Nicholas and his wife, Erika, like to joke that they had an arranged marriage, South Asia style. Though they lived within four blocks of each other for two years and were both students at Harvard, their paths never crossed. Erika had to go all the way to Bangladesh so that Nicholas could find her. In the summer of 1987, he went to Washington, DC, where he had grown up and gone to high school, to care for his ailing mother. He was a medical student, single, and, he foolishly thought, not ready for a serious relationship. His old high-school friend, Nasi, was also home for the summer. Nasi’s girlfriend, Bemy, who had come to know Nicholas well enough that her gentle teasing was a source of amusement for all of them, was also there. She had, as it turned out, just returned from a year in rural Bangladesh, doing community development work.

In the waterlogged village where Bemy had spent her year abroad was a beautiful young American woman with whom she shared a burning desire to end poverty and a metal bucket to wash her hair. You probably know where this story is going. One afternoon, in the middle of the monsoon, while writing a postcard to Nasi, Bemy suddenly turned to her friend Erika and blurted out: “I just thought of the man you’re going to marry.” That man was Nicholas. Erika was incredulous. But months later, she agreed to meet him in DC, when the four of them had dinner at Nasi’s house. Nicholas was of course immediately smitten. Erika was “not unimpressed,” as she later put it. That night, after getting home, Erika woke up her sister to announce that she had, indeed, met the man she was going to marry. Three dates later, Nicholas told Erika he was in love. And that is how he came to marry a woman who was three degrees removed from him all along, who had practically lived next door, who had never known him before but who was just perfect for him.

Such stories—with varying degrees of complexity and romance—occur all the time in our society. In fact, a simple Google search for “how I met my wife” and “how I met my husband” turns up thousands of narratives, lovingly preserved on the Internet. They can be short, such as this one: “How did I meet my husband? At a bar. He was a friend of the scummy boyfriend, soon-to-be-husband of my best friend (yes, they’re divorced). I was introduced to him in a bar… hooked up… and we’re still together, and married… while my best friend isn’t!”

Or the stories can be more involved: “I drove into the valley of Yosemite National Park sometime after the sun went down with my two girlfriends and a pitbull. I had worked there the two summers before and was preparing for another season. When we stepped out of the car, it was freezing, and we had to trudge through a foot of snow up to our friend’s cabin. He wasn’t home but had left a note directing us to another cabin. We were wet up to our calves by the time we reached it, and I felt uncomfortable knocking on a stranger’s door. Luckily, our friend opened up and invited us in to his friend’s cabin. He made introductions, and I must’ve seemed rude because I ran to the heater and turned my back to the room. Somehow, the occupancy level diminished without me realizing it, and I ended up sitting on a bed opposite my future husband. He reminded me of a young Dave Matthews. His southern accent was charming, and those eyes… God, those eyes. We talked well into the night until my friend, who had settled into a bed near me, sighed and begged for us to leave. I thanked him for having us, and he said, ‘Well, now you know where I live so drop in anytime.’ Back in the cold Sierra night, we giggled all the way down to the parking lot where I turned to my girlfriends and said those fateful words, ‘I’m going to marry that man!’ Two years and five months later, I did.”1

The romantic essence of these stories is that they seem to involve both luck and destiny. But, if you think about it, these meetings aren’t so chancy. What these stories really have in common is that the future partners started out with two or three degrees of separation between them before the gap was inexorably closed.

The romantic ideal of finding a partner often also involves the sense that you have the right “chemistry” with your intended or that the two of you fall in love for mysterious, inexplicable reasons. We think of falling in love as something deeply personal and hard to explain. Indeed, most Americans believe that their choice of a partner is really no one else’s business. Some people select their partners impulsively and spontaneously; others quite deliberately. Either way, partner choice is typically seen as a personal decision. This view of relationships is consistent with our general tendency to see major life decisions as individual choices. We like to believe that we are at the helm of our ship, charting an entirely new course, no matter how choppy the seas. It’s surprising and maybe even disappointing to discover that we are in fact sailing through well-traveled shipping lanes using universal navigational tools.

Because we are so sure of our individual power to make decisions, we lose sight of the extraordinary degree to which our choice of a partner is determined by our surroundings and, in particular, by our social network. This also helps to explain the romantic appeal of stories involving putatively chance encounters, for they seem to suggest that forces larger than ourselves are at work, and that romance with a particular, unknown person is predestined and magical. Now, we are not suggesting there isn’t something amazing about meeting the love of your life after trudging through the snow at Yosemite or washing your hair in a bucket in Bangladesh. It’s just that those magical moments are not as random as we might think.

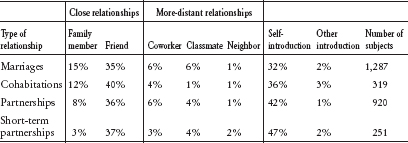

Consider some systematic data about how people meet their partners. The National Survey of Health and Social Life, also quaintly known as the Chicago Sex Survey, studied a national sample of 3,432 people aged eighteen to fifty-nine in 1992 and provides one of the most complete and accurate descriptions of romantic and sexual behavior in the United States.2 It contains detailed information about partner choice, sexual practices, psychological traits, health measures, and so on. It also includes a type of data that is surprisingly very rare, namely, how and where people actually met their current sexual partners. The table shows who introduced couples in different kinds of relationships.

Who introduced the couple?

Note: Numbers do not add to 100 percent because of rounding.

The introducers here did not necessarily intend for the two people they introduced to become partners, but the introduction nevertheless had this effect. Roughly 68 percent of the people in the study met their spouses after being introduced by someone they knew, while only 32 percent met via “self-introduction.” Even for short-term sexual partners like one-night stands, 53 percent were introduced by someone else. So while chance encounters between strangers do happen, and while people sometimes find their partners without assistance, the majority of people find spouses and partners by meeting friends of friends and other people to whom they are loosely connected.

While friends were a source of introduction for all kinds of sexual partnerships at roughly the same rate (35–40%), family members were much more likely to introduce people to their future spouses than to future one-night stands. And how people meet is also relevant to how quickly they have sex. In the Chicago study, those who met their partners through their friends were slightly more likely to have sex within a month of meeting than those who met through family members. A similar study conducted in France found that couples who met at a nightclub were much more likely to have sex within a month (45 percent) than those who met at, say, a family gathering (24 percent), which is not surprising since one typically does not have sex in mind at family events.3

These data suggest that people might use different strategies to find partners for different kinds of relationships. Maybe people ask family members for introductions to possible marriage partners and rely on their own resources to meet short-term partners. This makes intuitive sense: most drunken college students are not texting their mothers to see if they should invite that cute stranger at the bar home for the night. So, what you get when searching your network depends in part on where you are looking and what you are looking for.

However, it is clear that people rely heavily on friends and family for all kinds of relationships. When you meet a new person on your own, you only have information about yourself. In contrast, when others introduce you to someone new, they have information about both you and your potential partner, and sometimes they play the role of matchmaker (consciously or not) by encouraging meetings between people they think will get along. Friends and family are likely to know your personalities, social backgrounds, and job histories, and they also know important details such as your tendency to leave underwear on the floor or to send roses. The socially brokered introduction is less risky and more informative than going it alone, which is one reason people have relied on introductions for thousands of years.

Yet in most modern societies, we generally have a negative view of arranged marriages, and we cannot possibly imagine what it would be like to marry a stranger. Well-meaning friends and relatives who nosily interfere in our lives to help us find partners are seen as comic figures, like Yente in Fiddler on the Roof. But, in fact, our friends, relatives, and coworkers typically take on a matchmaking role only when they think we are having trouble finding a partner on our own. And as it turns out, our social network functions quite efficiently as matchmaker, even when we insist we are acting out our own private destiny.

The structure of naturally occurring social networks is perfectly suited to generate lots of leads. In networks such as bucket brigades and phone trees, there are only a limited number of people within a few degrees of separation from any one person. But in most natural social networks, there are thousands. As we discussed in chapter 1, if you know twenty people (well enough that they would invite you to a party), and each of them knows twenty other people, and so on, then you are connected to eight thousand people who are three degrees away. If you are single, one of all these people is likely to be your future spouse.

Of course, random encounters can sometimes bring strangers together, especially when incidental physical contact is involved. These happy accidents are frequently used as plot devices in romantic stories, whether it’s two people grabbing the same pair of gloves in Serendipity, an umbrella taken by mistake after a concert in Howard’s End, or dogs getting their leashes entangled in 101 Dalmatians. Incidents like these provide opportunities for further social interaction, and possibly sex or marriage, because they require what sociologist Erving Goffman called “corrective” rituals: people have to undo the “damage,” and this in turn means that they have to get to know each other. Good flirts are able to turn such happenstance into real opportunities. And the best flirts may even be able to contrive an “accident” in order to meet someone: they make their own luck. But these are the exceptions more than the rule. And it is noteworthy that even these meetings of strangers involve some degree of shared interest, whether in clothing, music, or pets, for instance.

Even when people meet on their own, without help from mutual contacts, there is a social preselection process that influences the kinds of people they are likely to run into in the first place. For example, the Chicago Sex Survey also collected data on where Americans met their partners. Sixty percent of the people in the study met their spouses at places like school, work, a private party, church, or a social club—all of which tend to involve people who share characteristics. Ten percent met their spouses at a bar, through a personal ad, or at a vacation spot, where there is more diversity but still a limited range of types of people who might be available to become future spouses.4

The locations and circumstances under which people meet partners have been changing over the past century. Our best data on this come from a study conducted in France. Looking across a broad range of venues where people meet spouses, including nightclubs, parties, schools, workplaces, holiday destinations, family gatherings, or simply “in the neighborhood,” the investigators traced the change across time. For example, from 1914 until 1960, 15 to 20 percent of people reported meeting their future spouses in the neighborhood, but by 1984 this percentage was down to 3 percent, reflecting the decline of geographically based social ties as a consequence of modernity and urbanization.5

Geography is even less important with the rise of the Internet. In 2006, one in nine American Internet-using adults—all told, about sixteen million people—reported using an online dating website or other site (such as Match.com, eHarmony.com, or the wonderfully named PlentyofFish.com, as well as countless others) to meet people.6 Of these “online daters,” 43 percent—or nearly seven million adults—have gone on actual, real-life dates with people they met online, and 17 percent of them—nearly three million adults—have entered long-term relationships or married their online dating partners, according to a systematic national survey.7 Conversely, 3 percent of Internet users who are married or in long-term committed relationships reported meeting their partners online, a number that will likely rise in the coming years.8 Gone are the days of the girl next door. People increasingly meet their partners through (offline and online) social networks that are much less constrained by geography than they used to be.

With the decline in importance of meeting people in the neighborhood in recent years, people no longer search geographic space for partners. Nevertheless, they still search social space. Rather than going from house to house or town to town, we jump from person to person in search of the perfect mate. We see if anyone near us in our network (e.g., our friends, coworkers) would be a suitable partner, and if not, we look farther away (e.g., our friends’ friends, our coworkers’ siblings). And we often seek out circumstances, such as parties, that are likely to result in meeting friends of friends and people still farther away in our network.

We have “weak ties” to friends of friends and other sorts of people we do not know very well. But, as we will discuss in chapter 5, these kinds of ties can be incredibly valuable for connecting us to people we do not know at all, thereby giving us a much greater pool of people to choose from. So the best way to search your network is to look beyond your direct connections but not so far away that you no longer have anything in common with your contacts. A friend’s friend or a friend’s friend’s friend may be just the person to introduce you to your future spouse.

Some societies have richly prescriptive procedures for partner search, and although they severely limit personal choice for the betrothed, they still exploit network connections. Such marriages are often arranged for legal or economic reasons rather than from a desire to find a suitable partner (in the Western sense), and they are common in the Middle East and Asia. In some cultural settings, customs prescribe that the prospective partners be introduced to each other, and the parents take an active role in vetting the family and the potential spouse. In other settings, however, the marriage is a settled matter from the first meeting, and no courtship is allowed. Across cultures, there is considerable variation in who the matchmakers are (parents, professionals, elders, clergy), what pressures the matchmakers can exert, what qualifications the spouses must have (reputation, wealth, caste, religion), and what sanctions can be imposed if the couple refuses (disinheritance, death).

These practices are not immutable, however, even in societies where arranged marriage was formerly the norm. For example, the percentage of women living in Chengdu in Sichuan, China, who had arranged marriages shrank from 68 percent of those married between 1933 and 1948 to 2 percent of those wed between 1977 and 1987.9 Nevertheless, social-network ties still remain crucial; 74 percent of respondents in Chengdu report that the primary network that connects young people to potential mates is friends and relatives in the same age group.

Regardless of what kind of network people use, whether real or virtual, the process of searching for a mate is usually driven by homogamy, or the tendency of like to marry like (just as homophily is the tendency of like to befriend like). People search for—or, in any case, find—partners they resemble (in terms of their attributes) and partners who are of comparable “quality.” The Chicago Sex Survey, for example, shows that the great majority of marriages exhibit homogamy on virtually all measured traits, ranging from age to education to ethnicity. Other studies show that spouses usually have the same health behaviors (like eating and smoking), the same level of attractiveness, and the same basic political ideology and partisan affiliation (with rare, notable exceptions like Clinton adviser James Carville and Republican strategist Mary Matalin). We would expect more homophily in long-term relationships and less in short-term relationships (one is less finicky when it comes to sexual partners than potential spouses), and to some extent this is indeed the case: 72 percent of marriages exhibit homophily (based on a summary measure involving several traits), compared to 53 to 60 percent for other types of sexual relationships.10 In addition, as we shall see, spouses also become more similar over time because they influence each other (for example, in political affiliation, smoking behavior, or happiness).

On the one hand, homogamy makes intuitive sense. People like being around others who are similar to them. Most people find it comforting to imagine that partners resemble each other because it gives them hope that they, too, will someday be happy in a warm and loving relationship with a kindred spirit. On the other hand, think about the odds of finding someone just like you. Personal ads are full of complex laundry lists that must be very difficult, if not impossible, to satisfy: Wanted: frisky, down-to-earth, nonsmoking, leftist Democrat salsa dancer who likes guns, Bollywood films, NASCAR races, Ouija boards, beach sunsets, Cosmopolitans, country drives, and triathlons.

Indeed, the uniqueness of each human being has implications for how many people out there are a perfect fit in this sense. The age-old debate about whether you have one soul mate or a million rests in part on how picky you are. But even if there are a million compatible people for you, that is just one of every six thousand people in the whole world. If you are choosing at random, you had better go on a lot of dates. The dispiritingly unromantic conclusion is that you will never, ever find Mr. or Ms. Right. Not without some help.

But the surprising power of social networks is that they bring likes together and serve up soul mates in the same room. Bigger and broader social networks yield more options for partners, facilitate the flow of information about suitable partners via friends and friends of friends, and provide for easier (more efficient, more accurate) searching. Hence, they yield “better” partners or spouses in the end. The odds of finding that soul mate just improved substantially.

Given the structure of social networks, our tendency to be introduced to our partners, and our innate comfort with people we resemble, it is not surprising that we generally wind up meeting, having sex with, and marrying people like ourselves. The choice of a partner is constrained by the same social forces that create network ties in the first place. Who we befriend, where we go to school, where we work—all these choices largely depend on our position in a given social network. No matter where people search, their network generally acts to bring similar people together. The fact that spouses are so often similar manifestly disproves the idea that people meet and choose their partners by chance.

American satirist H. L. Mencken famously observed that wealth is “any income that is at least one hundred dollars more per year than the income of one’s wife’s sister’s husband.” With this statement, he captured an idea that is well known to most people but strangely unpopular in the formal study of economics: namely, that people often care more about their relative standing in the world than their absolute standing. People are envious. They want what others have, and they want what others want. As economist John Kenneth Galbraith argued in 1958, many consumer demands arise not from innate needs but from social pressures.11 People assess how well they are doing not so much by how much money they make or how much stuff they consume but, rather, by how much they make and consume compared to other people they know.

An essential truth in Mencken’s quip is that the two men are comparing themselves to those from whom they are three degrees removed. They do not compare themselves to strangers. Instead, they seem intent on impressing people they know. In a classic experiment investigating this phenomenon, most people reported that they would rather work at a company where their salary was $33,000 but everyone else earned $30,000 than at another, otherwise identical company where their salary was $35,000 but everyone else earned $38,000.12 Even though their absolute income is less at the first job, they think they would be happier working there than at the second. We would rather be big fish in a small pond than bigger fish in an ocean filled with whales.

Perhaps not surprisingly, this is also true of our desire to be attractive. In one creative experiment, respondents were asked which of the following two states they would rather be in:

A: Your physical attractiveness is 6; others average 4.

B: Your physical attractiveness is 8; others average 10.

Overall, 75 percent of people preferred being in situation A than in situation B. For most people, their relative attractiveness was more important than their absolute attractiveness.13 We have repeated this experiment with Harvard undergraduates, and their responses were even more skewed: 93 percent preferred situation A, and 7 percent situation B. And, of course, any bridesmaid forced to wear an unflattering dress understands this point.

These results show that our preference for relative attractiveness is more extreme than our preference for relative income. People realize how crucial it is to have sex appeal if they are to have sex. And they realize how important it is to be more attractive than their prospective mate’s other choices. In other words, relative standing is important if it has what is known as an instrumental payoff: a more appealing physique than others is a means to an end.

This preference for relative standing brings to mind another classic anecdote: Two friends are hiking in the woods and come to a river. They take off their shoes and clothes and go for a swim. As they come out of the water, they spot a hungry bear that immediately starts to run toward them. One of the men starts fleeing immediately, but the other pauses to put on his shoes. The first man screams at the second, “Why are you putting on your shoes? They won’t help you outrun the bear!” To which the second man calmly responds: “I don’t need to outrun the bear; I just need to outrun you.”

It is this same reasoning that drives ever-larger numbers of people to have plastic surgery and with greater frequency. Liposuction might yield a physical advantage for early adopters, but when everybody gets it done, the advantage goes away. As a result, people then demand other kinds of plastic surgery in a kind of silicone arms race. The breadth of services demanded explodes to parallel the spread of services through the network.

Competition for mates can actually be quite stressful. One investigation we conducted suggests that the higher the male-to-female ratio at a time when a man reaches his early twenties, the shorter his life. A man who is surrounded by other men has to work harder to find a partner, and this environment of elevated competition has long-term consequences for his health. In this regard, we are no different from a number of animal species. In one analysis, we examined the effect of the gender ratio in a sample of high-school seniors in Wisconsin in 1957—a total of 4,183 young men and 5,063 young women in 411 high schools. We found that men in high-school graduating classes with lopsided gender ratios (of more men) wound up with shorter life spans fifty years later. In another analysis of more than 7.6 million men from throughout the United States, we found that the availability of marriageable women again had a durable impact on men’s health, affecting their survival well into their later years.14

These results suggest that the people who surround us are not only a source of partners or of information about partners; they also are our chief competitors. As a result, the social network in which we find ourselves defines our prospects. It does so by defining whom we meet, by influencing our taste in what is deemed desirable in a partner, and, finally, by specifying how we are perceived by others and what competitive advantages and disadvantages we have. You don’t need to be the most beautiful or most wealthy person to get the most desirable partner; you just need to be more attractive than all the other women or men in your network. In short, the networks in which we are embedded function as reference groups, which is a social scientist’s way of saying “pond.”

In the 1950s, Robert K. Merton, a very influential social scientist, codified the basic ways that reference groups affect us: they can have comparative effects (how we or others evaluate ourselves), influence effects (the way others dictate our behaviors and attitudes), or both.15 Having unattractive social contacts may make us feel superior (comparison) but may also make us take worse care of ourselves (influence). These two effects may work at cross-purposes in our quest to find a partner.

For decades, reference groups have been seen as abstract categories: people often compare themselves to other “middle-class Americans” or other “members of their grade at school” or other “amateur soccer players.” But exciting advances in network science are now enabling us to map out exactly who these references group are for each person. Many people may be more attractive than we are, but our only real competitors are the people in our intended’s social network.

People we know influence how we think and act when it comes to sex. To begin with, both friends and strangers affect our perceptions of a prospective partner’s attractiveness, consciously and unconsciously. These effects go beyond basic tendencies that men and women have to make judgments about appearance; for example, it has repeatedly been shown that men find women with low waist-to-hip ratios more attractive, and women value certain facial features in men. Until recently, most research on partner choice and assessments of attractiveness has focused on an individual’s independent preferences. Yet there are good biological and social reasons to suppose that perceptions of attractiveness can spread from person to person.

An experiment suggests how. First, investigators took pictures of men who were rated equally attractive by a group of women.16 Then, they presented pairs of pictures of two equally attractive men to another group of women, but between each pair of pictures, they inserted a picture of a woman who was “looking” at one of the men. This woman was smiling or had a neutral facial expression. The female subjects were much more likely to judge a man to be more attractive than his competitor if the woman interposed between the photos was smiling at him than if she was not.

In another study, a group of women again rated photographs of men for attractiveness. The photos were accompanied by short descriptions, and when the men were described as “married,” women’s ratings of them went up.17 In still another study, men in photographs with attractive female “girlfriends” were judged to be more attractive when the “girlfriend” was in the photo than when she was not. Having a plain “girlfriend,” however, did not enhance a man’s appeal as much.18 And, astoundingly, women’s preferences for men who are already attached may vary according to where the women are in their menstrual cycle. For example, among women who have partners of their own and are in the less fertile phase of their cycle, there is a relative preference for men who are already attached.19

There is thus a kind of unconscious social contagion in perceptions of attractiveness from one woman to another. This makes perfect sense from an evolutionary perspective. Copying the preferences of other women may be an efficient strategy for deciding who is a desirable man when there is a cost (in terms of time or energy) in making this assessment or when it is otherwise hard to decide. While a woman can, with a glance, assess for herself various attributes of a man that might be associated with his genetic fitness (his appearance, his height, his dancing ability), other traits related to his suitability as a reproductive partner (his parenting ability, his likelihood of being sweet to his kids) can require more time and effort to evaluate. In those cases, the assessment of another woman can be very helpful. In fact, psychologist Daniel Gilbert has shown that a woman can do a better job of predicting how much she will enjoy a date with a man by asking the previous woman who dated him what he is like than by knowing all about the man.20 This fact has been exploited for commercial purposes: there is a matchmaking website that only allows men to post if they are “recommended” by a former girlfriend.

In direct mate choice, you choose who you like, but in indirect mate choice of the sort we have been considering, you choose who others like. Indirect mate choice can even lead people to choose mates with characteristics that they did not previously care about. A slight preference by some women for men with tattoos, for example, can lead hordes of men to get tattoos and inspire other women to want men who have them.

Perhaps not surprisingly, men react differently to social information. While they clearly have shared norms about what is attractive in a woman, contextual cues in men can actually operate in the opposite way.21 College-age women were more likely to rate a man as attractive if shown a photograph of him surrounded by four women than if shown a photograph of him alone. But college-age men were less likely to rate a woman as attractive if she was shown surrounded by four men than if she was shown alone. This makes evolutionary sense: when selecting mates, males tend to be less choosy than females and so are less concerned with the opinions of anyone else to begin with. But the presence of other men conveys information of a different sort, namely, that there might be time-consuming (and stressful) competition to secure the woman’s interest.

Hence, social networks affect our relationships in two important ways. First, structural features of our position in the social network can affect whether people think we are attractive. Do we have a partner already? How connected are we? Do we have many or few partners and friends? Others notice such things about us because they say something about who we are. Second, the social network can spread ideas and change attitudes toward attractiveness. Specific preferences for the opposite sex diffuse, and both men and women come to value partners with certain appearances based on what their friends think. Of course, our friends and families also provide explicit comments on our partners and have a conscious influence on our perceptions and behaviors as well.

Unfortunately, detailed data regarding entire social networks and how sexual attitudes and behaviors spread in networks have been very scarce, and most networks that have been studied over the past century have involved only thirty to three hundred people or so. Recognizing the importance of social networks and anticipating a need for data to study them and their role in sexual behavior and other phenomena (such as youth violence, occupational success, and so on), investigators in North Carolina, including sociologists Peter Bearman, Richard Udry, Barbara Entwisle, and Kathleen Harris, designed and launched an ongoing, nationwide social-network study of American adolescents in 1994.

Known as the Add Health study, this landmark survey was administered to a whopping 90,118 students in 145 junior-high and high schools all around the United States. About 27,000 of the students and their parents were selected for follow-up surveys in 1994, 1995, and then again in 2001. Hundreds of questions were included on the survey, addressing everything from feelings about friends and family, to participation in church and school clubs, to risky behaviors like taking drugs or engaging in unprotected sex. Each student was asked to identify up to ten friends (five male and five female), most of whom—crucially—were also in the sample. The study also collected information about people’s romantic partners. All of this allowed scientists to see for the first time, very large, detailed, and comprehensive social networks and to discern the precise architecture of a person’s social ties as it changed across time. We can use these data to identify who is at the center of the network and who is at the periphery, who is located in tightly knit cliques and who prefers to associate with several different groups.

Ties between parents and their adolescent children were critical in the transmission of norms and modeling of behavior. For instance, one study that used the Add Health data showed that girls with a close relationship with their fathers were less likely to become sexually active.22 However, much more important than parents are the peers in an adolescent’s network. Add Health studies have shown that the number of friends, the age and gender of those friends, and their academic performance all affect the onset of sexual activity.23 Friends’ religiosity also affects whether adolescents report having sex, and the effect is strongest in dense social networks, where the adolescents’ friends tend to be friends with one another.24

What these studies show is that sexual behavior can spread from person to person, and the impact the network has depends on how tightly interconnected people are. But sometimes the story is more complicated. Peter Bearman and his colleague Hannah Brückner explored “virginity pledges,” a phenomenon that grew out of a social movement sponsored by the Southern Baptist Church, where teens pledge to abstain from sex, typically until marriage.25 The initial results, accounting for a range of other influences, showed that pledging substantially and independently reduced the likelihood of sexual debut. However, a much more nuanced picture emerged when the investigators looked at the effect more carefully within the social context of each school.

In a small number of “open” schools, where most opposite-sex friendships and romantic ties occur with individuals outside the school, more pledgers indeed meant delayed sexual debut. Surprisingly, though, in “closed” schools, where most ties occur inside the school, more pledgers meant a greater likelihood of sexual debut. These findings suggest that the pledge movement is an identity movement and not solely about abstaining from sex. In closed schools, adhering to this movement might be beneficial (in terms of delaying sex) when one is in the minority, but if pledging becomes the norm, the psychological benefits of a unique identity are diminished, and the effect is lost. It’s not just the pledge itself that constrains behavior; it’s whether the pledge confers a unique status. Riding a motorcycle and wearing a black leather jacket emblazoned with a skull and crossbones may give you a special identity in a place where few people own motorcycles, but in a place where everyone rides a motorcycle, it may simply mean you like to save gas.

Of course, peer norms can also increase sexual behavior. In fact, peers are more likely to promote sex than discourage it. Adolescents who believe that their peers would look favorably on being sexually active are more likely to have casual, nonromantic sex.26 Engaging in oral sex with a partner can actually make one more popular among one’s friends.27 These kinds of peer pressures assuredly underlie the changing mores regarding oral sex seen among American teenagers in the late 1990s. And related studies in adults have shown that people with more partners also have more variety in their sex lives and that they “innovate” more in terms of sexual practices.28

Romantic and sexual practices as diverse as contraceptive use, anal sex, fertility decisions, and divorce are all strongly influenced by the existence of these behaviors within one’s network. For example, in a paper entitled “Is Having Babies Contagious?” economist Ilyana Kuziemko examined eight thousand American families followed since 1968 and found that the probability that a person will have a child rises substantially in the two years after his or her sibling has a child. The effect is not merely a shift in timing but an increase in the total number of children a person chooses to have.29 Similar effects have been documented in the developing world, where decisions about how many children to have and whether to use contraception spread across social ties.30

We can even understand the increasing acceptability of homosexuality as a social-network process. In 1950, there were probably as many gay people as there are now, but they were by and large deeply closeted. San Francisco politician and gay-rights activist Harvey Milk explicitly pushed his fellow activists to come out to their family members, knowing what effect it would have on the network. As the acceptance of homosexuality gradually increased, more and more people came out of the closet, and so more and more people became aware of gay people in their social network, one or two degrees from them. Uncle Harry, the man next door, the coworker, the friend’s friend: all were gay and quite normal and as likely as any heterosexual to be nice to you. This in turn led to a positive-feedback loop, further increasing the acceptability of being gay and the number of people coming out.

Unfortunately, the process can also work in reverse, and stigmatization and discrimination can spread too. The balance in this example and all others we will consider is usually determined by something external to the network. Just as a germ and an index case (the first person to get sick) are required to start an epidemic (otherwise, there is nothing happening), something outside the network is often required to get the spread of a new norm, such as tolerance, going—a key issue in social contagion that we will return to in chapter 4.

Without the tremendous efforts by people like the team at Add Health to collect data about sex and relationships, we would know very little about how sexual practices spread through social networks. In chapter 8, we will explore how the current revolution in network science is being driven in part by the sudden availability of enormous data sets from online sources. It is little wonder, then, that some of the first observations about how connections affect us also coincided with the first efforts to collect data on a society-wide scale in the nineteenth century.

When the British parliament created the Registrar General’s Office in 1836 to track births and deaths in England, it did so in order to assure the proper transfer of property rights between generations of the landed gentry. Quite by accident, it also wound up creating fertile ground for the study of human connection. The man appointed to be the first compiler of abstracts in this newly created office was no petty bureaucrat. William Farr was a physician of humble origins and great creativity who used this opportunity to establish the first national vital statistics system in the world. Over the next four decades, he would proceed to analyze these statistics in ways unanticipated by either parliament or the gentry.

Vital statistics were to Farr what the Galapagos finches were to Charles Darwin: an inspiration for a whole new science, and the key to a variety of seminal insights about the human condition. At first, Farr explored the mortality rates of different occupations, the optimal way to classify diseases (his system is still in use today), and the mortality associated with being in different insane asylums. But in 1858, using data from France, Farr discovered something even more notable. His analysis demonstrated that people who were married lived longer than those who were widowed or single.

Farr had inadvertently waded into a debate that had been started in 1749 by the French mathematician Antoine Deparcieux who had investigated the longevity of monks and nuns. Deparcieux claimed that people living in “single blessedness” lived longer than those who were not sequestered and not celibate. In opposition to Deparcieux, other commentators at the time were worried that “the suppression of a physiological function [namely, sex] is prejudicial to health.” So, the question was this: is celibacy good for your health, or not?

In his 1858 paper, “Influence of Marriage on the Mortality of the French People,” Farr was the first to convincingly answer the question. He was able to document the health benefits of marriage, and, conversely, the adverse health consequences of never marrying or of becoming widowed. As Farr put it, “A remarkable series of observations, extending over the whole of France, enables us to determine for the first time the effect of conjugal condition on the life of a large population.” Farr analyzed the data of twenty-five million French adults and concluded: “Marriage is a healthy estate. The single individual is more likely to be wrecked on his voyage than the lives joined together in matrimony.”31 With detailed tables, he showed that, for example, in 1853, among men aged twenty to thirty, there were 11 deaths per 1,000 unmarried men, 7 per 1,000 married men, and 29 per 1,000 widowers. For men aged sixty to seventy, the analogous numbers were 50 per 1,000, 35 per 1,000, and 54 per 1,000.

The story was basically the same for women, although Farr did note that, among women at young ages, being unmarried (and presumably chaste) seemed to prolong their lives. Farr surmised that this probably reflected the increased incidence of death during childbirth for married women—as he put it, the “sorrows of childbearing”—which was very high in that century.

Not long after Farr’s observations, other scientists began to speculate about the reasons marriage appeared to extend life. Their explanations, it turns out, are still with us today, though we understand them much better than we did 150 years ago. Figuring out how a connection between two people improves survival helped lay the groundwork for understanding how the connection among many people in complicated social networks affects our health, as we will see in the next chapter. But it also laid the groundwork for social-network science more generally, with respect to a host of phenomena. A couple is the simplest of all possible social networks, and marital health effects illustrate how connection and contagion work.

Some observers in the late nineteenth century argued that marriage merely appeared to offer health benefits; what was really going on, they said, was that married people seemed healthier due to a selection bias. Unhealthy people were less likely to get married, and healthy people were more likely to get married. Writing in 1872, Douwe Lubach, a Dutch physician, argued that those with “physical handicaps, mental sufferings, or infamy” would not marry, thus causing those who did marry merely to appear healthier as a result of marriage.32 And the mathematician Barend Turksma, writing in 1898, argued that “those with the least vitality, hardly able to provide for themselves, are almost all obliged to spend their life unmarried.”33 That is, the same factors that are responsible for shorter life—whether poverty, mental illness, or other social, mental, or physical limitations—are also responsible for being unable to get married. Consequently, these commentators identified a thorny problem: which came first, health or marriage?

Nineteenth-century observers could not tell. Scientific confusion persisted for a hundred years until the 1960s, when a spate of papers on the topic appeared. A key paper, published in the British medical journal the Lancet, was entitled “The Mortality of Widowers,” and it again used data from the General Register Office.34 It analyzed the mortality of 4,486 widowed men for up to five years after the death of their wives, and it did something that Farr could not: it followed the men across time after their wives died and documented when, precisely, the men experienced an increased risk of death. The authors found that the mortality rate was 40 percent higher than expected for the first six months after a spouse’s death and then returned to the expected rate shortly thereafter. This spike in mortality has been documented many times since. The close proximity in time of the increased risk of death following a wife’s death was the first piece of evidence that supported a causal connection between the death of the wife and the death of the husband. Something about being connected was improving health, and something about losing the connection was worsening health, if only for a while.

Putting aside chance, there are three overarching explanations for this phenomenon. First, like the nineteenth-century scientists, the twentieth-century authors of the Lancet paper noted the possibility of homogamy. As these authors noted, homogamy includes “the tendency of the fit to marry the fit, and the unfit the unfit.” If unfit people marry each other, we should not be surprised to see that premature death in one spouse would be followed by illness or premature death in the other. They were both unhealthy to begin with.

A second explanation, which began to be seriously addressed in the 1960s, was that there could be a joint unfavorable environment. Maybe the two spouses were both exposed to things that made them more likely to die, such as toxins in the environment or a careening bus. If the bus injured them both but left the husband to survive a bit longer than the wife, we clearly would not say that the wife’s death caused the husband’s death even if we observed that his death quickly followed hers. This problem is known as confounding because this extraneous third factor (the toxins, the bus) confounds the ability of scientists to discern what is really going on.

Third and most important, as Farr himself argued, there might be a true causal relationship between marriage and health. Focusing on widowhood and the health costs of losing a spouse, the authors of the Lancet paper correctly pointed out that the death of a man’s wife might cause his death, and they provided the quaint illustration that “widowers may become malnourished when they no longer have wives to look after them.”

There are a host of biological, psychological, and social mechanisms for such a causal effect of widowhood in both men and women. As the Lancet authors noted, “tears, slowed movements, and constipation cannot be the only bodily effects [of widowhood], and whatever may be the other effects, they could scarcely fail to have secondary consequences for resistance to various illnesses.” Other scientists writing at this time began to refer to the widowhood effect as “dying of a broken heart,” and people actually began to take this metaphor literally, searching for, and ultimately finding, evidence that the risk of heart attack rises immediately after the death of a spouse.35 Something about being connected to a spouse affects our bodies and our minds.

Amazingly, these three explanations—homogamy, confounding, and a true causal effect—are relevant not only to couples and the struggle to understand whether marriage is salubrious. They are, it turns out, also relevant to other phenomena beyond health and even to the operation of social networks more generally. For example, when we considered the spread of emotions in a family, we had to decide whether happiness really spread or whether grandma brought over a puppy, making everyone in the family happy at once. Or, to pick an economic example: Why might two friends both be poor? Did they befriend each other because they were poor? Did they go into business together and become poor together because the business failed? Or did one become poor and the other follow suit by copying the bad spending habits of the first one?

Modern research confirms that marriage is indeed good for you, but the benefits for men and women are different. If we could randomly select ten thousand men to be married to ten thousand women, and if we could then follow these couples for years to see who died when, statistical analysis suggests that what we would find is this: being married adds seven years to a man’s life and two years to a woman’s life—better benefits than most medical treatments.36

Recent innovative work by demographer Lee Lillard and his colleagues, Linda Waite and Constantijn Panis, has focused on untangling how and why this is so. Their research has analyzed what happened to more than eleven thousand men and women as they entered and left marital relationships during the period from 1968 to 1988.37 The group carefully tracked people before they married until after their marriages ended (either because of death or divorce) and even any remarriages. And they closely examined how marriage might confer health and survival benefits and how these mechanisms might differ for men and women.

The emotional support spouses provide has numerous biological and psychological benefits. Being near a familiar person—even an acquaintance, let alone a spouse—can have effects as diverse as lowering heart rate, improving immune function, and reducing depression.38 Spouses provide social support to each other and connect each other to the broader social network of friends, neighbors, and relatives. In terms of practical support, the most obvious way that husbands and wives help each other is via the economies of scale derived from a joint household—it costs less to live together than to live apart. Having a spouse is also like having an all-purpose assistant who can at least theoretically meet all kinds of needs. Spouses are reservoirs of information and sources of advice, and hence they influence each other’s behavior. They have opinions about everything from whether we should wear our jeans or our seat belts, whether we should eat out or order in, whether we should save more money or blow it all. In part because they have a devoted advocate for their interests, married people choose higher-quality hospitals and are less likely to suffer complications from medical treatment compared to the widowed or the unmarried.39

In terms of gender roles, Lillard and Waite found that the main way marriage is helpful to the health of men is by providing them with social support and connection, via their wives, to the broader social world. Equally important, married men abandon what have been called “stupid bachelor tricks.”40 When they get married, men assume adult roles: they get rid of the motorcycle in the garage, stop using illegal drugs, eat regular meals, get a job, come home at a reasonable hour, and start taking their responsibilities more seriously—all of which helps to prolong their lives. This process of social control, with wives modifying their husbands’ health behaviors, appears to be crucial to how men’s health improves with marriage. Conversely, the main way that marriage improves the health and longevity of women is much simpler: married women are richer.

This cartoonish summary of a large body of demographic research may seem quite sexist and out-of-date. In fact, some demographers have commented that perhaps this is just the age-old story of “trading sex for money”: women give men intimacy and a sense of belonging, and men give women cash. It is important to note that these studies involved people who were married in the decades when women had much less economic power than men. But, nevertheless, these results point to something more profound and less contentious, namely, that pairs of individuals exchange all kinds of things that affect their health, and that such exchanges—like any transaction—need not be symmetric either in the type or the amount exchanged.

How risk of death changes over time for men and women before, during, and after marriage.

The difference in mechanism across genders and the variation in what is exchanged are also reflected in the timing of health benefits that accrue to men and women when they enter into marriage. When men get married, they experience a sharp and substantial decline in their risk of death (the prompt elimination of stupid bachelor tricks). Women, on the other hand, do not derive an immediate health benefit. It takes longer for them, and their risk of mortality declines more gradually. Moreover, the decline in their risk of death is more modest. These patterns are shown in the illustration.

As we have discussed, something similar happens at widowhood. When a wife dies, the husband’s risk of death rises abruptly and dramatically, so that men who lose their wives are between 30 percent and 100 percent more likely to die during the first year of widowhood. This is a clear and persistent finding. Yet, within a few years, widowed men’s risk of death declines from this peak.

There has been a lot of debate about whether there is a widowhood effect for women. After Farr’s seminal research and until the 1970s, many analyses concluded that women did not suffer any widowhood effect. Then researchers started publishing results that were all over the place, some suggesting that women did not suffer a widowhood effect, and some that they did but to a lesser extent than men. Recent work has concluded that both men and women suffer a widowhood effect, and that it may even be comparable in size.41

Questions remain, however, about gender differences in other aspects of the widowhood effect. For example, women might recover sooner from the shock of widowhood than men. Why might there be any discrepancy in magnitude, duration, or mechanism of the effect? Do men suffer more health consequences than women when their spouses die because men love their wives more than women love their husbands? No. Rather, it may be that when men die, the thing they brought to the marriage that had the greatest impact on their spouse’s health, namely money, is still around—in the form of assets such as a house and a pension. Conversely, when women die, the thing they brought to a marriage that most affected their partner’s health, namely, emotional support, a connection to others, and a well-run home, disappears. Widowed men often find themselves cut off from the social world and lacking social support. Since men in most societies have tended to cede homemaking to women, widowed men also often find their meals irregular and their homes—if not their entire lives—in disarray.

We do not know yet about same-sex marriage. It could be that married homosexual men each gain seven years of life, and homosexual women each gain two years, just like heterosexual men and women. But it is also possible that married homosexual men gain two years, while homosexual women gain seven. If this were the case, it would mean that it is not marriage per se that is salubrious but, rather, marriage to a woman.

These differences in men and women highlight the fact that whom we are connected to may be just as important as whether or not we are connected. Two people might have different numbers of friends, or they might have the same number of friends, but one person might have educated friends and the other uneducated friends. This difference in the nature, and not just the number, of the social contacts itself is often significant.

For example, both the age and race of your spouse can have an effect on your health. Marriage to a younger woman is good for a man whereas marriage to a younger man is not good for a woman. A variety of investigators have shown that the bigger the age difference (up to certain limits) between an older husband and a younger wife, the better for both parties when it comes to the health benefits of marriage.42 Some have interpreted this finding to be consistent with the “trading sex for cash” caricature: if marriage works to provide health by improving women’s economic well-being and men’s social well-being, then, on average, older men and younger women are better able to provide these benefits to each other.

What we are describing here are average effects, of course, and many people have different experiences. It is likely that in couples where the wife is the principal breadwinner and leaves behind substantial assets, and where the husband’s role is to provide social connection, the death of a wife may not be as harmful to the husband’s health. In fact, in more socially egalitarian societies, the widower effect may be more similar in men and women.43 This is what we would expect if the gender roles of “breadwinner” and “social connector” create the relative health advantages for husbands and wives.

Men and women may also differ in their ability to offer and receive the benefits of marriage, which raises an important question: Do men benefit more from marriage than women because men stand to gain more from marital connection or because women have more to offer? Or both? One way that we approached these broader questions, in conjunction with sociologist Felix Elwert, was to study racial variation in the widower effect. We found that white couples suffer a widowhood effect, but black couples do not. There are a variety of possible explanations for this result, but the most compelling seems to be that the health benefits of marriage endure after the death of a spouse in black couples but not in white couples. But, if you are a white man, why do you fare worse than a black man during bereavement? Is it because you are white, or because you were married to a white woman?

We developed a large sample of interracial couples to sort this out and found that men married to black women did not experience a widowhood effect, whereas men married to white women did, regardless of the man’s own race.44 But how could a wife’s race affect her husband’s mortality during widowhood? Clearly, any effect on the husband’s health cannot relate to the wife’s ongoing efforts. She is dead, after all. Rather, the effect must be caused either by aspects of the dissolved marriage that vary between racial groups or by the characteristic circumstances of the state of widowhood that vary between racial groups. For example, maybe the families of black wives are more supportive during the bereavement of husbands, on average, than are the families of white wives.

This may in turn relate to the greater rejection of intermarried couples by white relatives than by black relatives. Since wives are typically responsible for maintaining kinship networks, black men married to white women may be more likely to suffer isolation, disconnection from their social network, and lack of support from their in-laws upon the death of their spouse than are black men married to black women or white men married to black women. Hence, the difference in marriage benefits between women and men is very likely to be a consequence of the greater ability of women to keep their spouses connected.

Social networks function in large part by giving us access to what flows within them. We know for example that marriage to an educated, rich, or healthy spouse is better for our health than marriage to a person lacking these qualities. But this is not merely because of our spouse’s identity, it is because of what they actually give. Healthy or educated or rich partners are better able to provide useful information, social support, and material goods. And the flow of love and affection between spouses is also critically important. One study of 1,049 couples followed for eight years found that a bad marriage accelerates the normal decline in health as people age. This is partly due to negative interactions with your spouse putting stress on your cardiovascular and immune systems, a kind of wear and tear that accumulates over time. As a result, the death of a spouse who does not love and care for you, or whom you do not love and care for, does not harm your health as much as the death of an intimate spouse.45 It is little wonder, then, that we spend so much time searching for partners. The qualities of the people to whom we are connected will have a big effect on every aspect of our lives.

You may use lots of different kinds of social networks to help you in your search, whether they are networks of coworkers, Facebook friends, family members, or neighbors. The tendency to have several kinds of relationships (and sometimes many kinds of relationships with the same person) is called multiplexity. Our sexual network is in fact a subset of the larger social network within which we search for partners. In a sense, the latter is a potential network and the former is a realized network (like a network of contacts in a Rolodex, only some of whom become business partners).

If we live in multiplex networks, how we perceive them and how scientists draw them depends on what types of relationships we are focused on, as shown in plate 2. There are many layers, and your position in each layer will determine how connected you are. For example, you might have many friends but few sexual partners. This means you will be more central in the friendship network than you would be in the sexual network, even though both of these are a part of your complete social network. As a consequence, you are more likely to receive things that flow via friendship (like gossip) than things that flow via sexual relations (like sexually transmitted diseases). And some people will have multiple relationships to the same person, like the circled pair in plate 2.

We could use sexual interactions to trace paths through the network that would otherwise seem quite preposterous, or that might not be apparent, say, if we were instead tracing out paths involving business relationships. This observation even prompted American writer Truman Capote to develop a parlor game, which he described as follows: “It’s called IDC, which stands for International Daisy Chain. You make a chain of names, each one connected by the fact that he or she has had an affair with the person previously mentioned; the point is to go as far and as incongruously as possible. For example, this one is from Peggy Guggenheim to King Farouk. Peggy Guggenheim to Lawrence Vail to Jeanne Connolly to Cyril Connolly to Dorothy Walworth to King Farouk. See how it works?”46

An important property of multiplex networks is that they overlap. We might be friends with our spouse, lovers with a coworker, or acquaintances with a neighbor. And when we seek out sexual partners, we typically draw on other kinds of networks. We do not form random ties with simply any other human. We do not choose our dates by throwing darts at the phone book. We get to know our neighbors, coworkers, schoolmates, and others to whom we are introduced, or, less often, meet serendipitously in a manner typically governed by other social constraints.

Thus, we might be able to learn a lot about social networks in general by looking at sexual networks in particular. And these networks are especially important because having sex with someone is clearly a very deliberate and detectable type of social tie. It is the analogue in social-network studies to what death is in medicine: an unambiguous end point. If we want to know who is connected to whom in a network, and we ask you who your friends are or whom you trust, these questions are much more open to vagaries of interpretation than asking whom you have had intercourse with. But by asking that question, it becomes possible to map out social networks in a well-defined way. And by probing how people find others to have sex with, and the other myriad ways that social networks affect our sex lives, we can understand more about human experience and social interaction than just sex. In the next chapter, we discuss how researchers have used sexual networks to study the spread of disease, and how this long-standing work set the stage to completely change the way we think about our health.