Activity 18

Supply and value-chain analysis

Overview

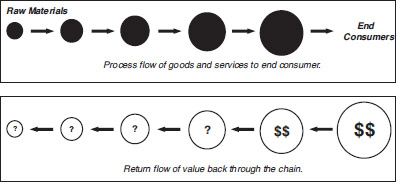

Supply and value-chain analysis is about the systematic breakdown and analysis of the primary supply chain at each tier so that opportunities to create value and mitigate risk can be identified. Arguably the theory supporting this can be traced back to Professor Michael Porter when he considered the competitive forces in a given market and then strung together the analyses of several markets in a supply chain to form the ‘value network’.

Supply and value-chain analysis builds on Porter’s concepts and incorporates supply-chain mapping, supply-chain analysis and value-chain analysis. It is essential that a clear distinction is made between primary and secondary (support) supply chains, with the focus remaining firmly on the primary (direct) supply chain.

Elements

There are five distinct stages required to develop a powerful and informative supply and value-chain analysis. These should be conducted sequentially, as follows:

- Supply-chain mapping – This is a systematic breakdown of the primary supply chain to identify each stage (tier), both upstream and downstream of the organisation. This should be conducted at the organisational level, rather than at the activity level, and must include all stages (including agencies and distribution channels) regardless of what part each plays in the chain. The aim is full transparency of every organisation in the primary supply chain.

- Cost analysis – This is a detailed, step-by-step breakdown of the costs of goods sold (COGS), working from the end consumer back to the origin of raw materials. Distinction needs to be made at each stage between selling price, profit, production costs, expenses and input costs for this analysis to be effective.

- Value analysis – This is a detailed analysis of the breakdown and allocation of profit throughout the supply chain, together with a contrast (by ratio or equivalent) to the costs. An analysis of the causes for the profit should accompany each stage.

- Risk and resilience analysis – This is a detailed analysis of the dependencies and vulnerabilities at each stage of the supply chain. This should be based on the likely impact on your own organisation in order for you to draw up a meaningful risk profile and to identify the overall supply-chain resilience.

- Opportunity analysis – This is, finally, a review of the costs, value and risks at each stage to identify opportunities for enhancing value and reducing risk.

So what?

Supply and value-chain analysis is incredibly powerful when done well. It gives you a detailed breakdown and analysis of the costs, value added and risks associated with a specific category at each stage in the supply chain. This provides a valuable basis for identifying potential opportunities to create value and mitigate risk exposure.

Typical outputs could include opportunities to consolidate markets, integrate production stages, streamline processes, outsource/insource, disintermediate, renegotiate and so on.

Category management application

- Maps every stage in the production and supply of a category, giving full transparency and providence for buyers

- Provides valuable detailed financial data to support future operational reviews and customer-supplier negotiations

- Profiles the risk and resilience within the primary supply chain

- Identifies potential areas for delivering breakthrough value

Limitations

The greatest challenge with supply and value-chain analysis is the time and resource requirement that accompanies this activity; it can be lengthy and time-consuming. The biggest issue here is that if organisations try to short-circuit these issues, then the analysis will be suboptimised. Of course, consultants love this kind of activity because it can help justify charging a large fee to their clients.

It is essential that the focus remains on the primary supply chain and does not get diverted into secondary (support) supply chains (i.e. indirect expenditure). However, this is easier said than done, as in practice these can be hard to separate.

The person or organisation undertaking supply and value-chain analysis needs a high level of competence and knowledge. It requires perseverance to break down the supply-chain tiers and then a forensic approach to the cost and value analysis. While many organisations claim to have transparency throughout their supply chains, the reality is often very different – as has been witnessed with a number of high-profile supply-chain disasters. Obviously, should blockchain technology become more widely adopted, actual transparency would be more easily achieved.

Another limitation comes from the degree of interpretation that accompanies the value analysis. The financial cost analysis is tangible and objective, but the accompanying value analysis becomes a matter of subjective interpretation as to why one supply-chain partner is more (or less) profitable than others. You could be tempted to turn to the academic work of Professor Andrew Cox et al. (2002) for supporting theory on core competence and critical asset analysis in supply chains, but this work is challenging in itself.

Template

The following template can be used to support supply and value-chain analysis:

- Template 18: Supply and value-chain analysis