RENEWABLE ENERGY

CLEAN, AFFORDABLE, AND RELIABLE

Contrary to what many people think, renewable energy is not a source of energy we’ve just discovered. Humans have relied on renewable energy since the very first humanlike creatures roamed the planet over three million years ago. Throughout most of human history, the energy human beings needed to survive and prosper has come from food molecules — primarily seeds, berries, and roots. The energy in these foods provided the means by which we built early civilizations. Our early ancestors also burned wood to warm their caves and cook their food.

Plants, of course, are renewable resources, capable of regenerating themselves from seeds, roots, or tubers. But plants are here by the grace of three other renewable environmental resources: soil, water, and air.

Although our predecessors, and virtually all other life forms on the planet, received the energy they needed to survive from plant matter, the source of the energy extracted from our botanical companions is not the soil or water or even the air. The source is the sun — a massive hydrogen fusion reactor 93 million miles from planet Earth.

Plants capture the sun’s energy during photosynthesis. In this complex set of chemical reactions, plants synthesize a wide variety of food molecules from three basic “ingredients”: carbon dioxide from the air, water from the soil, and solar energy from the sun. Solar energy that drives photosynthetic reactions is captured and stored in the chemical bonds of organic food molecules. When food molecules are consumed by us, or any other animal for that matter, stored solar energy is released. Solar energy contained in food molecules and liberated by the cells of our bodies is, in turn, used to transport molecules across cell membranes and to manufacture protein and DNA to power our muscles and heat our bodies.

Humankind’s greatest achievements were made by using the sun’s energy. The Egyptians, for instance, hauled massive stones to build the towering pyramids with nothing but ingenuity and the muscle power of conscripted laborers fueled by organic food molecules courtesy of the sun and plants. The Romans expanded their holdings to build a vast and prosperous empire, too, all with horse and human muscle powered by plant matter and, ultimately, sunlight.

For most of human history, then, renewable energy reigned supreme.

Then came the fossil fuel era.

Lumbering to a start in the 1700s in Europe and the 1800s in North America, the fossil fuel era was first powered by coal, an organic sedimentary rock. Coal owes its origin to plants that grew in the Carboniferous era some 250 to 350 million years ago. Coal replaced waning supplies of wood in Europe and fed the industrial machinery that made mass production — and modern society — possible. So, in a way, the Industrial Revolution was also powered by solar energy — ancient sunlight that was captured by plants millions of years ago.

For many years, coal reigned supreme. But eventually coal was forced to share its kingdom with two additional fossil fuels: oil and natural gas. Also produced from once-living organisms (notably, aquatic algae), these fuels were relatively easy to transport and, like coal, are found in highly concentrated deposits. Over time, oil and natural gas, along with coal, became major components of the world’s energy economy.

In 2009 (the latest year for which data were available), oil supplied 37 percent of the United States’ total annual energy demand. Natural gas provided about 25 percent, and coal supplied 21 percent of our energy needs. Nuclear energy provided just under 9 percent. The remaining 8 percent of the United States’ energy diet was supplied by four renewable resources: hydropower, solar, wind, and geothermal. Canada is similarly heavily dependent on oil, natural gas, and coal. In 2008, oil, natural gas, and coal provided 66 percent of Canada’s energy. Nuclear energy provided about 7 percent, and hydropower provided 25 percent of the nation’s energy.

In the more developed countries, fossil fuels clearly dominate the energy scene today, but their glory days are coming to an end. Oil and natural gas are entering their sunset years, making the shift to clean, affordable, reliable, and abundant renewable energy inevitable. Fortunately, we have lots of options.

MAKING WISE CHOICES

To make the wisest choices as individuals — and as a society — we need to understand our predicament — what energy resources are endangered. Many energy experts believe that global oil production will peak or already has peaked. Peak oil could result in a devastating rise in prices. Global natural gas production may also peak soon, creating further turmoil. Clearly, we need replacements for these two fossil fuels. But what about coal?

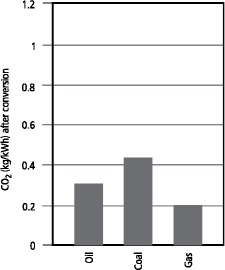

Given the devastating impact and high cost of global warming and a host of other energy-related environmental problems, coal will very likely need to be phased out in the near future. Although coal is abundant in North America, China, and elsewhere, and its use is bound to increase dramatically as oil and natural gas production peak, coal is the dirtiest of all fossil fuels. Coal combustion not only produces sulfur oxides and nitrogen oxides that react with water and sunlight to form sulfuric and nitric acids that poison rain and snow, coal combustion also generates millions of tons of particulates that cause asthma and other respiratory diseases. Coal combustion also yields millions of tons of ash containing an assortment of potentially toxic materials such as mercury. Much of this ash is disposed of in ordinary landfills alongside our trash, and the toxic chemicals in the ash can eventually seep into ground water. Perhaps most important to our future, however, is that coal combustion produces enormous quantities of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide — far more carbon dioxide per unit of energy produced than any other fossil fuel in use today (Figure 1-1).

Despite industry’s frequent mention of an elusive “clean coal technology,” it’s difficult to make coal clean. Without question, the efficiency of coal combustion can be increased to reduce the amount of pollution per unit of energy produced, and I applaud any efforts to do so. But capturing carbon dioxide and storing it underground — one way to make coal cleaner — is energy intensive and will dramatically increase coal combustion itself. (Carbon capture increases the energy consumption at a power plant by around 25 to 30 percent.) Even with the best technologies in place, coal combustion will produce lots of pollution; it is inevitable, and the more coal we consume, the greater the output of potentially harmful gases and particulates and solid waste. Carbon dioxide, for example, is the unavoidable byproduct of combustion of any carbon fuel. Much of the sulfur that contaminates coal in varying degrees can be removed before or after combustion by pollution control devices. The sulfur, however, does not magically disappear. Most of what is removed by smokestack scrubbers ends up in a toxic slurry that is disposed of in landfills where the toxic components can leach into groundwater. It’s a simple mass balance phenomenon: if the chemical ingredients of the pollutants are in the fuel, they’re going to be a byproduct one way or another. They won’t mysteriously vanish because a coal executive tells you they do. In the end, “clean coal” seems like nothing more than just a deceptive marketing ploy of the coal companies to make a dirty fuel appear more environmentally acceptable.

Fig. 1-1: Not all fossil fuels are created equal. Coal has a much higher ratio of carbon to hydrogen than oil, which has a much higher ratio of carbon to hydrogen than natural gas. The more carbon a fuel contains, the more carbon dioxide it produces per BTU of energy released.

To make the wisest choices, we also need to understand the end uses of each of the fuels we are trying to replace. Remember, it is the products and services these resources provide that we want, not the fuels themselves. As natural gas supplies decline, we don’t necessarily need more natural gas. We need to ensure the services that natural gas currently provides. For example, many homeowners use natural gas to provide space heat, to heat water for showers, dishwashing, and laundry, and to cook food. Finding replacements for natural gas means finding ways to provide these services via clean, renewable resources and technologies — for example, solar hot air systems to heat our homes and solar water systems to provide space heat and heat water for domestic use.

This book lays out the options available to us that can ensure the continuation of services currently supplied by now-failing or environmentally unacceptable fuel sources. Don’t forget, though, that the easiest way to meet our needs is often achieved by simply being more efficient. A warm home or business, for instance, can be achieved by sealing up those obnoxious cracks around windows, doors, and elsewhere. It can also be ensured by installing additional insulation to the ceilings and walls of our homes and offices. Additional space heat can be provided by retrofitting our homes for passive solar — adding windows on the south sides of our homes to let in the low-angled winter sun. Space heat can also be achieved by installing active solar hot water systems (Figure 1-2). Solar hot water systems generate hot water that can be integrated with heating systems already in many of our homes — from baseboard hot water systems to radiant-floor systems to forced-air systems. There are many other options out there. For example, homes can be heated via heat pumps, devices that remove heat from the ground or even the air and transfer it to the interior of a building.

To make wise choices, you also need to know which options make the most sense. How do we assess the appropriateness of a renewable energy option?

Two of the most important criteria are cost and net energy yield, which often go hand in hand. Consider an example:

To replace declining supplies of oil, many fossil fuel advocates suggest that we can turn to oil shale and tar sands. Unfortunately, a huge amount of energy is required to extract the oil from these natural resources. The energy required to extract oil from tar sands and oil shales subtracted from the energy of the final product is known as the net energy yield. It can be thought of as the energy returned on energy invested. Both oil shale and tar sand oil production have very low net energy yields compared to conventional oil (although new processes have steadily improved the net energy yield of tar sand production). The lower the net energy yield, the more costly the fuel. As the price of conventional oil increases, the cost of oil shale and tar sand oil will inevitably rise.

Environmental impact should also be a key criterion when selecting an alternative fuel. To build a sustainable future, we must develop fuels that meet our needs for energy without sacrificing an equally important, though often overlooked, requirement: our need for a clean, healthful environment.

Resource supplies are also vital. From the long-term perspective, it makes sense to pursue those resources that are most abundant. And what could be more abundant than a renewable fuel supply?

In sum, when seeking alternatives to waning supplies of fossil fuels, we must proceed with caution and intelligence. We need to develop energy resources that meet our needs and have the highest net energy yield, the most abundant supplies, and the lowest overall cost — socially, economically, and environmentally. In this book, I present up-to-date information on net energy yields to help you sort through the list of options. I’ll also look at the pros and cons of various technologies, to help you make the wisest choices.

Fig. 1-2: This solar hot water system on The Evergreen Institute’s classroom building provides hot water for showers, washing, etc. It could be expanded to provide space heat as well.

Before we go much further, though, let us take a brief look at energy itself. To help you understand this elusive entity, I’ll cover some basics here, then introduce more concepts later in the book as we explore the various renewable energy systems.

UNDERSTANDING ENERGY

Like love, energy is all around us, but is sometimes difficult to define.

Energy Comes in Many Forms

In our quest to define energy, let’s begin by making a simple observation: energy comes in many forms. For example, humans in many countries rely today on fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas to meet many of their energy needs. And some use nuclear energy derived from splitting atoms. In other countries, wood and other forms of biomass, like dried animal dung, are primary forms of energy. (Biomass includes a wide assortment of solid fuels, such as wood; and liquid fuels, such as ethanol derived from corn, and biodiesel made from vegetable oils; and gases such as methane, released from rotting garbage and animal waste.) And don’t forget sunlight, wind, hydropower, and the geothermal energy produced in the Earth’s interior. Even a cube of sugar contains energy. Touch a match to it, and it will burn — giving off heat and light, two additional forms of energy.

Energy Can Be Renewable or Nonrenewable

Energy in its various forms can be broadly classified as either renewable or nonrenewable. Renewable energy, as noted earlier, is any form of energy that’s regenerated by natural forces. Wind, for instance, is a renewable form of energy. It is available to us year after year thanks in large part to the unequal heating of the Earth’s surface. When one area is warmed by the sun, hot air is produced. This hot air rises and, as it does, cooler air moves in from neighboring areas. As the cool air moves in, it creates winds of varying intensities.

Renewable energy is everywhere and is replenished year after year. It could provide humankind with an enormous supply … if we’re smart enough to tap into it.

Nonrenewable energy, on the other hand, is finite. It cannot be regenerated in a timely fashion by natural processes. Coal, oil, natural gas, tar sands, oil shale, and nuclear energy are all nonrenewable forms of energy. Ironically, most of these sources of energy are the products of natural biological and geological processes — processes that continue even today, but at rates not even remotely close to our rates of consumption. Coal, for instance, still forms in swamplands, but its regeneration takes place at such a painfully slow rate that it is impossible for the Earth to replenish the massive supplies that we are consuming at breakneck speed. Because of this, coal, oil, natural gas and the like are finite.

When they’re gone, they’re gone.

Energy Can Be Converted from One Form to Another

There’s still more to this mysterious thing we call energy. Even the casual observer can tell you that energy can be converted from one form to another. Natural gas, for example, when burned, is converted to heat and light. Coal, oil, wood, biodiesel, and other fuels are also converted to other forms of energy during combustion. Heat and light are byproducts of these conversions. Heat, in turn, can be used to make electricity. But the possibilities don’t end here. Visible light contained in sunlight can be converted to heat. It can also be converted to electrical energy by solar cells. Even wind can be converted to electricity or mechanical energy that can drive a pump to draw water from the ground. Humans have invented numerous technologies to convert raw energy into useful forms.

Energy Conversions Allow Us to Put Energy to Good Use

Not only can energy be converted to other forms, it must be for us to derive benefit. Coal, by itself, is of little value to us. It’s a sedimentary rock that looks cool, but it is the heat and electricity produced when coal is burned in power plants that are of value to us. Sunlight is pretty, and it feeds the plants we eat, but in our homes and factories, the heat the sun produces and the electricity we can generate from it are of great value to us.

In sum, then, it is not raw forms of energy that we need. It is the byproducts of energy conversion — new types of energy that are unleashed when we convert raw energy through the many ingenious energy-liberating technologies — that meet the many and complex needs of society.

Energy Can Neither Be Created nor Destroyed

Another important fact about energy is something you may have learned in high school, that is, that energy can neither be created nor can it be destroyed. Physicists refer to this as the First Law of Thermodynamics or, simply, the First Law. The First Law says that all energy comes from pre-existing forms. Even though you may think you are creating energy when you burn a piece of firewood in a wood stove, all you are doing is unleashing energy contained in the wood — specifically, the energy locked in the chemical bonds in the molecules that make up wood. This energy, in turn, came from sunlight. And the sun’s energy came from the fusion of hydrogen atoms in the sun’s interior.

Energy is Degraded When it is Converted from One Form to Another

More important to us, however, is the Second Law of Thermodynamics. The Second Law says, quite simply, that when one form of energy is converted to another form — for example, when you burn natural gas to produce heat — it is degraded. Translated, that means energy conversions transform high-quality energy resources to low-quality energy. Natural gas, for instance, contains a huge amount of energy in a small volume; the energy is locked up in the chemical bonds that attach the carbon atom to the four hydrogen atoms of each methane molecule. When these bonds are broken, the stored chemical energy is released. Light and heat are the products. Both light and heat are less concentrated — and thus, lower quality — forms of energy. Hence, we say that natural gas, which is a concentrated form of energy, is “degraded” when burned. In electric power plants, only about 50 percent of the energy contained in natural gas is converted to electrical energy. The rest is “lost” as heat that dissipates into the environment.

No Energy Conversion is 100 Percent Efficient (Not Even Close)

This leads us to another important fact about energy: no energy conversion is 100 percent efficient. When coal is burned in an electric power plant, only about 30 percent of the energy contained in the coal is converted to useful energy — in this case, electricity. The rest is lost as heat and light. The same goes for renewable energy technologies. One hundred units of solar energy beaming down on a solar electric module won’t produce the equivalent of 100 units of electricity. You’ll only get around 8–20 percent conversion using the various solar modules on the market today. (However, some new technologies can capture and convert about 35 to 40 percent of the incoming energy. So, things are improving.)

Energy is lost in all conversions. As another example, most conventional incandescent lightbulbs convert only about five percent of the electrical energy that runs through them into light. The rest is released as heat. (Incandescent lightbulbs should really be called “heat bulbs.”)

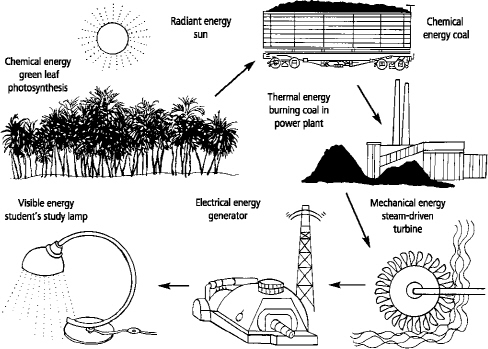

Each conversion in a chain of energy conversions loses useful energy, as shown in Figure 1-3. To get the most out of our primary energy sources, therefore, we have to reduce the number of conversions along the path.

You may be wondering if all of this discussion of energy losses is a violation of the First Law of Thermodynamics, which states that energy cannot be created or destroyed. The answer is no. The energy losses that take place during energy conversion are not really losses in the true sense of the word. Energy is not destroyed; it is released in various forms, some are useful to us and others, such as heat, are not so useful. Chemical energy in gasoline propels a car forward along the highway. Some is also lost as heat that radiates off the engine. This waste heat is of little value — except on cold winter days when it is used to warm the car’s interior. Eventually, however, all the heat produced by a motorized vehicle escapes into outer space. It is not destroyed, per se, but it is no longer available to us. Hence, the conversion results in a net loss of useful energy.

Fig. 1-3: Energy conversions occur commonly in the production-consumption cycle of various fuels. Unfortunately, none of these conversions is 100 percent efficient, so energy is lost at each stage. The key to using energy efficiently is to limit or eliminate conversions.

Energy, quite simply, is valuable because it allows us to perform work. It powers our bodies. It powers our homes. It powers our cars and trucks. We cannot exist without energy.

OK, so now you’re “cooking” with information about energy. You know there are many forms of energy. You know that energy can be renewable or nonrenewable. You understand that raw energy is not as important to us as are its useful byproducts such as electricity, light, or heat. You also know that energy can be neither created nor destroyed; it can only be converted from one form to another. Raw energy is useful to us because it can be converted into other forms. And you’re privy to the fact that no energy conversion is 100 percent efficient, not even close.

You also understand that during conversions, useful energy decreases. That fact, in turn, is important for nonrenewable fuels; once they’ve burned, or reacted, in the case of nuclear fuels, their energy is gone forever. The heat radiates endlessly into outer space, heating the universe, as it were. Renewable energy resources, on the other hand, can be regenerated year after year after year. If we’re going to persist as a society, it is renewable energy resources we’ll need to rely on. Unlike fossil fuel energy and nuclear energy, renewable resources can be regenerated continuously as long as the sun continues to shine, making our lives bright and cheery and comfortable.

With these important points in mind, let’s define energy.

Energy is the Ability to Do Work

To a physicist, energy is “the ability to do work.” Any time you lift an object, or slide an object across the floor, you are performing work. The same holds for our machines. Any time a machine lifts something or moves it from one place to another, it performs work.

According to physicists, work is also performed when the temperature of a substance is raised. Therefore, your stove or microwave is doing work when it boils water for hot tea or soup.

Work and Power

Physicists aren’t content to just define energy; they also like to measure it. Because the units of measurement they use come in handy when sizing renewable energy systems, it is worth learning a few of the most common ones.

Measuring Mechanical Energy

If you push a 100-pound box of potatoes 10 feet across a wooden floor, physicists would proclaim that you have performed work. And you’d probably agree. But how much work have you performed?

To calculate the amount of work performed, scientists use a very simple equation:

Work = Force x Distance

In this case,

work = 100 pounds x 10 feet

= 1,000 foot-pounds of work.

Although “foot-pounds” isn’t a particularly useful term, the example shows you what is meant when we say that energy allows us to do work.

It is also important to be able to measure the rate at which work is performed. Physicists define the rate at which you or a machine performs work as power. An adult, for instance, might be able to push a 100-pound box 10 feet across a floor in 4 seconds. It might take a 10-year-old 10 seconds to perform that same amount of work. Clearly, the adult is more powerful. Even though they perform the same amount of work, the adult performs it more quickly.

For the mathematically inclined: power is the force x the distance (or work performed) divided by the time it took to complete the task. Another way of writing this is:

Power = Work/Time.

In the case of the adult,

power = 1,000 foot-pounds/4 seconds,

or 250 foot-pounds per second.

In the case of the child,

power = 1,000 foot-pounds/10 seconds,

or 100 foot-pounds per second.

I bring this up not to torment you with physics, but because you will encounter units of work and power as you study renewable energy options. However, in this book, most of our attention will focus on thermal and electrical energy.

Thermal, or heat, energy can be measured in BTUs (British Thermal Units). One BTU is the amount of energy it takes to raise one pound of water one degree Fahrenheit. Remember, as just noted, raising temperature is a measure of work.

Furnaces, boilers, and water heaters are all rated by their BTU output. Solar water heaters are rated — and compared to one another — by the number of BTUs of heat they will generate under controlled conditions (so you can see how one stacks up against another). In addition, energy auditors, whom you may be hiring, typically calculate heat loss from buildings in BTUs — usually BTUs per square foot per year. Solar heating specialists calculate heating loads (how much heat a home needs) in BTUs as well. Cooling requires a calculation of how much heat in BTUs must be removed from a building per hour to maintain comfort.

A single BTU is not much energy when compared to what it takes to provide hot water for a family of four or to heat a home for a year. Most of the time, you will be dealing with tens of thousands of BTUs or, in the case of home heating, millions. A house, for example, can gain tens of millions of BTUs of heat energy from the sun each year.

While the BTU is a measurement of heat energy, electrical energy has its own set of terms that you’ll need to be familiar with if you decide to do something about your home’s electrical energy consumption. While I’ve got you on the torture rack, let’s take a look at them now. The pain will ease up shortly.

Electricity is really the flow of electrons, tiny subatomic particles, through wires. To help students understand electricity, most teachers liken electricity to water flowing in a hose; the water molecules are akin to the electrons flowing in a wire.

As you know, water can flow slowly or very quickly. How fast water flows is determined by a force: water pressure. Water flowing out of the hose of a rain barrel, for example, flows pretty slowly. Water flowing through a downspout from the gutter that drains a roof flows more quickly. It is under more pressure than the water flowing out of the rain barrel.

How fast electrons flow through a wire also depends on a force much like the water pressure in a hose. This force is measured in volts. Voltage is an electromotive force — a force that causes electrons to move.

In the world of electricity, electrical power can be calculated using the same equation we used to determine mechanical energy:

Power = Force x Distance/Time.

So, in electrical energy, the force is the volts. What about the distance and time components of the equation?

Electrons can flow at different rates in wires, too. The number of electrons flowing past a point in the wire at any one time is measured as amps, short for amperes.

Multiplying volts (force) times amps (distance/time), therefore, gives you a measure of power. Power is measured in a term familiar to most of us: watts. To simplify matters, physicists calculate watts using the following equation:

Watts = amps x volts

Watts is a common term that you need to become familiar with. Fortunately, most of us already are familiar with watts. When we shop for a new microwave, we shop by watts: This unit is a 1,000-watt microwave; that one is a 1,200-watt unit. The higher the wattage, the faster it will cook our food. We’ve all shopped for 100-watt lightbulbs or new compact fluorescent lightbulbs that produce the same as a 100-or 75-watt incandescent.

Watts is used as a measure of instantaneous power consumption of motors, electric hair dryers, and lightbulbs. Watts is also used to measure power production. A 4,000-watt solar electric system, for instance, produces 4,000 watts on a bright sunny day. A 10,000-watt wind turbine produces 10,000 watts when the wind is blowing at a certain speed (usually around 26 to 30 miles per hour). Since 1,000 is a kilo, a 1,000-watt solar electric system is a 1-kilowatt system or 1-kW system. A 10,000-watt wind turbine is a 10-kW wind turbine.

Although wattage is a measure of instantaneous power production, it’s not the instantaneous production of power that matters to us when sizing home energy systems, but power production over time — measured in watt-hours and kilowatt-hours. A 1-watt lightbulb shining for one hour consumes 1 watt-hour of energy. A 100-watt lightbulb burning for 10 hours consumes 1,000 watt-hours of energy, or 1 kilowatt-hour.

Utility companies bill our energy use measured in kilowatt-hours, and it is the kilowatt-hour production of solar and wind systems that are of greatest concern to those who are thinking about turning to solar or wind to meet their needs for electricity.

Ok, let’s stop here and turn our attention to the shining star of the energy show, renewable energy.

WHAT IS RENEWABLE ENERGY?

Renewable energy, as just noted, is a form of energy capable of being regenerated by natural processes at meaningful rates. Wood, for instance, is a form of renewable energy. It’s produced by trees from minerals in the soil, carbon dioxide in the air, water from the ground, and energy from the sun. Wind, flowing water, and sunlight are also renewable energy resources (Figure 1-4). Heat within the Earth’s crust can be considered to be renewable, too, as are the tides.

Fig. 1-4: The energy of falling water can be captured on a small scale or a very large scale. Although this form of energy is relatively clean, damming rivers can create enormous environmental impacts.

Most of these renewable forms of energy are made possible by the kingpin of all renewables, the sun, the center star of our solar system.

Let’s get something out of the way right from the start, however. The sun is really not a renewable energy source. This blisteringly hot ball of gases is a huge fusion reactor, near the center of our solar system, 93 million miles from planet Earth. Fusion reactions occur between hydrogen atoms in the sun’s interior. When two hydrogen atoms fuse, they form a helium atom and enormous amounts of heat, light, and other forms of energy. That’s what makes the sun tick.

And the Earth, too.

Although only about 0.5 billionths of the sun’s energy strikes the Earth, that is enough to power virtually all life on land and sea, and it has been responsible for the build-up of vast resources of fossil fuels that are now quickly (in geological and human time) sliding toward oblivion.

Technically, though, the sun is a finite resource. Someday its fuel source will run out. But don’t fret; there’s good news: the sun is going to burn brightly for at least five billion years or more before it dies out on us. And when it does, it will be all over. “We don’t have five billion years of sunshine, however. Scientists calculate that the sun’s energy output will slowly increase over the next billion years, and in about one billion years, the sun will be so hot that it will extinguish all life on planet Earth.”

Although the sun is a finite resource, teachers, energy experts, and books on the subject still refer to it as a renewable energy resource.

THE PROS AND CONS OF RENEWABLE ENERGY

Before examining the pros and cons of renewable energy, it is important — indeed vital — to point out a dangerous trap that many fall into, notably, lumping renewables into a single category. Renewable energy encompasses a half dozen or so fuels — solar, wind, hydropower, biomass, hydrogen, and geothermal — and a number of different technologies.

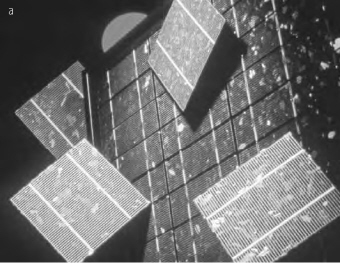

Because there are many renewable energy technologies, it is misleading to lump them into broad categories. It is inaccurate, for example, to speak of solar energy technologies as a single entity; granted, they are fueled by a common fuel source — the sun — but there are a number of very different technologies that derive their energy from the sun: solar electric cells, passive solar, solar hot water collectors, and solar hot air collectors. (See Figure 1-5.) And each of these technologies has different uses, benefits, challenges, and costs. Troubles often arise when critics of renewable energy lump all available technologies together. For example, opponents of solar energy are fond of saying that “solar energy is too expensive,” which is a little like saying, “All Americans are idiots,” just because there are a few nitwits amongst us.

Although it is true that some solar technologies like solar electricity are expensive (at least currently), others are quite cost-competitive with conventional technologies. A good example of the latter is passive solar heating. That said, there are times when the most expensive technologies like solar electricity or photovoltaics produce electricity at a lower cost than conventional sources. In less developed countries, for instance, it’s often cheaper to install solar electric modules in rural villages than to string power lines hundreds of miles from existing coal-fired power plants to service such remote locations.

Even in industrialized nations, the cost issue is not always straightforward. Solar electricity can be less expensive than conventional electrical power in some locations. For example, when powering highway warning signs, it is much cheaper to install a solar electric-powered sign than to run an electric wire to the unit (Figure 1-6). Emergency call boxes are similarly powered for the same reason (Figure 1-7). Moreover, if you build a home just two- or three-tenths of a mile from a power line, you’ll find that it is often less expensive to install a full-scale solar electric system than it would be to string electric wires from the utility’s power line to your home. In fact, running an electrical line a couple of tenths of a mile might cost $20,000 to $30,000. And that doesn’t give you a single kilowatt-hour of electricity. All it provides is access to the utility’s grid.

Financial incentives make solar electricity much more cost-competitive to homeowners. Given various local, state, and national incentives, at least in the United States, homeowners can install a pretty impressive solar electric system for $30,000. And if you build more than half a mile from an existing power line, a solar system is hands-down, without question, much less expensive than connecting to the electrical grid — unless your utility picks up the tab for running the wire to your home. Further clouding the cost issue, some states or utilities in states such as California, Wisconsin, Illinois, New York, New Jersey, Colorado, and Missouri offer generous incentives to homeowners and business owners that reduce the cost of solar electric systems. State, local, and federal incentives can reduce the initial cost for homeowners by up to 50 percent. Businesses may receive even greater benefits for solar electricity, reducing the cost of a system by about two thirds.

Photo: Astropower

Fig. 1-5: These solar cells (a) are made of silicon, which comes from silicon dioxide from sand and quartz. Solar cells convert solar energy into electricity. Many solar cells are wired together in a module which is mounted on the roof or on a free-standing rack or pole (b) like these arrays at the Solar Living Institute in California. The array on the right side of the photo is mounted on a tracker that points the array toward the sun from sunrise to sunset.

Fig. 1-6: This flashing stop sign in rural Missouri warns drivers of a very dangerous intersection. It is powered by solar electricity.

Fig. 1-7: Emergency phones along a remote northern California highway are made possible by solar electricity. Stringing electrical lines to such locations would be cost-prohibitive.

Solar electricity also makes sense in cases where grid power is expensive. In California, for instance, electricity from the grid during peak usage periods typically runs from 30 cents to over a dollar a kilowatt-hour, far more than the cost of generating electricity from sunlight. Grid power in Germany is currently 75 cents per kilowatt-hour, creating a bonanza for US solar cell manufacturers.

When listing the pros and cons of renewable energy technologies, then, we need to be very specific. Keep this in mind when discussing renewable energy technologies with friends, government officials, or opponents. Watch out for people who unfairly lump renewable energy technologies into one group.

With this friendly advice in mind, we can now look at some of renewable energy’s pros and cons.

The Benefits

Renewable energy offers many benefits, outlined here.

Renewable energy resources are available year after year — often in predictable amounts in all parts of the world. Thus, they’re fairly reliable resources — energy sources we can count on — and they’re renewable. They’re not finite like coal, oil, natural gas, and nuclear.

Another big advantage of renewable energy technologies is that, with few exceptions, the fuel is free. It’s not under the control of oil cartels or wealthy multinational corporations. Although it costs money to tap into these renewable energy resources, no one controls the price of most renewable fuels, so we won’t experience rising prices. Installing a renewable energy system, therefore, serves as a vital protection against rising fuel prices experienced as finite resources like oil and natural gas dwindle. Renewables will provide a hedge against inflation!

Renewable energy is clean and nonpolluting; except for the manufacture and installation of the technologies needed to capture these forms of energy, there’s very little, if any, pollution or environmental damage created by the use of most renewable energy technologies. Renewable energy technologies are the cleanest form of energy, next to energy conservation and energy efficiency measures.

For the most part, the technologies required to convert energy from renewable sources to useful energy are already available. No new breakthroughs are required for their widespread use, although improvements in technology and new developments in some areas could help lower their costs and make some sources more practical.

Many renewable energy technologies and fuels are cost-competitive with conventional technologies and fuels. Right now, large-scale wind power, passive solar heating, passive cooling, solar hot water, solar hot air, solar electric systems in rural settings or in regions with high electric costs are frequently cost-competitive alternatives to fossil fuels and nuclear energy.

Renewable energy technologies are, for the most part, decentralized sources of power, not vulnerable to sabotage. And, as just noted, they’re not controlled by multinational corporations. Much of the renewable energy business currently consists of smaller companies, with a few big dogs like General Electric and British Petroleum starting to play key roles.

Renewable energy technologies permit individuals to control their own power production. When you install a solar electric system or a wind generator, you become your own plant manager. You’re no longer at the mercy of your local power company. As a result, renewable energy helps us attain personal freedom and independence.

For those who love gadgets, renewables are fun. There’s hardly a day that goes by that I’m not reading the meters on my solar electric, solar hot water, or wind systems and making graphs to track how much energy I’m getting from each one.

The Disadvantages

As with all things in our lives, there are downsides to renewable energy, many of which we can easily work around or eliminate with a little ingenuity.

Renewable energy technologies and renewable energy fuels constitute only a small portion of our current energy production and consumption, so they have fewer advocates to promote their use, although that is starting to change through the efforts of progressive governors and legislators and big companies such as General Electric and Vestas.

Renewable energy is often actively lobbied against by the powerful fossil fuel industry, for example, coal companies or the nuclear industry. They and others often spread misinformation about renewable energy to make their case to the public. With such powerful forces working against renewable energy, creating a renewable energy future won’t be easy.

Compared to conventional fossil fuels, renewable energy research and development is poorly funded in most countries, the United States and Canada being prime examples. Here again, there are notable exceptions. In Europe, several countries such as Germany, Great Britain, and Holland are making tremendous efforts to tap into renewable energy. In recent years, the United States has taken a much more active role in promoting renewable energy as part of the nation’s clean energy policy, especially under the leadership of Barack Obama. Generous tax incentives and training programs have helped spur the industry.

Renewable energy resources such as wind and solar are not available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, unlike fossil fuels. Renewable energy technologies often require some means of storage so surpluses can be stockpiled for later use. Storing renewable energy can be difficult and costly. That said, solar and wind system owners meet this challenge by installing batteries that store surplus during times of excess and provide electricity when the sun or winds are not available. Serious efforts are underway to develop long-term, massive energy storage systems for large commercial systems.

Conventional fuels may help meet our needs when the sun or wind are not available. In the future, for example, the world’s renewable energy system will very likely consist of a combination of renewable technologies — such as wind, hydropower, and solar — with backup energy from nonrenewable technologies, such as natural gas and even new coal-fired power plants. Facilities like natural gas and new coal-fired power plants can be brought up online quickly, providing a steady supply of energy to meet our needs.

Regional energy transfer may also help ensure a continuous supply of energy. Deficiencies in one part of a country, for instance, can be offset by surpluses generated in others, as is common in the electric-generating industry today. Electricity generated by wind farms in Kansas, for example, could be fed to Colorado or New Mexico to meet their needs during cloudy or windless periods.

Even though many renewable energy technologies are not available 24 hours a day, seven days a week, the amount available in a given year is quite predictable. That is, you can count on a certain amount of sunlight and wind. Individuals can design systems that generate surplus during times of excess for use in times of shortage. Net metering policies in some states make this quite simple.

Another downside of renewable energy is that there are not enough experts and local suppliers of renewable energy technologies. Open the Yellow Pages and check listings on solar hot water installers and compare the number of these companies to the number of companies that install conventional water heaters. In the vast majority of the country, the latter list is much longer.

Some technologies are quite expensive and not yet competitive with conventional fuels at current prices, although this could change with rising oil and natural gas prices and financial incentives. That said, as mentioned earlier, many renewable energy technologies are quite affordable — even cheaper than conventional technologies.

Converting to renewable energy technologies may need to be done on a house-by-house basis, which will require the efforts of millions of informed homeowners.

With this list of pros and cons in mind, let’s begin our exploration of the various renewable energy technologies that are available to homeowners and business owners. Along the way, you’ll learn more about the pros and cons of each energy source/technology. I also hope to shatter a few myths that are holding back this important revolution in home and business energy production.

PROSPECTS FOR THE FUTURE

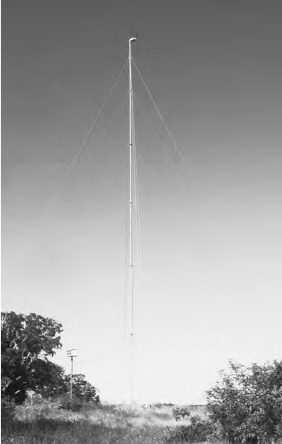

For 14 years I ran my entire Evergreen, Colorado house and office almost 100 percent off renewable energy — sunlight, wind, and firewood. I used only a small amount of natural gas for heating water and cooking meals. I currently run The Evergreen Institute’s Center for Renewable Energy and Green Building in Missouri entirely off solar and wind energy (Figure 1-8).

Fig. 1-8: On top of this 126-foot tilt-up tower, we fly a 2.5-kW wind turbine that provides a good portion of The Evergreen Institute’s electricity.

You can live independently, too.

As you will see throughout this book, energy independence is almost always more easily attained by those building anew than by those retrofitting a home for self-sufficiency. When building a new home, simply orienting it to the south to increase winter heat gain and reduce summer heat gain can cut one’s heating and cooling bills by 10 percent. By concentrating windows on the south side of the home, a homeowner can cut heating and cooling bills by up to 30 percent. But like many readers, you probably don’t have the luxury of starting from scratch. You have a home that’s firmly anchored to the ground and, most likely, not ideally situated for optimal solar gain. If you want to retrofit your home for greater energy self-sufficiency, you’ll face a much bigger challenge than the lucky person who builds anew.

Don’t be discouraged, however.

You can easily cut your energy demand by half, perhaps even more, with some simple, cost-effective measures that improve the energy efficiency of your home. A few more “aggressive” energy efficiency and conservation steps could allow you to slash your fuel bill even more.

With these measures in place, you can install some renewable energy technologies that will bring your household closer to full energy independence. In doing so, you’ll not only reduce your current monthly fuel bill, you’ll help protect yourself from the potentially devastating rise in fuel costs. You’ll also help reduce greenhouse warming and a host of other serious environmental problems, and you make it easier for the United States and Canada — and all other nations — to meet their energy needs in a sustainable manner. The more of us that take these steps, the better our nations’ futures. This stuff is vital to national security.

Fortunately, there are ample supplies of renewable energy in many areas. Many renewable energy technologies such as solar hot water and residential-scale solar electricity are easy to install in a business or residence. Others, like large-scale wind power, will require the deep pockets of private industry and the far-sighted assistance of local, state, and federal governments.

In our quest for a better, brighter energy future, we should never lose sight of two facts. First, there’s much we can do to improve energy efficiency in our homes. A huge amount. Moreover, we can improve energy efficiency without sacrificing services we’ve become accustomed to. We can live lightly and live well! Conservation isn’t “freezing in the dark,” as former President Ronald Reagan was fond of saying. Conservation is living comfortably at a fraction of the cost of our wasteful lifestyles. Conservation, if we’re smart, means a better life for us.

Second, renewable energy resources are vast. They outshine the remaining nonrenewable energy resources by so much, it makes your head spin. Enough sunlight strikes the Earth in 40 minutes to power all of our energy needs for a full year!

You may be surprised to learn that renewable energy, even sunlight, can be used to power nearly all of your family’s needs — even in some of the gloomiest parts of the United States. Renewable energy and conservation, then, are the key to a sustainable future, and you and millions of people like you can turn that key.

I encourage you to think outside the energy box, too. Look for avenues that lead to energy savings, for example, growing more of your own food. Home gardens can save huge amounts of energy, and can help create a more independent and sustainable lifestyle. But what if you don’t have room in your backyard, or don’t even have a backyard? You can be part of a community garden. Community gardens are often placed in vacant lots in cities and towns. They allow people to grow much of their own food. By growing your own food, you help reduce the need for the massive amounts of energy currently used to produce and ship food from farms all over the world to people like yourself.

Travel consumes huge amounts of energy, too, as does the production of clothing and other goods we buy. Buy locally. Consider vacationing locally. Consider used goods. Recycle everything you can. Buy recycled materials whenever possible. Thinking beyond heating, cooling, and lighting will help you place yourself on the path to energy independence and a cleaner, healthier, safer future. Renewable energy and conservation are the key to a sustainable future. You, and millions of people like you, hold that key.