Introduction

For the last two decades we have witnessed countless consulting practices and their client organisations promote the benefits of implementing category management. As a process it has been heralded as the procurement ‘panacea’ that delivers huge efficiency savings and business-wide benefits. It’s the one methodology that truly operates cross-functionally and works systematically through a strategic process to deliver exceptional outcomes.

Ironically, there is very little published material about category management – and what has been published remains shrouded in consultant-speak. As a result, organisations are left either to fend for themselves (and there are some really suboptimal examples of category management out there) or to employ expensive consultants to deliver fancy overengineered toolkits that never really get implemented.

This is what drove us to write this handbook: to offer a simple practitioners’ guide that lifts the lid on category management and increases the application of best practice in the procurement field. When done well, we have seen category management deliver exceptional results, and so we hope this practical handbook helps inspire you to take up category management and deliver great things for your organisation!

Background

The origins of category management track back to the proliferation of marketing and merchandising strategies in the 1980s. Back then, multibrand fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) manufacturers realised the benefits of grouping their products into ‘categories’ of associated offerings in order to maximise their market position and to drive synergies across various retail channels and consumer groups. This association of products and classification of customer groupings became known as category management and the natural flow through to supply-chain operations quickly followed on.

Since then, category management has expanded beyond FMCG and become intrinsically focused on buy-side supply markets. Through the 1990s, procurement consultancies picked up on the added value of category management and ‘process engineered’ the approach so that it could apply to indirect, as well as direct, spend. It quickly became associated with large strategic analysis and sourcing toolkits. As authors, we were introduced to category management a little over 20 years ago and have seen both the positive benefits and the downsides of processes like these.

When applied well, considerable business benefits were realised – far more than any typical procurement approach – and category management has grabbed considerable management attention. However, sometimes it didn’t go so well, and the only winners were the consultants who collected their overinflated pay cheques.

More recently however category management has matured and become grounded in everyday business practice, but it still remains a ‘black box’ and one of the preserves of the consultancies.

This is what this handbook is about. Category management is a well-established, proven methodology that delivers business benefits. However, it’s not rocket science and you don’t need expensive consultants to deliver the mystique for you.

What is category management?

Category management is a continuous process of gathering, analysing and reviewing market data in order to create and execute spend strategies that deliver long-term business benefits.

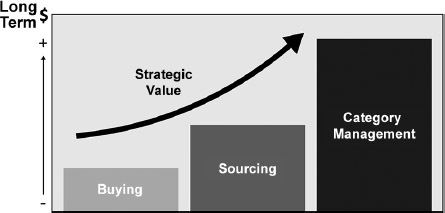

Let’s look at this definition closer by eliminating other activities that sometimes get confused with category management. First and most importantly, category management is different from sourcing. So many people get this muddled (including some of the so-called leading professional bodies), and this is a major inhibitor of the strategic creativity of potential solutions. While sourcing (if done well) can have many of the same activities, it is only a one-dimensional approach to category management. Category management can include sourcing but also considers a whole load of other potential solutions, including make versus buy, outsourcing, insourcing, offshoring/reshoring, renegotiation, forward/backward integration, supplier relationship management, new product development, acquisitions and joint ventures, to name but a few. As such, category management should deliver significantly more value than sourcing, which in turn delivers more value than buying, as illustrated in Figure I.1.

Similarly, category management is not a ‘project’. If you haven’t done it before, then obviously it has a clear beginning, but it shouldn’t have an end. To make life easier you might organise responsibilities into category management teams and have them run various delivery ‘projects’ against a time frame, but this is merely for convenience. True category management is iterative, constantly evolving and transitioning from one generation to another; the process is cyclical and by definition never ending.

Finally, category management is not a spend report (i.e. it does not accept organisational spending as is); it’s a strategy that delivers business benefits based on changing the way expenditure and resources are managed.

Key principles

There are six key cornerstones of successful category management:

- 1 Customer focus – Everything in category management must be customer led, with targets and objectives being focused on business-wide priorities (what we later refer to as ‘business requirements’). Where the customer is internal (e.g. areas of indirect spend), then this is about excellent stakeholder engagement and a service-oriented philosophy. Where the customer is external (e.g. areas of direct spend), then the business requirements will need to be a carefully considered trade-off between serving business needs and delighting customers. Business requirements form the underlying bedrock of all category management, and without a thorough analysis and understanding of these, any category management solution is most likely to be suboptimal. You will consider these in more detail in the research stage of our category management process (refer to Stage 2, Activity 8).

- 2 Changing the status quo – Everything in category management is about change (and improvement). Put simply, if you don’t want to change then don’t engage in category management! Perhaps more fundamentally, category management is about ‘breakthrough’ thinking – that is, seeking out and exploiting new opportunities to make fundamental leaps of improvement.

- 3 Process thinking – As already mentioned, category management is a cyclical process of sequential activities. By sequencing these activities into a step-by-step process, category management teams can be systematic in their approach to strategy development and implementation. Governance can also be created, giving the opportunity for business controls and peer review/challenge at appropriate places.

- 4 Cross-functional approach – Fundamental to successful category management is the business-wide approach. Here stakeholders are not merely ‘consultees’; they become actively engaged in leading and managing the category activities. It moves the category management process away from functional procurement and embeds it as a business process of change.

- 5 Facts and data driven – All analysis, strategies and decisions should be based on a strong foundation of facts and data. This helps to remove subjectivity, bias and organisational politics. When faced with well-informed market intelligence, the business is able to buy into strategies for change.

- 6 Continuous improvement – Unlike a project, category management does not have a defined end. The process of activities may conclude after one category strategy has been successfully implemented, but this is the trigger for the next generation (iteration) of category management to evolve. In other words, the process is cyclical, constantly seeking out better and better solutions to manage each spend category.

Process and governance

There are many different formats for the category management process, with no definitive guidance on which process is best. The authors have worked with clients that have three-stage category management processes, others that have 12-stage processes and many in between these extremes. There isn’t a right or wrong number of stages.

In this book we adopt a ‘classic’ five-stage category management process (see Figure I.2). We have done this for several reasons, but mostly for convenience. Primarily, five-stage processes seem to be the most popular across businesses. Having five distinct stages keeps the structure relatively simple and groups activities into a natural sequence; any less than this can make the process stages seem too large, while more than this seems to overcomplicate matters. We have grouped individual activities logically into this five-stage structure based on our practical experience of working within and facilitating category teams through a wide range of categories throughout the world.

In addition to a distinct number of process stages, there are specific ‘gateways’ that sit between each stage. These gateways provide excellent check steps or review points to monitor progression through the process. It is generally advisable to insert some form of governance around these gateways. More formal ‘mature’ category management processes treat these gateways as ‘go/no-go’ decision milestones, thus maintaining focus and a degree of project management behind each process iteration.

While we are fans of this relatively simple five-stage process, it is worth drawing a comparison with other published methodologies. For example, the United Kingdom’s Chartered Institute of Procurement & Supply (CIPS) recently created its own category management model based on a circular cycle of activities. This process has many similarities to the process we follow in this handbook, albeit that we have simplified our overall approach to make it more generic across multiple industry sectors.

Two of the key features of this CIPS category management model that differ from our approach include (1) the alignment of category strategy and execution around the key activities of a sourcing process, and (2) a specific emphasis on postaward supplier management and continuous improvement.

The confusion between sourcing and category management is a common occurrence throughout the industry. It is understandable that CIPS (and other procurement consultancies) base their category management models on sourcing – they do after all concentrate on selling procurement services – but this approach is far too limiting and denies the true strategic intention that sits behind category management. By mistakenly including sourcing and supplier management processes in a category management process, there is a major presumption that all spend strategies will require a sourcing solution. The reality is that these strategies might not require any sourcing whatsoever and so to automatically build a sourcing stage into the category management process could be extremely limiting on the variety of strategic options that the category management process creates.

The five-stage category management process that we detail in this book has a far broader business appeal than just procurement. It leaves ‘no stone unturned’ in its attempt to find strategic solutions for each category. While sourcing a new offering from the supply market could be one option, we strongly encourage you to think more broadly than this and pursue a variety of ideas and options in order to deliver sustained value to your business.

Presentation of this handbook

This handbook has been subdivided into five key sections, each representing one of the stages of our category management process. Within each section we explain the tools and techniques that you are likely to use. Each tool or technique is presented in graphical form with accompanying commentary, in the following format:

- Overview – A brief introduction of the tool/technique and an explanation of how it fits in the category management process.

- Elements – A description of the key components of the tool/technique and how they are applied.

- So what? – A practical guide as to how the tool/technique is generally used on an operational level and what it delivers for organisations.

- Category management application – Suggestions as to how the tool/technique can be applied specifically as part of an overall category management approach and the benefits that it will bring.

- Limitations – An open and even-handed critique of the tool/technique.

- Template – A reference to the corresponding template that accompanies each tool/technique for your easy application.