Babylon, the first city to be built after the great mythical flood, was one in which, the book of Genesis tells us, humanity was united: “And the Lord said, ‘Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language… and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do.’ ”1 And the first thing that the unrestrained residents of Babylon imagined to do was to build a tower so immense that it would reach the heavens. Genesis recounts that God punished the people by destroying the tower, giving them multiple languages, and scattering them across the earth. This story illustrates the folly of hubris, and we usually focus on the polyglot consequences. Often overlooked, however, is the fact that the Babylonians were punished not so much by being given different languages but, rather, by becoming disconnected from one another.

By banding together, the citizens had been able to do something—build the tower—that they could not have done alone. Other stories from the Bible allude to the power of connections but put a more positive spin on what connected humans can do. When Joshua and the Israelites arrived at the gates of Jericho, they found that the walls of the city were too steep for any one person to climb or destroy. And then, the story goes, God told them to stand together and march around the city. When they heard the sound of the ram’s horn, they “spoke with one voice”—in a kind of synchronization like La Ola—and the walls of Jericho came tumbling down.

Observations about connection and its implications are ancient, in no small part because theologians and philosophers, like modern biologists and social scientists, have always known that social connections are key to our humanity—full of both promise and danger. Connections were often seen as what distinguished us from animals or an uncivilized state.

In 1651, the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes engaged in a thought experiment in which he described the prototypic condition of human existence. In a “state of nature,” he supposed in his famous work The Leviathan, there is bellum omnium contra omnes, a “war of all against all.” There is anarchy. It is, in fact, Hobbes who observed that the “life of man [is] solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”2 Hobbes’s use of solitary—which is often, unaccountably, clipped from the phrase—suggests that a disconnected life is full of woe.

Given these grim circumstances, Hobbes theorized, people would have chosen to enter into a “social contract,” sacrificing some of their liberty in exchange for safety. At the core of a civilized society, he argued, people would form connections with one another. These connections would help curb violence and be a source of comfort, peace, and order. People would cease to be loners and become cooperators. A century later, the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau advanced similar arguments, contending in The Social Contract that the state of nature was indeed brutish, devoid of morals or laws, and full of competition and aggression. It was a desire for safety from the threats of others that encouraged people to band together to form a collective presence.

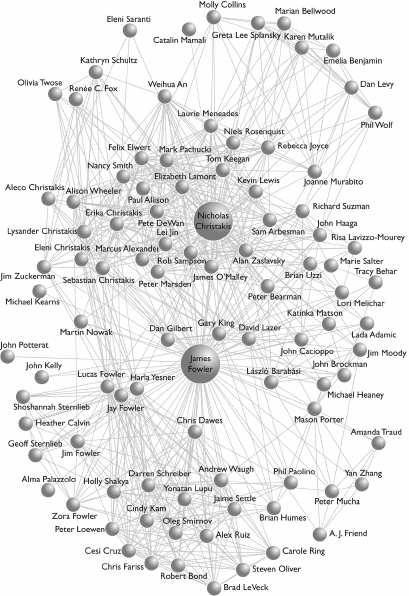

This progression of human beings out of such an ostensibly anarchical condition into ever larger and ever more ordered aggregations—of bands, villages, cities, and states—can in fact be understood as a gradual rise in the size and complexity of social networks. And today this process is continuing to unfold as we become hyperconnected.

The networks we create have lives of their own. They grow, change, reproduce, survive, and die. Things flow and move within them. A social network is a kind of human superorganism, with an anatomy and a physiology—a structure and a function—of its own. From bucket brigades to blogospheres, the human superorganism does what no person could do alone. Our local contributions to the human social network have global consequences that touch the lives of thousands every day and help us to achieve much more than the building of towers or the destruction of walls.

A colony of ants is the prototypic superorganism, with properties not apparent in the ants themselves, properties that arise from the interactions and cooperation of the ants.3 By joining together, ants create something that transcends the individual: complex anthills spring up like miniature towers of Babylon, tempting wanton children to action. The single ant that finds its way to a sugar bowl far from its nest is like an astronaut stepping foot on the moon: both achievements are made possible by the coordinated efforts and communication of many individuals. Yet, in a way, these solitary individuals—ant and astronaut, both parts of a superorganism—are no different from the tentacle of an octopus sent out to probe a hidden crevice.

In fact, cells within multicellular organisms can be understood in much the same way. Working together, cells generate a higher form of life that is entirely different from the internal workings of a single cell. For example, our digestion is not a function of any one cell or even one type of cells. Likewise, our thoughts are not located in a given neuron; they arise from the pattern of connections between neurons. Whether cells, ants, or humans, new properties of a group can emerge from the interactions of individuals. And cooperative interactions are hallmarks of most major evolutionary leaps that have occurred since the origin of life—consider the incorporation of mitochondria into eukaryotic cells, the agglomeration of single-cell organisms into multicellular organisms, and the assembly of individuals into superorganisms.4

Social networks can manifest a kind of intelligence that augments or complements individual intelligence, the way an ant colony is “intelligent” even if individual ants are not, or the way flocks of birds determine where to fly by combining the desires of each bird.5 Social networks can capture and contain information that is transmitted across people and time (like norms of trust, traditions of reciprocity, oral histories, or online wikis) and can perform computations that aggregate millions of decisions (such as setting a market price for a product or choosing the best candidate in an election). And networks can have this effect regardless of the intelligence of the individual members. Consider, for example, that the way humans laid a rail network throughout England in the twentieth century resembles the way fungi (another species that forms superorganisms) collaboratively explore a patch of ground in the forest in order to exploit and transport resources by creating a network of tubes.6 Fungi can even “collaborate” to find the best path through mazes into which they have been placed by human experimenters.7

Social networks also have a memory of their own structure (staying intact even if people come and go) and their own function (preserving a culture even when people come and go). For example, if you join a trusting network of people, you benefit from that trust and are shaped by it. In many cases, it is not just that the people in your network are more trusting, or even that their trusting behavior engenders trust in you; rather, the network facilitates this trust and changes the way individuals behave.

Like living creatures, networks can be self-replicating. They can reproduce themselves across space and time. But unlike corporeal organisms, networks can, if disassembled, reassemble themselves at a distance. If every person has a memory of whom he or she is connected to, we can cut the connections and move all the people from one place to another, and the network will reappear. Knowledge of one’s own social ties means that the network can reemerge even though no single person knows how everyone else in the network is connected.

Networks are also self-replicating in the sense that they outlast their members: the network can endure even if the people within it change, just as cells replace themselves in our skin, computers are swapped out on a server farm, and new buyers and sellers come to a market that has been located in the same place for centuries. In one study of a network of four million people connected by their phone calls, researchers showed that, paradoxically, groups with more than fifteen interconnected people that experienced the greatest turnover endured the longest.8 Large social networks may in fact require such turnover to survive, just as cell renewal is required for our bodies to survive.

These observations highlight another amazing, organism-like property: social networks are often self-annealing. They can close up around their gaps, in the same way that the edges of a wound come together. One person might step out of a bucket brigade, but then the two people he was connected to will move closer to each other, forming a new connection to fill in the gap. As a result, water will continue to flow. In more complicated, real-life networks, it seems likely that the very purpose of redundant networks ties, and of transitivity, is precisely to make the networks tolerant of this kind of loss, as if human social networks were designed to last.

Like a worldwide nervous system, our networks allow us to send and receive messages to nearly every other person on the planet. As we become more hyperconnected, information circulates more efficiently, we interact more easily, and we manage more and different kinds of social connections every day. All of these changes make us, Homo dictyous, even more like a superorganism that acts with a common purpose. The ability of networks to create and sustain our collective goals continues to strengthen. And everything that now spreads from person to person will soon spread farther and faster, prompting new features to emerge as the scale of interactions increases.

The social networks we create are a valuable, shared resource. Social networks confer benefits. Alas, not all people are in the best position to capture these benefits, and this raises fundamental questions of justice and public policy.

Social scientists call such a shared resource a public good. A private good is one the owner can exclude others from consuming, and one that, once consumed, cannot be consumed again. If I own a cake, I can prevent anyone else from eating it, and once I eat it myself, there is none left for anyone else. A public good, in contrast, can be consumed without harming the interests of others, and without reducing others’ ability to use it. Think of a lighthouse. One ship making use of the light to avoid colliding with the rocks does not prevent another ship from doing the same. Public radio, Fourth of July fireworks, and municipal water fluoridation are other examples of public goods. Not all public goods are man-made, of course. Think of the air. One person breathing does not make anyone else have less air, nor does it prevent anyone else from breathing.

Other public goods are less tangible even than light or air. Think of civic duty. As Alexis de Tocqueville argued in the early nineteenth century, if everyone feels the obligation to maintain a civil society, to act in a trustworthy way, and to volunteer for the nation in times of attack, then all citizens can benefit from these traditions and norms. And the benefit to one person does not reduce the benefit for others.

But public goods are difficult to create and maintain. It often seems that no one has an incentive to care for them, as a breath of not-so-fresh air in any polluted city demonstrates. Hence, public goods often arise as by-products of the actions of individuals acting with some self-interest. A shipping company or port authority that builds a lighthouse to safeguard its own ships ends up safeguarding all ships.

Some public goods get better the more they are produced. A classic example of a particular kind of network good is a telephone or fax machine. The first person to get a fax machine finds that it is worthless because there is no one to fax anything to. However, as more and more people acquire fax machines, they become more and more valuable. A similar—if more abstract—example of a network public good is trust. As discussed in chapter 7, trust is most valuable when others are also trusting; and being trusting in a world of free riders is very painful. But many other human behaviors and beliefs increase in value in this way. For example, the positive effects of religiosity on well-being is higher in countries where average religiosity is higher.9 Like fax machines, religion is more useful if others also believe, in part because religion works to enhance well-being by fostering social ties.

The social networks that humans create are themselves public goods. Everyone chooses their own friends, but in the process an endlessly complex social network is created, and the network can become a resource that no one person controls but that all benefit from. From the point of view of each person in the network, there is no way to tell exactly what kind of world we inhabit, even though we help create it. We can see our own friends, family, neighbors, and coworkers, and perhaps we know a little bit about how they are tied to each other, but how we are connected to the network beyond our immediate social horizon is usually a mystery. Yet, as we have seen time and again, the precise structure of the network around us and the precise nature of the things flowing through it affect us all. We are like people on a crowded dance floor: we know that there are ten people pressed up against us, but we are not sure if we are in the middle or at the edge of the room or whether a wave of ecstasy or fear is spreading toward us.

Of course, not all networks create something that is useful, valuable, and shared, let alone something that is positive. When we say “good” we really just mean any old thing: pistols and poisons are goods too. And networks can function as conduits for pathogens or panic. Indeed, social networks can be exploited for bad ends. As we noted in chapter 1, violence spreads in networks, as does suicide, anger, fraud, fascism, and even accusations of witchcraft.

The interpersonal spread of criminal behavior is an illuminating example of a bad network outcome. One persistent mystery about crime is its variation across time (fluctuating from year to year) and space (varying in adjoining police precincts or jurisdictions). For example, in Ridgewood Village, New Jersey, there are 0.008 serious crimes per capita, whereas in nearby Atlantic City, there are 0.384—a nearly fiftyfold difference. This variation seems too great to be explained by some kind of disparity in the costs and benefits of crime, or even in observable features of the environment or the residents, such as the availability of after-school programs or educational attainment. So what explains the difference? Much evidence suggests that it is partially due to the reverberation of social interactions: as criminals act in a given place and time, they increase the likelihood that others nearby will commit crimes, so that even more crimes occur than would otherwise be expected.10 And the groups over which these effects extend can number in the hundreds.

A detailed study of these effects by economist Ed Glaeser and his colleagues also shows that certain crimes spread more easily than others, just as one would expect if social influences were more important than local socioeconomic conditions. People are much more likely to be influenced to steal a car when someone else does than to commit a burglary or robbery, and influence is even weaker for crimes like rape and arson. The riskier or more serious the crime, the less likely others are to follow suit (though there can be frenzies of murder too, as in the Rwandan genocide). Moreover, as a further illustration of the social nature of crime, nearly two-thirds of all criminals commit crimes in collaboration with someone else.11

While we are not aware of any experimental efforts to foster crime by exploiting social contagion, there have been experiments to study less extreme unethical behaviors. At Carnegie Mellon University, a group of students were asked to take a difficult math test. In the middle of the room, researchers placed a confederate who at some point visibly cheated on the test. When students witnessed the cheater’s behavior, they too began to cheat.12 Especially relevant, though, was the discovery that cheating only increased if the cheater was a person to whom the other students felt connected. If the cheater wore a plain T-shirt, students were more likely to cheat than if he wore a T-shirt from the University of Pittsburgh (Carnegie Mellon’s local rival institution).

In spite of these potential negative effects, we are all connected for a reason. The purpose of social networks is to transmit positive and desirable outcomes, whether joy, warnings about predators, or introductions to romantic partners. To some extent, the transmission of bad behaviors and other adverse phenomena (like germs) are merely side effects that we must endure in order to reap the benefits of networks; they are grafted onto an apparatus that was built, evolutionarily speaking, for another, more beneficial purpose.

To be clear, we are not suggesting a linear progression across history or evolutionary time from anarchy to state to utopia. But we do believe that there is a utopian impulse to form networks that has always been with us. We gain more than we lose by living within social networks, and this drives us to embed ourselves in the lives of others. The natural advantages of a connected life explain why social networks have persisted and why we have come to form a human superorganism.

Crucial traits and behaviors that lie at the root of—and that nourish—social connections have a genetic basis. Altruism, for example, is a key predicate for the formation and operation of social networks. If people never behaved altruistically, never reciprocated kind behavior, or, worse, were always violent, then social ties would dissolve, and the network around us would disintegrate. Some degree of altruism and reciprocity, and indeed some degree of positive emotions such as love and happiness, are therefore crucial for the emergence and endurance of social networks. Moreover, once networks are established, altruistic acts—from random acts of kindness to cascades of organ donation—can spread through them.

Charity is just one example of the goodness that flows through networks. About 89 percent of American households give to charity each year (the average annual contribution was $1,620 in 2001), and fund-raising efforts often seem designed to capitalize on processes of social influence and notions of community embeddedness. Appeals are commonly organized so that people you feel connected to rather than strangers call you to ask for money, such as graduates of your college or relatives of your friend with cancer (of course, it is cheaper to use such volunteers too). Bikeathons and walkathons are organized to engender a sense of community among those participating and to encourage direct contact between participants and the friends and neighbors who sponsor them. And organizations from hospitals to Boy Scout troops to small towns employ a kind of thermometer that is publicly displayed and that tracks charitable giving to their cause, implicitly saying, Look, all these other people gave money; now how about you? Indeed, surveys of people who have given money to diverse causes find that roughly 80 percent did so because they were asked to by someone they knew well.13

In one demonstration of the spread of prosocial norms, economist Katie Carman studied charitable giving (via payroll deductions to the United Way) in 2000 and 2001 among the seventy-five thousand employees in a large American bank operating in twenty states. She found that employees gave more when they worked next to generous colleagues. Carman acquired detailed information about the employees’ connections at work and their specific locations in bank offices. In a clever exploitation of the most mundane piece of information imaginable—the mail codes used to deliver letters and parcels to areas within bank buildings—she was able to identify groups of people ranging in size from one to 537, with a median size of just nineteen people. She studied what happened to employee giving if they were obliged to move from one location in the bank to another. She found that when people were transferred from a location where others did not give much money to a location where they did, every $1.00 increase in the average giving of their nearby coworkers resulted in a $0.53 increase in their own contribution.14 There are, of course, several possible mechanisms for this influence: one person could provide information about how to give, could pressure the other to give, or could simply act as a role model for giving.

While Carman’s work suggested the person-to-person spread of altruistic norms, our own experiments illustrate the surprising pay-it-forward properties of altruism. We know that if Jay is generous to Harla, Harla will be generous to Jay, but if Jay is generous to Harla, will Harla be generous to Lucas? We devised an experiment to evaluate the idea that altruism could spread from person to person to person. We recruited 120 students for a set of cooperation games that lasted five rounds. In each round, students were placed in groups of four, and we adjusted the composition of the groups so that no two students were ever in the same group twice. Students were each given some funds, and they could decide how much money to give to the group at a personal cost, and then at the end of each round we let them know what the others had done.

When we analyzed their behavior, we found that altruism tends to spread and that the benefits tend to be magnified. When one person gives an extra dollar in the first round, the people in her group each tend to give about twenty cents more in the second round, even though they have been placed in completely new and different groups! When a person has been treated well by someone, she goes on to treat others well in the future. And, even more strikingly, all the people in these new second-round groups are also affected in the third round, each giving about five cents more for every extra dollar that the generous person in the first round spent. Since each group contains three new people at every stage, this means that giving an extra dollar initially caused a total increase in giving by others of sixty cents in the second round and forty-five cents in the third. In other words, the social network acted like a matching grant, prompting an extra $1.05 in total future giving by others for each dollar a person initially chose to give.

Whether people behave altruistically is also determined by the structure of the social network. One ingenious experiment documented a “law of giving” at an all-girls school in Pasadena, California.15 The investigators asked seventy-six fifth- and sixth-grade girls to identify up to five friends; this allowed investigators to draw the girls’ social networks and ascertain which girls were each girl’s friends, friends of friends, friends of friends of friends, and so on. They had the girls play the dictator game discussed in chapter 7, and each girl was asked how much she would share from a $6 sum with each of ten other girls who were listed by name. The girls were most generous with their friends, and the amount given declined as social distance increased. On average, the girls offered their friends 52 percent of the $6, friends of friends 36 percent, and friends of friends of friends 16 percent. The best predictor of how much each girl gave was not any measured characteristic of either the givers or the recipients—such as whether either girl was tall or short, had many or few siblings, or wore glasses or braces. Instead, it was the degree of separation between the giver and the receiver.

This is one way that popularity is beneficial. If you are in the center of a social network, you are more likely to be one, two, or three degrees removed from many other people than if you were at the periphery of the network. Consequently, you can earn a centrality premium if good things (like money or respect) are flowing through the network. More people are willing to act altruistically toward you than toward those at the margins. When all the rounds of the game among the schoolgirls were completed, the most popular girls earned four times as much as the least popular. The ability of social networks to magnify whatever they are seeded with favors some people over others.

A pair of experiments with college undergraduates added a few wrinkles to these results.16 One elicited information about the close friends of 569 undergraduates residing in two large college dormitories in 2003. The other involved 2,360 students using Facebook in 2004. The students were less and less generous to people farther away in the network and were no more generous to people beyond three degrees of separation than they were to total strangers. The college students were also more likely to act altruistically, and to give generously, to social contacts with whom they shared many friends in common. Katrina is more likely to act altruistically toward Dave if they share Ronan and Maddox as friends than if they just share Ronan.

Moreover, the motivation to give to friends that subjects did not expect to interact with again was twice as strong as the motivation to give to strangers that subjects expected to have further interactions with. Put another way, we would rather give a gift to a friend who will never repay us than to give a gift to a stranger who will. The reason is that we give to sustain the network, and it is the network itself that we value. Our social ties repay us for our gifts. Generosity binds the network together, but the network also functions to foster and determine generosity.

This study of college students confirmed a final, crucial point: in real-life interactions, as predicted by the theoretical models discussed in chapter 7, cooperators tend to hang out with other cooperators, and there is homophily in the inclination to be altruistic. Altruistic and selfish undergraduates each had the same number of friends, on average. But altruistic people were embedded in networks of other altruistic people.

Today it is common to focus on inequalities in our society that appear to arise from race, income, gender, or geography. We pay attention to the fact that people with better education generally have better health or more economic opportunities, that whites may enjoy advantages that minorities do not, and that where people live affects their life prospects. Politicians, activists, philanthropists, and critics are driven by the recognition that we do not all appear to have equal access to societal goods and that the pattern of access is often manifestly unjust. In short, we live in a hierarchical society, and our sociodemographic characteristics stratify and divide us.

But there is an alternative way of understanding stratification and hierarchy that is based on how people are positioned with respect to their connections. Positional inequality occurs not because of who we are but because of who we are connected to. These connections affect where we come to be located in social networks, and they often matter more than our race, class, gender, or education. Some of us have more connections, and some fewer. Some of us are more centrally located, and some of us find ourselves at the periphery. Some of us have densely interconnected social ties and all our friends know one another, and some of us inhabit worlds where none of our friends get along. And these differences are not always of our own doing because our network position also depends on the choices that others around us make.

Not everyone can tap the public goods that are fostered and created by social networks. Your chance of dying after a heart attack may depend more on whether you have friends than on whether you are black or white. Your chance of finding a new job may have as much to do with the friends of your friends as with your skill set. And your chance of being treated kindly or altruistically depends on how well connected others around you are.

Social scientists and policy makers have neglected this kind of inequality, in part because it is so difficult to measure. We cannot understand positional inequality by just studying individuals or even groups. We cannot ask a person where he is located in the social network as easily as we can ask him how much money he earns. Instead, we must observe the social network as a whole before we can understand a person’s place in it. This is not a trivial problem. Thankfully, as discussed in chapter 8, the advent of digital communications (e-mail, mobile phones, social-network websites) is making it easier to see networks on a large scale without necessarily surveying individuals at great expense. Correlating people’s network centrality with their mortality risk, their transitivity with their prospects of repaying a loan, or their network position with their propensity to commit crimes or quit smoking offers new avenues for policy intervention.

But in an increasingly interconnected world, people with many ties may become even better connected while those with few ties may get left farther and farther behind. As a result, rewards may flow even more toward those with particular locations in social networks. This is the real digital divide. Network inequality creates and reinforces inequality of opportunity. In fact, the tendency of people with many connections to be connected to other people with many connections distinguishes social networks from neural, metabolic, mechanical, or other nonhuman networks. And the reverse holds true as well: those who are poorly connected usually have friends and family who are themselves disconnected from the larger network.

To address social disparities, then, we must recognize that our connections matter much more than the color of our skin or the size of our wallets. To address differences in education, health, or income, we must also address the personal connections of the people we are trying to help. To reduce crime, we need to optimize the kinds of connections potential criminals have—a challenging proposition since we sometimes need to detain criminals. To make smoking-cessation and weight-loss interventions more effective, we need to involve family, friends, and even friends of friends. To reduce poverty, we should focus not merely on monetary transfers or even technical training; we should help the poor form new relationships with other members of society. When we target the periphery of a network to help people reconnect, we help the whole fabric of society, not just any disadvantaged individuals at the fringe.

The old ways of understanding human behavior are not up to the task. One classic method used to understand collective human behavior examines the choices and actions of individuals. For instance, we can see markets, elections, and riots as mere by-products of individuals’ decisions to buy and sell, cast a ballot, or express anger. The classic example of this approach, which is known as methodological individualism, is provided by Adam Smith’s conception of markets as the simple sum of individuals’ willingness to supply or demand a good.

Another classic method used to understand collective human behavior dispenses with individuals and focuses exclusively on groups delineated by, say, class or race, each with collective identities that cause people in these groups to act in concert. Some scholars in this tradition, such as Karl Marx, believe that groups have their own “consciousness,” imbuing them with an indivisible personality that cannot be deduced or understood from the actions of its members. Others have focused on the primacy of group culture. For example, sociologist Émile Durkheim argued that the relatively constant rates of suicide among members of different religious groups across time could not be explained by the actions of any individuals since the groups had an enduring reality that long outlasted the lives of their members. How was it, he wondered, that people came and went, but the suicide rate in French Protestants stayed the same? Known as methodological holism, this approach sees social phenomena as having a totality that is distinct from individuals and that cannot be understood by merely studying individuals.

Individualism and holism shed light on the human condition, but they miss something essential. In contrast to these two traditions, the science of social networks offers an entirely new way of understanding human society because it is about individuals and groups and, indeed, about how the former become the latter. Interconnections between people give rise to phenomena that are not present in individuals or reducible to their solitary desires and actions. Indeed, culture itself is one such phenomenon. When we lose our connections, we lose everything.

The study of social networks is, in fact, part of a much broader assembly project in modern science. For the past four centuries, swept up by a reductionistic fervor and by considerable success, scientists have been purposefully examining ever-smaller bits of nature in order to understand the whole. We have disassembled life into organs, then cells, then molecules, then genes. We have disassembled matter into atoms, then nuclei, then subatomic particles. We have invented everything from microscopes to supercolliders. But across many disciplines, scientists are now trying to put the parts back together—whether macromolecules into cells, neurons into brains, species into ecosystems, nutrients into foods, or people into networks. Scientists are also increasingly seeing events like earthquakes, forest fires, species extinctions, climate change, heartbeats, revolutions, and market crashes as bursts of activity in a larger system, intelligible only when studied in the context of many examples of the same phenomenon. They are turning their attention to how and why the parts fit together and to the rules that govern interconnection and coherence. Understanding the structure and function of social networks and understanding the phenomenon of emergence (that is, the origin of collective properties of the whole not found in the parts) are thus elements of this larger scientific movement.

Better understanding of social networks is essential for facing new threats in our world. Turmoil in financial markets reminds us that economic activity is becoming increasingly globalized and increasingly interconnected. Emerging public health problems like drug-resistant pathogens and epidemics of risky behaviors are exacerbated by person-to-person spread. Political campaigns are taking greater advantage of new networking technologies, and more and more of our political life is taking place in a hyperconnected world; but these same technologies are used by a few extremists who would like to undo the very world that allows us to connect so well.

All of these challenges require us to recognize that although human beings are individually powerful, we must act together to achieve what we could not accomplish on our own. We have done it before—taming huge rivers, building great cities, creating libraries of knowledge, and sending ourselves into space. We have done it without even knowing all the other people we worked with to make it happen. The miracle of social networks in the modern world is that they unite us with other human beings and give us the capacity to cooperate on a scale so much larger than the one experienced in our ancient past.

But on a more human level, social networks affect every aspect of our lives. Events occurring in distant others can determine the shape of our lives, what we think, what we desire, whether we fall ill or die. In a social chain reaction, we respond to faraway events, often without being consciously aware of it.

Embedded in social networks and influenced by others to whom we are tied, we necessarily lose some of our individuality. Focusing on network connections lessens the importance of individuals in understanding the behaviors of groups. In addition, networks influence many behaviors and outcomes that have moral overtones. If showing kindness and using drugs are contagious, does this mean that we should reshape our own social networks in favor of the benevolent and the abstemious? If we unconsciously copy the good deeds of others to whom we are connected, do we deserve credit for those deeds? And if we adopt the bad habits or evil thoughts of others to whom we are closely or even loosely tied, do we deserve blame? Do they? If social networks place constraints on the information and opinions we have, how free are we to make choices?

Recognition of this loss of self-direction can be shocking. But the surprising power of social networks is not just the effect others have on us. It is also the effect we have on others. You do not have to be a superstar to have this power. All you need to do is connect. The ubiquity of human connection means that each of us has a much bigger impact on others than we can see. When we take better care of ourselves, so do many other people. When we practice random acts of kindness, they can spread to dozens or even hundreds of other people. And with each good deed, we help to sustain the very network that sustains us.

The great project of the twenty-first century—understanding how the whole of humanity comes to be greater than the sum of its parts—is just beginning. Like an awakening child, the human superorganism is becoming self-aware, and this will surely help us to achieve our goals. But the greatest gift of this awareness will be the sheer joy of self-discovery and the realization that to truly know ourselves, we must first understand how and why we are all connected.