I hope you enjoyed your trip.

Digital photo colorization is a modern incarnation of a very old craft. The first hand-tinted photographs were created through the careful application of colored powder, fixed in place by heat. Today, we use Adobe Photoshop.

Broadly speaking, the process I employed for each of the photographs in History as They Saw It followed the same set pathway. Stage one was to carry out a thorough appraisal of the level of damage that the photograph had sustained across time. This damage could be anything from a cracked glass plate, as was the case with the photograph of the hanging of the Lincoln conspirators (p. 178), to extensive destruction by mold, as seen on the photograph of daredevil Jammie Reynolds (p. 88).

Stage two was to implement an intensive digital clean and restoration, in order to ensure that the foundational black-and-white information underneath the later color could be as close to its original state as possible.

Following this, stage three was to block-in the color – a process that is simultaneously meditative and overwhelming in its detail. Blocking-in color requires one to digitally ‘paint’ layers of color onto the original photograph. How many layers? In some instances, thousands. I could expect a single face typically to have around fourteen or fifteen separate layers of color, simply in order to reflect the complex tones of skin. You can imagine how quickly the number of layers grows exponentially.

Alongside the color-blocking, my team and I carried out research. We catalogued all possible color references, asking ourselves oblique questions about the photographs and eliminating guesswork as much as possible. We contacted all manner of experts in everything from obscure 1930s soda manufacturers to Napoleonic uniform livery. The results were dozens upon dozens of color illustrations and pages upon pages of hyper-specific descriptions.

When that research had been collated and prepared, stage four was to use it all to transform, incrementally, the garishly colored, blocked-in color layers. Each layer of many thousands was adjusted to mirror the color and lighting references – hundreds of decisions based on my working knowledge of lighting, perspective, atmosphere and particular photographic processes.

For me, this was the magical part of the work – witnessing the way color seemed to emerge from the original photograph almost organically. It was at this point that details I had somehow completely overlooked before would suddenly leap out from the screen – like the chicken scratching about in front of the Gordonton country store (p. 18).

The goal of a colorizer should be to create work that is so authentic that the color itself becomes unremarkable. For me, the images in this book are inherently extremely powerful, with or without color, and this I attribute to the singular curatorial talents of Wolfgang Wild. Wolfgang also uses a rigorous yet unseen process, but, to the rest of us, he appears to be able to glance momentarily at a near-infinite stream of photographs and immediately pull out something unbelievable.

This is the process I went through on each of the photographs in History as They Saw It. As I worked, my hope was that when I had finished you might feel, if only just for a moment, as though you were standing next to the photographer when the shutter clicked.

Jordan J. Lloyd

North State Street, Chicago, USA (Stanley Kubrick / Look Magazine / Library of Congress) pp. 4–5

This scene is flooded with color and light, from the neon sign to the left of the theater, to the huge number of bulbs on the underside of the theater’s portico – all reflected in the rain covering the street surface. The Chicago Theatre still retains its spectacular marquee of lights, although it had been replaced in the year this picture was taken. The left-hand car is a 1948 Pontiac Silver Streak Coupe, and the car under the ‘Chicago’ sign is a Chevy Fleetline 2-door Aero Sedan.

Hawthorne, California, USA (Unknown / Underwood Archive / Getty) pp. 8–9

The market for model aircraft is huge and several modelling projects of the XB-35 exist. I cross-referenced these kits with a number of original color photographs of the bomber. I then used contemporaneous examples of clothing and tractors for the surrounding details.

Times Square, New York City, USA (William Gottlieb / Library of Congress) pp. 6–7

We used around two dozen reference images for Times Square itself, as well as individual signage. The only internationally recognizable elements of this image that still exist today are the statue of Father Duffy and Pepsi-Cola. The whiskey brand Kinsey went out of business in the mid-1980s, although Four Roses bourbon is still in operation, produced by Japanese beverage giant Kirin. Ruppert beer disappeared from the market at the end of 1965. The Warner Bros Strand Theatre was knocked down in 1987 and is now the site of the Morgan Stanley building.

Exeter Airfield, Devon, UK (US National Archives) pp. 10–11

In creating this image, I was able to draw on the expertise of the huge community of Second World War enthusiasts and re-enactors who collect original or replica uniform and detailing, such as the M7 carrier for the M5 gas mask. In the background is a Douglas C-47 Skytrain.

Pacific Theatre of War (Library of Congress) pp. 12–13

The livery on the bomber is rendered in the Pacific variant rather than the Atlantic one, and, as with many things concerning the military, it was well documented. An aircraft-carrier’s deck would exhibit signs of sea water, paint, fuel, oil, fire and rubber, so I incorporated this into the details.

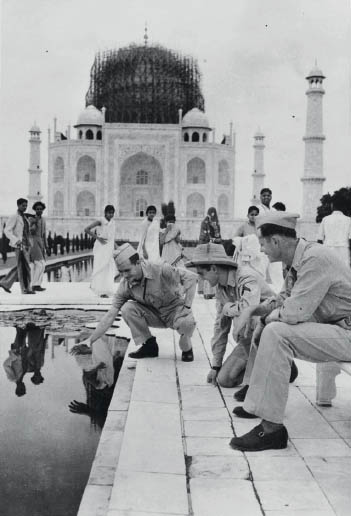

Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India (Uknown / Library of Congress) pp. 14–15

When this picture was taken, only the dome was covered. Later, the entire structure would sit within a bamboo framework. Uniforms and clothing were sourced from contemporaneous examples.

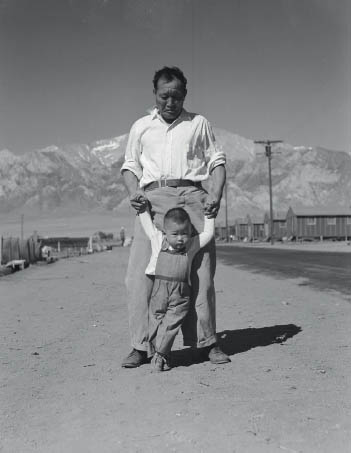

Manzanar, California, USA (Dorothea Lange / Library of Congress) pp. 16–17

The barracks, some of which still stand today, are located within the Owens Valley. I believe the shot is taken looking east towards the mountains of Mount Keith and Mount Bradley in the Sierra crest, which indicates this shot was taken around late morning.

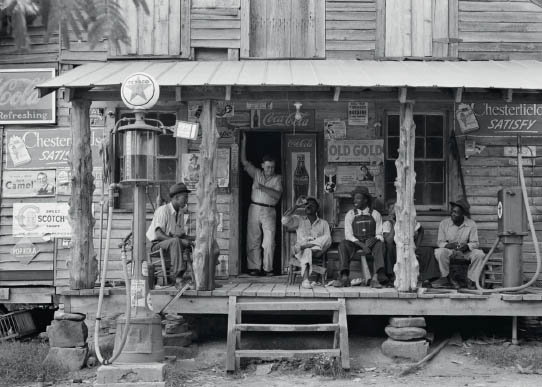

Gordonton, North Carolina, USA (Dorothea Lange / Library of Congress) pp. 18–19

We hunted down visual references to each original sign in the bewildering array on display here, using auction sites, collectibles and, in one case, a specialist soda pop retailer. We had to make sure we were referring to the right geographical source, as some signs even had regional variations. We also had access to a set of photographs that show the now-derelict building – though I needed to adjust the information to show that the building was around eighty years younger in Lange’s photograph.

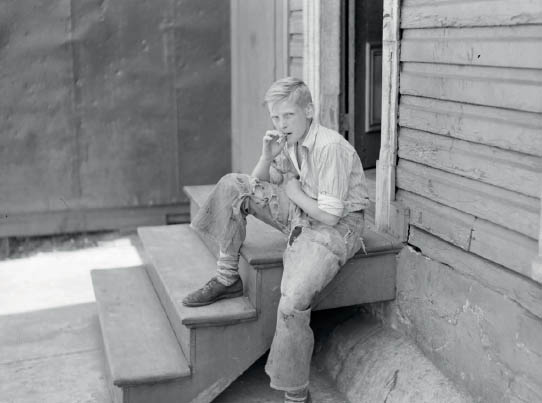

Baltimore, Maryland, USA (John Vachon / Library of Congress) pp. 20–21

This is a picture with a very narrow range of color, and a very wide range of texture, from the pitted metal at the left, to the rough hewn pine boards on the right. I was able to look at a range of examples of utility and work-wear for reference, and also examples of painted timber in the background. Today, the boy´s jeans would be worth an absolute fortune.

Leningrad, Soviet Union (Viktor Bulla / Getty) pp. 22–23

The blue of a Young Pioneer uniform varied from navy to mid-blue, while the scarf was a standard tomato red. The truck is a Zis5. The forests outside St. Petersburg (the former Leningrad) are largely birch and pine – the pine needles have a particular yellow tonality.

Watsonville, California, USA (Dorothea Lange / Library of Congress) pp. 24–25

Examples of working-class clothing of the period provided much of the references for our work on this image. While not remotely taking away from Lange’s extraordinary original, the addition of color seems to emphasise the sheer desperation and anguish of Mrs. Thompson’s situation.

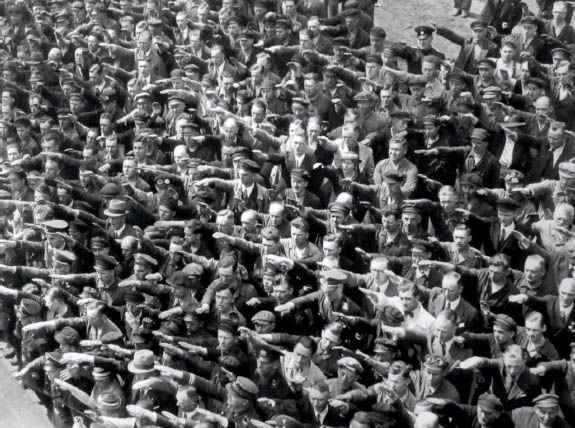

Hamburg, Germany (Hulton Archive / Getty) pp. 26–27

Crowd scenes such as this one may appear to be highly complex to carry out but can, in fact, be relatively straightforward in practice – if inordinately time-consuming. That was the case with this image. The crowd is composed of a mixture of both civilians and uniformed figures. We looked at similar crowd scenes in Nazi Germany, many of which do exist in color. There is a very wide range of Nazi uniforms in this picture, all extensively documented today, in addition to the examples of 1930s civilian dress.

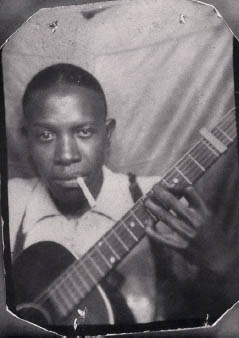

USA (Unknown) pp. 28–29

Needless to say, I listened to Robert Johnson’s seminal recordings on loop while working on this rare photograph. It was essential to ascertain the precise model of guitar that Johnson is holding, though there is little of it showing. Despite this, we believe it to be a 1936 Gibson L-00 featuring a black ebony-finished sunburst mahogany body and a rosewood fingerboard.

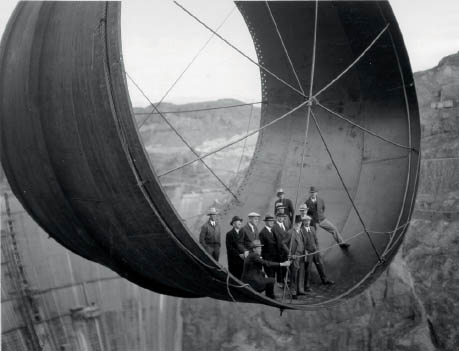

Hoover Dam, Arizona, USA (Unknown / Bureau of Reclamation) pp. 30–31

Much of Hoover Dam looks exactly the same today as it did back in 1935, so we were able to color reference the surrounding geology using satellite and contemporary color photographs.

San Francisco, California, USA (Chas Hiller / Library of Congress) pp. 32–33

International Orange is a very precise shade. The CMYK colors are: C = Cyan: 0%, M = Magenta: 69%, Y = Yellow: 100%, K = Black: 6%. On the bridge, the International Orange primer is continually repainted, completed every twenty years. The original paint was lead-based but from 1965 has been replaced by a zinc-based primer and acrylic topcoat. Although it is now illegal for pedestrians to venture under the bridge, historically original rivets have been found in the water, complete with their International Orange paint. We used aerial and satellite photography as reference points for the surrounding geology, and were fortunate to draw on a range of near and far side Kodachrome images taken across the next twenty years, including one from the family collection of History as They Saw It researcher Deborah Humphries. Taken together, these gave us a good range of variations for water and sky color.

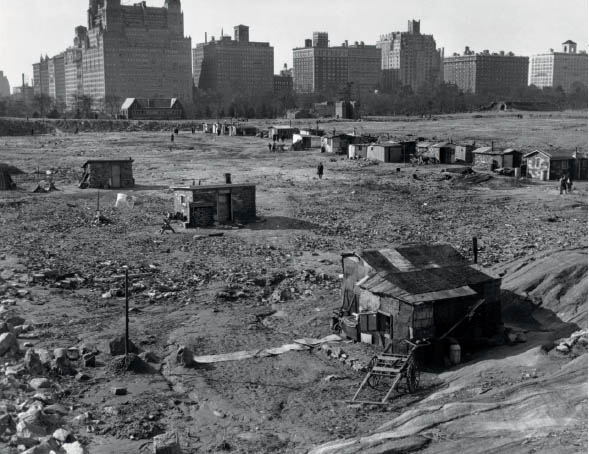

Central Park, New York City, USA (Unknown / Bettman / Getty) pp. 34–35

This site is now part of the Great Lawn at Central Park. We could draw on modern pictures of several elements of the scene, including the distinctive gray stone, Manhattan schist rock. The large building to the left is The Beresford apartment block, built in 1929 and still in place today. It has a limestone base, brick-clad upper floors and terracotta detailing. Indeed, the entire skyline to the right of The Beresford is essentially identical today.

Weston-super-Mare, Somerset, UK (Fox Photos / Getty) pp. 36–37

I found an article in the May 1932 issue of Popular Science on the Dynasphere ‘unicycle’. The article locates this image specifically on Brean Sands, near Weston-super-Mare, from which I was able to generate modern-day color references.

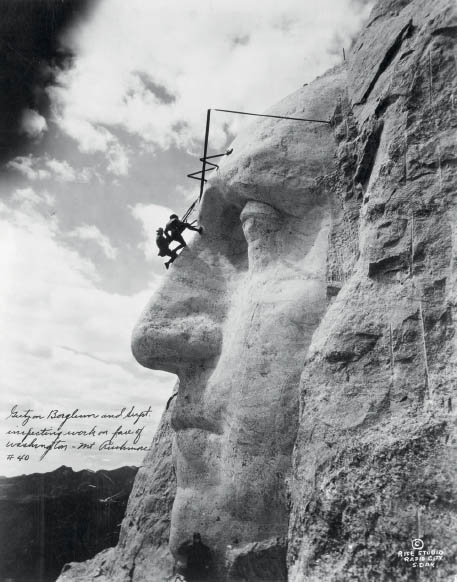

Mount Rushmore, South Dakota, USA (Unknown / Library of Congress) pp. 38–39

This is another very well-documented monument, so sourcing good quality color references was fairly straightforward. My favorite detail in the image is the smudge on the top left, which I believe to be the finger of the photographer creeping into the shot.

Garment District, New York City, USA (Margaret Bourke-White / Time & Life Pictures / Getty) pp. 40–41

There are some interesting details in this picture: a barber pole, a Coca-Cola sign, litter in the gutter and, on the far right, a news stand with periodicals. There are over 600 people in this photograph, and no shortcuts were taken filling in the color from dozens of examples of clothing at the time. The two cars shown are (left) a 1930 Ford Model A 4-Door Sedan and (right) a Ford Model A Sports Coupe. Examples of the cars were also found after we managed to identify them.

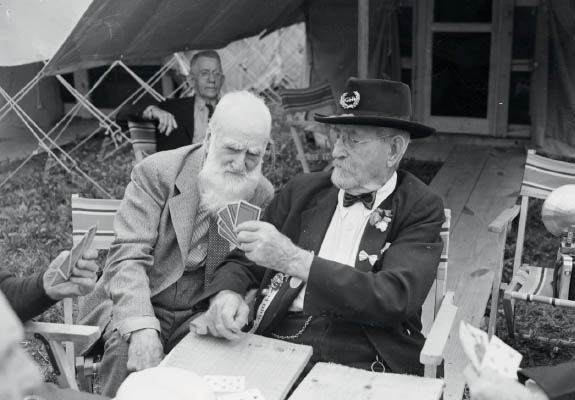

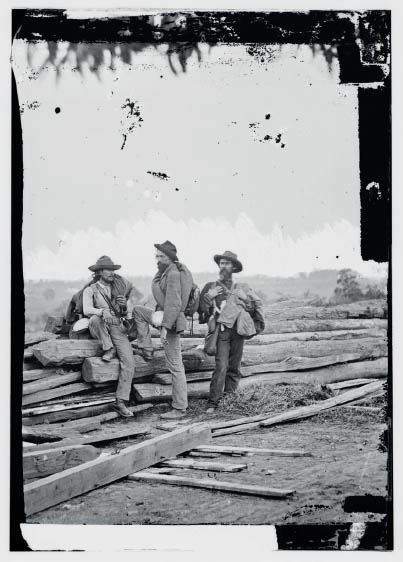

Gettysburg Battlefield, Pennsylvania, USA (Bettmann / Getty) pp. 42–43

The man on the right wears a Union ‘GAR’ (Grand Army of the Republic) hat pin on his Slouch hat. He also wears a Gettysburg 50th Reunion medal, dating from 1913. The long ribbon below his left hand appears to be a Florida State ribbon. Florida was a Confederate State – perhaps this man had moved to Florida after the war.

Somewhere above the earth (A. R. Coster / Getty) pp. 44–45

The lighting of this photograph is extraordinary and this remains one of my favorite photographs. My absolute favorite detail, as I pointed out to Wolfgang when he asked, are the doodles on the dust on one of the glass panes.

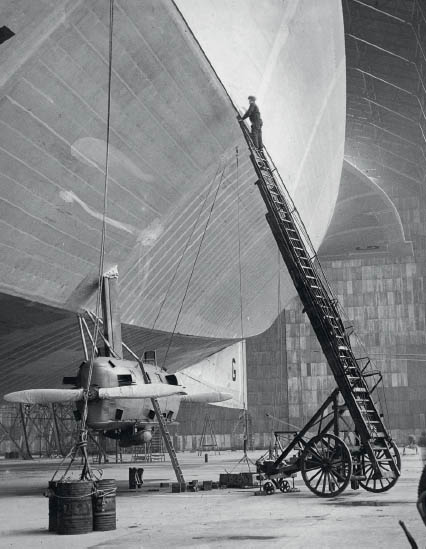

Howden, Yorkshire, UK (Fox Photos / Hulton Archive) pp. 46–47

The rear walls of the No. 2 Double Rigid Shed are rusting corrugated iron sheets – the shed was known to have a leaky roof.

Piccadilly, London, England (Topical Press / Getty) pp. 48–49

Eagle-eyed readers will note the damage in the top left-hand corner of the black-and-white photograph, which in the end I had to reconstruct digitally from a photograph I myself took at the exact angle and location. The livery of the London Midland and Scottish Railway is quite distinctive.

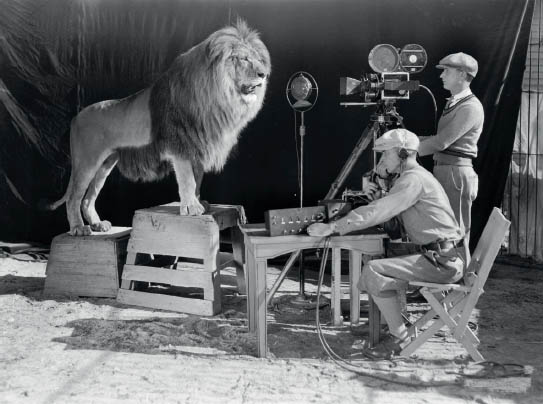

Hollywood, California, USA (John Kobal Foundation / Getty) pp. 50–51

The camera is a Bell & Howell 2709 and is now very rare, with only around ten surviving examples. In 1928, the 2709 was the pinnacle of camera technology and the highest-priced device on the market. With a brass frame on its side, the body was machined from cast aluminium. The camera has wooden legs, with a steel-geared head.

Kingsway, London, UK (Unknown / Fox Photos / Getty) pp. 52–53

The London plane trees in this photograph, in their infancy during the 1920s, have now fully matured. Many of the stone-fronted neo-classical and neo-baroque buildings have been completely replaced. London County Council Tramways produced a poster during the 1920s, which included the Kingsway Tramway sign, providing me with the dark red tone. The car immediately behind the flock is a Renault.

East Potomac Park, Washington DC, USA (Library of Congress) pp. 54–55

Working from a photomechanical color postcard and cross-referencing satellite imagery, we could establish that this picture was taken on the morning of Saturday, March 28, 1925. I can only use hand-colored or tinted images as general guidelines, as often the companies that created the postcards were not necessarily the people who took the image. In this case, much of the location remains the same, so I could use contemporary photographs as well as examples of children’s kimonos of the period.

Glacier National Park, Montana (Bain News Service / Library of Congress) pp. 56–57

Helen’s feathers are likely to be from a turkey, and her ring may well be silver with turquoise. Being of the Blackfoot Nation, examples of the blanket’s distinctive blue, red and ochre striping were sourced from numerous examples and paintings.

Hollywood, California, USA (Underwood Archives / Getty) pp. 58–59

The Hollywoodland sign itself was built from sheet metal and wooden telephone poles. The traction engine is part of the Western Construction Company. Kanst’s Art Gallery, with its red tile roof, was brand new in 1924 – it opened on April Fool’s Day. The car is likely to be a Studebaker Special Six.

Washington DC, USA (Library of Congress) pp. 60–61

It´s hard to be absolutely certain without visiting but the details suggest this is the Capitol Building, and so I took my references from there.

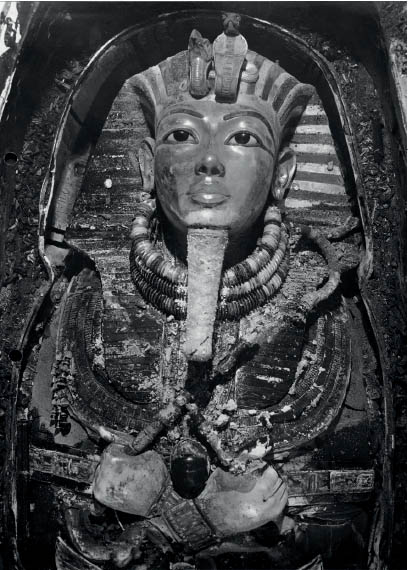

East Valley of the Kings, Luxor, Egypt (Harry Burton / The Griffith Institute) pp. 62–63

Archaeologist and Egyptologist Howard Carter kept meticulous handwritten notes on flashcards describing in great detail the array of artifacts that were placed in the tomb. We cross-referenced all the elements in the photograph to the original notes with the restored artifact in the Museum of Egypt, and then dulled down the result to reflect over 3,000 years of dust and ageing.

Atlantic City, New Jersey, USA (Bettmann / Corbis / Getty) pp. 64–65

Miss America wore a sea-foam green and sequin dress on this occasion, in keeping with the overall maritime theme. After her time as Miss America, Margaret kept the dress, storing it in in the back of her cupboard. I didn´t have access to Margaret´s cupboard, so I used modern examples of a green chiffon dress instead.

Bolling Field Air Force Base, Washington DC, USA (Unknown / Getty) pp. 66–67

Although there are no contemporary images taken of the location as it stands today, much of the fauna in the foreground and background is sourced from the surrounding area. The distinctive red brick and dressed stone of the Beaux Arts style National War College by McKim, Mead and White is still in use today by the National Defense University.

Near Amesbury, Wiltshire, UK (English Heritage / Hulton Archive) pp. 68–69

Stonehenge is one of the world’s most documented sites, so there were plenty of reference photographs of the trilithons for me to choose from, though determining the location from which the photograph was taken proved to be a more substantial challenge. In the end, satellite imagery in addition to inspecting a 3D model of the site allowed us to find a possible angle.

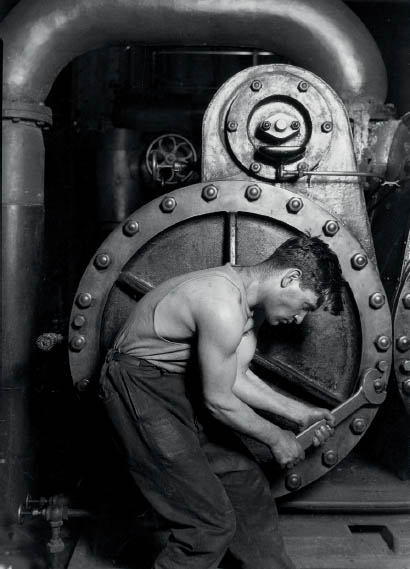

Unknown location, USA (Lewis Hine / US National Archives) pp. 70–71

The machinery in this picture would not have been painted, because paint would not have survived the range of temperatures and conditions to which it was exposed.

Unknown location (US National Archives) pp. 72–73

You might be able to notice that the soldiers are all wearing the Croix de Guerre (1914–18), a French medal recognizing courage or gallantry to a member of the French military or allied force. It is testament to the unit that by the end of the war, 171 members of the 369th were awarded either the Croix de Guerre or the Légion d'Honneur.

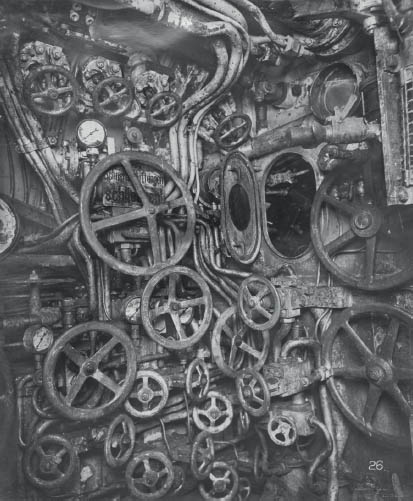

Wallsend, Tyne and Wear, UK (Tyne and Wear Museums & Archives) pp. 74–75

Given that the 110 U-boat had only been sunk for between three to four months, there is no real rust or other water damage to be seen in this shot. The black coloration is the result of the accumulation of grease, oil and soot, prior to the craft being rammed and depth-charged. The background wall color is, in fact, ivory. As you can imagine, color coding was vital to the operation of such a complex array of controls. Wheels and levers to be opened on ‘rig for dive’ conditions are red; wheels and levers to be closed on ‘rig for dive’ are green. Many controls, gauges and dials also used luminous paint.

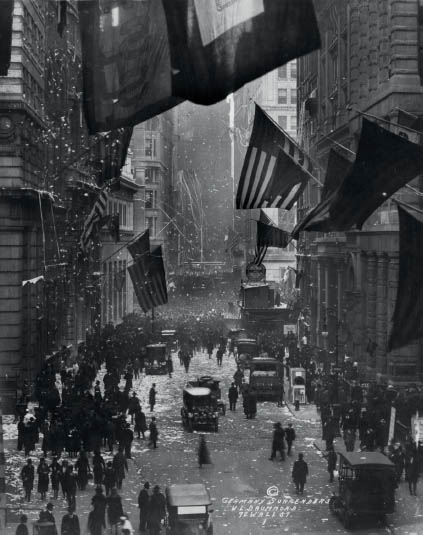

Wall Street, New York City, USA (W. L. Drummond / Library of Congress) pp. 76–77

The street and sidewalks are littered with ticker tape: paper tape created by the machines used in stock brokerages to give up-to-date stock prices. Ticker is derived from the printing noise made by the machine. During the war, clothing became more and more subdued in color, as more and more people were affected – often directly – by the deaths of people for whom they cared. Famously, a poster issued by the British National Savings Committee in 1916 stated, ‘To Dress Extravagantly in War Time is Worse Than Bad Form; It is Unpatriotic.’

Amiens, France (Unknown) pp. 78–79

Thankfully, the anticipated destruction of the cathedral did not come to pass and therefore most of the detail could be sourced from contemporary color photography. The carpets and ornaments in the foreground were sourced from other examples.

Rosyth, UK (Topical Press / Getty) pp. 80–81

The distinctive black-and-blue striping of the HMS Argus was actually referenced from a scale model of the ship at the Fleet Air Arm Museum in Somerset, UK – it was the most accurate color reference I could find. Numerous other scale models and schematics exist, although, sadly, no color photographs.

Kelly Field, San Antonio, USA (Paul Aldin Smith Kelly Field Album / San Diego Air & Space Museum) pp. 82–83

There are two choices for the identity of this plane: it is either a Curtiss JN-4 Jenny biplane or De Havilland DH-4. Some of the De Havillands were painted in a khaki color, others in yellow, while all Jennys were yellow. So that’s two against one in favor of yellow.

Fort Sill, Oklahoma, USA (Library of Congress) pp. 84–85

I honestly have no idea how the photographer captured the exact moment of the explosion, but the addition of color does add a real sense of urgency to the servicemen scrambling around trying to get away from immediate danger.

Union Square, New York City, USA (Bain News Service / Library of Congress) pp. 86–87

We know exactly where the USS Recruit was built and situated and many of the buildings in Union Square remain the same today, so it was fairly straightforward to obtain contemporary color references.

Washington DC, USA (Unknown / Library of Congress) pp. 88–89

As you can see, the glass plate negative shows extensive damage to the original coating, and the initial restoration work here took me several days. Often with restoration, my aim is to fix the blemish while retaining the overall shape and texture of the undamaged surroundings. We took color references from modern images of buildings that have survived, and from hand-colored postcards of the time. Based on maps and the angle of various landmarks, I could also figure out the exact location and angle of the photograph – and just in case you were wondering how high that drop is, it's a good six or seven stories off the ground, as shown by another photographer’s image of Reynolds, taken from the ground.

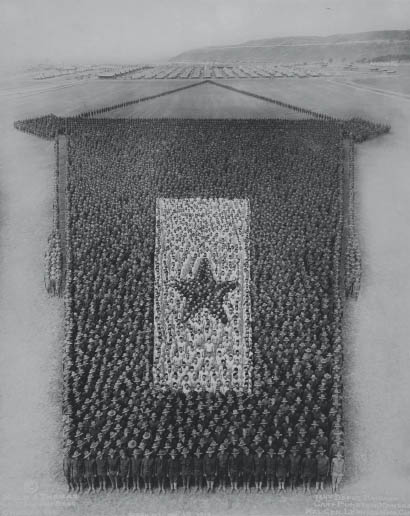

Fort Riley, Kansas, USA (Arthur Mole / Libray of Congress) pp. 90–91

Arthur Mole would dress soldiers in a range of uniforms to enable him to show dark and light details in his photographs. He also had some figures hatted and others he left bare-headed, and he would also leave spaces between lines to create further shadows. For this colorization, we looked at the summer and winter uniforms of the 164th. An actual service banner has a red border, a white interior, and a dark blue star.

Beaumont-Hamel, Somme, France (Lt. Ernest Brooks / IWM / Getty) pp. 92–93

The 1916 Mark I model helmet of 1916 had a matte khaki paint finish. Cork, sand or sawdust was then used to further reduce shine. Surprisingly, Brodie’s original suggested color scheme was a camouflage of light green, blue and orange.

Buckingham Palace, London, UK (Topical Press / Getty) pp. 94–95

Contemporaneous examples of civilian and police clothing were sourced for this photograph, though the sun coming in from behind adds an extra technical challenge. Often, the color hues slightly change from a known sample to match the overall environment.

Brixton, London, UK (Unknown / Hulton Archive / Getty) pp. 96–97

The buses advertise brands that still survive today, such as Colman’s Mustard and Heinz soup. Gossages Soap as seen on the LCC tram is no longer sold. The building in the background next to the buses is a Woolworths branch, the sixth Woolworths store to open in Britain at the time. The railway bridge is still in place today. The ‘Quin and Axtens’ sign, an advert for Quin and Axtens’s Brixton drapery department store, is likely to be constructed from wood, rather than painted. Note that the letters cast a shadow. The ‘mill . . .’ is the beginning of the word ‘milliner’s’, or hat-maker’s.

Boulevard de Strasbourg, Paris, France (Eugène Atget / George Eastman House) pp. 98–99

These French Mannequins are likely to be wax and are similar to those created by Pierre Imans – examples of which are, in real life, quite eerie. From a technical perspective, this was an extremely challenging image due to the sheer amount of reflective material present in the photograph, from the display mirrors to the reflection of the street.

USA (Schenectady Museum; Hall of Electrical History Foundation / Getty) pp. 100–101

The young woman is standing next to a hand-cranked battery charger for a Columbia Mark 68 (LXVIII) Victoria automobile by the Pope Manufacturing Company of Hartford, Connecticut.

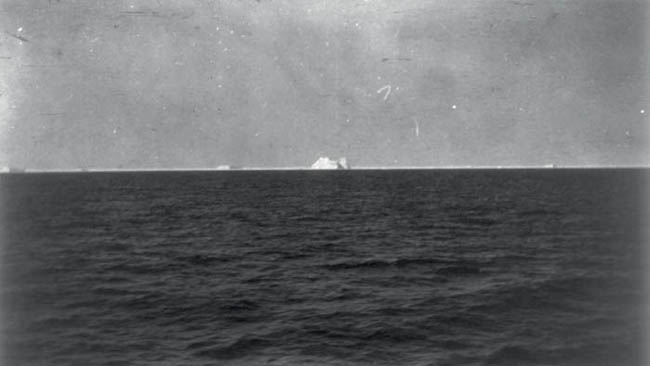

North Atlantic (Universal Images Group / Getty) pp. 102–103

Another truly astonishing photograph, I remember my mouth dropping open when I saw it for the first time – it had never even occurred to me that someone might have taken a picture of the iceberg shortly after the Titanic sank.

Antarctica (Herbert G. Ponting / Getty) pp. 104–105

What strikes me about photography of the Antarctic region is the color saturation, in a location where one might expect to find none. As such, many examples from magazines such as National Geographic provided excellent references: in this case, at least a dozen. What the reaction was to the original photograph at the time of publication is hard to say. Anything other than astonishment would be surprising – for me, the natural reaction to this bleak, alien landscape.

Sentinel Island, Alaska, USA (William Howard Case / Frank G. Carpenter / Library of Congress) pp. 106–107

Another extremely difficult image to work on, partly due to the sunlight coming in on the left of the photograph, as well as the overall quality of the image. Contemporary photographs of the area provided references for the water and rocks, and hand-tinted color postcards for the ship.

Unknown (Unknown / Simple Insomnia) pp. 108–109

There is a curious social phenomenon surrounding the expressions of subjects in early photographs – they are mainly serious. One reason might be that, in the very earliest days, the long exposure times meant that subjects couldn’t move to prevent blurring, and it´s difficult to smile for a long period of time. However, this particular reason became less of an issue as new camera technologies became available. A more likely cause was that having one’s photograph taken was an expensive affair for ordinary people, and they typically wanted to give it the gravitas such an occasion deserved as they emulated old portraits of the wealthy rendered in paint, resulting in relatively few jovial and candid expressions.

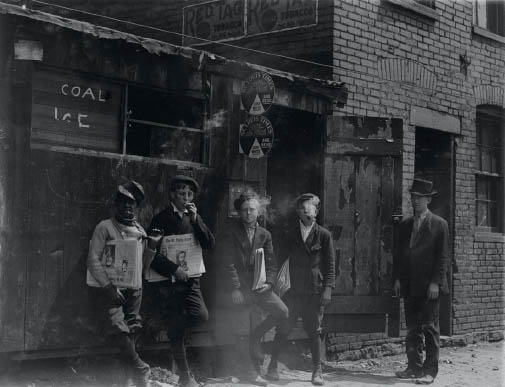

St. Louis, Missouri, USA (Lewis Hine / Library of Congress) pp. 110–111

Examples of older buildings in St. Louis provided clues as to the shade of brick, and the signs were pieced together from auction sites or brand colors. One of my favorite details is the newsprint pasted onto the inside of the door.

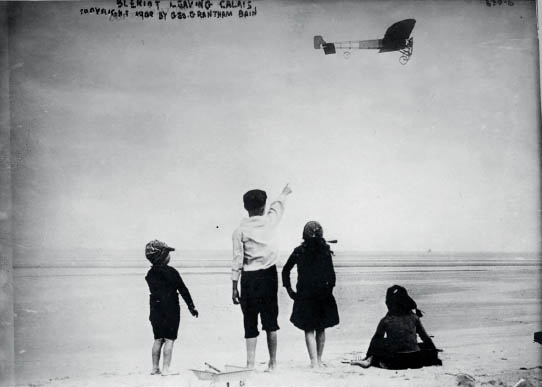

Calais, France (Library of Congress) pp. 112–113

We used contemporary images of the same stretch of coastline, in addition to sampling colors directly from the original Blériot XI plane.

Turkey Knob Mine, MacDonald, West Virginia, USA (Lewis Hine / Library of Congress) Gatefold – p. 114

Breaking the darkness, the brief explosion of color seen in the camera flash is sourced from contemporary examples of other mines within the region.

San Francisco, California, USA (George R. Lawrence / Library of Congress) Gatefold

The research carried out for this image was, to say the least, extensive. We began by establishing, as far as possible, the exact location and angle of the camera. We also identified the names and locations of as many extant buildings as possible. Five actual color photographs, taken of the scene in 1906, still exist. In addition to this set, we compiled around 120 other reference photographs, postcards, paintings and drawings. We also drew on insurance maps showing the damage, and in particular, the burn areas. As for shipping, documents tell us that craft present at this time included the USS Boston, the USS Princeton, the USS Independence, the US Training Ship Pensacol, the cutter Golden Gate, and the steam schooner Chetco.

Syracuse, New York, USA (Detroit Publishing Company / Library of Congress) Gatefold – p. 115

We drew together modern color photographs and hand-tinted postcards to source colors of the now demolished Yates Hotel in the foreground left of the photograph. The buildings in the background on E. Genesee Street are also intact. The engine number is 3837, originally built as 2897 and then renumbered in the mid-1920s.

Skagit County, Washington, USA (Darius Kinsey / Getty) pp. 116–117

Painting and repainting engines in liveries was very much a nonessential expense for logging companies. Their locomotives were workhorses and dirty. Around 100 Shay engines survive today – this one was scrapped, so far as we can tell, in 1952. The men are in denim workwear.

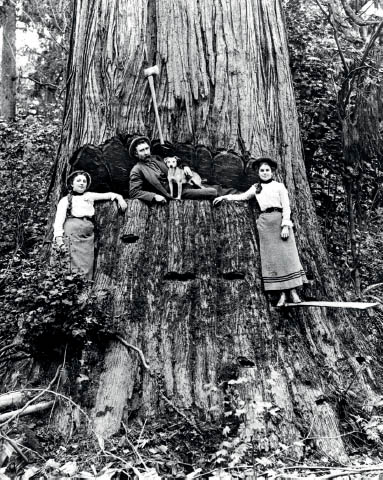

Seattle, Washington, USA (Darius Kinsey / Library of Congress) pp. 118–119

Contemporary images of the region were used for color reference. When it comes to people, a trick I use often is to find a color photograph of someone who looks very similar to the subject, perhaps someone I know, or a famous actor. In this case, the woman on the right looks quite similar to a friend of mine.

Coney Island, New York City, USA (Geo. P. Hall & Son / New York Historical Society / Getty) pp. 120–121

I drew on half a dozen hand-tinted color postcards for this image – although the colors displayed varied from one postcard to another, which illustrates the point that much of early color was not about accuracy, but commercially driven vibrancy. In the end, I achieved a visual consensus by finding matching colors across several postcards and cross-referencing these results with the colors suggested by the black-and-white information on the original monochrome.

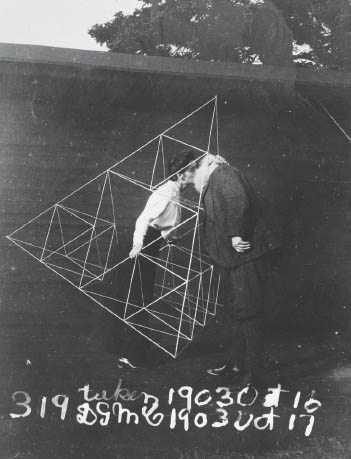

Baddeck, Nova Scotia, Canada (Library of Congress) pp. 122–123

Looking at maps and satellite imagery, I believe this photograph was taken outside one of Bell’s laboratories on his private estate of Beinn Bhreagh in Nova Scotia. Contemporary photographs gave an indication of the background tree and wood of the cabin.

Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, USA (Wright Brothers / Library of Congress) pp. 124–125

Despite its seemingly simple composition, this image was in fact one of the hardest images to work on in the entire book. This is because much of the texture on the original plate is not, as it appears, detail of the sand dune, but rather damage to the substrate of the plate. Thankfully, the test runs at Kitty Hawk are well documented and I was able to digitally reconstruct the most heavily damaged parts of the photograph with other photographs of the same location on a different day, or at a slightly different angle on the same day. Numerous contemporary examples of models and color images exist, though notably a full-size model of the flyer itself exists at the Wright Brothers National Memorial visitor center in North Carolina.

San Francisco, California, USA (Unknown / Library of Congress) pp. 126–127

There are some really great contemporary photographs of this exact location, which provided a solid foundation for getting an accurate overall atmosphere. As the original photograph is sensitive to blue light, the sky you see in the photograph is actually composited in and blended with photographs. Making sure the sky haze blends in with the detail is a very challenging part of the process. Other references, such as the house, are sourced from hand-tinted postcards, which surprisingly were all consistent in their renditions. The clothing of the hundreds of people on the beach were all sourced from real examples of the period.

Broadway, New York City, USA (Detroit Publishing Company / Getty) pp. 128–129

New York Public Library holds a set of colored-pencil elevations of the blocks on Broadway. The set was issued in 1899 so they provided an excellent color reference, short of actual photographs. Fortunately for me, the elevations on 5th Avenue (to the right) haven’t changed a great deal since this photograph was taken and – to my astonishment – some of the businesses are still located in the same address, such as the Brooks Brothers store on 670 Broadway, the red brick building seen to the left of the Flatiron.

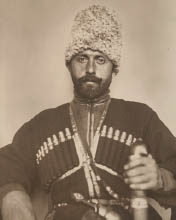

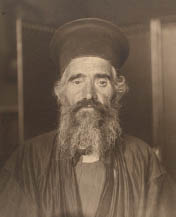

Ellis Island, New York City, USA (Augustus Francis Sherman / New York Public Library) pp. 130–135

The San Francisco panorama (gatefold) was the photograph that required the most detailed research. However, this set of images showing immigrants to Ellis Island, wearing their national dress, came a close second. Every single element, from thread to stitching to buttons, had a very specific and original color – or, rather, colors, as the costumes are highly regional. Sometimes, even with our best efforts, we found we couldn’t trace a particular material. I became paranoid about making an error and finding that I had inadvertently but understandably offended a large number of people. We released this set of images online around a year before the book was published, to generate publicity and support for the book’s crowdfunding campaign through Unbound. This proved helpful to our research, as a number of online commenters pointed out detailed corrections for the series. Fortuitously, we were then also contacted by Jan T. Letowski, specialist in European ethnographic dress and founder of the Museum of Ethnic Dress and Adornment, whose help was invaluable. Some elements in these pictures, such as the bunad on the Norwegian woman and the Bavarian man, match the museum examples Jan showed us almost exactly.

Gákti is the traditional costume of the Sámi people of the Arctic regions spanning from northern Norway to the Kola Peninsula in Russia. Traditionally made from reindeer leather and wool, velvet and silks are also used, with the (typically) blue pullover supplemented by contrasting colored banding of plaits, brooches and jewelry. The decorations are region-specific.

Hailing from the Germanic-speaking region of Alsace, now in modern-day France, the large bow in this regional dress is known as a schlupfkàpp and was worn by single women. The bows signified the bearer’s religion – Protestants generally wore black, while Catholics favored brightly colored bows.

While there are clues in her garments, the exact home village of this Ruthenian woman – as she was originally titled – is uncertain. Her costume is characteristic of the Bukovina region, which is today divided between Ukraine and Romania. The embroidered motifs on her linen blouse suggest that she is likely from the Ukrainian side, but useful details are concealed by the lack of color in the original image.

This man is wearing a traditional costume that enjoyed widespread popularity throughout the Caucasus, most notably among the population living in modern-day Georgia. The choka overcoat along with the traditional swords and daggers were seen both as elements of folk dress and military uniform. The rows of tubes across his chest are metal-capped wooden gunpowder containers.

Dominating the photograph is a traditional shepherd’s coat known as a sarica, made of three to four sheepskins sewn together. Depending on the region and style, a sarica could be worn either with the fleece facing inwards, as seen here, or outwards, resulting in an entirely different aesthetic. The size and softness of the garment also made it suitable for use as a pillow when sleeping outdoors.

Elements of this dress may have been homemade, though the kerchief and earrings would have had to have been purchased – a considerable expense for many peasants. The color and cut of garments were often region-specific, though manufactured elements such as shawls were a common feature throughout Italy. For special occasions, women often wore highly decorative aprons made of floral brocade.

The topi (cap) is worn all over the Indian subcontinent with many regional variations. It is especially common in Muslim communities where it is known as a taqiyah. Both the cotton khadi and the prayer shawl are likely to have been hand-spun on a charkha, and were used all year round.

The elaborate tartan headpiece, symbolizing marital status or mood, worn by Guadeloupean women can be traced back to the Middle Ages. First plain, then striped and in increasingly elaborate patterns, the Madras fabric exported from India and used as headwraps was eventually influenced by the Scottish in Colonial India, leading to a Madras-inspired tartan known as ‘Madrasi checks’.

Traditional dress in Bavaria is known as Trachten and there are many regional variations. In the Alpine region, leather breeches known as Lederhosen were worn by men and became part of the typical Bavarian style known as Miesbacher Tracht. This standardized form is now typically associated with the annual Oktoberfest. The grey jacket is made from fulled wool and decorated with horn buttons.

The truncated, brimless felt cap is known as a qeleshe. Its shape was largely determined by region and molded to one’s head. The vest, a jelek or xhamadan, was decorated with embroidered braids of silk or cotton. Color and decoration denoted the regional home of the wearer and their social rank. This man is likely to come from the northern regions of Albania.

The vestments of the Greek Orthodox church have remained largely unchanged. In this photograph, the priest wears an anteri, an ankle-length cassock (from the Turkish quzzak, from which the term ‘Cossack’ also derives) worn by all clergymen over which an amaniko, a type of cassock vest, is sometimes worn. The stiff cylindrical hat is called a kalimavkion and worn during services.

The Dutch bonnet was usually made of white cotton or lace. The shape of the headdress, in addition to the gold pins and square stikken, identifies where this woman is from (South Beveland), her religion (Protestant), and her marital status (married). Necklaces were often red coral, though black was common during mourning. Elements of the dress changed depending on the availability of fabrics.

Evolving since the 1750s, the Danish dress was simple with more decorated attire saved for special occasions. As with many nations before mass industrialization, much of the clothing was homespun. In contrast, this man is wearing items made of commercial cloth and a hat that suggests he is wearing a uniform rather than a strictly regional costume. His tailored jacket is decorated with metal buttons and a chain.

This man's sheepskin garments are noticeably plainer than the shepherd seen earlier, indicating his relative lack of wealth. He is likely a farm laborer, but the fact that he has posed with an instrument could suggest that his earnings were supplemented at least in part by playing music. The waistcoat, known as a pieptar, was worn by both men and women and came in a variety of shapes, sizes and ornamental styles.

The large turban-style headdress is made up of a large square of fabric folded and wrapped around a fez hat and secured using a special cord. Visible beneath the djellaba robe is a multi-colored, striped silk belt that was common throughout the Ottoman Empire. These belts had different regional names, for example, taraboulous, revealing the city where they were made: Tripoli (Tarabulus in Arabic).

Bunad is the the Norwegian term for regional clothing that developed through traditional folk costumes. In some regions the bunad is a direct continuation of the local peasant style, while in others it was reconstructed based on historical information and personal tastes. This woman is wearing a bunad from the Hardanger region, one of the most famous in all of Norway. The main elements are decorated with beadwork.

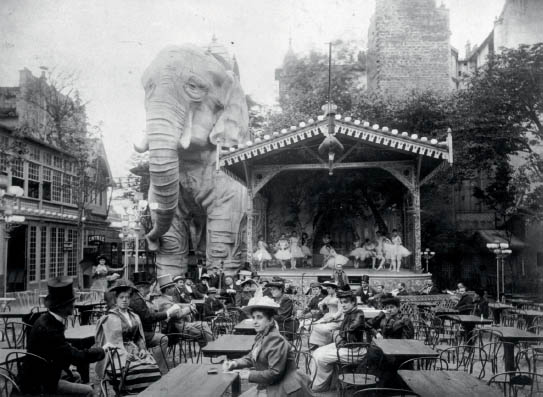

Boulevard de Clichy, Paris, France (Unknown / Hulton Archive / Getty) pp. 136–137

We drew on two rare 1920s Autochrome color photographs of the Moulin Rouge, as well as early photochrom postcards and paintings. Clothing colors were sourced from a range of museum collections.

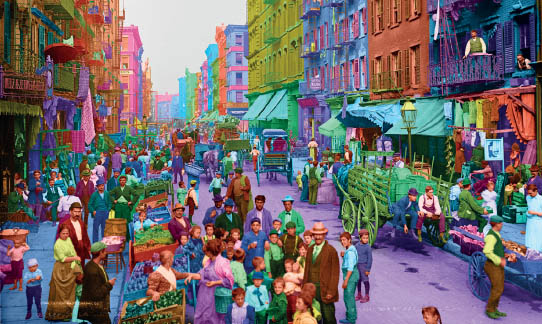

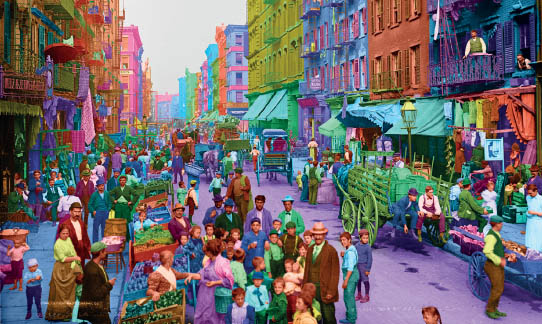

Mulberry Street, New York City, USA (Detroit Publishing Co. / Library of Congress) pp. 138–139

In 2016, New York was the first place in America I had the good fortune of visiting in my adult life. I was working with Wolfgang on an exhibition and I dragged History as They Saw It researcher Deborah through the rain to get a shot of the exact angle and location from which this photograph was taken. The original may have been taken on a ladder or horse cart; the best I could do on that cold, rainy day in New York was to balance one foot on top of some street railings.

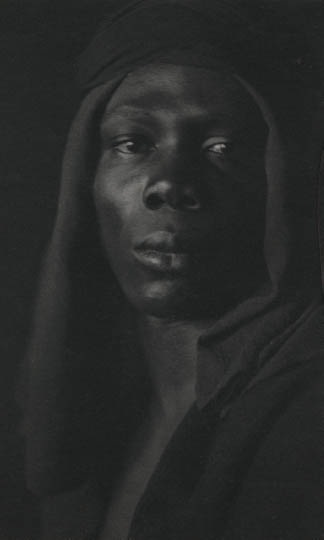

USA (Fred Holland Day / Science & Society Picture Library / Getty) pp. 140–141

The cropping and lighting of the photograph go beyond historical posterity and into fine art. I’ve sought to maintain the simplicity and allow the lighting to do the work.

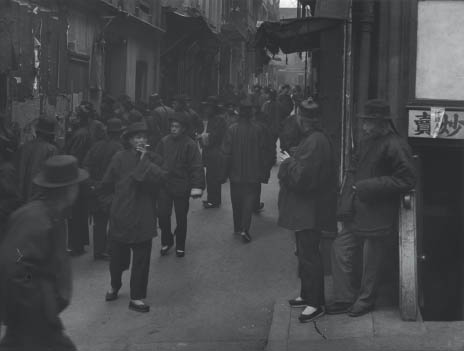

Street of Gamblers, San Francisco, California, USA (Arnold Genthe / Library of Congress) pp. 142–143

Some of the buildings still exist today and we could use them as color references, alongside photographs of markets in Hong Kong and China. Shots like this, featuring little color variation, are technically difficult. Achieving fifty shades of black convincingly is a challenge.

Montparnasse, Paris, France (ND / Roger Viollet / Getty) pp. 144–145

The stone building seen in this photograph no longer exists; it was demolished and redeveloped in the late 1960s. The train itself is a steam locomotive No. 721 (a type 2-4-0, French notation 120) hauling three baggage vans, a post van and six passenger carriages, painted in the operating company’s livery.

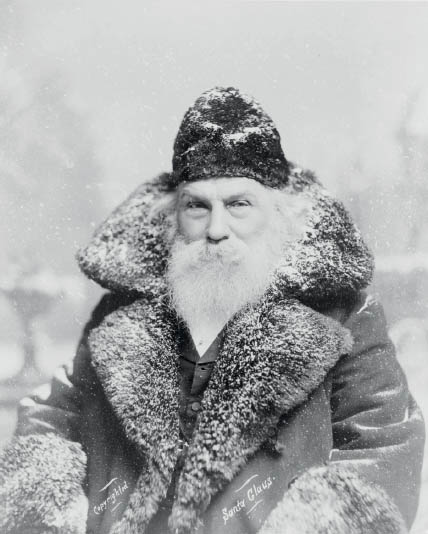

USA (Unknown / Library of Congress) pp. 146–147

The shot is characteristically over-exposed, like many of its era, to emphasize the caucasian skin tones. The ‘snow’ was most likely to have been white paint, flicked on with a brush.

Athens, Greece (Unknown / School of Archaeology, University of Oxford) pp. 148–149

The expansive background is now unrecognizable in modern Athens. It is filled in with rows of apartment blocks and modern infrastructure, though the numerous tourist photographs of the site indicate the color of the ground and, indeed, of the columns themselves.

Southwark, London, UK (Unknown / English Heritage / Getty) pp. 150–151

We sourced the numerous ships and skiffs lurking in the background from contemporaneous paintings of the 1880s.

Johnstown, Pennsylvania, USA (George Barker / Library of Congress) pp. 152–153

The photograph seems so improbable that it resembles a movie set. We used examples of painted houses of the period. The lack of sharp shadows indicated that the photograph was taken on an overcast day, adding to the dystopian landscape.

Champs de Mars, Paris, France (Roger Viollet / Getty) pp. 154–155

Due to the increased blue sensitivity of the photographic emulsion used in the image, the sky appears very washed-out, but the lack of cast shadows in the photograph suggest an overcast day. We used several paintings and picture postcards of the Exposition site as reference for the background buildings and could sample the stonework of Port de la Bourdonnais on the Seine riverbank, under construction in the middle of the photograph, from contemporary photographs.

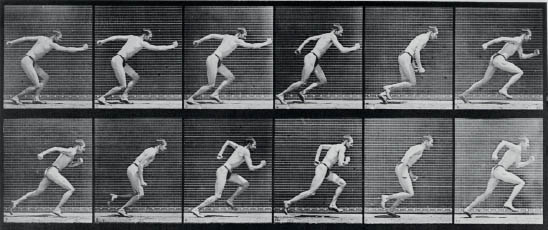

University of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania, USA (Eadweard Muybridge / Library of Congress) pp. 156–157

There are a few more photographs showing Muybridge’s elaborate rig at the University of Pennsylvania, from which these photographs were derived for the locomotion series. The human subjects were generally almost nude.

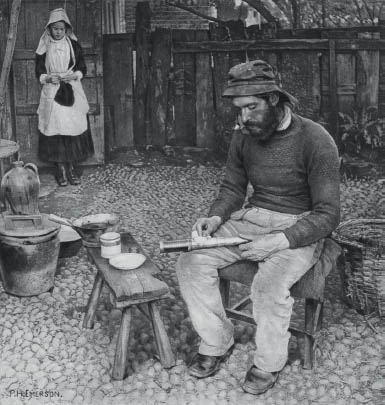

Norfolk, UK (Peter Henry Emerson / Royal Photographic Society / SSPL / Getty) pp. 158–159

The posing, composition and relief detail on this photograph suggest a Dutch painting rendered in oils, rather than a photograph. My favorite detail is the small, white clay pipe the subject is using whilst he goes about his work.

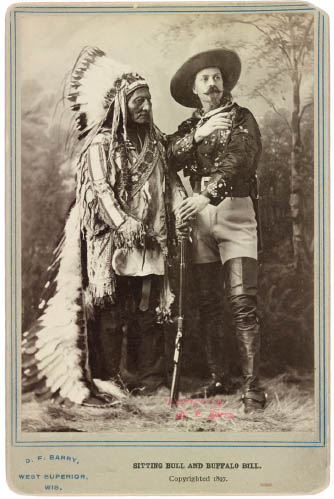

Montreal, Quebec, Canada (William Notman / David Francis Barry / Library of Congress) pp. 160–161

Sitting Bull’s braids are wrapped, possibly in fur. Many of the clothes in this photograph still exist in museums. Cody wears beige wool riding pants, with seven mother-of-pearl buttons on the lower leg. Strange as it may seem to our eyes, many of the backdrops used in Victorian photographic studios were black and white. Prior to the turn of the century, color photography was the preserve of only a handful of scientific pioneers. Coloring a backdrop for a monochrome photograph was a waste of time and money – though, for postcards issued using the image, the scene would be hand-tinted.

London, UK (Unknown / London Stereoscopic Company / Getty) pp. 162–163

The original plate of Mrs. Frampton has extensive fracturing and flecking, all of which it was possible to repair. Her clothes and her hair appear to be competing with each other for opulence and lustre. The coloration of the carpet, and indeed her clothes, were inspired by comparable museum objects – though my research has yet to surface who Mrs. Frampton was, or Mr. Frampton for that matter. The light on the surface of the mirror edge is particularly striking.

Paris, France (Albert Fernique / Library of Congress) pp. 164–165

This was a complex scene to do. The interplay between the darkness of the workshop and the natural light (in an era before electric lighting) made this a particularly challenging photograph, compounded by the lack of mid-tone detail. The recognizable elements of the statue in the background are plaster cast references. The wooden molds are visible in the foreground over which the copper was beaten to form the shape.

Montmartre, Paris, France (Unknown / Keystone France / Getty) pp. 166–167

There are several contemporary color photographs taken from the same vista, although not the same location, which provided a good overall reference. As many of the buildings in the foreground and background exist, everything from tourist photographs to Google Street View was used as a reference for specific examples.

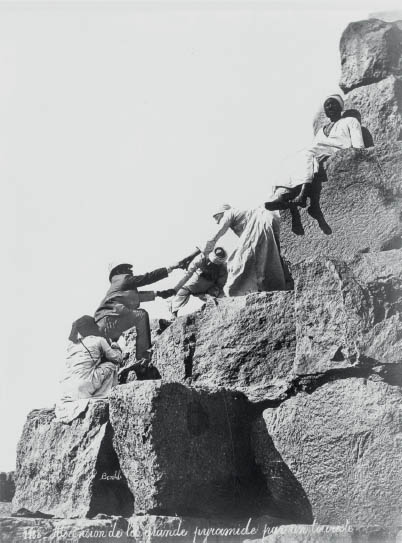

Giza, Egypt (Félix Bonfils / Library of Congress) pp. 168–169

The pyramids at Giza still remain one of the world’s most documented monuments, so finding accurate color references was a rather straightforward affair.

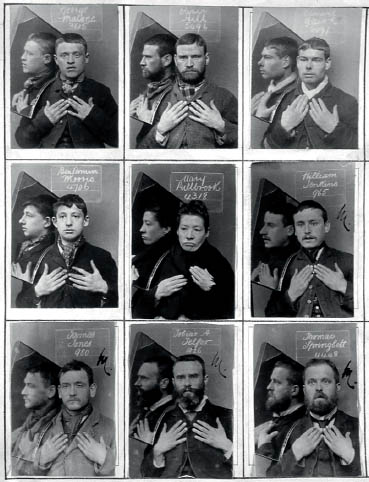

Wormwood Scrubs, London, UK (Science & Society Picture Library / Getty) pp. 170–171

Examples of clothing of the time were used for reference. One of my favorite details, which you can see if you look closely, is the shape of the mirror – curved to arch over the subject’s shoulder when the photograph is being taken.

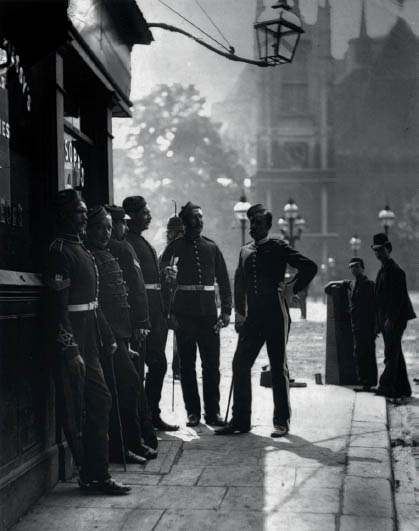

Westminster, London, UK (John Thomson / Science & Society Picture Library / Getty) pp. 172–173

Like many of the military units of the time, the dress uniforms of the British Army were very colorful and were distinct to differentiate between units. From left to right, the soldiers are: 6th Inniskilling Dragoons, a 4th Hussar, a recruiting sergeant on the staff, the Royal Scots Greys, a Dragoon Guard and a member of the 6th Dragoon Guard in stable dress.

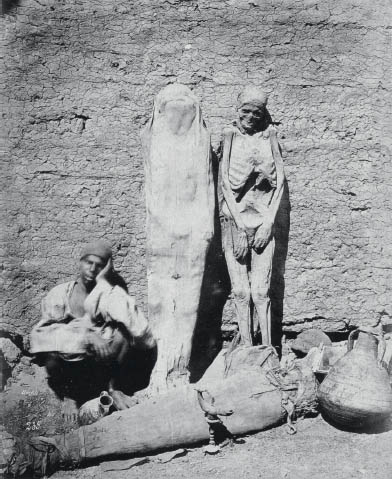

Egypt (Felix Bonfils) pp. 174–175

This is by far one of the most extraordinary images in the entire book for me, mainly due to the apparent indifference the dozing seller has towards his product – he could just as easily be selling fruit and veg. After working on the artifacts from the tomb of Tutankhamun, I had a great deal many more examples of color references, and the large blue Faience vase to the right made sense in the context of the photograph.

, ‘female martial artist’)

, ‘female martial artist’)Japan (Universal History Archive / Getty) pp. 176–177

The abolition of Japan’s isolationist Sakoku foreign policy during this period allowed the Port of Yokohama to flourish as a hub of foreign trade, thus introducing new Western technologies such as the camera. A number of Western-owned photographic studios operated in Yokohama, notably Beato & Wirgman, and the Japan Photographic Association (Stillfried & Andersen), whose commercial portraits and views of the country were in high demand both within Japan and beyond.

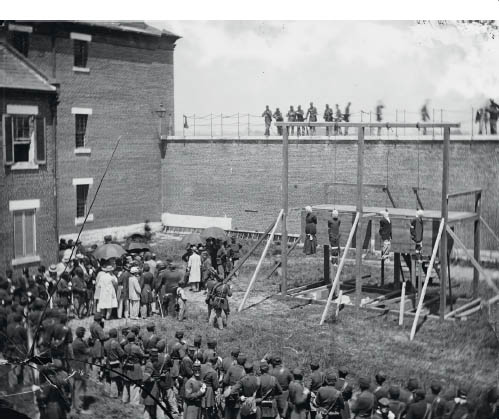

Fort McNair, Washington DC, USA (Alexander Gardner / Library of Congress) pp. 178–179

Bricks can be made in an almost-infinite number of shades, but what color were these bricks? Remarkably, a lone brick from the Old Capitol prison survives in a commemorative wooden box. The soldiers are wearing the uniform of the Union Invalid Corps, which existed from 1863 to 1869. A description of the execution tells us that the soldiers present were of Company F of the 14th Veteran Reserves. Improbably, the site of the hanging at Fort McNair is now a tennis court.

Turkestan, Russia (Unknown / Library of Congress) pp. 180–181

I am continually amazed by the vibrancy of the dyes and patterns used in clothing from different cultures. This man is likely to be wearing work garb despite the riot of color and patterning, which haven’t changed all that much over the last century.

Paris, France (Pierre-Louis Pierson / Getty) pp. 182–183

You would be forgiven for thinking that the Countess is affecting an elaborate face-mask, but in fact, if you look closely, you’ll see that she is peering through a picture frame.

Blackwall, London, UK (Unknown / Hulton Archive) pp. 184–185

We could reasonably assume the numerous work buildings in the background of the image supplied iron for the dry docks, as all timber ship construction had been phased out by the time this photograph was taken.

USA (St. Louis Taylor Copying Co. / Library of Congress) pp. 186–187

Remarkably, one of the Colt .45 revolver pistols still exists, and the color reference was supplied by a newspaper article about the gun going to auction.

Maryland, USA (Library of Congress) pp. 188–189

Sergeant Smith and his family lived most of their post-war lives in Mount Vernon, Rockcastle County, Kentucky. In the 1870 census, two other children are in the household as well. Although they look like twins, his daughters Mary and Maggie were, according to census records, a few years apart.

Atlanta, Georgia, USA (George N. Barnard / Library of Congress) pp. 190–191

Any paint on these buildings would have been applied before the Civil War began in 1861, and by 1864 would be faded. The buildings also show evidence of water damage, which can indicate mold. The building to the far right is the brick-built concert hall. Situated next to the railroad tracks, it was stained with the pine soot and smoke from the locomotives. While it can vary according to weather and season, Georgia earth is indeed an orangey-red in hue.

Gettysburg, Pennyslvania (Unknown / Library of Congress) pp. 192–193

This image entailed a full restoration from a damaged glass plate. Due to the plate being shot in orthochromatic, I needed to adjust the blue and red channels to compensate for the washed out sky of the original image. The clouds, I composited.

Paris, France (Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library) pp. 194–197

The engineer sappers of Napoléon’s Imperial Guard (Sapeurs de la Garde) were established by 1810. Sergeant Lefebvre’s (right) rank is denoted by the gold striping on the sleeve and epaulette loops of gold braid. In place of a helmet, the engineers wore a black felt hat called a shako, with brass chin-scales and scarlet plumes and cord. In addition to the Médaille de Sainte Hélène, Lefebvre also wears an insigne de La Société Philanthropique des Débris de l’Armée Impériale.

Officially known as the ‘2e régiment de chevaulégers lanciers de la Garde Impériale’, a light cavalry regiment in Napoéon’s Imperial Guard, the Dutch Lancers wore a distinct red uniform. It is possible that Monsieur Dreuse (left) was a Maréchal-des-logis, featuring red-and-yellow epaulettes rather than the standard blue-and-yellow.

Christ Church College, Oxford, England (Charles Dodgson / National Media Museum / Science & Society Picture Library / Getty) pp. 198–199

The background stonework and foliage suggest this wet-collodion portrait of Lidell was almost certainly taken in the Deanery Garden at Christ Church, where Alice and her two sisters would often play.

Crimea, Russia (Roger Fenton / Library of Congress) pp. 200–201

George de Lacy’s medals are housed at The Queen’s Own Hussars Museum within the fourteenth-century Lord Leycester Hospital in Warwickshire, England. The curator, Julian Spilsbury, was on hand to relate Lacy’s involvement in Washington DC, and expand on the histories of the different medals.

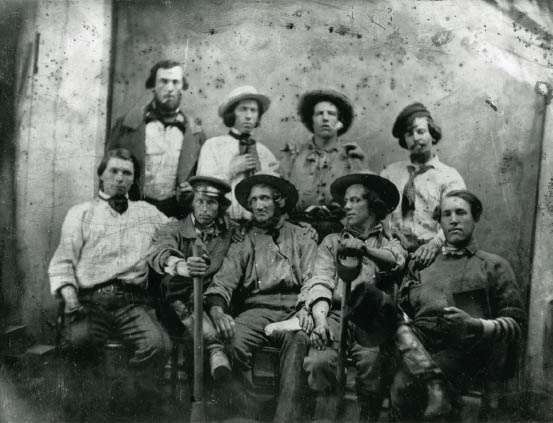

California, USA (California Historical Society) pp. 202–203

Wolfgang and I spent a considerable amount of time poring over real examples of clothing from the time – as well as replicas and other sources such as advertising – and debating likely colors for the outfits. It was tricky, especially given the orthochromatic effect of the photograph. The result, we hope, is an authentic expression of these pioneers in the photographic studio.

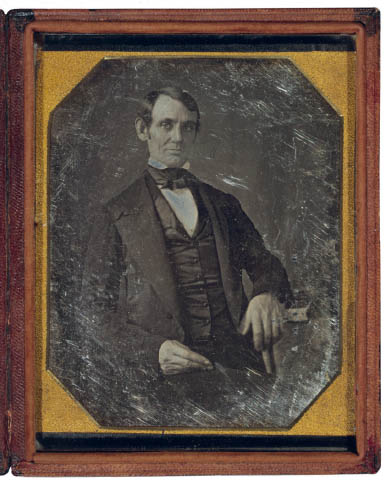

Springfield, Illinois, USA (Nicholas Shepherd / Library of Congress) pp. 204–205

There are extensive markings across the original plate, all of which I needed to eliminate. I made a very precise background swap around Lincoln, matching the lighting, and I also composited the heavily damaged parts of Lincoln’s right sleeve, and leg – Lincoln often sat in this pose – and the tablecloth.

Trafalgar Square, London, UK (Henry Fox Talbot / Science & Society Picture Library / Getty) pp. 206–207

Having the good fortune to live in London, I spent an afternoon trying to figure out the exact spot where the photograph was taken, which I believe to be the second floor of 64 Trafalgar Square (presently occupied by a franchised sandwich shop). I couldn’t get access to the building so I settled with climbing on top of a kiosk located fifteen feet away and took some reference shots looking towards St Martin-in-the-Fields. Technically, this was an extremely difficult image to do, due to the overall lack of definition. I was taken aback to find advertising even as far back as the 1840s was as vibrant as this, after discovering the painting A London Street Scene (1835) by James Orlando Parry.

176 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, USA (Robert Cornelius / Library of Congress) pp. 208–209

Robert Cornelius’s original plate is now heavily, and fundamentally, damaged. Often, digitally restoring an image to repair damage such as this can yield spectacular results. However, in this case, Wolfgang and I chose to take a different approach. We left the damage intact, and endeavored to place the color behind the damage. For us, the result has a special emotional resonance, which we could describe in the following way: Wolfgang and I are imprisoned within the camera – within our perspectives, filters and our assumptions about the past. Cornelius, seen in the past, appears grainy, damaged, indistinct. Yet in 1839, Cornelius was none of those things – he was sharp, clear, distinct. We peer through to his present, seeking to remove the damage from our own eyes.