three lines is only apparent, as the following line from the same poem indicates:

Je suis comme un peintre qu’un Dieu moqueur

There is clearly no syntactic break between the article un and the noun peintre, and the word break alone does not constitute a caesura.

C.2.6. Italian Variants

The Italian hendecasyllable is defined exactly as is the French decasyllable (sec. B.2.2.1 above). Conventionally, Italian hendecasyllables are said to have an accent on either syllable 4 or 6 along with a flexible caesura. But Italian verse does not show a regular caesura, and it is better to drop this term. To claim that Italian verse has a flexible or movable caesura is to concede that such caesurae exist only in a stylistic and not in a metrical sense.

C.2.7. English Variants

English variants differ from Italian variants in that they are modeled directly upon the French; they do not simply evolve from the same source as French and Italian. Chaucer’s decasyllables are modeled after medieval French decasyllables; more controversially, Pope’s decasyllables are heavily influenced by the rules of classical French Alexandrines. The caesura, regular after syllable 4 in both, is likely a reflection of these sources or a direct allusion to these sources. See below, chapter 6, B.

C.3. The Caesura in the Classical Alexandrine

Classical Alexandrines show caesura following a required tonic accent in syllable 6, and the line itself consists of two hemistiches. Thus the full description of an Alexandrine line is as follows:

![]()

Note that the two halves of the line are not quite the same.

C.3.1. In nearly all periods of French verse, a line could end in an unaccented syllable, that is, a post-tonic syllable. But if a post-tonic syllable were to occur at the caesura (following syllable 4 of a decasyllable or syllable 6 of an Alexandrine), it would have to be accounted for in some way. Theoretically, the post-tonic syllable could count either as one of the required number of syllables (lyric caesura) or as an extra syllable in that position (epic caesura). For the latter, a rule similar to rules in French permitting an extra syllable at the end of a line would need to apply to the caesura.

C.3.2. Classical Solution

Classical Alexandrines generally do not permit epic or lyric caesura. That is, a post-tonic -e can neither count as one of the six syllables required of the first hemistich, nor serve as an extra syllable. But posttonic vowels inevitably appear at the caesura, and the classical solution seems almost desperate.

C.3.2.1. In classical Alexandrines, post-tonic syllables are permitted at the caesura, as they are in medieval verse, but only if elided. If the word preceding the caesura has a post-tonic syllable, that syllable must be elided with the word immediately following the caesura, a word which necessarily must begin with a vowel.

Nous volons au passage ‖ un plaisir clandestin

(Baudelaire, “Au lecteur”)

———

[We steal a clandestine pleasure in passing]

The word passage is permitted in this position because it is followed by a word beginning with a vowel, and the -e is elided. So also:

Dans nos cerveaux ribote ‖ un peuple de Démons.

———

[A demon nation riots in our heads]

The -e in ribote is elided.

C.3.3. Consequences

To most English readers, the rules of the caesura in classical Alexandrines may seem a case of establishing one set of arbitrary rules, then a second set of equally arbitrary rules to eliminate the occasional inconvenient consequences of the first set. Further reflection will show that many common words cannot be used at the caesura. For example, a feminine noun or adjective ending in -es cannot be used because the post-tonic ending (-es) cannot be elided (see sec. A.4 above).

C.4. History of Caesura

C.4.1. One of the most striking of the many changes in French verse in the nineteenth century involves the definition of the caesura. Most histories of French versification state that Victor Hugo changed the conventional structure of the Alexandrine into a three-part (ternary) line. Thus with Hugo the Alexandrine began to show three phrasal units rather than two hemistiches. I mark these implied breaks with a single virgule in the lines below:

Je marcherai / les yeux fixés / sur mes pensées

Sans rien voir au-dehors, sans entendre aucun bruit,

Seul, inconnu, / le dos courbé, / les mains croisés,

Triste, et le jour pour moi sera comme la nuit.

(Hugo, “Demain, dès l’aube à l’heur où blanchit la campagne”)

———

[I will walk, my eyes fixed on my thoughts

Seeing nothing outside, hearing no noise,]

Alone, unknown, my back bent, my hands folded,

Sad, and the day for me will be like the night.]

But in Hugo’s Alexandrines, all ternary lines can also be analyzed as having classical caesura following syllable 6, even though the phrase structure opposes it (e.g., “les yeux ‖ fixés,” “le dos ‖ courbé”):

Je marcherai les yeux ‖ fixés sur mes pensées

Sans rien voir au-dehors, ‖ sans entendre aucun bruit,

Seul, inconnu, le dos ‖ courbé, les mains croisés,

Triste, et le jour pour moi ‖ sera comme la nuit.

This ternary Alexandrine became known as the romantic Alexandrine

C.4.2. A greater challenge to the domination of the Alexandrine was by Verlaine, who wrote lines that looked like Alexandrines according to a completely different (and arbitrary) set of rules: thirteen-syllable lines, eleven-syllable lines, twelve-syllable lines without caesura. These are unlike free verse, in that each is produced according to strict rules (even though Verlaine may have made up those rules in the process of composition). Such artificial rules could produce phrases for which there was no precedent in French verse. An example is Verlaine’s “Langueur,” in twelve-syllable lines with no caesura:

Je suis l’Empire à la fin de la décadence,

Qui regarde passer les grands Barbares blancs

En composant des acrostiches indolents

D’un style d’or où la langueur du soleil danse.

———

[I am the Empire at the end of its decadence,

who watches the great white barbarians pass,

while composing indolent acrostics

in a golden style where the languor of the sun dances.]

D.1. Coupe and Measure

A word currently receiving more use in the study of French metrics is coupe. A coupe is a phrasal break, and in earliest French treatises, this word was used to describe what is now a caesura. In modern manuals, the word is used to define those breaks implied by basic phrase structure. Units bounded by coupes are often called measures. Thus, most Alexandrines will show a caesura dividing two hemistiches, and within each of those hemistiches, a coupe separating two phrasal units, or measures.

D.1.1. When classical Alexandrines are analyzed this way, the coupe is a secondary break, as in the following line of Rousseau analyzed by Mazaleyrat (p. 15):

Rien n’y garde / une form(e) ‖ constante / et arrêté

In this case, one must define the caesura as the basic structural break, the coupe as a supplemental break. In the above line, the caesura defines two hemistiches; a coupe within each hemistich defines one as 4/2, the other as 3/3.

D.1.2. When the word coupe is used to indicate the phrasal structure of romantic and modern French verse, its relation to the caesura is less clear, as in the line from Hugo quoted above:

Je marcherai / les yeux fixés / sur mes pensées.

The two coupes here are used to define the basic three-part structure of the line. The caesura (between yeux and fixés) is not part of the basic line structure. In other lines, the caesura is in fact part of the basic structure. Mazaleyrat (p. 20) analyzes lines from Apollinaire’s “d’Alcoöls” as follows:

S’étendant / sur les côtés / du cimetière

La maison / des morts // l’encadrait / comme un cloître.

———

[Extending over the sides of the cemetery

The house of the dead frames it like a cloister.]

In this case, I assume the implied caesura in line 2 is considered part of the phrase structure, and Mazaleyrat considers the basic structure of these lines as 3 / 4 / 4 and 3/2 // 3/3.

D.2. Rhythm

What is called the rhythm of a French line, however defined, is a function of the accents and phrasal units that form measures whose boundaries are defined as coupes. So considered, rhythm is directly related to the analysis by measure or coupe. No doubt these features are self-consciously used by French poets, but they belong, in my view, to the realm of stylistics rather than metrics. That is, the placement of a phrasal coupe is not something required by rules of versification, but something preferred by considerations of style. Georges Lote has pointed out that there is no mention of accent or its relation to rhythm in any commentary on French verse before the eighteenth century.

D.3. Enjambment (Rejet/contre-rejet)

Classical Alexandrines generally form autonomous syntactic units corresponding to each line. Where they do not, one speaks of enjambment. Most metricians consider the elements known as rejet and contre-rejet as two special cases of enjambment. The following two examples, shown here in italics, should suffice (both examples from Mazaleyrat, pp. 120–23):

C’est ici que l’amour, la grâce, la beauté,

La jeunesse ont fixé leurs demeures fidèles.

(Chénier, “Fragments d’élegies,” XXI)

———

[It is here that love, grace, beauty,

and youth have fixed their faithful homes.]

La jeunesse, which belongs to the preceding syntactic phrase, is characterized as the rejet.

Plus loin, des ifs taillés en triangle. La lune

D’un soir d’été sur tout cela.

(Verlaine, “Nuit de Walpurgis classique”)

———

[Further off, the yews cut in a triangle.

The moon of a summer evening over all.]

La lune, which belongs to the following phrase, is characterized as the contre-rejet. These features may be more a matter of stylistics than metrics.

Assonance is only a metrical matter in early medieval verse, specifically the chansons de geste, which are written in stanzas called laisses. The final syllable in each line of a laisse must have the same vowel sound, and lines are thus organized by such assonance rather than rhyme.

ço dist li quens “or sai jo veirement

que hoi murrum par le mien escïent.

ferez! Franceis, car jol vus recumenz.”

dist Oliviers: “dehet ait li plus lenz!”

(Chanson de Roland)

The italicized terminations are linked by the nasalized -e, which constitutes the assonance (such sounds as -ent and -enz do not properly rhyme).

As vus Rollant sur sun cheval pasmet,

e Olivers ki est a mort naffrez. . . .

si li demandet dulcement e suëf

“sire cumpain, faites le vos de gred? . . .”

The lines are linked by terminal assonance on -e-.

In general, rhyme involves the repetition of a terminal sound, but this must be defined conventionally.

F.1. Rich, Sufficient, Poor

Most histories of French verse acknowledge a hierarchy of rhyme types involving increasingly complex rhymes. In its basic form, the minimally accepted rhyme is called a sufficient rhyme. This generally is defined as a terminal tonic vowel and preceding consonant. Anything less than a sufficient rhyme (say, a rhyme involving a consonant and unaccented vowel, or a rhyme involving only the terminal tonic vowel) is classified as poor. A rich rhyme might be defined as one involving more than what is required for a sufficient rhyme. A simplified definition of this hierarchy is: one homophone—poor rhyme; two homophones—sufficient rhyme; three homophones—rich rhyme.

F.1.1. Rich rhyme is conventionally obligatory when sufficient rhyme is formed by endings of frequent occurrence, for example, -ue, -er(s), or for words ending in such endings as -eux or -eur. In cases where one of the words in such a rhyme pair is monosyllabic, the rhyme is generally acceptable and considered sufficient: humeur/peur. Examples of various rhyme types in Baudelaire’s “Au lecteur”: sufficient rhymes: lices/vices; cris/débris; rich rhyme: immonde/le monde.

F.1.2. Rhymes that are more complex than this would be called “over-curious” (so DuBellay), or sometimes “leonine” (the term is also used of internal rhymes in the first hemistich of an Alexandrine). Ménades/ sérénades from Hugo’s “Navarin” is an example.

F.2. Acceptable Rhyme Types

A rhyme is determined in part grammatically, in part by ear, and in part by convention.

F.2.1. A short vowel cannot be rhymed with a long vowel; but the first person future of a verb ending in -er (-ai) can rhyme with -é; and some diphthongs can rhyme with simple elements: livre/suivre. Words that have different syllable counts due to technicalities of verse rules can also rhyme, e.g., biens/liens (see sec. A.3.2.1 above; biens, from Latin bene, is monosyllabic; liens, from Latin ligare, is disyllabic).

F.2.2. Examples include parole/folle or sain/tien. Terminal -s, -z, and -x are considered equivalent. The acceptability of such rhymes in early verse depends on whether they are pronounced the same in liaison, that is, when followed by a word with an initial vowel. Thus nous/loups is acceptable; nous/loup is not (see Kastner, pp. 41–43).

F.3. Examples

Examples of the above rhyme types can be found in any classical or romantic French poem. Malherbe, “Dessein de quitter une dame”: incertaine/peine; plus je prise/ma prise (same sound, different grammatical function); l’effet/défait. Baudelaire, “Au lecteur”: corps/remords; lâches/taches; serpents/rampants; involontaire/mon frère.

F.4. Basic Rhyme Pairs

The basic patterns of rhyme pairs are rhymes plates (aabb), rhymes croisés (abab), and rhymes emboités (abba). These are familiar to any English reader of sonnets, where the rhymes of quatrains show all three forms.

F.4.1. In such rhyme pairs, most French verse requires the alternation of masculine rhymes (with a terminal tonic accent) and feminine rhymes (with a post-tonic element).

The formes fixes were a staple of earlier manuals on versification but receive less emphasis in recent ones. They are in origin medieval musical forms. Forms of the rondeau appear in various genres, including late-medieval religious plays. French fixed forms were revived in the late nineteenth century, both in France and in England, and curiously, many of the revived English variants are more rigid than the French. Some of the more important fixed forms are given below.

G.1. Sonnet

French sonnets are in fourteen lines, generally Alexandrines. The major French form has two quatrains (abba or abab) followed by two three-line stanzas (these can be rhymed variously: cdc dee, cdd cee, ccd ede, etc.)

G.2. Ballade

The late medieval form of the ballade found in the work of Deschamps consists of three eight-line stanzas in decasyllables, rhymed ababbcbc, followed by a shorter envoy. Villon’s “Ballade des pendus” is in ten-line stanzas with a five-line envoy. The “Ballade de Villon a s’amye” (with his name in acrostics) is in eight-line stanzas. Examples of the ballade also occur in octosyllables.

G.3. Rondeau

A rondeau involves the repetition of a two-line refrain. The basic medieval form is as follows (the refrain is represented with AB, rhymes in a and b):

A Quant j’ay ouy le tabourin

B Sonner pour s’en aler au may

b En mon lit fait n’en ay effray

a Ne levé mon chef du coissin

a En disant: “Il est trop matin

b Ung peu je me rendormiray,”

A Quant j’ay ouy le tabourin

a Jeunes gens partent leur butin!

b De Nonchaloir m’acointeray,

b A lui je m’abutineray:

a Trouvé l’ay plus prochain voisin.

A Quant j’ay ouy le tabourin

B Sonner pour s’en aler au may.

(Charles d’Orleans)

———

[When I hear the drum / sound to rise in May, / In my bed, I am not afraid, / nor do I raise my head from the pillow, / Saying: It is too early; / I will doze a bit more, / when I hear the drum. / Young people share their booty! / I know Indifference. / I will share with him. / I have found him my nearest neighbor. / When I hear the drum / sound to rise in May.]

G.3.1. Among many variants is the rondeau redoublé, whereby each of the four lines in the opening stanza is repeated as a refrain in the four following stanzas (a modern version is Theodore de Banville’s “Rondeau Recoublé, à Silvie”).

G.4. Virelai

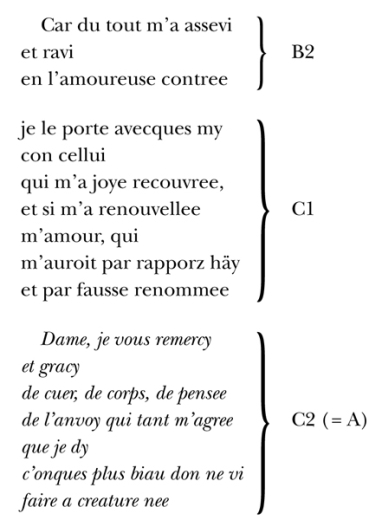

Unlike the sonnet (sec. G.1 above) and the villanelle (sec. G.5 below), the virelai was not revived after the Middle Ages. It is a poem consisting of two or three stanzas of what is called the bergerette, a form of the rondeau, with the refrain repeated in its entirety. The virelai begins with a refrain of several lines, and this refrain closes each stanza. The abstract form is as follows:

Refrain (A)

Stanza I: B (B1 and B2)

C (C1 and C2 [C2 = A])

Stanza II: B

C

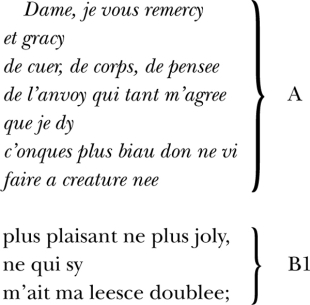

The following example is from Deschamps, “Virelay”:

G.5. Villanelle

The medieval villanelle enjoyed a resurgence in the nineteenth century and assumed a more rigid form, particularly and strangely among English writers. In its strictest form, it is nineteen lines of three-line units, with an intercalated, two-line rhyming refrain (represented in the following schema by A1 and A2, in italics). Among many English versions is Dylan Thomas’s “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night.”

A1 Do not go gentle into that good night;

b Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

A2 Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

a Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

b Because their words had forked no lightning they

A1 Do not go gentle into that good night.

a Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

b Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

A2 Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

a Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

b And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

A1 Do not go gentle into that good night.

a Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

b Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

A2 Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

a And you, my father, there on the sad height,

b Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

A1 Do not go gentle into that good night.

A2 Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Note that the syntax of the refrain changes, although the sound and orthography do not.

Texts: Text of Baudelaire is from Oxford World’s Classics, Oxford Univ. Press, 1993; early medieval works from Karl Bartsch, Chrestomathie de l’ancien français (viiie–xve siècles) (1866; 12th ed., New York: Hafner, 1951). Modern French examples are from Pléiade editions: Anthologie de la poésie française (Moyen Age, xvie siècle, xvie siècle); and Anthologie de la poésie française (xviie siècle, xixe siècle, xxe siècle) (Paris: Gallimard, 2000); all translations are mine.

References: Benoît de Cornulier, Art poëtique: notions et problèmes de métrique (Lyons: Presses Universitaires de Lyon, 1995); W. Theodor Elwert, Traité de versification française des origines à nos jours (Paris: Klincksieck, 1965; trans. of Französische Metrik, 1961); L. E. Kastner, A History of French Versification (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1903); Georges Lote, Histoire du vers français, 3 vols. (Paris: Boivin, 1949); Jean Mazaleyrat, Elements de métrique française (Paris: Armand-Colin, 1974); Warner Forrest Patterson, Three Centuries of French Poetic Theory: A Critical History of the Chief Arts of Poetry in France (1328–1630) (Ann Arbor: Univ. of Michigan Press, 1935); Clive Scott, French Verse-art: A Study (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1980).

1. The definition of a syllable is defended vigorously by Mazaleyrat, who notes (1) verse is based legitimately on “illusions” rather than phonetic realities and (2) the classical definition of syllable permits a balance between consonant and vowel, one represented by the spelling of early French. The evolution of the language, involving the dropping of unstressed, post-tonic vowels, for example, reduces this balance by emphasizing the consonants. See Mazaleyrat, pp. 31–36.

2. It is inconvenient to speak of the post-tonic syllable as syllable 5, since the basic structure of each line has a second tonic accent at what I call syllable 10. Therefore, I continue to speak of the initial syllable following the caesura in such lines as syllable 5.