Accentual Verse

Old English

A. Basic Linguistic Principles

B. Standard Descriptions of Verse

The third system of versification we will deal with is accentual verse, also known as “tonic” verse. As is the case with isosyllabic verse, little if any historical verse is purely accentual: all European verse described as accentual has basic or secondary rules regarding syllable number or even syllable length. Thus the standard distinction between English verse as “accentual-syllabic” and early Germanic verse as “accentual” is misleading. I take as a model Old English verse (700–1100). The principles outlined here can be applied to other early Germanic verse such as Old Norse; later forms of medieval Germanic verse including Middle English verse show only traces of these early systems.1

A. Basic Linguistic Principles

Most scholars agree on the basic constitutive elements of early Germanic verse:

a) syllable count and syllable length

b) word accent

c) alliteration

A.1. Vowel and Syllable Length

As in Latin, syllables in Old English are distinguished linguistically as long or short in quantity. A syllable is considered long metrically if (1) it contains a naturally long vowel, or (2) it is followed by particular consonant combinations. Also as in Latin, the combination of a short, accented syllable followed by a second syllable can be considered a resolved long; that is, it is metrically equivalent to one long syllable. Vowel quantities can be determined etymologically; and in some cases they can be determined, through somewhat circular reasoning, by the use of such vowels in poetry.

A.1.1. Modern dictionaries and editions of Old English generally mark long vowels. Old English manuscripts themselves, however, do not, and recent editorial and scholarly transcriptions have tended to follow this practice. I mark them in my transcriptions here, although the meter of Old English is perfectly intelligible without knowledge of these vowel quantities.

A.1.2. Diphthongs

Old English diphthongs, like single vowels, are also distinguished linguistically as long or short. Among the more common diphthongs are eo, ea, and ie. The conventional way of marking a long diphthong in modern transcriptions is with a macron over the first element. Thus in the word fēond, ēo is a long diphthong in a single, metrically long syllable. In heofon, eo is a short diphthong, and the syllable in which it appears is metrically short.

A.2. Accent

Germanic word accent is “regressive”—that is, it has moved backward from its position in proto-Germanic, the hypothesized ancestor of modern Germanic languages. In all recorded Germanic languages, this accent falls on the root syllable (the first syllable of a word unless the first syllable is a common prefix). Thus, in the following passage from “The Wanderer,” multisyllabic words have their accent on the first syllable: SIG-on; SUM-e; AN-geald, etc. The root syllable of ge-LAMP is the second syllable:

sigon þā to slǣpe. Sume sāre angeald

ǣfonræste, swā him ful oft gelamp.

Prefixes that do not receive a word accent in multisyllabic words are easily recognized, often simply by their modern English cognates. For example, bi-dǣled; other examples of words with common, unaccented prefixes are ge-bīdeð, ge-myndig, ā-secgan (all from “The Wanderer”).

A.2.1. Compound Words

Many early Germanic words are compounds, that is, single words formed of combinations of substantives: noun/noun, adjective/noun, noun/gerund, etc. Compound words formed of independent word elements have a primary accent on the root syllable of the first word element; the second word element retains its accent as a secondary accent: the compound word lagu-lāde (sea-way) thus has a primary accent on la- in lagu, and a secondary accent on the first syllable of -lāde. Other examples from “The Wanderer” are mōd-cearig, mōd-sefan, ferð-locan (which I will somewhat desperately translate as “spirit-caring,” “spirit-heart,” and “spirit-locker”). The secondary accent can partake of the metrical structure of some half-lines; in others, it is apparently disregarded.

A.3. Alliteration

Germanic verse is organized in large part by alliteration, that is, the repetition of the first stressed consonant or vowel sound in a word. The importance of such alliteration is clearly related to the regressive nature of the Germanic word accent, although both the development of Germanic verse and the movement of the accent occurred before written records exist. The alliterating element in a compound word is always on the root syllable of the first word element. These alliterations are generally evident in the transcription of any early Germanic line:

Warað hine wræclāst, nales wunden gold,

ferðloca frēorig, nalæs foldan blǣd.

(“The Wanderer”)

In these lines, the alliteration is on w in line 1 and f in line 2.

A.3.1. A curious feature of early Germanic verse is that all initial vowels are considered metrically acceptable alliterations. This is likely due to the fact that in the earliest Germanic verse each word root consisted of the form CVC (consonant-vowel-consonant). Words with initial vowel are the result of the loss of a consonant in proto-Germanic. These words traditionally alliterated with that consonant and continued to do so after it was lost. Thus, in “The Wanderer,” line 8:

Oft ic sceolde āna uhtna gehwylce

The alliterating words are āna, and uhtna, and likely Oft.

A.3.2. Consonant Combinations

In general, alliterations involve only a single consonant; w- alliterates with w-, wl-, and wr-; d- with d- and dr-, etc. Poems occasionally give apparent (but illusory) evidence that more than the initial element is involved (e.g., hr- in “The Seafarer,” line 32, and “The Wanderer,” line 77, cf. line 72). Exceptional is the consonant s: st- alliterates only with st-; sc- only with sc-; and s- only with s + vowel or s + -n- (“The Wanderer,” lines 93, 101).

B. Standard Descriptions of Verse

Standard descriptions of Latin and French verse are based on the theories and terminology of contemporary or near-contemporary writers for whom these were living languages. Early Germanic languages, by contrast, were not living languages for those who developed what are now the standard descriptions of its verse; the earliest description of Icelandic verse is by the thirteenth-century saga writer and historian Snorri Sturluson, who admits that the earlier poets may not have followed his prescriptions. Old English poems were unknown to English readers until the late sixteenth century; Beowulf was unknown until the late eighteenth century. Scholarship on Old English verse begins in the seventeenth century; it is thus historical and largely descriptive. My account below is based on what became the standard description of this verse in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

B.1. Basic Line Structure

Manuscripts of Old English do not represent verse line structure by writing on successive lines. The only indication of lines and half-lines are raised dots between these units. In some of the earliest printed editions of Old English verses from the nineteenth century, the line unit is the half-line; in twentieth-century transcriptions, the basic line unit that is represented typographically is the complete line, consisting of two half-lines with a space between them.

B.1.1. Old English verse is constructed in pairs of half-lines joined by alliteration. A normal half-line contains two prominent accented syllables; the potentially alliterating elements are the initial consonants or vowels of these accented syllables. These accented syllables must contain a long syllable or the equivalent of a long syllable. In the second half-line, the first principal accent must partake in the line’s alliteration. In the first half-line, either or both of the accented syllables must alliterate.2

B.1.2. Alliterating elements must be the principal word elements in any half-line, that is, nouns, adjectives, principal verbs, and stressed adverbs. Prepositions, pronouns, and auxiliary verbs are metrically unstressed.

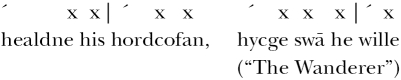

B.1.3. The words arsis and thesis are unavoidable here: in descriptions by late-nineteenth-century German philologists, each half-line consists of two feet, measures, or metra. In each foot, the accented, alliterating element is the arsis (Hebung, translated variously as “lift” or “rise”); the unaccented elements form the thesis (Senkung, “sinking,” or “dip”).3 In the second foot of the first half-line above, the arsis is hord-; the thesis is -cofan. For certain common line types, these terms pose no difficulty: the above line shows two half-lines, each with two easily recognized “stresses” or “lifts” (arses) and two corresponding “dips” or unstressed elements (theses); these form two feet. But not all half-line types consist of symmetrical measures or feet.

B.2. Eduard Sievers’s System

The most important attempt to categorize Germanic verse types was by Eduard Sievers in the late nineteenth century. Sievers’s system is purely descriptive and taxonomic. It distinguishes half-line types by certain rhythmic patterns. It does not imply that these half-line types are foundational; that is, they do not generate verse types nor were they known and consciously deployed by the poets themselves. Even scholars who reject Sievers’s terminology assume their readers understand the basic components of this system.

B.2.1. Half-line Types

There are five basic half-line types in Sievers’s system, labelled A–E. Each verse or half-line consists of two feet or metra, and the units that make up a foot are called Glieder (sing. Glied, “member” or “limb”). Basic half-line types have four Glieder. The basic A-type verse or halfline has, in Sievers’s system, two feet of two Glieder. Many transcriptions of Sievers’s system use a form of the notation shown in section B.1.1 above, whereby accented elements are marked with an acute accent (´), secondary accents are marked with a grave accent (ˋ), and unaccented syllables are marked with an x. This form of notation is useful in analyzing individual lines. But to show basic patterns, I have modified it slightly, and in my representation below, X represents an accented long syllable or its equivalent; x represents a variable number of unaccented syllables; S represents a syllable with a secondary accent. In the simplest line, each Glied is equivalent to a syllable; but for most lines, the unstressed element (x) consists of more than one syllable. What are conventionally regarded as Sievers’s five types of half-lines are as follows:4

A-type: X x | X x

B-type: x X | x X

C-type: x X | X x

D-type:

D1 X | X S x

D2 X | X x S

E-type: X S x | X

In D and E types, the vertical line represents a word break (or the break between the word elements of a compound word) and a hypothesized foot break. In D-type half-lines, the first foot contains a single accented syllable or its equivalent; in E-type half-lines, the final foot consists of a single accented syllable. Thus, for D1: fold-buenda; wadan wrœclastas. D2-type half-lines have a terminal accent and often consist of three words (e.g., eald enta geweorc). E-type half-lines end in an accented monosyllable but are otherwise formally close to D2 types: XS(x) X: orhfulne sīð; ginfœste gife; blǣdfastne beorn (these examples from Beowulf). The opening lines of “The Wanderer” are as follows:

B.2.1.1. Some verse types are complicated by a feature called anacrusis, or extra-metrical syllables preceding the half-line type. Thus, an A-verse can take the form x | X x | X x: gecunnod on cēole (Beowulf, line 5).

B.2.2. Hypermetric Lines

In addition to the regular lines described above, Old English verse contains what are called hypermetric lines. These lines are longer than the lines defined in Sievers’s system and are perhaps expansions of them through the addition of an extra metron. They appear often in religious verse (“The Dream of the Rood”; “Judith”) and in what are called the gnomic sections of more traditional verse, such as in “The Seafarer,” or as here, in “The Wanderer”:

Swā cwæð snottor on mōde, gesæt him sundor æt rūne.

Til bið sē þe his trēowe gehealdeð: ne sceal nǣfre his torn tō rycene

beorn of his brēostum ācǣþan

———

[Thus the wise man spoke in his mind; he sat apart in thought. Blessed be the man who keeps his pledges; nor is too quick to make his anger known]

Hypermetric lines can be seen as variants of Sievers’s half-line types; in the second line above, introductory phrases are added to the basic alliterating half-lines: trēowe gehealdeð and torn tō rycene (both of type A).

B.3. Critiques of Sievers

Sievers’s system has been much criticized. His verse types are not evenly distributed, and there seems to be no rationale in his analysis to explain, say, the rarity of B half-lines, or to deny theoretical combinations such as X x x X, combinations that do occur in modern versions of these lines (for example, in Ezra Pound’s translation of “The Seafarer”).

B.3.1. In The Meter and Melody of Beowulf (1974), Thomas Cable addresses some of these issues by considering Sievers’s half-line types in terms of rising or falling stress, that is, the relative stress between adjoining elements. Cable hypothesizes a rule whereby, in adjoining stressed elements, the second element always receives a lesser stress; but half-lines with adjoining unstressed Glieder are forbidden. Cable’s representation of Sievers’s system is as follows:

A: 1 \ 2 / 3 \ 4

B: 1 / 2 \ 3 / 4

C: 1 / 2 \ 3 \ 4

D1: 1 \ 2 \ 3 \ 4

D2/E: 1 \ 2 \ 3 / 4

Cable’s rule thus allows for only five forms that are mathematically possible by simply combining stressed and unstressed Glieder, and these are in fact the five forms that appear in actual Old English verse.

B.3.2. Whereas Cable retains Sievers’s types as a framework, other scholars, such as Geoffrey Russom, do away with Sievers’s system altogether, criticizing it for failing to deal with basic issues of syntax and word structure. In Old English Meter and Linguistic Theory (1987), Russom reconceptualizes the minimal units of half-line structure, which are no longer formal and abstract (units that look like classical iambs or trochees). What Russom calls “foot patterns” are constructed of three basic linguistic elements: x is an unstressed element; S a fully stressed element; s of secondary stress. Acceptable foot patterns include many familiar from Sievers (Sx: dryhten; Ss: saemann). But many of Sievers’s basic feet (xS) Russom rejects. In Russom’s notation, Sievers’s B half-lines are analyzed x/Sxs or x/Sxxs; C half-lines as x/Sxx or x/Ssx, with foot breaks corresponding to word breaks.

C.1. Andreas Heusler

In his Deutsche Versgeschichte (1925–29), Andreas Heusler criticizes Sievers’s system as mere “Augenphilology” (philology for the eye), arguing instead for a rhythm-based system based on musical measures (Takte). This system was developed by H. Möller in the nineteenth century and much criticized by Sievers himself. In Heusler’s transcription, each half-line has a “ground-form” of two measures of quarter notes in 4/4 time, with possible extra-metrical elements preceding them. Heusler represents this ground-form as follows:

![]()

In each measure, there are two beats: a full stress on the first element, and a secondary stress on the third. A standard A-verse (e.g., gomban gyldan) would be analyzed as two measures, each consisting of an accented half note, a quarter note, and a quarter rest. The deployment of rests and Heusler’s use of four types of accents (single and double forms of acute and grave) become more complex with other line types (examples from Caedmon’s hymn in Heusler, 1:143–44; Heusler’s explanation, 1:33–34).

C.2.J.C. Pope

In The Rhythm of Beowulf (1942), J. C. Pope took this musically based theory further, translating Heusler’s often eccentric notation back into musical notation and exploiting the idea that Old English verse was accompanied by the harp. To Pope, the musical analogy is not metaphorical; Pope even criticizes Heusler’s 4/4 tempo as too slow (a tempo Heusler chooses only for convenience) and instead uses 4/8 as the basic time signature.

C.2.1. In Pope’s description, the harp alternates heavy and light strikes; each measure (half-line) has one primary strike of the harp and one secondary one, and the strike must always be on the first element of a measure. In A-type half-lines the heavy harp strikes coincide with the two main accents. But in B- and C-type half-lines, a harp strike precedes the initial unstressed elements; the arsis, or stressed element, of the first measure consists of a rest (no words) followed by an unstressed syllable or syllables forming the “dip,” or thesis. Thus in my notation, B and C half-lines might be divided (as divided in Heusler and later in Russom) as follows:

B: .x | X x S

C: .x | X S x

Pope’s musical analysis of such verses on pp. 164–65 is as follows:

B-verse: syððan ǣrest wearð (Beowulf, line 6)

![]()

C-verse: ofer hronrāde (Beowulf, line 10)

![]()

In these scansions, as in Heusler’s, the verse accent (ictus) is not represented in the written words themselves; furthermore, Pope’s scansions disregard syllable length, which would seem essential to any description that involves musical notation.

C.3. Limitations

The hypotheses of Pope and Heusler are compelling, but they may have little to do with Old English verse composition. We have no idea how Old English verse was composed apart from the mythical story in Bede regarding the illiterate poet Caedmon (where there is no mention of a harp) and little specific evidence of how it was performed other than allusions to the harp accompaniment in poems such as Beowulf. The descriptions by Heusler and Pope work because they use a flexible system of notation—classical musical notation—one that has proven to be useful in describing music much different from that which it was originally meant to describe. German philologists often used this terminology metaphorically. Pope seems to literalize it, and even uses his own contemporary performance (see pp. 38–39) as evidence not only of the relation between half-lines but of the actual historical method of performance that underlies the text.

D.1. Old Norse and Old Saxon

The earliest Germanic poetry contemporary with Old English can be analyzed according to Sievers’s system.

D.1.1. Old-Saxon Heliand (ninth century):

D.1.2. The following Old Norse selection is nearly contemporary:

Later Old Norse poetry (Skaldic poetry) develops other more elaborate verse forms that will not concern us here.

D.2. Later Medieval German Variants

D.2.1. Later Germanic verse, particularly when it includes the same thematic material found in Old Norse verse, incorporates at least some of the principles of earlier Germanic verse. The following from the twelfth-century Nibelungenlied is written in four-line rhymed stanzas:

Es wuohs in Búrgónden ein vil édel magedin,

daz in allen landen nicht schoeners mochte sîn,

Kriemhilt geheizen: si wart ein scoene wîp

dar umbe muosen degene vil verlîesén den lîp

The stanza consists of four lines formed of two half-lines, conventionally called the a-verse and b-verse. B-verses show masculine end-rhymes in the pattern aabb. A-verses show feminine rhymes in the same pattern. Standard accounts in literary histories describe these half-lines as accentual. Each half-line consists of three “lifts”; the final half-line (4b) consists of four “lifts.” (In Heusler’s account, each is a modification of a four-stress “ground-form.”) If this account is accurate, stresses may be rhetorical rather than linguistic; they are determined not by the particular meaning of a line but rather by how that meaning might be expressed in performance. Exactly where such stresses are to be placed may not be always obvious to non-native speakers of Old High German.

D.2.2. By contrast, Gottfried von Strassburg’s Tristan (twelfth century) clearly imitates the octosyllabic verse used in French chivalric romances and can be usefully described in the terms familiar to most English speakers: here iambic tetrameter—four feet of iambs, defined by stress—x ´ x ´ x ´ x ´:

Gedaht man in ze guote niht

von den der werlde guot geschicht

so ware ez allez alse niht,

swaz guotes in der werlt geschicht.

There is in this no trace of the earlier Germanic verse seen in the earliest Old Norse poems or in Old English poetry.

D.3. Middle English

D.3.1. The twelfth-century “The Owl and the Nightingale,” in rhymed couplets, may well be analyzable in what has become the standard language used for discussing English verse, that is, in terms of units of feet. It is the first Middle English poem written out in lines rather than as continuous prose in its manuscript:

Ich wes in one sumere dale

In one swithe dyele hale

Iherde ich holde grete tale

An vle and one nyhtegale.

D.3.2. In other early lyric verse, some remnant of alliteration is found but seems to have become more decorative than structural. The metrical basis of the following verse from the thirteenth-century Harley Manuscript 2253 is far from obvious:

Lenten ys come wiþ love to toune,

Wiþ blosmen & wiþ briddes roune,

þat al þis blisse bryngeþ;

Dayes-eʒes in þis dales,

Notes suete of nyhtegales,

Vch foul song singeþ.

These are perhaps octosyllables. Or should we describe these lines as having four required stresses where two must alliterate? Is this the combination of two or more distinct metrical systems, for example, accentual-alliterative and rhyming? Or is one of these apparent systems purely secondary and ornamental?

D.3.3. Verse of the Alliterative Revival

The clearest analog to early Germanic verse occurs in the so-called alliterative revival of the fourteenth-century, for example, in William Langland’s Piers Plowman and the poems of the Pearl manuscript. This verse, however, cannot be analyzed according to the principles used in early Germanic verse, and obviously, more than stress and alliteration is involved in its composition. Some poems incorporate elaborate rhyming stanzas (Pearl); for others, the rules for composition involve considerations of alliteration, syllable count, and accent. But the precise rules remain controversial, and only in extreme cases could one say a line fails to meet such rules. Although it is not obvious what the metrical rules for these lines might be, some of the general features of older Germanic verse apply:

In a somer seson, whan softe was the sonne,

I shoop me into shroudes as I a sheep were,

In habite as an heremite unholy of werkes,

Wente wide in this world wondres to here.

(Langland, Piers Plowman)

The two half-lines are not equivalent, and the first half-line contains more alliteration than the second half-line. In addition, in these lines the metrical stresses are likely not the same as linguistic stresses, whatever the rules for their production might be.

D.4. Modern Variants

Remnants of early alliterative verse structure or allusions to it can be found in modern verse:

Dem Schnee, dem Regen, dem Wind entgegen,

Im Dampf der Klüfte, durch Nebeldüfte,

Immer zu! immer zu! ohne Rast und Ruh.

Lieber durch Leiden wollt ich mich schlagen,

Als so viel Freuden des Lebens ertragen.

Alle das Neigen von Herzen zu herzen,

Ach, wie so eigen schaffet es Schmerzen

Wie, soll ich fliehn? Wälderwärts ziehn?

Alles, alles vergebens!

Krone des Lebens, Glück ohne Ruh,

Liebe bist du, o Liebe bist du.

(Goethe, Rastlose Liebe [1815; transcription F. Schubert])

This verse by Goethe could be described in the classical language of feet and foot types. Yet classical foot-based metrics seems to fail here, just as surely as it does when confronting Hamlet’s “To be or not to be.” The Goethe poem follows or implies a musical form (as Schubert’s musical setting, from which it is transcribed, suggests). But the half-line structure, alliteration, and stress patterns seem related as well to early Germanic verse types. There are numerous other variants in modern verse, most obviously, Gerard Manley Hopkins’s sprung rhythm, which I discuss in chapter 6.

Texts: Old English texts from Frederic G. Cassidy and Richard N. Ringler, Bright’s Old English Grammar and Reader, 3rd. ed. (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1971) and Friedrich Klaeber, Beowulf and the Fight at Finnsburg, 3rd ed. (Lexington: D. C. Heath, 1950). Middle English texts adapted from O. F. Emerson, A Middle English Reader (New York: Macmillan, 1905) and Richard Morris and W.W. Skeat, Specimens of Early English (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1873); early Germanic texts adapted from Friedrich v. der Leyen, Deutsch Dichtung des Mittelalters (Frankfurt-am-Main: Insel, 1962).

References: Thomas Cable, The Meter and Melody of Beowulf (Urbana: Univ. of Illinois Press, 1974); Andreas Heusler, Deutsche Versgeschichte mit Einschluss des altenglischen und altnordischen Stabreimverses, 3 vols. (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1925––29); Winfred P. Lehmann, The Development of Germanic Verse Form (Austin: Univ. of Texas Press, 1956); John Collins Pope, The Rhythm of Beowulf: An Interpretation of the Normal and Hypermetric Verse-Forms in Old English Poetry (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 1942) and “Old English Versification,” in Eight Old English Poems, 3rd ed., ed. J. C. Pope, pp. 129–58 (New York: W.W. Norton, 2001); Geoffrey Russom, Old English Meter and Linguistic Theory (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1987); Eduard Sievers, Altgermanische Metrik (Halle: Niemeyer, 1893).

1. Note on special characters: ð and þ are alternate ways of representing th; æ is a simple vowel, not a diphthong, and it can be long or short. Some transcriptions distinguish pure vowels from open variants with a cedilla, but that distinction has no bearing on meter and is not made here. Ʒ (yogh) is a special consonant representing several sounds in Old English; it can be conventionally transcribed as the letter g.

2. For my modifications of this conventional system of notation, see sec. B.2.1 below.

3. The German words are unambiguous, although the classical terms they translate (arsis and thesis) are not (see chap. 2, B.3.2 and note 3). For German, the late-Latin use of the terms is more convenient; the Hebung (= arsis) corresponds roughly to the verse accent (ictus) in classical verse.

4. Although Sievers does define two D-type half-lines in this fashion, his own numbering and classification of D-lines differs from the conventional representation I reproduce here; see Altgermanische Metrik, pp. 31 and 34.