Activity 2

Category hierarchy

Overview

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a category as ‘a class or division of people or things regarded as having particular shared characteristics’. Marketers were early pioneers of grouping similarities within categories in order to establish targeted media campaigns to different classes of consumers. Later, the procurement community developed the concept to categorise potential supply-market opportunities and synergies in lieu – with Peter Kraljic being one of the pioneers. Each category and subcategory represented a separate sector within the supply market, thus offering a range of strategic offerings for category managers.

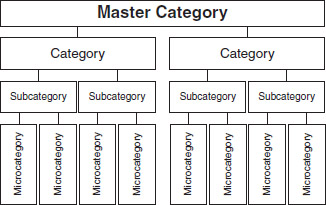

Category hierarchies illustrate how a supply market can be classified and broken down into a number of subgroups for strategic purposes. The classification of these clusters makes it easier for the category manager to understand how to leverage the value effectively from each constituent supply market.

Elements

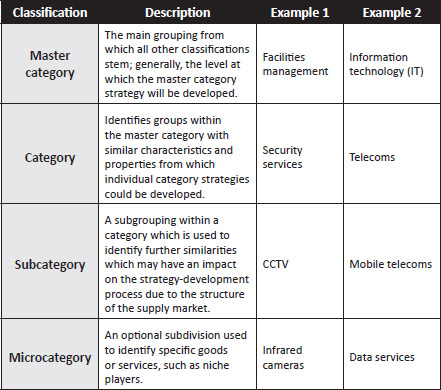

There are four main classifications of categories. Figure 1.5 outlines each of these, together with an accompanying description and two corresponding examples.

Jean-Philippe Massin (2012) has suggested that there are six factors that organisations should consider when creating categories (which he refers to as ‘sourcing groups’): (1) they should be based on a similar supply source, (2) they should possess similar production processes, (3) they should have a similar use or purpose, (4) they should have similar material content, (5) they should have similar specifications and (6) they should employ similar technology. If these six criteria cannot be satisfied, then the reality is that there is a separate category or subcategory that needs to be considered.

Category hierarchies are normally shown in a tree-diagram format, so that the breakdown of category division can be easily seen at a glance. It is recommended that a single ‘master’ hierarchy is developed for the organisation and that this activity is carried out centrally for the whole of the organisation.

So what?

A category hierarchy helps the team segment goods and services in relation to specific supply-market factors. This means that the resulting category strategy approach should be well placed to deliver the desired business requirements.

Segmenting the goods and services via a structured hierarchical approach will help the team identify possible volume opportunities for suppliers, capacity issues and ‘group deal’ potential. It should provide a ‘big picture’ of the overall category strategy for the market.

Having a robust category hierarchy gives the organisation a clear ‘road map’ for which categories to address. It acts as a scoping tool and helps prevent duplication between category teams. Effective hierarchies should provide category teams with strategic options to aggregate or disaggregate subcategories. Effective hierarchies should also help identify synergies between related categories and highlight the various interdependencies between expenditure.

Category management application

- Provides a classification system that helps structure categories in relation to the supply market

- Allows for categories/subcategories and associated responsibilities to be delegated to team members

- Allows for category/subcategory ‘waves’/’phases’ to be scheduled into the category management plan

- Assists with opportunity/leverage identification

Limitations

The categorisation process can become unwieldy, and so there needs to be clear boundaries around the scope of ‘what’s in’ and ‘what’s out’ of each category. There can also be a lot of crossover amongst products, and so care needs to be taken to avoid duplication of effort, resources and strategy during the category-planning phase.

One of the category manager’s biggest challenges is to get accurate and meaningful spend data to match each of the categories and subcategories. This is one of the current ‘blights’ of enterprise-wide spend data. Essentially the classification system that sits behind these systems (often referred to as a ‘material group coding’) needs to be rewritten around the category hierarchy in order for the spend data to provide the most value. If this is not aligned, then the category manager’s effectiveness is severely hampered despite the appeal of these ‘big data’ systems.

Ultimately, analysing categories in detail is seen as a useful part of the category management process, but the hierarchy approach can be viewed as ‘overkill’ in some instances, where, for example, the need to go down to the microlevel just isn’t viable or necessary. It should also be noted that some organisations prefer to develop individual category plans without first developing the category hierarchy, unfortunately seeing the latter as surplus to requirements.

Template

The following template can be used to identify category clusters:

- Template 2: Category hierarchy