Hosting the Olympic Games had been a twinkle in Willi Daume’s eye since the early 1960s. The German sports functionary had become a devoted member of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in 1956, and two events just four years apart must have given him a taste of what it would be like to stage the movement’s premier event. In 1959, Munich, the home city of Avery Brundage’s longtime friend and fellow committee member Karl Ritter von Halt, hosted the IOC session. When Nairobi refused to admit the South African delegation in 1963, the Federal Republic stepped into the breech, offering the spa town of Baden-Baden as an alternative.1 The latter proved a sumptuous occasion with “six princes, one marquis, two counts, three barons, five generals, two sheiks [and] a sprinkling of millionaires” settling into a “casino . . . overlooked by turreted castles.”2

The erection of the Berlin Wall gave political grist to Daume’s private ambition. In the winter of 1962 to 1963, he and the then mayor of Berlin, Willy Brandt, plotted to bring the 1968 Olympics to both parts of the divided city.3 Without troubling to contact the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and ignoring the disapproval of three Western allies4 and a Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and Free Democratic Party (FDP) cabinet in Bonn reluctant to hand political capital to a rising Social Democratic Party (SPD) star,5 Brandt submitted a confidential bid to the IOC.6 Daume worked the committee’s networks, conducting private discussions with the influential Russian member Konstantin Andrianow, who, in the spirit of Khrushchev’s new politics of coexistence, assured him of Soviet support.7 But when news of the secret bid leaked, the Western allies brought the matter to a swift conclusion with an unambiguous call to the West German Ministry of the Interior.

By the time it came to bidding for the next Games in the schedule, disputes between East and West Germany at the IOC had become so heated that the committee would have treated a Berlin proposal as a deliberate act of provocation (see chapter 6). By the same token, the West Germans, and Daume in particular, enjoyed some measure of sympathy among committee members, and after Asia (Tokyo 1964) and the forthcoming foray into Latin America (Mexico 1968) there was a widespread view that the Games should return to Europe in 1972. The decision was due to be made in Rome in April 1966, and after consulting Brandt (who in the meantime had lost the 1965 general election but established himself as the undisputed leader of the SPD) from the IOC session in Madrid in October 1965, Daume had to move quickly to find a German city willing to undertake the task.8

It is not clear whether Brandt recommended Munich. At any rate, the Bavarian capital would have suggested itself for several reasons. First, Munich had made a very favorable impression on IOC members in 1959.9 Second, and more importantly, in Brandt’s party colleague Hans-Jochen Vogel, the city possessed an energetic young mayor who could be relied upon to rise to the challenge. Vogel’s rivals in other potential cities belonged to the prewar generation and, despite their moral standing, risked reminding international voters of the recent past. Arnulf Klett had governed Stuttgart continuously since 1945, and Herbert Weichmann, a former Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany, led Hamburg’s senate. Frankfurt, under Willi Bundert, a former member of the Kreisau circle and the war-time resistance who had spent eight years in a GDR prison on charges of espionage, would have engulfed any Olympic enterprise in East-West controversy. Vogel’s fresh face and dynamism stood out by comparison and offered the possibility, at least, of assuaging residual suspicion abroad of Munich as the former “capital of the Nazi movement” (Hauptstadt der Bewegung).

Third, the fact that Munich was not a capital but only a medium-sized city would offer an antidote to what Olympic insiders had begun to see as the age of “gigantism.” From 1960 to 1968, in Rome, Tokyo, and Mexico City, the Games had sprawled over increasing distances (in Mexico up to 589 kilometers) and aroused fears about the event’s practical and ethical sustainability. As a city renowned for high culture, Munich would allow an ideological rescoping of the Olympics, selling itself as a return to the founder’s belief in the harmony of sport and the arts.10 Finally, unlike comparable cities in the Federal Republic, Munich had not yet built a major stadium such as Frankfurt’s Waldstadion or Hamburg’s Volksparkstadion. Conveniently, however, the city possessed a brown-field site of around 280 hectares (about a square mile) just four kilometers from its historic center. Already approved by the city council for future use as a stadium, it simply awaited funding. Munich, therefore, would not only be in a position to mount a swift bid, but its lack of sporting venues would count in its favor: faced with a tabula rasa, the international sports federations, whose opinions weighed heavily when the IOC made its final decision, would have the opportunity to demand and influence the creation of state-of-the-art modern facilities for their respective disciplines.11

While IOC statues stipulate that Games are awarded to cities, these require the backing of national governments. The only Olympics since 1945 to circumnavigate this condition took place in Los Angeles 1984, when a troubled IOC had only one candidate from which to choose. In West Germany, the federal structure of government potentially complicated matters in that the Land of Bavaria would be required to give its consent as well. In the event, however, the three political agencies agreed almost immediately. Daume put his proposal to Vogel on 28 October 1965; Chancellor Erhard, the cabinet, and the budget committee (Haushaltsausschuß) of the Bundestag consented on 29 November, 2 December, and 8 December respectively; the Bavarian government assented on 14 December, the West German National Olympic Committee on 18 December, and Munich City Council on 20 December. When the application was submitted to the IOC in Lausanne before its deadline at the end of the year, the first stage of Munich’s bid had taken barely three months. The astonishing rapidity with which each party pledged its support is clear indication of what was at stake.

When Daume visited Munich City Hall in October 1965, Vogel was flabbergasted. Folklore has it that he met his visitor’s inquiry with an exclamation of “Sauber!”—a Bavarian term scarcely translatable into High German let alone English, but which revealed his mood to be one of “productive desperation.”12 After consulting widely—with the city’s Council of Elders (Ältestenrat), some fifty-four local institutions, associations, and pressure groups,13 close associates (probably Hubert Abrefß, then head of the city development department, and Klaus Bieringer, head of Munich’s cultural affairs department), and national party-leader Brandt14—Vogel’s shock subsided and his initial concern about costs soon developed into excited cooperation.15 Even in the precommercial days of the 1960s, the Olympics’ effect on civic boosterism was fairly evident. One year earlier, the city’s deputy mayor, Georg Brauchle (CSU), had wistfully remarked at the 1964 Winter Olympics in Innsbruck that Munich would get its long-cherished “Großstadion” (major stadium) much sooner if it were to host the Games.16 Munich, moreover, was in the midst of radical planning. In March 1960, an SPD initiative had led the council to commission a strategy that aimed to produce “desirable order for the city’s urban and traffic development for the [subsequent] thirty years.”17 In keeping with the technocratic spirit of the age, the ambitious young mayor had won his first election the same month on a pledge of “farsighted and efficient city planning” and duly established one of the first specially dedicated groups of its kind on taking up office.18

In 1960s West Germany, however, financial means lagged somewhat behind wishful technocratic optimism. As the population growth of the “economic miracle” years began to outstrip fiscal capacities, communes experienced increasing difficulty. While private consumption and investment continued to rise dramatically, public expenditure on housing and municipal infrastructure remained largely stagnant. Set against dramatic increases in motorization and demands for greater living space, cities struggled to provide an acceptable quality of life. While the communes (excluding the city-states of Hamburg and Bremen) had invested around DM 500 billion in construction between 1948 and 1962, they had done so largely on credit. By 1968, debtor communes owed a total of DM 35 billion, and Munich, whose individual debt had increased ninefold from DM 172 million at the end of 1955 to over DM 1.5 billion in early 1965, topped the table.19 In 1965, the city’s budget had to cover two-thirds of expenditure on roads, housing, schools, and hospitals on credit despite strong advice from the regional government of Upper Bavaria to reduce borrowing.20 By the eve of the Games, the mayor would be openly lamenting a system that required a city to host the world’s largest sports event in order to fund basic public facilities.21

The parlous state of Munich’s finances resulted from a period of accelerated growth after 1945 which led to housing shortages, rising land and property prices and pressure on basic infrastructure and amenities. Having served largely as a regional administrative center, underindustrialized Munich attracted more returnees and evacuees after the war than any other West German city. Its immediate postwar population of 480,000 increased by an average of 24,200 each year from 1950 to 1971, with the growth rate reaching a net gain of almost 110,000 between 1969 and 1971 alone. As early as 1950, it had matched its prewar population of 830,000, crossed the one-million-barrier in 1957, and hit 1.2 million on the eve of the bid in 1965.22 During the Olympic year itself, the population peaked at 1.34 million.23 In twenty years, therefore, both in absolute (462,795) and relative terms (55.7 percent), Munich had grown more than any other West German commune. At the same time, the negative fallout associated with rapid expansion also brought significant economic advantages, as Munich benefited from the relocation of many vital industries. While cities in the Ruhr such as Essen and Dortmund shed more than 40 percent of their industrial employment in the 1960s, and Hamburg, the second-largest city in the Federal Republic, experienced an 11-percent decline, Munich increased its share in the secondary sector by 11 percent.24 The city profited from the Cold War in general, and the marginalization of (West) Berlin and division of Germany in particular. Taking in seventy thousand expellees from the Sudeten region of Czechoslovakia, the area became home to its export-oriented industries.25 The influx of highly qualified refugees from the GDR, too, meant that the printing trade of Thuringia and the textile manufacturing and machine-building of Saxony took hold in Southern Bavaria, while important publishing houses relocated from Leipzig, and the film industry abandoned the UFA grounds in East German Babelsberg. Electrical and, later, communication technology giant Siemens moved its headquarters from Berlin to Munich in 1949, creating fifty thousand work places.26

There was a certain inner logic to the largest center in the south replacing the former capital in the north as the country’s “Olympic city.” Between 1950 and 1970, the population of West Berlin had stagnated, with minor fluctuations, around 2.2 million, its age profile tilting firmly toward the elderly.27 Munich, by comparison, boasted the youngest population in the Federal Republic, a fifth of its residents having been born after 1945 and two-fifths predicted to be under thirty by 1972. When Vogel emphasized this fact in his speech to the IOC in Rome,28 he was doubtless hoping to banish thoughts of the 1938 Munich Agreement and its aftermath.29 But the vital truth behind the mayor’s statistics was that in the mid-1960s, Munich desperately needed to rebalance the positive and negative consequences of its postwar boom. Influenced by prominent critiques of postwar America—John Kenneth Galbraith’s The Affluent Society (1958) and Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961, German translation 1963)—Vogel had been concerned for some time about the fabric of modern society. In it he saw a world increasingly defined by a disparity between private wealth and public poverty, spending on trivial consumer needs over vital communal services, and an unnatural functionalist division between work and living spaces.30

For the city administration, this meant solving crucial problems of housing and transport and, as Vogel regularly put it, “adapting communal institutions to the growing and ever-changing demands of [the municipality’s] citizens.”31 In 1963, his chief city-planner, Herbert Jensen, had been given council approval for ambitious plans to “resist [any further] shapeless accidental development and the very alarming dissolution of the city.”32 In late 1965, therefore, it must have been clear that hosting the Olympics would accelerate the city’s cause by many years, and do so largely on someone else’s tab. Indeed, some of Jensen’s grander projects, such as the development of the S-Bahn and U-Bahn, would be completed within five and seven years rather than the fifteen originally anticipated.33 With Land and federal support, the city paid only DM 31 million of the total DM 490 million for the former, with Bonn covering the lion’s share of the latter.34 It is hardly surprising, then, that even before the bid was properly formulated, other communes believed Munich had struck gold, and a conglomerate in the Rhine-Ruhr region mounted a short-lived counter-bid of its own.35

Despite the strong majorities that secured the SPD’s power in Munich after 1945, Bavaria was a conservative stronghold. Minister-president Alfons Goppel remained virtually unchallenged between 1962 and 1978 and was surrounded by a strong cast of Christian Social Union (CSU) politicians, most notably party chairman Franz Josef Strauß. As a result of the latter’s stints in two Adenauer governments (as minister for special tasks, nuclear energy, and defense), Munich and its surrounding region had cornered a large share of the German aircraft, atomic, and armament industries (e.g., Messerschmitt-Bölkow-Blohm and Krauss-Maffei). Superficially, one might have expected a certain tension between the region’s left-wing core and its right-wing milieu, but an underlying similarity of outlook compensated for the sometimes heated differences. Vogel, after all, might have become a CSU member, and within the SPD he had attached himself to the informal but powerful right-wing, conservative grouping known as the Seeheim circle and stood firmly behind the modernization decided at Bad Godesberg. Pragmatic rather than ideologically obsessed, Vogel shared the same convictions as the CSU leadership when it came to Munich and Bavaria: the imperative of economic growth. His relationship with Goppel and Strauß was cordial enough for them to channel resources to Upper Bavaria, and Munich in particular, as one of the Land’s main areas of expansion.36

Although the bid initially met with opposition from high-ranking civil servants in the finance and culture ministries of the Bavarian government, senior party figures gave it their full support. Strauß, a south German cycling champion in his youth, was a keen sportsman and Goppel—along with the two ministers most closely involved, Ludwig Huber (minister for culture and later an influential member of the Organizing Committee) and Konrad Pöhner (finance minister who later played a key role in the Olympia-Baugesellschaft [OBG], the public corporation entrusted with the construction of the Olympic venues)—understood the potential benefits for the region. While there could be little doubt about the financial strain, many came to agree with the Bavarian minister-president, whom the Spiegel quoted as sighing patriotically: “One has to grasp the nettle.”37 The CSU grandees presumably calculated they had little to lose. If Munich won, the overall gains for the Land would outweigh their own financial outlay and any kudos given to the “red” mayor of Munich. If it failed, the defeat would be Vogel’s alone. When Strauß portrayed the Games in the Bundestag (on 30 November 1965) as a golden opportunity to correct Germany’s “distorted self-representation” abroad, his remarks were doubtless sincere but masked considerable Bavarian self-interest.38

Just as Munich bargained on the Games enhancing financial support for the city, the Land could count on a flow of investment to its designated growth area at only minor additional cost to taxpayers. While Munich would profit most, significant sums would spill over into surrounding CSU strongholds and help counteract the drift of young people, in particular, from the countryside to the cities.39 In this sense, Munich and Upper Bavaria shared common interests and incentives. Unfortunately, no comprehensive economic analysis was conducted at the time, but as a few examples indicate, exposure to international audiences offered Bavarian businesses unprecedented public relations opportunities.

Occasionally, local companies were outbid by international rivals. Coca-Cola, for instance, which had enjoyed a strong association with the Olympics since Amsterdam 1928, out-priced Pepsi and two local firms for exclusive soft-drinks rights on the Olympic sites by guaranteeing the OC at least DM 2 million from its profits.40 Sometimes national competitors with key personal contacts, such as Daimler-Benz, would work themselves into pole position too.41 The Stuttgart company had its Mercedes logo and slogan—“Fair in sports. Fair on the road”—printed on the back of every Olympic ticket for an undisclosed sum, in addition to loaning 1,700 cars, buses, and trucks for the Games, offering 275 middle-of-the-range MB 200s at significantly reduced prizes for the Olympic lottery, and providing drivers, luxury MB 600s, and price reductions for the IOC and other VIPs.42 Without Vogel’s intervention, the Munich-based automobile and motorcycle manufacturer BMW would not have even broken into the Olympic car pool.43

On the whole, however, local firms, if competitive, were given the rub of the green. Siemens, rather than its American competitor IBM, won the contract to supply the data-processing system Golym (in Mexico 1968, the Italian firm Olivetti had been prone to embarrassing glitches).44 Although the DM 22.5 million charged to the OC barely covered a third of the cost, the company’s investment was easily recouped in exceptional profits, long-term research and development advances, and publicity gains.45 Golym held much fascination for those reporting on the high-tech nature of the Games, was discussed extensively in the foreign press, and lingered upon lovingly in the official film. Junghans, a Black Forest firm owned by a Nuremberg holding company, almost lost the timing-keeping contract to a free offer from its Swiss competitor Longines, but various interventions led to both firms sharing the responsibility.46 Local sports-shoe rivals Adidas and Puma were granted contracts to sell and—against strict IOC regulations—give their products away for free in the Olympic village, thus ensuring that athletes’ feet (the only part of the body on which a logo could appear) would be clad for all the world to see in Bavarian brands. Adidas built a hotel to host prospective medal-winners, branched into sportswear, and calculated that 80 percent of competitors chose to wear its shoes at the Games.47 Despite a better offer from foreign manufacturers of tartan tracks, the distinctive Adidas stripes ran and jumped across native Rekortan, Hans-Dietrich Genscher having persuaded the OC that “giving this contract to a foreign company would completely undermine the German manufacturer in the eyes of the world and give the international competitor a worldwide monopoly.”48

The Land would also benefit from the logistical impossibility of hosting every event in Munich itself. Despite disagreements within the IOC, several competitions took place outside the city limits, in some cases even in newly built facilities.49 The opening rounds of the soccer tournament took place in Passau, Regensburg, Ingolstadt, Augsburg, and Nuremberg, with some team handball games being played across the state border in neighboring Baden-Württemberg (Böblingen, Göppingen, Ulm).50 A riding stadium was built east of the city in Riem; and, under pressure from the international rowing and canoeing federations, a luxurious water-sports site was constructed north of the city in Feldmoching at the cost of US$23 million (approximately 5 percent of the final Olympic budget).51 In Augsburg, some eighty kilometers to the north, an “Ice Channel” was commissioned for the Olympic canoe slalom competitions, much to the ire of Avery Brundage who grumbled that this new event had been included in the program for 1972 on the condition that it took place in Munich itself.52 In light of the infrastructural, economic, and sporting boost that would inevitably accrue to the region, it is hardly surprising, therefore, that the Bavarian parliament’s decision to back the bid and bear one-third of the cost was unanimous.53

Of the three parties responsible for winning and carrying out the Games, the federal government proved the most difficult to convince. There are different accounts of what happened when Daume, Vogel, Brauchle, and Goppel visited the chancellor’s bungalow on 29 November 1965.54 Least credible is Daume’s claim that Ludwig Erhard was “immediately all for it,” even uttering the phrase synonymous with West Germany’s remarkable postwar rise: “Wir sind wieder wer [We are back]. We are able to do this and we are not that poor.”55 Vogel’s version, in which the chancellor appeared at first to waver, seems more realistic.56 Clearly warned by Ludger Westrick, the head of the Chancellor’s Office, Erhard doubted Vogel’s budget of DM 497 million. A handwritten note from the meeting shows the Munich mayor spinning the deal, pointing out that the Bund, which normally contributed 40 percent of the cost of urban road building schemes, had already agreed the funds for traffic infrastructure.57

Two hours later, however, Erhard consented, supposedly remarking that “one shouldn’t always mope around and give the country unpleasant news.”58 That same day, in fact, he had been forced to announce public-spending cuts in the Bundestag because of slow economic growth in the second half of 1965.59 But in all likelihood, the chancellor’s agreement came from more than a whim or the transient desire to sweeten a bitter pill. As with Vogel a month earlier, the moment of personal opportunity would not have escaped him. Having stepped in as chancellor after Adenauer’s resignation in 1963, Erhard had been granted a popular mandate for the first time in the general election of September 1965. A controversial replacement for the great patriarch and disliked by many in his own party, he nonetheless enjoyed wide popular support for his role as economics minister during the “economic miracle.”60 Arguably the Games offered a chance to follow through on his election campaign and consolidate his image as the “people’s chancellor” (Volkskanzler).61

Ideological reasons, of course, would have featured in Erhard’s thoughts too, not least the notion of a formierte Gesellschaft (“aligned society”), which had been introduced at the CDU’s national conference in 1965. In Erhard’s view, West German society was increasingly driven by the dictates of consumerism and performance, the competition within the pluralist system neither catering for the individual nor contributing sufficiently to the common good.62 As a diffuse concept aimed at recalibrating such developments, the formierte Gesellschaft would wither quickly on the vine but, having been underscored three weeks earlier in his declaration of government, the idea would have been lodged in the chancellor’s mind when the Munich delegation arrived in Bonn. A successful bid would provide the ideal opportunity to stage a grand and dignified occasion that would demonstrate the cohesion of German society, its public spirit and a belief in nonmaterialistic values.63 Furthermore, Erhard would have been keen to capitalize on the noticeable shift that had occurred in West German identity by the mid-1960s—away from the 1950s’ projection of a reunified nation toward an acceptance of the status quo of the Republic’s economic and democratic strength. The formierte Gesellschaft, which breathed contemporary theory’s optimism about technology and social engineering, sought to orientate the Federal Republic firmly toward the future. Hosting the Olympic Games would rearticulate for audiences at home and abroad another major claim of his declaration of government: that the postwar era had now “ended.”

Such was the chancellor’s mindset as he took the matter to the cabinet on 2 December. Although full cabinet minutes have not yet been released for this period, a short protocol affords some insight into how the discussion unfolded. The meeting was certainly not unanimous, opinions—where recorded—splitting along party-political and regional lines. CSU voices (Richard Stücklen, Richard Jaeger, and Werner Dollinger—the first two from the Munich region) backed the chancellor, while CDU and FDP members (Rolf Dahlgrün, Jürgen Seebohm, Hans Katzer) urged caution. Dahlgrün (the FDP finance minister) estimated the cost at DM 1 billion, more than double Vogel’s projection (the final bill would come to twice that again), and Seebohm (the CDU minister for traffic) noted that the Bund faced other pressing infrastructural obligations. Stücklen (minister for mail and communication and MP for Dachau) and Jaeger (minister for justice and MP for Fürstenfeldbruck), by contrast, played the national prestige card, arguing that “cost should not be the main priority” given the “extraordinary political importance” of hosting the Olympics “thirty-six years after the Berlin Games.”64 Just as Strauß had argued two days earlier in the Bundestag, Bavarian politicians in the cabinet pushed the case for Munich, and by extension their region, on grounds of national representation. As the cabinet fell in-line with the chancellor, this particular pattern of influence and loyalties was set for subsequent governments, when strong regional ties would cross party boundaries.

That said, the preparation for the Games would be characterized by a general unanimity of purpose between city, Land, and Bund, despite inevitable and sometimes petty tensions that occasionally arose. Bavaria would seek, largely in vain, to gain advantage over Munich: in early 1966 the names of three CSU MPs—Konstantin von Bayern (a member of the Wittelsbach family), Hans Drachsler, and Franz Josef Strauß (who had just refused a position in Erhard’s cabinet)—were floated as the potential “federal and Bavarian Olympic representative” to serve at the helm of the OC before it was established that IOC statutes gave exclusive organizational rights to the host city and National Olympic Committee (i.e., Vogel and Daume).65 Likewise, Konstantin von Bayern would continue to bait Vogel with independent CSU-driven funding initiatives (the so-called Flammenpfennig) until brought to heel by the overwhelming power of the OC.66 Vogel, for his part, tried to preserve Munich and SPD interests, failing most prominently perhaps to elevate a member of his personal staff in the city hall, Camillo Noel, to head of the Games’ press office against a better qualified and well-connected applicant.67 (The successful candidate, Hans “Johnny” Klein, had worked for a number of newspapers, acted as press attaché at German embassies in the Middle East and Indonesia, and been part of Erhard’s 1965 election campaign and chancellery.) On the whole, however, the Munich Olympics stand as a clear example of “cooperative federalism.”68 Despite a highly decentralized administrative and executive system, the SPD-governed city, the conservative-run Land, and three different federal governments conducted their business largely unswayed by political differences. Technically too, the ten-man board of the OC would be set up so that the political partners assumed a distinct common identity: in a system that required a two-thirds majority, the four votes belonging to those bearing financial responsibility for the Games granted the politicians a “veto-minority” against the six representatives from the world of sport.69 Generally, however, sport under Daume did little to upset the equilibrium between the political camps.70 The 1972 Olympics was a “mega-event” (M. Roche) that none of the three agencies could shoulder on its own or, for that matter, in partnership with only one of the others. Success, from which all of them would benefit, depended on each of them pulling together.

Munich’s chances were boosted enormously when Vienna pulled out after the Austrian government refused to underwrite its finances.71 As the capital city of a neutral European country that had yet to host the Summer Games, it would have been the strong favorite. But Munich still faced stiff competition, not so much from ill-starred Detroit, which was submitting its seventh application, but Madrid and Montreal. The former could bask in the reflected glory of Europe’s dominant soccer team (Real Madrid), while the latter enjoyed the prestige and organizational advantages of hosting the upcoming 1967 World Fair. In April 1966, however, the German performance in Rome was a tour de force. Munich’s promise—as originally laid out in its bid document and elaborated over the subsequent months by a small group around Vogel—of spatially compact Games that aimed at a Coubertinian synthesis of culture and sport struck a chord.72 The general desire for a return to “humane Games within reasonable limits,” as Vogel reiterated in subsequent years, seemed acute amongst IOC members.73

Munich ranked top in the IOC’s consultations with the international sports federations and, at a time when technical professionalism had not yet become standard practice, excelled with its presentation.74 Three years previous, Buenos Aires’s bid for the 1968 Games had foundered on basic errors that earned the city a paltry two votes.75 Munich, by contrast, left nothing to chance, all elements coming out “a class ahead” of the competitors.76 On the Foro Italico, the Bavarian capital produced a convincing exhibit of its projected venues. Although these bore only a passing resemblance to what was later built, the fact the council had already passed a development plan and held an architectural competition for a stadium (unlike the Spaniards whose model was a simple replica of Barcelona’s Nou Camp) proved vital in demonstrating the city’s intent.77 The Germans exploited modern methods of communication, investing around forty thousand deutschmarks in a carefully scripted film Munich—A City Applies. For fifteen minutes the inhabitants of Munich, young and old, were depicted as sports enthusiasts with active lifestyles; the city’s rich artistic, cultural, and architectural heritage was highlighted; its love of folkloric traditions such as the Oktoberfest flaunted; and its self-proclaimed image as a “metropolis with a heart” (originally dreamed up for its eight hundredth anniversary in 1958) trumpeted again. Playing on IOC members’ penchant for luxury and scenic locations, the film emphasized the city’s experience in hosting international conferences, blending in the baroque palaces of Nymphenburg and Schleißheim for visual finesse.

After Montreal had overrun, Vogel and Daume ostentatiously shortened their speeches, taking just a few minutes to highlight the main features of the document already sent to committee members in February.78 It turned out to be a convincing effort. Having topped the first round with a good third of the sixty-one possible votes, Munich eased to the total of thirty-one required for an overall majority after Detroit dropped out and its eight votes were redistributed at the second stage. Madrid (sixteen votes in the first round, fifteen in the second) and Montreal (sixteen, then thirteen) failed to pose the serious threat that many had feared.79

FIGURE 2. Special announcement by the local Süddeutsche Zeitung: “Munich is an Olympic city,” April 1966 (photo: Fritz Neuwirth, courtesy of Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo)

Before the outcome was known, Vogel thanked the rival cities for the fairness with which the competition had been conducted, but the spirit of his remarks was not entirely clear.80 At its 1964 session in Tokyo the IOC had explicitly forbidden applicant cities from making “special approaches to the IOC either in person or through diplomatic channels”; the giving of presents had also been outlawed, not least in reaction to rumors of bribes involving prostitutes that had helped Tokyo itself win the Games at the 1959 session in Munich.81 However, Vogel’s Montreal counterpart Jean Drapeau had conducted a worldwide tour of IOC members and pledged free board and lodging for participants at the Games (as opposed to the subsidized fee of US$6 per day offered by Munich)—a promise, in Daume’s words, that “would have had de Coubertin turning in his grave.”82 And while the Spaniards lacked funds, the shadow of withdrawal having hung over their bid from early 1966, they matched hard currency with political capital. Ironically, given Franco’s dictatorship and the only recently lifted ban on citizens from communist states entering Spanish territory (1962), Madrid portrayed itself “grotesquely” (as Daume later recalled) “as a stronghold of freedom and democracy,” playing on the West Germans’ recent difficulties over East German transit issues (see chapter 6) and guaranteeing free movement to athletes from the GDR.83

Before leaving for Rome, Vogel had stressed that Munich had adhered “absolutely to the letter” of IOC rules.84 But it is clear that the Germans had not been so naïve.85 At the first opportunity, Vogel had written to Brundage stressing that Munich “would make special efforts to ensure that IOC members and their families enjoyed the pleasures offered by [the city] and the surrounding area.”86 IOC dignitaries were duly invited, for maximum discretion by the German Olympic Society rather than the organizers, to stop over before the session in Rome.87 He announced his intention to visit Brundage in Chicago (see chapter 3) and massaged the president’s prejudices, congratulating him for his (even then outmoded) stance against the abuse of the Olympic Games by business interests.88 Despite being an outspoken critic of the IOC’s strict amateur guidelines, Daume went even further. Shortly before Rome, he persuaded figure skaters Marika Kilius and Hans-Jürgen Bäumler to hand back the silver medals they had won at the 1964 Winter Olympics on national television. Darlings of the German public, the skaters had been disqualified by the IOC for signing professional contracts with Holiday on Ice before the Innsbruck Games began.89 By returning the medals of their own accord, the whole affair, which had caused a storm throughout 1965, came to a convenient end.90

Behind the scenes, too, a working party—consisting mainly of city administrators, Walther Tröger (a National Olympic Committee member who later became mayor of the Olympic village) and representatives of the Land and Bund—was set up in January 1966 to “prepare suitable measures for the representation of the Munich bid.” One of its main objectives was to create a positive mood in the international sports press.91 Bruno Schmidt-Hildebrand, a member of the city’s public relations department and head of the Munich-based Association of the German Sports Press (Verband deutscher Sportpresse), exploited his connections in the Association Internationale de la Presse Sportive (AIPS), regaling twenty opinion-makers across Europe with the autonomous sporting aspect of the application and the “dynamic personality” of the young mayor. In a spurious twist to the bid’s major tenet, he claimed the Games were not intended “to show the world the new Germany [or] . . . to present the new German youth.”92 Journalists were invited on three-day information-gathering visits to the city, where they were received by the mayor and other officials and treated to first-class accommodation, tours, and tickets to the opera. In the months leading up to Rome, so many invitations were accepted that the visits had to be staggered to avoid arousing suspicion.

Western journalists featured in the program and those with potentially hostile IOC members were especially courted. Because of concerns about British member and International Amateur Athletics Federation (IAAF) president David Lord Burghley, the U.K. press alone received three invitations. Widely tipped to become Brundage’s successor, Burghley was regarded as a GDR-sympathizer because of the IAAF’s recognition of the East German athletics team in 1964.93 But for obvious reasons, the working party’s main interests lay beyond its natural Western allies. Given that Eastern bloc members were likely to vote against the Federal Republic, great effort was invested in the “Third World.” For although IOC members acted as ambassadors from the committee to their respective nations and not—as in normal international nongovernmental organization practice—vice versa, Daume knew that representatives from developing countries would vote in-line with their government’s wishes.94 Accordingly, West German emissaries were sent around the world with the informal authority to make promises of financial aid to enhance such countries’ preparation for the Games.95 The trips alone cost the Foreign Office Cultural Fund around DM 50,000.96 Nonetheless, the working group was cautious about flaunting its official backing, since exerting influence via diplomats could prove counterproductive. Burghley himself reacted petulantly to an approach on Munich’s behalf by Aubrey Halford MacLeod, British Ambassador to Iceland and former general consul in Munich (1960–65), promptly announcing his support instead for little-fancied Detroit, which had missed out on hosting the 1968 Games by a single vote.97 Naturally, the Foreign Office offered support, embassies and consulates being asked to observe the visits and spy on rivals.98 But in general, high-ranking sports functionaries with untainted political reputations and good contacts in the relevant countries were preferred for the task. Such considerations were particularly important in Africa because of Germany’s colonial past. Surrogate diplomats included Max Danz, the president of the West German athletics federation and a vice president of the West German NOC, and Alfred Ries, a Jew persecuted by the Nazi regime with impeccable credentials for representing the Federal Republic abroad: not only was he president of Werder Bremen soccer club and a board member of the German Soccer Federation, but had served as ambassador to Liberia under Adenauer before becoming general manager of the major German coffee company Kaffee Hag.

Danz concentrated on South America, Ries mainly on Africa. While cultural reasons alone dictated that the eleven members from South America (including Cuba) would probably vote for Madrid, positive responses from the two Brazilian members João Havelange and General Sylvio de Magalhães Padilha gave a glimmer of hope.99 The German embassy in Buenos Aires also brought Bonn good news, reporting that Argentine member Mario L. Negri had expressed “full sympathy” to the cause.100 The prognosis for Africa, however, was much more favorable from the outset. Unlike ten member states of the Arab League (including Syria, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt), Morocco and Tunisia had maintained diplomatic relations with the Federal Republic after its formal recognition of Israel in 1965; and—with the exception of the apartheid regime in South Africa—the poverty of the remaining nations (e.g., Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal, West Sahara) would make them amenable to persuasion.

In the age of decolonization, Africa had rapidly become a theater of superpower struggle over ideological allegiances and the new economic world order. In view of its growing fiscal strength, the Federal Republic was called upon to “accept greater responsibilities and an increased share of the burden for securing the future of the Western alliance. . . and the development of the Third World.”101 In this context, the term cooperation concealed a myriad of intricate and duplicitous power relations between first- and third-world countries, the latter exploiting the former, as much as vice versa, and “demanding ever more [development aid] as the price” for their loyalty.102 The realm of sport was no exception. If in the run-up to the 1972 Games the Federal Republic educated athletes from countries sympathetic to the West—almost 10 percent of students at the Sporthochschule in Cologne came from abroad in 1970—the GDR followed suit at the College for Physical Education in Leipzig; if the Ministry of the Interior sent West German coaches to train soccer players in Senegal, Ghana, Cameroon, Mali, Ivory Coast, Togo, and Uganda, the GDR did likewise by dispatching physical education teachers to the Middle East, Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa.103 If the Soviet Andrianow wanted to expand the power of the socialist bloc by democratizing the IOC and giving representation to all NOCs, Western sport functionaries like Daume did everything in their power to prevent it. Sport, therefore, was a keenly contested subfield of the Cold War “fight for Africa.”

When it came to securing the success of the Munich bid, the Federal Republic’s surrogate diplomats were bolstered by President Heinrich Lübke (CDU), a hard-line opponent of East German recognition.104 Set to embark in early 1966 on a tour of Morocco, Kenya, Madagascar, Mali, Togo, and Cameroon (the latter two with former colonial ties to Germany), the president agreed to canvass the relevant local authorities. Only Morocco had an IOC member, but the Munich team hoped for a ripple effect across an African continent famous in the 1960s for its love of sport. In Morocco, Lübke secured King Hassan’s support against the ongoing GDR campaign to “reinforce the division [of Germany] in the realm of sport” but left the question of the bid open, since the monarch was keen to cultivate equally good ties with Spain.105 However, by the time Danz arrived a week later, Moroccan IOC member and high-ranking Muslim cleric Hadj Mohammed Benjelloun assured him not only of his country’s vote but of his determination to bring his colleagues from Tunisia, Senegal, and Egypt on board.106

While it is impossible to say how individual votes were cast, it is likely that the combination of presidential influence and surrogate diplomacy had a considerable effect on the outcome in Rome. Pressed twice by the Foreign Office in the following months to divulge the secrets of the voting chamber, an initially reluctant Daume “was strongly convinced that all Africans . . . from north to south without any exception whatsoever” had supported Munich. With success, Daume noted, came “responsibilities, the fulfillment of which would be of eminent political value for the Federal Republic.”107 The Foreign Office clearly agreed. In 1969, Daume was able to diffuse Vogel’s fears about threats of an African boycott over the participation of Rhodesia and South Africa in 1972, bullishly assuring the mayor that the Africans had just picked up “a fat check from the federal government” and were turning down invitations from the Eastern bloc.108 Foreign Office figures certainly bear him out. In the run-up to Munich, sport development aid for “third world” countries increased steadily as a part of foreign cultural policy. The total expenditure of DM 685,000 in 1966 rose to nearly DM 1.2 million in 1970 and, including DM 500,000 for the preparation of athletes for the Munich Games alone, DM 1.8 million in 1971. Originally, DM 2.43 million and DM 2.95 million had been earmarked for 1971 and 1972, though these figures were later reduced as part of general cuts in the 1971 federal budget.109

Compared to West Germany’s official development aid, which was funded by the Economics Ministry and ran into the hundreds of millions per year (e.g., DM 600 million in 1965), these were small sums.110 But developing countries sympathetic to the Federal Republic’s representational claims, as Lübke stressed all the way across the African continent in early 1966, could, of course, hope to receive from the bigger pot as well.111 Despite complaints from Rabat that development aid and military equipment had been slow in arriving, the Federal Republic paid large sums to keep African nations onside.112 Even before Lübke’s visit, Morocco had been offered almost DM 194 million for the next several years.113 As Heide-Irene Schmidt has shown, West German development policy in the 1960s operated on a fine balance between favors given and received: although “aid was granted according to recipients’ needs” and the Federal Republic “did not expect ‘active support’ . . . in return for aid,” it nonetheless appreciated “mutual respect of national interests as a foundation for co-operation.”114 Thus, when the president assured King Hassan that support for the Munich Games was not a “question of principle,” a subtle but very definite ritual of expectation was at play.115

It is little wonder, then, that Daume’s speech in Rome sold the Munich Games as a bridge not only between sport and the arts, East and West, but also “young” nations and “old” nations.116 In later years, Daume would portray the wooing of African votes as a kind of “social justice.”117 In early 1966, at a time when regional games threatened to lure African countries away from the Olympic movement altogether, the West German NOC president felt able to confide his plans to Brundage: “We have . . . offered—if it should be in agreement with the IOC’s views—to support the young nations in Africa and Asia financially and technically in their preparations for the Games and when they send their athletes.”118 Taken together, the Cold War and decolonization eased the Munich bid toward success. West German money was already flowing into Africa, and with the IOC, the Western allies, and the Federal Republic wanting to hold on to it, the continent was only too open to persuasion.

Such agendas meant that Africa—much more than Asia or South America—remained firmly on the Federal Republic’s radar after the Games were won. Although the organizers could not expect many visitors from the continent, they were keenly aware of a “certain political and sports political obligation to keep [its] population[s] well-informed” about the event.119 By the same token, the Olympics provided the Federal Republic with a much-needed opportunity to enhance its stale and outmoded image in this strategic region of Cold War struggle. In the wake of German colonialism and two world wars, an internal position paper noted, African views of the Federal Republic were still largely shaped by the “masculine . . . soldier, brave both in attack and defense, loyal and adept at using his weapons.” “Self-restraint, unconditional obedience and the prioritizing of honor ahead of other criteria” also determined the picture, with Bismarck and Hitler, for the Arab populations of North Africa at least, appearing the very “incarnation of Germandom.” Across the whole of Africa, moreover, the “un-rhythmical” Germans played second fiddle to NATO allies such as the “sensitive” French.120 Thus the Games allowed for a more positive projection of the German character: namely as “peaceful, conciliatory, serene, sensitive, sober and accurate and looking for harmony.”121 One million deutschmarks of additional funds, donated to the OC by the record company Ariola (equaling some 10 percent of the overall PR budget), were invested in specific advertising initiatives. In particular, the urban middle-classes of the twenty-eight nations with NOCs were targeted in English, French, and Swahili; a highly popular Olympic poster competition was organized for African artists; and the customary activities of the federal agencies and ministries involved in cultural diplomacy were intensified. The Federal Press Office organized seminars for African sports journalists in the Republic.122 Daume hand-delivered invitations to African NOCs, making impassioned speeches about their integral role in the Olympic movement and bearing gifts of material and financial aid.123 In Lagos he handed over DM 1 million to help West African athletes participate in the 1972 Games and a track made of the same material as the one at Munich’s Olympic Stadium.124 Until African solidarity against Rhodesia’s participation strained relations and almost led to a massed boycott in mid August 1972, the Munich Games received hugely positive coverage across the continent and allowed the Federal Republic, via sport and its ever-popular functionaries, to bestow “great honor”—as one Foreign Office report duly observed—on the people of Africa.125

Once the euphoria of Rome had dissipated, the organizers would be tossed between the Scylla of financial burden and the Charybdis of Cold War politics for some time to come. (The latter is discussed fully in chapter 6.) When informed of the bid’s success, Erhard hailed it as a “mark of great distinction” for the Federal Republic.126 Four years later, in April 1970, Genscher, the interior minister of the new SPD/FDP government, captured the chancellor’s original mood at an Olympic exhibit arranged for politicians in Bonn: “This is an historical opportunity to convey a desirable image of this state and the society which sustains it on the occasion of the Olympic Games to hundreds of thousands of international guests as well as hundreds of millions of TV viewers, radio listeners and newspaper readers.”127 From the earliest moment, it was obvious that Munich would be a “national task.” Olympic Games “mean a great deal,” as Willi Daume stressed when inviting the great and the good to join the OC’s advisory council (Beirat), “particularly for the country that gets to invite the youth of the world.”128 But it was not until 1969 that Bonn officially recognized the Games as such. There is a simple reason for this. Federal law dictates that matters of national representation must be financed predominantly by the federal government. The essential difference between Erhard’s reaction in 1966 and Genscher’s speech in 1970 was the vital promise of additional funding: in view of the task’s significance to the nation, Genscher went on to note, the Bund would be carrying “the largest financial share of the investment and organizational costs.”129 This discrepancy between emotional and bureaucratic understandings of the Olympics’ importance made for years of protracted negotiations between the city of Munich and Bavaria on the one hand and the federal government on the other.

In 1965, the head of Erhard’s Kanzleramt and skeptical members of the cabinet had not been alone in their fears about the Games’ funding. Before the bid had passed through the various parliaments, the country’s leading financial newspaper, the Düsseldorf Handelsblatt, published a damning article warning that the three parties were rushing headlong into “an expensive plan.”130 Soon after the success of Rome, five CSU MPs (led by Franz Gleißner) sent an open telegram to Vogel, demanding the Games be stopped to protect essential expenditure on schools and hospitals; they had to be muzzled by the CSU caucus in the city council (under Hans Stützle).131 As soon became apparent, though, the doubters had called it right. A memo from the Ministry of the Interior shows how Daume and Vogel had arrived at the initial estimate of DM 497 million: 158 million were to be spent on the Olympic venues, 120 million on the Olympic village, 3.5 million on administration and organization, and 185.5 million on traffic infrastructure, leaving 30 million in reserve for unforeseen circumstances.132 But by the summer of 1966, the costs had already increased by 23 million, and much steeper rises were to follow. All told, the Games cost DM 1,967 million, just shy of the eye-catching DM 1,972 million later enshrined in the official report.133 Put another way, the checks made out to the Africans had shrunk over six years from 0.6 to a mere 0.15 percent of the total bill.

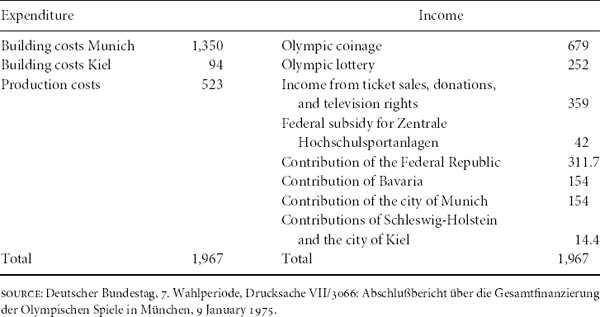

TABLE 1. 1972 Munich Olympic Games’ Expenditure and Income (in millions of DM)

These cost increases were largely caused by local inflation, not least because the event set an absolute deadline for the completion of venues and their supporting infrastructure. In 1965, the Munich Chamber of Trade and Industry warned the Games would lead to an “excessive boom in the construction industry with adverse effects on the makeup of local prices and wages,” a prediction that proved all too accurate.134 Between 1968 and 1973 Munich’s price rises outstripped the national average, and the city became the most expensive in the country by 1971.135

In his study of Olympic finances, Holger Preuss makes a basic but useful distinction between expensive and inexpensive Games. Olympics tend to be “cheap” if, as in the two most recent North American examples (Los Angeles 1984, Atlanta 1996), “costs are largely limited to organizing and staging the Games” with profits made or deficits avoided by exploiting existing infrastructures. Games work out to be expensive, by contrast, if they require “extensive investments in traffic infrastructure, communication systems, housing and sports facility construction.”136 On the surface, 1972 fits the second category, but the actual costs, when compared to other Games of the period, place it some way back across the spectrum. The figures for Rome 1960 and Mexico 1968—doubtless for good reason—were never published. But Tokyo 1964 cost US$2.8 billion at a time when one dollar bought four deutschmarks and Montreal 1976 made a colossal loss, with Mayor Drapeau spending like “a Roman Emperor” and allowing costs to soar from an estimated US$300 million to 2.8 billion.137 Famously, the Canadian government declined to contribute from the outset, leaving the taxpayers of the city and the province of Quebec to struggle with debt until 2006.138 Munich’s total of US$500 million—less than the price of two aircraft carriers, as Richard Mandell trenchantly observed—paled by comparison.139

In point of fact, the Games represented extraordinary value for money.140 In the end, only DM 634 million (i.e., 142 million more than anticipated in the original estimate) came from the three public coffers.141 Munich city’s total expenditure of 154 million, around DM 20 million per year from 1966 to 1972, equated to less than 1 percent of the municipality’s annual budget in 1970.142 Apart from shrewd and—as time went on—forensic financial management, the fiscal health of the Games benefited from several crucial factors.

First, between them the organizers already owned a largely undeveloped site approximately twice the size of Munich’s historic city center. The Bund immediately declared itself willing to remove its army barracks and virtually no costs were incurred for relocating businesses.

Second, the Games drew on unorthodox and inventive methods of financing, the single most important revenue stream coming from coinage. From 1969 onward, 100 million ten-deutschmark silver coins generated DM 679 million in revenue—some 34.5 percent of the cost of the Games and more than the combined contribution of the city, Land, and Bund. Initial fears about inflation were unfounded as the West German public avidly snapped the coins up, keeping them for posterity rather than spending them as currency. Inspired by a similar venture at the 1968 Games, the scheme enjoyed unprecedented success, not least when the Eastern bloc protested the wording “Games of the Twentieth Olympiad 1972 in Germany (Spiele der XX. Olympiade 1972 in Deutschland)” (rather than “in Munich”)—a debacle that turned them into a collector’s item.143 An Olympic lottery, established in 1967, brought in DM 252 million, while its television equivalent, the Spiral of Fortune, which played off the Olympic emblem and was supported by high-profile guests such as Franz Beckenbauer and Avengers star Patrick Macnee (in Bavarian dress!), produced DM 187.6 million between 1970 and 1972.144

Third, the Games pushed commercialization up to and beyond the legal limit. The 1972 Olympics were the first to be regulated by a specific contractual agreement between the IOC and the host city about the distribution of television revenues, which had been rising rapidly since the first substantial screening of the Games in Rome 1960. The Germans not only quadrupled the sum procured by Mexico City (receiving US$13.5 million from ABC) but—much to the ennui of the IOC—also maximized their share by arguing that equipment and technical costs should redound directly to the hosts.145 More importantly, deals with leading companies and the sale of commercial rights to the Games’ emblem generated significant (although largely undisclosed) sums. Falling through the cracks opening up between ambiguous IOC statutes and the burgeoning spirit of free enterprise in sport, such arrangements had been commonplace for several Olympics, and Munich was well placed to take advantage. In the Society of Sponsors, which had liaised with local industry and commerce since 1955 to help finance the city’s future “major stadium,” the organizers could exploit an existing fund-raising apparatus. Renamed Olympic Sponsors Association in 1966 and working closely with the OC, the society collected some five hundred promises of consumable donations and loans of equipment. In addition to the companies mentioned earlier, a host of household and local names lent their support. From Kodak to Wella AG, companies donated everything from television sets and hair salons to petrol, toothbrushes, and, in the case of Franz Zimmermann KG Nittenau, five tons of German chicken. The total savings for the organizers—none of which appear in the final table of costs—amounted to a staggering DM 300 million in loans and around DM 48 million DM in cash donations (i.e., the equivalent of almost one-fifth of overall actual expenditure).146

After the IOC’s lucrative capitulation to television and commerce in the 1980s, this financing of Munich might seem arcane. But for the 1960s and 1970s, Munich was superlatively managed. Unfortunately for the organizers, though, this was not apparent at the time. The first ten-deutschmark coins were not minted until 1969, the scale of their success only filtering through over the following years; and lengthy negotiations meant that the television contract with ABC was not signed until 1969, despite the OC having to pay out annual advances of DM 500,000 to Lausanne from 1967.147 In other words, as costs began spiraling at an early stage, the OC and its political backers had a difficult battle on their hands.148 Their struggle was inevitable from the beginning, since Erhard’s government had cloaked its original assurances in a straightjacket. When the Bundestag’s powerful budget committee (headed by Vogel’s SPD colleague, Erwin Schöttle) agreed to bear one-third of the estimated cost, it did so with important provisos: all alternative avenues of funding were to be explored and, crucially, the cost-sharing formula was to be renegotiated should the total sum exceed DM 168 million.149

If Bavaria played a relatively minor role in the bid, it was to come to the fore in the fight for funding. In times of increasing tax revenues, it could probably have afforded the expenditure, even if this was not widely acknowledged. But standing, perhaps, to gain the least of the three partners, it guarded its purse strings tightest, and in so doing benefited not only itself but the city of Munich as well. As costs rose in the summer of 1966, Bavarian Minister-President Goppel pressed Erhard in vain to reconsider the ungenerous nature of Bonn’s fiscal conditions.150 His successor Kurt Georg Kiesinger, who led the Grand Coalition government from December 1966 to 1969 with Bavaria’s Franz Josef Strauß as finance minister, brought some relief, however. In a consortium agreement of 10 July 1967, Bonn agreed to bear one-third of the real construction costs of the Olympic venues, the contract containing an apparently convenient subclause for the impecunious city and Land, which stated that it should be renegotiated if the actual cost exceeded DM 520 million.151 Given the deal did not actually commit the Bund to further expenditure, however, this caveat proved a mixed blessing.

It was not long before the funding issue became acute. In February 1968, little over six months after the agreement was signed, the OBG revealed that the cost of the Olympic venues had risen to DM 820 million.152 The announcement shocked Bavaria, a Land that had historically required heavy subsidy from the center and been in net receipt of the federal equalization of burdens for a large part of the postwar period. Not surprisingly, opposition grew. On 21 March, CSU deputies in the Bavarian parliament tabled a motion to limit building investment from public funds “to the absolute minimum” and in future reject all “uneconomical proposals.”153 The reasons for cost increases were complex, but not surprisingly Behnisch and Partners’ futuristic tent roof served as a lightning rod for public and political discontent. In 1967, the Stuttgart firm’s idea of draping a Bedouin-style cover made of Plexiglas over the Olympic stadium and nearby sports halls had impressed the architectural jury with its boldness of vision (see chapter 4). But in practice its construction entered uncharted territory in building technology, and costs rose tenfold from DM 15 to 18 million to 188 million, for only half the stadium.154 The dramatic nature of the overall price increases and residual doubts about the aesthetic fit of a modernist design in an architecturally conservative city formed a political powder keg.

A former property developer from Bayreuth (Franconia) who had made his money in concrete, Bavarian finance minister Konrad Pöhner was considered an authority on construction. Sensing how things might develop (the full extent of the roof inflation would only become clear the following year when it hit DM 37 million in spring and DM 130 million by the end of the summer),155 he broke ranks with his colleagues on the OBG, publicly lambasting the modernist roof and suggesting that Munich should withdraw from hosting the Games.156 His deputy, Staatssekretar Anton Jaumann, attacked the extraordinary expenditure, too, in a widely publicized speech in Parsberg/Oberpfalz in the Bavarian provinces. Whether Pöhner and Jaumann were genuinely scandalized or set out merely to score political points against their SPD rivals in Munich, siding with the region’s concrete lobby against the architects from Baden-Württemberg, the city soon responded by accusing Bavaria of mounting an “anti-Munich campaign.”157 Once again, Hans Stützle of the city council’s CSU caucus was called upon to calm troubled waters. Daume intervened with Goppel too, reminding him of the long-term benefits and stressing the crucial importance of Behnisch’s architecture “as a yard-stick to measure the spiritual integrity and credibility of a new, young and democratic Germany.”158

This fracas over, the Land and the city closed ranks again, the former in particular impressing on the Bund that it stood to gain most from the Games. In May, Jaumann wrote to Strauß as chair of the CSU, preparing the way for Goppel to approach Strauß, Kiesinger, and Ernst Benda (minister of the interior, and therefore responsible for sport) in July with a request to renegotiate a 50–25–25 split.159 In the same month, the Munich City Council passed a similar resolution.160 But the parliamentary budget committee rejected the requests, taking the view—expressed by several CDU representatives, most notably Heinrich Windelen, an MP from Lower Saxony—that it would be “inappropriate for the Federal Republic to stage the most lavish Games of the [twentieth] century.”161 Hoping nonetheless that the Bund would relent at some point and assume 50 percent of the overall burden, the city and Land would repeat their arguments mantra-like over the next few years.

Despite Strauß’s innate desire to help his native Land and the emotive pressure of CSU colleagues who appealed to him to respond “with his Bavarian heart,” un-conducive economic conditions and long-term structural changes to federal funding mechanisms dictated that he could not give in.162 In light of the first economic downturn in the history of the Federal Republic in 1967, the dramatic announcement about cost increases in 1968 came at an inopportune moment. Although the economy was to rally again soon, returning by the end of 1969 to growth rates reminiscent of the 1950s, additional federal expenditure on what many saw as a one-off spectacle would have been impossible to sell to the West German taxpayer. As late as July 1969, even the Bavarian section of the German taxpayers lobby wrote to express its grave concerns about the consequences of the Olympic cost explosion.163 Moreover, Strauß felt embarrassingly misled about the roof. As minister of defense, he had normally doubled the estimates presented to him by civil servants and weapons experts and prided himself on the accuracy of his figures. When it came to the Olympic roof, however, this simple algorithm broke down, Strauß agreeing with Vogel that it was the worst case of public price inflation he had ever encountered and pointing out to the OBG board that the press took them all for “philistines, inexperienced lawyers, and bureaucrats who thought in terms of finance and had no idea of the demands of aesthetics.”164

Strauß’s deliberations would have been complicated further by the final negotiations over the federal Finance Reform Law of May 1969, which required a change to the Basic Law (Art. 91a, b) and represented a compromise deal between the municipalities, regions, and the center. Throughout the 1960s in a struggle over the financial muscle of federalism, the three agencies had argued about their respective powers to raise, spend, and distribute public funds.165 Essentially, the regions, communes, and Bund had traded off over the right to maximize financial autonomy and manage “shared responsibilities” (Gemeinschaftsaufgaben) such as health and education. It did not help Munich’s case that the greatest intransigence in these negotiations came from the Bavarian government and Munich’s Hans-Jochen Vogel, who was regarded as the communes’ outstanding expert on financial matters.166 With his dogged persistence on issues of Olympic and urban finance, Vogel became the object of a joke in government departments, to wit that it was “best to avoid mayors from Munich when they were in Bonn.”167 Even in 1971, two years after the passing of the reform, Vogel was still on the urban warpath, addressing international audiences about the need for increased devolvement of fiscal powers to cities.168

FIGURE 3. Signing of the consortium agreement on the financing of the Games between representatives of the city of Munich (Hans-Jochen Vogel, second from right), the state of Bavaria (finance minister Ludwig Huber, third from right), and the Federal Republic (interior minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher, fourth from right) on 29 June 1972 (photo: Fritz Neuwirth, courtesy of Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo)

Nonetheless, calls for a redistribution of costs were beginning to reverberate around parliament. In June 1968, a question-and-answer session in the Bundestag (instigated by Josef Ertl, an FDP MP from Bavaria) had indicated that the majority of parliamentarians were in favor of a new settlement.169 Moreover, parliament’s special sports committee—set up in the final stages of the Grand Coalition government to discuss a range of questions dealing with sport and society, the 1972 Games, and the 1974 FIFA World Cup—concurred. For the rest of 1969, this committee’s meetings were dominated by cross-party lobbying from Munich and Bavarian MPs.170 Finally, in the last days of the Grand Coalition, Strauß gave way. Informing Bavaria and Munich in advance, he held out until after the SPD’s election victory before giving his ultimate consent and left his successor Alex Möller to deal with the consequences.171 Despite Brandt’s reference to the Games as a national responsibility in his declaration of government in October 1969, Möller hardly rushed to pick up the bill. Although Vogel and Pöhner were invited to Bonn for summit talks in December 1969 and given verbal assurances that the Bund would cover 50 percent of expenditure, the budget committee continued to withhold its consent until almost a year and a half later, with the federal parliament itself not able to vote for a redistribution until April 1971. The final consortium agreement was settled on 29 June 1972, just eight weeks before the Games began. Much to the chagrin of Otto Schedl, Pöhner’s successor as Bavarian finance minister, and Munich’s city treasury, the Bund took an inordinately long time to clear the debts it had accumulated over the previous five years.172

Aside from finance, the differences between city, Land, and the federal center were mainly academic. As it transpired, the city of Munich enjoyed a glowing reputation with visitors from abroad, and this would be most valuable to the cause of national prestige. The Federal Republic certainly gained as much from Munich’s international radiance as Munich profited from Bonn’s belated financial munificence. In fact, the choice of Munich as the West German host, rather than rivals with little international profile (Hamburg or Frankfurt) proved extremely serendipitous. When it came to it, the lavish expenditure on architecture and design led the OC, under pressure from the political agencies, to make budgetary cuts, leaving its PR department with only DM 10 million. Astonishingly, a project with a potential worldwide audience of one billion could draw on only 0.5 percent of the overall budget.173

Formulated in January 1969, the OC’s publicity campaign had three obvious goals: to “win friends for the Federal Republic”; to use the “unique occasion” of the Games to “refine or, where necessary, correct the image” of the nation abroad; and to increase West German tourism revenues by encouraging foreign visitors to spend time in the country as a whole.174 Quite apart from pragmatic considerations—such as ensuring that every event in the Games (no matter how obscure) played to a capacity stadium, or siphoning visitors away from a host city short of hotel accommodation—this third objective sought to use the Olympics as a magnet for every part of the Federal Republic. However, if the stated aim of the organizers’ strategy was to “attract as many visitors as possible from as many countries as possible to Munich and Germany,” the reality of budgetary constraint reduced the ambition.175 In short, the PR department was forced to target specific groups and do so, largely, on the basis of existing information.176

Going on statistics from the 1960 Olympics in Rome, the organizers deduced that 50 percent of visitors to the Games were likely to come from four or five countries: the United States and Canada (in the case of Rome, 18 percent), Germany, France (12 percent each), and the United Kingdom (11 percent). North Americans’ commitment to Olympic tourism was underlined by statistics from Tokyo and Mexico City, where they had also formed the largest visitor group, and tourist board records for Bavaria and Munich in 1966 and 1967 pointed in the same direction. While the vast majority of overnight guests in the Land originated within the Federal Republic (22 percent from within Bavaria itself, 71 percent from other federal states), one-fifth of the remaining 7 percent came from the United States and Canada. Figures for the city of Munich itself showed a similar breakdown.177 Boxed in financially, the Munich organizers thus developed an advertising strategy that functioned along Darwinian lines: with the politically determined exception of Africa, only those regions that could guarantee a high yield of tourists were targeted. Latin America and other poorer regions of the world were mostly neglected until relatively late.

The organizers devoted their energies to changing perceptions of Germany in their key target areas of Western Europe and the North Atlantic. The U.S. market was especially attractive because of the high disposable income and spending habits of its Olympic tourists. But while U.S. citizens were believed to respect West Germany’s technical and economic achievements after the war, they did not seem to hold the country in any great affection. This “quasi-neutral” stance would need to be corrected by the production of a “more colorful” picture of Germany. Nevertheless, the United States offered reasonably fertile territory, the author of a report on the OC’s participation in the New York Steuben parade less than a year before the Olympics claiming that he “could not discover any reservations about the Games taking place in the Federal Republic and in Munich specifically” and reporting the assurances of the editor-in-chief of Aufbau, the German-Jewish émigré daily, that his paper would do all it could to make them a success.178 Western Europe, despite new allegiances and alignments in the Cold War, proved a trickier prospect, however. While the overall concept of the Games—with its serenity, modesty, and humane dimensions—would probably prevent audiences in Western Europe from “suspecting [the country of] relapsing into totalitarian mentalities,” there was still much work to be done.179 France, for instance, perceived its neighbor’s post-1945 manifestation as “nouveau-riche, perfectionist and emotionally cold.”180 There, as in Britain, it was considered best to address the younger generations, who displayed “a more flexible and partly more positive attitude to the Federal Republic” than their elders who had direct experience of the war. But while the French and other Western European audiences could be seduced by references to culture and folklore, “umpa music and Lederhosen” were to be downplayed in the United Kingdom to avoid negative stereotypes.181

Munich itself had much to contribute to this effort. A 1969 Infratest poll showed that the city was held in such extraordinarily high esteem by U.S. t ourists—concerns about unfriendly service in hotels and restaurants notwithstanding—that it clearly offered the best hope of correcting negative or value-neutral aspects of Germany’s image as a whole.182 The transfer of Munich’s inherent charms (“metropolis with a heart”) and the texture of its Olympics (“the serene Games”) to the Federal Republic in general, therefore, became a major feature of the PR strategy.183 Thomas Clayton Wolfe, whose praise of the city came to be cited as often as that of Thomas Mann, reflected on the Bavarian capital in his 1939 novel The Web and the Rock: “How can one speak of Munich but say that it is a kind of German heaven? Some people sleep and dream they are in Paradise, but all over Germany people sometimes dream that they have gone to Munich in Bavaria. . . . The city is a great German dream translated into life.”184 The 1972 PR campaign sought to exploit such images, turning them inside out and mapping the city’s charm and allure onto the country as a whole.185 Although not reflected upon by the organizers, the untroubled nature of Munich’s relation to the past certainly made their task easier. Even today, the city lacks an adequate memorial to its complicity in the Third Reich, and in the 1960s and 1970s, its self-image was embedded between the regional and the global. After 1945, Bavarian historiography distanced itself from “Prussian” militarism and focused on the region’s European and cultural connections, while from the 1960s, generations of Munich schoolchildren were presented with the tellingly titled book München. Heimat und Weltstadt (Munich: Hometown and Metropolis).186 Similarly, lectures later given to the Olympic hostesses in preparation for dealing with the public at the Games would skirt around the Nazi era and concentrate on local traditions.187

The main Olympic brochure, In the Middle of this City, published in fifteen languages with a print run of 1.5 million, exemplifies the transfer strategy very clearly.188 Lavishly illustrated, it led its readers out in concentric circles, from the Olympic stadium to the furthest reaches of the Republic. From the building site on the Oberwiesenfeld where, as a sign of the city’s openness, tolerance, and cosmopolitanism, “15,000 workers from twenty-three countries” were reported to be creating “a new piece of Munich,” the booklet whisked its audience to the architectural beauties of the historical city center—an opposition that connoted the synthesis of tradition and modernity. From there, via Wolfe’s eulogy, the focus moved to positive associations of the city—its joie de vivre, youth and beauty (represented by the PR model known as the “schöne Münchnerin”), relaxation (beer, Hofbräuhaus), strolling, shopping, and easy-going social interaction. After the arts and cultural festival, which was as much a part of the “grand celebration of 1972” as the Games themselves, came Bavaria, characterized by its cuisine (dumplings, veal sausage, meatloaf, and local delicacies), folklore (Lederhosen, farms), mountains, castles, lakes, and finally—with Kiel’s hosting of the sailing events on the Baltic coast acting as a linchpin—the rest of the Federal Republic. In keeping with the depiction of Bavaria and its capital, the nation-state was represented by the twin achievements of modern technology (Volkswagen, Autobahn) and cultural legacies (Bach and Beethoven, Marx and Mendelssohn, Goethe and Gutenberg, Dürer and Diesel), supported by stunning landscapes (the Black Forest, Rhineland), historic cities (Heidelberg, Cologne), wine, food, and Gemütlichkeit. In short, prospective visitors were being told that Munich’s special atmosphere could be found wherever they went in Germany.