Who ever would think a Fairy Godfather could be a nuisance?

—BARNABY, in Crockett Johnson, Barnaby, 28 Apri l1942

Freed from the daily obligation of writing and drawing Barnaby strips, Crockett Johnson at last had some time for all his other Barnaby-related projects. The second issue of the Barnaby Quarterly appeared in November 1945, with the third issue following three months later. Johnson was working on a third Barnaby book, not a collection of redrawn daily strips but “an illustrated story.” Having already illustrated two children’s books and drawn a comic strip that appealed to young people, Johnson was considering writing for children. The new book never appeared, likely because the Barnaby play needed extensive revisions. The idea of making it a musical fell by the wayside, and Jerome Chodorov, cowriter of the successful stage adaptation of My Sister Eileen, began working on it.1

Though Johnson remained active on the left, the Popular Front coalition unraveled, and its members began to attract suspicion. In March 1946, former British prime minister Winston Churchill gave what would become known as his Iron Curtain speech, warning the United States that the Soviets sought the “indefinite expansion of their power and doctrines.” American conservatives took note. A month later, when the Philadelphia Record wanted to claim that the Independent Citizens Committee of the Arts, Sciences, and Professions had communist influence, the paper pointed to Johnson: “Suppose we look at the directors of the ICASP. Among them are the following, all closely tied with the Communist Party and/or Daily Worker: Howard Fast, Henrietta Buckmaster, Jose Ferrer, Crockett Johnson, Lillian Hellman (whose trip to Russia was paid for by the U.S.S.R.), and Paul Robeson.” Further arousing the Record’s suspicion was the fact that Johnson supported New York’s 1946 May Day parade, as did William Gropper, Rockwell Kent, Edward Chodorov (Jerome’s brother), Fast, Clifford Odets, and Jerome Robbins.2

Though Johnson was not secretly working for Soviet Russia, the Record’s claims had some merit. Like many in the communist and peace movements, Johnson hoped that the wartime alliance between the United States and the Soviet Union could be extended into the postwar period, marking a new era of peaceful cooperation. On 14 May, he donated one hundred dollars and attended a New Haven “Peace and Security Rally” sponsored by the Communist Party of Connecticut. He joined the National Committee to Win the Peace, which sponsored the Win the Peace Conference at New York’s Manhattan Center near the end of June 1946. As the group’s ad in the Daily Worker noted, its members hoped “to carry forward F.D.R.’s policies of peace based on Big Three unity.” Insinuating that Win the Peace was a communist-front group, Time magazine reported that at the conference, “in a strong Russian accent, delegates clamored for destruction of all atom bombs, [and] acceptance of the Soviet plan for ‘outlawing’ atomic war.”3

Reflecting Johnson’s activism, Barnaby both grew more politically engaged and conveyed wariness about political engagement. Although Johnson was no longer drawing and writing the daily strips, he remained involved in their planning. He was influential in developing a plot line that began in July 1946 about O’Malley persuading the mayor and town council to solve the postwar housing crisis with tent cities. That month and the next, Barnaby’s father, Mr. Baxter, initiated petitions and organized protests, rallying citizens against the tent cities and in favor of proper housing. By the end of the month, Baxter’s efforts had persuaded the council to build low-cost housing, though he received no credit for the idea. Baxter says he is satisfied with the results, but the many meetings tire him: “I’m through with politics. You make friends. But you also make enemies. Life’s too short.”4

While Johnson was attending lots of meetings, Jerome Chodorov’s draft of Barnaby and Mr. O’Malley had become a hot Hollywood property. For the film rights, Columbia Pictures bid one hundred thousand dollars plus 5 percent of the film’s profits if the play ran for five weeks, with an additional 1 percent for each week up to 30 percent. The authors would receive 60 percent of that money—half to Johnson and half to Chodorov. RKO then outbid Columbia, with a down payment of one hundred thousand dollars and a final amount that might rise as high twice that, depending on the play’s success. Having created Barnaby in hopes of gaining a steady income, Johnson was now poised to become quite wealthy.5

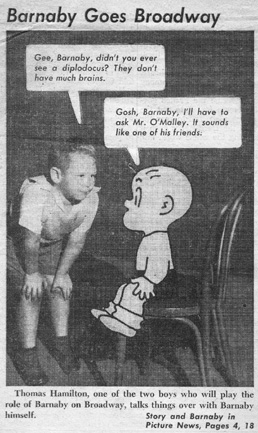

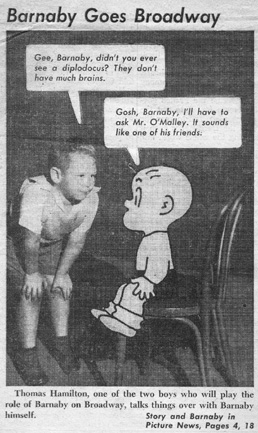

Producers Barney Josephson and James D. Proctor likewise thought they would do very well with their first venture. To direct, they secured Charles Friedman, director of the hit Broadway musicals Pins and Needles (1937–40) and Carmen Jones (1943–45). Offering to help Friedman stage Barnaby and Mr. O’Malley was playwright Moss Hart, author of You Can’t Take It With You (1936–38) and The Man Who Came to Dinner (1939–41), both of which became successful films. Director Elia Kazan read Chodorov’s draft and thought the play would be great. Chodorov had focused the story on two main narratives. First, the Baxters’ concern about their son’s “imaginary” fairy godfather prompts them to consult a child psychiatrist. The doctor advises the boy’s father to make himself “more glamorous in the child’s eyes,” so he runs for the New York State Assembly. In a variation on O’Malley’s campaign for Congress in Johnson’s strip, Baxter competes against the well-funded Homer Mintleaf, whom O’Malley criticizes for wasting “thousands of dollars on cheap exhibitionism like that sky writing campaign…. The voters are being asked to support a businessman—well, if this wholesale waste of money is Mintleaf’s idea of business give me a starry-eyed idealist every time!” Barnaby repeats these remarks to reporters, drumming up support for John Baxter. The play ends with O’Malley flying off to Albany to assist Baxter in his new political career. Much of Johnson’s dialogue appears intact, but Chodorov also invents material to stitch together the narrative strands. In mid-August 1946, rehearsals for Barnaby and Mr. O’Malley began, with Irish-born Broadway veteran J. M. Kerrigan in the role of O’Malley. More than six hundred boys tried out to play Barnaby, with the part going to seven-year-old Tommy Hamilton, whom Johnson said looked “more like Barnaby than any real child I ever expected to meet.” To prepare for its arrival on Broadway in early October, Barnaby and Mr. O’Malley would open in Wilmington, Delaware, on 6 September, moving to Baltimore on 9 September and to Boston a week later.6

As Barnaby headed for the stage and possibly the screen, Ruth Krauss worked on a children’s book that would use anthropology to debunk stereotypes, echoing the approach of The Races of Mankind, which United Productions of America had adapted into a successful cartoon, The Brotherhood of Man, the preceding year. Ruth’s first chapter, “On Women,” noted that for Africa’s Dahomey people, “Women form one third of standing army”; among the Bathonga, “Women are the great story-tellers.” The second chapter, “On Men,” reported that in Manus society, “men tend the babies,” while the Tchambuli see men as having “the flighty character.” Her fourth chapter was explicitly anti-ageist. Chapters 3 and 5 countered dominant assumptions about humanity. Hoping to prove that killing was not a “natural” part of human behavior, she pointed out that among the Todas, “there no record of any murder” and that certain Australian peoples had never had war. Having just seen the second world war in three decades, Krauss was drawn to the idea that a better future began with the next generation. With proper education, these children might grow into adults less inclined to pursue war as a means of resolving differences.7

Tommy Hamilton meets the character he portrays on stage. PM, 1946. Image courtesy of Thomas Hamilton.

The fall of 1946 saw the publication of The Great Duffy to generally good reviews. The San Francisco Chronicle’s Florence Little thought that the book would entertain children, citing one young reader who judged it as good as Dr. Seuss’s And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street (1937). Marjorie Fischer’s New York Times review called the book “the child’s equivalent of ‘The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.’” Kirkus agreed that the book’s “adventures … catch the ‘Walter Mitty touch.’” Praising the book’s “imaginative understanding of real small boy psychology,” the review considered The Great Duffy a “delectable book for the distracted parent who wants to wean small sons from too constant demand for comics.” However, the book was “‘banned’ by the Child Study Association, who even refused to take ads from Harper.”8

The production of Barnaby and Mr. O’Malley continued to be plagued by problems, many of them related to its costly special effects, which included making O’Malley fly out over the audience. The play was late opening in Wilmington and was staged only twice there before moving on to Baltimore; the planned weeklong run there ended when the production closed for repairs after just two shows. Josephson and Proctor remained convinced that Barnaby and Mr. O’Malley was “a potential hit” but conceded that it “needs revision.” A lot of money had already been invested in the show—forty-four backers had contributed more than eighty thousand dollars. The producers dismissed the director and spent twelve weeks to reworking the play, hoping to open in New York before Christmas. Johnson had been only minimally involved in adapting Barnaby for the stage, and though he was not happy about being left out, had held his tongue, wanting to give the producers some “aesthetic autonomy.” Now that the show had flopped, however, he offered his assistance. Josephson accepted, assuring Johnson that he would work closely with Chodorov on the revised version.9

With Barnaby and Mr. O’Malley in limbo, Dave and Ruth took a vacation, driving to New Orleans and then flying to Mexico. They spent a few days in a “little jungle” in the Yucatán, enjoying the warm weather, fresh fruit, and spicy food. Back home, Johnson continued his political activities. At the end of December 1946, he had been a delegate to the joint convention of the Independent Citizens Committee of the Arts, Sciences, and Professions and the National Citizens Political Action Committee. The two groups voted to merge, creating the Progressive Citizens of America (PCA). In June 1947, he and Mischa Richter organized a PCA-sponsored reception for secretary of commerce and former vice president Henry Wallace in Westport, Connecticut.10

While her husband was preparing for Wallace’s visit, Krauss was working on another book, “Mr. Littleguy and the Laundry.” Ursula Nordstrom at Harper had turned down a draft, and Krauss again sought help from the Bank Street Writers Laboratory. The group generally liked the tale, which involved a laundryman who prefers to “paint little pictures on clothes instead of just conventional laundry marks.” Some customers complain, but others like the pictures, and his shirts eventually cause a sensation in the art world. Though the members of the Bank Street group “thought the writing was not too rough,” Krauss disagreed: “I know they’re wrong.” Krauss pushed her doubts aside and sent the new version to Simon and Schuster, which replied that the story would not suit the Little Golden Books series. The editors encouraged her to send in a revised version, and Krauss worked on it some more and again sent it to Nordstrom. Yet another rejection followed: Nordstrom declared the story too “noisy” and suggested that Krauss write another story featuring the central character. A discouraged Krauss abandoned Mr. Littleguy and resurrected “The Last of the Mad Waffles,” a chapter of a novel about the Depression that she thought might be adaptable into a story for children.11

Johnson turned his attention to Barnaby and Mr. O’Malley, working in Rowayton on plot, staging, and production ideas and lining up a Manhattan apartment so that he could come down to New York and work on the play with Chodorov. However, Chodorov had arranged with Josephson and Proctor to turn the project over to Kay Van Riper, screenwriter for Busby Berkeley’s Babes in Arms (1939) and a half dozen Andy Hardy movies. Johnson did not learn of the change until he received a note requesting his signature on some legal documents during the first half of 1947. He sent an irate telegram to the producers and hopped on a train to New York. He obtained a copy of the script just an hour before meeting with the producers and Van Riper. Van Riper stuck with the project for only a few months before dropping it, and the producers gave up. Again, however, they neglected to tell Johnson. Although Johnson’s involvement with the play had been minimal, some investors blamed him for its failure. He asked Josephson to correct this impression and in a rare display of anger told him that the producers and Jerome Chodorov had managed “the most offensive personal and professional insult ever callously and deliberately inflicted on a writer” and the most “fantastically irresponsible treatment ever accorded a literary creation.”12

As Barnaby and Mr. O’Malley slowly imploded, Johnson began to think about other projects. He dropped in to see William Sloane, former vice president of Henry Holt and Company, publisher of the first two Barnaby books, who in 1946 had founded a new publishing house, William Sloane Associates. While waiting to see Sloane, Johnson began to read one of the company’s latest novels, Ward Moore’s Greener Than You Think (1947), a gonzo satire of public apathy, bureaucratic incompetence, government hypocrisy, and media appetite for disaster. Johnson told Sloane, “Say, this is the kind of book I like,” and that fall, those words appeared at the top of a full-page advertisement in the New York Times Book Review. Johnson’s name still carried a certain cultural cache. As Coulton Waugh wrote in The Comics, published the same year, Barnaby’s “very discriminating audience” would likely “influence the course of American humor for years to come.” “Underlying [Barnaby’s] fantasy” was a “sharp, razor-edge of social satire,” and the strip provided “a patch of cheerful, sunny green in the scorched-dust color of our times.”13

Dave and Ruth were now living comfortably in Rowayton. By the summer of 1947, they had purchased the first TV in town, and Fred Schwed, George Annand, and other friends frequently dropped in to watch tennis, boxing, baseball, and football. With martinis and snacks at their fingertips, the blinds pulled down to keep out the sun, and the TV showing their favorite games, it was, according to Schwed, “a good way to spend the summer in the big outdoors.”14

That summer, the daily Barnaby strip created by Jack Morley and Ted Ferro began to drift from its original premise. The topical satire became less sharp, and O’Malley’s diction lost some of its lexicographical exuberance. Following a misunderstanding during which Mr. Baxter threatens to shoot Mr. O’Malley, Barnaby’s fairy godfather leaves the narrative from 24 May through 1 July, by far his longest absence from the series. Much of Barnaby’s particular style had come from Johnson, and Ferro was simply not Johnson. Johnson returned to writing the strip in September 1947, though Morley stayed on to do the art, and the two men worked jointly on the strip until 1952. Johnson wrote the dialogue, planned the layout, and often provided Morley with rough sketches to use as guides. For the remainder of Barnaby’s run, Johnson remained actively involved in the strip’s creation.15

Harper released Krauss’s The Growing Story, illustrated by Phyllis Rowand, in 1947 to complimentary reviews predicting that child readers would identify with the protagonist. Writing for the New York Herald Tribune, May Lamberton Becker said, “If the five-year-old for whom you are choosing a story is like others of his age he finds the rate of his own growth a matter of warm interest.” The New York Times’s Lillian Gerard wrote, “The phenomenon of growth, combined with a child’s interest in himself, makes this a fascinating story, easy to read aloud and discuss.” Kirkus noted that the “author of some of our very favorite juveniles … has again given us a satisfying, lovely text that will get repeated reading from four to six year olds” and described Rowand’s drawings as “modern and stylized without sacrifice of a certain tenderness.”16

Frequently asked why she never had children, Ruth often answered that she knew that she was not responsible enough to be a parent. This may be true: Ruth found it easy to talk to children because she was so like a child; her emotional receptiveness to young people’s experiences made her a good friend to children but might not have made her a successful mother. In any case, Ruth and Dave did not need to have a child of their own. They had Nina Rowand Wallace, who was like a daughter to them. And they had the children of their imaginations. Dave had Barnaby. Ruth had Duffy and the unnamed protagonists of The Carrot Seed and The Growing Story. Many of the greatest creators of children’s literature—Beatrix Potter, Lewis Carroll, Edward Lear, Margaret Wise Brown, Dr. Seuss, Maurice Sendak, and James Marshall—had no biological children. In a practical sense, time not spent on raising children could instead be devoted to writing for children; however, childlessness meant that these authors had to find inspiration elsewhere. Crockett Johnson drew on his memories of his childhood. Ruth Krauss looked to folklore, to imagined conversations with neighbors, and to unpublished work for adults. Though all three methods brought her success, she had not yet found a reliable muse. She had not yet realized that her best source of ideas might be children themselves.