Taking Up Instructions for Becoming

Rebecca Schneider

Gesture puts history in motion. Gesture extends iteration, jumping from one body to another, tracing one time in another time, one space in another space. Movement rolls through bone, flesh, coursing limb to limb—not unlike the way a beat is held in song or text, or the way an image passes across a field of vision, jumping frame to frame, screen to screen, or passing hand to hand. Movement, inevitable even in the seeming stone-still of statuary, shuffles events across time in intra-active waves of expressive form as stone meets flesh meets stone.1 Movement jumps from stone to human body and back, as in the nature self-portraits of Laura Aguilar in which Aguilar and a desert boulder trade in indistinguishability. It irrupts as mimesis among stick and insect or spin between architecture and human body and back.2 Movement takes place between paint and canvas and might jump again to intra-act with light at light’s own speed as painting is filmed, or taken up by a dancer, or translated into a poem. Movement percolates among water and stones in a creek bed or is held as 40,000 years of bated breath in the drip of a stalactite or the waveform of a negative hand stencil, moving in geologic time within the unlit bowels of the earth in Indonesia, in France, on the exuberant rock face of the Cueva de las Manos in Argentina.3

Jumping body to body, limb to limb, mouth to mouth, movement articulates variant registers of time that carry histories of intra-action and make intra-action anew. History, which is to say memory,4 courses along in curves and folds. It takes repercussive waveform, or tendrilous branch form, or irrupts in tuberous, rhizomatic explosions of call and response as response becomes call again.5 Movement moves. It is intra-action that finds its rhythms among animate and inanimate alike, rendering any definitive direction that would delimit a form and flow of time (such as forward and linear) impossible. Consider Emilio Rojas’s Instructions for Becoming in this vein. (See Figures 3.3.1 and 3.3.2.) Between human body and tree in this 2019 performance artwork subtitled Indio Desnudo, the weight of a limb might bend to the weight of a limb without distinction as to which limb bends first, which second, or where one limb begins and another ends. Human and nonhuman come undone in each other. As in Aguilar’s nature work, in this series Rojas’s intimate and queer laminations place precise jointure in question.6 Which first, which second, which human, which non are in limbo.

FIGURES 3.3.1 and 3.3.2 Emilio Rojas, Instructions for Becoming (Indio Desnudo), 2019. Amatlan, Mexico, from the series Instructions for Becoming. Courtesy of the artist.

Rojas grew up in Mexico and as a migrant moving in conditions of precarity between Mexico and the United States. Beginning this series while living and working in Chicago and wanting to experience something he describes as “return,” he literalizes the metaphor of roots in Mexico and simultaneously works to bend time. Rojas has written:

I’m thinking of trees as witnesses, and also both as landscape and beings which are interconnected through intricate root systems. I’ve been obsessed with trees since I was a little boy, so it’s not just returning to my roots as a migrant in the metaphorical sense but also as a child. (2019)

If “returning” implies movement from one time to another time, one place to another place, Rojas provocatively suggests intra-action, finding (his) roots in (his) limbs. Performance here is homage that branches in multiple directions—homage to the tree and the land and the artist’s migrant “roots,” and homage to artist Laura Aguilar with whose nature works Rojas’s Instructions explicitly resonate.

Instructions for Beco ming take up Aguilar’s gesture as if to respond in kind, like a wave of the hand is met with a wave in return, or instructions are met with reiteration. In this way, Aguilar’s call is recalled through Rojas (though she herself may be read not as origin but as responding to stone, just as Rojas responds to tree). In other words, Rojas’s performances take and pass instruction along a vast relay of branchwork, limb to limb, call to response to call. As photographs, limbs-become-image move as pixels of light. They branch out to find me where I encounter them even as I, in turn, pass them along in a gesture of transmission of my own (here in essay form).

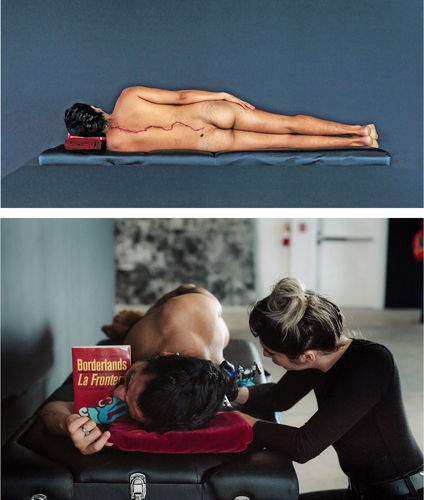

In another work ongoing since 2014, Heridas Abiertas (A Gloria), or Open Wounds (to Gloria), Rojas traces the long border between Mexico and the United States in blood (see Figures 3.3.3 and 3.3.4). Having carved the borderline into his back as an inkless tattoo, he reopens the wound annually, reopening, recarving the line so that it moves like a long branch, bending and bleeding in tandem with his spine. Across this piece and others, Rojas carries the work of Gloria Anzaldúa whose 1987 book, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, fundamentally called him to response. She writes: “The U.S.-Mexican border es una herida abierta (an open wound) where the third world grates against the first and bleeds. And before a scab forms it hemorrhages again, the lifeblood of two worlds merging to form a third country—a border culture” (1987: 3). Against his head, like a pillow, he literally lies upon her words, relying upon and relaying the queer woman-of-color feminism—the Chicana feminism—Anzaldúa set into gesture as he becomes or bodies forth the wound she articulates. One time in another time, one’s words in another’s mouth, Rojas literalizes the ongoing, reopening lives and afterlives of historical trauma that move in spinal time among us, limb to limb, reaching for redress.

FIGURES 3.3.3 and 3.3.4 Emilio Rojas, Heridas Abiertas (A Gloria). Courtesy of the artist.

Rojas’s Open Wounds brings to my mind an earlier, similarly decolonial work by the Anishinaabe artist Rebecca Belmore, who also uses performance as a mode to render literal the embodied tracks of historical dispossession. In Fringe (2007), Belmore’s back faces the camera/viewer. A long bleeding wound traverses her spine, moving laterally across the length of her torso. But what at first appears to be blood, on second look becomes a fringe of beadwork. What at first appears to be an open gash, on second look is on the mend—all of it rendered in make-up, thread, and beads. Oscillating between open and closed, the wound evokes both ongoing Anishinaabe heritage (beadwork) and, no less real, the ongoing trauma inflicted on indigenous peoples by the extractive expansionism of white settler colonial-capitalism (Figure 3.3.5).7

FIGURE 3.3.5 Rebecca Belmore, Fringe, 2008. Cibachrome transparency in fluorescent lightbox, 81.5 × 244.8 × 16.7 cm. National Gallery of Canada, Purchase, 2011. © Rebecca Belmore.

Less an open wound than a wound caught in the half-life process of becoming a scar, Belmore’s body meets her viewers in between times of historical trauma and what scholar Saidiya Hartman, writing of the slave trade, terms trauma’s ongoing “afterlife” (2008: 6). This is a wound both open and closed. Not entirely open and not entirely closed. It is also a wound dressed and redressed by performance. Belmore’s body is simultaneously performer, performance, and document. In fact, the work renders lines of distinction between performance and document moot. Belmore’s performing body is already a witness, as if document, standing as statuary or testament to the history it carries (the history that “bleeds” in the artwork of beads). It is important to note that in this work (as in Rojas’s) the camera and resultant image doesn’t do the documenting of some otherwise “live” performance, because the body is already, itself, both live and nonlive, bloody and beaded, animate and inanimate. The body and the performance are already document, just as the document performs. The photographic image is simply a means to jump form, to branch limb to limb and, thus, extend, as in waveform, body to body. The camera, that is, carries or amplifies or moves something of the body to pass among us, as a gesture moves or, perhaps, as a sound is carried forth from a body as a wave.8 The body is carried through photography as it would be through the gesture of a hand-wave, say, crossing space and time in a repercussive medium of call inviting response, address beckoning redress regarding the ongoing (after)lives of colonial dispossession. Even as the turned back is a mode of refusal, as in the performance photography work of Lorna Simpson, Belmore’s wound faces a viewer, simultaneously calling for and responding as body-jumping historical witness.9 This, too, is memory moving—limb to limb, spine to spine.

We might be moved to ask, without the promise of a precise answer: what of history passes in the jump among bodies, limb to limb? What of the animate and the inanimate, or of the living and the nonliving or the no-longer-living, intra-mingle in the imprecise form of performance-based gesture, the jump of movement, the pulse of pose? How does a gesture, like a body, open and close—move—across time, through media, in the ricochet of matter, among historical ruins, or toward otherwise futures? To think about this question, I’d like now to make an odd segue and take up a brief segment of mid-century European film. Though the move from explicitly decolonial work to work that roots around in European ruins might seem jarring, the jar is intended to loosen further questions and concerns, including the matter of the “animacy hierarchy” that Rojas after Aguilar is undoing (Chen 2012: 24). So, for a few pages, let’s imagine that we could sit together, now, and watch the entirety of Roberto Rossellini’s 1954 film Journey to Italy (Viaggio in Italia).

Sitting in a position of viewing, making space and time for the film to take place, darkening a room to allow the film light to wash across our faces as the images enter our eyes as the sound enters our ears—we are sp ectating actors’ one-time live performances preserved on film. What, if anything, of the “live performance” remains in the film, is carried by the film, enters our bodies through the medium of film and the light it rides? This is in part to ask, what do we see when we watch the no longer live, live? When one live replicates another live (as film light reflects across a spectating face, laminating face to face as it were), who is host and who is hosted? What passes limb to limb? This might also be to ask, of Rojas’s wound or Belmore’s fringe, what bleeds from one time to another time in the passage via performance across bodies in time? What of the live—or the live/nonlive interinanimation—jumps among bodies or beings across time?

Journey to Italy asks this same question in the narrative of the film by chasing something elusive that appears to pass among statuary—body to body—and to jump between human and stone. At first view, on the surface of the narrative, the film is “about” a dying marriage. A middle-aged white (northern European) couple, played by Ingrid Bergman and George Sander, are on a trip to southern Italy. They have inherited some property, it appears, that brings them to the country, but the film concerns a kind of creeping boredom or ennui that has rendered their marriage inert. In the film, we repeatedly see the actors, particularly Bergman, walking about in the ruins of the ancient Roman Empire. In viewing the film, we view Bergman viewing, because an inordinate number of shots are intent on the actress’s gaze, and often her general confusion about the wreckage of empire around her. But it’s not just her gaze. Her body, too, bends and contorts, her head barely stable upon her neck in some shots, as if craning her neck might address the wreckage in some way. We view Bergman viewing the detritus of empire—skulls in the catacombs, shards of once erect pillars, and crumbling fallout of monumental architecture. Or, more accurately, we watch the filmic traces of her viewing when she was alive to view.

In one scene, Bergman goes to an art museum in Naples, accompanied by a docent who points out various statues to her gaze. As she looks at the statues, curious almost hyper-theatrical expressions pass across her face and her head tilts or her shoulders shift in subtle ways that look as though she is literally taking the statue into her body. At one point, the film works to “capture” a gaze explicitly exchanged between seemingly inanimate statue and seemingly animate Bergman, as if animacy and inanimacy could jump across bodies interchangeable with each other. Watching the film, we seem to be spectating over Bergman’s mid-century shoulders as the gaze of the statue arrests her into stillness even as the statue itself moves across our viewing faces. Many of the statues are in ruins. At one moment the camera settles on a limbless Venus and jumps to Bergman’s affect-filled face—she looks as if she might prefer to run away but her own limbs have been amputated by the close-up. In fact, the relationship set up by the film—between the actress, the stone statuary, and we as viewers—is complex. Not only are we seeing Bergman seeing ruin/statuary, but we are also seeing her as ruin/statuary, and all of it—stone ruin and living actress—are, of course, seen as film—or seen as film sees, passed across our faces in the half-life of half-light. The stone statuary “sees,” the actress “sees,” and the viewer sees that seeing until a kind of vertigo sets in and Bergman has to literally run off screen. What is interesting to me here is not so much the focus on the gaze (a twentieth-century obsession), but on the way that Rossellini repeatedly brings to our contemplation the question of what is live and what is not, until eventually this question ricochets against us—the audience—prompting us to question our own status among the various varieties of detritus: The detritus of stone, the detritus of marriage, the detritus of film. At moments—still, silent, watching—we viewers may resemble more the statuary than the actress who walks (and then runs) among them. Among the ruins of stone, and in the light of film, do we all, together with Bergman, partake of the question: What does it mean to (be or become) live? What might becoming be?

Bergman and her semi-estranged husband visit Pompeii for a scene in which the conventional Western divide between live and nonlive further comes undone. In the ruins of natural disaster that is Pompeii, affect bounces back and forth between stone “remains” of the live (in this case the holes left in the shape of bodies in lava) and the privileged, white, heterosexual couple struggling with their dead, or almost dead, marriage. Journey to Italy bounces filmic scenes of animate-meets-inanimate, inanimate-meets-animate into our eyeballs and our ears. The light and sound are material—they enter our bodies as we watch—becoming live parasitically by living in/with/through another body as host, much as Mel Y. Chen might write of metal toxins, animate and inanimate mingling to the point of indeterminacy.10 So which is it? None of it is live or, as Rossellini suggests, all of it is live?11 Document or performance? As with the indeterminate line between Rojas’s body and the limb, or the slip of vision between blood and bead in Belmore’s Fringe, the difference becomes vital but undecidable. The movie presents a marriage (as it presents modernity, heteronormativity, and whiteness) literally “on the rocks” as the “living” couple are more devoid of affective connection to anything live (including each other) than are ancient stone effigies, pillars, skulls, and dust. Even by the end of the film, we are left unsure of whether Bergman and Sanders will resuscitate their marriage—and in fact we can only hope that they do not. At the close, nothing decided, a random carnival full of dark-skinned reveling Italians sweeps the whiter couple up in their ecstatic, pulsing crowd, reminding the viewer that the film is indelibly steeped in modernity’s romantic and racializing primitivisms even as it, just possibly, poses some questions about the insufferability of modernity’s capital-colonial assumptions.

As mentioned previously, it may have seemed odd to have moved from the queer intimacy of Rojas’s and Belmore’s decolonial work to a mid-twentieth-century European film about white heteronormativity that roots, and perhaps fetishizes, the ruins of ancient Rome. And yet, the ongoing afterlives of empire are perhaps shared topics across these works, though touching on privilege and dispossession differently. I think about this as I walk to work on my campus in Providence, Rhode Island, in the twenty-first century. To get to my office to write this chapter, I walk beneath a monumental triumphal arch that leads me onto an open yet enclosed campus green (see Figure 3.3.6). The arch stands on land that, like the whole of the state, is Narragansett territory. Thus, the when, where, and who of my daily walk are populous, composed of syncopated times, places, peoples, and things. Signatures of supposedly bygone Rome sit atop supposedly bygone Narragansett land. The resurrected classical “ruins” refuse the myth of their disappearance and perpetuate the ethos of “triumph” on and as the so-called “new” world. One time laminates another time; one place cites another place. Ancient Roman and Narragansett territory, both supposedly bygone, are both clearly intrainanimate (or the symbol of triumph would not be necessary).12 The arch conducts me through its liminal passage as if to say, in essence, “walk this way.” Though I am scripted into position by the monument and the histories of European expansion that it reinscribes, what other possibilities might the passageway pronounce? If I listen against the grain of expansive triumphalism in the shape of the arch, what else might I hear—of other genres of being human, other lifeways, other modes of becoming live? (Wynter 2015: 31).13 That is, might the stones themselves sing of alternatives if we learn to listen? Might they be acknowledged to gesture to the hole left in their quarry and perhaps articulate an elsewhere or an otherwise to the remarkable myopia of “triumph”?

FIGURE 3.3.6 Soldier’s Arch, Brown University. Photo credit: Nick Dentamaro for Brown University.

In What is Latin America, Walter Mignolo raises an open question about whether the degree to which we live in the twenty-first-century, late-capitalist “developed” world is the degree to which we have been “globalatinized” or subjected to globalatinization through Christianity and the colonial-capitalism that followed in the wake of conquest.14 Many habits, gestures, words many of us use, and architectures we inhabit circulate in the ongoing gyre of empire and reperform/deperform bits of empire’s gestic jetsam. To the degree that we reperform those habits, those words, those architectures, we are not only living in ruins but also living as ruins—the living ruins of empire’s exploitive disproportion. Of course, and importantly, the movements and gestures of those who have been colonized, enslaved, exploited, or otherwise unwillingly subjected to empire circulate and recirculate as well, moving inexorably as “the past that is not past” (Sharpe 2016).15 But as Rojas’s and Belmore’s decolonial works makes clear, though globalatinization may be a wound that runs along the spine to fuse (or be refused) with movement, nevertheless in time globalatinization will have failed.

In this vein, and in the shape of a near dead marriage between miserable white elites, it is interesting to consider what Journey to Italy suggests—that the ruins of white Western empire include the living. Living ruins, Bergman and Sander still attempt, in zombie form, to walk this way. That is, Bergman tries to keep walking until—just perhaps—her own body rebels against the ruse of triumph, the myth of productivity, and the (heteronormative) reproduction of the capital relation that her failing marriage seems to exemplify. Flickering across our faces, the film suggests she might (but only might) leave her dubious inheritance uncollected. Perhaps the hope of the film is that the songs the stones sing, even in the cracks and rubble of crumbling monuments they support, might gain in volume to somehow be heard over the thrall to ownership and mastery that “triumph” assumes. Somehow, in the mischievous smile of a crumbling statue, for example, might reside alternatives to empire’s monumentality and instructions of becoming otherwise.

In 2018, Rebecca Belmore made a journey to Greece for Documenta 14. Her piece for the exhibition, Biinjiya’iing Onji (From Inside), was a refugee tent carved out of white marble. As part of the exhibition situated in the landscape, the marble tent was located on Filopappou Hill, positioned to overlook the Acropolis with the Parthenon at its top and the Theatre of Dionysus at its base. To sit inside the tent, as the sculpture clearly beckons a body to do, is to make the tent a stage like the theater it faces. To enter the tent or to stand with it and see what it sees is twofold and complex. It is both to be contained by white marble and the cultural significance that such classical “whiteness” manifests, but it is also, and paradoxically, to take up the view from precarity, to adopt, across the body, the position of a refugee or a migrant and to look at the Parthenon as a refugee might view the legacies of Western empire and the ongoing urgencies of empiric colonial-capitalism that have rendered so many dispossessed. The work, rendered in marble, may itself be a monument, but it is one that, in Julia Bryan-Wilson’s words, “partakes of a counter-monumental vocabulary which we might understand not only as a grammar born in the aftermath of trauma, but also a minoritarian resource for those speaking back against human rights violations and structural racism” (in Steyn 2018: n.p.). The both/and aspect of the work renders it undecidable, like reopening a wound. Ready to jump, to move, it is pitched (like a tent) at the intersections of performance, sculpture, and embodied activism.

Coda

Belmore has said that many people look at Fringe and see a corpse. That may be, she says, but for her that body is still life, healing in some way, resurgent, “on the mend.”16 To me, at third view, the wound begins to look like a wing. I take up Rojas’s Instructions for Becoming again and think of his limbs held in limbs.

The tree I’m climbing is the medicinal tree known “scientifically” as Bursera Simaruba, commonly known as Indio Desnudo (Naked Indian), because it sheds its bark as a way of getting rid of parasitical/simbiotic species, so its barren and it looks naked. (Rojas 2019)

I can almost hear the wind as the performance lifts, like shedding bark, into and out of my hands.

NOTES

1. I take the word “intra-active” from Karen Barad (2003: 803).

2. See Laura Aguilar (2015). Another example of human and nonhuman mimesis is Valie Export’s Korperconfiguren, or “body configuration” photographs in which her body and architectural objects such as stone steps or traffic medians shape-shift with each other. Humans are not required of course. The example of stick and insect is manifest in the scholarship of Roger Caillois. In his provocative 1935 essay “Mimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia,” surrealist Roger Caillois wrote compellingly if enigmatically on the power of copying, situating mimesis as mutual displacement. To my reading, he invoked a widespread cross-creativity where living and nonliving engage in mutual “photography.” See Caillois (1935); and also Schneider (2018a) and Taussig (1992).

3. On negative hand stencils created by “prehistoric” humans around the world, see Schneider (2018b).

4. History and memory are generally considered in distinction to each other, much like document is considered, still, in distinction to live performance. But both could be said to be modes of each other—ways of holding or telling or moving one time into, through, or with another time. Imperial determinations of what cultural modes constitute memory (often considered embodied, ephemeral and constituting “repertoire”) and what modes constitute history (often considered narrative, image, or object based, archival, and even monumental) have been vexed and riddled with privilege and disprivilege along the lines of gender and race. The history/memory line is a ruin of colonialism that, like a bloody border in Rojas’s work, continues to haunt sedimented distinctions between performance and document that this chapter aims to blur. See Taylor (2003) and Schneider (2011).

5. For a theory of gesture that explores call and response in greater depth, see Schneider (2018b).

6. On the “queer intimacy” of human and nonhuman or inhuman see Mel Chen (2012: 1–12, 114). On Aguilar and the queer inhuman see Mel Chen and Luciano (2015: 183–208).

7. Throughout this chapter, I follow Glen Coulthard (2014) and hyphenate colonial-capitalism to underscore the connection.

8. Belmore has worked on waveform with her piece Wave Sound, 2017.

9. See the special issue on “Performing Refusal/Refusing to Perform” in Women and Performance (Mengesha and Pradmanabhan 2019).

10. In the film there is a liveness, a livingness, that irrupts as nonhuman. In fact, the liveness of Bergman’s body-in-relation occurs acutely in relationship to her encounter with the inanimate—or that which is conventionally given to be inanimate: stone. It’s rendered explicit, of course, in the human-shaped sculpture, but the liveness is broader than anthropocentrism can delimit. It is suggested throughout the film by landscape, architecture, and rubble itself. But again, there is no stone. There is no living actress. There is only film—light and screen that play or perform across our bodies as we watch. Elsewhere, I have discussed this as “intrainanimacy” (Schneider 2017).

11. When asked by Eric Rohmer and François Truffaut about Journey to Italy in a Cahiers du Cinéma interview, Roberto Rossellini described the importance of Naples: “that strange atmosphere which is mingled with the very real, very immediate, very deep feeling, the sense of eternal life,” in Jim Hillier (1985: 211). On the neovitalism of some strands of new materialist criticism as it impacts performance theory, see Schneider (2015).

12. On the triumphal arch and legacies of conquest in the “new world,” see Carolyn Dean (1999).

13. Like Sylvia Wynter, Elizabeth Povinelli argues for writing of modes of human rather than human per se. The white “settler late liberal” mode of human that has retroactively and nostalgically fetishized its roots in ancient Greece and Rome even while romanticizing indigeneity as lifeways disappeared to modernity has been, Povinelli reminds us, a mode that is radically exploitive of some humans over other humans, some humans over animals, and some humans over the earth, air, and water that holds us all. “We” have not always been settler colonial capitalists. And in fact, “we” (among so-called humans) are not all so today. She writes: “I stake an allegiance with my Indigenous friends and colleagues in the Northern Territory of Australia. Here we see that it is not humans who have exerted such malignant force on the meteorological, geological and biological dimensions of the earth but only some modes of human sociality. Thus we start differentiating one sort of human and its modes of existence from another” (2015: 16).

14. See Walter Mignolo (2005: 92). I take “globalatinized” from Derrida, who Mignolo also references (Derrida 1998: 11).

15. Sharpe is explicitly referencing the wake of the Middle Passage and the circum-Atlantic slave trade.

16. Belmore, http://www.rebeccabelmore.com/fringe. On resurgence, see Simpson (2011).

References

Aguilar, Laura (2015). “Human Nature.” Boom 5, no. 2. Available at: https://boomcalifornia.com/2015/08/11/human-nature.

Anzaldúa, Gloria (1987). Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books.

Barad, Karen (2003). “Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter.” Signs 28, no. 3: 801–831.

Bergs, Steyn (2018). “Material Relations: Interview with Julia Bryan-Wilson.” Open!: Platform for Art, Culture and the Public Domain. May 29, 2018. Available at: https://onlineopen.org/material-relations.

Caillois, Roger ([1935] 1984). “Mimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia,” translated by John Shepley . October 31: 12–32.

Chen, Mel Y. (2012). Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Chen, Mel Y. and Dana Luciano (eds) (2015). Special issue: “Queer Inhumanisms.” Gay and Lesbian Quarterly 21, nos. 2–3.

Coulthard, Glen Sean (2014). Red Skins, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Dean, Carolyn (1999). Inka Bodies and the Bodies of Christ. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Derrida, Jacques and Gianni Vattimo (1998). Religion. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Hartman, Saidiya (2008). Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Hillier, Jim (ed.) (1985). “Interviews with Roberto Rossellini.” Cahiers du Cinema 1: 211.

Mengesha, Lilian G. and Lakshmi Padmanabhan (eds) (2019). Special Issue: “Performing Refusal/Refusing to Perform.” Women and Performance 29.

Mignolo, Walter (2005). The Idea of Latin America. London: Blackwell Publishing.

Povinelli, Elizabeth A. (2016). Geontologies: A Requiem to Late Liberalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Rojas, Emilio (2019). Personal correspondence, March 17.

Schneider, Rebecca (2011). Performing Remains: Art and War in Times of Theatrical Reenactment. New York: Routledge.

Schneider, Rebecca (2015). “New Materialism and Performance Studies.” TDR: A Journal of Performance Studies 59: 7–17.

Schneider, Rebecca (2017). “Intra-inanimations,” in Christopher Braddock (ed.), Animism in Art and Performance, 191–212. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Schneider, Rebecca (2018a). “Appearing to Others as Others Appear: Thoughts on Performance, the Polis, and Public Space,” in Ana Pais (ed.), Performance in the Public Sphere. Lisboa: Centro de Estudos de Teatro and Per Form Ativa. Available at: https://performativa.pt/.

Schneider Rebecca (2018b). “That the Past May Yet Have Another Future: Gesture in the Times of Hands Up.” Theatre Journal 70, no. 3: 285–306.

Sharpe, Christina (2016). In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Simpson, Leanne (2011). Dancing on Our Turtle’s Back: Stories of Nishnaabeg Re-creation, Resurgence, and a New Emergence. Winnipeg: Arbeiter Ring.

Taussig, Michael (1992). Mimesis and Alterity. New York: Routledge.

Taylor, Diana (2003). The Archive and the Repertoire. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.Wynter, Sylvia (2015). On Being Human as Praxis. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.