Implications for the Study of English Verse

Four Studies

A. English Versions of Quantitative Verse

B. Syllabic and Isosyllabic Verse Forms

C. Accentual Verse: Sprung Rhythm

A. English Versions of Quantitative Verse

The attempts of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century English poets to write verse according to the principles of quantity are well known, and several essays devoted to the topic were printed in the classic anthology of G. Gregory Smith, Elizabethan Critical Essays (1904). These efforts are generally dismissed as failures, as if there were something unnatural and perverse about the attempt to import foreign metrics into English or to force English to conform to non-English rules. But disparaging these attempts does little to clarify them. To introduce principles of quantity is no more or less disruptive of native English versification systems than to introduce versions of classical genres: comedy, tragedy, epic, etc.

A.1. Alternatives

There are three ways in which classical meters could be applied to English:

a) Classical prosodic rules could be imposed directly. English syllables would thus be defined as long or short the same way Latin syllables might be defined as long or short and verse forms written according to these quantities. Thus, the word dying would be scanned not as a trochee (´ x), that is, one stressed syllable followed by an unstressed syllable, but rather as a iamb (˘ _), that is, one short syllable followed by one long syllable.

b) The distinction of long/short syllables in quantitative verse could be translated into a binary system of stress; that is, English stress would be the English prosodic equivalent of Latin quantity. Thus, the English version of a Latin dactyl (_ ˘ ˘) would be ´ x x—one stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables; the word dying would be scanned as a trochee (one stressed syllable followed by an unstressed syllable). Longfellow’s Evangeline is one of the most often cited examples of a poem written according to these principles.

c) A presumably native English equivalent could be substituted for a classical verse type. Milton thus writes Paradise Lost in what is known as blank verse, an English form that to Milton was analogous to the dactylic hexameter used in Homer and in Vergil, even though the two have little formal or prosodic relation.

A.2. Relation between Accentual and Quantitative Verse

For the modern reader and modern poet of English verse, foreign meter is interesting and useful insofar as it differs from what is thought to be ordinary English meter; a foreign (or arbitrary) verse system might thus be useful in freeing one of tradition (thus Marianne Moore’s isosyllabic verse, or the work I note in chap. 5, E). Suppose one wished to revolutionize limerick writing and do away with the more constraining elements of tradition: one could write a limerick according to quantitative rather than accentual principles (see example, chap. 2, B.4, note 4). This would force the budding limerick writer to reimagine what constitutes a basic verse line. Imposing quantitative verse rules forces a writer into verbal constructions impossible under other systems, and it is the clash of the two systems that is most interesting.

Yet this was certainly not the intention of early modern writers such as Philip Sidney, Gabriel Harvey, and Thomas Campion. These poets wanted to refine English verse, not revolutionize it. That is, they wanted to produce verse in which the two systems—native accented prosody and what they called “reformed” quantitative prosody—could be made to correspond. What they termed “artificial verse,” that is, English verse written according to the principles of Latin verse taught in schools, was to be nearly indistinguishable from English verse constructed according to accents. Because these early modern writers were not interested in exploiting the clash between these systems, it is sometimes difficult to determine which versification principles apply to particular poems.1

A.2.1. What constitutes a long syllable in English is variable, and writers of quantitative verse define such syllables differently. Thus to determine the verse form used by a writer, it is often necessary to proceed not from prosodic considerations to the verse form but rather toward the prosodic considerations that are at the base of a given (or hypothesized) verse form. One indication that a verse is written according to quantity is simply that it will not scan according to patterns of accent.

A.3. Two Forms of Elegiac Couplet

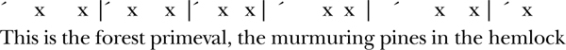

A.3.1. Sidney’s elegiacs are based directly on the classical form:

Unto a caitif wretch, whom long affliction holdeth,

and now fully believ’s help to be quite perished,

Grant yet, grant yet a look, to the last moment of his anguish,

O you (alas so I finde) caus of his onely ruine.

(Arcadia, bk. 3)

The first couplet is a dactylic hexameter followed by the pentameter of a classical elegiac couplet. Both lines can be scanned by quantity and perhaps by accent as well; all syllables that receive a stress accent are also counted long in the quantitative scansion (although some unstressed syllables are counted long). This might be indicated as follows:

The pentameter of the second couplet can only be scanned properly according to quantity:

The accent of “ruine” on the first syllable clashes with the required quantitative scansion, whereby this is an iamb (the first syllable is short, the second long). The lines are thus written in quantitative meter.

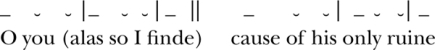

A.3.2. Campion’s version of elegiac couplet is more complex. Campion wished to use lines that he considered natural to English and, like many writers, described natural English rhythm as iambic (it is not entirely clear whether he meant that this iambic rhythm is quantitative or accentual). Campion’s elegiac couplet is composed not of dactylic verse but of two iambic verse types, which he defines as a “licentiate iambick” followed by a line constructed of two “dimeters.”

A.3.2.1. Campion’s “licentiate iambick” is close to what is loosely known as iambic pentameter; his description of this verse is reminiscent of descriptions of the Latin iambic senarius (see chap. 2, F).2 According to Campion, there are three forms of this iambic line, beginning with a basic form:

![]()

In the second form, which Campion calls the “licentiate” form, substitutions are permitted in feet 1, 2, and 4; for the iamb, one can substitute a spondee, tribrach, or dactyl but, as in the Latin senarius, not a trochee (that is, one can substitute a short for a long or resolve any long into two shorts). Anapests, I believe, are permitted in feet 2 and 4 but not 1. Foot 3 and foot 5 must be pure iambs. There is, according to Campion, a break after syllable 4, what Campion calls a “naturall breathing-place.” These possible substitutions might be represented as follows:

In a most tantalizing note, Campion identifies a third form by suggesting that more license is permitted in verse comedy. Such a form would permit free substitution in any of the feet, including 3 and 5, and Campion’s implied forms of “iambick” would be roughly analogous to the forms of iambic senarius in Latin. Unfortunately, Campion gives no examples. Was he thinking of the verse of his contemporary English dramatists?

A.3.2.2. Dimeter. Campion defines a dimeter as a line that consists of two feet plus an extra syllable. The first foot is generally a trochee (a spondee or iamb may be substituted); the second a trochee or tribrach; the last foot “common.” Campion gives the following example:

Raving warre, begot

In the thirstye sands

Of the Lybian Iles,

Wasts our emptye fields

Line 1 in Campion’s analysis likely includes a spondee for foot 1 and is scanned _ _ | _ ˘ | > The opening prepositions in lines 2 and 3 are perhaps “long by position” (a vowel is followed by a consonant combination).

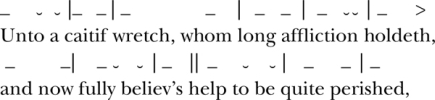

A.3.2.3. Campion’s version of elegiac couplet is thus composed of two problematic line types: a “licentiate iambick” (the second of the three forms of iambic described above in sec. A.3.2.1) followed by a line composed of two dimeters:

Constant to none, but ever false to me

Traitor still to love through thy faint desires

Not hope to pittie now nor vaine redresse

Turns my griefs to teares and renu’d laments.

(Campion, “An Elegy”)

I believe Campion intends this to be scanned as follows:

I frankly could not and would not scan it precisely that way without Campion’s description. As in Sidney, there is almost no conflict of accent and quantity.

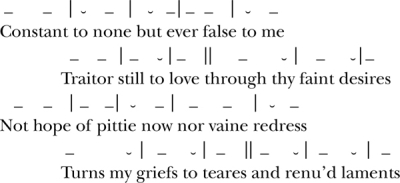

A.4. English Sapphics

For the most part, English writers adopted a generalized form of Aeolic verse in what became known as the Horatian ode—short, four-line, rhymed stanzas written on themes common to the verse of Horace (discussed in chap. 5, B.2.1). Exceptional is the Sapphic. The form is easily imitated visually as a four-line stanza of three repeated lines followed by a shorter concluding line, generally of the form _ ˘ ˘ (quantitative version) or ´ x x (accentual version). The various ways of adapting the form to English are shown below.

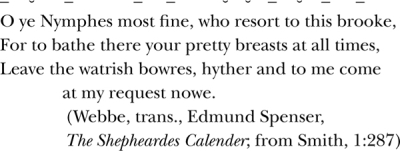

A.4.1. William Webbe (quantitative form):

A.4.2. Algernon Charles Swinburne, “Sapphics” (accentual form):

A.4.3. William Hyde Appleton, trans., “Hymn to Aphrodite” (1893):

Throned in splendor, immortal Aphrodite!

Child of Zeus, Enchantress, I implore thee

Slay me not in this distress and anguish

Lady of beauty.

This last case, I believe in decasyllables, could be called an allusion to the Sapphic stanza in its visual form and in the rhythm of its last line. Many similar examples were probably written as school exercises or in the spirit of school exercises (“Turn the following prose passage into Sapphics . . .”).

B. Syllabic and Isosyllabic Verse Forms

B.1. Heroic Couplet

The following is one of the few cases where my own analysis is not compatible with standard sources on metrics. Since the eighteenth century, histories of English verse have associated the rhymed verse found in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales with the heroic couplet of Dryden and Pope. Such couplets are now generally described as pairs of rhyming lines in iambic pentameter, and the main point of contention in literary histories is whether this tradition is continuous, that is, whether the decasyllabic couplets in the Canterbury Tales are variants of the form used by Dryden and Pope. While the association of Chaucer’s verse with that of Dryden and Pope is reasonable (both Dryden and Pope read and translated Chaucer), the labeling of all this verse as rhymed iambic pentameter is misleading. To Dryden himself, who translated Chaucer into rhyming couplets in 1700, Chaucer’s verses were syllabic: his “Numbers” were occasionally deficient in that they lacked the requisite number of ten syllables a line. This is exactly how Chaucer characterizes his own verse, apologizing in his Hous of Fame for lines that “fail in a syllable.” And whereas some scholars give Chaucer credit for inventing what is now known as the heroic couplet, to Dryden, neither Chaucer nor English poets in general invented anything: “The Genius of our Countrymen being rather to improve an Invention, than to invent themselves” (from Preface, Fables Ancient and Modern, 1700).

B.1.1. The notion of a specifically English tradition here—that is, the idea that Chaucer wrote and perhaps invented a verse form later perfected by Pope, a verse that can be described as both foot-based and accentual—may well misrepresent the principles and bases of both types of verse. This notion begins with the assumption of a basic iambic, accentual form. A better and equally workable definition of this form of couplet is that the couplets of Chaucer and Pope are fundamentally decasyllabic lines written according to principles articulated in French poetics and exemplified in French verse. Chaucer’s and Pope’s couplets are similar not because they have a direct relation but because both are based on the French verse of their near contemporaries. Thus the English decasyllable as found in Chaucer and Pope can be described in the same notation used for French decasyllables of any period:

![]()

Chaucer, far from the inventor of heroic couplet, simply copies the French decasyllable, with the rhymes plates one finds in octosyllabic narrative. The iambic accentual rhythm one finds in a Chaucerian decasyllable can be considered a secondary (ornamental?) function that is added to the basic structure of the line. In Pope, there is almost without exception an accent on syllable 4 and a break (caesura or coupe) following either accented syllable 4 or unaccented syllable 5. Syntax inevitably follows line structure, that is, a full stop follows each couplet. Pope’s heroic couplet, then, is an Anglicization in decasyllabic form of the classical French Alexandrine.

B.1.1.1. Chaucer:

The lyf so short, the craft so long to lerne,

Th’assay so hard, so sharp the conquering,

The dredful joye, that alwey slit so yerne,

Al this mene I by love, that my feling

Astonyeth with this wonderful worching

So sore y-wis, that whan I on him thinke,

Nat wot I wel wher that I wake or winke.

(Parlement of Fowles)

We could of course describe these lines as iambic pentameter, but to do so implies that Chaucer invented this meter, one for which Chaucer had no precedent. And Chaucer has an obvious precedent here: the stanzaic form, rime royale, is borrowed directly from the French; it is likely that the line structure, with the implied caesura following syllable 4, was borrowed as well. There is nothing here that cannot be analyzed in terms of the general rules for French decasyllable discussed above in chapter 3.

The couplets in the Canterbury Tales are just a further refinement, and there is less evidence of a caesura:

Whan that Aprille with his shoures sote

The droghte of Marche hath perced to the rote,

And bathed every veyne in swich licour,

Of which vertu engendred is the flour.

(General Prologue)

It might also be possible to see Troilus and Criseyde as a variant of Italian hendecasyllable, which we know Chaucer had before him as he wrote this poem.

To define Chaucer’s couplets as versions of a uniquely English form of iambic pentameter based on stress is to claim that Chaucer invented this unexampled verse form. More important, it requires us to believe that while doing this, Chaucer managed to ignore the nearly identical verse forms (French decasyllabic verse, Italian hen-decasyllables) that were immediately before his eyes as he wrote.

B.1.1.2. Pope:

’Tis hard to say, if greater Want of Skill

Appear in Writing, or in Judging ill,

But, of the two, less dang’rous is th’ Offence

To tire our Patience, than mis-lead our Sense.

(Essay on Criticism)

The easiest and simplest way to describe the form of Pope’s couplets is according to the rules of French decasyllabic verse (chap. 3): ten syllables, with a required accent on syllables 4 and 10 and caesura following syllable 4 or unaccented (post-tonic) syllable 5: x x x X ‖ x x x x x X, or x x x X x ‖ x x x x X.3 This syllabic description is not incompatible with standard descriptions of the dreaded iambic pentameter. But it seems to me much easier to begin with a system that allows variation (decasyllable with two required stresses), rather than propose a system (iambic pentameter) in which almost every line must be analyzed as an exception.

B.1.2. The rules for writing French verse were known and articulated by contemporaries of both Chaucer and Pope, and both poets read and studied French poems written according to these principles. Chaucer translated and wrote versions of poems by Deschamps and Machaut; Pope’s Essay on Criticism (1711) is a version of Boileau’s Art of Poetry (1673). One can certainly argue that the verse forms of Chaucer and Pope are specifically English and describe them further as a system of alternating WS, classical iambic pentameter, or a strange verse of four primary stresses. But why would one do this? The verse can be described just as easily by applying the principles of the very texts they translate: French texts in syllabic form. To ignore this entails arguing that the formal relation to the French sources is somehow (and very mysteriously) coincidental.

B.2. Purely Isosyllabic Verse

In This Age of Hard Trying, Nonchalance is Good and

“really it is not the

business of the gods to bake clay pots.” They did not

do it in this instance. A few

revolved upon the axes of their worth

as if excessive popularity might be a pot;

they did not venture the

profession of humility. The polished wedge

that might have split the firmament

was dumb. At last it threw itself away

and falling down, conferred on some poor fool, a privilege. . . .

(Marianne Moore)

To understand isosyllabic verse structure, one needs only to compare multiple stanzas: the metrical rules here define a stanza consisting of lines of six, twelve, eight, ten, and fourteen syllables. These lines are purely isosyllabic; that is, they are constructed solely according to the number of syllables, without regard to syllable quantity, accent, or syntax. Such lines are occasionally said to be based on French principles. But as noted in chapter 3, the only French verse that could be described as purely isosyllabic is experimental verse, such as that written by Verlaine in the late nineteenth century. All classical and romantic French verse has supplemental rules regarding accent, caesura, and even syntax, and line length is defined by the position of a terminal tonic accent, not by syllable count alone (that is, a ten-syllable line is defined as one with a terminal tonic accent on syllable 10, but one that may have more than ten syllables). The experimental isosyllabic verse of Moore and Robert Bridges (often mentioned in this context) has little to do with this.

C. Accentual Verse: Sprung Rhythm

The most notable example of modern accentual verse is what is often called “sprung rhythm” as found in Gerard Manley Hopkins. The term is invented by Hopkins himself in his 1918 Preface, where he describes his poems as written in various forms: some are written in “common English rhythm, called Running Rhythm,” others in “Sprung Rhythm,” and still others in mixtures of the two.

C.1. Hopkins’s Description

Although Hopkins shows some familiarity with theories of early Germanic verse, in his preface he describes his own version in classical terms. Lines consist of feet, and these feet consist of two elements, essentially what in classical meter are called the arsis and thesis, which Hopkins translates as “Stress” and “Slack.” “Every foot has one principal stress or accent, and this or the syllable it falls on may be called the Stress of the foot and the other part . . . the Slack.” There are thus two theoretical types of feet, “rising” and “falling,” that is, those with the stress on the second element, or those with stress on the first. In a striking note, Hopkins then shifts his ground from classical metrics to classical musical notation: “for purposes of scanning it is a great convenience to follow the example of music and take the stress always first, as the accent or the chief accent always comes first in a musical bar.” This effectively eliminates the notion of iambic or anapestic rhythm.

C.1.1. Hopkins describes sprung rhythm as follows:

Sprung rhythm, as used in this book, is measured by feet of from one to four syllables, regularly, and for particular effects any number of weak or slack syllables may be used. It [the foot] has one stress, which falls on the only syllable, if there is only one, or, if there are more, then scanning as above, on the first, and so gives rise to four sorts of feet, a monosyllable and the so-called accentual Trochee, Dactyl, and the First Paeon. And there will be four corresponding natural rhythms. (Preface)

These rhythms might be represented as X, X x, X x x, X x x x or ´,´ x, ´ x x, ´ x x x, where x indicates a syllable. In the above formulation, “rhythm” logically applies to individual feet, although it is not clear how such a thing as monosyllabic rhythm is possible. The rhythm of any particular line would necessarily consist of a combination of these four rhythms.

A poet can also bring in “licenses,” “as in the common ten-syllable or five-foot verse.” For sprung rhythm, Hopkins defines two licenses: rests as in music (although Hopkins claims he doesn’t use these), and “hangers or outrides,” that is, one, two, or three unstressed syllables (Hopkins’s “slack” syllables) added to a foot.

C.1.2. Hopkins indicates his rhythms typographically with diacritical marks and accents “where the reader might be in doubt which syllable should have the stress; slurs . . . little loops at the end of a line to shew that the rhyme goes on to the first letter of the next line.” Modern editions of Hopkins rarely include these marks.

C.2. Examples

In the context of the forms described here, we can see Hopkins as a proponent of accentual verse, through what I have called “allusions” to early Germanic alliterative verse. When describing accentual verse in his preface, however, Hopkins makes no mention of alliteration and what to modern readers is the most obvious feature of both his and early Germanic lines.

Look at the stars! look, look up at the skies!

O look at all the fire-folk sitting in the air!

the bright boroughs, the circle-citadels there?

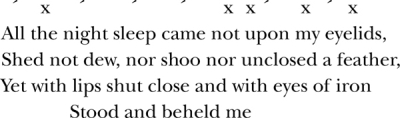

Down in dim woods the diamond delves! the elves eyes!

(Hopkins, “The Starlight Night”)

A line, as described by Hopkins, is composed of a predetermined number of feet, which is the same as the number of accents (although it is not quite in accord with Hopkins’s own language to speak of a line as containing a particular number of accents). But how one would determine these accents is not clear: even with Hopkins’s typographical aids, this is often anyone’s guess. Some lines can be reasonably analyzed as containing five stresses (or is it four?):

In this case, the metrical stress falls on alliterating or potentially alliterating elements, just as it would in earlier Germanic verse. But other lines have alliterating elements presumably on an unstressed syllable: is the scansion of the last line as follows?

Are we to ignore the implied stress on, say, “woods”? or the visual alliteration of the last two words? And in line 1, are we to pronounce the phrase “Look up” as part of a “falling foot” (thus leaving the syntactic emphasis on the word “up” unstressed?), leaving us with three stresses on the repeated word “look” and two more on “stars” and “skies”?

C.3. Precedents

Hopkins claimed his verse had classical and medieval precedent in Greek and Latin lyric verse and in “the old English verse seen in Pierce Ploughman” (a verse that Hopkins asserts ceased to be used since the Elizabethan Age). The classical precedent claimed by Hopkins is likely in the mixture of trochaic and dactylic feet, which, following contemporary descriptions of classical verse, Hopkins calls logaoedic verse, a form that combines “spoken” and “lyric” metrical elements. The term is no longer used in most classical manuals, and without it, the classical underpinnings of Hopkins’s verse may well disappear. It would be very difficult to describe his verse according to the language used in these manuals, and to do so would only obscure what Hopkins’s himself felt was the classical basis of his verse—the indifferent mixture of feet.

The early Germanic precedent for Hopkins is equally problematic, since the most prominent element, the alliteration, while clearly imitated by Hopkins, plays no part in his descriptions. The coincidence of stress and alliteration found in early Germanic verse and in verse of the so-called alliterative revival seems of secondary importance. Did Hopkins regard this feature of his verse, the most prominent feature for most modern readers, purely a matter of ornamentation? Or are we to see this verse, like other revived types, rooted in a creative misrepresentation of past forms?

C.4. Ezra Pound, “The Seafarer”

I close with an easier and far more amusing case. Pound’s translation of The Seafarer is a product of his early enthusiasm for languages. Although it is easy to share in this enthusiasm, it was also unfashionable among Anglo-Saxonists to admit such enthusiasm, as I discovered on more than one professional occasion:

May I for my own self song’s truth reckon,

Journey’s jargon, how I in harsh days

Hardship endured oft.

Bitter breast-cares have I abided,

Known on my keel many a care’s hol. . . .

This is a good example of allusion to form rather than imposition of form. Pound was surely exposed to Sievers’s half-line types in his Old English studies, but I doubt he could have passed a test on them, nor much cared about them.5 What he presents in this translation is (1) the alliteration he saw: “self song’s”; “journey’s jargon”; “Known on my keel, many a care’s hold”; and (2) what was convenient to represent: thus the perfectly literal “Bitter breast-cares ‖ have I abided.” As a whole, Pound’s Seafarer seems to represent not the Old English poem but rather the enthusiastic student’s effort to translate the Old English poem, perhaps in a parody of Hopkins’s own neo-gothic verse. This might explain the very elements so disparaged by serious Anglo-Saxon scholars, among whom Pound never pretended to be numbered: the wildly divergent formal elements; alliterating, strongly rhythmic lines combined with pedestrian prose; serious translations combined with the type of puns and jokes common among those learning a new language; parodic archaisms (“daring ado,” “Delight ’mid the doughty”). What is shown is not the real formal or even linguistic basis of the poem but the brilliant student’s inability or unwillingness to grasp it.

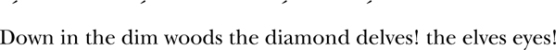

Lyrics to songs are analogous to what are known as “shape poems,” in that both are constructed on the basis of extraliterary forms. In a shape poem, the principle of organization is the physical shape of the printed or written words. When the text of such a poem is reproduced apart from that shape, there is little hope of recovering its exact organizing principle. A classical example in English is George Herbert’s “The Altar” (1633):

If this poem were printed apart from its shape, its underlying raison d’être might well be lost. Lyrics to songs are similar. If the song underlying a lyric is unknown, its versification will be unknown (and readers must be content with that).

The best we can do in such cases is to know that a musical basis (or implied musical basis) exists. And there are many clues that suggest that some such musical system is operable. Among these are:

a) title (e.g., “Song”)

b) line length; before the late nineteenth-century poems written in odd-numbered lines are often intended to be sung or have a musical form at their base.

c) seemingly random line combinations; most stanzas that are not formed in obvious patterns have a musical base or, like the English romantic ode, allude to one. John Donne’s familiar “Song” shows all these characteristics:6

Goe, and catche a falling starre,

Get with child a mandrake roote,

Tell me, where all past yeares are,

Or who cleft the Divels foot,

Teach me to heare Mermaides singing,

Or to keep off envies stinging,

And finde

What winde

Serves to advance an honest minde.

The printer distinguishes three types of line here, but we have no way of knowing whether what the printer thought was true; in subsequent stanzas, these are set differently, in a pattern that suggests line lengths as follows: 7, 7, 7, 7, 8, 8, 2, 2, 7.

The stanzas in a second Donne “Song” (“Sweetest love, I do not go”) are similar:

Sweetest love, I do not go

For wearinesse of thee,

Nor in hope the world can show

A fitter Love for me,

But since that I

Must die at last, ’tis best

To use myself in jest

Thus by fain’d deaths to dye . . .

Here, we have lines of four, six, and seven syllables, with relatively simple syntax. Although we do not know the music behind this stanza, we know that it is not purely experimental, nor is it built on iambic, trochaic, or more abstruse “logaoedic” forms; it is simply the lyrical embodiment of a preexistent song.

More elaborate and problematic versions include Donne’s “The Message”:

Send home my long strayd eyes to mee,

Which (Oh) too long have dwelt on thee,

Yet since there they have learn’d such ill,

Such forc’d fashions,

And false passions

That they be

Made by thee

Fit for no good fight, keep them still.

The three-syllable lines seem clearly related to those in the previous songs. But the possible musical basis is belied by the somewhat more difficult syntax: could such a poem be understood if sung? And from a stanza such as this, it is a short step to the following familiar stanza from Donne’s “Canonization”:

For Godsake hold your tongue, and let me love,

Or chide my palsie, or my gout,

My five gray haires, or ruin’d fortune flout

With wealth your state, your minde with Arts improve

Take you a course, get you a place,

Observe his honour, or his grace,

Or the Kings reall, or his stamped face

Contemplate, what you will, approve,

So you will let me love.

Here, the difficulty of the syntax, as well as the subject matter in later stanzas, speaks against a literal musical background; and it is interesting, looking through Donne poems comparable to this one in difficulty, that most show lines of even-numbered syllables. Again, the rule of the odd-syllable line indicating a musical background for French and English poems may apply. Somewhere in this progression of poems, Donne’s use of musical background becomes purely metaphorical, and he exploits the apparent freedom provided by musically based stanzaic forms. Such poems then are similar to the sonnet and the nearly contemporary English ode discussed in chapter 5, B.

| For the modern reader, verses with a musical basis are simple to detect: they are in short repeating stanzas; if there are three or more stanzas, it is a simple matter to determine scribal or printing errors or even curiosities of pronunciation. Each line in each stanza will have the same number of syllables, and each stanza will incorporate the same rhyme scheme. Nothing is to be gained by a more elaborate formal analysis involving inverted feet, substitutions, etc. And we would be better off, perhaps, writing a pseudo-Elizabethan song to accompany them than to burden them with the classical and too-often standard language of versification.

Texts: English texts from the facsimile images of early editions in Early English Books Online, eebo.chadwyck.com, and from Literature Online, lionchadwyck.com; texts of Gerard Manley Hopkins are from Poems (1918), www.bartleby.com/122/100.

References: John Dryden, preface to Fables, Ancient and Modern (London, 1700); G. Gregory Smith, ed. Elizabethan Critical Essays, 2 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1904).

1. One of the explicit principles for the determination of a quantitatively long syllable was the accent itself. “Above all the accent of our words is diligently to be observ’d, for chiefely by the accent in any language the true value of the syllables is to be measured” (Campion). By “true value,” Campion means the quantity of the syllable, long or short. The coincidence of accent and quantity in such cases meant that clashes of the two systems were relatively infrequent. See Thomas Campion, Observations in the Art of English Poesie (1602) in Smith, 2:351.

2. Campion’s Latin examples are unfortunately mis-scanned; see Smith, 2:334.

3. This is similar to but not strictly a lyric caesura, which in French medieval verse follows unaccented syllable 4.

4. To describe this line in Hopkins’s own terms likely requires invoking the term anacrusis to describe the unstressed opening syllable “The”; the first foot would then be the monosyllabic “Bright,” the second foot the dactylic “boroughs the,” etc.

5. For example, the forbidden X x x X half-line type frequent here.

6. I quote the 1633 edition, not because it is authoritative, which it is not, but because the spelling is sometimes more apt to indicate actual line structure than that of modern editions.