If the smooth initial handling of Munich’s Olympic project resulted from the consensual tone or “deideologization” that characterized West German national politics in the mid-1960s, its execution in finer detail would be troubled by forces of an unpredictable nature before the decade was out. The Mexico Games proved ominous. Were it not for the dubious decision of a thick-skinned government and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to carry on regardless, the 1968 festival would have been ruined by radical politics. On 2 October 1968, just ten days before the opening ceremony, a summer of violent clashes between students and police culminated in the Tlatelolco Massacre, which caused 260 deaths and 1,200 injuries within a stone’s throw of the Olympic sites.1 Exploiting the presence of international journalists, the protesters chanted: “We don’t want Olympic Games! We want a revolution!”2 Once underway, the Games were dominated by politics and are remembered as much for the Black Power salute of the African-American medalists Tommie Smith and John Carlos as for the warmth of the Mexican people and the extraordinary altitude-assisted performances of athletes such as Bob Beamon.

In 1968, of course, revolution was not the sole preserve of Mexican students. Across vast tracts of the Western world, “the cultural eco-system,” as Tony Judt has recently put it, “was evolving much faster than in the past. The gap separating a large, prosperous, pampered, self-confident and culturally autonomous generation from the usually small, insecure, Depression-scarred and war-ravaged generation of its parents was greater than the conventional distance between age groups.”3 In Western Europe, a rapidly expanding education system propelled huge numbers of young people into a tertiary sector hopelessly under-equipped for the speed of cultural change, fomenting discontent. When events came to the boil, they were sustained by a common, heady mix of theory, sexual liberation, and the justification of violent means, but marked as well by distinct local inflections. In Germany, specifically, nascent unease with the older generation’s supposed amnesia about the recent past became acute. Not only did the Mitscherlichs’ psychoanalytical account of the nation’s unwillingness to recognize individual responsibility make it onto almost every student bookshelf (Die Unfähigkeit zu trauern, The Inability to Mourn, 1967), but radical campus leaders vehemently placed the blame on the young Federal Republic, a system they viewed as an anaesthetized, Americanized offshoot of the consumerist West. From the immediate perspective of the Munich organizers, this unexpected return of ideology transformed the 1972 Olympics into contested territory. How exactly were they to organize an event, defined famously since the days of de Coubertin as a celebration for the “youth of the world,” when its chief participants had become distinctly disaffected? And how, in a national context, could “modern Germany” be adequately represented when the country was changing and challenging itself at a rapid rate? These were just some of the questions that faced the Organizing Committee (OC) as it entered its key phase of preparation in 1968.

In retrospect, as Judt also notes, “the political geography of the Sixties can be misleading,” “the solipsistic conceit of the age—that the young would change the world by ‘doing their own thing’ ”—proving ultimately “an illusion.”4 But this does not mean the mood of unrest was not keenly sensed by participants at the time, nor treated with any less urgency by those against whom their actions were directed. It is also clear that the demand for change, at first expressed with belligerent intent, was not immutable but changed itself over time, intensifying in some areas, modulating and dissipating in others. Even if many of the key decisions about the particular form the Games would take had been reached before the events of 1968; even if the mindset of influential organizers proved compatible with the emerging spirit of the age; and even if some of the most aggressive opposition to the Olympics among critical German youth had all but blown out by the late summer of 1972, the ways in which the organizers engaged—fully, partially, or in censorial fashion—with the intellectual and social climate over time is a crucial element in the narrative of the Games. Just as the Munich Olympics should not be reduced to a mere Social Democratic Party (SPD) pageant, it would be misleading to view their relaxed atmosphere simply as a reflex of “1968.” Visitors to the Olympic Park might have been encouraged to “walk on the grass” and “pick the flowers” but, in actual fact, the “spirit of ‘68” stood in complex relation to the Games. The culture of 1968—like the SPD’s election victory with which it was inextricably linked—certainly influenced them, but the ways in which it did so were not always obvious.

In the Federal Republic, as elsewhere, the unrest of 1968 did not alter the system of government. Rather, the experiences of those years condensed, radicalized, and accelerated cultural and lifestyle changes that had been evolving subterraneanly since the beginning of the “long 1960s” in the wake of social and economic developments brought about by the “Golden Age” of Western capitalism.5 Rejecting middle-class parental values, young people espoused a range of alternatives, which invariably involved a renouncement of traditional worldviews imposed from above, the return of ideology in the guise of New Left thought, and increased political participation both within and outside the system of representative democracy.6 Concurrently, the late 1960s witnessed the rise of hedonistic lifestyles among young people, which frequently clashed with the fundamental Olympic tenets citius—altius—fortius and challenged the performance principle (Leistungsprinzip) characteristic of men such as Daume and Vogel.

There is no need here to chart the development of the so-called extra-parliamentary opposition (APO) that crystallized in protest against the perceived hyperconsensus of the Grand Coalition and its emergency laws between 1967 and 1969. But the effects of the troubles on the city of Munich are certainly worth noting. Though not a major theater of confrontation, the future Olympic city was no backwater either. While the frequency and scale of its demonstrations lagged some way behind those in Frankfurt and West Berlin, the “Easter riots,” which erupted after the assassination attempt on Rudi Dutschke in April 1968, took a particularly unfortunate turn in the Bavarian capital. As more than fifty thousand protesters fought with twenty-one thousand policemen across the Federal Republic in the worst episode of civil unrest since the early 1930s, Munich, surprisingly, witnessed the only civilian deaths.7 An Associated Press photographer and a student lost their lives in a street battle in front of the local newspaper distribution center of the right-wing Springer Press in Schwabing, half-way between the city-center and the Olympic venues.8

Although these events were to inform the OC’s approach to the Games, and in particular the security measures surrounding them, the organizers’ main task was not to deal directly with 1968 itself, but rather its complicated fallout among different categories of West German youth. The eventual collapse of the student movement and APO in 1969 led to a spectrum of new political and cultural developments within the younger generation. Generally, these came to be reflected in the Games, either in the concessions the organizers made or, more vaguely, as a result of their attempt to figure out the cohort’s understanding of the Olympics. The developments with which the organizers had to wrestle included the emergence of the so-called K-groups on the fringe, the return of others to conventional political participation, and the readiness of others still—the majority, in fact—to combine a critical but nonradical habitus with the external trappings and hedonistic lifestyles exemplified by the 1968ers.

The organizers were troubled least by the K-groups—such as the KPD/AO, KPD, KPD/ML, and the Basic Workers’ Groups for the Rebuilding of the Communist Party (Arbeiterbasisgruppen für den Wiederaufbau der kommunistischen Partei)—on the far left of the spectrum. Rather than rechanneling their energies into conventional politics or turning to terrorist action like the Tupamaros, the Red Army Faction, or the Movement 2 June—these small sect-like political cells adhered to a variety of views from Maoism and Stalinism to Leninism, Trotskyism, anarchism, and syndicalism, and drew their inspiration from the Russian and Chinese revolutions.9 Devoting themselves to the establishment of authoritarian cadre parties, they waited in readiness for the violent overthrow of the government. While—as we shall see—their demonstrations kept the authorities on their toes during the Games, their overall impact on the shaping of the Munich event remained slight. Much the same can be said of the newly founded GDR-sponsored German Communist Party (Deutsche Kommunistische Partei, DKP) and its youth organization, the Socialist German Workers Youth (Sozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterjugend, SDAJ).

By contrast, a larger imprint was left by the section of the 1968 movement that, in Dutschke’s famous phrase, embarked upon the “long march through the institutions.” In the immediate aftermath of 1968, the SPD saw its ranks swell by tens of thousands of new members—particularly through its youth organization, the Young Socialists (Jusos)—who played an important role in sealing Brandt’s election victory in 1969. Having involved themselves decisively in major political change, the Young Socialists sought to hold the chancellor to his promise of “daring more democracy.” Swept up in this ever-enveloping discourse, the Olympic organizers increasingly inscribed the notion of wider public participation into the blueprint for the Games. In Hans-Jochen Vogel, this offshoot of the 1968 movement could ostensibly count on a sympathetic ear. He empathized with their discontent, reading it as a symptom of the problems of “affluent societies” in the West—a view which affected him throughout his time in office and, most notably, informed his agenda for urban regeneration. Typically, in a speech delivered to students on the Königsplatz a few days after the “Easter riots,” he interpreted the unrest as an anxious reaction to the accelerated development of modernity. As a conservative and pragmatic Social Democrat, the mayor accepted the need for political and social reform while drawing the line at radical left-wing adventurism and the use of violence.10

Not long before the Games, however, this rejection of extreme leftist policies was to impact Munich City Hall directly. Nationally, the Young Socialists had been concentrating on shunting their party back to the unambiguous left-wing position of its pre-Bad-Godesberg days and forcing the newly elected Lib-Lab coalition to implement radical socialist reforms.11 In early 1971, Vogel came under pressure to commit to a radical agenda before the 1972 council elections, when he was likely to secure a third term in office. When difficult negotiations between the left and right wings of the local SPD failed to reach a compromise, Vogel—perhaps with characteristic opportunism—declined to run again at the beginning of 1972, becoming leader of the Bavarian SPD instead and rapidly winning promotion to federal construction minister (Bundesbauminister) in Brandt’s second cabinet after the general election in November.12 He was succeeded in Munich by Georg Kronawitter, another pragmatic Social Democrat, who triumphed in the local vote in June 1972. Thus, just two months before the Games, radical politics were instrumental in removing one of the key architects of the event before his moment of glory. Although retaining his position as vice president of the OC, Vogel attended the Games as a guest rather than an official—and need not, after all, have fretted about appearing on the world stage with Bavarian folk troupes.

Like the K-groups, therefore, the Young Socialists occupied the organizers as the Games were taking shape. But neither formed the primary focus. The former were too marginal or dragonfly in lifespan, the latter, though important, were overshadowed by the sheer transformations in everyday life that were eagerly accepted and pursued by the majority of young people regardless of their political orientation. From the questioning of adult authority to pronounced sartorial and musical choices, a dominant mode of behavior emerged. This large amorphous group of newly invigorated and legitimated youth formed an essential audience for the Games. Without their support, the Olympics could not succeed, and the organizers felt obliged to make concessions, catering to their hedonism and setting up light and happy youth events such as the Olympic Youth Camp and the “Avenue of Games” (Spielstraße).

As with the difficult legacy of 1936, coping with the no less repressible present was far from straightforward. In key organizational phases, much remained unpredictable. “The youth of today is restless,” Daume proclaimed to the annual organizers’ assembly in 1969, “we find ourselves in an age of upheaval, sometimes of confusion and experimentation, an age without a binding framework. Our conception of the Games is not blessed with the equilibrium and calm it would have had in previous times. We don’t yet know how things will be in 1972.”13 At the point of delivery, too, much proved contradictory. As a somewhat downcast PR department noted in its assessment of secondary school pupils in March 1972: “Our experiences in schools are depressing. Like almost all spheres of youth, this one as well is dominated by a minority, which is always geared to be ‘against things.’ ”14 Even if such negative feelings could be attributed to the influence of a small minority, it is clear that much had changed since 1966, when 93 percent of sixteen to twenty-one year olds had voiced unequivocal support for the Games.15 At the same time, however, the PR team experienced little problem in enthusing teenage members of sports clubs and associations, and these became a natural and eagerly receptive group for ticket promotions. Many other young people who visited Munich were also swept away by the energy of the event. Werner Rabe, then a twenty-one-year-old reporter for the provincial Waldeckische Zeitung, now head of sport at Bayerischer Runkfunk, was overwhelmed by a feeling of his native country “at long last having arrived on the international stage,” noting simply: “Everyone had a bloody good time in Munich.”16 Not all German youths, therefore, felt the same way. And this is what made the organizers’ deliberations so difficult.

Coming one after the other, the European spring and summer of 1968 and the loss of lives at the Mexico Olympics later in the autumn gave the Munich organizers cause for concern. Even though four years remained before the Olympic flame was due to arrive in Bavaria, Daume wrote to Vogel in December, voicing his anxiety and suggesting “the discrete establishment of a ‘post for political planning’ or some such” within the OC in anticipation of political disturbances. According to “absolutely reliable information . . . received from student circles,” it seemed inevitable that the Games would attract the protesters’ wrath.17 In the event, no such post was created, but the passing of the watershed year in European history ushered in the OC’s earnest and at times tempestuous engagement with its legacies. In April 1969, the topic plunged the organizers into probably the most explosive of their twenty-seven regular board meetings between 1966 and 1973. The minutes record an “in-depth, lively discussion”18—an elegant shorthand for a blazing row, which resulted in four prominent chairs and members of subcommittees offering their resignation within days.19 The theme that caused such volatility was the relationship between art and politics and the practicalities of offering wider participation within the cultural program.

In one sense, these were not unfamiliar issues to the committee. Otl Aicher had addressed the notion of youth and its changing demands when he presented his initial thoughts as early as 1967, and the modern, light and democratic designs that he produced for the Games harmonized with the mood of the era.20 To a large extent, it was possible to bring the ceremonial aspects of the Games into line with contemporary expectations too. In 1969, Daume had worried if it was at all possible “to carry out Olympic celebrations, which essentially elevate [the event] into the ceremonial mode, in nineteenth-century dress. The youth of the world no longer has any understanding for the sort of celebration that revolves around gun salutes, ‘the parading of flags,’ military marching and pseudo-sacred elements.”21 But as already shown, the OC eventually wrung concessions from the IOC and, to a certain degree, realigned the centerpiece opening. Yet Kurt Edelhagen’s pastel-shaded, light Jazz orchestra hardly represented youth culture, and, as Daume realized himself, the country’s “intellectual heritage” could not simply be “hung from hooks on the tent roof.”22

Much would depend on the relationship between sport and its cultural setting. Munich’s bid had appealed to Brundage and the IOC by stressing the city’s importance as a center for high classical culture (opera, theater, classical music), but had been broadened to include modernism and the avant-garde as well. More importantly still, popular culture was assigned a central role, the organizers desperate to avoid the impression their program amounted to little more than the “sum of European tailcoat festivals,” as the Spiegel, unfairly, remarked at the end of 1971.23 Quite the opposite was the case. While high culture was traditional at an event like the Olympics, embedded in the mental matrix of key organizers, and unavoidable in a city of Munich’s stature, it was kept in the concert halls, theaters, and museums of the city center, at arm’s length from the sports arenas. To achieve its promised synthesis of sport and culture, the OC privileged less elitist forms of art and brought these as close to the Olympic venues as possible. As Daume emphasized, in contrast to the gigantic, year-long program in Mexico City that had merely juxtaposed sport and the arts, Munich sought to produce a “harmonious accord of the two.”24

The popular attraction at the Games, the Spielstraße (“Avenue of Games”), was placed in the Olympic Park itself. Initially brimming with optimism, however, the project became increasingly embroiled in controversy. The potentially explosive nature of the venture was immediately apparent when its prototype, “The Big Game” (Das Große Spiel), was unveiled by the chair of the arts committee, Herbert Hohenemser, in a “Report on the Extra-sporting Functions of the Oberwiesenfeld” at the ill-tempered board meeting. The ambitious and—in terms of Olympic history—radical plan to allow an interactive, largely spontaneous array of performance arts to unfold within the Olympic precincts sought both to “bring about the desired integration of sport and the arts” and “to make conscious use of the now almost ubiquitous movement of youth, i.e., to involve young people actively in this part of the Olympic idea and to include them in the preparation of it.”25 Positioning this vital encounter between “youth, sport and culture” at the heart of the Olympic event, the paper aimed to find “ ‘a common language’ . . . to reach a mutual understanding with the young” and create “a ‘vent’ for the youth movement and its unrest.” In the early part of 1969, however, this seemed a high-risk strategy—even the authors could not “provide a guarantee that everything would go off without incident”—and the OC reacted with caution. While Beitz and the representatives from Kiel (Geib and Bantzer) opposed it on practical grounds, others—Bavaria (Köppler) and Munich (Vogel and Abreß) to the fore—attacked what they saw as an overt politicization of art. In short, it was considered inappropriate for the OC to provoke controversy or try to “solve problems by giving people the opportunity to ‘act out’ the symptoms of those problems.” Hohenemser was furious, castigating his fellow OC members for fundamentally “misunderstanding the function of art in contemporary society” and doing little to engage with the “currents of the age.” With Daume straddling both camps, the committee agreed to the plan in principle but expressed serious reservations about the details.

Given the OC’s basic commitment and the president’s essential approval, the project would go ahead, albeit revised and reduced in scale. Over the next three years, the committee’s refusal to risk full engagement with youth culture condemned the “Großes Spiel” to a tug-of-war that pulled ineluctably toward what Hohenemser deemed the anathema of “the middle way.” At the end of 1969, responsibility for the “Spielstraße” (as it became known in its second phase) was handed to Werner Ruhnau, an architect who had not only collaborated successfully with Frei Otto on the German pavilion at Expo ‘67 but, as an expert on modernist theater design and mobile theaters, seemed ideally suited to the task.26 Ruhnau, however, was to be kept in check. The board reminded him at his first appearance that “improvised street theater, made up of external groups” was now off the agenda and that the whole program “should be coordinated centrally”;27 encouraged him at the next appearance to include more folkloric elements;28 and obliged him by contract to obtain the written permission of the general secretariat before signing acts and accept the possibility they might be cancelled at any given moment.29 In the end, he enjoyed much less room for maneuvering than he might have hoped for. Over “years of difficult negotiations”30 the venture became shorter and less radical from one meeting to the next, ever more well behaved and conventional and, in the eyes of some critics, even something of a “museum piece” (museal).31

The Spielstraße suffered because in addition to opposition from hypercautious or fundamentally unsympathetic political representatives, it attracted the disapproval of wider constituencies too. While it was supported by younger and more progressive members of the OC, it was obstructed by older sports functionaries, who had an important voice on many committees. General Secretary Herbert Kunze (b. 1908) and Max Danz (1909), the president of the West German athletics federation and a vice president of the NOC, attempted to sabotage it. Although it amounted to less than 2 percent of the Games’ total budget, Danz considered it a waste of money, worrying not only that its raucous activities might disrupt the sports events but also that its ethos clashed with a traditional understanding of art and culture.32 Typically for the old guard, art could assume a variety of roles and features, from the sublime to the decorative to entertainment, but it had nothing to do with sport or politics. These opinions were shared by colleagues such as Liselott Diem, who lambasted the Spielstraße in an article for the Sportinformationsdienst. In this influential information service for sports editors across the country, she cited the composer Carl Orff whose positive impressions of the modernist architecture and luscious green landscape contrasted sharply with his disdain for the avant-garde and popular culture on display around the park. Quoting Orff verbatim, Diem luxuriated in the opportunity to hail the Spielstraße an “insult to the Olympics.”33

But the Spielstraße proved equally unpopular in quarters where it might have expected a modicum of solidarity. While Ruhnau later maintained his project had received “collegial support” from Behnisch and Grzimek, documentary sources tell a different story.34 Bound contractually to conform to B+P’s overall scheme, Ruhnau found himself on the receiving end of the company’s exacting protection of its aesthetic vision.35 Behnisch, in fact, censored Ruhnau’s ideas the moment he sensed the merest threat to his own plans. In a memo of July 1969, he pledged to protect the Olympic Park from becoming a “repository for all different sorts of art and culture.” As opposed to this grab bag of art, the brownfield site he and his collaborators were in the process of reshaping would transform the Oberwiesenfeld in its entirety into a “work of art three hundred hectares in size.”36 When it became clear that the Spielstraße could not be dispensed with, Behnisch proceeded to limit the damage. As with Belling’s “Hiroshima sculpture,” he ensured it would have no lasting impact on his masterpiece, with the exception of a small classical open-air theater (the Theatron), which in any case had formed part of his original plans.

In its final incarnation, the Spielstraße was located along stretches of the northern and southern banks of the artificial lake adjacent to the Olympic swimming hall and divided into five major areas: the Theatron, a peninsula with performing areas and art studios, a large show terrace on the slopes of the Olympic mountain, a media street with several performing platforms, and a multivision center. Artists including actors, musicians, dancers, and pantomime and circus acts performed on thirty stages spread along half a mile of pathways. In this ultimate version, the Spielstraße sought to remove the division between athletes and visitors to the park, wooing spectators to abandon their passive spectatorship, immerse themselves in play, and in so doing, eliminate or reconfigure the roles consumers normally assumed when they entered a stadium.37

This conceptual frame was informed by the theater architect’s belief in the political nature of art and culture. While art had traditionally served as a tool for the powerful, he argued, at the very moment the division between artists and spectators is overcome, the latter are transformed into “citizens capable of acting with reason (der Mitbürger, der mündig wird).”38 Giving voice to their opinion, they break free from the constraints and diktat of political power. As explained in an interview given for this book, Ruhnau’s political philosophy and praxis were based on a literal reading of German etymology, the term mündiger Bürger (“responsible citizen”) deriving from Mund (mouth/voice).39 By addressing contemporary demands for greater participation, therefore, Ruhnau saw the Spielstraße as a necessary and positive response to the ideas of 1968. In this, he could count crucially on Daume’s backing. The president’s benevolence stemmed less from political persuasion per se, however, than the deep-seated desire to widen participation and democratize access to sport (see chapter 1). Vitally, too, both men shared a great admiration for the Dutch historian and cultural philosopher Johan Huizinga, whose seminal Homo ludens (1938) shaped Ruhnau’s philosophy of the Games and, with the exception of Karl Jaspers, tripped off the president’s tongue more readily than the work of any other thinker. As with Aicher, Huizinga formed a bridge of sorts between the head of the OC and the creative talent gathered around him. For Huizinga, Daume, and Ruhnau, play made “life worthy of living,” the ludique, “like music and painting, poetry and philosophy,”40 forming “one of the main bases of civilization.”41

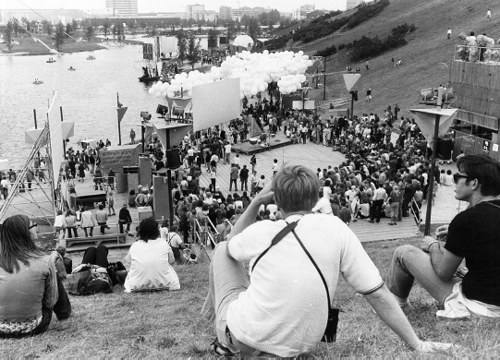

FIGURE 14. Locals in Bavarian costume watching events from the top of the Olympic mountain (photo: Oswald Baumeister, courtesy of Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo)

This fortunate, if not altogether unslippery compatibility of viewpoints flourished in the Spielstraße’s thematic focus on sport and the Olympics. On the one hand, the project attempted, in Daume’s words, to offset the “deadly seriousness” of Olympic ambition and thereby contribute to the serene and relaxed atmosphere of the Games, which the organizers had set as their ultimate goal.42 On the other, as he also noted, this counteraction could also explicitly criticize the demands and ethos of high-performance competition. For someone who normally extolled the value of top-level sport and justified the personal and financial sacrifices required to make it a success, the line he drew between mitigation and outright criticism could be dangerously blurred.43 It was characteristic of Daume, however, to hold contradictory ideas in close proximity and nurture them productively for his own ends. His mediatory position certainly allowed the Spielstraße to retain an edge, although it also required him to issue certain warnings. Sport per se could be criticized, but individual athletes, whom he viewed as “intelligent partners” rather than “musclemen,” were to be spared ad hominem malice. International guests of the Federal Republic, not least the IOC, were to be treated politely too, and all comments on East–West German relations strictly avoided.44 A proposal by former East German Klaus Göhling to erect a “humane Wall” of inflatable PVC cushions as a “contribution to détente,” having already been written to Erich Honecker, therefore, never progressed.45

FIGURE 15. Section of the Spielstraße (“Avenue of Games”) by the Olympic lake with provisional stage (photo: Marlies Schnetzer, courtesy of Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo)

For the main part, the Spielstraße laid on theater for all ages, from clowns and acrobats to pantomime and street performances. One popular example, which doubtless fitted Daume’s agenda of satirizing high-performance sport without overtly politicizing it, was an Olympic hamster treadmill, in which the artist Timm Ulrich ran a marathon each day without making any progress.46 But the venture, which comprised some two hundred artists and a further two hundred technicians and support staff from all over the world, afforded space to a variety of different art forms. Their activities ranged from multivision and multimedia art (photography, film, and video projections, and live-transmission from radio stations), to a sport photography exhibit, “free” jazz, and folk music, singer-songwriter composition, avant-garde painting and sculpture, “physical games” on which the public could play, inflatable air cushions, and installations for visitors to test their senses (e.g., Wilfried Mattes’ Haptic Way and Smell Events and Goehl, Pichler and Price’s Metallophony). Flower-arranging artists from Japan worked in harmony with the landscape to create idylls of calm among the hurly-burly.47 And Klaus Göhling—despite not hearing back from Honecker—was hired for alternative projects such as his Babbel-Plast and Schwabbelbrücke, an inflatable bridge that spanned the Olympic lake.48

Although never repeated at subsequent Games, the Spielstraße proved a great success. In just ten days it attracted an estimated 1.2 million visitors49—almost twice the total attending the other cultural events50—leading Daume to hail it as “one of the highlights of the Games.”51 Documentary footage shows the majority of visitors fully enjoying themselves. Given the scarcity of tickets for the sports venues, the public welcomed the fact that the Oberwiesenfeld had more to offer than just sporting competitions, and complaints were few and far between.52 Even when a male actor’s trousers slipped and exposed his genitals while playing a female weightlifter in the Grand Magic Circus, the prompt arrival of security personnel had more to do with the zealously prudish OC than public outrage.53 On the whole, the Spielstraße provided good-humored and easily consumable entertainment, which, despite the committee’s worries, catered admirably for the relaxed mood of the times, a soft cultural offshoot of 1968.

Even if the Spielstraße was museal when compared with its original intentions, it was not museal enough for some. Despite the systematic cutbacks and censorship to which it had been exposed, it managed to retain some of its desired political potency. This was delivered primarily by a small group of international street-theater troupes: the City Street Theater Caravan from New York, ETEBA from Buenos Aires, Jérôme Savary’s aforementioned Grand Magic Circus from Paris, the Marionetteatern from Stockholm, Mario Ricci’s Roman Gruppo Sperimentazione Teatrale, the Tenjo Sajiki troupe from Tokyo, and the Mixed Media Company from Berlin. Aiming to overcome the fundamental opposition between actor and spectator, each ensemble worked in its own peculiar style, exploiting free theater forms and dealing flexibly with the space available to them by moving constantly between different physical locations on the avenue. The radical edge to these “main-act” groups, however, derived primarily from their subject matter. Commissioned by the organizers to address the theme of Olympic history, each had been invited to represent the Games of a specific year: 408 BC, Athens 1896, Stockholm 1912, Los Angeles 1932, Mexico City 1968 and the future Games of the year 2000. This ambitious and provocative idea had originated from a basic scenario put forward by Berlin actor and avant-garde theater maker Frank Burckner, who had been involved with the planning of drama on the Spielstraße since the beginning of 1970. While Burckner set down broad guidelines, individual troupes could interpret the Games assigned to them as freely as they wished. By representing five previous Olympics as well as one from the future, Burckner’s aim, simply, was to contrast de Coubertin’s idealistic renewal of the classical tradition with negative aspects of twentieth-century history. “To act out the history of the Olympic Games,” he observed, “is to represent the educational idea of sport (Bildungsidee des Sports) as refracted by reality.” For Burckner that reality was dominated by “the constant threat to world peace by political, economic, religious and racial antagonisms.”54

In their underlying message, however, the plays used the Olympics as more than a convenient backdrop for the portrayal of world events. As further elaborations to Burckner’s basic scenario show, they criticized the Olympic movement itself and the perilous instrumentalization of sport by the political sphere. Thus the Athens and Stockholm Games of 1896 and 1912 came to stand for the imperialism, colonialism, and monarchical rule that marked their age. Backed by actors singing the “Internationale,” the last Games before the First World War, for instance, would juxtapose the German Kaiser’s imperialism with the communist pacifism of Karl Liebknecht. The 1968 Games, likewise, would reflect the force of Cold War tensions, the conflict between the “first” and “third” worlds, and the antagonism between contemporary youth and the older generation. Only the still distant Games of the year 2000, represented allegorically by Burckner’s own Mixed Media Company working from an outline by Austrian futurologist Robert Jungk, offered any glimmer of hope. In 1972, the year 2000 represented a tipping point, when humankind would either cast aside the “three-headed monster of capitalism, militarism and politics” that overshadowed past and future Olympics or face “global catastrophe” (Weltkatastrophe).55

When it came to the host nation, Burckner planned to confront its difficult past head-on. His original scenario envisaged Ricci’s experimental theater group working on Berlin 1936 rather than Los Angeles 1932. The mise-en-scène was to include an Adolf Hitler puppet that grew and shrunk depending on communicative contexts. The stage directions called for the repeated uttering of Nazi phrases such as “A youngster must be tough as leather, fast as a greyhound, and hard as Krupp steel,” and the action was to unfold before scenes from Riefenstahl’s Olympia and audio triggers such as the noise from “competitions and frantic roaring, interrupted by recordings of Hitler’s inflammatory speeches and victory announcements.” The spectators were to be treated, further, to Beethoven’s Ode to Joy interspersed with the sound of machine-gun salvos and bomber attacks.56 However, these suggestions were too radical even for Ruhnau, who did his best to persuade Burckner and the theater troupes not to “speak in favor of a specific ideology” or “counter-act the open and tolerant spirit of the ‘Spielstraße.’ ”57 But decisively, Daume objected himself, arguing that reminding the world of 1936 was hardly the best way to represent the new, modern Germany.58 Ricci duly obliged and presented an anti-capitalist play about Akron, Ohio, in the Depression instead.59 Despite Ruhnau’s claims to the contrary and Ricci’s nonchalance at the time, it is clear that the 1936 sketch was censored. The excuse given to the artists—that the OC could not risk the GDR leaving the Games in protest—had a hollow ring, and the fact that Burckner was allowed to approve proposals from that point on without prior consultation with the OC, smacks of a deal.60

Sensitivities over 1936, therefore, paradoxically opened the way for others to exercise less critical restraint. One notable beneficiary was Japanese writer, filmmaker, and dramatist Shuji Terayama, who failed to submit his outline in time and had to develop one after his troupe, Tenjo Sajiki, arrived in Munich. While Terayama had been tasked with representing the Mexico Games of 1968, the end product bore little resemblance to the events of any Olympics hitherto. Although drawing on the Tlatelolco Massacre, his uncanny premonition of events about to happen in Munich’s Olympic village remains chilling. Terayama’s play provided stunning images of human brutality and violence, and could hardly have contributed to a mood of “serenity” among the audience. Spectators regularly left the performances in shock at the terrifying scenes of black-hooded actors blindfolding, whipping, and manhandling other members of the troupe onto a platform among the spectators in the middle tiers of the Theatron.61 The victims—male and female—were stripped to the waist and hung over the guard rails by their elbows before dropping one by one, tortured and fatigued, into the audience from a height of several feet. Although ending with a large aluminum bird that flapped its wings but failed to fly—supposedly an expression of the hope that evil might one day be overcome—the play clearly emphasized merciless violence and the reign of terror.

The determination of most of the theater groups to make political statements galvanized the conservatives on the OC in their efforts to end the project. Here they had Black September to thank, whose actions in the Olympic village immediately brought about what years of agitation and the unfortunate actor’s dropped pants had failed to achieve.62 While every other aspect of the Games—sporting and cultural—resumed with the exception of a few official receptions on the afternoon following the attack, the Spielstraße shut for good on 6 September.63 The move to close it came from Ludwig Huber, the conservative Bavarian minister of finance, during an extraordinary meeting of the executive board, and not surprisingly it met with no resistance from his fellow OC members. At the same time, by contrast, the OC voted unanimously to leave festive decoration around the city in place.64 Daume was absent but did nothing to help the project survive. Protests by the artists, some of whom faced considerable financial difficulties, were to no avail. While Ruhnau, Burckner and representatives of the various troupes gave a press conference protesting their powerlessness and insisting their presence was now needed more than ever, the actors of Tenjo Sajiki expressed their displeasure by theatrical means. Three days after their last performance, they burned their props on stage before a full house at the Theatron.65

The story of the Spielstraße is one that began with a basic compatibility, although not identity, of viewpoints between the world of sports and the mood of the age, proceeded toward a watering down of radical intent, and ended within the safe confines of the “soft” popular reaction to 1968. This basic process of accommodation, assimilation, and then resistance repeated itself, significantly, along several key interfaces between the Olympic organizers and the younger clientele so necessary to their project. In the years leading up to 1972, the Munich Games attracted criticism from all corners. In May 1970, for instance, the Catholic Countryside Youth of Bavaria (Katholische Landjugend Bayerns) passed a resolution condemning the unfortunate “gigantism,” which despite the organizers’ best intentions had come to characterize the public perception of the Games. Expenditure on the 1972 event, it was claimed, had literally gone through the roof, leaving a lamentable lack of funds for youth in the countryside.66 More characteristically, however, less conservative quarters sustained the attack. As with many other institutions in the Federal Republic after 1968, high-performance sport came under fire from the neo-Marxist left that had informed the youth revolt. Critical theory determined the ways in which intellectuals framed radical thinking about sport and, by obvious extension, formulated a stinging critique of the Olympic Games.67 The “rediscovery” of an alternative Marx to the disgraced variant of Stalinist communism and the renewed popularity of Frankfurt school thinkers such as Adorno, Horkheimer, and Marcuse turned Marxism into “the secular religion of [the] epoch.”68 In the long run-up to the 1972 Olympics, therefore, the organizers would find the materiality of their enterprise examined by a critical apparatus shot through with a disdain for the body and natural antipathy toward sport.

By the early 1970s, a relatively coherent philosophy of sport had established itself around a number of radical thinkers such as Bero Rigauer (Sport und Arbeit, 1969) and Ulrike Prokop (Soziologie der Olympischen Spiele, 1972). Focusing on the repressive nature of sport and its relation to Freud and Marcuse’s dichotomy of labor and leisure, their arguments—as John Hoberman suggests—clustered around several main points.69 Sport, in their portrayal, no longer functioned as an alternative to work but, in its high-performance variant, mirrored and replicated it. It was dominated by the performance principle and set targets and quotas, in the East even producing an island of “capitalism within socialism,” and it served as an instrument of social control, depoliticizing by diverting attention away from the solution of social conflicts while simultaneously inculcating bourgeois values such as the primacy of the individual. Further, the asceticism and masochism demanded by training made sport a self-alienating activity, and the public’s infatuation with its heroes, in East and West, came dangerously close to the adoration witnessed in dictatorships. Thus, for Rigauer, Prokop, and the rest, in a political and economic order characterized by “commodified relations” and “domination,” sport “affirmed” the system, deflected natural impulses (triebablenkend), defused tensions, and generally depoliticized the masses.70 As the Munich Olympics came into view, other arguments evolved as well. At a special conference Olympic Games—Pro and Contra, held in November 1970 at the Academy of the Protestant Church at Tutzing—an event closely monitored by Vogel’s personal assistant Camillo Noel—Rigauer and other left-wing critics argued that the Games encouraged the implacable and increasing pressure to achieve (Leistungsdruck), while, worse still, creating the illusion of a harmonious and intact world.71 For the radical theorists, the Olympics merely reinforced the “fetish character” of sport and “inculcate[d] technocratic behavior” in spectators and competitors alike.72

Criticism of the Games also emerged from the aptly named “Anti-Olympic Committee” (AOC), whose founders Dieter Bott, Güther Amendt, and Gerd Dommermuth had been active members of the extra-parliamentary opposition. Although less sweeping in their condemnation of capitalist society, their antiauthoritarian critique drew from a familiar reservoir of neo-Marxist and psychoanalytic arguments. In distinction to Prokop and Rigauer, however, the three conceded that sport might have its positive sides too, admitting, under certain conditions, it could generate happiness and well-being. In fact, the AOC never resolved this tension between sport’s contribution to hedonistic lifestyles on the one hand and its dampening of the desire for revolution on the other. In contrast to the serious New Left theoreticians, however, the AOC typically expressed its viewpoints in jovial fashion. Despite the presence of left-wing luminaries such as Fritz Teufel, a former member of the Berlin Kommune I and well-known bogey of the bourgeoisie (Bürgerschreck), the formation of its Munich section early in 1970 had a touch of slapstick about it. In the techno-modern chic of the revolving restaurant at the top of the Olympic Tower, thirty activists declared the chapter open, before the manager called the police whose arrival was clearly visible from the 182-meter-high vantage-point, allowing the rowdy radicals to make their escape with comic timing. The AOC’s plans for the Games themselves were no less farcical, consisting of a scheme to hold a “Layabout” or “Hippie Olympics” (Gammler-Olympiade) with new disciplines such as sandcastle building, a one-hundred-meters-in-two-minutes race, and competitions in distance spitting and head wagging.73 Intended as a light-hearted provocation to attract the media to their antiperformance philosophy, the combination of left-inspired satirical protest and the Olympics proved highly successful. For reasons discussed in chapter 8, the Games enjoyed less than wholehearted public support after 1970, and newspaper journalists were only too happy to report on the AOC and its high jinks.74 Certainly they captured and doubtless contributed to the mood of the popular mainstream: one installment of Barbara Noack’s popular afternoon television series Der Bastian (1972) showed the eponymous hero—an attractive, apolitical “eternal student” with long blond hair—wandering the Olympic Park inventing the new discipline of “running backward” (Sieger im Rückwärtslauf).

To a certain extent, therefore, the AOC’s publicity schemes, popular television, and the public’s favorite elements of the Spielstraße began to merge. They did so generally because of the common slide of radical critique into less pronounced modes of behavior and expression as it passed into the popular realm. But they did so also because of the broad-based humanist philosophy of sport that originated from Daume and underpinned some of the OC’s more adventurous initiatives. As already noted, Daume hardly shared Brundage’s blind and all-encompassing belief in the positive virtues of sport. For the pragmatic West German, high-performance sport was no longer an “alternative” (Gegenbild) to industrial society but its “mirror image” (Ebenbild); it was hardly free of political abuse; and it most definitely found itself at the heart of the labor-leisure dialectic. To some degree, therefore, the OC president’s views resonated with those of the New Left theoreticians. But Daume was no Marxist and, treating such topics in a cultured but decidedly unideological manner, nearly always came to conclusions that were diametrically opposed to theirs. If sport in general was now the “brother of work,” the pure Huizingian effort (zweckfrei) required to play it remained essentially different from the “functional” variant (zweckgebunden) demanded by work; if competitive sport was a mirror-image of society, it should be modernized rather than abolished; and if international sport had been preyed upon by politicians, then it was the opportunists—such as Charles de Gaulle, whom Daume never tired of criticizing for his nationalistic remarks after France’s poor showing at the 1960 Olympics75—and not the athletes who should be taken to task. Moreover, wherever sport led to division, the social, religious, or political barriers imposed upon it needed to be lifted. Whether demanding equal access to elitist sports (such as tennis, sailing, golf, or horse riding) for all members of West German society, arguing for the democratization of sport as a fundamental human right, or facilitating the participation of “third-world” athletes at the Olympics, Daume—as one of his most famous speeches was aptly titled—believed in “Sport for All.”76

“Sport for All,” not surprisingly, became the working title of an interdisciplinary scientific congress “Sport in the Modern World—Chances and Problems” held for over two thousand scholars from seventy-five countries (including the GDR) at Munich’s Deutsches Museum on the eve of the Games. With panels on “Sports for the disabled,” “Sport in middle and old age,” “The theory and research of play,” “The contribution of sports in the integration of world society,” “The contribution of sport to social and economic development” and “Sport in Judaism/Islam/Hinduism,” the organizers operated with a broad understanding of their subject in the hope of attracting a large gathering of international experts to set the future agenda of the discipline.77 At the same time, the congress also sought to provide a forum to respond to the experience of “1968.” As educationalist Andreas Flitner, a member of the conference organizing committee, put it, the event was intended to counter youth’s suspicion that “the original meaning of the Olympic Games had been superseded by falsifying tendencies such as the self-representation of the host country, the national ambitions of teams and spectators, professional sportsmanship, the division of sport into artistic performances on the one hand and passive spectatorship on the other, [and] the commercial exploitation of the public.”78

In addressing these topics, however, the organizers followed a familiar pattern, playing it safe and failing to invite the New Left critics. The inevitable Liselott Diem aside, the congress was attended mainly by younger liberal and reformist academics from the West German social sciences and humanities, ranging from philosophers such as Dieter Henrich to educationalists Ommo Grupe and Hart-mut von Hentig. The performance principle was defended against the polemics of the absent New Left, most prominently by the liberal Karlsruhe sports philosopher, Hans Lenk. An Olympic gold medalist in the German rowing eight from Rome 1960, Lenk formulated his guidelines for a nonideological and undogmatic philosophy of sport around the voluntary nature of athletes’ participation in training and competition. Stressing the libidinous character of sporting endeavor, Lenk turned the New Left’s weaponry upon itself, comparing the athlete with the free-thinking, unalienated man of Marxist anthropology.79

Lenk was not entirely eulogistic, of course. Picking up the key political terms among moderate reformers of the era, he and others pleaded for greater participation and democratization in sport. As a result, the official report stressed that “many a critical word was heard” and the conference had “not become the cheering background for the Olympic Games.”80 Not everyone agreed, however. The West German delegation of university students, which had been invited on Daume’s suggestion along with four hundred international sports students, was particularly scathing in its criticism.81 In the words of the German University Sports Association (Allgemeiner deutscher Hochschulsportverband, ADH), which had selected participants and organized university visits for foreign students before the Games, the congress became a “stomping ground of apologists, who theologized and philosophized”82—an indictment indeed, given the moderate nature of their views compared to the New Left critics and the antiauthoritarian AOC.83 It was less the content of the conference that upset the ADH so much as its tone. Having gone to great lengths to prepare workshop presentations, the delegation felt their efforts were not taken seriously by the organizers and found themselves being treated in an authoritarian, pre-1968 manner. Conference materials were not supplied in time, suggestions about making more time available for real discussion were ignored, and, finally, a protest motion was rejected. In the end, the West German students abandoned any hope of influencing proceedings and resigned to follow the example of many of their foreign counterparts. After the opening, most visiting students found better things to do in Munich and simply stopped attending.84

Strolling around the city’s precincts they would have encountered a huge number of people their own age. Although precise numbers are impossible to establish, it seemed the youth of the world had indeed come for the Games. Many were housed in official and unofficial youth camps, which sometimes boasted the critical spirit of 1968 but more often than not provided a base to enjoy the hedonistic lifestyles the year had engendered. In total, the city and its surrounding towns and villages provided cheap accommodation for thirty thousand young visitors. The West German Sports Youth (Deutsche Sportjugend, DSJ) ran a camp that was larger than the Olympic village; twelve thousand youths were accommodated in Munich schools, which had closed early that year for the summer vacation; the Protestant and Catholic churches organized an ecumenical camp and opened all their community halls to provide a further 1,800 beds per night; and three thousand found lodging at a site organized by the federal minister of the interior in the Hasenbergl, not far from the Olympic Park in the north of Munich.85 To prevent the Olympic venues and the city’s other parks being transformed into spontaneous camping grounds, the city council also offered free emergency accommodation, the police willing to bus up to three thousand visitors to Ludwigsfeld in the northwestern outskirts.86

The most significant gathering of this type, however, was the official Olympic camp. Organized by the OC in Kapuzinerhölzl, less than a mile from the Oberwiesenfeld, it housed over 1,500 carefully selected seventeen to twenty year olds from fifty-three countries along with two hundred young leaders in temporary prefabricated houses.87 Stockholm had inaugurated the official youth camp in 1912 and it became a regular feature within the Olympic program from the Berlin Games onward. As an extension to the Olympic village for athletes (from 1932), successive organizers had seen it as an opportunity to foster the “understanding between nations” that played such a central role in de Coubertin’s philosophy. At Munich, this goal was achieved by inviting youths from around the world to live together for up to a month and providing them with opportunities to attend the Games and cultural events at the camp and around the region. In Munich, Kapuzinerhölzl fulfilled an additional role. Inspired by Daume’s vision, the OC came to view it as another way to compensate for the deficits of high-performance sport in the modern world. By bringing their own offerings of song, dance, and folklore, Daume noted at its opening ceremony, international delegations would establish an atmosphere of playfulness to counterbalance modern sport, which was “becoming ever more serious, sometimes even deadly serious.”88

Camp regulations were very liberal and discipline lax. Although some committee members had proposed rigid rules, progressive voices won the day.89 Although lights were supposed to be switched off at 11 P.M., participants effectively came and went as they pleased, many using Kapuzinerhölzl, at the bargain rate of twenty deutschmarks for board and lodging, as an inexpensive place to stay.90 As far as the camp’s program was concerned, the organizers decided to steer a safe course, avoiding controversial topics almost entirely.91 For most participants casual sociability counted more than political discussion. The Russian delegation always had the samovar ready for visitors from the West in their impromptu “Café Katjuscha,” and their first-class folklore performances led to invitations to participate in traditional summer fairs in local towns and villages.92 Extramural events run at no addition cost also proved very popular. There was, naturally, great uptake for the Games themselves, but half- and full-day excursions to the highlights of the Bavarian tourist circuit also attracted healthy numbers. Local firms and businesses went out of their way to offer tours, some drawing more interest than others. Munich’s breweries proved more attractive than the car manufacturer BMW or the waste incineration plant at Munich-South but—more telling about the low political appetite in the camp—drew almost three times the number of participants (1,315) than a trip to the memorial ceremony at Dachau on the eve of the Games (500).93 Indeed, even the controversial decision to continue the Games after the terrorist attack seemed to have little effect on the camp, numbers only dropping significantly at the end of the fortnight.94

Some members of the West German delegation—selected by the ADH (students) and the Deutsche Sportjugend (teenagers)—were disappointed by the other guests’ reluctance to engage in serious political activity. When they proposed a roundtable discussion to mark the “Day of International Solidarity with the Struggling People of Vietnam,” for instance, the Russians suggested holding a cross-country run in their honor instead. To the Germans’ chagrin, this softer proposal counteracted their own, and the day passed unmarked: “not even the Russians,” the moderate Frankfurter Rundschau commented laconically, “wanted to discuss Vietnam.”95 Soon the disgruntled youth of the host nation lashed out at the organizers. Foreign youths, they argued condescendingly, had been given too much opportunity to enjoy themselves, the organizers having turned them into passive consumers of sport and cultural tourism and “deluded them into believing in a sugar-coated world.”96 Personnel were accused of manipulating events within the camp too. As “an expression of disdain for the political contrasts and conflicts between East and West, North and South,” their emphasis on folkloric contributions had allowed the camp to degenerate into a “cultural Olympic Games” (Kul-turolympiade),97 and they had prohibited the distribution of flyers advertising demonstrations of one kind or another within the camp’s perimeters.98

Undeterred by the lack of political activism displayed by the foreign delegates, some student members of the West German group took matters into their own hands. Two days after the beginning of the Games, they successfully sabotaged a live television show featuring an array of prominent guests, including Max Schmeling, Jesse Owens, and Emil Zatopek. Invited by ZDF to symbolize the youthfulness of the Games and their contribution to international understanding at its evening gala Under the Tent Roof, they mocked what they saw as the superficiality of the broadcasters’ message by booing, chanting, whistling, and throwing paper airplanes at the cameras. Live interviews became impossible and the show was almost pulled.99 Back in the camp, they began publishing an unofficial bilingual newspaper, Olympix, with the declared aim of unmasking Olympic hypocrisy. Criticism of the Games’ commercialization featured regularly in the paper,100 as did the fact the camp’s housing had been provided by Munich arms manufacturer Krauss-Maffei.101 Not surprisingly, the IOC came under heaviest attack for its decision to continue with the Games after the massacre of the Israeli athletes.102

The dissatisfaction of the West German participants and the politically relaxed atmosphere of the camp that so antagonized them offer an insight into the mood of the youth and organizers of 1972. Despite the unruly behavior, the West German cohort at Kapuzinerhölzl was hardly a hotbed of left-wing radicals. But sensitized by the critical spirit of 1968, they were no longer willing unquestioningly to accept anything offered them by Daume and Vogel’s generations. At the same time, the camp turned out to be the least controversial of the OC’s youth-orientated undertakings, the organizers’ determination to promote a light and happy youth event at which serious politics were to be banished to the margins proving, in fact, a clear success. The camp leader reported “very good relations between all delegations” and received a postbag full of appreciative letters.103 As one member of the British student delegation put it: “For most people here this has been the experience of a lifetime.”104 In this sense the organizers were right to claim the success of their enterprise: just as in the more difficult circumstances of 1936 (as argued by Christiane Eisenberg), the Olympic Youth Camp in Munich went some way toward creating mutual understanding among young people from around the world.105 Setting aside its obvious winning formula—which provided young people, many from less prosperous nations, with inexpensive accommodation, cultural attractions, the buzz of Olympic competition, and the opportunity for liberal personal interaction in a safe environment—the Olympic ideal, for all its tarnished image, also triumphed on this occasion. As Kapuzinerhölzl 1972 showed, in the aftermath of 1968 the youth of the world did not always want to protest, they also wanted to have fun.

As well as arranging events specifically for young people, the organizers had to prevent their spontaneous activities from getting out of control or even off the ground in the first place. With mass youth participation at the heart of the Olympic ideal, the likelihood of large numbers of young people descending on the city gave the local authorities pause for thought. While no specific threat of major disruption emerged as 1972 approached (despite Daume’s doomsday fears at the end of 1968), the OC operated on the premise that they should nonetheless prepare for every eventuality, the loss of life in Munich and Mexico in 1968 doubtless looming in their minds. Indeed, events show they were right to have readied themselves: during the Games hardly a day passed when some K-group or other did not organize a political demonstration, attracting anywhere from a small handful of diehards to several thousand. Events also show that the OC’s cautious and meticulous planning paid off: with one major exception, Munich’s streets and parks remained largely peaceful throughout the Games. The forces of law and order might have been criticized after the Palestinian attack for lapses in security and ignorance of counter-terrorist technique. But it would be historically inaccurate to mock the imputed naivety of the German police, patrolling the Olympic sites—as narrator Michael Douglas commented in the documentary One Day in September—in pastel shades, “armed only with walkie-talkies.” Like the awful simplicity of September 11, the terrorist attack lay far beyond the conceptual horizon of the time (see chapter 7). But for those dangers and threats that lay within it, Munich was more than ready.

Responsibility for policing the Games fell largely to Manfred Schreiber, who became the OC’s special commissioner for security in 1970.106 Schreiber was an obvious choice, having served as president of the Munich force since November 1963. Born in the same year as Vogel (1926) and returning fifty-percent wardisabled after two years on the front, Schreiber’s arrival on the OC added a further powerful voice from the 1945ers driven to rebuild a functioning democracy on German soil. The first chairman of the student body (ASTA) at Munich University after the war, his career also followed a similar trajectory to Vogel’s—a degree in law leading to public administration in Bavaria’s Ministry of the Interior, a major position in the city of Munich, and then (after twenty years serving SPD and CSU mayors) promotion to federal level as a high-ranking civil servant in the Ministry of the Interior during Helmut Kohl’s chancellorship. Although an outsider on taking up office with the police, he rapidly adopted the force’s esprit de corps and never publicly criticized his subordinates, even when they bore the brunt of public abuse after the disastrous outcome to the hostage crisis in 1972.107

Schreiber, like Vogel, approached reform with a distinctive mix of political progressiveness and steely pragmatism. As a right-wing member of the SPD in the early 1960s, he was aware of the police’s traditionally reactionary stance. Indeed from the late 1960s onward, he became increasingly conservative himself, forcefully insisting on the state’s monopoly of violence and largely rejecting the critical analysis of society emerging in 1968.108 This creeping conservatism certainly informed some of his judgments on the Games, but his most decisive contribution owed more to policing reforms introduced in the early phase of his leadership in Munich. His predecessor Anton Heigl’s tenure had been marred by the controversial Schwabing Riots (Schwabinger Krawalle) of June 1962, when a minor infringement by street musicians at an open-air concert in Munich’s bohemian quarter escalated into violent clashes between (predominantly) young protesters and the city’s Schutzpolizei. Serious civil disturbances ensued and continued intermittently for five nights. As a result, Schreiber drafted a much-needed change of policy, formulating a flexible concept to help large deployments of police officers deal with confrontation at massed events such as demonstrations, rock concerts, and major sporting occasions. Tested successfully for the first time at the Beatles’ Munich concerts in June 1966, the “Münchner Linie,” as it became known, entered the vanguard of West German policing in the 1960s.109 Its distinctive emphasis lay on prevention and psychology. Overwhelming forces bearing the traditional armory of law and order were replaced, whenever possible, by smaller numbers using cognitive tactics. During demonstrations, channels of communication were kept open between organizers and participants, provocation was avoided, and physical force employed only when psychological means had been exhausted. While it would be wrong to see the “Munich Line” as a soft approach to public order offences, it often proved effective in stemming violent outbreaks before they gathered momentum. The “Easter riots” of 1968 were its one major failure.110

Schreiber’s imprimatur on the 1972 Games was evident even before his appointment to the OC. After consulting his police president, Vogel addressed the committee on security at the end of 1969, noting two potential threats that would demand subtle methods of engagement: “militant, anarchic activists” attracted by the “extraordinary publicity” of the Olympics and—an oblique and ultimately unfounded reference to the GDR—countries seeking to prove their national superiority outside the sporting arena. In any such case, Vogel argued, “every time the organ of the state reacted forcefully, it would provide welcome proof that the Federal Republic was not in fact a peaceable country, its society based on aggression and repression” and thus put the “success of the entire Games at risk.”111

In response to Vogel’s worst-case scenarios, the OC considered a twofold solution. They determined, first, to implore the IOC to share responsibility for maintaining the serenity of the Games—an idea ridiculed as completely unrealistic by Daume but pushed through by Genscher—and develop, second, their own domestic plan of action. Without being identified as such, the rudiments of the plan were pure “Münchner Linie”: “trying to redirect disturbances” and keeping “the forces of law and order away for as long as possible.”112 With the IOC predictably unimpressed by the suggestion it should guarantee civil obedience within a sovereign state, Schreiber, when appointed, pressed ahead determinedly. Early prevention and the avoidance of escalation were to become familiar topics at OC meetings over the next two years. Prevention was enshrined most prominently in the “Gesetz zum Schutz des Olympischen Friedens” (Law for the Protection of the Olympic Peace),113 legislation that suspended the freedom of assembly, as codified in article 8 of the federal constitution, within a five-hundred-meter radius of the Oberwiesenfeld and other Olympic venues for the duration of the Games and, on specific days, along the routes of the torch relay, marathon, and cycle races. After initial hesitation at federal level followed by altercations over technicalities between Bonn and the Bavarian state government, Genscher managed to see the proposal through cabinet, with the Bundestag approving it in spring 1972.114 The temporary law was supplemented by Munich City Council, which passed a further ban on political assemblies and demonstrations in the city center’s pedestrian zone on 16 August 1972. On the whole, the legal prohibition—an aesthetically and politically more attractive alternative to the ring of thousands of soldiers thrown around the Olympic sites in Mexico City—achieved its intended “general preventative effect.”115

Occasionally, however, it provoked rather than deterred. An event organized by the German Communist Youth Association (Kommunistischer Jugendverband Deutschlands) and their counterparts from another Maoist K-group (the KPD/ML) ended in violence, when marchers tried to force their way into the pedestrian zone. After the majority of demonstrators had dispersed, a core armed with motorcycle helmets, truncheons, and blackjacks attacked barriers manned by police at the Karlstor, resulting in (some severe) injury to fifty-eight officers.116 Mostly though, the Bannmeile, as it was legally known, represented more of a light-hearted challenge. Following an anti-Vietnam War rally, for instance, in which two thousand demonstrators from all over Germany participated after the opening ceremony, some members of the Munich KPD decided to take the protest further into the heart of the city. Simply hopping one S-Bahn stop from Karlstor to the Marienplatz, they embarked on a brief illegal protest of their own. After unfurling banners decrying U.S. involvement in Vietnam and attracting the attention of locals and tourists, they made off quickly before the police could intervene. The scale of this peccadillo and the fact that the “Storming of the Karlstor” was never repeated will have amply justified Schreiber’s methods, and the prohibition was loosened only for protests after the terrorist attack.

More controversially, however, the police president allowed the growing conservatism that marked his attitudes from the late 1960s to bear on aspects of the cultural program—the ill-starred Spielstraße becoming the main focus of his prevention-first mentality. By the eve of the Games, he was convinced that light entertainment in the Olympic park would be “hijacked by the public,” and remained adamant the police would be forced to shut it down at the first sign of trouble.117 Such anxieties and threats—which proved greatly exaggerated—formed the logical conclusion to long-running skirmishes over Ruhnau’s plans. Concerns about visitors’ safety, ostensibly, caused Schreiber to forbid the selling of beer on the Spielstraße, deny artists access to the majority of paths and roads in the Olympic park, and prevent the Olympic mountain from being transformed in the evenings into a “Mountain of Kinetic Pleasure” (Berg des kinetischen Vergnügens) with huge mobiles, a labyrinth, and light show. On his orders, this potential mecca of youth and alternative culture had to close at 10 P.M.118 Moreover, he contributed significantly to the downsizing of the artistic enterprise as a whole. Of the forty-eight original acts, twenty were rejected on aesthetic or financial grounds, while ten fell foul of the police president’s veto. Düsseldorf painter Günther Uecker, for instance, was prohibited from creating spontaneous works of art by letting the public fire differently colored arrows into wooden canvases—an act no more dangerous than the traditional shooting galleries at the Oktoberfest. More incomprehensibly, Schreiber cancelled a surreal wardrobe in which members of the Westfalian Landestheater were to perambulate across the Spielstraße discussing events of the day.119 Despite approval from noise-pollution experts,120 street musicians were forbidden from using amplifiers on the first three days of the Games, a ban that would be lifted, paradoxically, if they did not attract large crowds.121 Given Schreiber’s sanctions, it is hardly surprising that the Spielstraße organizers dedicated no more than 4 percent (DM 100,000) of their budget to pop music.122

Pop music—perhaps the common language of an emerging global youth culture—had concerned Schreiber for some time. By 1972, open-air festivals were a regular feature in West Germany, and Munich had established itself as the country’s hippie capital, the scene gathering regularly in the English Garden in Schwabing just a few kilometers from the Olympic venues.123 Although audiences often “got high,” rock concerts were not always unruly or illegal affairs: during the Games (30 August), for instance, the famously strident British band The Who performed their rock opera Tommy in front of an audience of two thousand at the Deutsches Museum, with the police reporting “no disturbances and no indications of drug consumption.”124 The idea of organizing a massed open-air concert as part of the cultural program of the Games, however, struck fear into the hearts of the authorities, who immediately pictured thousands of young Gammler (as hippies were known in Germany) and Hascher (marijuana smokers) milling around the city.125 Moral issues aside, the mere presence of drug users in the Olympic precincts would have obliged the police by law to intervene and created the scenario Schreiber was determined to avoid.

Schreiber’s insistence on avoiding awkward situations rang the death-knell on an event that might have written Munich into the annals of rock history. Inspired by Daniel Spiegel, who enjoyed close links with the British pop industry and was responsible for music on the Spielstraße, the art and culture department of the OC considered staging a massive music festival. Featuring many of the biggest names of the day—Led Zeppelin, the Rolling Stones, Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention—the “Rock Olympics,” as one London promoter put it, might easily have surpassed the Games themselves.126 In September 1971, Melody Maker and New Musical Express began announcing that the Olympic park was to host the largest series of rock and pop concerts ever held, a two-week mega-event to put Woodstock and other festivals in the shade. Spiegel’s vision depicted tens of thousands of music fans sitting on the slopes of the Olympic mountain, listening to music coming from the Theatron amphitheater through amplifiers and loudspeakers.127

When Schreiber discovered the plan—uncharacteristically late, in spring 1972—he was horrified at the prospect of an additional forty thousand to fifty thousand visitors swarming over the Oberwiesenfeld without tickets to the sports events. After meetings between Spiegel and his deputy Reinhard Rupprecht failed to resolve the situation, he used his powers of persuasion on the OC.128 Doubtless with images of Woodstock and the Rolling Stones’ 1965 and 1969 concerts in Berlin (Waldbühne) and London (Hyde Park) in mind, he argued that hoards of drug-consumers would refuse to leave the Olympic Park in the evenings, turn it into a camping ground, and impede the Games. Invoking a familiar topos of the time, he conjured up the “very unsightly image” of massed events and “the danger of epidemics.”129 Daume and the Bavarian ministry of the interior were of a similar mind, and Spiegel was instructed, with the help of “Johnny” Klein’s PR department, to ensure that his potential clientele stayed well away from Munich.130 When he attempted to salvage his project, suggesting that an alternative festival (Ausweich-festival) in the surrounding countryside might draw young people with little interest in sport away from the Oberwiesenfeld, he met with continued skepticism.131 The Bavarian Ministry of the Interior buried the project completely by instructing communes across the state to rebuff Spiegel’s approaches.132

The first tenet of the “Münchner Linie”—prevention at the earliest stage—was, therefore, fully activated for 1972.133 The second—stemming escalation with psychological rather than physical methods—was also much in evidence. Although apparently more liberal and relaxed, the latter formed a piece with the former. To ensure calm around the Olympic sites, Schreiber had them policed in innovative fashion. In the Olympic precincts, the normal forces of law and order were replaced for the duration of the Games by the Ordnungsdienst—comprising two thousand young police officers and federal border guards from all over West Germany who were active members of sports clubs and had volunteered to serve in Munich on paid leave of absence. Kitted out—indeed—in pastel shades, the Olys’s task was to keep the peace in a gentle and unobtrusive manner.134 As they were instructed in special training: “calming, relaxing and easing takes precedence over ‘ominous resoluteness.’ ”135 To this end, they benefited from the expertise of the Munich police’s in-house psychology department.136

Moreover, an internal police working group had assessed every potential threat. Based on scenarios that spanned from sabotage (e.g., soiling the water in the Olympic pool) to assassination, a range of flexible responses was envisioned.137 Among others, a so-called gag-commission developed a series of tactics to counteract the least serious disturbances. Political demonstrations in the Olympic stadium, for instance, would activate members of the Ordnungsdienst, who would march in wearing spiked helmets and carrying flashlights and hand sirens in an attempt to diffuse the situation through hilarity. If the humor of this scene and the well-scripted witticisms of the stadium announcer were not infectious enough, the security service would have opened fire on the demonstrators—with a specially constructed cannon shooting sweets instead of bullets.138