Visitors’ Reactions

The Family of Man was shown in Munich from 19 November to 18 December in 1955. The exhibition’s first stop in Europe had been Berlin (17 September–9 October), where it had been an American contribution to the city’s fifth cultural festival, and where it had also proved to be an ‘unheard-of success’: the Hochschule für bildende Künste (Academy for Creative Arts), where the exhibition was shown in Berlin, counted an art exhibition to be a success if it drew 5,000 visitors over a three-week period; The Family of Man brought in over 12,000 in its first eight days and a total of 42,000 by the end of its three-week run. And the exhibition enjoyed a similar success in Bavaria during its four-week run at Munich’s Städtische Lenbach-Galerie (Municipal Gallery), co-sponsored by Amerika Haus, where it was seen by 32,500 visitors, roughly a thousand per day.1 The same team was responsible for hanging the exhibition in both Berlin and Munich, but the Munich installation appears to have been more successful. According to Dorothea von Stetten, Manager in the Exhibition Section of the American Embassy, the exhibition in Munich was ‘more dramatic and more accentuated, and much better lit’, an impression that is borne out by the available installation photographs from the two venues.2 The Family of Man returned to Germany in 1958 and was seen in Frankfurt, Hamburg and Hanover. When the attendance figures for 1955 and 1958 from all five cities are combined, the number of German visitors to the exhibition comes to a total of 161,000.3

The international tour of The Family of Man was sponsored by the United States Information Agency (USIA, known abroad as the United States Information Service or USIS). The USIS in Germany promoted Steichen’s show with a great deal of energy, and this effort undoubtedly contributed significantly to the immense popularity of the exhibition. In Munich, a press preview was held for 45 representatives of newspapers, magazines, radio and television from the city and other parts of Bavaria. This resulted in at least 101 articles and picture stories in 95 separate publications, with a total circulation of 5,680,000. Local radio and television provided almost 90 minutes of airtime and access to three million viewers and listeners.4 Previously in Berlin similar previews for the media had been arranged, and in addition the USIS distributed several hundred copies of the book of the exhibition and organized ‘extensive poster advertising’.5 The enthusiastic endorsement of the respected critic Friedrich Luft seems to have been especially influential in Berlin. An actor, journalist and screenwriter, Luft was also ‘a very influential Berlin cultural commentator’. He ‘devoted one of his regular and widely listened-to broadcasts, usually reserved for film and theatre reviews, to a strongly favorable description of the exhibit, urging his listeners to go and see it’. According to the USIS report, ‘for many Berliners this was the authoritative stamp of approval’.6

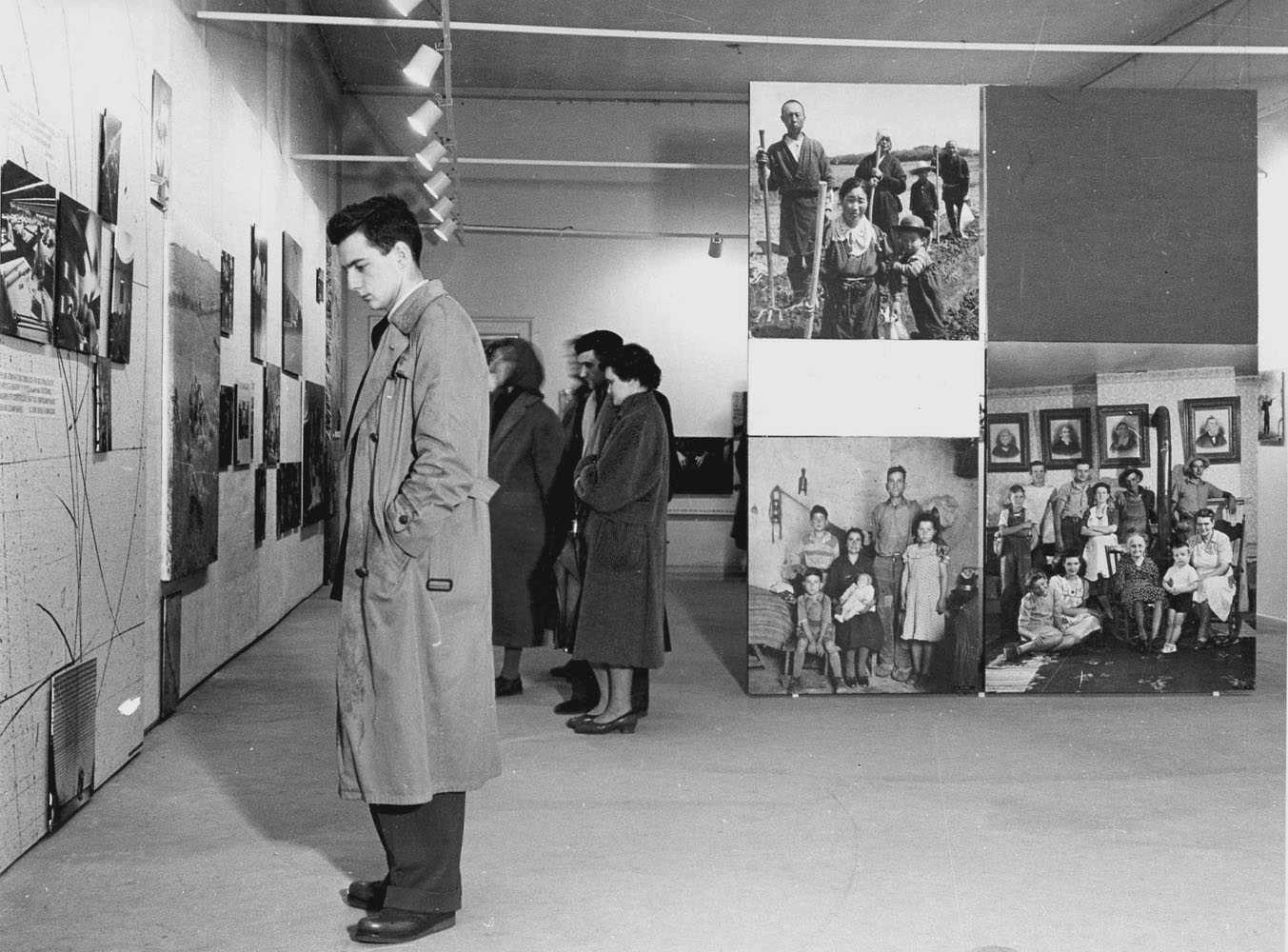

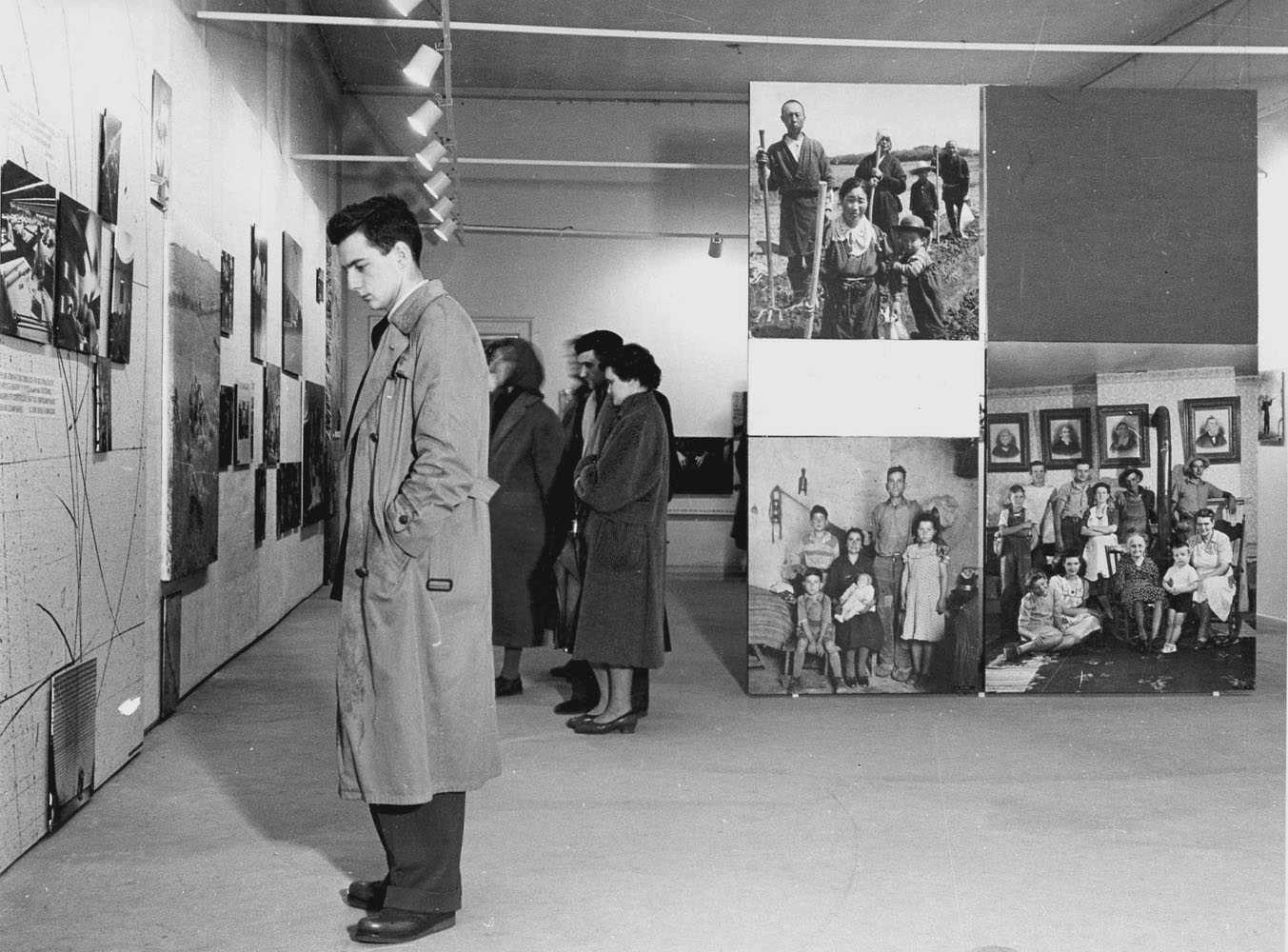

14 The Family of Man at the Städtische Lenbach-Galerie, Munich, Germany, 19 November–18 December 1955.

But neither the imprimatur of a cultural authority such as Luft, nor the efforts of the USIS, can fully explain the scale and enthusiasm of the public’s response to Steichen’s show. The USIS after all made similar efforts to promote other exhibitions it sponsored but without results to match – not in Germany, and not anywhere else in the world. We cannot properly account for the phenomenon that The Family of Man became without acknowledging the role that the public itself played in its promotion. As the USIS itself noted, ‘the most successful instrument in promoting’ attendance in the early stages of the exhibit in Berlin proved to be a ‘sneak preview’ organized for ‘the day before the exhibit’s official opening’. ‘Personal letters were sent to some 500 photo dealers and camera club members’ inviting them to a preview in the morning, and another 400 invitations were sent to another selected list for an afternoon preview the same day. Some 450 people came.7 What is important about these sneak previews is that their success in bringing visitors to the exhibit was dependent not on further advertising and USIS-dictated publicity but on word of mouth, and on communicating a personal experience of Steichen’s show.

The staggering number of people who went to see The Family of Man around the world is without question the most compelling fact about the exhibition, and yet this is also the aspect of the show that has received little or no critical attention. Although the attendance figures confirm a near uniform level of interest and appreciation across dozens of countries, we know nothing in detail of what visitors thought or felt, what in particular held their attention or did not, and why. This is hardly surprising since direct testimony about such matters appears not to have been collected while the exhibition was on tour, and is now, given the passing of the years, impossible to come by. Munich, however, provides us with a notable exception to this lacuna in our understanding of The Family of Man.

While The Family of Man (or Wir Alle – All of Us – as it was called in Germany) was in Munich, a city that had been under US occupation from 1945 to 1948, the research staff at the American Embassy’s Office of Public Affairs commissioned DIVO, Gesellschaft für Markt- und Meinungsforschung m.b.h. from Frankfurt-Main, a respected German opinion survey organization, to prepare a report on visitors’ reactions to the exhibit. This was one of a number of reports similarly commissioned in the decades following World War II to survey German responses to various exhibitions and cultural events organized by the US government authorities, as well as perceptions of American culture, society and politics.8 A primary reason for why the American Embassy took such care to canvass public opinion in West Germany must have been because of the country’s geopolitical importance in the Cold War in the aftermath of the war; it was a new ally for the US and an especially important partner in the struggle against the Soviet Union. No doubt this is why Berlin, the divided city at the very centre of Cold War confrontations, was picked as the first European venue for The Family of Man. It would be another six years before the wall dividing the east of the city from its western part would be built; this meant that at least a quarter, and perhaps as many as a third of the 42,000 visitors who came to see the show in Berlin (including Bertolt Brecht and a young Gerhard Richter) actually came from East Germany.9

We don’t know what visitors from the ‘Eastern Zone’ made of Steichen’s exhibition, but the survey from Munich does provide us with a remarkably detailed and wide-ranging summary of West German public opinion.10 The survey is one of only two documents relating to The Family of Man that I am aware of that provide us with access to what several hundred visitors from a particular city and country, out of the final total of more than nine million from 48 countries, thought and felt about the exhibition (the other document, also an audience survey, is from Mexico City).11 Inevitably, the recorded responses were mediated by the survey format and by at least some of the cultural and political imperatives that were behind the survey’s commissioning. But it remains the case that these documents nevertheless provide us with a rare glimpse of some of the thoughts and feelings of The Family of Man’s international audience, a glimpse that is far more direct and more grounded in specifics than the broad celebrations in the media, or the undeniably forceful but also blunt facts of global attendance figures. This is especially true of the Munich report that is both methodologically more rigorous and self-aware than the Mexico City survey, and far more detailed and extensive in charting a wide variety of responses. The Munich survey, like the Mexico City one, has not previously been examined in the critical literature on The Family of Man; it is because of this, and because it makes a particularly invaluable contribution to the European dimensions of the present volume, that its findings are summarized here.

The Munich survey was based on interviews with 770 visitors conducted over the four weeks that the exhibition was in the city. A total of 298 of the visitors were interviewed as they left the exhibit, and 472 were interviewed at their homes by appointment, two or three days after their visit to the show: ‘The purpose of this procedure was to locate possible differences between the immediate feelings and reactions of the audience and those judgments and views reported after some lapse of time during which discussions and exchange of impressions had most likely taken place’ (i). The questionnaires used for the two sample groups were similar, though ‘a greater number of questions, resulting from more detailed queries, were asked in the home interviews’ (i). The findings of the survey were compiled along with comments and analysis by the research staff of the Office of Public Affairs at the American Embassy in a detailed and careful report, 87 pages in length, titled ‘Visitors’ Reactions to the “Family of Man” Exhibit’, dated 23 January 1956. Though those interviewed at home would all have been Muenchners, at least some of those surveyed at the exhibition itself must have been from other parts of Bavaria: ‘groups of university students, art students, factory workers, photo-clubs and other club groups came by bus, train and private car’ to the show (without direct solicitation in fact) ‘from all over South Germany’.12

The primary purpose of the survey for the United States Information Service (USIS) was to determine ‘whether – and to what extent – the exhibit contributes to USIS objectives […] in Germany’. Two questions were central to these determinations: ‘1) Do exhibit visitors recognize the theme of the show or is it simply considered an arty photographic exhibit and 2) Do visitors as a result of the exhibit credit the U.S. with sincere efforts to achieve peace and understanding among peoples of the world?’ (i). The USIS research staff who compiled and analysed the findings of the survey were themselves quick to acknowledge that the survey only answered ‘questions which arose among USIS policy officials in West Germany in considering the impact and effectiveness of [the] Steichen show in the light of USIS objectives’. This proves to be too limited a description; the survey in fact allows us to see much more than USIS preoccupations at work, whatever the original motivations behind its commissioning. But the authors of the report were especially perceptive when they noted a different limitation, one that all commentators on The Family of Man must acknowledge if they engage with the question of audience response and experience. ‘In studying the effect of the show,’ the report commented, ‘we can only consider reactions which are verbal, hence surface expressions.’ A proper understanding of the exhibit requires us to go below this verbal surface because ‘a considerable part of the influence of the Steichen show is of such a subtle nature that the results are difficult to locate even with far-reaching probing techniques since these influences awaken purely emotional reactions’ (6).

The exhibition had of course been devised by Steichen independently of the USIA and its programmatic objectives (which is not to say that consideration of cultural politics played no part at all in its early planning): the report itself reiterated at its very start Steichen’s insistence that The Family of Man had been created ‘with no propaganda intention of any kind whatsoever’ (i). It is nevertheless the case that the international tour of the exhibition was very much under the USIS’s control, with the organization in charge of all the publicity and having at least some control over adding and removing pictures to suit local contexts and sensitivities. The USIS had adopted the exhibition because its theme or message fitted well with the American government’s international objectives. These objectives are articulated later in the report as explaining ‘America and its ideals to the German public’ and thereby creating ‘more favorable attitudes towards the United States’ (40). Steichen’s humanist commitment to a sense of global collectivity was of course not as narrow as this, but it was telling that, while ‘about half of the visitors had no opinion as to which country in the world does most to realize the ideals expressed in the exhibit’, 40% of visitors named the United States and only 8% named European countries (with only 3% choosing Germany itself) (61). The authors of the report noted with understandable satisfaction that the 40% ‘represents a very high score in a free answer situation’ (62), and that almost three-quarters of both the exit and home interviewees ‘received the impression through the exhibition that the United States is seriously trying to bring about understanding between the nations and races throughout the world’ (66).

These figures are perhaps even more impressive when we consider that only just over 60% of the visitors appear to have been aware that the exhibition was US-sponsored (with 30% indicating ‘America’ or ‘Americans’ as the sponsors, another 30% naming MoMA, and 1% saying Amerika Haus, the co-sponsor, along with the Municipal Gallery, of the show in Munich) (62). The figure of 61% was clearly seen as too low by the USIS head office in Washington, and was raised as a matter of concern with the American Embassy staff in Germany. Milton Leavitt, Assistant Public Affairs Officer in Munich, and the person primarily responsible for the organization of the exhibition there, responded by saying that he had ‘visited the exhibition each day’ and that he was sure that in fact the percentage of people recognizing US sponsorship was higher. But Leavitt also argued astutely that it was ‘more important to the [USIS] program to present a tremendously effective exhibit […] than to present exhibits on which there is no doubt of their sponsorship but have them prove ineffectual (which has happened so often in the past)’.13

Leavitt had spent time with Steichen discussing the exhibition and listening to his lecture on photography and The Family of Man, when Steichen had first visited Munich in September 1955 (while the exhibition was still in Berlin). He also delivered a lengthy speech outlining the major themes of the exhibition and the process by which the show had been put together by Steichen and his team at the Munich opening, and he may well have had a hand in the report on visitors’ reactions in Munich.14 Leavitt’s comments on the effectiveness of the exhibition, and his implication that communicating the core philosophical message of the show was more important than ensuring awareness of its American sponsorship, would have been welcomed by Steichen for whom the USIS was first and foremost a vehicle for making The Family of Man accessible worldwide, and not a body in charge of the show’s meanings. Steichen, who was certainly aware of the Munich report, must have been equally pleased that the survey focused above all on the broad scope as well as the particular iterations of this message, and on the ways in which these were understood by the visitors.

The report summarizes the findings of the survey as follows, and given the substantial evidence provided in support of it, the summary is accurate and credible:

The ‘Family of Man’ exhibition in Munich attracted an audience of exceptionally high intellectual level and received an outstandingly favorable reception from almost all of its visitors. The ratings are the highest ever found for any exhibit including the 1954 ‘Atoms for Peace’ exhibit in Berlin. There was frequent usage of such extremely favorable terms as ‘superior’, ‘excellent’, ‘outstanding’, ‘without precedent’ and ‘magnificent’ – terms which are rarely found in audience reactions studies. The emotionally-stirring and deeply moving effect of the Steichen show resulted in strong enthusiasm which was especially apparent in the exit interviews conducted immediately after the show.

Although the differences between the two samples are only small, and, strictly speaking, statistically insignificant, two general tendencies are apparent. First, after a short time lapse, enthusiasm is slightly less and somewhat replaced by an appraisal which is still far above the ordinary. Second, clear understanding of the underlying idea increases with the passage of time.

The ideals of the exhibit are clearly perceived. Its purposes and effects are described as stimulating thinking concerning the problems of the human community, and inspiring humanitarian feelings by presenting the unifying elements common to man and thus promoting friendship and peace among all nations and races. Therefore, one is justified in concluding that the pictorial approach of presenting the theme was highly successful. (1)

Perhaps the most important detail to note here is the ‘exceptionally high intellectual level’ of the audience: the measure here was not only in relation to the educational level of the public at large (one would expect visitors to a photographic exhibit at an art gallery to have above-average educational attainment); it was rather in comparison to the make-up of audiences for other exhibitions previously sponsored and organized by the USIS. According to the report, 84% of ‘the rank and file people in West Germany have elementary schooling only’. By contrast, 89% of the visitors to the exhibition in Munich were found to have gone beyond elementary school: ‘In fact about twenty times as many persons with university training’ were found in the audience ‘as are to be found in the general population’. And the unusually high proportion of educated visitors was matched by ‘a much greater proportion of men’ than the USIS would have anticipated for one of its cultural or art shows.15 It is not surprising then that there was also a disproportionately high representation of ‘the prestige occupations and higher income groups’: what the report refers to as ‘upper middle class’ and ‘upper class’ individuals made up 30% of the general population in Germany in 1955 but 84% of the audience surveyed; according to the survey, about 2% of the population had been to university, but the figure was 41% among the Munich visitors to the exhibit (1–2). These figures and breakdowns are important because they reveal an exceptionally high presence of the ‘opinion-leading elements’ (1). The report is right to conclude then that, ‘considering the exceptionally high educational level of this particular audience, the findings […] become even more important and gain in significance since members of the elite groups are usually found to be much more critical than other groups in the population’ (6). One could add, in regard to the relatively high opinion of the United States expressed in the survey, that this educated and professional segment of the population is precisely the group one would expect to be most likely to be critical of American cultural propaganda and foreign policy.

Equally noteworthy is the near unanimity of opinion expressed between the ‘less educated’ (which was taken to mean those with an elementary school or secondary school education without Abitur (diploma)) and the ‘more educated’ (meaning university educated as well as those with the Abitur which was a necessary degree for studies at university): 52% of the former said they liked the exhibit ‘extremely well’, and 39% said they liked it ‘very well’; the figures among the ‘more educated’ were 50% and 35% respectively (10).16 In other words, right across the West German social and educational spectrum, from those with little more than an elementary education to university graduates, white collar professionals, and intellectuals such as Max Horkheimer, Wolfgang Koeppen and Siegfried Kracauer (as well as all newspapers and magazines), there is a near complete consensus about The Family of Man, and a remarkably positive assessment of its cultural achievement that stands apart from the many ideological critiques of the exhibition that were contemporary to it or have appeared regularly since the 1950s, and from accounts that have dismissed the exhibition as nothing more than American Cold War propaganda indistinguishable from the programmatic aims of the USIS. Only 2% of those interviewed saw the objectives of the exhibition as making ‘propaganda for the United States’ (1%), or ‘to propagandize democracy’ (1%) (41).

As the summary of the survey quoted above suggests, most visitors grasped the ‘theme’ or ‘message’ of the exhibition in more or less the terms in which Steichen had intended. And they responded with almost equal enthusiasm to Steichen’s unusual presentation of the photographs. Roughly a quarter of the visitors who came to the Munich show had been to one or more photography exhibitions during the previous year, but the majority of them rated The Family of Man far more highly than any other photography show they had seen: 90% of the interviewees commented favourably on the ‘composition and arrangement of the pictures’ and on their ‘shape and size’ as aspects of the exhibition that had appealed to them (18), although the majority of those who did comment favourably on the aesthetics of the show did so while noting that Steichen’s use of photography was only a vehicle for the message he wanted to convey (46–8). And almost every visitor who was interviewed said that they would recommend the exhibition to others, and agreed that the exhibition should be shown in other German cities (50). A significant number of the visitors (some 40%) pointed to the quality of the display and the revelation of the communicative potential of photography as one reason for making such a recommendation (16), but the overwhelming majority gave as a reason the importance of the underlying ideas of the exhibition, and emphasized ‘its stimulating effect on thinking about problems of human life, promoting international understanding, inspiring humanitarian feelings, and explaining what is common to all men’ (14). As one visitor put it, he or she would encourage others to come to the show ‘because my relatives and friends would be led to see – as it happened to me – how absurd it is to believe that people of other races and nationalities, of another faith, or living under another governmental system would feel any differently from the way we feel’ (15).

Only about a third of the visitors said that they had gained new insights or learned something new after visiting the exhibition. But this was hardly surprising given the educational level of the audience. Many would have ‘very probably spent a considerable amount of their spiritual and intellectual life being concerned with the problems and philosophies expressed by the show’, and would have already subscribed to Steichen’s humanist message. ‘Thus with most visitors the impact’ of The Family of Man did not reside ‘in the transmission of new ideas, but in the reactivation of old ones’ (57). Given the prevalence of this shared belief in the common bonds that tie human beings together across cultures and times, the authors of the report were right to note that it was a ‘tribute’ to the achievement of The Family of Man ‘that over two-thirds (68%) of those who basically felt that men are too different [which was 15% of those interviewed, 67] were impressed by the photos because they demonstrate the exact opposite (i.e. that races and nations fundamentally have more in common)’ (56).

Broad assessments of the form and content of The Family of Man such as these are extremely valuable for anyone wanting to understand what ‘ordinary people’ or the ‘general public’ (as opposed to critics and academics) might have made of the exhibition in the 1950s, but perhaps the Munich survey contributes to this understanding even more by allowing us to drill down to more specific reactions and responses. In addition to assessments of the overall design and thematics of the exhibition, the survey maps audiences’ responses to particular groups of photographs as well as to individual photographs, with many direct comments from visitors included as in all other sections of the survey.

The interviewees were first asked which group of pictures (defined by ‘content categories’) and which individual pictures produced ‘the strongest impression’ on them, and not which pictures they ‘liked’ or ‘disliked’ (32). The five categories of photographs which received the highest statistical responses were: children or children at play (40%); pictures of pregnancy and birth (26%); pictures of the creation of the world (22%); men at work (20%); and pictures of mothers with children (15%) (33). As far as individual photographs were concerned, the list was as follows: the hydrogen bomb explosion (13%); Ruth Orkin’s six-picture sequence of children playing cards (11%); Wynn Bullock’s large image of the light over water at the start of the exhibition (one of the ‘creation of the world’ images) (10%); the images of the Jews being rounded up by German soldiers in the Warsaw Ghetto (10%); the child with a soap bubble by Gjon Mili (8%); and Eugene Smith’s image of his children walking into the garden that closed the exhibition (7%) (34).17

These rankings shift in interesting ways when visitors are asked to list which categories and photographs they most liked and disliked. The categories that made the ‘strongest favorable impression’ were: children at play (39%); pictures of the creations of the world (22%); men at work (18%); images of people playing, drinking and laughing (14%); and pictures of mothers with children (13%) (35).18 The crucial difference between the list of categories that made the ‘strongest impression’ and those that made the ‘strongest favorable impression’ is that images of pregnancy and birth are missing from the second list. This category in fact comes top of those that made the ‘strongest unfavorable impression’ at 13%. The other categories in the disliked list are, in descending order: pictures of war, including the H-bomb explosion (8%); images of cruelty, inhumanity and brutality (7%); pictures of dances (3%); and photographs of hunger, misery and poverty (2%) (35).

A similar pattern of sentiment, political attitudes and sensitivities towards social mores and sexuality emerges in the lists of individual photographs that were liked and disliked. The photographs producing the ‘strongest favorable impression’ were: Orkin’s children playing cards (11%); Bullock’s light over the water (10%); Mili’s child with the soap bubble (8%); Smith’s children in the garden (7%); and Arthur Witman’s American audience laughing at a show (also one of Steichen’s favourite images and the first one he selected for the exhibition) (5%) (35).19 It is worth mentioning that when ‘the total number of responses mentioning pictures with favorable and unfavorable impressions’ were compared, ‘considerably more photos were named as producing favorable reactions than were named as creating adverse impressions’: more than four times as many mentioned pictures producing favourable responses rather than those producing unfavourable impressions (36). Nevertheless, in the ‘unfavorable’ category, two images stood out from all others: the pictures of the hydrogen bomb explosion and of the Warsaw Ghetto were both disliked by 7% of the interviewees each, with all other disliked images receiving statistically negligible responses (36).

What is striking about the pattern that emerges from these responses is that the strongest disapproval and unease was attached to the realms of intimacy, rather than to politics. When asked if there were pictures that they thought should have been excluded from the exhibition, almost one fifth of those interviewed singled out ‘pictures touching traditional taboos, such as childbirth, pregnancy, sex, and love’. Only 6% proposed the Warsaw Ghetto images (38). About a quarter of the respondents indicated that they were ‘undecided’ and the authors of the report rightly note that there were among these ‘probably a number so inhibited as to be unable to express their resentment against pictures penetrating into taboo spheres’. Equally, ‘it might also be that to some of these people the picture of the Warsaw Ghetto represents a taboo in the realm of national life’ (37).

The staff of the American Embassy appear to have had some sense of the images that were likely to meet with disapproval or which were likely to cause unease before the exhibition actually opened in Berlin. At each international site where The Family of Man was shown, the senior Public Affairs Officer of the American Embassy was given final authority over the decision to exclude some pictures if it was thought that these would cause particular offence to local audiences. At many sites, some photos were also added to reflect local culture and society. In Berlin, 16 photographs in total were excluded from the show, and in Munich 12. There was an overlap of only four photographs between the two groups, a fact that supports the claim by the USIS office in Bonn that the reasons for the exclusions ‘were quite definitely only technical ones’, primarily to do with issues of size and space. The one exception to this was Bullock’s large image of a young girl (the photographer’s daughter in fact) seen lying naked and face down among foliage on a forest floor that was hung as part of the ‘creation of the world’ prologue to the exhibition. This particular image ‘was not liked here’ (meaning, one assumes, among the USIS staff in Bonn): otherwise, no ‘psychological, political or ethical reasons existed’ for the removal of the other images.20 The Bullock image would certainly have offended those members of the audience who commented critically in Munich on the images that explored the taboo subjects of intimacy and sexuality. Seen in the company of a photograph of a galaxy from the Lick Observatory, Bullock’s own ‘light over water’, as well as the caption from Genesis (‘And God said, Let there be light …’), the image was clearly meant to represent the birth of humankind embodied in the first woman (Steichen interestingly referred to the image as ‘Lilith’, Adam’s rebellious first companion, rather than ‘Eve’), but the USIS staff may have been right in thinking that the image, encountered so boldly at the very start of the exhibition, might prove too challenging for some of the German audience.21

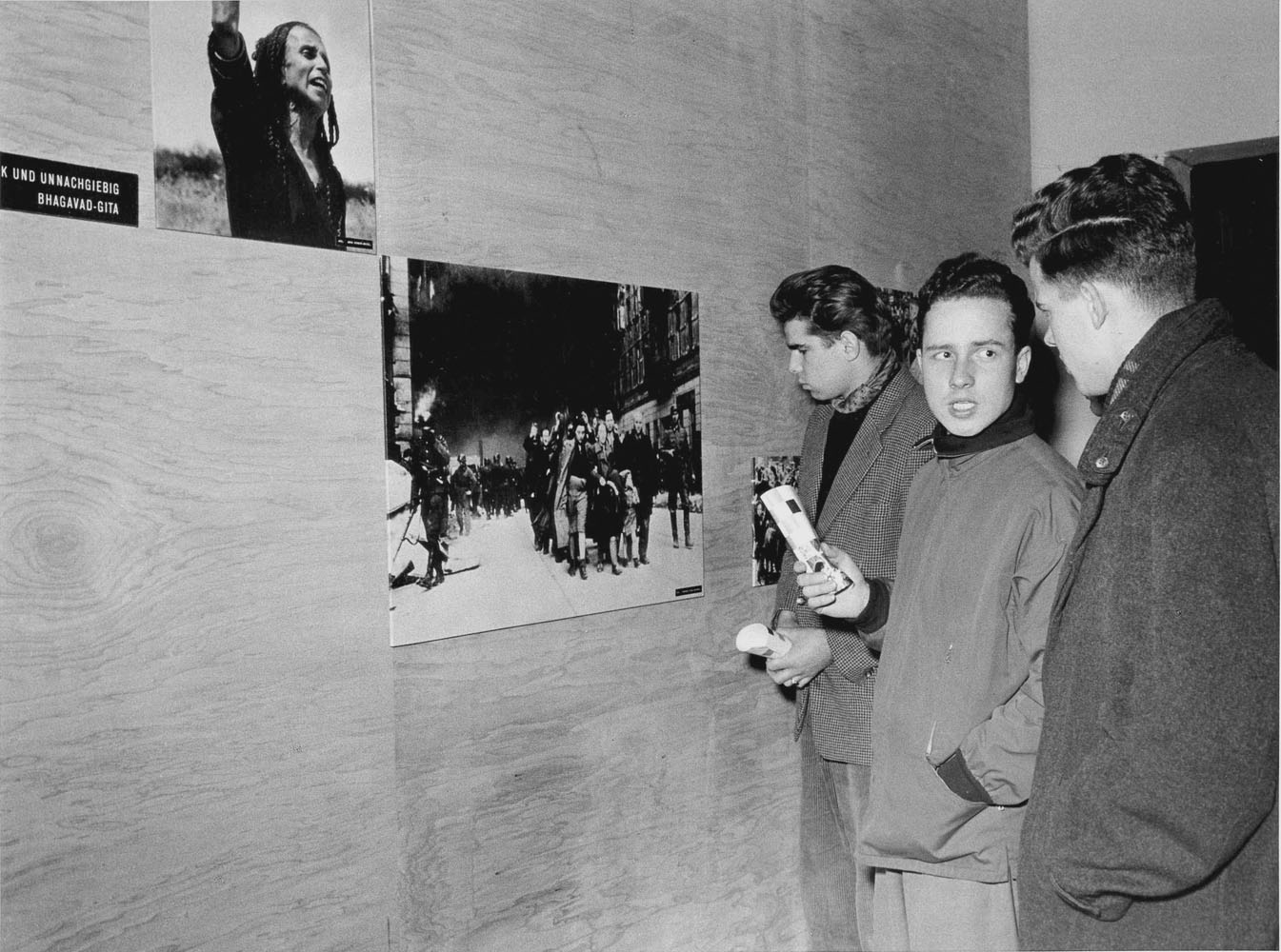

There was also discussion among the USIS staff in Germany about whether or not to exclude the images from the Warsaw Ghetto but Joseph B. Phillips, the chief Public Affairs Officer, ‘finally decided […] to leave it [sic.] in’.22 The decision to let the Warsaw pictures remain in the exhibition proved to be a good one because the visitors’ reactions to these images, perhaps more so than with any other pictures in the show, let us see the traces of the kinds of debate and reflection that were generated by The Family of Man. For example, when visitors were asked which image had made the strongest impression on them, in almost every case the images identified in the exit interviews were less emphatically identified in the home interviews. The only exception to this were the Warsaw Ghetto images which had gained in the strength of impression they had made after visitors had had a few days to reflect on their experience of the exhibition. The photograph of the hydrogen bomb explosion was identified by 17% of those interviewed at the exit of the exhibition as having made the strongest impression on them, but this figure had gone down to 11% by the time of the home interviews. The Orkin photo sequence of the children playing cards also went down, from 13% to 8%. But the Warsaw Ghetto images went from 8% to 12% (34). When visitors were asked whether they detected any nationalist bias in the exhibition, about 10% of the home interviewees (the question was only asked of them) signalled a pro-American bias, and about the same number noted an anti-German one. The comments of the latter group appear to have been focused in particular on the inclusion of the Warsaw images. One visitor commented that ‘the pictures showing the expulsion of the Jews and the photos of the Nuremberg trials were tendentious and placed Germany in a very unfavorable light’. (There were, in fact, no pictures from the trials: the Warsaw images were labelled in Munich, as elsewhere, as ‘Nuremberg trial documents’.) Another said accurately that the pictures ‘showed SS-men in Warsaw, but atrocities committed by other nations weren’t published’ (70). In this case the point was not that the images should not have been included (or that they were ‘tendentious’) but that representations of acts of inhumanity from other nations and cultures should also have been shown – something that The Family of Man in its first iteration at MoMA had done with dramatic effect, and without sparing the US. As Phillips noted in his report, ‘remarks made by individuals as they walked through the display halls were particularly interesting and gave testimony to the emotional impact of this exhibit upon the observer’. He reports one remark in particular, made by a ‘university professor who was with a small group of students’ as they stood in front of the Warsaw Ghetto picture ‘showing children and parents with arms raised at gunpoint’: ‘[…] I don’t know how much more I can impress upon you than that this is something we should never forget […] it is a thing which we must be ashamed of […] but what I want most to say is that some of you perhaps will soon be in uniform, and I want you to remember this: always keep in mind that the army that points guns at little children, that forces little children to raise their arms at gun point, has lost the fight before it ever began […]’23 One of the photographs of the exhibition from Munich shows just such a group of young students as this professor may have been addressing standing before the Warsaw Ghetto images, and in the midst of a discussion (see illustration 15). And it is worth remembering that the notorious Nazi concentration camp at Dachau was not far from Munich.

Sarah E. James, in her study of the photographic cultures of Cold War Germany, East and West, has argued that the remarkable popularity of The Family of Man with West Germans can be put down to the exhibition’s ‘avowedly apolitical stance’.24 James notes, as others have, that in West Germany after the war there was a retreat from politics and the unpalatable realities of the recent past into historical amnesia and the comforting security of the family. Steichen’s celebration, then, of the family and of a universal humanism that supposedly put to one side the challenges of cultural and political difference settled easily into this collective escapism, and also helped to give it support. From this perspective, the injunction by the professor to his students in front of the photographs of the Warsaw Ghetto in the Munich Municipal Gallery not to forget history may seem too isolated and too unrepresentative an instance to serve as a sufficient corrective to this account of the fit between The Family of Man and post-war German culture. But we should remember that the professor and his students were representative of a very high percentage of the exhibition’s audience. James’s account of The Family of Man in Germany relies on a broad characterization of post-war German society as a whole but all segments of this society were not equally and proportionally represented in the audience that came to Steichen’s exhibition. As the Munich survey indicates, the educational level of the visitors was considerably higher than both the average national level and the level of the audiences for other USIA-sponsored shows, and those with a university education made up a far greater proportion of the audience than in the general public at that time in Germany. We cannot then speak about the way The Family of Man would have enabled German citizens to negotiate issues of history and politics without being attentive specifically to the ways these issues would have been discussed and thought about by the more educated members of society. In this respect, the dialogue between the professor and his students about the Warsaw Ghetto images may in fact have been more representative of a larger part of The Family of Man’s German audience than is suggested by James’s account.

15 The Family of Man at the Städtische Lenbach-Galerie, Munich, Germany, 19 November–18 December 1955.

It is true that the survey of the Munich visitors’ reactions to the exhibition does not furnish us with comparable evidence of individual opinion or response because the interviews did not solicit extended comment on particular photographs. But the findings of the survey should nevertheless encourage us to pause and reconsider the broad cultural history James presents, and especially the way in which she formulates the work that The Family of Man did within this history. Only 6% of the interviewees suggested that the images from Warsaw should not have been included in the exhibition. As the survey itself notes, the Jewish genocide was for many Germans a taboo subject, and so some of the visitors may have been reluctant to speak about their reactions to the Warsaw Ghetto photographs. But if this means that the number of people who would have preferred for these images to be excluded from the exhibition was a little higher than 6%, then it must also be the case that the figure for those who indicated that these photographs were the ones that had the deepest impact on them must have been larger than that registered by the survey. Almost a quarter of those interviewed said that the two images from Warsaw and the image of the hydrogen bomb explosion, the most overtly political and historically specific photographs exhibited, were the photographs that made the strongest and most lasting impression on them, with the Warsaw images in fact generating increased reflection for many in the days following the visit to the gallery. It is less important for the present discussion to know what people thought about these images than to know that they did think about them. The photographs from the Warsaw Ghetto were only two images among the 500 or so that made up the exhibition, but Steichen was right to calculate that their startling effect would be disproportionate to their numerical marginalization, that they would force viewers to confront rather than evade history. This is not to say that historical amnesia was not a prevalent reality in post-war West German society; but it does not seem accurate or just to characterize The Family of Man as nothing more than a vehicle for this forgetting.

Equally problematic is James’s claim that, on the one hand, ‘the effort to democratize and Americanize West German culture in the 1950s might have made the exhibition’s blatant American vision more palatable to a broad section of the West German public, or perhaps less glaringly obvious’, and on the other, that Steichen’s show would have been the target of ‘an explicit animosity toward the darker side of American influences’ which was ‘increasingly felt by sections of the West German population, particularly the cultural elite, who decried the growing impact of American popular culture and the subsequent decline of a German Hochkultur (high culture)’.25 The assessment of The Family of Man as an exhibition peddling an ‘American vision’ is widely shared, though almost always presented as a self-evident truth, rather than something that is demonstrated through the kind of discriminating analysis such a judgement requires. What concerns me here more immediately is the continued misfit between James’s contextualization of The Family of Man within West German culture in the 1950s and the findings of the survey of the visitors’ reactions to the exhibition in Munich. According to the survey, over 60% of those interviewed were fully aware that the exhibition was an American production. However, this did not result in either animosity towards the United States, or in the perception that the exhibition was propagating a particularly American vision of the world. On the contrary, the majority of the visitors articulated the view that the exhibition upheld what might be considered universal human values, and that the United States was then the nation disseminating these values more actively than any other.

It may be that such a view of both the exhibition and of America’s international role was naïve, that Steichen’s vision had indeed been made palatable by the very process of Americanization that should have been critically scrutinized. But if this is the case, then we need to both register and explain the fact that the very cultural elite James proposes as the opponents of American influence on West German culture, and as defenders of their own Hochkultur, formed a very large segment of The Family of Man’s audience in Munich, and appear to have given their enthusiastic assent to the exhibition. In this regard, the critical appraisals of the exhibition offered by Wolgang Koeppen and Max Horkheimer, both included for the first time in English in the present volume, provide forceful counterpoints to James’s claims on behalf of the German cultural elite. In the years immediately preceding the first German tour of The Family of Man, Koeppen, who saw the exhibit in Munich, had published an accomplished trilogy of novels exploring Germany’s recent past: Pigeons on the Grass (1951), The Hothouse (1953) and Death in Rome (1954) each tried in different ways to remember and to understand the continuing legacies of this past. And Horkheimer, in collaboration with his Frankfurt School colleague Theodor Adorno, had formulated stringent critiques of modern mass culture that rested on comparisons of fascist Germany and American popular culture.26 The work of neither of these authors could be said to evade history and politics, nor to offer an unqualified or simple-minded endorsement of American culture. And yet both Koeppen and Horkheimer offer an equally enthusiastic affirmation of the humanistic vision of The Family of Man, not because it allows us to forget the challenge of difference, but because it brings us to a sense of human identity through difference.

Notes

1 The information on Berlin is from reports by Dorothea von Stetten, Manager, Exhibition Section, Office of Public Affairs, United States Embassy, Bonn, to Jackie Martin, United States Information Agency (USIA), Washington, DC, 29 September 1955 (Von Stetten to Martin, 29 September 1955); John E. McGowan, Deputy Public Affairs Officer, USIS Berlin, to USIA, Washington, DC, 23 September 1955 (McGowan to USIA, 23 September 1955); as well as an undated typed memo by an unidentified author in the files of the USIA. (The memo gives the attendance figure for Berlin as 44,000.) The details of dates, attendance figures, the opening ceremony and media coverage in Munich, are from a report by Joseph B. Phillips, the United States Information Service (USIS) Public Affairs Office, United States Embassy, Bonn, to the USIS office in Washington, DC, 6 February 1956 (Phillips to USIA Washington, 6 February 1956). For the von Stetten and McGowan reports and the undated memo, Box 1, and for the Phillips report, Box 3, Photographs and Clippings Relating to The Family of Man Exhibition, 1955–1956 (Photographs and Clippings, 1955–1956), Records of the US Information Agency, Record Group 306-FM (RG 306-FM), National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD (NACP). A copy of Phillips’s report can also be found at International Council and International Programs Records, folder I.B.140, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) Archives. Both Phillips and von Stetten note the impressive sales of the book of the exhibition as an indicator of the success of the exhibition.

2 Dorothea von Stetten to Edward Steichen, 28 November 1955, Museum of Modern Art Exhibition Records (MoMA Exhs.) 569.101, Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York (MoMA Archives). Stetten also notes that the press coverage was even more positive in Munich than in Berlin. Professor Guenther Gottwald, Head of the Architecture Department at the Berlin Academy of Creative Arts, and his assistants were responsible for hanging the exhibition in Berlin and Munich. For photographs of the installations of the exhibition in Berlin and Munich, consult Boxes 1 and 3 respectively, Photographs and Clippings Relating to The Family of Man Exhibition, 1955–1956, Records of the US Information Agency, Record Group 306-FM, National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

3 This figure is taken from an exhibition itinerary dated 1 May 1960, in the Edward Steichen Archive (ESA), VB.i.46, MoMA Archives. The Frankfurt, Hamburg and Hanover showings were in 1958 when the exhibition returned to Germany after having been shown in other countries. An itinerary prepared by The Family of Man museum in Clervaux, Luxembourg, confirms the Hamburg date and proposes 1958 as also the year for the Frankfurt and Hanover stops. The Frankfurt date is confirmed by Werner Sollors’s contribution to this volume. There were recommendations that the exhibition be shown in other German cities, including a request as late as September 1960 from the newly founded photography museum in Dresden, then in the ‘Eastern Zone’ where the US had no ‘official cultural exchange agreement’ (Note from Porter A. McCray, Director of Circulating Exhibitions at MoMA, dated 12 September 1960, in the International Council and International Programs Records [IC/IP], VII.SP-ICE-55-10.3, MoMA Archives).

4 Phillips to USIS, 6 February 1956, Box 3, Photographs and Clippings, 1955–1956, RG306-FM, NACP.

5 Foreign Service Dispatch from John E. McGowan, Deputy Public Affairs Officer, USIS Berlin, to USIA, Washington, DC, 23 September 1955, Box 1, Photographs and Clippings Relating to The Family of Man Exhibition, 1955–1956, Records of the US Information Agency, Record Group 306-FM, National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

6 Phillips to USIS, 6 February 1956, Box 3, Photographs and Clippings, 1955–1956, RG306-FM, NACP. Dorothea von Stetten also argued that ‘the most important promotion came from Radio critic Friedrich Luft (RIAS) who is regarded as the pope of the Berlin journalists. What he says is accepted by the Berliners’ (Von Stetten to Martin, 29 September 1955, Photographs and Clippings, 1955–1956, RG306-FM, NACP).

7 McGowan to USIA, Washington, DC, 23 September 1955, Box I, Photographs and Clippings, 1955–1956, RG306-FM, NACP.

8 The report on ‘Visitors’ Reactions to The Family of Man Exhibit’ is dated 23 January 1956 and, along with a number of other reports from Germany compiled by the USIS, can be accessed via the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s library website. The Family of Man report can be found at http://libsysdigi.library.uiuc.edu/OCA/Books2009–10/visitorsreaction225unit/ (accessed 18 July 2016). All page references to the survey will be given in the text. Other reports, such as those on the ‘Space Unlimited’ exhibition, or ‘West German Perspectives on US Culture and Politics’, can be found by searching for ‘U.S.I.S.’

9 One reason for the high attendance was that ‘because of circumstances peculiar to Berlin, no entrance fee was charged’. It was also estimated that on 7 October, which was an official holiday, half of all visitors were from the GDR (Foreign Service Dispatch from John E. McGowan, Deputy Public Affairs Officer, USIS Berlin, to USIA, Washington, DC, 20 October 1955). According to an ‘Operations Memorandum’ sent by USIS Bonn to the Washington head office (10 January 1956), Brecht, ‘famous East-zone pro-communist playwright’, was photographed by a ‘Berlin student’ while visiting the show. For the dispatch and memorandum, and also the photograph of Brecht, Box 1, Photographs and Clippings relating to The Family of Man exhibition, 1955–1956, Records of the US Information Agency, Record Group 306-FM, National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. For Richter, see the video and transcription of his conversation with Nicolas Serota (dated 11 October 2011) at: www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/video/gerhard-richter-panorama (accessed 18 July 2016). Speaking of how ‘terrible’ life was in the East, and how restricted personal freedom was, he also recalls that there was ‘the possibility to go every year at least twice to West Berlin’ to see ‘movies and exhibitions’. It was on one such trip that he saw The Family of Man: ‘This was a real shock for me, this show […] to see these pictures, because I knew only paintings […] they showed so much and they told so much these pictures, these photographs, told so much about modern life, my life.’ Richter dates his own interest in photography from this moment when he encountered Steichen’s exhibition because it showed him the ‘power’ of photography and ‘what photography can do’.

10 On East German responses to The Family of Man, see Sarah E. James, Common Ground: German Photographic Cultures Across the Iron Curtain (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013), 61–3. James notes that though the exhibition was viewed critically by some sections of the East German authorities, in general the reception in the media and by the public was positive.

11 The Mexico City survey is a report on visitor reactions similar to the Munich report, though much shorter and less detailed. It was commissioned by the US Embassy, and is based on 636 oral and written interviews conducted during October and November 1955. ‘The Family of Man: A Study of Audience Reactions’, Box 16, International Survey Research Reports, 1953–1964, Records of the US Information Agency, Record Group 306, National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. My thanks to Anke Reitz for sharing this document with me. The findings of this document are, in some ways, very similar to those from Munich; they will be examined in a longer discussion of audience reactions elsewhere.

12 Phillips to USIA, Washington, DC, 6 February 1956, Box 3, Photographs and Clippings, 1955–1956, RG306-FM, NACP.

13 Milton Leavitt, Assistant Public Affairs Office, US Embassy, Munich, to Jackie Martin, USIA Washington, DC,15 February 1956, Box 3, Photographs and Clippings relating to The Family of Man exhibition, 1955–1956, Records of the US Information Agency, Record Group 306-FM, National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

14 Steichen was in Munich on 20–21 September. For details of the visit, see report from Leavitt in the Foreign Service Dispatch, 18 October 1955, from USIS Bonn to the Department of State, Washington, DC, Box 3, Photographs and Clippings relating to The Family of Man exhibition, 1955–1956, Records of the US Information Agency, Record Group 306-FM, National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. The text of Leavitt’s speech from the Munich opening can also be found here.

15 Some 61% of those interviewed were men, whereas men only made up 45.6% of the general population. Some 39% of the interviewees were women whereas women made up 54.4% of the general population. It is also interesting to note that while unmarried individuals made up just under 24% of the population, they accounted for 54% of the interviewees, and although 63.5% of Germans were married, this group accounted for only 37% of those interviewed. Of the interviewees, 38% were aged between 20 and 29, and 55% were 30 and above (2).

16 There was a slightly greater differentiation among men and women: 48% of men said they liked the show ‘extremely well’ and 38% said ‘very well’; among women the numbers were 55% and 36% (10).

17 For these photographs, see Edward Steichen, The Family of Man (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1955), title page (Bullock’s ‘light over water’); 40 (Orkin); 165–6 (Warsaw Ghetto, though the book of the exhibition only includes one of the two images from Warsaw in the exhibition); 189 (Mili); and 192 (Smith).

18 One reason why the images of children at play made a particularly strong impression may have been because the exhibition in Munich was, as von Stetten claimed, better hung and more dramatically and effectively lit than in Berlin. In her letter to Steichen she noted in particular the ‘great impact’ of the ‘contrast between the serious sections’ dealing with topics such as ‘Atomic Energy’ or the ‘United Nations on the one hand, and the playing children on the other. The latter has such an exuberant gaiety and brightness which I feel was lost in the somewhat subdued Berlin room’ (28 November 1955, MoMA Exhs., 569.101, MoMA Archives).

19 For the Witman image, see Steichen, The Family of Man, 109.

20 Operations Memorandum, 20 December 1955, from USIS Bonn, to Jackie Martin, USIA Washington, DC, Box 3, Photographs and Clippings relating to The Family of Man exhibition, 1955–1956, Records of the US Information Agency, Record Group 306-FM, National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. The memorandum lists all the images excluded by number. I have not found lists of any images that were added in Berlin or Munich. For Bullock’s image of the naked girl, see Steichen, The Family of Man, 5.

21 On Steichen’s referring to the image as ‘Lilith’, see his letter to Wynn Bullock, 28 December 1954, MoMA Exhs., 569.5, MoMA Archives. Steichen acknowledged receipt of the image negative and wrote, ‘The child will be used as leading into the prologue of the creation. I am inclined to label the picture of the child as Lilith.’

22 Von Stetten to Martin, 29 September 1955, Photographs and Clippings, 1955–1956, RG306-FM, NACP. It is clear from the installation photographs that there were two photographs from the Warsaw Ghetto in Munich, but this note, like some of the other documents relating to the exhibition in Germany, refers to a single image. One of the Warsaw images, of the little boy with his arms raised, was also not included in the book of the exhibition. In a reply to von Stetten, Martin says she has ‘the interesting story concerning the use of the Warsaw Ghetto photo in the Berlin showing’ from Steichen but she gives no further details (Jackie Martin to Dorothea von Stetten, 22 November 1955, Box 1, Photographs and Clippings relating to The Family of Man exhibition, 1955–1956, Records of the US Information Agency, Record Group 306-FM, National Archives at College Park, MD).

23 Phillips to USIA Washington, DC, 6 February 1956, Box 3, Photographs and Clippings, 1955–1956, RG 306-FM, NACP.

24 James, Common Ground, 62.

25 Ibid.

26 See in particular the chapter on ‘The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception’, in Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, Dialectics of Enlightenment (New York: Social Studies Association, 1944).