In his election-night acceptance speech on November 4, 2008, Barack Obama said, “I was never the likeliest candidate for this office. We didn’t start with much money or many endorsements. Our campaign… was built by working men and women who dug into what little savings they had to give five dollars and ten dollars and twenty dollars to this cause.” In fact, Obama’s team shattered records in fund-raising. By the end of the campaign, he had received $600 million in contributions from more than three million people. In hindsight, Obama’s campaign was described as a perfectly run operation that made few, if any, mistakes. But how did he get people on board before the public perception that things were going well? How did he persuade so many previously uninvolved people to donate money to him and to vote for him, especially those who in the past believed their vote did not count?

In no small measure, Obama succeeded because these “working men and women” felt connected. Obama’s campaign was a historical milestone in all kinds of ways, but the most revolutionary may not have been its fund-raising. Many have commented on Obama’s remarkable ability to connect with voters, but even more impressive was his ability to connect voters to each other.

The 2008 presidential election saw a dramatic increase in the use of the Internet across all political campaigns, but Obama’s in particular took advantage of the power of online social networks and social (person-to-person) media. In fact, Obama’s use of the Web evoked comparisons with John F. Kennedy’s use of television to win the race for the presidency in 1960. Both men forever changed the face of politics through their use of new technology, forcing friends and foes alike to adopt their methods of reaching out to the masses.

Lacking an established base, Obama realized very early that the Internet would be important. In 2004, Howard Dean had used the Internet to challenge traditional candidates, but online social networking had not yet arrived. Dean’s campaign raised a lot of money but failed to mobilize supporters because they were not yet connected to one another. Obama recruited two very talented people to run his online campaign, Joe Rospars, a veteran of Howard Dean’s campaign, and Chris Hughes, one of the cofounders of Facebook.

Hughes built the social networking site My.BarackObama.com, which logged 1.5 million accounts at its peak. Users could discuss the candidate, donate money, and, crucially, organize real-world social activity. Over the course of the campaign, more than 150,000 campaign-related events would take place in all fifty states. Meanwhile, supporters online formed 35,000 groups based on geographic proximity, affiliation with specific issues, and shared pop-cultural interests. Users of iPhones could download an application that made it easy to call friends to encourage them to vote or contribute to the campaign. The application organized telephone contacts by order of importance, listing first those friends in swing states where the election was expected to be close. And in the critical last week of the race, the Obama campaign organized more than a thousand phone-banking events to get out the vote.

According to the Pew Internet and American Life Project, all this activity made a difference.1 Obama supporters were more likely than Clinton supporters to mobilize their friends and family members by signing online petitions and forwarding political commentaries via text, e-mail, or online social networks. In part, this was because younger people were more likely to support Obama, but even with members of the same age group, Obama supporters tended to reach out to their own networks far more often than Clinton supporters did. And the gap between supporters of Obama and McCain was even larger; it would eventually carry Obama to victory.

Many people—whether Republican, Democrat, or Independent—felt inspired by their participation in the 2008 campaign. And many more encouraged their friends and families to vote because “it’s the right thing to do.” But this behavior is somewhat puzzling. Although adults in most democratic countries have the right to vote, each of these votes is just one of millions of others. Politicians frequently tell their supporters “every vote counts,” and people usually say they vote in order to help their candidate win. But under what circumstances will a vote actually do that? This basic question has led to a series of investigations by brilliant social scientists, each building on the work of previous thinkers, but all leading, alas, to the same conclusion. Rationally speaking, each vote doesn’t count. The reason we vote, it turns out, has a lot to do with our embeddedness in groups and with the power of our social networks.

In 1956, Anthony Downs, an economics graduate student at Stanford, decided to apply the science of “rationality” to the study of politics.2 He did not mean this as an oxymoron. The word rationality takes on a very specific meaning here, and it is not the opposite of crazy. Rationality means three simple things. First, rational people have preferences and know them. So you prefer an orange to an apple, a dollar to a penny, or a Democrat to a Republican. Or you may be indifferent. The point is that you can compare two things, and you know which one you like better or you know you like or dislike them equally. Second, rational people’s choices are consistent. If you would rather have the orange instead of the apple, and the apple instead of the pear, then you will not choose the pear over the orange. Consistency is analogous to transitivity in algebra: if A > B and B > C, then it must be true that A > C. And third, rational people are goal oriented. Once we know what we want, we try to get it.

Downs wanted to see whether voting could be understood as rational and, if so, under what circumstances. He noticed that politics in the United States was often about two choices, not more. Vote for the Democrat or the Republican. Lower taxes or raise them. Veto the bill or sign it. In fact, our government is replete with formal procedures that reduce a wide range of choices to just two. Downs assumed that voters would focus on one of the alternatives (say Barack Obama) and think carefully about everything that would happen if this alternative were chosen. They would then assign a value to this outcome that described the benefit. In other words, they would try to answer the question, how useful would an Obama presidency be to me personally? Next they would think carefully about the other alternative (say John McCain) and assign a value to that future outcome. Each voter would then vote for the alternative that yielded the greater value for themselves.

But voting is not a required act in the United States, nor is it in most countries in the world. What makes someone decide to even bother showing up at the polls? Downs noted that voters would also take into account the costs of voting. We might need to take time away from our workday or leisure activities to go to the polls. For example, in the 2004 U.S. presidential elections, some voters in Ohio waited in the rain for hours to cast their ballots. It might also be personally costly to spend time collecting information about the election so as to know whom to vote for.

Taking costs and benefits into account, each person would then decide whether to vote. If a voter thought she would benefit equally from both alternatives, she might decide not to pay the costs of voting and stay home. Downs called this rational abstention—it makes sense for some people not to participate because they literally think, “There’s not a dime’s worth of difference between the two.” Conversely, people who believe one alternative is much better than the other are likely to care a lot more about the outcome and would therefore be more likely to stand up and be counted, even if the costs of voting are very high. Those Ohio voters soaked to the bone are just one example of such highly motivated individuals.

But does this really explain why people vote, especially when they may also think that they cannot influence the outcome? Do they simply calculate the benefits and costs and make a choice?

Actually, it’s more complicated than that. William Riker, a tremendously influential political scientist at the University of Rochester in the 1960s and 1970s, pointed out that Downs had overlooked the important fact that not just one voter makes this decision but millions.3 Thus, to determine the value of voting, we need to decide not just who we like better but also the probability that our action—our vote—will help that person win. Calculating this probability may seem like an impossible task because there are so many possible outcomes. Obama could beat McCain by 3 million votes. Or he could beat him by 2,999,999, or he could lose to McCain by 1,345,267. Or… There are literally millions of possible outcomes.

Of course, there is only one circumstance in which an individual vote matters. And that is when we expect an exact tie. To see why this is true, ask yourself what you would do if you could look into a crystal ball and see that Obama would win the election by 3 million votes. What effect would your vote have on the outcome? Absolutely none. You could change the margin to 2,999,999 or to 3,000,001, and either way Obama still wins. Notice that the same reasoning is true even for very close elections. No doubt some citizens of Florida felt regret about not voting in 2000 when they learned that George W. Bush had won the state (and therefore the whole election) by 537 votes. But even here, the best a single voter could do would be to change the margin to 536 or to 538, neither of which would have changed the outcome.

So what is the probability of an exact tie? One way of looking at this is to assume that any outcome is equally possible. Suppose 100 million people vote for Obama or McCain. McCain could win 100 million to 0. Or he could win 99,999,999 to 1. Or he could win 99,999,998 to 2. You get the idea. Counting all these up, there are 100 million different possible outcomes, and only one will be a tie. Because roughly 100 million people vote in U.S. presidential elections, that would mean that the probability of a tie is about 1 in 100 million.4

The exact probability is obviously much more complicated than this, as it is unlikely that Obama or McCain would win every single vote cast. Close elections are probably more likely than landslides. So instead of theorizing about the probability of a tie, we could study lots and lots of real elections to see how often a tie happens. In one survey of 16,577 U.S. elections for the House and Senate over the past hundred years, not one of them yielded a tie.5 The closest was an election for the representative for New York’s 36th congressional district in 1910, when the Democratic candidate won by a single vote, 20,685 to 20,684. However, a subsequent recount in that election found a mathematical error that greatly increased the margin, meaning there are actually no examples of single-vote wins.

In this survey of elections, the average number of voters per election was about one hundred thousand. This is far fewer than the millions who turn out for a national election, and therefore we would expect the odds of a tie in a national election to be even lower. However, calculating this probability is not easy. U.S. presidential elections are complicated because they are not decided by the popular vote. Instead, each state has a number of electors it sends to an electoral college to choose the president. Bigger states get more electors, and most states award all their electors to the candidate who wins the popular vote in their state. As a result, it is possible to win a few big states by a narrow margin and gain the presidency by winning the electoral college vote while losing the popular vote (as George W. Bush did in 2000). Taking all of these complications into account in one big statistical model, political scientists Andrew Gelman, Gary King, and John Boscardin used real data from one hundred years of presidential elections to model the vote within each state and the effect this would have on electoral college votes.6 Their model showed that the chance of a tie in any state changing the state’s electoral college vote and hence the outcome was about 1 in 10 million.

So let’s go back to the original question posed by Anthony Downs. Suppose you were deciding whether to vote in the 2008 election. When, given all this, does it make rational sense to vote?

First, you have to put a value on the difference between a McCain presidency and an Obama presidency. One way to arrive at this value is to ask yourself, How much would I be willing to pay to be the only person who gets to choose whether McCain or Obama is president? You can go to the bank and withdraw any amount you like. How much would you hand over to be the kingmaker, the one person who chooses who runs the country for the next four years? One dollar? Ten dollars? One million dollars? When undergraduates answer this question, they usually give amounts of less than $10, which is astonishing since this is probably the greatest value anyone could get for a $10 purchase. However, for the sake of argument, let’s say you think it is a very important decision and you are willing to spend $1,000 of your own money to be the only person who chooses the next president of the United States.

Second, you have to account for the fact that, by voting, you get the opportunity to determine the election’s outcome only when there is an exact tie. Otherwise, the outcome will not change whether you vote or not. So the value of voting is not $1,000; instead, it is a 1 in 10 million chance to obtain the $1,000 value.

Third, and finally, you have to compare your anticipated benefit to the costs of voting. Most people say that the costs of gathering information and going to the polls are not that great, so for convenience let’s assume they are $1. They could be much higher, of course, but they are almost certainly greater than zero.

Hence, now that we have your costs and benefits all worked out, the rational analysis of voting suggests that the decision to vote equates roughly with the decision to pay $1 for a lottery ticket that gives you a 1 in 10 million chance of winning a $1,000 prize. Las Vegas would love to sell these tickets. If they could sell 10 million tickets, they would make $10 million dollars and owe just $1,000 in prize money. But even the most ardent gambler would probably refuse to buy them, knowing that the odds are extremely unfair. The average person would probably need other inducements to buy a ticket, because slot machines, blackjack tables, and roulette wheels all have vastly better odds. Even state lotteries that use funds from ticket sales to provide public services rather than prize money typically offer people millions of dollars in winnings, not thousands, for odds like these. And so we are left with the same puzzle we began with. Why do millions of people vote in spite of these odds and payoffs? What is it about elections that make them different from lotteries?

This rational analysis of voting is extraordinarily depressing for (at least) three reasons.

First, it suggests that the core act of modern democratic government makes absolutely no sense. Economists would call voting irrational because it violates the preferences of the people who engage in it. For some reason, people decide to vote even though they would not buy a lottery ticket with identical odds, cost, and payoff. Economists typically think that people who vote are making a mistake or that there are other benefits to voting that we have not considered. For example, Downs himself noted that people might vote in order to fulfill a sense of civic duty or to preserve the right to vote. Later scholars have pointed out that people might vote because they enjoy expressing themselves—in the same way they enjoy expressing themselves when they cheer for their favorite team at a ballgame.

Second, learning about the irrationality of voting actually depresses turnout. In 1993, Canadian political scientists André Blais and Robert Young gave a ten-minute lecture on the rationality of voting to three of their classes and compared their students’ voting behavior to that of students in seven other classes who did not hear the lecture. Perhaps not surprisingly, the students who heard the lecture were significantly less likely to vote.7 Meanwhile, back in the United States, on Election Day in 1996, the Lawrence Journal-World published a guest column by Kansas University political scientist Paul Johnson about his reasons for not voting. He outlined the rational argument and noted that because of it he had not voted in the past thirty years. Within days there were several pointed letters to the editor denouncing his opinion and openly calling for his dismissal from the university. Johnson was not fired, but he did register to vote a week later in part to calm the controversy.8

Third, the inability to explain the decision to vote calls into question the rational analysis of all political behavior. Since we cannot use cost-benefit analysis to explain something as basic as voter turnout, some scholars argue that it makes no sense to apply rationality to other decisions such as who to vote for, whether to run for office, how to bargain with political adversaries, and so on. Instead of making rational choices that account for the costs and benefits of their actions, political actors might be affected by their emotions or by specific contexts that could not be generalized. In 1990, Stanford professor Morris Fiorina (one of William Riker’s students from Rochester) dubbed this perplexing voting problem “the paradox that ate rational choice.”9 This is academics’ way of saying that it makes no sense.

It was in this highly charged environment that we began our own work on voter turnout. We thought that scholars on both sides of the rationality debate were missing a crucial point: people do not decide in isolation whether or not they will vote. Thinking about the problem from the perspective of the individual voter misses the big picture entirely.

A large body of evidence suggests that a single decision to vote in fact increases the likelihood that others will vote. It is well known that when you decide to vote it also increases the chance that your friends, family, and coworkers will vote.10 This happens in part because they imitate you (as discussed in previous chapters) and in part because you might make direct appeals to them. And we know that direct appeals work. If I knock on your door and ask you to head to the polls, there is an increased chance that you will. This simple, old-fashioned, person-to-person technique is still the primary tool used by the sprawling political machines in modern-day elections. Thus, we already have a lot of evidence to indicate that social connections may be the key to solving the voting puzzle.

Yet, even these insights about the social determinants of voting never went beyond the first step. Just like Anthony Downs and the other modelers who assumed all individuals were independent, the scholars who noted the social influence of one person on another assumed that pairs of people also acted independently. If I vote, it may help to influence my wife to vote, but the buck stops there. Scholars never wondered what might happen if they considered larger groups of people. Maybe the key to why we vote—and why it is rational for us to vote—is that we are all connected in larger networks.

As a child of the 1970s, James watched far too much television. He remembers one commercial in particular in which a woman is so enthusiastic about her new shampoo that she tells two of her friends about it. The screen then splits to show the two friends, and the voice-over says, “And she told two friends… and she told two friends… and so on… and so on… and so on…” The number of women on the screen doubled each time the voice-over said “she told two friends” so that by the end of the commercial sixty-four women were all using the shampoo.

This commercial is still used today to illustrate social marketing, but the idea that intrigued us was this: What if we replaced the act of trying out a new shampoo with the act of voting? What if a single act of voting not only influences my friend but also my friend’s friend? One person might have just five friends, but if each of those friends also has five friends, then maybe a single person can influence all twenty-five of them as well, and all 125 of their friends’ friends. It is easy to see how the number of people affected by a single decision can go up quickly. With an average of ten friends and family per person, we could easily imagine having influence over ten, then one hundred, and then one thousand people. And if one vote led to not just ten but to hundreds or thousands of votes, then maybe the likelihood of affecting the outcome of the election would be magnified enough to explain why so many people do vote. We may not see all the people we affect, but we may sense that our vote really might make a difference.

The earliest research on the social spread of political behavior came in the classic voting studies of Columbia social scientists Paul Lazarsfeld and Bernard Berelson that took place in the 1940s in the towns of Erie, Pennsylvania, and Elmira, New York.11 Although they did not collect information about the whole network that interconnected all their subjects, they did ask people to discuss who influenced them and by what means, and this gave us the very first picture of how important networks can be in political behavior. One of the key findings from these studies was that the media does not reach the masses directly. Instead, a group of “opinion leaders” usually acts as an intermediary, filtering and interpreting the media for their friends and family who pay less attention to politics. In other words, the media appeared to work by getting its message to those who are most central in the social network. Politicians themselves follow a similar strategy, seeking endorsements from local leaders and targeting frequent voters rather than trying to persuade those at the periphery of the network who may or may not participate.

Later research by Robert Huckfeldt and John Sprague in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s would innovate on these earlier studies.12 Their research in South Bend and Indianapolis, Indiana, and St. Louis, Missouri, used a “snowball” design, asking people to talk about friends who influenced them and to give the researchers their friends’ contact information so they could be in the study too. Huckfeldt and Sprague found that when it came to politics, birds of a feather flocked together. Democrats tend to be friends with other Democrats, and Republicans tend to be friends with other Republicans. Liberals are connected to liberals, and conservatives to conservatives. Voters tend to discuss politics with others who vote. That is, people appear to be clustered together politically, acting and believing in concert with the people who surround them.

We wondered whether this insight could shed light on why people vote at all. We also wondered whether a strong similarity in people’s local networks could arise from a spread of political behaviors and ideas. Did people choose to associate with those who resembled them, or did they induce a resemblance by influencing their peers? Huckfeldt and Sprague showed us the person-to-person effect, but now we wanted to know how and whether it might spread to other people in the network. Could one vote really spur thousands of others to vote in a turnout cascade?

In order to find out just how far we could push the idea that voting might spread from person to person to person, we decided to try to answer the question, if I vote, how many other people are likely to vote as well? Many interactions between friends and family might affect the decision to vote. People might be affected by merely observing their acquaintances’ behavior (Do they vote? Do they participate in community or group activities? Do they have political signs in their yards?). They might also be affected by political discussions with their acquaintances. Even chance encounters might be influential. As Huckfeldt writes: “The less intimate interactions that we have ignored—discussions over backyard fences, casual encounters while taking walks, or standing in line at the grocery store, and so on—may be politically influential even though they do not occur between intimate associates.”13

Several election studies show that we typically talk to only a few people about politics; in one study in which people were asked to name their “discussion partners,” about 70 percent reported fewer than five (on any topic).14 Subjects reported talking with each of their discussion partners about three times per week, and most people said they talked about politics “sometimes” or “often.” And while elections are not always on people’s minds, a large number of people reported paying attention to campaigns, especially in the few months immediately prior to an election. Using data from a variety of sources, we estimated that respondents typically have about twenty discussions during the most salient period of a campaign when people are trying to decide whether to vote, but the number of opportunities for influence is probably even greater. A significant percentage of respondents in the Indianapolis/St. Louis Election Study—fully 34 percent—said they tried to convince someone to vote for their preferred candidate, indicating that many people believe there is a chance others will imitate them. These efforts might be aimed at influencing voter choice, but they also convey messages about whether an election is important, which might affect people’s decision to show up on Election Day.

But do these attempts to influence others succeed? If imitation is occurring, then we should see a correlation in behavior between two people who are socially connected. And, in fact, that is exactly what we do see when it comes to voter turnout. Even when we control for alternative sources of similar behavior, such as having the same income, education, ideology, or level of political interest, the typical subject is about 15 percent more likely to vote if one of his discussion partners votes. But does this influence spread beyond that to the rest of the network? As it turns out, we see a correlation between people who are directly connected and also between people who are indirectly connected via a common friend. In other words, if you vote, then it increases the likelihood that your friends’ friends vote as well.

Scholars who study voting behavior consistently find that people tend to segregate themselves into like-minded groups. As a result, most social ties are between people who share the same interests. When people with ideological or class-based interests are not surrounded by like-minded individuals in their physical neighborhoods and workplaces, they tend to withdraw and form relationships outside those environments. In the Indianapolis Election Study, about two out of every three friends had the same ideology as the respondent. In fact, we can even see this on a large scale in recent U.S. elections by looking at the increase in polarization between Republican “red states” and Democrat “blue states.”

Ideological polarization does not affect total turnout, but it does affect how one vote can transform into many votes for your favorite candidate. If liberals and conservatives live side by side, well mixed throughout the population, then a turnout cascade has an equal chance of sending each kind of person to the polls. You might be conservative, but your liberal friend copies you by voting (maybe just to spite you!), and his liberal friend copies him, and her conservative friend copies her, so that by the time the cascade runs out of steam, your vote has influenced an equal number of liberals and conservatives to vote. The net effect would be two extra votes for the liberal candidate and two extra votes for the conservative candidate, so on balance there would be no change. With polarization, however, turnout cascades are more likely to affect like-minded individuals and yield extra votes for your preferred candidate. Suppose instead that your friend is conservative and so is his friend and so is her friend, so that your decision to vote generates four extra conservative votes and no extra liberal votes. If you knew you could get lots of people to support your favorite candidate just by voting, you would probably be more likely to do it than if you thought your vote would get canceled out by a mix of people from the Left and Right. This means that in ideologically polarized environments, the incentive to vote might be magnified by the number of like-minded individuals you could motivate to go to the polls.

Using everything we learned from Huckfeldt and Sprague about real networks of political interactions, we created a computer model to simulate what happens to the whole network when one person decides to vote.15 In each simulation, we let everyone in the network try to influence the people to whom they were connected. We then measured the cascades in which one vote turned into two and then four and then eight, just like the shampoo commercial. Repeating the model millions of times allowed us to see the likelihood of turnout cascades and how many people a person could typically affect through her own behavior.

The results were very surprising. In some cases, one person’s vote spread like wildfire, setting off a cascade of up to one hundred other people voting, even though people typically were directly connected to only three or four other people. On average, one decision to vote would motivate about three other people to go to the polls. Moreover, because liberals tend to associate with liberals and conservatives with conservatives, these cascades would yield sizable increases in the number of people voting the same way. Most of the time, one person’s vote turned into two or more additional votes for their favorite candidate. So it seems that the more polarized we become by befriending only people with similar ideologies, the more motivated we are to participate in politics. This certainly creates a dilemma for people who think polarization is bad and voter turnout is good.

Interestingly, the total number of people voting had virtually no effect on how far the cascades would spread in our computer model. We originally believed that the size of turnout cascades would be bigger in larger populations because of the increased number of people who might be influenced. Instead, we discovered that turnout cascades are primarily local phenomena, occurring in small parts of the population within a few degrees of separation from each individual. As our Three Degrees of Influence Rule suggests, the power of one individual to influence many is limited by the effect of competing waves of influence that emanate from everyone else in the network.

People usually wonder whether computer models like this have meaning in the real world. No one has ever witnessed a turnout cascade, so how can we prove that they exist? Maybe they are just a figment of the modeler’s imagination.

Many results from the model made sense and were already well established. The more often you ask someone to vote, the more likely it is she will vote. This is not surprising. What we needed was an important counterintuitive result that we could verify in the data. And, in fact, one prediction made by the computer model was very subtle and had never before been considered by political scientists. The model suggested that cascades would be largest if they emanated from someone who was in a moderately transitive group (that is, a group where people’s friends know each other). Too much transitivity would mean the group was cut off from the rest of the world, and too little transitivity would mean the group was too disorganized to reinforce its own members’ behavior. People might not know exactly how all their friends are connected, but they probably do have a sense of whether they might be able to reach people beyond their own group.

Hence, if there is a sweet spot for producing voting cascades, then we should expect people in that spot in real life to actually be more likely to vote because they are in a better position to influence many other people to follow suit. By the same reasoning, we should expect the same people to be more likely to try to persuade others to vote. As it turns out, this is exactly what we found in the Indianapolis and St. Louis data. The people who were the most likely to vote were those with transitivity of about 0.5 (meaning that half their friends are friends with one another). People whose friends did not know one another participated less, but so did those in tightly knit cliques of friends. And we recently confirmed these results and found exactly the same effects in a nationwide Gallup survey of networks and voting behavior.

These findings contradict some of the core recommendations made by political scientist Robert Putnam and his colleagues who study the effect of “social capital” on the health of our democracy.16 Putnam argues that highly clustered network ties improve information flow and increase reciprocity at a societal level because everyone is looking out for everyone else. In other words, more tightly knit connections are better for society. However, our work shows that, at a certain point, networks can become so transitive that norms and information simply circulate within groups rather than traveling between them. Like Brian Uzzi’s groups of scientists and Broadway musical producers that we discussed in chapter 5, democratic citizens work best in “small worlds” where some of our friends know one another and others do not.

While our computer model provided some of the first indirect evidence that turnout cascades are real, direct evidence was not far behind. In 2006, Notre Dame political scientist David Nickerson traveled to neighborhoods in Denver, Colorado, and Minneapolis, Minnesota, to conduct a novel experimental study of voter turnout.17 In this study, experimenters walked door-to-door to contact people who lived in two-person households. Each of these households was randomly assigned to receive a “treatment” or a “control” message. In the treatment, the experimenter encouraged the person who answered the door to vote at an upcoming election. In the control, the experimenter encouraged the practice of recycling. Nickerson noted who came to the door to speak to the experimenter, and then waited until after the election to look up who had voted and who had not.

Voter-contact studies are very common, and it is well established that get-out-the-vote campaigns actually work. So it was not surprising that the people in Denver and Minneapolis who answered the door and heard the plea to vote were about 10 percent more likely to turn out than those who heard the plea to recycle. The big surprise, however, was in the behavior of the people who did not answer the door. As it turns out, the other person in the household was about 6 percent more likely to vote. In other words, 60 percent of the effect on the person who answered the door was passed on to the person who did not answer the door.

Consider for a moment how these indirect effects might flow through a whole network. Nickerson’s creative study showed that a single plea to vote can change political behavior and spread from the experimenter to the person who heard the get-out-the-vote message to a person who neither heard the message nor met the experimenter. But why would it stop there? The person who didn’t answer the door might pass the effect on to her other friends and family as well. The effect probably won’t be as strong when it gets passed along; as in the game of telephone, the get-out-the-vote message might get diluted along the way as it passes from person to person to person. But suppose that the effect decreases the same way between every pair of people, going from a full effect to 60 percent at every step. If the first person is 10 percent more likely to vote and the second person is 6 percent more likely to vote, then the third person would be 3.6 percent more likely to vote, the fourth person would be 2.16 percent more likely to vote, and so on.

That may not seem like much change, but remember that while the size of the contagious effect decreases at each step, the number of people affected increases exponentially at each step. In a world where every friend has only two other friends, there might be only two people who become 10 percent more likely to vote, but there will be four more who are 6 percent more likely, 8 who are 3.6 percent more likely, sixteen who are 2.16 percent more likely, and so on. Add all those up for a city about the size of Denver or Minneapolis, and the result is that a single appeal to vote could cause about thirty extra people to go to the polls. And if you make an appeal to about three dozen people, suddenly you can get an extra thousand to go to the polls.

Of course, in real social networks, we tend to have more than two friends, and this increases the number of people who are close enough to us to be strongly affected by our actions. Yet, as we have noted, many of our friends already know one another, which means the effect might bounce around between the same people and never reach others who are socially distant from us. Also, the message may decay more rapidly than Nickerson found. It’s hard to say which of these features of real-world social networks would dominate, but Nickerson’s study gives us a taste of the potentially large cascade that could result from our personal decision to cast a vote.

So where do these results leave us on the question of why people vote? The existence of turnout cascades suggests that rational models of voting like those proposed by Anthony Downs, William Riker, and others have underestimated the benefit of voting. Instead of each of us having only one vote, we effectively have several and are therefore much more likely to have an influence on the outcome of an election. And the fact that one person can influence so many others may help to explain why some people have such strong feelings of civic duty. Establishing a norm of voting with our acquaintances is one way to influence them to go to the polls. People who do not assert such a duty miss the chance to influence people who share similar views, and this tends to lead to worse outcomes for their favorite candidates. In large electorates, the net impact on the result might be too marginal to create a dynamic that would favor people who assert a duty to vote. However, as Alexis de Tocqueville noted almost two hundred years ago, the civic duty to vote originated in much smaller political settings, such as town meetings, where changing the participation behavior of a few people would have made a big difference.18 Actually, as we will see in chapter 7, social collaboration has an even more ancient origin.

And the norm of voting appears so deep-seated that many people are dishonest when they talk to pollsters. Typically, about 20 to 30 percent of the people who say they voted in an election actually did not. How do we know this? The ballot in America is secret, but whether or not you showed up to cast a ballot is a matter of public record, so we have excellent official information about who voted and who did not. The problem of overreporting voter turnout is very well known among political scientists and a common subject in college classrooms.19 One of our favorite moments in Poli Sci 101 occurs when we ask our students to raise their hands if they did not vote. Typically, less than a quarter raise their hands. Yet, these are the honest ones, since we know from voter records that probably more than half the class did not vote.

Why do people lie about this? One possibility is that they fear social sanctions. Another is that they believe others are influenced by their political actions. Consider what happens if you tell everyone you are voting, but you stay home instead. On average, your actions will increase turnout even though you did not vote yourself. Moreover, since most of the people who decide to vote are likely to share your ideology, you can increase the vote margin for your favorite candidates without actually going to the polls. So now we have an explanation for why people might lie about voting as well. But, most important, we have an essential explanation for why people vote: they are connected, and it is rational for them to vote precisely because of their connections.

Voters are not the only political actors influenced by their social networks. If anything, the networks of politicians, lobbyists, activists, and bureaucrats are even more critical for determining how we govern ourselves. In fact, we want our political representatives to be well connected so they can influence others. And, indeed, politicians typically advertise their relationships with other important people. Every handshake is meticulously photographed, and many campaigns feature images of the candidate consorting with the powerful and the wealthy to make the point that this is a person who has the ability to get things done.

However, voters also worry that their representatives are connected to the wrong kinds of people. In the wake of the U.S. Congress influence-peddling scandal that erupted in late 2005, lobbyist Jack Abramoff was accused of buying votes and was widely described by the press as the “best-connected” lobbyist on Capitol Hill. President George W. Bush and other politicians like House Speaker Dennis Hastert and Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist feared the extent to which they could be “connected” to Abramoff, prompting them to return campaign donations and deny having spent time with him. They even curtailed contacts with other lobbyists to avoid the appearance that they were in some way influenced by lobbyists and legislators who had been tainted by the scandal.

Here we have a problem that we did not have with voters. Politicians know they are being watched, so they have an incentive to misrepresent their social networks. They might show a picture of a meeting with the president, but the president might have no idea who they are. They might hide a relationship with a powerful lobbyist or a steamy intern until they are forced to admit it under oath. And they might choose their friends (and even their spouses) in order to win elections. In other words, successful politicians tend to manipulate their networks for political advantage. This makes it nearly impossible to use the same methods to study politicians that we used to study voters. If we want to know who a voter’s friends are, we just ask them; they have very little reason to lie. If we want to know a politician’s connections, we need to use a little more ingenuity.

Although legislators do not broadcast lists of their enemies and friends, they do leave an enormous paper trail that we can study for clues. Some of the earliest attempts to discover relationships between politicians defined a connection as frequency of agreement on roll-call votes. The idea is that if Democrats Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama always vote “aye” on exactly the same bills, then maybe that means they are connected and that they might possibly be friends. However, agreement might also just mean these legislators have the same opinions about what laws should be passed. Clinton and Obama may both vote for a health-care bill they like, but they still might refuse to talk to each other. So roll-call votes might be more about ideology than personal relationships. Political scientists Keith Poole and Howard Rosenthal have developed highly sophisticated techniques that show that voting records can be used to place politicians on a liberal-conservative scale.20 They find that the ideological divide between Democrats and Republicans is huge and growing, but this does not necessarily imply a friendship divide. If we relied on roll-call votes to try to discover the social network between senators and representatives, we would have missed countless cross-party connections that we know exist, like the close friendship between Democrat Patrick Leahy and now former Republican Arlen Specter.

Instead of roll calls, we decided to look at a different activity. Whenever a bill is introduced in the House or Senate, the person who introduces it is called the “sponsor.” Legislators then have an opportunity to express support for it by signing on as a “cosponsor.” Sponsors tend to spend a lot of time recruiting cosponsors by making appeals to other legislators in person and in “Dear Colleague” letters. They do this not only because it increases the chance the bill will be passed but also because it helps them win elections. They also frequently refer to the cosponsorships they have received in floor debate, public discussion, letters to constituents, and campaigns. For example, when then-Senator Barack Obama tried to persuade fellow members of the Senate to pass his bill on government transparency, he noted the bill had been “cosponsored by more than forty of our colleagues.”21

The act of cosponsorship contains important information about the social network between legislators. In some cases, cosponsors actually help write or promote legislation, which is clearly a sign that the sponsor and cosponsor have spent time together and established a working relationship. In other cases, cosponsors merely sign on to legislation they support. Although it is possible that this can happen even when there is no personal connection between the sponsor and the cosponsor, it is likely that legislators make their decisions, at least in part, based on the personal relationships they have with the sponsoring legislators. The closer the relationship, the more likely it is that the sponsor has directly petitioned the cosponsor for support. It is also more likely that the cosponsor will trust the sponsor or owe the sponsor a favor, both of which increase the likelihood that the cosponsor will sign the bill. Thus, on average, cosponsorship patterns are a good way to measure the social connections between legislators.

Our cosponsorship network project was one of the first in political science to take advantage of the new era of large-scale data collection.22 The Library of Congress regularly keeps tabs on bills in the Congress, so we had access to more than 280,000 pieces of legislation proposed in the U.S. House and Senate since 1973, and these bills involved roughly 84 million cosponsorship decisions. There are many ways to use these data to measure how much total support a legislator receives from other members of Congress. The simplest is to count the total number of cosponsorships each legislator receives. If politicians are more influential, they should be better at getting their colleagues to support their bills.

Interestingly, the very first time we used this objective method for measuring influence, the legislator who turned out to be most influential was more corrupt than charismatic. The representative who received the most support during the 2003–2004 session of the House was Randy “Duke” Cunningham, a representative from Southern California who, according to the Washington Post, was involved in “the most brazen bribery conspiracy in modern congressional history.”23 Cunningham sold his house to defense contractor Mitchell Wade, who paid much more than the property was worth (Wade quickly resold the house at a loss of $700,000). Shortly thereafter, Wade began to receive defense contracts worth millions. Cunningham also lived on a yacht owned by Wade, and, according to the Wall Street Journal, he was provided with prostitutes, hotel rooms, and limousines in exchange for defense contracts. He eventually pleaded guilty to tax evasion, conspiracy to commit bribery, mail fraud, and wire fraud in federal court, where he was sentenced to one hundred months in prison (the longest sentence ever handed down to a former U.S. congressman).

Another interesting feature of the data was the degree of mutual support. If cosponsorships were really saying something about personal relationships, then we would expect to see a lot of reciprocity (“You scratch my back, and I’ll scratch yours”). Here, we measured the number of times one legislator cosponsored another and then compared that to the number of times the sponsor returned the favor. Not surprisingly, the rate of mutual cosponsorship was quite high, especially in the “good ol’ boys” network of the Senate, and the pattern has remained very consistent since the early 1970s.

Since cosponsorships indicate how well two people work together, we can also use them to say something about the network as a whole. Consider the observation that Americans have become increasingly polarized between Democrats and Republicans during the past few years. If that is really true, then, over time, we ought to see fewer cosponsor/sponsor relationships that cross party lines compared to the relationships that stay within party lines.

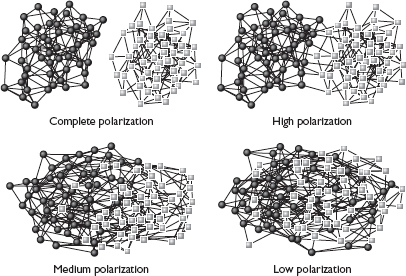

Imagine a network in which Democrats only work with other Democrats, and Republicans only work with other Republicans. The illustration shows Democrats and Republicans as two completely separate communities, or modules. Now suppose a few Democrats start crossing the aisle, or vice versa. This network would be less modular; it would be less obvious that there are two clearly defined groups that tend not to work together. In the extreme case where Democrats work with Republicans as often as they work with other Democrats and vice versa, the picture would look like one big network and it would not be possible to identify any modules at all. So the more modular the network is, the more polarized it is.

Hypothetical networks of one hundred U.S. senators reveal how polarized they can be. Black circles indicate Democrats, white squares indicate Republicans, and the lines between them indicate collaborative relationships.

Physicist Mark Newman has developed some ingenious algorithms to measure modularity and find coherent communities in social networks, and in our own research we used one of these to see how polarization in the U.S. House and Senate has changed over time.24 The results showed a sharp increase in the late 1980s and early 1990s, but then it leveled off. Some people blame House Speaker Newt Gingrich and the “Republican Revolution” for the dramatic rise in polarization. He and fellow Republicans Tom DeLay and Bill Frist swept to victory with their “Contract with America” in 1994, upset the seniority system in order to give Republican freshmen more power on committees, and worked to consolidate Republican districts in Texas and other states to maintain control of the House of Representatives. However, the network analysis shows that polarization started to increase sharply well before 1994. Republicans may have contributed to partisan breakdown, but evidence from the social network suggests that the change in leadership in 1994 was part of a broader trend toward a more polarized political system.

Although we are highly polarized in America, we are no more likely to remain that way than we are to be unhappy or overweight. Knowledge is power, and knowing what the network is doing is the first step toward solving potential problems. If scientists had been able to track polarization in the cosponsorship network back in 1990 and 1992, perhaps American citizens would have received early warning of the changes that were taking place in the legislative social network, and perhaps it might have been possible to make a better effort to head off some of the more vicious battles that would mar the political landscape in the coming decade—to the extent that network factors were responsible. For example, perhaps the Democratic leadership in 1992 would have worked harder to cross the aisle if they had known doing so would prevent the large-scale changes to the American political system that would lead to their twelve-year exile from power.

Social-network theorists have described a variety of ways to use information about social ties to measure the relative importance of group members. But none of these measures takes advantage of one other piece of information available here: the strength of the relationship between legislators.

Counterintuitively, the best bills in Congress for measuring social relationships are the ones that receive the least support. Why? Because bills with many cosponsors (sometimes called “Mom and Apple Pie” bills by political scientists) are frequently supported by legislators who had no contact with the sponsor. For example, ninety-nine senators signed Ted Kennedy’s bill “honoring the sacrifice of members of the United States Armed Forces who have been killed in Iraq and Afghanistan.” In contrast, bills with just a few cosponsors signal that the sponsor and cosponsor worked together or knew each other well. For example, in 2003, Representative Edward Schrock from Virginia was the sole cosponsor on a bill sponsored by Todd Akin from Missouri. A brief visit to their personal websites revealed that Schrock and Akin worked together on the House Committee on Small Business, and each mentioned his collaborative relationship with the other.

We thus used signatures on bills with few cosponsors to infer connections between legislators and to draw the network of supporting relationships. When we examined this network, we found confirmation of the adage “where you stand depends on where you sit.” People who are officially supposed to work together tend to be close, even if they are from different parties. The majority and minority leaders often had very strong relationships (like Republican Bill Frist and Democrat Tom Daschle), as did committee chairs and their cross-aisle counterparts (like Republican Bob Ney and Democrat John Larson). We also found strong relationships between people from the same state or from neighboring districts (like representatives Jim DeMint from South Carolina and Sue Myrick from North Carolina). But sometimes closeness to members of the other party can be an early warning signal of a party switch. Republican Senator Arlen Specter from Pennsylvania was so deeply embedded in relationships with Democrats in 2007 and 2008 that we originally thought we might have made a mistake in assigning his party when preparing the data. But, as it turns out, the network was just telling us that there was a good chance he would soon cross the aisle, which he did in early 2009.

We uncovered personal relationships too. For example, there was no official or geographic relationship between Senators John McCain and Phil Gramm, and their voting records differed on several important points. But the network of cosponsorships suggested they were very close in 2001 and 2002. And, as it turns out, McCain chaired Gramm’s 1996 presidential campaign, and McCain has also publicly discussed his close friendship with Gramm, which started in 1982 when they served together in the House.25 So there it was. The paper trail seemed to be leading to the very network we sought to discover.

Conversely, the network of cosponsorships also can be used to find personal enemies. Some representatives may have similar ideologies but nevertheless personal animosity—perhaps owing to a failed business dealing, a sexual indiscretion, or some other personal conflict. The feud between Democratic New Jersey Senators Frank Lautenberg and Bob Torricelli is legendary. At a closed-door caucus meeting of Senate Democrats held in 1999, Lautenberg chastised Torricelli for telling a reporter that he felt closer to Christie Todd Whitman (the Republican New Jersey governor) than his fellow Democratic senator. Torricelli became so enraged that he stood up and indecorously screamed, “You’re a fucking piece of shit, and I’m going to cut your balls off!”26 Not surprisingly, Torricelli and Lautenberg very rarely cosponsored each other’s bills, in spite of their close ideological and geographic affiliations.

The network of cosponsorships allows us to see how well connected each legislator is to the other legislators in the network. The legislators at the center of this network read like a who’s who of American politics, including Tom DeLay, Bob Dole, Jesse Helms, John Kerry, and Ted Kennedy. Without any specific information about these legislators other than their bill cosponsorship, the network reveals which individuals are most influential and which are more likely to run for higher office (our most recent top twenty list included Hillary Clinton, Ron Paul, Tom Tancredo, and Dennis Kucinich). And when we look at all the data, the very highest scoring legislator is John McCain, who was the 2008 Republican nominee for the presidency.

But the point of all this ranking and naming of names is not merely to arbitrate a contest about which cat is fattest. The reason we built the network and looked closely at the people at the center was to test the validity of our argument that the structure of a network matters. On its face, the network seems to identify party leaders, committee chairs, and other well-connected people. Legislators who are able to elicit support in the cosponsorship network because they are broadly connected or well connected to other important legislators ought to be better able to shape the policies that emerge from their chamber. And in fact, they are.27 In the House, members in the center of the cosponsorship network passed three times as many amendments as those on the periphery. In the Senate, the difference was even greater; highly connected senators passed seven times as many amendments.

Being well connected in the social network makes a huge difference when it comes to shaping bills as they move through the legislative process. However, this tells us nothing about the success of those bills. Senators and members of the House can add all the amendments they want, but if the bill fails final passage, all is for naught. To what extent does connectedness influence the outcome of final votes on the floor? If better-connected legislators are indeed more influential, then they should be able to recruit more votes for the bills they sponsor. Otherwise, what is the point of being well connected in the first place?

When we looked at the effect of social-network position on roll-call votes, we found that the best-connected representatives were able to garner ten more votes than average (out of 435 representatives), while the best-connected senators were able to garner sixteen more (out of 100 senators). That may not seem like much, but consider how close many of these roll-call votes are. Changing the connectedness of the sponsor of a bill from average to very high would change the final passage outcome in 16 percent of the House votes and 20 percent of the Senate votes. In other words, if a bill is introduced by a person in the middle of the network, it would pass; but if the same bill were introduced by someone just outside of the middle, it would fail. Connectedness matters.

In addition to voters and politicians, lobbyists and activists also live in social networks that have a big impact on their effectiveness. It is well known that lobbyists tend to spend time with legislators with similar policy preferences, making us wonder what exactly it is that lobbyists accomplish. After all, a Haliburton lobbyist is not going to change Dick Cheney’s mind any more than a Sierra Club representative will change Al Gore’s. That’s just preaching to the choir. The popular image of lobbyists is that they are engaged in influence, but instead it seems like they spend more time engaging in homophily, flocking together with birds of a feather.

Political scientists Dan Carpenter, Kevin Esterling, and David Lazer carefully studied the social networks of energy and health care lobbyists and found a much more nuanced story.28 While it is true that lobbyists tend to develop strong ties with their ideologically similar counterparts in the government, their success is influenced by the network as a whole. For example, lobbyists are much more likely to communicate with one another if their relationship is brokered by a third party. Also, lobbyists are more likely to be granted access to key players in the government if they are connected to someone who already has access. So the greater the number of friends they have who already have access, the better. What this means is that the most successful lobbyists will be those who have the most weak ties, that is, the most friends of friends walking the halls of power. Strong ties help, but weak ties help more because they greatly expand the total number of potential connections. Just like job seekers tapping their weak ties (in chapter 5), searching for influence is easier with a broad network. In fact, Carpenter and his colleagues found that the number of strong ties has almost no impact on whether a lobbyist will be given access. Since each new weak tie can lead to multiple others, this sets up a rich-get-richer dynamic that generates rising stars like Jack Abramoff and helps to explain why corruption is so widespread.

While lobbyists are firmly embedded within the political system, the same is not always true for activists. Abbie Hoffman—member of the “Chicago Seven” and cofounder of a 1960s activist group called the Youth International Party (the “yippies”)—encouraged his followers to work against the system and showed them how to grow marijuana, steal credit cards, and make pipe bombs.29 American social movements are often bitterly divided over the question of whether to work for change within the system or outside it. Political scientists Michael Heaney and Fabio Rojas were interested in finding out why some worked within and others worked without, and not surprisingly they found that social networks played a critical role.

As the movement against the Iraq War was heating up in 2004 to 2005, Heaney and Rojas collected information from 2,529 activists at several events, including a 500,000-person protest outside the Republican National Convention in New York City on August 29, 2004; a protest of George W. Bush’s second inauguration in Washington, DC, on January 20, 2005; antiwar rallies in New York City, Washington, DC, Fayetteville, NC, Indianapolis, Chicago, San Diego, and San Francisco, commemorating the second anniversary of the Iraq War on March 19 and March 20, 2005; May Day rallies held in New York City on May 1, 2005; and the 300,000-person antiwar protest in Washington, DC, on September 24, 2005.30 Each of the activists provided basic information about why they were protesting and named organizations that had contacted them to attend the rally. This gave the researchers an incredibly detailed picture of the overall network of interactions and allowed them to make two important conclusions.

First, whether they admit it or not, activists’ behavior is shaped by differing partisan attitudes, because they tend to join organizations with others who share their party affiliation. The “party in the street” may think of itself as quite disconnected from the type of formal party that runs the government, but it ends up attracting people who all have the same partisan ideologies. Second, and not surprisingly, activists who are more central to the network of political groups are more likely to work within the system, embracing institutional tactics like lobbying instead of civil disobedience. So people who think of themselves as Democrats might join the Sierra Club, but they are very unlikely to join less established groups such as the yippies that might be pursuing the same goal with different methods.

When we first published the results of our voting model, a number of online activists became very interested in the idea that voting is contagious. In particular, GROWdems.com contacted us early on to include our research in an e-book they created to improve their get-out-the-vote efforts. They believed that knowing that one extra vote leads to many others would give volunteers a greater sense of purpose and effectiveness, which could motivate more people to help with their campaign. An online group at CircleVoting.com also started using our research to encourage people to reach out to their online social networks to get them to the polls.

But these efforts are just the tip of the iceberg. The Obama campaign’s use of Internet and mobile technology shows the real power of online social networks. They took advantage of social media like YouTube for free advertising. Internet users watched a stunning 14.5 million hours of official campaign ads online. For comparison, it would have cost about $47 million to buy that much advertising time on broadcast TV. They also used YouTube to combat negative stories. When Obama’s former pastor, Reverend Jeremiah Wright, made the news with his “God Damn America” sermon, the traditional media latched on to the story and covered it for several days. Meanwhile, supporters forwarded links to Obama’s own speech on race, which made it hard to believe that he shared Wright’s views. During the primaries alone, 6.7 million people watched Obama’s thirty-seven-minute speech on YouTube.

Other candidates also tried to organize their supporters online, but with less success. The Pew Research Center reported that Obama supporters were more likely than Clinton supporters to watch campaign speeches and announcements, campaign commercials, interviews with the candidates, and televised debates online. They were also more likely to donate money online.31

Activists around the world are also starting to use the Internet to organize vast demonstrations. For example, in January 2008, Oscar Morales, a thirty-three-year-old engineer from Barranquilla on Colombia’s Caribbean coast, mobilized millions of people by using his social network. On the social networking site Facebook, he started a group composed of himself and five friends (Hector, Juan, Miguel, Maritza, and Gabo) protesting the holding of hostages by the military group FARC (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia). Morales’s group, called “No More,” grew to include 272,578 online members within a month. Invitations to real-life marches spread through cyberspace, and the intensity built over weeks. Finally, on February 4, 2008, as planned, millions of people in countries around the world marched to protest the taking and keeping of hostages: 4.8 million people turned out in nearly four hundred events in Colombia, as well as hundreds of thousands of others in countries ranging from neighboring Venezuela to faraway Sweden, Spain, Mexico, Argentina, France, and the United States.32

The Colombia demonstrations illustrate the power of online social networks to magnify whatever they are seeded with. One person started a campaign that touched millions. But online activism started long before the Obama campaign and the advent of Facebook. In the early days of the Internet, people like Glen Barry used the new technology to write about and promote political causes. Barry’s “Gaia’s Forest Conservation Archives” was an online diary that commented on current events related to the environment and urged the government to preserve forests as early as 1993 (it can still be found online). Soon afterward, a variety of people were promoting many different causes in their web logs, or blogs, and the blogosphere was born.

Because information was so easy to transmit on the Internet, some people believed that the blogosphere might bring us closer together politically. The hope was that we would discuss issues of the day in a nearly ideal Jeffersonian form of democratic exchange. But Lada Adamic, a physicist at the University of Michigan, has produced some stunning images of these exchanges that show nothing could be further from the truth.33 In plate 6 we reproduce her image, from the 2004 election, of the network of A-list bloggers from the Left and Right, including well-known sites like Daily Kos, Andrew Sullivan, Instapundit, and RealClearPolitics. Conservative blogs are red, as are links between them, whereas liberal blogs and links are blue.

What immediately stands out is the extreme separation between liberals and conservatives. If the hope for the Internet was that these two groups would talk to each other, the blog network reveals that these hopes have been utterly dashed. Just like the real-world political networks studied by Lazarsfeld and Berelson and later by Huckfeldt and Sprague, the online social network appears to be strongly homophilous and polarized. This suggests that political information is used more to reinforce preexisting opinions than to exchange differing points of view. Adamic used a procedure to detect “communities” in the network (similar to Newman’s modularity procedure that we used for our cosponsorship work). Communities were defined as a group of blogs that were more closely connected to one another than to the rest of the network. She found that the conservative bloggers were much more densely connected to one another within their “community” than the liberal bloggers were, suggesting that the reinforcement effect is even stronger on the Right than on the Left. But even though liberals may tend to seek out opposing points of view more often, the dramatic separation shows that, like conservatives, they still stick very closely to the ideas and facts they know.

In this example, there may not be much communication between people who support and oppose the government, but at least an opposition party is allowed to exist. Researchers at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard Law School have extended Adamic’s research to other countries in order to see whether their blogospheres follow similar patterns. The first country examined was Iran, where they collected daily information for seven months from nearly one hundred thousand Persian language blogs.34 As part of the Internet and Democracy project, John Kelly and Bruce Etling were very interested in whether the blogosphere had a personal impact on freedom of speech or a more global impact on Iran’s prospects for liberalizing their form of government. Given Iran’s reputation for political repression, they expected to find a tightly controlled and repressive political discourse. But instead they found a network of blogs that was not much different from those found in the free world.

Plate 7 shows a map of the Iranian blogosphere. There are so many links that they are suppressed here to make it is easier to see what is going on. Once again, the larger nodes are the more important blogs (as measured by the number of links to the blog), but in contrast to plate 6 (the U.S. blogosphere map that showed only political blogs), here there are several “communities” that focus both on political and nonpolitical topics. As Kelly and Etling note: “Iranian bloggers include members of Hezbollah, teenagers in Tehran, retirees in Los Angeles, religious students in Qom, dissident journalists who left Iran a few years ago, exiles who left thirty years ago, current members of the Majlis (parliament), reformist politicians, a multitude of poets, and quite famously the president of Iran, among many others.”35

The Iranian blogosphere divides into four more or less coherent communities that can be described by the content of their blogs. Two of these have little to do with politics or public affairs. One focuses mainly on poetry and Persian literature, and the other is a hodgepodge of special interests and popular topics (related to celebrities, sports, and minority cultures). But the other two groups are explicitly political.

The first political group is composed of two closely overlapping communities: a reformist politics community of internal dissidents and a secular/expatriate community that is made up of notable dissidents and journalists who left Iran and are living abroad. They tend to discuss women’s rights, political prisoners, and current affairs, including political problems in Iran such as drug abuse and environmental degradation. Since much of this discussion is critical of the government, it is somewhat surprising that most bloggers use their own names rather than pseudonyms. A second political group, made up of conservatives and religious youth, blogs about their support of the Iranian Revolution and the government’s Islamist political philosophy. One notable community in this group is the Twelvers sect that believes that Muhammad ibn Hasan ibn Ali (the 12th Imam) will return to save mankind and create a perfect society before a final day of resurrection. But this is not simply a bunch of yes-men: many of the conservatives in this group actually attack the government for being too corrupt or too lenient.

Notice that two of Iran’s presidents have popular blogs. President Ahmadinejad is part of the conservative group, and his predecessor President Khatami is part of the reformist group, but both blogs are positioned near the center of the blogosphere since they tend to get referenced by blogs from a variety of communities. Their positions indicate that they sit on a number of paths from one community to another, acting like the “weak tie” bridges that characterize successful lobbyists and politicians in the United States.

In fact, the Iranian blogosphere looks quite a bit like the U.S. blogosphere, which is puzzling. How could an illiberal regime permit such a wide range of seemingly democratic discourse? The Iranian government does block access to several websites, but less than 20 percent of the reformist blogs are affected, and hardly any of the conservative blogs are affected, even those that are highly critical. This suggests that the government either cannot or will not shut down the discourse. It is hard to believe that the regime lacks will, given its record of shutting down traditional media sources (such as opposition newspapers) and jailing (or worse) the people who run them. But if so, then maybe the ability to relocate democratic social networks and the resulting flow of information to an online environment can thwart the government’s attempts to disrupt these networks, control information, and prevent the self-organization of a political opposition. Indeed, in June 2009, the media was proclaiming a “Twitter revolution” in Iran as citizens used the Twitter microblogging service to disseminate information across online network ties and to organize against what seemed like a rigged election. But only time will tell if the Iranian blogosphere will have a liberalizing effect on the government there.

This suggests that changes in technology may be altering the way we live in our social networks and may have profound effects on the way we govern ourselves. We have already seen that real-world social networks can be used to spread information and enhance the ability of well-connected people to achieve their goals. In the next two chapters, we will look more closely at the nature and origin of our desire to connect and how technology may be changing the way we do so. In a certain sense, we live in a brand-new world. Our social networks are ever faster and larger as we text, e-mail, Twitter, Facebook, and MySpace all the people we know (and even people we don’t). And this new world certainly gives us a bird’s-eye view of the social networks in which we live, making us more conscious than ever of the importance of being connected. But it also seems to us that these networks were ready-made to be put online. We have lived in them for millions of years. Our ancestors prepared us to live in them. Networks are under our skin. And before we think about where we are going, it will be useful to pause and reflect on where we have been.