WIND POWER

MEETING YOUR NEEDS FOR ELECTRICITY

In 2004, I took a group of students in my Introduction to Sustainable Development course at Colorado College to a coal-fired power plant in Denver. After trudging through the hot, noisy, and dangerous facility, listening to the spiel on the virtues of coal, we hopped in our vans and drove north to Wyoming to visit a wind farm. The wind farm was perched on a plateau visible from the interstate. As we drove onto the property, the giant white wind turbines came into full view.

Fig. 9-1: These contented bison graze around the base of the gigantic wind turbines at the Ponnequin Wind Farm in northern Colorado, demonstrating that wind energy can be coupled with other commercial activities, notably farming and ranching, providing dual incomes for landowners.

Bison grazed around the base of the towers, munching on grass (Figure 9-1). My students were awestruck when we got out of the vans and stood at the base of these massive, quiet turbines towering 260 feet above our heads.

As I looked around, I could see smiles on my students’ faces. The contrast between the noisy, dirty coal-fired power plant fed by huge piles of coal shipped in from hundreds of miles away, and the hushed efficiency of the wind farm fed by an abundant, clean, and free renewable resource was just too much for them. “Wow,” one student said. “This is amazing!” burst another.

I was pretty amazed, too. It was my first up-close encounter with gargantuan commercial wind generators. Watching the shadows of the turning blades was indescribable — “way cool,” as one of my young students remarked. I don’t know how I could improve on his assessment. What is more, the turbines were remarkably quiet. All they made was a swooshing sound as the blades turned in the cold wind.

This chapter is not about large commercial wind systems; it is about smaller systems, typically referred to as small wind systems. These are systems that generate electricity for individual homes, businesses, farms, and ranches. This chapter should help you decide if wind is an option for you and if you have sufficient resources to make it work. It will also help you determine which type of wind turbine and wind energy system is right for you, and it will help you understand the importance of tall towers.

IS WIND POWER IN YOUR FUTURE?

Wind isn’t for everyone. In fact, if you live in a city or town, chances are wind power is not going to be an option for you. Although the wind blows in cities and suburbs — sometimes quite fiercely — in heavily populated, built-up environments, wind flows are often extremely turbulent. That is to say, although the wind blows, it doesn’t flow smoothly. It’s like water in a rapids.

Wind can’t flow smoothly in built-up areas, because there are too many obstructions — trees and buildings — that generate turbulence. Turbulence is pure hell on wind turbines, viciously tearing many of the lighter-weight models apart. (Turbulence is to wind turbines as potholes are to cars.) Even if turbulence weren’t a problem, there’s often not enough room in urban and suburban neighborhoods to install even the smallest wind turbines. And even if there is room, chances are neighbors will complain, saying the turbine is unsightly. Or city officials might tell you that wind turbines violate height ordinances, which restrict structures to 35 feet.

Wind power is primarily useful as a source of electrical energy in rural areas on lots of one acre or more, preferably two or more, but then only in locations where there are no ordinances that prohibit installation of wind turbines. Even though that limits the potential for residential wind energy, there are still plenty of suitable sites. According to Small Wind Electric Systems published by the US DOE, “Twenty-one million homes in the United States are built on one-acre and larger sites.” So, about 10 percent of the US population could theoretically take advantage of wind energy. But that number may be exaggerated. Wind power will work only for those who live in rural areas with sufficient wind resources. I’ve found that it is difficult to site wind turbines on small lots. You need at least two acres, preferably more, to find a suitable location — one that is far enough away from neighbors and roadways, buildings, and electric lines. If you live in a city or town, though, don’t be disheartened. You can still power your home with wind energy by buying wind power from your local utility. I’ll explain how at the end of this chapter.

WIND POWER: A BRIEF HISTORY

Unbeknownst to many, winds are generated by solar energy. For example, in coastal areas, offshore winds are created by sunlight warming the land masses. Hot air, created when sunlight strikes the land, rises. Cool air from nearby water bodies — large lakes or the ocean — rushes in to fill the gap, creating fairly reliable winds.

Even large air movements across entire continents are driven by the differential heating of the Earth’s surface, which is cooler at the poles than at the equator. Hot air rises at the equator and cooler air from the poles moves in to replace it. The result is huge air circulation patterns — what meteorologists refer to as prevailing winds.

Humans have tapped the power of wind energy for centuries, first to power sailing vessels and later to grind grain and pump water. It is believed that the very first wind generators were used in Persia in the fifth century AD. Wind turbines spread from the Middle East to Europe in the 12th century AD. From Europe, wind technology spread to North America; by the late 1800s, there were thousands of windmills in Europe and North America in rural settings. From the late 1880s to the early 1900s, more than eight million windmills, most of which were used to pump water for livestock, were installed in the United States, according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (Figure 9-2). Some rural farmers installed electric-generating wind machines, known as wind turbines, to provide electricity for lights, toasters, and radios. In the 1920s, however, American cities began to electrify thanks to the pioneering work of Nikola Tesla, the brilliant scientist who invented equipment that made AC electricity possible.

At first, the electricity that powered cities came from centralized power plants that burned coal. Electric lines strung here and there like spider webs throughout cities delivered electricity to homes, offices, and factories. By the end of the 1920s, North American cities were completely electrified, and oil lamps were a thing of the past. But things were quite different in rural areas. There were no central power plants to deliver electricity to rural residents. And there were no electric lines to bring electricity from cities. Small wind turbines were the sole source of electricity on farms. The US government then set its sights on rural areas, launching the Rural Electrification Program. As a result of this ambitious program, wind power entered a period of steady decline. In fact, farmers were required to tear down their electric-generating wind turbines as a condition of connecting to the new electric grid. Wind energy did not die out completely, though. Many small windmills continued to pump water to fill stock tanks on the Great Plains, and some are even working today. (Some areas of the Midwest weren’t electrified until the 1970s.)

Fig. 9-2: This old windmill, which is still functional today, was once a common sight on the plains of North America, where it was used to pump water for livestock. Its larger cousin, which produces electricity in the background, is now becoming a much more common sight throughout the world.

Then came the 1970s and oil shortages. Although the crises were artificial (the result of the actions of the oil-producing countries rather than actual depletion of Earth’s resources), they fueled tremendous interest in energy self-sufficiency, conservation, and renewable energy. Wind benefited greatly, even though it was largely liquid fuel supplies that were threatened by the oil embargoes of the 1970s.

By the early 1980s, there were 80 companies in the United States manufacturing windmills and wind turbines, including large commercial generators and smaller household-sized units. During this period, several utility companies in California built large wind farms to provide electricity to residents in San Francisco. Unfortunately, early wind turbines were plagued with mechanical problems and frequent breakdowns. Large commercial wind turbines, for example, could only be counted on 60 percent of the time. They were broken down and out of service the rest of the time. The early models were also fairly inefficient, too. These problems, combined with a growing lack of concern over achieving energy independence, caused wind power to decline once again. Moreover, because of wind energy’s bad reputation, many people lost interest in this important technology, and some people today continue to view wind power with undeserved skepticism. However, convinced of wind’s importance, several manufacturers tackled the technological problems that arose in the 1970s and early 1980s and have greatly improved their products.

Thanks to the efforts of these manufacturers, often assisted by the National Renewable Energy Lab in Golden, Colorado, the efficiency of large commercial wind turbines has increased, climbing two or three times above efficiencies achieved in the 1970s and early 1980s. Reliability has increased as well, rising from 60 percent to an astounding 97 to 99 percent. Small wind generator manufacturers like Bergey (based in Oklahoma) improved the design of their turbines, simplifying them and getting rid of parts, like the brushes, that required frequent replacement. These improvements have created a resurgence in wind power production. Today, wind power is the fastest-growing source of energy in the world.

UNDERSTANDING WIND GENERATORS

Wind generators go by several names: wind turbines, wind machines, and wind plants. The term windmills is generally reserved for water-pumping wind machines.

Residential wind generators, both large and small, have the same three basic components: (1) a blade assembly that turns in the wind, commonly referred to as a rotor; (2) a shaft that connects to the rotor and rotates when the blades turn; and (3) a generator, a device that produces electricity (Figure 9-3). Many modern wind turbine manufacturers now directly connect the rotor to the generator, eliminating the shaft.

Fig. 9-3: Anatomy of a wind turbine.

Fig. 9-4: Two types of wind turbine are in use today: the horizontal axis turbine shown above, and the much less common vertical axis turbine below.

Wind turbines exist in two basic varieties: horizontal axis units and vertical axis units, as shown in Figure 9-4. Horizontal axis units are the most widely used in household-sized wind systems. Vertical axis wind turbines, which are wildly popular among newcomers and new inventors, have blades that resemble big egg beaters. When wind strikes the blades, they rotate around a vertical shaft. Cool as they are — and there are many very neat designs — these turbines are typically mounted on short towers, where there’s very little wind. They’re also less efficient than horizontal axis wind turbines. As a result, they’re not typically worth the investment.

Because horizontal axis wind turbines are the main players in home wind energy systems, we’ll focus our attention on them. From this point on, when I use the term wind turbine, I’ll be referring to horizontal axis turbines. The turbines we’ll be studying are typically used to provide backup power or to power homes, small businesses, or farms and ranches. Those wind turbines that are designed for battery-based systems are referred to as battery-charging turbines. Those that are designed for grid connection are known as batteryless grid-tied turbines.

A horizontal axis wind turbine is equipped with two or three blades, three being the most commonly used and the most desirable: the use of three blades results in less wear and tear on the generator in shifting winds and results in a more durable, and hence reliable, wind turbine. Blades are typically made of highly durable plastic, fiberglass, or rarely wood with a urethane coating. Many blades come with vinyl or polyurethane tape to protect the leading edge of the blade from wear. The blades of a wind turbine and the central hub to which they are attached are called the rotor. This is the “collector” of the wind turbine. The rotors of wind turbines capture kinetic energy from the wind and convert it into rotating mechanical energy in the form of a spinning shaft. The spinning shaft is attached to the generator. It converts mechanical energy into electrical energy.

Several types of generators are found in household-sized wind turbines. The most common is known as a permanent magnet alternator. They are called permanent magnet alternators because they contain real magnets (as opposed to electromagnets). When the blades of a wind turbine spin, the magnets typically rotate around a number of tightly coiled copper wires, called windings. The movement of the magnetic field past the windings causes electricity to be produced inside the windings. (If you remember your high school physics, moving an electrical coil through a magnetic field creates an electrical current in the wires.)

Wind turbines produce “wild” AC electricity. This is alternating current electricity whose voltage and frequency (cycles per second) vary with the speed of the spinning blades (rpm) and thus the wind speed. Wires attached to the alternator transport the wild AC electricity to a device known as an inverter/controller. The controller converts the wild AC to DC. The inverter converts it back to 60 cycle per second 120-volt AC electricity. (You can learn more about this process in my book, Power from the Wind.)

WIND SYSTEMS:THREE BASIC OPTIONS

Like solar electric systems, wind systems fall into three basic categories: (1) grid-connected, (2) grid-connected with battery storage, or (3) off-grid. As you may recall from Chapter 8, a grid-connected system consists of three main components: (1) a technology that captures some form of renewable energy, in this case, a wind turbine; (2) an inverter, and (3) a main service panel or breaker box. As just noted, AC electricity produced by the wind turbine is converted to DC by the controller inside the inverter, and then is converted to AC electricity. It flows to the main service panel. From here it travels to various active circuits to power devices that consume electricity, known as loads. As in a grid-connected PV system, excess power flows onto the grid, and may be “banked” as a credit on your utility bill. When the wind isn’t blowing, the electricity you need to power your home comes from the grid. Because the grid is your “storage battery,” a grid outage will result in a power outage in your home even if the wind is blowing. This is due to the design of the inverters. (For more details, read the section on grid-connected solar electric systems in Chapter 8.)

If you want to store electricity for emergency use — for example, to protect your home, office, or farm from occasional outages — you can install a battery bank for backup power. In these systems, the batteries are kept full all the time, in case there’s an outage. If a blackout occurs, the inverter converts to battery operation, and DC electricity is drawn from the batteries. The inverter converts the DC into AC, thus supplying electricity to your home to keep the refrigerator running and lights burning. In most grid-connected systems with battery backup, the size of the battery bank is quite small — only enough to supply critical loads during power outages. (For more details, check out the section on grid-connected systems with battery backup in Chapter 8.)

Your third option is an off-grid system, that is, a system that provides 100 percent of your electricity. Off-grid systems are not connected to the electrical grid. Because of this, you cannot send surplus to the grid in times of excess production, nor can you draw from the grid in times of need. In off-grid systems, surplus electricity is stored in a bank of batteries, usually lead acid batteries. (This battery bank is much larger than in the previous system.) Electrical demand during windless periods is satisfied by electricity stored in the batteries, as in an off-grid PV system. A backup electrical generator may also be required. (Again, you can refer to Chapter 8 if you need to brush up on off-grid systems.)

Hybrid Systems

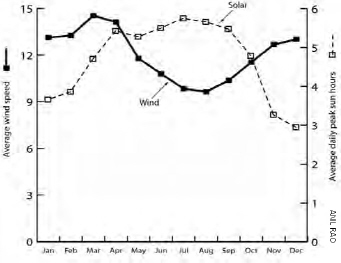

Winds tend to blow in the fall, winter, and spring, then die down over the summer. Because of this, homeowners and business owners who want to generate all of their electricity from renewable sources often install hybrid systems. A hybrid system is a renewable energy system that combines a wind turbine with solar electricity (PVs) or some other renewable energy technology. PVs and wind work particularly well together in many parts of the world because, in many locations, winds pick up in September or October, and continue through April or May. The strongest winds occur between November and March. Sunlight, on the other hand, tends to be strongest in the summer — the period when winds are weakest (Figure 9-5). A hybrid system consisting of a wind turbine and PV array can supply 100 percent of a family’s, business’s, or farm’s electrical needs. During the summer, the PV system provides most of the electricity. The wind turbine is the backup source. During much of the rest of the year, the wind system produces most of the electricity, with the PV array providing supplemental power.

Fig. 9-5: Wind and solar resources are often complementary, as shown here and explained in the text.

Although wind and solar electricity work well together and can provide virtually all of your electricity, you may still need to install a backup generator to supply electrical energy in periods of low wind and low sunshine. (Or, you can simply cut back during these periods.) You also need a gen-set to maintain batteries in peak condition, a topic discussed in Chapter 8.

IS WIND ENERGY APPROPRIATE WHERE YOU LIVE?

Before you invest too much time learning about wind generators and wind energy systems, it is important to ask a key question: Do you have enough wind energy in your location to make an investment worth the money?

Assessing Your Wind Resource

Wind is the clean, free fuel that powers wind turbines. In order for a system to make sense economically, you need a site with sufficient wind. Most systems for homes and farms require an average annual wind speed at ground level of 7 to 9 miles per hour. The higher, the better.

This does not mean that wind speeds need to blow at 7 to 9 miles per hour year round. It means they need to average 7 to 9 miles per hour at ground level. However, wind turbines are not mounted at ground level. They’re typically mounted on sturdy towers 80 to 120 feet tall — sometimes even higher. At these heights, winds blows at higher speeds. For example, a wind blowing at 8 miles per hour at ground level could be blowing at about 13 or 14 miles per hour at 100 feet above ground. (Winds also blow more smoothly at this height because there is less turbulence.) Slight increases in wind speed dramatically increase the amount of power available from the wind. For example, increasing wind speed from just 8 to 10 miles per hour (a 25 percent increase) will increase the power available by 100 percent! The more powerful the wind, the more electricity a wind turbine can produce.

As a rule, the areas with the best wind resources in North America tend to be along seacoasts, on ridgelines, on the Great Plains, and along the Great Lakes. The northeastern United States and the deserts of the southwest are also excellent wind sites. That said, many other areas have sufficient wind resources to make a wind system a viable option. Before even considering installing a wind system, you should assess your site very carefully — or better yet, hire a professional wind site assessor to do the job for you.

To assess the suitability of your location, you can begin by taking a look at a state wind map. You’ll find your state’s map on the Wind Powering America website (windpoweringamerica.gov/). The map you will find there shows average wind speeds, but often at 165 to 198 feet (50 to 60 meters) above the surface of the Earth. Wind turbines are typically a bit lower, so a wind site assessor will extrapolate downward using a mathematical equation to determine the average wind speed at the hub height of the turbine and tower you are thinking about installing. I present this information in my book, Power from the Wind and in my courses on wind site assessment. In Canada, you may want to check out the Canadian Wind Atlas at windatlas.ca/en/maps.php.

Don’t make a decision based on a map, however, because local terrain may cause the wind resource at a specific site to differ considerably from estimates. Wind resources often vary significantly over an area of just a few miles because of hills and valleys, ridges and other factors. If you live in a valley, for instance, your average wind speed will probably be much lower than indicated by the map. If you live on top of a hill and aren’t surrounded by tall trees, the average wind speed may be higher than the wind maps indicate. This is why you should hire a certified wind site assessor. Using some sophisticated tools and websites, he or she can estimate what the actual wind speed is.

When I do wind site assessments, I obtain my data from NASA’s website, Surface Meteorology and Solar Energy. This site allows you to enter the height of the proposed tower and will give you an average expected wind speed for each month and for the year. Be sure to examine average wind speed by month, so you know how much wind is available during different parts of the year. This is especially important if you are planning on installing a wind/PV hybrid system.

If you or the wind site assessor determines your site is suitable for wind — that is, the average wind speed is sufficient — you need to determine if there is a location on your property where you can install a tower so that the turbine will fly high enough above all obstructions. The rule of thumb is that a wind turbine should be located so the entire rotor is at least 30 feet above the closest object within 500 feet. If the tallest object is a tree, take into account tree growth. As an example, suppose your property had a 50-foot barn, a 60-foot silo, and a 55-foot tree that matures at 75 feet. What should the hub height of the turbine be?

To determine hub height, start with the 30-foot rule. The blades of the rotor should be at least 30 feet above the tallest object within 500 feet to reach the smoothest laminar winds (winds that blow without turbulence). In this case, the silo is the tallest object, but the tree will grow to 75 feet. The rotor should therefore be located 105 feet above the mature height of the tree. If the blades on the turbine are 10 feet long, the hub height (the height of the top of the tower where the hub of the rotor is located) should be 115 feet. Since towers come in 20 foot increments, your tower will need to be 120 feet tall.

SELECTING A WIND GENERATOR AND TOWER

If wind is a viable option for you, you’ll next need to determine which turbine and tower to buy. You’ve got lots of choices. This decision typically hinges on two basic considerations: how much electricity you want to generate from the wind and how much money you have to spend. As you shall soon see, there are hidden traps for those who don’t shop carefully. I’ll explain how you can avoid these traps in this section.

Choosing a Wind Generator

As just noted, choosing a wind generator can be tricky. There are numerous manufacturers and numerous models to choose from, ranging from 400-watt to 20,000-watt units (see sidebar, “Wind Turbine: Which Size is Right for Your Home?”). Moreover, there are many different factors to consider when making a decision, among them rotor size, cut-in wind speed, rated output, swept area, weight, and price. There’s also the issue of sound and reliability. Finding information on the latter may be difficult. As you shall soon discover, not all of the information provided on wind turbines by manufacturers and retailers is useful. Bear in mind, though, if you are dealing with local wind energy suppliers/installers, they can often ease the pain a bit. A reliable supplier/installer, for example, typically recommends a few models with which he or she has had success. Be sure to hire someone whose opinions are based on experience — not what they’ve read in the product literature or been told by company sales staff.

Wind Turbine:

Which Size is Right for Your Home?

Wind generators for use in homes, on farms and ranches, and in small businesses, come in many sizes, ranging from 400 watts to 20,000 watts. This measurement is their output at a certain wind speed, known as their rated wind speed, and serves as a rough guide for selecting a turbine. Generally, the 400- to 1,000-watt turbines only supply 40 to 200 kWh of electricity per month, and only in areas with good, solid 12-mile-per-hour average wind speeds. Most homes in America consume around 750 to 1,000 kilowatt-hours per month. All-electric homes could easily consume 1,500 to 2,500 kWh per month, as would a small business or a farm or ranch operation.

Unless your home or business is super-efficient, you will need a larger wind turbine, around 2,500 to 6,000 watts. Even then, you’ll need to use electricity efficiently unless you install one of the largest and costliest models with rated power values of 10,000 kWh. Or you could install a hybrid system: a smaller wind generator with a PV array.

Wind turbines can be purchased through national suppliers like Gaiam Real Goods or online suppliers. Although such sources typically carry models that work well for them, you should know as much as you can about wind turbines before putting your money down. This section will help you understand the most important factors you’ll need to consider when shopping for a reliable wind turbine. If you want to do a detailed analysis of your options before talking to a local dealer/installer or before perusing catalogs of various online suppliers, I strongly recommend that you read my books Wind Energy Basics or Power from the Wind, or attend a few small wind energy classes.

Swept Area

As you may recall, the spinning blade assembly is known as the rotor. It is the collector of wind. That is, it converts the movement of air passing by the blades into mechanical energy, which is, in turn, converted into electrical energy by the alternator. As a general rule, the larger the rotor, the more electricity it will produce. As Mick Sagrillo points out in his piece in Home Power, a wind generator’s rotor size “is a pretty good measure of how much electricity a wind generator can produce.”Although other features such as the efficiency of the generator and the design of the blades can influence efficiency, Sagrillo argues that “they pale when compared to the overall influence of the size of the rotor.” With wind turbines, size does matter.

Rotor size is determined by the length of the blades, which represent the radius of the circle described by the spinning blades. The area of that circle is known as the swept area. The swept area is measured in square feet or square meters. Figure 9-6 illustrates the differences in swept area of three household-sized wind turbines. You can quickly pick out the high-energy models just by looking at the swept area. This is the one factor that allows for easy comparison of different models.

Fig. 9-6: The swept area varies dramatically from one wind turbine to the next. By and large, you should choose the model with the greatest swept area. It will produce the most electricity at your site.

Cut-In Speed

Household-sized wind turbines start producing electricity at wind speeds in the range of six to eight miles per hour. This is known as the cut-in speed. Unfortunately, they don’t start producing useful amounts of electricity until wind speeds of 10 to 12 miles per hour. As a result, cut-in speed is pretty meaningless. Nevertheless, many people are impressed by turbines with low cut-in speeds. Don’t be one of them. Although these turbines may start producing some electricity at low wind speeds, it won’t be a significant amount.

Rated Output

As already discussed, PV modules are compared by their output — the amount of electricity they produce under standard conditions. Many modules these days produce 200 watts, give or take a few, under standard test conditions. Wind turbine manufacturers also rate the output of their turbines in watts. Bergey Windpower’s BWC XL.1, for instance, has a rated power output of 1,000 watts. So does Southwest Windpower’s Whisper 200.

The trouble is, there are no set standards for determining rated output in the wind industry, as there are in the PV industry. (This could change soon, as efforts are underway to implement standards for rating wind turbines.) For example, the two manufacturers just mentioned rate their wind turbines at different wind speeds (called rated wind speeds). Bergey rates their turbine at 24.6 mph, while Southwest Windpower rates theirs at 26 mph. So which one is better? Because they are rated at different wind speeds, you can’t really say. You would think that the wind turbine that produces 1,000 watts at the lowest wind speed would be the best buy. But not in this case. To make a decision, you’d be better off looking at the swept area. In this case, the swept area of the Bergey is 52.8 square feet and the Whisper is 78.5 square feet. Which one will produce the most electricity for you? The model with the largest swept area. As my friend and wind mentor Mick Sagrillo says: “While comparing PVs based on rated wattage makes for great cost comparisons, comparing rated outputs is a poor way to compare wind generators. You are far better off comparing swept areas or the kWh per month of electricity the different systems will produce at different average wind speeds.” In the example just given, the Bergey produces 115 kWh per month in an area with 10 mph wind, while the Whisper produces 125 kWh per month. The monthly energy output at various wind speeds is a much better criterion. I typically compare wind turbines on the basis of annual energy output, or AEO, at various wind speeds. This tells you which turbine will produce the most energy.

Governing System

All wind turbines come with a mechanism to prevent the generator from burning out in high winds. Why?

High winds increase the rpm of a wind turbine, which increases the amount of power produced. This is generally desirable. However, really high rpm can lead to overheating and burnout. The windings can get so hot they melt. To prevent this problem, manufacturers install some type of governing system also known as over-speed control.

One form of overspeed control simply turns the blades out of the wind so they slow down or completely stop spinning. The blades may tilt up and out of the wind. This is referred to as top furling, and is shown in Figure 9-7a. Or, the turbine may fold, so the blades turn out of the wind. This is referred to as side furling, and is shown in Figure 9-7b. Both mechanisms reduce the frontal area of the turbine, that is, the amount of rotor surface facing the wind. This, in turn, reduces the swept area, and slows the blades down to prevent the turbine from spinning too fast.

The other governing system changes the blade pitch, that is, the angle of the blades, so they no longer intercept the wind as efficiently. This causes the rotor to spin at a slower rate. Although blade pitch governing systems allow wind turbines to continue to produce power, they require more moving parts. As a rule, the more moving parts you have, the more maintenance. Talk to local installers for their recommendations.

Fig. 9-7 a and b: Overspeed control. (a) This wind turbine from North Wind Power top furls. Notice how the rotor rotates upward to reduce swept area and prevent the machine from spinning too fast. (b) This wind turbine side furls to achieve the same effect. Side furling is more common.

Shut-Down Mechanism

Most wind turbine manufacturers include a shut-down mechanism — a mechanical or electrical device that allows an operator to shut a wind generator off. This is important because it allows the owner to repair or maintain the wind turbine without fear of injury. It also provides a means to shut the wind turbine down when a violent storm is approaching. Shut-down mechanisms come in many varieties, from disc and dynamic brakes to folding tails — tails that fold in such a way that the wind turbine is forced out of the wind and the blades stop rotating. The shut-down mechanism of a wind turbine is a key factor to consider when shopping for a wind turbine.

Unfortunately very few turbines have reliable shut-down mechanisms. The most effective seem to be those that allow the operator to crank the tail out of the wind or engage a disc brake. This is achieved by turning a crank at the base of the tower. The crank is attached to a cable that either engages the brake or causes the wind turbine to fold on itself, which pulls the blades out of the wind.

Sound Levels

Wind turbines are not, by their very nature, quiet, although some models are significantly quieter than others. In fact, some of them are so quiet, you have to look to see if they are actually spinning. Sound is primarily generated by the blades cutting through the air and the spinning of the internal components of the generator.

As a general rule, the blades of lightweight wind generators spin faster than blades of heavier units. The higher the rpm of the blades at the rated wind speed, the more sound a turbine will make.

Fortunately for all concerned, the highest sound levels occur at high wind speeds, when background noise increases as well — for example, when the leaves and branches of trees are being blown by the wind. Also, wind blows by your ears, making it more difficult to hear. Also, fortunate is the fact that sound drops off fairly quickly with distance. Thus, the taller the tower, the less noise you will hear. Even so, I can still hear my 2.5 kW Skystream any time it is spinning, except in really strong winds which drown out the turbine, anywhere on my 50-acre educational center/farm — and it’s on a 126-foot tower. So, be sure to listen to the turbine or turbines you are thinking about buying before you buy to assess sound levels. To minimize disturbance, install a turbine as far away as possible from your home and neighbor’s homes.

Durability

The durability of a wind turbine is important criterion when shopping. The more durable the machine, the longer it will last, the less maintenance it will require, and the more electricity it will produce. In short, a more durable turbine is a better investment of your time and money.

You might think that one metric published by wind turbine manufacturers — maximum design wind speed — would be a good indicator of durability. However, as Mick Sagrillo says, “it has little bearing on the expected life of a wind generator.”

Sagrillo points out that wind generators are designed to survive wind speeds of 120 mph or more, but they are not necessarily tested at these speeds — or repeatedly tested at these speeds — to see if the claims really hold up over time. And, in fact, more turbines are damaged by turbulence than high winds.

Sagrillo argues that the best criterion for durability is tower top weight: how much the unit weighs. “My experience,” says Sagrillo, “is that heavy duty wind generators survive, and light duty turbines do not.” Therefore, even though most wind turbines are rated for 120 mph or greater maximum wind speeds,“ experience indicates that many of the lighter turbines cannot handle sites with heavier winds or turbulence.” Of the two models already mentioned, the Bergey XL.1 weighs 75 pounds and the Whisper 200 weighs 65 pounds. Neither is very heavy, but the Bergey has a reputation for being a very durable wind turbine. However, says Sagrillo, “Be forewarned! Weight … will be reflected in the price.” As a rule, the heavier the unit, the more it will cost.

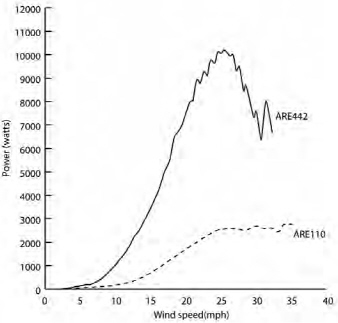

When you are shopping for wind turbines, you will often encounter power curves, like the one shown in Figure 9-8. A power curve is a graph that plots the power production in watts for a given wind turbine at different wind speeds. While they are nice to look at, they don’t really help you very much in making a decision. Although 10,000 watts peak power on the curve looks impressive, remember that most turbines operate at the left end of the power curve — in slower, 10 to 15 mph winds. As you will see by looking at power curves, the output of a turbine at these wind speeds is usually pretty low. Again, the more valuable measures are swept area, annual energy (kWh) production per year at various average wind speeds, and weight.

Purchasing a Tower

A wind turbine constitutes a major expense in any wind system, but that cost is often rivaled by the cost of the tower. In this section, we’ll examine towers.

Towers come in three basic varieties: free-standing, guyed, and tilt-up. Each type has a couple of subtypes.

Free-Standing Towers

Free-standing towers are those that require no additional support: they are self-supporting. Because they have a relatively small footprint, they are ideal for applications where space is limited. For example, if you only have an acre of land.

The most common free-standing tower is the lattice or truss tower, like the one shown in Figure 9-9. Lattice towers resemble the latticework of arbors. The Eiffel Tower in Paris is an example of a lattice structure. Lattice towers are secured to a massive foundation and are engineered to withstand powerful winds. Because of the large amount of metal that goes into them and because of the need for a sturdy anchoring foundation, they are one of the most expensive tower options.

Fig. 9-8: This power curve shows the output of an ARE110 and an ARE442 wind turbine in watts (power) at various wind speeds. Note that wind turbines typically operate at the low end of the curve, in winds under 20 miles per hour.

Fig. 9-9: The lattice or truss tower is strong and durable and an excellent choice for mounting larger wind turbines. It can be supported by guy wires, if necessary.

Free-standing lattice towers are typically installed in 20-foot sections. The sections are usually preassembled and welded or bolted together prior to delivery. When the sections arrive, they are bolted together on the ground, then lifted onto the foundation via a crane, and bolted in place. Some installers assemble lattice towers in the upright position piece by piece using a device known as a vertical gin pole. This is risky and time-consuming and generally avoided by experienced installers. Yet another method is to install a lattice tower with a hinge at the base. The tower is assembled on the ground, the wind turbine is attached, and then the tower is tilted up using a crane, thanks to the hinged base.

Another option for a free-standing tower is a monopole. This tower consists of rigid metal steel pipe. It is assembled on the ground, 20 feet at a time, then lifted and bolted onto a hefty concrete foundation using a crane. Monopole towers require a lot of steel and a very large foundation; therefore, they are the most expensive type of tower.

Whatever choice you make, be sure that the tower is strong enough to withstand both the winds in your area and the weight of the wind turbine — both of these can be quite substantial. Several of the largest home-sized wind turbines weigh around 1,000 to 1,500 pounds. The Jacobs 31-20, admittedly the heavyweight of the residential- or business-sized units, weighs 2,500 pounds!

The Mathematics of Wind Power

The power available to a wind turbine (and thus, its electrical output) depends on many factors: the most important are air density, swept area of the rotor, and wind velocity. The relationship among these factors is expressed by the mathematical equation P = ½ d x A x V3. (In this equation, P stands for power in watts; d stands for air density. A is the swept area of the rotor, and V is wind speed.) What this equation tells us is that the greater the density of the air, the swept area, and the wind speed, the more power is available in the wind (measured in watts).

Air density varies with humidity levels and elevation above sea level. Although you can’t control air density, it is important to understand the role it plays in wind power generation. For example, air is less dense at higher elevations, so if you live in the mountains, you should lower your estimates of your wind turbine’s expected output. Don’t expect it to produce as much electricity as it would at a lower elevation at any given wind speed. Also, because air is a bit denser in the winter than in the summer, you can expect greater output from a wind turbine in the winter — about 13 percent more. This is especially important to those who are installing hybrid wind/PV systems.

Although you can’t control air density, you can control swept area and wind velocity. Swept area, as explained earlier, is determined by rotor size. The bigger the rotor, the greater the swept area. Select a wind turbine with the largest possible swept area.

You can also affect wind speed by choosing the best site and installing your wind turbine on the tallest tower possible. This allows you to raise the wind turbine into the fastest winds and will have an enormous effect on electrical production. For example, by doubling the wind speed from 8 miles per hour to 16 miles per hour, power production increases by 800 percent!

Guyed Towers

Guyed towers typically consist of steel pipe or lattice uprights supported by cables called guy wires, a.k.a. guy cables, that run from the tower to anchors in the ground (Figure 9-10). (Please note that it is guy wires or cables, not guide wires.) Guyed towers are the cheapest towers and are therefore very widely used in the small wind industry. Steel pipe can be used for the masts of all household-sized wind turbines. The steel pipes are assembled section by section, secured by bolts or slipped together, then erected using a crane.

For larger small wind turbines, the lattice tower is often the tower of choice. They’re strong, mass-produced for the telecommunications industry and therefore widely available, and they are cheaper than other options. They’re also available in different strengths. Like free-standing lattice towers, they can be assembled in the horizontal position on the ground then tilted into place, or they can be assembled upright, one section at a time or in their entirety, using a crane.

Fig. 9-10: Guy wires help hold many towers in place. Wires are installed in groups of three to four. Typically, each segment of the tower is guyed.

In all guyed towers, strong steel cable is attached to the tower and anchored in the ground using an assortment of anchoring mechanisms, depending on the soil type. Stranded wire cable ranging from one quarter to one half inch is typically used.

Installers use three guy wires for each section of the tower, located 120 degrees apart. Manufacturers typically specify guy radius — that is, how far out the anchors for the guy wires need to be for optimal strength.

Tower Kits

If all of this seems a bit daunting, don’t be dismayed. A professional installer will design a system for you, order the components, assemble the tower, mount your wind turbine, and raise the tower … for a price, of course. If you’d like to try your hand at this, you’ll be happy to know that several manufacturers sell tower kits designed and engineered specifically for their wind turbines. Southwest Windpower, Lake Michigan Wind and Sun, Xzeres (formerly Abundant Renewable Energy), and Bergey, for instance, all sell tower kits. Because it doesn’t make sense to ship fairly inexpensive, but very heavy and bulky steel tubing long distances, manufacturers typically provide all of the materials you need except the pipe. These kits may not include the anchors because the type of anchor varies from one location to another, depending on the soil type. You can purchase steel pipe locally at a steel and pipe supplier. You can purchase the anchors from the tower kit manufacturer, although most anchors are made of steel-reinforced concrete poured on site. To learn more about towers, you can read my book, Power from the Wind, or attend a workshop on small wind energy systems such as those I offer at The Evergreen Institute in Missouri.

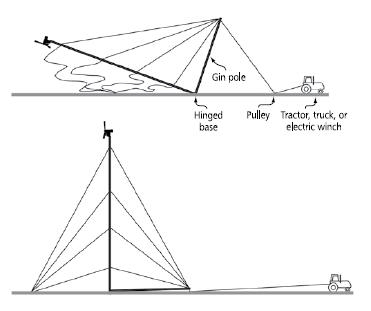

Fig. 9-11: The gin pole shown here allows an installer to tip a large tower into place without an expensive crane.

Fig. 9-12: The gin pole and mast of the tower are connected to a hinge, which permits the tower to tilt up and down.

Tilt-Up Towers

The third type of tower is the guyed tilt-up tower. Unlike free-standing and fixed guyed towers, guyed tilt-up towers can be raised and lowered to perform inspection, maintenance, and repair.

Tilt-up, guyed towers come in many heights — up to around 130 feet (40 meters). They are most often made from steel pipe, although guyed tilt-up lattice towers are also available. Guyed tilt-up towers require four sets of guy cables every twenty to forty feet, rather than three in fixed guyed towers. In addition, the guy cables are located 90 degrees apart. As in the fixed, guyed tower, guy cables of guyed tilt-up towers provide support. The fourth set of cables, however, enables workers to safely raise and lower the tower. Without the fourth set of cables, the tower would topple as it was tilted into place or lowered to the ground for servicing.

As illustrated in Figure 9-11, a tilt-up tower is raised and lowered with the aid of a gin pole. This steel pipe (or a section of lattice tower) is usually permanently attached to the base of the tower at a right angle (a 90° angle) to the mast. It serves as a lever arm that allows the tower to be tilted up and down for inspection, maintenance, and repair.

As shown in Figure 9-12, the gin pole is attached to the base of the tower which is attached to the hinged joint. When the tower is down — that is, lying on the ground and ready to be raised — the gin pole sticks straight up. When the tower is vertical, the gin pole lies near and parallel to the ground. As illustrated in Figure 9-11, a steel cable connects the free end of the gin pole to a lifting device such as a tractor or better yet, an electric winch, which is used to raise and lower the tower (discussed shortly).

Tips on Finding a Supplier or Installer

If wind is a viable option for you — that is, you have enough wind in your area and can afford to buy and install a turbine — you have two obvious options for proceeding. You can purchase and install the equipment yourself, or you can hire a professional. If you select the first route, you’ll need to do a lot more in-depth research. You’ll also need to read up on installation. You’d also be wise to take a course on wind energy that includes hands-on installation work. A couple of installations would be even better. Be careful. Installation can be dangerous to people and equipment. You don’t want a $5,000 to $25,000 wind turbine to come crashing down because you made a mistake during installation.

When purchasing a wind turbine, be sure to check out warranties and read the fine print. Most warranties are for five years, although a few manufacturers recently boosted theirs to 10 years. Also check out how long the companies you are considering have been in business.

The second option is to go with a local supplier/installer. Their expertise can be highly valuable. A local expert can also help you troubleshoot problems once the system is up and running and can repair and maintain your system, if need be.

Yes, you read that right.

Wind energy systems need periodic maintenance — like any mechanical and electrical system. Wind turbines and towers, for example, must be inspected periodically — usually twice a year. If problems are encountered, they must be corrected. Some larger wind turbines may even need grease or oil changes. Battery-based systems require even more maintenance, a topic briefly described in Chapter 8 and more thoroughly covered in my book, Power from the Wind. If you are not into maintenance, don’t buy a wind turbine.

Manufacturers have made tremendous strides in improving the quality of their wind generators since the early 1980s, mostly by simplifying the turbines and using stronger, more durable materials, such as carbon-reinforced blades and new metal alloys. However, don’t forget: wind turbines are exposed to extreme weather and amazing stresses (heat and cold, snow, ice, and fierce wind). Fortunately, many problems that arise are simple ones that can be fixed in seconds, like loose bolts. If left unattended, though, small problems can lead to catastrophic failures.

Even blades require maintenance. Some need to be repainted from time to time. Protective tape on the leading edges of blades protects them against grit and insects in the air. The tape will need to be replaced every so often. And, of course, bearings will eventually wear out and need replacement.

To maintain a wind generator, you’ll either need to periodically ascend the tower using a climbing harness — very carefully, so as not to fall — or you’ll need to lower the turbine to ground level (the main reason for installing a tilt-up tower). After 20 years of successful operation, the guts of the wind turbine may even have to be ripped out and replaced. As Mick Sagrillo points out, “The life of a wind generator is directly related to the owner’s involvement with the system and its maintenance.” If you expect a wind turbine to work doggedly in its harsh environment without maintenance, wind power is not for you. That’s a pretty unrealistic expectation.

Some Tips on Installing a Wind Turbine

To be effective, wind turbines need to be installed in a good, windy site, usually upwind of buildings and other obstructions. If installed downwind, turbines need to be significantly past the wind shadow — the turbulent eddy created by obstructions. The best wind, as already noted, is the smoothest and strongest wind, which is 80 feet or more above the ground. The higher, the better. To be effective, a wind turbine typically needs to be erected on a tower at least 80 to 120 feet above ground level to access the best wind and, as already noted, the entire rotor must be at least 30 feet above the closest obstruction or treeline within 500 feet. Whatever you do, do not mount a wind turbine on a roof or against a building — even if a supplier provides special mounts for such applications. The vibrations will be conducted into the building and are very annoying. Sadly, I know this to be true because I tried it … just to test it, of course. (Yeah, right!) Moreover, if the turbine is on or against a building, the building itself will create air turbulence that will lower performance and increase wear and tear on the turbine.

While we’re on this topic, be sure to mount your wind generator as close to the inverter as possible. This is important for two reasons: to reduce line loss and to reduce the need for larger (and more costly) electrical wire. Installation manuals will help you determine the gauge wire you will need.

Before you decide to install your own wind generator, be sure to read more on the subject.

FINANCIAL MATTERS

Like a good salesperson, I’ve given you the scoop on wind power before I drop the cost bomb. How much does it cost to install a wind turbine?

As noted earlier, wind generators for household use vary from the smallest 1,000-watt turbines to the largest 20,000-watt unit. If you simply want to supplement your electrical energy from the grid, a wind turbine of 1,000- to 3,000-watt rated output might be ideal. When buying, look for models in this range, then compare them using swept area, weight, AEO, and costs. A 1,000- to 3,000-watt wind generator might also work if you live in a tiny cabin, or you are extremely efficient. And it might suffice if you are installing a hybrid system — a combination of wind and PVs — or some other renewable resource such as microhydro (see Chapter 10).

If you want to go off-grid completely and are hoping to supply electricity solely from a wind turbine, you’ll very likely need a larger wind generator — a turbine with a rated power output of more than 3,000 watts — possibly 6,000 to 10,000 watts. It all depends on how much energy you need. Again, whatever you do, be sure to make your home as efficient as possible in its use of electricity first. Small investments in electrical efficiency pay huge dividends by reducing system size and costs.

Also, remember that you get what you pay for. Heavy-duty wind turbines generally cost more but are more durable and will very likely outlast their cheaper, lighter, high-speed cousins. A good heavyweight wind turbine will very likely last 20 years — or more. Its lightweight cousin will last half that time, maybe even only one fourth as long, according to Sagrillo. So, savings on a less expensive model are eaten up by replacement costs.

Another important consideration when designing a wind system is that tower height makes a huge difference in power output. Because power increases dramatically with wind speed and because wind speed increases with height, raising the tower a bit can greatly boost a system’s output. So rather than paying twice as much to purchase a more powerful wind turbine, consider a smaller investment in tower height to increase energy production.

Wind turbine costs vary tremendously. Wind turbines around 1,000 watts rated output cost about $2,500 with a charge controller, although there are some models that cost more than $5,000. Wind turbines ranging from 2,500 to 6,500 watts with charge controllers will run about $9,000 to $20,000. Costs for the largest residential wind turbines — 8,500 to 20,000 watts rated output — are $20,000 to $40,000. But don’t forget the tower, another big expense. Tower prices vary considerably, depending on the height of the tower, type of tower (monopole vs. guyed tilt-up, for instance), and type of material. The most expensive is the free-standing monopole, followed by the free-standing lattice, followed by the tilt-up. The least expensive is the guyed lattice tower. You can easily pay $12,000 to $25,000 for a tower and installation, sometimes more, for a 120-foot tower.

When calculating costs, remember that in the United States the federal government provides a 30 percent federal tax credit for wind systems. The USDA offers a 25 percent grant for wind systems for rural businesses. Very few states and utilities, however, offer financial incentives. Two exceptions are New York State and Wisconsin.

WIND POWER WITHOUT INSTALLING A WIND GENERATOR

If a wind generator is not right for you, don’t fret. Many utilities offer green power to their customers. Green power is electricity generated from renewable sources, mostly gigantic wind turbines on commercial wind farms, like those shown in Figure 9-13. Green power may be produced by other renewable sources as well, but wind is the dominant source. It’s the cheapest and most widely developed commercial renewable energy source in the world, other than hydropower from hydroelectric plants on rivers. In Colorado, the local utility offers its customers an option to purchase blocks of wind energy from ever-expanding wind farms. Customers can opt to buy as many blocks as they want, provided the company has enough to sell.

Even if the utility company in your area does not have its own wind farm, it may currently be purchasing power from renewable producers and can offer you green energy just the same. At this writing, utilities in at least 36 states in the United States offer some form of green power. What that means is that many US households could choose some type of green power directly from their local utility or through the competitive marketplace. California and Pennsylvania have been the most active markets for green power. (See Blair Swezey and Lori Bird’s article, “Businesses Lead the Green Power Charge” in Solar Today.)

Chances are you’ve heard about green power and already know whether it is available. If not, ask your local utility. As the markets for electricity deregulate, more and more companies will be able to provide power on electrical grids owned by others; you may be able to purchase green power from one of these competitors. Even if it costs a few bucks more each month — and it usually will — it’s well worth it.

If there are no utilities in your area that sell green power, you can still play an active role in this growing industry by purchasing a green tag. A green tag is a small subsidy to power companies producing green power. It supports their green power programs. Bear in mind, however, that you won’t actually receive the electricity. Someone else will, but you will help make it happen. Green tags are sold by a number of companies and go by different names. The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, for example, calls their green tags “Green Power Certificates.” Pacific Gas and Electric sells “Pure Wind Certificates.” Waverly Light and Power in Iowa sells “Iowa Energy Tags.” Big city governments, such as those of Chicago and San Francisco and key federal agencies, such as the EPA, the DOE, and the US Postal Service, are currently making substantial commitments to buy green power. With these advances, it seems very likely that homeowners are going to have ever greater opportunities to purchase green power for themselves.

Fig. 9-13: This large wind turbine in northeastern Colorado is used to create green power for a local municipality.

At the present time, electricity from clean, reliable sources costs a little more; on the other hand, some service charges may be deducted from your bill, reducing the costs. In addition, the cost of wind power is likely to fall in the very near future as more wind turbines go on line and more improvements are made in wind generator technology. Furthermore, we’ve recently seen that while prices for electricity from coal have increased, wind-produced electricity has remained the same.

Remember: good planets are mighty hard to come by. A small investment in environmentally friendly electricity is a small price to pay to create a sustainable way of life and a better future. Investments in renewable energy will also help build stronger economies that resist the potential turmoil caused by declining supplies of conventional fuels.

The Cost of Green Power

Over time, as wind-generated energy becomes more widespread, the price is bound to plummet. Newer turbines are already producing electricity more cheaply than natural gas — at a price only slightly higher than coal.