MICROHYDRO

GENERATING ELECTRICITY FROM RUNNING WATER

Humans have been tapping the power of flowing water for centuries. Early New Englanders, for instance, tapped the power of water flowing in the streams that ran through their towns by installing small dams and water wheels. The water wheels powered the machinery of textile factories and grain mills where wheat was ground into flour used to make bread, a staple of early American life. Hydropower continues to play a pivotal role throughout the world today. Its primary value, however, is as a source of electricity. Today, hydroelectricity constitutes 7 percent of the total electrical generation in the United States, and 21 percent in Canada.

But that’s not hydropower’s only claim to fame.

Hydropower is not only a significant source of energy, it also has the distinction of ranking number one in annual energy production among all renewable energy resources. That is, of all renewable energy sources in the world, it’s the “top dog.” Large-scale hydropower projects, however, are not the main topic of this chapter. Rather, we’ll focus our attention on microhydro — small-scale systems that provide electricity to homes, small farms, ranches, and small businesses.

Yes, even small businesses.

One of the best examples of a business application is the shop run by Don Harris in Santa Cruz, California. Where this pioneer in renewable energy manufactures turbines for microhydro systems. According to Scott Davis, author of Microhydro: Clean Power from Water, “Even at the smallest of scales, water power continues to be a reliable and cost-effective way to generate electrical power with renewable technology.” Although microhydro is a reliable and economical source of electricity for those wishing to go part way or entirely off-grid, it does have its limitations. First and foremost, you need a stream or river nearby — one that has a consistent and sufficient flow and offers sufficient water pressure (more on this shortly) to produce enough electricity to make the investment worthwhile.

Unfortunately, there aren’t that many microhydro sites available worldwide into which homeowners can tap. For this reason, microhydro is of limited use in most countries. However, for those who are lucky enough to live near a suitable stream — usually those living in mountainous or hilly terrain — microhydro offers great promise. Even people in the flatlands can generate electricity from water if there’s a large enough stream nearby that flows at a sufficient rate of speed. It is for these lucky individuals — and for folks who just want to learn more about this fascinating energy source — that this chapter was written.

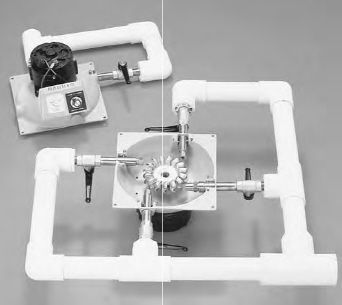

Fig. 9-1: Don Harris, a pioneer in microhydro power in North America, manufactures microhydro turbines/ generators in his shop in the hills outside of Santa Cruz, quite fittingly powered by hydropower.

AN INTRODUCTION TO HYDROELECTRIC SYSTEMS

Hydroelectricity is based on some pretty simple concepts. If you have read the wind power chapter in this book or have studied conventional electrical production by coal, nuclear, or geothermal energy, you’ll see the similarities instantly. In a microhydro system, moving water turns a turbine. The turbine spins a generator. The generator (or alternator) produces electricity. These components are common to all of the electrical generating equipment discussed in this book, except PV modules.

“Many other components may be in a system, but it all begins with the energy … within the moving water,” says Dan New, author of “Intro to Hydropower” published in Home Power magazine, Issues 103–105. (This information can also be found on Dan New’s website canyonhydro.com under “Residential Systems.” Click on the “Guide to Hydropower.”) The energy of moving water is produced by gravity, that magical force that propels water down the slightest of gradients. It is important, however, to point out that water reached the heights from which it flows downward thanks to two other natural forces — evaporation and precipitation.

Water evaporation is triggered by solar energy. Sunlight striking the Earth and various water bodies causes moisture to evaporate, and that is where the flow of water through the hydrological cycle begins. You might say that it is all downhill from that point on. Because of this, hydropower is just another form of solar energy. That mysterious force, gravity, plays its part, too.

As in other renewable energy systems, microhydro systems fall into three broad categories:

(1) off-grid, (2) grid-connected, and (3) grid-connected with battery backup. (These distinctions are outlined in Chapter 8 for those who aren’t familiar with the terms.)

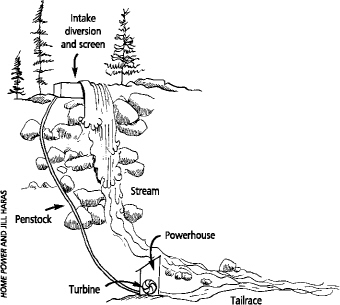

THE ANATOMY OF A MICROHYDRO SYSTEM

Microhydro systems are electrical generating systems for use on a small scale, usually for residential power in remote mountainous terrain. Microhydro is usually “installed” along small streams or rivers close to the buildings where it will be used — the closer the better! To protect the stream and those creatures that depend on it, microhydro systems generally divert only a small portion of the current from the waterway. This water temporarily borrowed from the stream is diverted into a pipe or specially built channel or canal (that typically runs alongside the waterway) to a turbine some distance below the water intake. The turbine is connected to an electrical generator, described shortly.

Microhydro systems exist in two basic configurations: low-head and high-head. (Head refers to water pressure created by the vertical distance water flows, as you shall soon see.) Most homeowners install high-head systems.

The Renewable Energy of Choice

For those who are fortunate enough to have a good site, hydro is really the renewable energy of choice. System component costs are much lower and watts per dollar return is much greater for hydro than for any other renewable source. Microhydro, given the right site, can cost as little as a tenth of a PV system of comparable output. Moreover, hydropower users often are able to run energy-consumptive appliances that would bankrupt a PV-system owner, like large side-by-side refrigerators and electric space heaters.

— John Schaeffer, Solar Living Source Book

High-Head Microhydro

Figure 10-2 shows the basic components of the most widely used microhydro system, the high-head system. As illustrated, this system consists of a specially built water intake structure. It is constructed in a stream or river, usually along its banks, so as to minimize disturbance to the aquatic environment. One of the key components of the water intake structure is a small settling basin that allows grit to precipitate out. (Grit and silt in water can wear out the moving parts of the microhydro turbine.) Another key component of the water intake structure is a screen that removes debris such as leaves and branches that can clog the pipes and the spray nozzles on the turbine. They can also damage the turbine runner (the wheel inside the turbine that spins when struck by water). Water typically flows from the intake structure into a pipeline (called a “penstock” by professionals). The pipe typically runs alongside the river or stream — not in the watercourse itself — to protect the pipe from raging flood waters that can rip it apart. The pipe carries the water downhill to the turbine, usually located in a simple shelter — either a small, sturdy, waterproof vault or a small shed. Water flowing through the turbine causes a wheel (the “runner”) inside the device to turn (Figure 10-3). A steel shaft connects the runner to the generator. When the runner and shaft spin, they cause the inner workings of the generator to spin, producing electricity. (Because the generator in a microhydro system operates like the generators in wind turbines, you might want to check that section out now.)

Fig. 10-2: High-head microhydro systems consist of a water intake structure, a pipeline or penstock, a turbine/generator, and an outlet.

AC and DC Microhydro

Microhydro systems produce both DC and AC power, depending on the design. However, DC systems are by far the most commonly used in small-scale applications.

Water flowing through the turbine housing flows back into the stream. This return flow is referred to as the tailwater. As noted earlier, microhydro systems produce DC and AC electricity depending on the design of the generator. As you may recall from reading previous chapters on solar electric and wind systems, AC electricity powers our homes and offices. As a result, DC electricity produced by the generator in a microhydro system must first be sent to an inverter. It converts the DC electricity produced by the generator to AC power.

The inverter also boosts the voltage of the current from the generator, typically from 12, 24, or 48 volts, depending on the model, to 120/240 volts, which is standard household current.

AC Microhydro Systems

AC microhydro systems produce a form of electricity that can be used directly without conversion. In off-grid systems, the AC electricity will, however, need to be converted back to DC to be stored in a battery bank.

Fig. 10-3: (a) Pelton and (b) Turgo runners.

Low-Head Microhydro

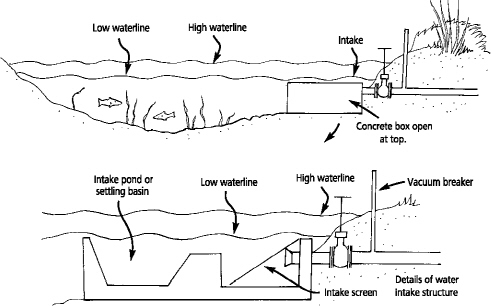

Low-head microhydro systems are a bit simpler than the high-head systems just described. As illustrated in Figure 10-4, they require a screened intake or a small dam across part of a stream or river with a settling basin to allow grit and silt to precipitate out. The intake structure empties into a fairly short diversion canal that delivers water to a vertical draft tube often only ten feet long. A draft tube sends diverted water back into the stream and is where the turbine is located. The water flowing through the system turns a propeller-like turbine. It is connected to a generator that produces electricity. Water is returned directly to the stream. Such systems are often built near small water falls.

ASSESSING THE FEASIBILITY OF YOUR SITE

Before you decide to purchase a microhydro system, you — or better yet, a professional microhydro installer — will need to study your site very carefully to determine whether a system could work and how much electricity it could generate.

Fig. 10-4: A typical water intake structure requires a stilling basin to allow sediment to precipitate out. It also requires a deep pool so that the pipe remains free from ice.

Analyzing Your Electrical Energy Needs

Before you assess the electrical generating capacity of a stream, however, it is important, indeed essential, to analyze your electrical energy needs. This process is described in Chapter 8, so I won’t repeat it here, other than to offer a few reminders. First and foremost, when determining your electrical demand, it is important to be accurate — and generous — in your assessment. Accuracy is vital to your success, but it is often difficult to achieve. Generous estimates are important because most people use a lot more electricity than they think they do.

Why?

When estimating electrical consumption for a new home, people often begin by listing all of the components of their load, that is, their household electrical demand. This includes appliances, lights, fans, pumps, coffee makers, aquariums, and the assortment of other electronic devices they have. They then list how much power each electronic device consumes, and how long the device is used each day.

The problem with this approach is that very few people really know how long they run the TV or the toaster or the microwave each day. So estimates can be pretty inaccurate. If you are installing a system for an existing home or work space, your task is considerably easier: you simply consult your energy bills for the past two or three years to calculate monthly electrical consumption. If you haven’t saved your bills, you can contact your local utility company. They will gladly provide records. Armed with this data, you can arrive at a pretty accurate estimate of the electrical energy demands that your system will need to meet. But what do you do if you are buying a house from someone else? Get on the phone and call the utility and ask for previous utility bills. Bear in mind, however, that previous utility bills, while accurate, represent use by a different household, and may differ dramatically from your use of energy. The previous occupants may have been more miserly or much more extravagant than you — or somewhere in between. Their energy consumption, in short, could be quite different from yours. Before you arrive at a final estimate of electrical consumption, however, remember to trim your own electrical consumption. In so doing, you can dramatically reduce the cost of a renewable energy system. Changes in habits (like shutting off lights when you leave a room) and energy efficiency measures (compact fluorescent lightbulbs and LED lightbulbs, for instance) can dramatically reduce your monthly electrical consumption. Remember, as I’ve said many times before, efficiency is the most cost-effective means of supplying power to a home — or any building, for that matter.

And, lest you forget, the more efficient you are, the smaller your system requirements. The smaller your system requirements, the less money you’ll have to spend up front.

Assessing the Potential of a Microhydro Site

Once you have determined your family’s electrical energy demands, it is time to assess the potential of your site. You’ll need to determine how much electricity a microhydro system could produce and the percentage of your needs that it could meet. Before you do this, you should be aware of the difference between continuous power and daily power production and use.

Unlike other renewable energy systems, microhydro systems can produce electricity 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year. A system, for instance, might produce 200 watts of continuous power day in and day out. So, over a 24-hour period, this system would produce 4,800 watts-hours, or 4.8 kWh. To determine monthly output, multiply the daily output by 30. That would give you 144,000 watt-hours per month (144 kilowatt-hours). If the monthly electrical energy production of the system matches your household need, you’ll be in fine shape. However, most conventional homes — homes that don’t practice energy conservation — consume 25 kWh per day, or a little over 750 kWh per month. So, the system we are looking at would fall short of most families’ needs. If you are powering a home that is connected to the grid, use the annual electrical energy consumption to size your system. If you are powering an off-grid home, you’ll need to determine the month with the highest electrical demand, and size the system so that it meets that demand — or find some other way to supplement production, such as PVs or a small wind-electric system.

Although a microhydro system produces a fair amount of energy over a 24-hour period, what happens if your demand exceeds its output at any one time? For example, suppose your system produces 200 watts of continuous power. Although that may be enough in a given day to meet all of your household needs, what happens if you need 1,000 watts of power to run a microwave, 100 watts of power to run some lights and your computer, and 50 watts to run the television — all at the same time? And what happens when your washing machine or a power tool is turned on? As described in Chapter 8, power tools and household appliances such as dishwashers and washing machines require more power to start than to run — quite a lot more. This is known as surge power.

As Scott Davis points out in Microhydro: Clean Power from Water, “It is entirely possible to have a system that has plenty of kilowatt-hours available, but not enough capacity to start critical loads” or to meet demands that exceed continuous power output.

Demand in excess of continuous power output can be met by grid power or battery backup. In a grid-connected system, for instance, additional electrical power required to satisfy excess loads, including surge loads, is derived from the utility line connected to your home. In homes equipped with battery backup, electricity required to meet electrical demands that exceed the continuous output of the microhydro system comes from the battery bank. It is stored there during periods of excess.

Peak power demand can also be “managed away.” That is, homeowners can avoid power consumption in excess of the continuous output of a system by managing their load better — spreading out use so as not to exceed a system’s continuous power output. Peak loads can also be satisfied by using a small gas, diesel or propane electrical generator. Assessments of the site’s electrical energy production compared with household energy consumption help homeowners determine whether a site will produce enough electricity on a daily basis to meet their household needs. Understanding demand patterns, however, are also necessary. This will help homeowners decide what type of system should be installed and whether battery backup or a grid connection is needed. I will cover this in more detail shortly, but first let’s take a look at ways to assess the potential of a site.

Assessing Head and Flow

Rather than go into minute detail on the ways you determine the potential of a microhydro site, I will give you a general overview of the process. If you want to install a system, you will need more information than I could possibly supply here. You should also consult one or all of the following resources: (1) Dan New’s article in Home Power magazine, “Intro to Hydropower. Part 2: Measuring Head and Flow;” (2) Scott Davis’ book, Microhydro: Clean Power from Water; and (3) Residential Microhydro Power with Don Harris, a video produced by Scott Andrews (you can purchase a copy through Gaiam Real Goods).

When assessing the potential of a site, you need to determine two factors: head and flow. In the words of Dan New, “You simply cannot move forward without these measurements.” Your site’s head and flow will determine everything about your hydro system — pipeline size, turbine type, rotational speed, and generator size. Even rough cost estimates will be impossible until you’ve measured head and flow. New advises, “When measuring head and flow, keep in mind that accuracy is important. Inaccurate measurements can result in a hydro system designed to the wrong specs, and one that produces less electricity at a greater expense.” You may want to consult a professional with lots of experience in microhydro to help out or to make accurate measurements. If you’re lucky enough to have a local installer, it’s not a bad idea to bring him or her in on the project. It may cost you more, but you could end up with a much better system — and more energy — than if you did all of this yourself.

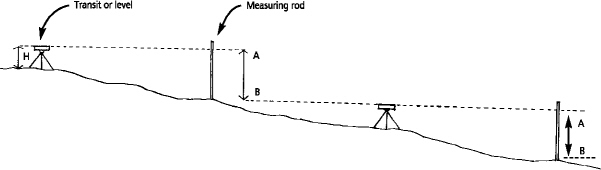

Measuring Head

Head is an engineering term for water pressure created; in the case of microhydro systems, it is created by the difference in elevation between the water intake and the turbine. Head is usually measured in feet or meters when assessing site potential. The difference in elevation between the intake and turbine can be measured by a variety of methods. For example, you can use an altimeter on a wrist watch (although cheaper ones can be off by 150 feet or more). You can also use a topographical map of your site to determine the differences in altitude between the intake and turbine.

While both of these methods work, they’re often subject to error. As Scott Davis points out, “The accuracy of the power estimate and jet sizing … requires measurement of head within 5 percent or so.” As a result, experts typically recommend direct measurement. The most accurate ways to measure vertical distances rely on some simple tools — a transit or a level (either a carpenter’s level or a hand level) and a calibrated pole, for example, an eight-foot length of pole, marked off in feet and inches. You can even get by with a level and two people. One method is shown in Figure 10-5.

Fig. 10-5: Head is the vertical drop between the intake and turbine. It is measured in a number of ways. This drawing shows one convenient method for measuring head.

Rather than try to explain each of the methods commonly used to measure head, I recommend that you read Dan New’s piece in Home Power magazine or check out Scott Davis’ book, mentioned earlier. They’ll walk you through the techniques. (By the way, New’s method for measuring uphill is one of the simplest you will find anywhere.) Don Harris shows the technique in his video, too. The various techniques for measuring head allow you and an assistant to work your way up or down a hill, measuring the drop (head) from one spot to another. When done, you simply add together all of the measurements for head from the water intake to the turbine to determine the total head.

Head can also be measured using garden hose or flexible tubing and a pressure meter. Dan New explains this technique, but points out that it works best for short distances — those in which a hose can be run from the proposed intake to the proposed turbine location. If the distance is greater than the hose length, you can link several hoses together, as long as the connections are water tight. Or you can move the hose from one spot to another, taking multiple measurements. The individual pressure settings are then added together to get the total head. In this case, however, head will be measured in water pressure, pounds per square inch or Newtons per square meter (with metric system meters). Read Dan New’s piece before you tackle this project, as there are ways that you can get false readings.

Adding all of the measurements you’ve carefully taken yields the true vertical distance from inlet to turbine, something that the microhydro folks call the “gross head” for a proposed site. But that’s not sufficient for calculations. You need to convert gross head to net head. Gross head is the pressure (measured in feet or meters) in the system when the water is not flowing. It is static head. It is the pressure reading you’d get if you ran a pipe from inlet to turbine, filled the pipe with water, but capped the end of the pipe so water could not flow out. If you opened the pipe and let water flow through it, you’d see a drop in pressure. That’s the net head.

What accounts for this difference?

Net head, the measurement you get when water flows through the pipe, is less than gross head because of friction. Net head is less than gross head because friction slows the flow of water through the pipe. That is to say, water flowing through the pipe loses some energy due to friction losses — water molecules interacting with the interior surface of the pipe. As a result, net head is always less than gross head.

Before you can determine the friction loss, you will need to know the pipe length and the flow rate — how much water will flow through the pipe. I explain below how flow is measured. For now, it is important to note that the larger the pipe, the less friction loss. Conversely, the smaller the pipe, the more friction loss. Net head declines substantially in smaller diameter pipe.

But that’s not all.

Friction losses also increase at higher flow rates. The faster the water flows through the pipe, the more friction. Moreover, friction losses increase in longer pipelines. Bends in a pipe also increase friction losses that decrease head.

These four factors — diameter of the pipe, flow rate, length of the pipe, and bends in the pipe — need to be considered very carefully when designing a system.

As a general rule, “a properly designed pipeline will yield a net head of 85 to 90 percent of the gross head you measured,” says New. Greater losses will result in unacceptable reductions in electrical production. But like anything, there are exceptions and nuances to be considered. As New points out, “higher losses may be acceptable for high-head sites (100 feet plus) but pipeline friction losses should be minimized for low-head sites.” While larger pipes reduce head loss resulting from friction, they cost more; so there’s often a tradeoff between cost and performance. As a general rule, you should design your system in such a way that head loss is no more than 10 to 15 percent. Before you can calculate head loss, you need to determine flow rate in your stream or river.

Measuring Flow Year Round

Stream flow can be measured in one of several ways. For best results, stream flow should be measured during different times of the year because fluctuations are common in perennial streams (those that flow year round). Even in temperate rain forests like those of the Pacific Northwest, there’s a dry season during which stream flows are diminished. In mountainous areas, like the Sierras and the Rocky Mountains, perennial streams flow year round, but stream flows peak during the spring months as a result of spring snowmelts. Flows decline dramatically in the summer, fall, and winter. So, to determine how much power a system can generate, you need to know a stream’s high-, medium-, and low-flow rates.

Flows in perennial streams can be reduced to a mere trickle, forcing homeowners to turn to other sources of electrical energy. Take the case of John Schaeffer, who founded Real Goods and the Solar Living Institute. John and his family live off-grid in northern California where they tap into the power of flowing water in a stream on their beautiful property. In this region of the country, rain is plentiful in the winter, but declines dramatically once June rolls around. As a result, the stream on the Schaeffer’s property pretty much dries up in the summer and stays dry until late fall. (I know, I’ve seen it!) As a result, he and his family get much of their electricity from their microhydro power system during the late fall and winter and early spring when it is quite rainy. During the summer and early fall, their PV system makes up the difference, supplying virtually all of the electricity they need. So, remember to measure flow rates, if you can, during the spring, summer, winter, and fall for the most accurate assessment of a site. Remember, too, that in climates where freezing occurs, water continues to flow in streams under the protection of a layer of ice and snow. You can tap into this energy source even though the stream appears to be frozen over for the winter. It’s wise, however — and environmentally responsible — not to take all of the water from the stream then or any time of the year!

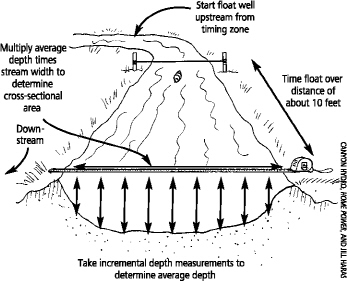

Measuring Flow Rates

Stream flow can be measured by one of three methods. The simplest is the container fill method (Figure 10-6). This is particularly useful in really narrow streams. It requires a large bucket and a stop watch. To make a measurement, you simply find a narrow spot in the waterway where you can fill a single bucket. A bucket is then thrust into the spot and filled by one person. Someone else uses a stopwatch to time how long it takes the bucket to fill. If the five-gallon bucket fills in 15 seconds, you would multiply five gallons by four to determine the amount of flow in a minute. In this instance, the flow rate would be 20 gallons per minute.

The second method is the float method, well described in Dan New’s piece in Home Power. This technique is useful for larger streams but in order to do use it, you will need to locate a fairly straight section of stream — one that’s about ten feet long, as shown in Figure 10-7. In the float method, you first measure how long it takes for a floating object to travel ten feet. Let’s say the object — a tennis ball, for instance — covers the ten feet in five seconds. This figure will then be used to calculate flow. But before you can do so, you need to know the average depth across a section of the stream, as shown in Figure 10-7. Depth measurements are taken every foot across a section of the river. The measurements are all added together, then divided by the number of measurements, yielding average depth. This figure is then multiplied by the width of the stream. If the stream is 6 feet wide and the average depth measurement is 1.5 feet, the cross-sectional area is 9 square feet. If the floating object takes 5 seconds to travel 10 feet, the stream is flowing at 2 feet per second or 120 feet per minute (2 feet per second x 60 seconds per minute = 120 feet per minute). If the cross-sectional area is 9 square feet, you simply multiply 120 feet per minute by 9 square feet and the result is 1,080 cubic feet per minute. That’s the rate of flow. (This needs to be adjusted to take into account frictional losses along the bottom of the stream.) Multiplying 1,080 cubic feet per minute by 0.83 yields the actual flow.

Fig. 10-6: The container fill method is one way to determine flow rates in small streams.

Fig. 10-7: The float method, described in the text, is another way of determining flow rates of streams and rivers.

The next method, known as the weir method, is even more involved, but it’s the most accurate of the techniques. This method requires the construction of a temporary dam across the river. Because this technique is more complicated, and involves reference to a weir table, I’ll let those interested in learning more about the method read Dan New’s account in Home Power, Issue 104. Basically, what you need to know is that to calculate the flow, you simply measure water level in a rectangular opening in the weir. You then refer to the weir table that provides data on flow in cubic feet per minute. You multiply this figure by the width of the opening, and you’re done.

Protecting the Environment

Once you have determined flow rate, you need to determine how much water can be removed from the stream without disrupting the aquatic ecosystem. Obviously, the less water that’s removed, the less impact you’ll have. To make an assessment will require more training than most readers possess. I recommend that you consult an aquatic biologist for a site assessment and recommendations. Your state division of wildlife may be able to help you out. Local permitting agencies may also have guidelines or may supply personnel. A professional stream biologist may be able to give you the best information about the potential impact of damming up part of the river and/or removing water from the stream. Renewable energy is clean and great for the environment, but you don’t want to trash your stream to produce clean power. So be careful, and show respect for the natural world that gives so much to us.

What’s the Next Step?

After determining head and water flow, you need to measure the length of pipeline. You can measure the length by pacing off the distance from the inlet to the turbine; however, it is best to measure it directly, using a 100-foot tape measure. You’ll also need to measure the distance from the turbine to your house and the battery bank. As in other renewable energy systems that produce DC power, it is best to keep the batteries as close as possible to the source of electricity (in this case, the turbine). Low-voltage DC electricity doesn’t travel well, and longer distances require larger diameter wire that is much more expensive than standard 12-gauge electrical wire. This is one reason why it is a good idea to install an AC generator in a microhydro system. The higher voltage AC travels long distances with low losses. It is also wise to keep the batteries warm year round. Lead acid batteries, the type most commonly used in these and other renewable energy systems, perform optimally at temperatures of around 70°F (21°C). (For more on batteries, see Chapter 8.)

With this information, you can begin to design a system. You’ll need to pick out a turbine that suits your purpose, and then determine pipe size. You can make these determinations yourself, or you can contact a local supplier. National suppliers of microhydro equipment, such as Gaiam Real Goods, can also lend a hand. Their staff can assist you in sizing and designing a system. They’ll provide a worksheet that asks for data that is used to generate a design for your system via a computer-sizing program. Their computer program allows them to size plumbing and wiring that will provide the least power loss at the lowest cost.

The best way for a home hydro builder to design a system “is to solicit proposals from equipment suppliers,” recommends Dan New. “Suppliers and manufacturers have been designing systems and handling problems for years, and that experience is available and free to the home developer.”

Once the system is designed, suppliers can calculate how much electrical power the proposed system will generate.

BUYING AND INSTALLING A SYSTEM

If you are designing a system on your own, you’ll need to consider each component of the system separately, starting with the intake structure. This section will help you understand a bit more about each component. If you are relying on a microhydro expert to design your system, he or she will specify the components and suggest the best design. Nonetheless, it is wise to read the material in this section so that you better understand what they’re up to. The more informed you are, the more likely you are to get the system that you will be happy with over the long haul.

A Good Site

The key element for a good site is the vertical distance the water drops. A small amount of water dropping a large distance will produce as much energy as a large amount of water dropping a small distance. Thus, we can get approximately the same power output by running 1,000 gallons per minute through a 2-foot drop as by running 2 gallons per minute through a 1,000-foot drop.

— John Schaeffer, Solar Living Source Book

As you read the following material, remember that microhydro can be combined with any other renewable energy technology. For example, a system can combine PVs and microhydro, or a wind turbine and microhydro, or perhaps all three. Microhydro systems can even be coupled with grid power or a diesel or propane generator. Combining systems not only ensures better year-round service, it also may save you some money on one or more parts of your system. For example, combining PV and microhydro will probably mean that you’ll need a smaller PV system and a smaller battery bank. With this in mind, let’s look at the various components of a microhydro system, beginning with the intake structure.

Water Intake

All microhydro systems require an intake at the highest point in the system to divert water from the stream into the penstock. As noted earlier, all intakes need to be screened to prevent debris from entering the pipeline. Ideally, the screen should be self-cleansing. In other words, it should be designed so that debris washes off naturally. Otherwise, you’ll have to manually remove debris blocking water flow into the pipeline — and do so regularly. Blockages can seriously reduce a system’s output.

Screens are immersed in water 24 hours a day, so they should be made of a durable material that won’t rust. One excellent choice is stainless steel. You can find stainless steel screens at agricultural supply outlets in rural areas where irrigation is common. If your agricultural supply outlet doesn’t have screens, they may be able to order one for you. You may also want to check out commercially manufactured microhydro intake screens like those made by Hydroscreen (hydroscreen.com).

Intake structures vary in complexity. The simplest of all intakes is a screened pipe placed in a deep pool of water in the stream. The most complex intake systems consist of small concrete diversion structures or dams that block flow across an entire stream or river. The design, of course, depends on your site.

When designing an intake, it is important to remember the function of this structure. One important function of an intake structure is to prevent air from entering the pipeline. Air flowing through a turbine reduces power output and may damage the turbine. To be sure that no air enters the system, the intake pipe needs to be fully submersed all year long. This is done by placing the pipe in a deep pool, or building an intake structure that provides a pool that is deep enough all year round to prevent air from being sucked into the system — even during that part of the year when stream flows are at their lowest.

The intake structure also needs to provide a stilling (settling) basin — a pool that allows silt, sand, gravel, and rocks to settle out before stream water enters the penstock. Figure 10-4 shows a section through an intake structure. In this structure, the stilling basin empties into a second pool. Water flows from here into the pipeline. A screen over the pipe helps prevent debris from entering it.

Microhydro systems require very little maintenance. Sealed bearings in brushless generators and long-lasting runners mean that you won’t be lubricating or replacing parts very often. You will, however, need to pay attention to the stilling basin and screen. Stilling basins may need to be emptied of debris, and screens may need to be cleaned regularly. To reduce routine cleaning, you should consider creating an overflow in the stilling pond that naturally siphons off floating debris and returns it to the stream. The screen should be as close to vertical as possible or slanted so that it self-cleans as much as possible. The intake screen and pipe also need to be submerged below the frost line to prevent freezing. Ice buildup on the screen could slow the flow of water into your system and sharply reduce its electrical output.

Choosing a Turbine/Generator

Several different types of microhydro turbine/generators are available. Your choice of turbine depends on the characteristics of your site. For mountainous sites that have fairly high pressure resulting from a favorable combination of head and water flow, you may want to consider the small Pelton wheel Harris systems (Figure 10-8). Pelton wheels are durable and require very infrequent replacement due to wear and tear. Even with dirty, gritty water, it takes at least ten years to wear out a Pelton wheel manufactured by Don Harris, according to Gaiam Real Goods. However, Harris offers a conventional automotive alternator with his system. These devices have bearings and brushes that need to be replaced at intervals of one to five years, depending on how hard the system works. To minimize maintenance, Harris also offers a brushless permanent magnet generator. These units cost about $700 more, but use larger, more sturdy bearings that last two to three times longer. This greatly reduces maintenance and replacement costs. It is well worth the extra cost.

Fig. 10-8: Harris turbine.

Harris turbines are for applications with 50 feet or more of head. They produce from 1 kWh to 35 kWh per day, depending on the model and site. The unit (generator) has an instantaneous output of about 2,500 watts — enough to start most appliances and power tools. Harris microhydro turbines come in 24- and 48-volt models and are manufactured in the United States.

Fig. 10-9: Low Head Stream Engine.

Fig. 10-10: Jack Rabbit.

For low-head systems that channel a lot of water through a turbine with little head (that is, on flatter sites), you may want to consider a Low Head Stream Engine (Figure 10-9) or one of the newest microhydro turbine/generators, the Jack Rabbit (Figure 10-10). The Stream Engine is a brushless permanent magnet generator with sealed bearings that minimize maintenance. These units operate in sites with heads that range from 5 to 400 feet that have flow rates from 5 to 300 gallons per minute (although flow rates above 150 gpm provide very little additional power). Although set-up can be a bit tricky, the unit is virtually maintenance-free. Output voltages are 12, 24, and 48 volts. They’re manufactured in Canada.

The Jack Rabbit is an unusual microhydro turbine and generator. As shown in Figure 10-10, this submarine-like device consists of a submersible propeller and generator in a waterproof casing that’s suspended in a stream in at least 13 inches of water. The generator operates at low speeds, ideally around 9 miles per hour, or equivalent to a slow jog. Water flowing past the device causes the propeller to spin.

In slow-moving streams, water flows can be increased by piling rocks or heavy timbers to create a funnel with the wide end facing upstream. This channels water into the narrow end of the funnel, which greatly increases its speed. (This phenomenon is known as the Venturi effect.) The Jack Rabbit is placed at the narrow part of the funnel where the water is flowing most rapidly, optimizing the performance of the generator.

Jack Rabbits are low-capacity microhydro turbines that produce 100 watts of continuous power in a 9-mile-per-hour stream — or about 2.4 kWh of electricity per day — and slightly less in a slower stream. Jack Rabbits are rugged and require very little maintenance. The heavy-duty aluminum blades are not easily damaged. If struck by a log and bent, the propeller blades can be hammered back into shape. Another advantage of the Jack Rabbit is that it requires no pipeline, a feature that can save you a lot of money. Electrical lines from the generators (mounted securely in a stream) carry the current to the house. Jack Rabbits come in 12- and 24-volt models and are made in Great Britain. Proceed with caution with these, however. Word from users is that the power output is very low, and there are other problems that may make them a dubious choice.

Finally, the Low Head Stream Engine, with a turbo-type runner, is for use in sites that offer intermediate characteristics. They operate in areas with drops of 2 to 10 feet and flows ranging from 200 to 1,000 gallons per minute. Peak output is 1,000 watts, meaning that a turbine operating in a good site will provide 24 kWh of electricity per day.

To learn more about these systems, I strongly recommend that you consult John Schaeffer’s book, Solar Living Source Book. It provides a good overview of the subject and a lot of valuable information on the various microhydro turbines, including pricing. Remember, as Dan New points out, that “the turbine should be designed to match your specific head and flow. Proper selection requires considerable expertise.”

AC Generators

Although most microhydro systems produce DC electricity, there are some times when AC generators are advisable, notably for larger commercial applications or for grid-connected systems. These systems can produce more than 3,000 watts of continuous power or 72 kWh per day — far more than most homes ever consume. As Dan New pointed out in an e-mail to me, these systems “can often supply all of the energy needs of a home.” DC systems typically only provide electricity for lighting, appliances, and electronic heaters, but not space heat, hot water, or dryers. Those demands are typically satisfied by propane or natural gas. An AC microhydro system, however, could supply heavy-duty machines, compressors, and welding and woodworking equipment. “Most DC systems cannot cover most of this list,” concludes New, so homeowners must rely “on nonrenewable sources of energy to accomplish these tasks.”

According to Schaeffer, AC systems often involve considerable engineering, custom metalwork, formed concrete, permits, and a fairly high initial investment. AC systems also require governors to ensure that the AC generator spins at the correct speed to produce electricity of the proper frequency to match household needs. In grid-connected systems, additional controls are required to ensure that power going onto the electric grid matches line current with respect to voltage, frequency, and phase. These controls will automatically disconnect the system from the grid if major fluctuations occur on either end. Although AC systems cost more upfront, “AC power is almost always cheaper per kilowatt-hour,” says New. AC hydro systems also require no batteries and do not require inverters. AC power is used directly as it is produced. Surplus can be diverted to dump loads, usually resistance heaters, or can be diverted to the electrical grid. “So,” says New, “if a homeowner can find a use for most of the power most of the time, a moderately sized AC system, say 4 kW to 15 kW, will provide the energy needed to power a home renewably for less money.” (For details on grid-connected renewable energy systems, see Chapter 8.)

For those who want battery backup, in case the system must be shut down, remember that AC power can be converted to DC power by a bank of diodes and then stored in a battery bank for later use. However, also remember that to be useful, DC electricity from the battery bank must be converted back to AC power. That’s a function of the inverter. As Dan New pointed out to me, systems that convert AC to DC power are rare.

AC systems can be quite costly, warns Schaeffer, so this “isn’t an undertaking for the faint-of-heart or thin-of-wallet.” This is not to say these systems are uneconomical. Quite the opposite: they often provide a very good return on investment. “Far more streams can support a small DC-output system,” says New, “than a higher output AC system.” Those who think they have a site that is suitable for low-head AC power production, can download information on these systems from the following website: eere.energy.gov/RE/hydropower.html. For more on the cost issue, see the sidebar, “AC vs DC Costs.”

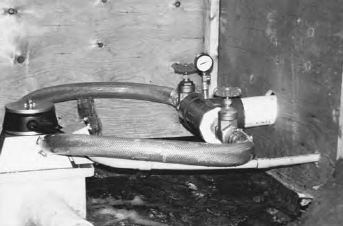

Powerhouse

As noted earlier, turbines and generators must be protected from the elements to ensure long service. Protection is provided by a powerhouse. Powerhouses range in complexity from simple wooden or cement block boxes (designed so you can work on the system) to small sheds with room for battery banks.

Be sure when connecting pipes to the turbine in a powerhouse to use as few elbows as possible. Bends in pipe dramatically reduce head by creating turbulence. Reduced head, in turn, reduces system output. “Likewise,” notes Dan New, “any restrictions on water exiting the turbine may increase resistance against the turbine’s moving parts.” This, too, reduces power output.

AC vs DC Costs

Although an AC microhydro system typically costs more than a DC system, this comparison isn’t fair. You’re not comparing apples to apples. Most DC systems don’t produce anywhere near as much electricity as AC systems. The result is that you will very likely need to acquire additional energy to run your home, for example, natural gas. You may also need to install additional equipment, for example, a wood stove to provide heat or a gas or diesel generator to provide additional electricity to run a washing machine.

Drive Systems

In most systems, a steel shaft connects the turbine to the generator. This shaft couples the turbine with the generator so that rotation of the turbine’s runner translates into rotation within the generator. “The most efficient and reliable drive system involves a direct 1:1 coupling between the turbine and generator,” notes New. But this is not possible for all sites. In some cases, especially when AC generators are used, it may be necessary to “adjust the transfer ratio so that both the turbine and generator run at their optimum (but different) speeds,” he adds. This is achieved through gears, chains, or belts. Belt systems are the most popular because they are the least expensive. Unfortunately, more complex drive systems increase the cost of a system and will invariably increase maintenance requirements.

Batteries

For those who need lots of power intermittently (which is most of us) a battery system or a grid-connected system may be advisable.

Most microhydro systems use deep-cycle lead acid batteries. Never, never, never use automobile batteries. They can’t handle the deep discharging. Batteries for renewable energy systems were covered at length in Chapter 8, but I’ll point out one important fact here. As a general rule, microhydro systems require much smaller, and thus much less expensive, battery banks than solar electric or wind electric systems. That’s because these systems only need to provide electricity for occasional heavy power usages and power surges. You’re not trying to store power for three to four days of cloudy weather, as in the case of a PV system, or windless days, in the case of a wind energy system. The battery bank is also smaller because of rapid recharge. That is, if the batteries are drawn down during the day, they’re usually recharged by evening. Occasional high output and rapid recharge not only means fewer batteries, it also means a longer battery life, for reasons explained in Chapter 8.

Pipeline

After designing an intake structure and selecting a turbine, you’ll need to design a pipeline. Pipelines are typically made from either 4-inch PVC or smaller polyethylene pipe. PVC is used almost exclusively when the pipe needs to be over 2 inches in diameter, although 1.5- to 2-inch PVC can be and is used. Four-inch PVC pipe comes in 10- and 20-foot sections that are glued together. Assembly is quick and painless and can be mastered by anyone. PVC pipe not only goes together easily, it is relatively inexpensive. In addition, PVC pipe is very light, so it is easy to install, which is especially helpful in steep terrain. Two-inch polyethylene pipe is used for smaller flows. It comes in very long rolls that are laid out from intake to turbine. Because there’s no gluing (unless two rolls must be connected), polyethylene pipe goes in much faster than PVC.

Although plastic pipe is fairly inexpensive, the pipeline can be a costly and time-consuming aspect of a microhydro system. “It’s not unusual to use several thousand feet of pipe to collect a hundred feet of head,” notes Schaeffer. Additionally, in cold climates, pipe may need to be buried below the frost line to prevent it from freezing. This can add significantly to the cost and labor required to install a system, especially if the soils are rocky and difficult to work in, which is often the case in mountainous terrain. However, Scott Davis points out that “even if the pipe is not quite below the frost line, water running through the pipe may keep it from freezing.”

Burying the pipeline not only protects the pipe from freezing, it helps protect it from damage, for instance, from falling trees or tree limbs. And it helps keep the pipe from shifting around as high-pressure water flows through it. PVC pipe deteriorates in sunlight, too, necessitating burial.

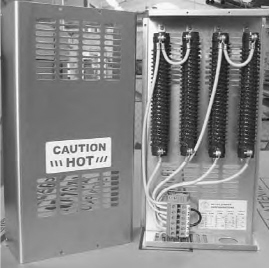

Controllers

Microhydro systems require special controllers to prevent batteries from overcharging, and hence from being permanently damaged. Unlike the charge controllers on PV systems that terminate the flow of electricity to the batteries, microhydro system controllers shunt excess electricity to a secondary load, typically an electric resistor or two (Figure 10-11). These resistors are typically water- or space-heating elements that put excess electricity to good use heating domestic hot water or the house. They are referred to as dump loads. (Note: PV charge controllers should not be used in a microhydro system, as they could damage the generator.)

Excess power is shunted to secondary loads in off-grid systems when the system’s batteries, if any, are full and when the household demands are being met by the system. In grid-connected systems, excess power is diverted onto the grid.

Load controllers and water heater and air heater diversion devices can be purchased from Gaiam Real Goods and other suppliers that cater to folks interested in microhydro.

Power Lines

Most microhydro systems produce low-voltage DC electricity that travels in a wire to the battery bank. Because low-voltage current doesn’t travel well — it loses energy quickly over distance — it is best to keep power lines from the turbine/generator short, under 100 feet. If this is not possible, you will need to use large-gauge wire, which costs much more than standard wire.

Fig. 10-11: Load diverters (dump loads) take excess energy and run it through resistors (shown on the right) to generate heat. They’re useful in the winter to provide heat to living spaces as well as garages, sheds, and workshops.

Permitting

Jeffe Aronson installed a low-head microhydro system on a stream running through his property in Australia. He did so by building a small concrete dam across part of the river. Although friends recommended that he complete the project without permits and “let the bureaucrats find it if they could,” Jeffe decided to secure the necessary permits and work with local authorities. In fact, he made a point of working with them in a cooperative fashion — and not showing anger or frustration at some of their quirks. In short, he established a good, respectful working relationship. “A couple years later,” Aronson writes in Home Power, Issue 101, a visiting angler, “who had fished this section of river for decades and considered it his own, came upon our works.” The angler was outraged and, rather than consult Jeffe, he sent a complaint to the water catchment authority. “They sent a representative with whom we’d dealt originally,” said Aronson. “He thankfully found that we’d done what we’d said we’d do and even felt the works to be ‘very discreet.’” And that was the end of the story. The lesson in this tale is that permitting may be a bother, but it can save you a lot of hassle and expense. In fact, government agencies can force a landowner to remove a system that cost several thousand dollars to install, if they catch him or her generating microhydro without a permit.

Ask a local supplier or installer to find out what permits are required. If there are no local experts, you will need to call the state’s office of environmental protection or state energy office. They can steer you in the right direction.

FINDING AN INSTALLER OR INSTALLING A SYSTEM YOURSELF

Microhydro systems are pretty easy to install. In fact, people with modest plumbing and electrical skills can install most of a system without much trouble. However, battery banks, inverters, and other controls typically used in off-grid systems require a higher degree of expertise than many do-it-yourselfers possess. Grid-connected systems require a high level of electrical expertise too. My advice is that it’s always a good idea to hire a professional to help you out or to do the job for you. Experienced professionals know the tricks of the trade and can save you a lot of time, trouble, expense, and frustration. I’ve always been amazed when working with experts on wind and solar systems, for instance, how little tricks of the trade make the job go so much easier!

A professional installation will cost more, but the added expense could very likely be well worth it. Not only will you probably get a better system, you’ll have someone to call in case something goes wrong and you can’t fix it.

To locate a professional, contact a local renewable energy society or, if there is none, call a manufacturer or Real Goods and ask for references in your area.

THE PROS AND CONS OF MICROHYDRO SYSTEMS

Microhydro is a great source of reliable electrical energy, but before you go out to buy a system, you should have a full understanding of its pros and cons. On the plus side, microhydro is probably the most cost-effective renewable energy system on the market. According to Scott Davis, it delivers “the best bang per buck.” Davis goes on to say, “Significant power can be generated with flows of two gallons per minute or from drops as small as two feet.” And, says Davis, “power can be delivered in a cost-effective fashion a mile or more from where it is generated to where it is being used.”

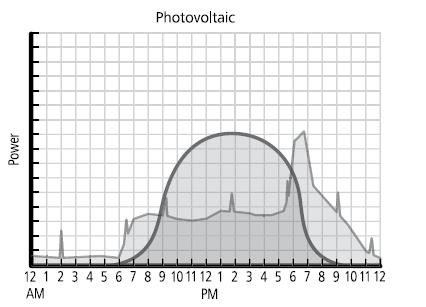

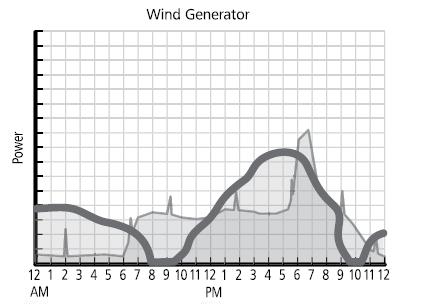

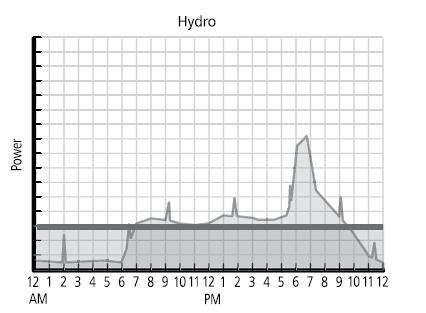

Microhydro, unlike almost all other renewable forms of energy (certainly wind and solar) often provides continuous power. That is to say, it provides electricity day and night, night and day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year. Excess power can be stored in batteries or can be fed onto the utility grid, if it’s nearby. As Figure 10-12 shows, microhydro can do a much better job of meeting one’s needs. Solar and wind systems require either considerable storage capacity or a connection to the electrical grid to supply continuous power. Microhydro sites owe their year-round performance in part to the fact that they can be easily winterized. Even though stream flows may slow down during the winter in snowy climates, small streams continue to offer reliable water flows because moving water doesn’t freeze very readily. Burying pipes underground below the frost line also helps to ensure a steady flow. Furthermore, notes Davis, microhydro can be integrated with pipelines delivering water to a house from a spring or stream located uphill from the building. small microhydro systems are inexpensive, too, costing from $2,000 to $10,000.

Your electrical needs vary over time.

PV outputs drop to zero every night and are much reduced in winter and cloudy weather.

Wind system outputs go up and down irregularly.

Microhydro systems have the same output all the time.

Fig. 10-12: Comparison of microhydro and hybrid solar/wind systems.

DRAWINGS BY CORRI LOSCHUCK MICROHYDRO: CLEAN POWER FROM WATER

Yet another advantage of microhydro is that it is applicable to a variety of different conditions — from high head/low flow to low head/high flow and everything in between. The rule of thumb is, the more head, the less volume will be necessary to produce a given amount of power. The less head, the more volume you’ll need.

Like all systems, there are some disadvantages to microhydro systems. First off, very few suitable sites are available, say, in comparison to solar electric or wind energy sites. Second, microhydro systems require considerable knowledge. Third, not all sites that could be used for microhydro can be developed economically. Pipelines for a system, for instance, may be long and thus costly. Or they may be difficult to install. Fourth, diverting water from streams can alter flows and adversely affect living organisms that rely on the water. You need to exert extreme caution when installing a microhydro system. Be sure to consult with a qualified stream biologist. Fifth, microhydro systems may require permits from local government agencies, which can take time and may require a financial outlay on your part — notably, for engineering costs or the costs of a biologist to examine the site for potential impact. In British Columbia, one of my clients had two large streams flowing on either side of his property but could not tap into the flowing water because the province prohibits structures on streams to protect fish populations.

As with any system, you need to proceed carefully and cautiously — with as complete an understanding of the system as possible. If you are lucky enough to live by a stream or river and can legally tap into the power of the water running by your home, you could be graced with years of very inexpensive, clean, and renewable energy.