Have you ever noticed that nearly every form we fill out asks us to choose one, male or female? Everything else is presented as an open-ended question, or at least has more than two options. With such a diverse planet, and each human being unique, why must we force ourselves into two cramped boxes when it comes to sex and gender?1 My wish is that forms would ask us to write in our gender just as we write in our name. There are too many of us with too many identities to be suffocated by just two options.

Transsexualism, or transitioning from one sex to another, often with hormones and surgery, is only one type of transgenderism. Although it is often used synonymously with the term transgender, as we know, there are many more people than just transsexuals who fall under the umbrella of transgenderism.

We are going to start out with genderqueer because the term is growing in popularity to describe, for the most part, people who feel that they are in between male and female or are neither male nor female. Well, you might ask, what does that mean exactly? In the simplest terms, it means that, for example, a person who was labeled female at birth feels that he or she is not a woman but not exactly a man, either. This can be confusing for many, including the genderqueer person, especially in the beginning. However, this does not mean that this person is perpetually confused about gender identity. He or she may feel genderqueer permanently; in other words, it is not always a stepping stone to full transition. People can be perfectly clear that their gender is genderqueer, and that is how they live their lives. At the same time, the label of genderqueer is a common stopover for those who are not sure whether they are going to transition and are trying to figure out their true gender identity.

Is it difficult to be genderqueer out in the world? Absolutely. We’ve talked about pronouns, bathrooms, and other day-to-day issues earlier in this book. If you are genderqueer, those issues are constant, especially if you present as someone who is in between a typical man and a typical woman.

People often find the notion of genderqueerism difficult to understand. They may hear that a genderqueer person is in between male and female, or is neither, but they may continue to ask, “Okay, so what sex or gender does that make them, really?” This is where it is perhaps most difficult to live as a genderqueer person. The constant explanations that sometimes get nowhere can be frustrating and disheartening for genderqueer people. For instance, what pronoun does a genderqueer person use? Well, it depends on personal preference. Some will use “he” or “she” because they are easiest to use in public or because one fits better than the other. However, some genderqueer people use altogether different pronouns such as “ze” (instead of he or she) or a singular “they” (as in “they went to the store today” when referring to only one person). Some will make up their own pronoun that may be unique to them. Some will prefer to use only names and no pronouns, which can become awkward: “Jamie went to the store today. Jamie bought some grapes and oranges, then Jamie brought them out to Jamie’s car.” Well, you get the point. Using any alternative pronouns besides he or she requires a lot of time and effort in terms of explaining them. Sometimes people do not want to make gender the focus of their task, so if someone in a store refers to the genderqueer person as “he” or “she” and the person does not want to engage in a discussion of gender and pronouns, the person may let it slide. At the same time, it can be demoralizing, just as it is to “mispronoun” any person.

There are also many people who identify as genderqueer transmen or genderqueer transwomen. They may identify as men or women, but with a component of genderqueerness; they don’t fit into the binary of “just man” or “just woman.” Micah Domingo, a self-labeled genderqueer transman, describes himself:

From my vantage point, I can see the binary in a clear way. With this perspective, I have the honor of blending the binary and creating something completely new and different. To others, I am a mystery of gender, an in-betweener, a gender nomad. The fact that I love musicals is not a gendered act. Neither is playing video games, making sure I look pretty, reading Vanity Fair, being on stage rapping, tying my shoes, wearing a suit and tie, or dancing. I do have a masculine leaning, but I tend to stray away from anything that reinforces the gender binary. I know that none of those activities, or any activity, is only for one gender. I am capable of doing anything I want and still identifying as male.2

An important note: there are many people who fit the definition of a genderqueer person but do not call themselves genderqueer, either because they do not like the word or because they don’t feel it fits them. They may refer to themselves as gender variant, gender nonconforming, androgynous, a myriad of other terms, or they may use no terms at all. It is important to let people define themselves rather than be labeled by someone else.

GENDER VARIANT OR GENDER NONCONFORMING

The terms gender variant and gender nonconforming are similar, and the use of one or the other really comes down to personal preference. Any transgender person can be considered gender variant or gender nonconforming because he or she, by definition, does not conform to Western society’s notion of what a male or a female is. A person assigned male at birth who is very feminine and may like to dress in feminine clothes or participate in typically female activities, but who still identifies with his birth sex, might be gender variant or gender nonconforming. The term is usually used for people assigned male at birth because it is more obvious when a man engages in stereotypically feminine behavior than it is when a woman engages in stereotypically masculine behavior. This is because of our society’s lenience toward tomboyishness, especially in childhood, and rejection of most boys or men who enjoy feminine or female things. Gender variant or gender nonconforming can, however, be used to describe a female person who expresses herself as masculine yet still identifies as a woman.

Many gender-variant or gender-nonconforming people do not self-identify as such. These terms are often directed at natal male children who like “girly” or feminine behaviors, interests, or clothing. Although gender-variant and gender-nonconforming people fit under the umbrella term of transgenderism, we know that the term transgender is often used interchangeably with transsexual; therefore many of these gender-variant people are not labeled as transgender, per se.

Gender-nonconforming people are distinct from transpeople (transsexuals, that is) in that they may not feel as though their genitalia or secondary sex characteristics are foreign or as if they do not belong to their bodies. It is unknown why some people are gender variant or gender nonconforming but not transsexual,3 just as it is unknown what causes any aspect of transgenderism.

As we discussed in chapter 2, gender variance, especially with respect to gender expression, usually connects us with terms like gay or lesbian. Many gay, lesbian, and bisexual people are what you might consider gender variant. No matter what one’s sexual orientation is, life can be extremely difficult for those who live in the middle ground on gender. As the author of an article on transgender youth writes: “While there is space for such identities in some cultures, mainstream American culture is not one of them.”4

CROSS-DRESSERS

Cross-dressers are often confused with transsexuals as well as with drag queens or drag kings. There are several things that differentiate these terms. In short, cross-dressers are people who dress in clothing typically reserved for the “opposite” sex, either in the privacy of their own home, in places with other cross-dressers, or out in public. Cross-dressing is still widely known as transvestism, which is now considered a pejorative term. A person who cross-dresses should not be known as a transvestite, but as a cross-dresser.

When we think of cross-dressers, what images do we conjure up? A man in a dress? A man in women’s underwear or pantyhose? How about a woman in a jacket and tie? The latter image is probably far less commonly thought of, but that person can also be called a cross-dresser.

Statistics on cross-dressers are hard to come by. Most people do it privately and thus are not inclined to take a survey or tell people about it. Many cross-dressers have partners or spouses who are not aware of their cross-dressing, at least in the beginning. Sometimes a partner or spouse will find an article of clothing that does not belong to him or her but seemingly does not belong to the spouse either, and this can bring up a myriad of issues. Often the first thought is that the cross-dressing partner is actually having an affair. For instance, if a cross-dressing man is married and his wife finds a pair of women’s panties that don’t belong to her, she may jump to the conclusion that he is having an affair. Many spouses end up eventually finding out about the cross-dressing whether on purpose or by accident, and it can put a strain on the marriage or partnership. Some spouses will wonder whether the cross-dresser will eventually transition to the opposite sex, or whether this is a phase, or even whether it is a mental illness.

There is a diagnosis in the DSM-IV-TR called transvestic fetishism, also knows as autogynephilia. It is essentially when a man cross-dresses for sexual pleasure. However, many people cross-dress because it makes them feel more genuine, and they do not get sexual pleasure from it, nor do they intend to transition to the opposite sex. There is a great deal of shame involved in cross-dressing. It is ingrained in us as small children that cross-dressing is wrong. Even a young boy who consistently puts on his mother’s pantyhose and makeup knows that he should never tell her about it.5

Due to the shame associated with cross-dressing, many people sometimes purge their wardrobe of all the clothes and accoutrements associated with their cross-dressing. In other words, a man who cross-dresses may take all female-associated items out of his wardrobe and throw them away, hoping that this will stop his urge to dress in women’s clothes. It is possible that cross-dressing can be a phase, but for many people, it is something that they do long term. Therefore, many of those who purge their wardrobes end up replacing what they have thrown out, starting the cycle over again. Other reasons for purging might include fear of someone finding out about the cross-dressing, fear that a gender transition is inevitable, or fear that the person’s relationships will be damaged if it continues.

Many relationships do survive cross-dressing. Helen Boyd, author of My Husband Betty and wife of a male cross-dresser, writes about her thoughts on the subject:

Crossdressing is not necessary to a person’s survival, but it does seem to be necessary to his well being. Crossdressing is not, as some wives of crossdressers might wish, a selfish whim. Crossdressers as a group do not give it up despite the troubles it can cause in their lives. The phenomenon is stubbornly inexplicable, a cross between a compulsion and a wish.6

Each relationship handles cross-dressing differently. The following is part of the story of another woman who is married to a male cross-dresser:

I found out about my partner’s gender issues a little over five years ago right after our fourteenth wedding anniversary. We come from healthy, well-functioning, wonderful, church-going, middle/upper-middle class families…. I had virtually no clues about his “feminine side.” … I resented the times Joe had been away on business with his [feminine] clothes. It was like he had a fantasy woman I couldn’t compete with.7

This woman questioned whether it was worth it to stay in her marriage, but she ultimately decided to. She placed restrictions on her husband’s dressing that he agreed to because it meant that his wife would stay with him. Many spouses of cross-dressers never come to fully understand their partner’s inclinations nor do they accept the cross-dressing unconditionally. As with any issues that arise in relationships, each couple decides the best course of action to take. Another wife of a male cross-dresser, whose husband came out as such on their first date, said the following: “When we go out together, if there is something that he is wearing or doing that is obviously feminine I will point it out if it makes me uncomfortable. On the other hand, I will try and make him prettier when he wants to dress around the house.”8

Virginia Erhardt, author of Head over Heels: Wives Who Stay with Cross-Dressers and Transsexuals, the source of the previous two stories, believes that women who know about their male partners’ cross-dressing from the beginning have a better shot at staying in the relationship.9

Just as there are cross-dressers who do or do not derive sexual pleasure from the act of dressing in clothes associated with the opposite sex, there are also cross-dressers who are not shamed by the idea of dressing. They do not feel dysphoria about their bodies or their identities, and they see cross-dressing as a part of their lives just like any other hobby that is intertwined with their identity. Some cross-dressers take on a different name when they dress. Many will adjust their mannerisms, including voice, to fit the gender expression that they take on. For men who cross-dress, wigs, shaving legs and underarms, breast stuffing, jewelry, and makeup (among other accessories) are part of the experience.

So, what is the relationship between cross-dressers and transpeople (namely, transsexual people)? Well, although it may seem that cross-dressing is a step toward gender transition, the two groups remain distinctly different. It certainly can be a step toward transition, but in many cases cross-dressing exists on its own. In fact, there is a divide between many transwomen and male cross-dressers specifically; some transwomen believe that cross-dressers are too afraid to transition while some cross-dressers think that transwomen are merely cross-dressers who have gone too far. This tension is not unlike the divide between some butch lesbians and some FTMs. But regardless of these hostilities, the fact remains that transwomen who live full time as women are not the same as men who cross-dress occasionally. Transwomen are women, plain and simple. Explains one male cross-dresser: “I have no illusions about who I really am. I know that I am a guy, but sometimes it just feels nice being a girl for a while. It has been a part of me all my life, and I suspect it always will be.”10

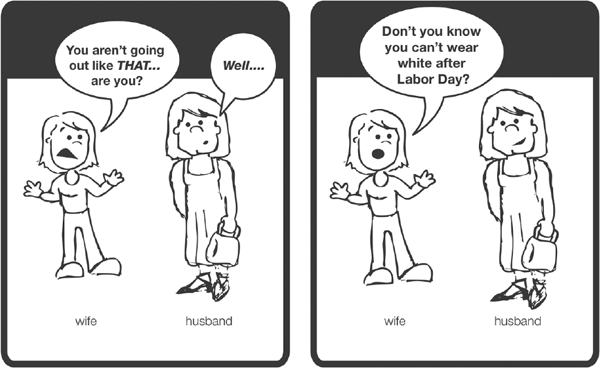

Figure 8.1

DISORDERS OF SEX DEVELOPMENT AND INTERSEX

People with disorders of sex development (DSD), sometimes called intersex, include those who used to be referred to as hermaphrodites. The term hermaphrodite, derived from the Greek mythological child Hermaphroditus, is now considered pejorative and should no longer be used. Hermaphroditus was the offspring of Hermes and Aphrodite and was “portrayed in Greco-Roman art as a female figure with male genitals.”11 “True hermaphroditism” was, until recently, a term used to describe a condition in which a person has both testicular and ovarian tissue.12

According to the Intersex Society of North America (now the Accord Alliance), intersex “is a general term used for a variety of conditions in which a person is born with a reproductive or sexual anatomy that doesn’t seem to fit the typical definitions of female or male.”13 But even the Intersex Society of North America officially moved to using the term disorders of sex development to encompass all intersex conditions. Just as in other areas of transgenderism, certain people have a preference for some terms over others. If someone prefers the term intersex over DSD then it is important to respect that.

For the purpose of simplicity in this chapter, I mostly use the term DSD. According to Children’s Hospital Boston, people with DSD have “medical conditions where average sexual development does not occur. DSD can include … medical issues that may make it difficult to determine a child’s sex or conditions that interfere with a patient’s sexual and reproductive function.”14 Another definition of DSD is that such disorders are “congenital conditions in which development of chromosomal, gonadal, or anatomic sex is atypical.”15 Though one might think it is rare that a child is born with such a condition, it is estimated that 1 in every 1,500 births is a baby with DSD.16 In fact, in the animal kingdom, excluding insects, one-third of all animal species are what we might consider intersex.17 Again, this shows how varied animals are. Human bodies vary too, which makes perfect sense, but social stigma prevents these variations from being normalized in our society.

Causes of DSD are not always known, but may include mutations of chromosomes or genes, or over- or underexposure to certain hormones while the fetus is developing in the uterus.18 Treatment of DSD depends on the specific condition and is always changing with new research. For infants born with ambiguous genitalia, the protocol used to be to do immediate surgery to make the child’s anatomy look typically male or female, depending on several factors. Nowadays doctors often try to persuade parents to hold off on surgery and to assign the child a gender identity based on an experienced medical team’s best conjecture. Parents should keep an open dialogue with their child as he or she grows older, and if the wrong gender was assigned or the child wants genital surgery, a decision can be made at that point. When a child with ambiguous genitalia is born, it is rarely a medical emergency. Unnecessary surgery on infants can result in a lifelong loss of genital sensation as well as fertility problems. Obviously, this can severely negatively affect a person’s life.

Many DSD advocacy groups currently recommend deferring surgery until a person can make his or her own informed decision (especially in the case of ambiguous genitalia) and letting the person with DSD and his or her parents have complete access to medical records.19 It may seem silly to even mention the latter recommendation, but many people with DSD have grown up with the facts shielded from them, whether by medical professionals or their own caregivers. It is the duty of parents or caregivers to be forthright with a child who has DSD.

It is important to know that although historically intersex/DSD has fallen under the transgender umbrella, many people believe that it should not be included. There can be transpeople (transsexual or otherwise) who are born with DSD and the two identities remain distinct. Some people are not aware that they have DSD, nor are their parents or doctors. It could be a chromosomal abnormality that has no outward effects. In this case, those who transition away from the sex they were assigned at birth might first and foremost identify as trans and then later may come to find out that they actually have DSD. This does not necessarily change their trans status. People choose their own language according to what feels right. As we know, some transpeople with or without DSD consider themselves just men or women and do not feel the need to acknowledge the fact that they passed through some atypical steps to become who they truly feel they are. On the flip side, many people with DSD do not consider themselves trans and may not wish to be associated with the GLBT community. They may view their DSD as a medical disorder only.

Many of those who are born with DSD are labeled, at birth, with the sex that corresponds to their gender identity. In other words, they are non-trans like the majority of the population, and may be able to lead a very typical life. For many, DSD is a private medical issue that need not be discussed at all. Others find solace in support groups. It may depend on the severity of the DSD. For example, someone with ambiguous genitalia who was forced into surgery as an infant likely has different emotional needs and concerns than someone whose DSD never affected his or her appearance and was successfully treated with hormone replacement therapy. Likewise, a person born with DSD may have been labeled as one sex but always felt like another, so he or she might undergo a gender transition much like a transperson without DSD. That person may consider themselves trans as well as having DSD/being intersex.

You might wonder how a person who is not 100 percent male or female in the typical sense could transition from male to female or vice versa. The fact is that virtually all babies born with DSD, no matter how severe, are given a gender identity via the physicians’ and parents’ best guess, so that he or she may grow up “normally.” These kids can be boys or girls just like everyone else. Some of these people may grow up and realize that they have a gender identity that doesn’t match up with the sex they were assigned at birth. Since they have lived as one sex and everyone knows them as such, they may undergo a gender transition like any other transperson.

Raven Kaldera, a self-described trans/intersexual FTM, was labeled female at birth but identified as a boy and ultimately transitioned to become one, though he was actually born intersex. Kaldera described part of his experience in a book that has the subtitle Voices from Beyond the Sexual Binary:

I feel like that much of the time, one foot in each world, frantically juggling opposite elements. Not just male and female either; there are also the separate countries of hormones and culture, intersex and transgender, spirituality and intellectualism, queer and transsexual, and so forth. The lines aren’t stable; they move around, but they’re easy to find. Just come and look for me. Where I stand, there’s the line. Where I move, the line goes with me. I live on it. It is imprinted into my flesh. You can take my clothes off and see for yourself.20

Drag queens and kings are always associated with performance. If you ever get confused between cross-dressers and people who do drag, remember that drag is for a performance. Legend has it that drag was originally an acronym for “DRessed As a Girl,” which was used in theater stage directions when women were not allowed to be actors (so men always played female roles). Of course, this was solely in reference to drag queens, before the advent of drag kings.

Drag queens are men who dress as women and perform as women. Though drag has historically been most popular in gay circles, one need not be gay to do drag. Similarly, drag kings are women who dress as men and perform. Most drag queens sing, lip-synch, dance, or do skits of some kind. Many drag queens impersonate female pop stars and vice versa for drag kings. People who do drag on a regular basis often have a drag name (a name for the woman or man that they become) and sometimes a drag personality.

There are drag troupes that travel around or do shows on a regular basis at a nightclub or other establishment and have large followings. All the Kings Men, a group of traveling drag kings based in Boston, bills itself as an “all female, character-based performance troupe that creates wholly electrifying cabaret-style and modern vaudevillian productions … [made up of drag kings] who collectively play between thirty and fifty gender bending characters per performance.”21 There are annual national and regional pageants for both drag queens and drag kings.

Daniel Harris, author of Diary of a Drag Queen, begins his story with the following: “I have never wanted to be a woman, and I do not want to be one even now that I am trying to be one…. I have never had any doubts about my manhood, never been plagued by gender confusion, never felt like a ‘woman trapped in a man’s body.’”22 Harris illustrates the clear distinction between being a drag queen as a performer and being a transsexual woman. This is not to say that there are not some drag performers who have a different take on their own gender. Some might use it as a stepping stone to transition, but some know that they just like to do it for show and will never live full time as the gender in which they do drag. Others might feel like they fall somewhere in between those two.

As a young boy, Chris Hagberg used to dress as a woman for Halloween. As he got older and came out as a gay man, he dabbled a bit in drag both on the stage and off. When he became involved in a gay men’s softball league, he acquired the drag nickname “Momma Kitty,” partially due to his maternal nature. To Chris, Momma Kitty and he are different in some ways but the same in many ways. He often dresses in full drag and becomes Momma Kitty for softball league events, including fund-raisers. There is one thing that Chris always notices: “Momma Kitty is her own entity, but it’s really interesting to see how people interact with me when I’m not in drag as opposed to when I’m in drag. People approach me differently when I’m Momma Kitty—there’s absolutely no two ways about that.”23 Chris mainly does drag for fun, but he contends that it is an interesting experiment in gender’s impact on approachability. Apparently, everyone is more talkative with Momma Kitty than they are with Chris. They will stop Momma Kitty on the street or at an event and start a conversation with her; they will confide in her with an almost automatic trust. When Chris changes back into his regular clothes and walks by the same people, they usually don’t recognize him. When he asks, “What, do I have to wear a dress to get you to talk to me?” they realize that it’s the same person they see before them, but they are still not willing to open up like they did when he was dressed as Momma Kitty. Chris believes that the Momma Kitty persona has helped him understand gender in a way that he never did before. His advice: “I think everyone should do drag once.”24

Now that you have learned a bit about other types of transgenderism that fall under the trans umbrella, hopefully you are armed with more knowledge than you had coming in. But before you go, I have a few final thoughts.

PARTING WORDS

In America, we have seen that teenage suicide because of bullying has reached epidemic proportions. Many of these kids are GLBT, and most of them are taunted due to some component of their gender expression. I hope that you will talk to others about what you have learned about transgenderism. No one should have to suffer because of who he or she is, but we know that reality tells us differently. People have been bullied and persecuted for who they are since the dawn of time. But we are not defenseless. The more education that is out there about what it means to be different, the better.

Maybe the next time you run across a form that asks if you are male or female, you will think about the absurdity of this question. If we consider the continua of gender identity and gender expression, there is really an infinite number of ways to be. Not everyone puts themselves in categories that have been described in this book. People can fall into all categories, some categories, one category, or no categories at all. What is important is realizing that human beings are incredibly complex creatures and gender is just one part of what makes us each unique.