David Joselit’s After Art is devoted to analyzing the scale and speed at which images proliferate today, as well as the ways in which these trajectories have been taken up in recent artistic practice. In the midst of a discussion of the work of Pierre Huyghe, an artist who has dealt extensively with issues of intellectual property, a footnote with an at best tenuous relationship to the body of the text rather perplexingly deems a discussion of copyright beyond the scope of the book.1 As the body of laws that serves to regulate the scale and speed at which images may legally proliferate, one might assume that considerations of copyright would play a significant role in Joselit’s text. But it is this exclusion that allows Joselit to set up what is perhaps the book’s grounding opposition, between what he terms “the free ‘neoliberal’ circulation of images” and a “fundamentalist” attitude that “posits that art and architecture are rooted to a specific place.”2 There is no question about where Joselit locates his own allegiances in this conflict: for him, neoliberal circulation proposes exciting new forms of connectivity, while the fundamentalists cling to the rather unfortunate privileging of discrete objects and fail to recognize that contemporary existence is characterized above all by ecstatic mobility. Despite the centrality of the logic of privatization to the economic philosophy of neoliberalism, the privatization of visual culture through the aggressive enforcement of copyright nowhere enters into Joselit’s application of this term to the realm of images.

The absence of a discussion of copyright in After Art might be explained by copyright’s limited role in regulating the circulation of images in the artistic context. The artificial scarcity of the editioning model tends to ensure reproducible artworks remain outside the channels of mass distribution (at least officially), with the result that recourse to copyright is not necessary to control circulation. The art context tends to be more about copy rites than copyrights, regulating image mobility by conventions that are developed internally and that function very differently from their mass cultural counterparts. Yet copyright’s absence in Joselit’s discussion takes on a strategic importance because it allows him to map an opposition of present/past onto that of neoliberal movement/fundamentalist stasis in order to make an epochal claim for ours as a time of unfettered transmission and networked relationality. A consideration of copyright law, and particularly the extent to which it has rigidified over the last twenty years, would temper the apparent freedoms of neoliberal circulation Joselit values by introducing to the discussion a pervasive form of control that is irreducible to the fundamentalism he so easily dismisses as old-fashioned. During this period aggressive legislation and prosecution, copyright enforcement robots, and digital rights management systems have transformed a set of laws originally formulated to stimulate creativity into a framework for profit-motivated policing. In particular, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) of 1998, passed by a unanimous vote in the United States Senate, heralded a new era of extremism.3 But for Joselit an assessment of the realities of copyright in the post-DMCA context would reveal its ability to render sclerotic the connective circuits he holds so dear.

Such an affirmation of unbridled circulation exemplifies a pervasive tendency among artists and critics engaging with the contemporary mobility of images, though it is seldom expressed as explicitly as it is in After Art. It is a tendency that cuts across a wide variety of aesthetic and political investments to celebrate promiscuous circulation as the sine qua non of contemporary visual culture, often implicitly replaying the long-standing but spurious associations of digital technology with freedom, democracy, and user autonomy. But just as it is necessary to recognize the Internet as a technology of both freedom and control, so, too, is it imperative that the contemporary circulation of images is understood as both more unmoored and more restrained than ever before. In 1994 John Perry Barlow, founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, wrote that “intellectual property law cannot be patched, retrofitted, or expanded to contain digitized expression any more than real estate law might be revised to cover the allocation of broadcasting spectrum”—yet this is exactly what has occurred.4 Although such revisions are certainly not watertight, they cannot be ignored. Moreover, this development is not particularly surprising; after all, the history of copyright legislation is nothing other than the history of grappling with technological innovations that challenge it. As Martha Buskirk has noted, “The initial establishment and the subsequent development of copyright principles should be understood as a series of responses to the potential for disruption inherent in various new forms of technology.”5 The possibilities of digital circulation have been matched by the adoption of increasingly aggressive intellectual property legislation. Contrary to the still pervasive mythos of digital liberation and the technological ease of copying, not everything is available, not everything is archived, and not everything is free for reuse.

Contemporary artists such as Richard Prince and Luc Tuymans have recently been charged with copyright infringement for creating works based on appropriated photographs. The case against Prince concerned his Canal Zone series of paintings, which incorporated photographs taken by Patrick Cariou from his 2000 book, Yes, Rasta. After Prince was initially found guilty of infringement, a 2013 appeal overturned the decision but reserved the right to further review five paintings to ensure that their use of Cariou’s photography qualifies as fair. In the case of Tuymans the artist used a copyright-protected photograph taken by Katrijn van Giel of the Belgian politician Jean-Marie Dedecker as the basis of a painting he named A Belgian Politician (2011). The court rejected his claim of parody, fining him €500,000—apparently tied to the estimated value of the painting. As art lawyer Daniel McClean has noted with reference to these decisions, it is striking that most copyright disputes in twenty-first-century art have been brought by photographers against artists. For McClean this signals that such proceedings are about “not just economic remuneration, but authorial recognition. In reproducing the readymade image of the photograph without recognition of the photographer as author, artists have tended to occlude its provenance.”6 This is a very persuasive claim: it may be that appropriation stings most when it occurs but is not clearly coded as such. But certainly the blue-chip status of artists recently involved in high-profile suits—besides Prince and Tuymans, add to the list Jeff Koons and Andy Warhol—suggests that financial remuneration is an additional contributing factor.

Within the sphere of artists’ moving image, practices of recycling have a long history and have been exceedingly common in recent years. In the case of uneditioned work the level of economic remuneration and the lack of authorial recognition of appropriated material present in the Prince and Tuymans cases tend not to be at play. Moreover, the works generally circulate in niche contexts, all of which helps explain why such practices have proliferated without legal intervention from rights holders.7 Though more money may be at stake with editioned works, their even more tightly controlled circulation and fine art imprimatur serve as protection. Indeed, the prevalence of repurposed images within such practices has frequently been taken as evidence of the new freedom and availability of moving images. For example, in his highly influential book Postproduction—Culture as Screenplay: How Art Reprograms the World, curator Nicolas Bourriaud writes that “contemporary art tends to abolish the ownership of forms, or in any case shake up the old jurisprudence. Are we heading toward a culture that would do away with copyright in favor of a policy that would allow free access to works, a sort of blueprint for a communism of forms?”8 Nowhere does Bourriaud address the contradiction that the very works of art he believes “abolish the ownership of form” are distributed as contractually regulated limited editions. Pierre Huyghe’s The Third Memory (1999) may make use of footage from Sidney Lumet’s Dog Day Afternoon (1995), but this “blueprint for the communism of forms” was offered for sale in a limited edition of four, its circulation tightly controlled. The artist’s Blanche Neige Lucie (1997), a 35 mm film detailing performer Lucie Dolène’s legal action against the Disney Corporation to regain the rights to her own voice, was once available on YouTube but was removed at the artist’s request. Contemporary art may be replete with practices that assail notions of authorship and intellectual property, but its market would fall apart without them. There is, then, a distinct incongruity between the understanding of image circulation thematized in these works and the distribution circuits they inhabit.

Despite some significant engagements with intellectual property issues, most artists and scholars emphasize the possibilities of reuse and resignification of proprietary materials over any interrogation of the increasingly strict legal controls that have been instituted in an effort to restrict unsanctioned uses. Neither of the most prominent book-length studies of the found-footage film in English—Jamie Baron’s The Archive Effect: Found Footage and the Audiovisual Experience of History and William Wees’s Recycled Images: The Art and Politics of Found Footage Films—includes discussion of the legal dynamics of such redeployments.9 At best, the repurposing of existing cultural forms may be understood as an implicit critique of recent developments in copyright law. But less generously, one might say that in neglecting to consider the various controls to which images are subject today, such works risk perpetuating a fantasy of free circulation. Christian Marclay’s disinclination to consider copyright issues during the production of The Clock (2010) was well publicized, with the artist stating, “If you make something good and interesting and not ridiculing someone or being offensive, the creators of the original material will like it.”10 While Marclay indeed ran into no trouble for his use of hundreds of clips in The Clock, there are many other criteria in addition to those of “good” and “interesting” that might be said to be responsible for this outcome, including the artist’s preexisting prestige, his decision to exhibit the work exclusively in art spaces, the adoption of the limited-edition model of sale, and the absence of any critical relation to the source material used within it. In his false opposition between “interesting” and “offensive” art Marclay dissimulates the fact that copyright very much does remain an issue for artists who may lack his cultural capital, choose to adopt different distribution models, or want to repurpose copyrighted material to political or critical ends. Furthermore, as Richard Misek has noted, although The Clock is “premised on the existence of a shared cinematic imaginary,” the strict policing of its circulation through the limited-edition model is “not only a cultural appropriation but also an economic appropriation” that betrays the share-alike ethos that made the work possible and, in its place, reinscribes private ownership: “Marclay took thousands of copyrighted clips and effectively said, ‘These are mine.’ Having expropriated them from their copyright holders, he then reappropriated them for himself.”11 Pace Bourriaud’s claims for a “communism of forms,” this is not an inspiring testimony to the status of the cultural commons.

Beyond this logic of privatization, the refusal to confront pressing questions of intellectual property constitutes a tragically missed opportunity. The easy assumption of freedom of reuse within the art context occurs precisely at a time when the vernacular redeployment of existing images is being policed and monetized by rights holders like never before. By minimizing discussions of copyright, whether within the work or in the discourse surrounding it, artists forgo a chance to intervene in or at least draw attention to the increasing privatization of visual culture. Eli Horwatt has remarked on the “utopian discourse” that sees practices of digital remixing as inherently critical; in addition to this it is necessary to highlight another equally utopian discourse that celebrates the unimpeded movement of images rather than recognizing that new forms of freedom have been met with new forms of control.12

Against this prevailing attitude, Eileen Simpson and Ben White’s archival footage project Struggle in Jerash (2009) is significant for the manner in which it both partakes of the new mobility of digital images and foregrounds the dangers of increasingly aggressive copyright legislation. Rather than buy into specious assertions of the free mobility of images after digitization, Struggle in Jerash stages an astute consideration of the various constraints—not just legal but also financial and infrastructural—that regulate the circulation of cultural products across time and across formats. It departs from the montage aesthetic that characterizes so much of the history of recycled images to instead appropriate an existing work in toto to ask, “Who owns a film?”13

The First Film

Simpson and White are best known as the initiators of the Open Music Archive, a collaborative project whose aim is to find, digitize, and distribute audio recordings that have fallen out of copyright. The pair has worked extensively with issues of intellectual property and archival material, most often in the domain of sound. Invited in 2008 to a residency at Makan House in Amman, Jordan, to undertake a project concerning the resources of the public domain in that country, the artists’ research led them in a slightly different direction: to the cinema. Specifically, they became interested in the 1957 film Struggle in Jerash (Sira’a fi Jerash), directed by Wasif al-Shaikh, which had fallen out of copyright that year (figure 4.1). Set in Jordan and Jerusalem and made by a group of independent filmmakers of Palestinian descent, Struggle in Jerash was the first feature film produced in the country, which had gained independence from Great Britain just over a decade earlier, in 1946.

FIGURE 4.1 Still from Struggle in Jerash (1957/2009). Courtesy of Eileen Simpson and Ben White, (cc) Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0.

Most films produced in Jordan have been international productions interested in using its desert landscapes for location shooting. Jordan’s Royal Film Commission, founded in 2003, lists only fifteen Jordanian films in its “Jordan’s Hall of Films” list, ten of which were made in 2007 or later; the other forty-seven are international films like The Hurt Locker (2007), Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), and Lawrence of Arabia (1962), in which the country often stands in for another location inaccessible to the filmmakers.14 When Captain Abu Raed (2008) was released as the result of a state-sponsored push to cultivate domestic production, the Jordanian film critic and historian Adnan Madanat became upset with those who proclaimed it to be the country’s first film. In response he published an article in Jordan’s al-Rai newspaper entitled “The First Film and National Identity”:

In the western Arab World, it was…foreigners who started film production, be it fiction or documentary. Such film productions were not considered First Films inasmuch as they were viewed as colonialist-era products. In other countries, such as Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan, First Films were purely local enterprises, albeit technically and artistically immature, made by enthusiasts who were passionate about cinema even though they have not fully mastered cinema production.

But not only did these pioneers not contend [sic] themselves with making the film; they manufactured their own production equipment and developed production techniques according to available recourses [sic].

This was the case for pioneering Jordanian feature film Struggle in Jarash [sic] (1957), which was produced, directed, filmed, and acted by local independents. Some worked as projectionists in movie theaters, some artisans, others welding technicians, projection repairmen. Those were some of the skills that were employed in manufacturing film development gear, printing and cutting hardware, and sound sync system for the film.15

It was through this article that Simpson and White became aware of the film, which combines the romance and gangster genres with elements of a travelogue. The film was heavily influenced by the Egyptian cinema of the time, in particular that of Youssef Chahine, who had produced two films with similar titles, Struggle in the Valley (Siraa fil-wadi, 1954) and Struggle in the Pier (Siraa fil-mina, 1956).

Madanat came across the film in the 1980s while researching a book on the history of Jordanian cinema. In the absence of an official archive Struggle in Jerash had no clear guardian. Madanat found that Mustafa Najjar, an assistant director on the film, possessed the only remaining 35 mm copy, which was in extremely poor condition. Madanat made a telecine copy of the print, which later went missing, making the low-quality VHS tape all that was left of a crucial text in Jordanian film history. Working from Madanat’s tape in collaboration with Jordanian artists and intellectuals, Simpson and White produced Struggle in Jerash, a project that unfolds the cultural history residing in this near-forgotten film by making use of two key components of the digital afterlife of commercial film releases: the DVD director’s commentary track and the market for bootleg DVDs. Struggle in Jerash appropriates a noticeably low-quality copy of a film historical text in its entirety and asserts a connection to an illegal form of distribution proper to the digital age—the market for pirated DVDs—in order to contest the privatization of images and the uncertain fate of the public domain.

Simpson and White digitized Madanat’s VHS copy and used the transfer as the basis of a new, sixty-minute work. The image-track of the video consists of the 1957 film played in its entirety. The picture is extremely degraded, both from significant damage to the original 35 mm print and from its transfer to VHS tape. There are numerous scratches and blotches of decay, and sometimes the analog video scan lines become visible, clearly indexing the travels of the image through time. Simpson and White’s intervention occurs on the soundtrack, which consists of the voices of twelve Jordanians who comment on what they see in the film. Giorgio Bertellini and Jacqueline Reich have described directors’ commentary tracks as “value adding paratexts” that “[expand] films’ authorial halo.”16 Inaugurated by the commentary the Criterion Collection produced for its 1984 laserdisc release of King Kong (1933), such extra features have traditionally served two primary functions: to regulate the meanings attached to the text through the reassertion of authorial control over signification and to generate revenue by producing a product for the collectors’ market that offers more than simply the feature film. As such, the director’s commentary track might be said to have a relationship to private ownership twice over.

Simpson and White turn this element of the digital circulation of moving images on its head (figure 4.2). On their Struggle in Jerash DVD the original 1957 film is included as a special feature (with English subtitles), while the commentary track occupies the main menu; text and paratext are inverted. Robert Alan Brookey and Robert Westerfelhaus have written that on the standard commentary track, “individuals involved in the film’s production are presented in the extra text as having privileged insights regarding a film’s meaning and purpose, and, as such, they are used to articulate a ‘proper’ (i.e., sanctioned) interpretation. This privileged positioning may be best understood as a return to ‘auteurism.’”17 Something very different happens in Struggle in Jerash: the contemporary spectators commenting on their viewing of the film occupy no privileged position in determining its meaning, nor do they serve to articulate a singular, sanctioned interpretation of the text. Often, they do not try to understand the text on its own terms but instead bring to it their own experiences.

FIGURE 4.2 Photograph of table for recording commentary track of Eileen Simpson and Ben White’s Struggle in Jerash (2009). Courtesy of Eileen Simpson and Ben White, (cc) Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0.

None of the individuals involved in the making of the film—nor anyone of their generation, for that matter—offers commentary. Rather, those who share their viewing experience do so in an effort to open, rather than to close, the possible meanings that one might attach to their country’s first feature. Hito Steyerl sees the poor image as endowed with a sociality: it “constructs anonymous global networks just as it creates a shared history” and “builds alliances as it travels, provokes translation or mistranslation, and creates new publics and debates.”18 Here this potentiality is borne out quite literally, as the rescreening of this forgotten film serves as the occasion for a discussion that ranges from questions of film technique to issues of national identity. White has noted that the group of individuals who comment on the film were not a representative sampling of the inhabitants of Amman but simply one group of people, those whom the artists met during their residency. He said, “It’s almost possible that another version could be made by someone else. In a way, this is just one potential iteration of a number of commentaries.”19 Through its polyphonic weaving of voices the video contests a notion of the film as private property over which a single individual might lay discursive or legal claim, understanding it instead as part of a shared cultural commons. In line with this approach the disc is distributed using the Creative Commons license Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0, meaning that the work may be reused or remixed for commercial or noncommercial purposes, provided that the derivative work credits the authors and adopts the same license in turn.20 Rather than simply flouting copyright law, then, Simpson and White draw on the resources of the public domain. They produce a transformative work that serves to enrich and extend the cultural life of the source text.

Purposeful Pirates

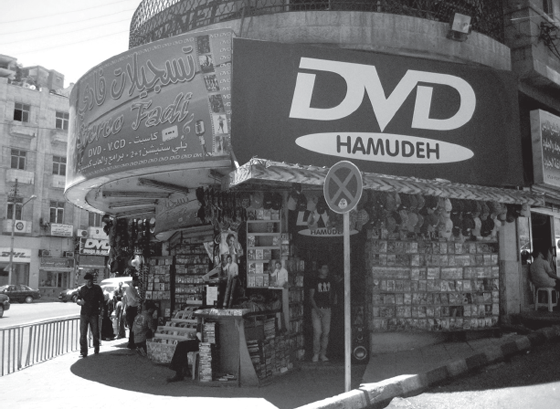

The second component of the Struggle in Jerash project reinforces this understanding of the 1957 film as a public good. Simpson and White reinserted the film into the most widely used distribution circuit for feature films in Jordan: the market for pirated DVDs. The Motion Picture Association of America estimates that the major American studios lose $6.1 billion to piracy each year, with 80 percent of piracy occurring outside of the United States.21 As Barbara Klinger writes, “Piracy has thus incited an economic, legal, and moral panic in Hollywood, causing pirated films to appear as monstrous transgressions of copyright laws.”22 In the Jordanian context, pirated films do not appear as transgressive but rather are the primary way that commercial films are distributed in the country (figure 4.3). Simpson described the pirate markets in downtown Amman as “the best archive in town,” a place where one might find a wide selection of American movies and television shows, as well as films from across the Arab world and beyond, on sale for one Jordanian dinar each.23 Simpson and White took their version of Struggle in Jerash to Hamudeh DVD, a pirate operation large enough to have multiple branches and a website (figure 4.4). Hamudeh produced a bootleg version of the film with a color photocopy cover sporting the Hamudeh logo and a blank-labeled DVD inside, and integrated it into its collection of films. The artists have also made it available for free streaming on Vimeo.

FIGURE 4.3 Box of DVDs of Eileen Simpson and Ben White’s Struggle in Jerash (2009). Courtesy of Eileen Simpson and Ben White, (cc) Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0.

FIGURE 4.4 Outside of Hamudeh DVD, Amman, Jordan. Courtesy of Eileen Simpson and Ben White, (cc) Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0.

This gesture reintroduced Jordan’s first film into wide distribution, using an unofficial form of circulation to return a part of the country’s audiovisual patrimony to its people in the absence of state-initiated efforts at preservation and dissemination. Steyerl writes that “poor images circulate partly in the void left by state-cinema organizations who find it too difficult to operate as a 16/35-mm archive or to maintain any kind of distribution infrastructure in the contemporary era.”24 In the case of Jordan such an organization never existed to begin with. Struggle in Jerash responds to this void while also speaking to another: the increasing emptiness of the public domain worldwide. Simpson and White’s determination to seek out and make use of the resources of the public domain occurs at a time when its very existence is in jeopardy. The Berne Convention requires that signatory states guarantee a copyright term of the life of the author plus fifty years, but states are free to pass legislation guaranteeing longer terms, and such practices are increasingly widespread. Lawrence Lessig has noted that in the United States, “from 1790 to 1978, the average copyright term was never more than thirty-two years, meaning that most culture just a generation and a half old was free for anyone to build upon without the permission of anyone else.”25 This is no longer the case. Successive extensions of existing and future copyrights and the abandonment of renewal requirements caused the average American term to triple between 1973 and 2003, from 32.2 years to 95 years.26 In the European Union, copyright extension legislation was passed in 2011 that extended the protection of sound recordings by twenty years to the author’s life plus seventy years. Copyright critics fear that such extensions could continue indefinitely, effectively sounding a death knell for the public domain.27

In Jordan, films are protected by copyright for only fifty years following the date of production. Thus, Struggle in Jerash, made in 1957, entered the public domain in 2007, while European and American films produced in the same year remain under copyright. As the public domain shrinks, Simpson and White’s project demonstrates how important it is to ensure that copyright terms remain limited. By working in a country that has yet to adopt major term extensions, they point to precisely what kinds of interventions are possibly being closed off to artists, scholars, and educators in jurisdictions that have. In this regard it is notable that Struggle in Jerash involves the appropriation of a film in its entirety, with minimal intervention on the part of the artist. Whereas fair use provisions might cover the use of small excerpts, this form of wholesale appropriation requires public domain material to be done legally. If Jordan had a longer copyright term, comparable to that of the United States or the European Union, Struggle in Jerash would have been an orphaned work, that is, a work that is still under copyright but commercially unavailable, with no copyright owner to be found. For archivists the most common response is to leave such works alone, for fear of unintentional infringement and possible litigation.28

As much as the recirculation of Struggle in Jerash can be seen as a gesture that makes manifest the losses to the public domain in Europe and North America through the extension of copyright terms, Simpson and White’s intervention takes on an added resonance for contemporary Jordan, a country currently undergoing a significant reconfiguration of its attitudes toward copyright and piracy as it emerges as an important intellectual property market in the Middle East. In 1997 and 1998 Jordan appeared on the United States Trade Representatives’ (USTR) watch list of countries with insufficient copyright legislation and enforcement. The 1997 report noted, “Jordan’s 1992 copyright law is cumbersome and falls far short of international standards in most respects. Any protection offered by the law is undermined by a lack of effective enforcement mechanisms and, as a result, piracy is rampant.”29 New legislation passed in 1999 ensured Jordan’s removal from the watch list and caused it to be singled out in the USTR’s report that year as a site of significant progress.30 Increased intellectual property compliance is key in stimulating foreign investment and, for Jordan, was necessary for the passage of the bilateral free trade agreement with the United States that was signed on October 24, 2000, and went into effect in 2002. The agreement included an obligation to adopt anticircumvention provisions of the sort mandated by the DMCA.31 Such provisions render illegal even forms of copying that might qualify as fair use by criminalizing the disabling of copy-protection mechanisms. Economic incentives were thus accompanied by the forced importation of stringent American copyright statutes.

The period immediately following the signing of the trade agreement saw a significant increase in the number of copyright infringement cases filed in Jordan: from 6 in 2000 to 149 in 2001 and 210 in 2002.32 Motion picture and software piracy remains rampant in the country despite efforts to conform to international standards of intellectual property law. Nonetheless, it is not unreasonable to expect that copyright legislation in the vein of that of the United States and the European Union will increasingly make its way to the country, resulting in augmented efforts to clamp down on piracy and in the impoverishment of the public domain. In Ramon Lobato’s words the exportation of American-style copyright legislation to other countries through provisions in free trade agreements provides “a taste of the IP maximalism to come.”33 During this moment of transition the recirculation of Struggle in Jerash asserts the value of a resource that might be lost—or, at the very least, rendered illegal to repurpose—if such developments were to occur.

Documentary in Fiction

The notion of a cultural commons is crucial not simply to the gesture of bringing Struggle in Jerash back into circulation but also to the remarks found on the commentary track and, indeed, to the original film itself. Three primary forms of discourse populate the commentary that runs through Simpson and White’s version of Struggle in Jerash: translation, historical contextualization, and the retrieval of documentary information about Jordanian history from within the film’s fictional diegesis, often in the form of comparisons to the present day. Some respondents narrate what is happening in the film, translating key fragments of dialogue into English, so that this new version of Struggle in Jerash remains intelligible to viewers who have not seen the 1957 film. Adnan Madanat speaks through a translator, supplying a wealth of information concerning the production of the film and the context of its release. He relates, for example, that the movie was banned on its release owing to the appearance of the lead actress in her bathing suit and the inclusion of a kissing scene at the film’s end. He adds that according to Mustafa Najjir the ban was overturned after Prince Hassan—at the time only ten years old—saw the film and “considered it a national achievement.” Madanat also narrates the rediscovery and subsequent loss of the surviving 35 mm print. His contributions come closest to the variety of critic’s voice-over that might be found on the special features of a DVD release of a historical film. His voice occupies a distinctly different discursive register from the others on the soundtrack, who seem to be encountering the film for the first time.

While the translation and historical contextualization serve clearly important functions within Struggle in Jerash, perhaps most interesting are the many remarks constituting the third form of commentary: observations that engage in a comparison and contrast of the Jordan depicted onscreen and the Jordan that exists today. As Bill Nichols has noted, every film is a documentary film; beneath the veneer of fiction, the moving image captures a real profilmic event, real landscapes, real monuments.34 In a country such as Jordan, where no official audiovisual archives exist and very few films were produced prior to 2007, the images of Struggle in Jerash possess a strong testimonial value, even when they are integrated into the fabric of fiction. The 1957 film is of interest not simply because of the key position it holds in Jordanian film history but also because of the historicity of its images. When watching characters swimming in the Dead Sea, commentators remark that the water level was higher then and that the water appears to be less salty than it is today; in an extreme long shot showing mountains on the horizon, one speaker says, “These mountains are now filled with refugee camps.”

Such voices guide the viewer to see forms of documentary testimony in Struggle in Jerash behind the fiction. Significantly, though, this investment in nonfiction representation exists also in the 1957 film. The film is riven between two tasks: constructing a narrative drawn from popular genres and using the moving image to showcase landscapes and important historical and religious sites within Jordan. The film begins as a romance, as the protagonist, Atif, picks up his love interest, Maria, at the Amman airport. Maria is Jordanian but left for Turkey when she was ten years old. Though her age is ambiguous, she would most likely have departed the country before its 1946 independence. Atif, an employee of the Department of Investigation, takes Maria on a series of dates that also serve as a tour of the country. The film takes a turn toward the gangster genre when a band of crooks target Atif during his and Maria’s outing to Roman ruins at Jerash, but after justice prevails, the romance resumes (figure 4.5).

FIGURE 4.5 Still from Struggle in Jerash (1957/2009). Courtesy of Eileen Simpson and Ben White, (cc) Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0.

Alongside this narrative intrigue lies another project, one very much bound up in the efficacy of cinema in nation building, of the power of a people representing itself to itself. Maria tells Atif, “As long as I am by you I feel like I am home.” He answers, “You are truly home,” to which she responds, “It’s true. I was born in Jordan.” This moment represents an intersection of the film’s two axes, as the romantic story line meets the film’s desire to use cinema as a way of creating a nationally shared image repertoire. An amorous remark is resignified as an assertion of nationality. As if to create a Jordanian national cinema ex nihilo, the filmmakers of Struggle in Jerash ensured that as much as they might appropriate the narrative conventions of the Egyptian films that dominated the region, their film would be specifically Jordanian. It would, in Benedict Anderson’s terms, imagine the nation-as-community through the cinema. As noted above, Struggle in Jerash appeared only eleven years after Jordanian independence and did so in a void of indigenous representations of the new nation-state. The precise territory of this new nation was also changing: Jordan captured the West Bank in the 1948 Arab-Israeli War and formally annexed the West Bank and East Jerusalem on April 24, 1950.

Easily identifiable locations in Jerusalem, such as the Temple Mount, feature prominently in the film. When Maria and Atif travel to the city on her second day in the country for a leisurely outing, the car journey from Amman is given ample screen time, beyond any narrative function it might serve. After Atif’s car pulls out of the driveway, there are forty seconds of extreme long shots of the car traveling across the Jordan River and through the landscape. No dialogue is heard; the interaction between Atif and Maria cedes its place to the display of territory. The film returns to the pair for a six-second medium long shot before departing again to display the landscapes of Jerusalem. Rosalind Galt has suggested that “landscape images in film are uniquely able to investigate [the] relationship of politics, representation, and history because landscape as a mode of spectacle provokes questions of national identity, the material space of the profilmic, and the historicity of the image.”35 Landscape provides a way to visually represent otherwise intangible notions of identity, to anchor a people to a place. Such deployments of landscape generally rely on on-location shooting, which injects a charge of actuality into what would otherwise be a fictional diegesis. Landscape emphatically emerges as a mode of spectacle in Struggle in Jerash, one carrying a strong political and affective charge for viewers in 1957 as much as today. Since Israel recaptured East Jerusalem and the West Bank during the 1967 Six Day War, visa issues and border checkpoints can make mobility between Amman and these areas difficult. After Maria and Atif cross the Jordan River, one female commentator remarks, “That’s crazy. That’s what my mom used to do. They used to go and have lunch in Jerusalem and then come back to Amman for dinner, all in one day. It used to take an hour. Now it takes a whole friggin’ day.” As the sound of the call for prayer rings out over a series of extreme long shots of the old city of Jerusalem, a male commentator remarks, “It’s still used now. In all Muslim countries around the world, in movies it’s always a symbol. To tell that you are in a Muslim country you put in the background the sound of the adhan, which is the call for prayer.” In this instance the pairing of sound and image serves to signify a claim over contested land.

After these long views over the city, Maria and Atif visit the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa Mosque, where in 1951 Mostafa Ashu, a Palestinian, assassinated Abdullah I, the first king of Jordan. On the commentary track one commentator notes that the film depicts the Jordanian crown at the door of the mosque—something that has long been absent. Though the film’s characters are ostensibly present during this sequence, they largely disappear. The film breaks out its already tenuous fiction and shifts into a mode of nonfiction address typical of the historical documentary or travel film, with a male voice-over supplying information about the various attractions depicted onscreen. Maria and Atif must form part of the crowd of tourists that one sees onscreen, but they are not easily identified. The cinematography clearly prioritizes the documentation of these landmarks over any advancement of the fictional narrative. When the characters do reappear, they do so almost incidentally. On the commentary track a woman notes that the film uses classical Arabic for the voice-over that is quite different from the colloquial speech of the rest of the film, emphasizing how clearly the film shifts its mode of address in this sequence.

After the End of History

In her 1999 book, Experimental Ethnography: The Work of Film in the Age of Video, Catherine Russell writes, “Often including apocalyptic scenarios of crisis and destruction, found-footage filmmaking tends toward an ‘end of history.’ The techniques of appropriation, recycling, and re-presentation place the status of the past, the history of the referent, in question.”36 Since the publication of that work, Russell has changed her attitude about the relationship between found footage and historical memory, stating that such practices can now provide “interesting access to cultural history” and that “film-makers are using images in ways that are not simply recovering the past but bringing all these histories to light.”37 Struggle in Jerash provides ample evidence to support Russell’s optimism that repurposed archival images might in fact offer creative ways of reopening cultural history. The project displays an understanding of a film not as a discrete, self-enclosed text but rather as a social space that can facilitate dialogue and memory. To use the terminology of Bruno Latour and Adam Lowe, Struggle in Jerash attempts to explore the “catchment area” of the work of art, that zone through which it travels via reproduction.38

The project also demonstrates an adamant refusal to find in its appropriated material a determinate point of origin. A work such as Sherrie Levine’s After Walker Evans (1980) engages in a critique of the author-as-origin, but its very subversion of this notion is a form of reliance on it. In Struggle in Jerash, by contrast, the point of interrogation is shifted from an attempt to reconfigure producer-consumer relations to focus instead on the mediating term of circulation. The result is that the status of the author ceases to be the main point of interrogation, as is so often the case in works trafficking in found materials. Instead, the travels of the image become paramount, particularly the reproduction of images across formats and beyond their sanctioned or intended uses. But against the utopia of free circulation, Simpson and White cannily signal that whatever “image commons” may be said to exist is at once a contested ground under increasing threat. They fulfill Joselit’s call for artworks to “build networks into their form by, for example, reframing, capturing, reiterating, and documenting existing content,” but they do so while troubling his primary assumption: that these networks are mere pathways through which images may circulate as they like rather than channels that variously mediate, block, shape, and condition that which moves through them.39

A key element of Steyerl’s concept of the poor image is the notion that the low-quality copy bears the imprint of its travels. One certainly sees this in Struggle in Jerash, not only in the degradation suffered by an image that has passed through multiple generations of copying but also on the soundtrack’s capturing of those who encounter the past in the present through their viewing of the film. Here one finds an inversion of the idea that it is solely the auratic original that is inscribed with time; the copy, too, is shown to possess the ability to register the traces of its passage through the years. Theodor Adorno was deeply critical of Benjamin’s notion of aura because he believed it risked resuscitating an ideal of authenticity precisely at the historical moment that such a thing became impossible to experience. As Adorno put it, “It is hardly an accident that Benjamin introduced the term [aura] at the same moment when, according to his own theory, what he understood by ‘aura’ became impossible to experience. As words that are sacred without sacred content, as frozen emanations, the terms of the jargon of authenticity are products of the disintegration of the aura.”40 Although Adorno articulated a scathing critique of authenticity, he also reserved a positive use of the word, one that locates the authentic in what is vulnerable and transient rather than pure and fixed. As Martin Jay has noted, this usage of the term tended to take the form of Authenticität rather than the Heideggerian neologism Eigenlichkeit. It thus left behind the existential notion of what was “ownmost” to the subject and instead designated “artworks that register the passing of time, the inability to return to something primal and originary.”41 In other words, for Adorno the possibility of true authenticity lies paradoxically in that which denies what is often taken as authentic, namely, an uncorrupted return to a purity of origins. As he writes, “Scars of damage and disruption are the modern’s seal of authenticity; by their means, art desperately negates the closed confines of the ever-same.”42 A modern conception of authenticity would not resurrect how things were then but rather register how that then has weathered the passage into this now. In all its scratches and blotches, video scan lines, compression artifacts, and polyvocal commentary, Struggle in Jerash registers “the scars of damage and disruption” that accumulate as time passes and thus opens the possibility of that paradoxical thing, an authentic copy that leaves the regime of private property far behind.