It obeys no architectural rules, it embraces no conventional materials and follows no accepted scheme of color. Its shape, if anything so eccentric can be entitled to that appellation, is an irregular oblong. . . . Its color is a grim and forbidding black, enlivened by the dull lustre of myriads of metallic points . . . the uncanny effect is not lessened, when, at an imperceptible signal, the great building swings slowly around upon a graphited centre, presenting any given angle to the rays of the sun and rendering the apparatus independent of diurnal variations.

—W. K. L. Dickson and Antonia Dickson (1895)1

IN LATE 1892 at Thomas Edison’s laboratory in West Orange, New Jersey, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson designed an architectural space like few seen before. Soon dubbed the Black Maria—a colloquialism for police paddy wagons—the building was variously described by contemporary observers as a coffin, cavern, or outright conundrum. Today it is better known as the world’s first film studio. Dickson developed the studio concurrently with two of Edison’s better-known moving-image machines, the Kinetograph and Kinetoscope, and the studio was integral to Dickson’s work on these devices. Each operated on the same principles: the juxtaposition of light and dark, the interplay of movement and stasis, and the technological reproduction of nature. Much like the camera and projector, studios like the Black Maria allowed Dickson, Edison, and the inventors, artists, and image-makers who followed to create new forms of visual representation and to contribute to the emergence of new conceptions and experiences of modern technological space.

The Black Maria remains an often-celebrated icon of early film history and a companion “first” to Edison’s moving-image apparatuses. Unlike those devices, however, historians and theorists have paid insufficient attention to its formal genealogy and, as a result, its importance for theorizing film space.2 Indeed, observers dating to Dickson himself have too quickly accepted the idea that the studio was simply a singular, idiosyncratic form, and that “modern” studios soon made its “primitive” design little more than a souvenir of film history. Such characterizations deny the complexity of the structure’s form and function, its historical roots, and the spatial predecessors that contributed to Dickson’s design. These spaces—which included the Edison laboratory, Eadweard Muybridge and Étienne-Jules Marey’s respective research laboratories, photography studios, and civil engineering designs—point to the varied artistic, architectural, scientific, and technological contexts that guided early cinema’s development.3

By examining the spaces and forms that influenced the Black Maria’s design, the films produced in the studio, and the studios and films that came after it, this chapter argues that cinema emerged as a key component of a broad reformation of the relationship between nature and technology in the late nineteenth century. Beginning with Lewis Mumford in the 1920s, historians of technology have argued that the turn of the twentieth century marked a new stage in the greatest technological revolution in history: the construction of an artificial world founded not simply on our domination and exploitation of nature through machines, but rather on nature’s outright replacement by human-built technological environments.4 The devices and materials undergirding this new technological world emerged from late-nineteenth-century research laboratories such as Edison’s. Here, the craft-shop model of collaborative labor and invention encouraged overlaps and intersections among new inventions that helped lead to the production of the broad technological systems that shaped industrial modernity.

Cinema should be understood as a significant component of that process. The film technologies that emerged from the laboratory would offer a powerful system of world-building of their own, with the studio as their spatial locus. At the Edison laboratory, the problem of inventing cinema became not simply a question of creating a camera or projector but also an architectural problem of producing the necessary space for capturing movement. The Black Maria was Dickson’s solution. The result went beyond mere motion capture; it also defined an aesthetic form and the conceptual frame for a modern type of technological space—film—that would be no less technological in its future studio and non-studio forms.

While the Black Maria may be the best example of the film studio’s direct link to the laboratory, the studios that followed should equally be understood as technological spaces, or as machines. From their origins, the first studios were designed to defy the dictates of day, night, weather, and location in order to frame the production of artificial environments. This framing produced a version of what Martin Heidegger described as “enframing”—the process by which technologies extract “the energies of nature” and place them on reserve.5 The Black Maria, this chapter argues, enframed sunlight as a raw material needed to activate the chemical processes for recording movement. Edison filmmakers such as Edwin S. Porter and James White used the studio as one key component of the basic apparatus for producing literal versions of Heidegger’s metaphoric “world picture”: films that set the world before the human subject and rendered it knowable as a series of moving images.6

THE BLACK MARIA: STUDIO, MACHINE, UNKNOWN FORM

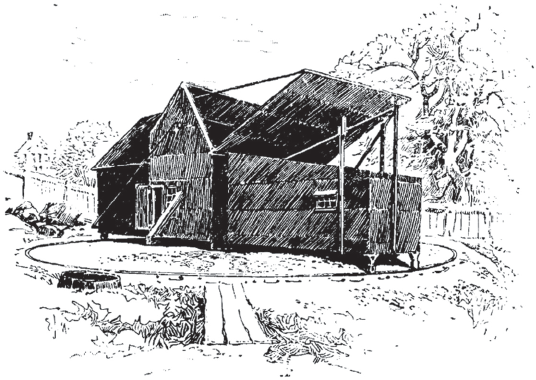

The few existing images of the Black Maria may explain the tendency among observers, critics, and historians to disparage the studio’s “primitive,” “rudimentary” form, while variously describing it as a “dismal-looking affair” and a “rambling building of cheap construction.” In one of only three known photographs of the studio’s exterior (fig. 1.1), reportedly taken in 1903, the structure appears as a ramshackle hodgepodge of geometric forms, crudely cobbled together and ready, at any moment, to collapse into only so many odd building blocks and irregular detritus.

Within only a few years, the seldom-used and now-dilapidated building would indeed be demolished, perhaps taking its place, like so many provisional machines and outworn technological spaces, alongside the discarded railroad wheel posed in the photo’s foreground. Only a few years earlier, however, the studio was the center of Edison’s film production and a hive of laboratory activity. In its more than half a decade of use beginning in 1893, the studio framed the production of thousands of films featuring contemporary vaudeville stars, local performers, miscellaneous celebrities, and Edison lab employees.

Dickson developed the studio’s design in late 1892 as part of the laboratory’s preparations for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Edison hoped to feature a series of Kinetoscopes there, and Dickson recognized that a dedicated production space with good lighting would be necessary to furnish these machines with sufficient films.7 A team of laboratory staff, led by John Ott, one of the laboratory’s most skilled machinists, and several freelance carpenters assembled the studio according to Dickson’s design during the winter, completing the job in February for a total cost of $637.67.8 It was built of wood covered in tarpaper (a material typically used for waterproofing roofs) attached with tin nails, and extended approximately fifty feet in length and fifteen in width, with a height varying from seven to twenty-two feet (fig. 1.2).9

Far from being primitive in form, the studio had a complex design for capturing sunlight, highlighting moving objects for the Kinetograph, and facilitating efficient film production by increasing the available working hours and providing consistent, specialized workspaces for shooting, developing, and processing films. Dickson placed the studio stage beneath two perpendicularly intersecting gabled roofs, the taller of which rose to twenty-two feet and could be opened on one side to admit sunlight. Behind the stage, the lower 18-foot roof covered the “black tunnel” that gives the Black Maria films their distinct black background. On the other side of the stage, just beyond the roof opening, Dickson added a 9 × 7 foot darkroom for loading and unloading film from the Kinetograph, which could be mounted on tracks running between the darkroom and the filming area. The entire structure was mounted on a central graphite pivot with wheels at each corner, perched on a circular track. Using two large boards extending from the center of either side, several workers could rotate the studio in order to adjust the angle of sunlight illuminating the stage through the open roof.

As performers and the press began to visit in 1893, the studio, initially referred to simply as the “revolving photograph building” or the “Kinetographic Theatre,” quickly acquired both a new moniker and a reputation for being an especially strange structure, even at the Edison laboratory. Lab personnel coined it the “Black Maria” after judging that the studio bore closest resemblance to police vehicles of the same name.10 For Dickson, the studio resembled a “medieval pirate-craft,” and its interior evoked images of dungeons, torture, and death.11 Likewise, Edison Company lawyer Frank Dyer recalled the studio’s “lugubrious interior,”12 and one press report noted that it “reminded everybody of a huge coffin.”13

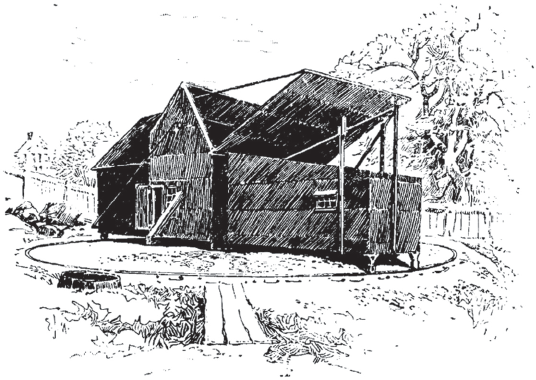

Contemporary illustrations such as Edwin J. Meeker’s ink drawing (fig. 1.3) for an 1894 Century Magazine article by Dickson and his sister, Antonia, must have reinforced such descriptions. In Meeker’s drawing, the studio appears slightly elongated, and the darkroom’s exaggerated length indeed helps evoke the shape of a casket. The lightly sketched, spare landscape stands in sharp contrast to the darkened studio’s imposing presence. Meeker’s shading lines on the building’s forward section parallel the open roof, creating a sense of movement into the interior, as if the studio might swallow elements of its surroundings.

In what might be read as a visual metaphor for the process by which modern technology, in Heidegger’s theory, extracts energy from nature, an adjacent tree dangles over the open roof, bending as if it were being sucked into the studio.14 To the left, a darkly shaded stump suggests both the Black Maria’s material origins and nature’s future fate at the Edison lab, where trees were just as likely to become picket fences, bridges, or studios. The wood-plank bridge in the immediate foreground further inscribes such an idea of progress into the image, both by offering a crude counterpart to the studio’s modernity and by recalling Dickson’s comparison of the studio to another modern nineteenth-century technology, the swinging river bridge.15

The uncertainty and imaginative creation expressed in Dickson’s and other witnesses’ early attempts to associate the new building with some familiar form suggests not so much the building’s inherent strangeness as the novelty of the film studio. While a more conservative observer could very well have described the Black Maria as a strange but not altogether unworldly pitched-roof house in need of windows and paint, its status as a film studio—a previously unknown entity—contributed to doubts about its form and function. Indeed, like the motion picture machines used in it, the studio represented a novel invention and an unfamiliar technology whose sources of inspiration and formal influence remained unclear. Contemporary observers did not have to look far, however, to find more precise models for the studio’s design, both in the Edison laboratory itself and in the technologies produced there. Like other contemporaneous sites of cinematic invention, the West Orange laboratory framed early cinema’s technological ontology. Within and according to the principles of these laboratories and workshops—the first “studios” of sorts—cinema’s inventors and first practitioners developed an idea of what cinema would become.

LABORATORIES, WORKSHOPS, ATELIERS—ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROL IN THE FIRST “STUDIOS”

You can’t help but have noticed that Boulevard cafes aspire to become successors of the Faculté des science. Below the room where one drinks glasses of beer, there is a basement in which highly decorated gentlemen perform lectures and experiments on cinema, the praxinoscope, and radiography. Enter: there are vials, batteries, accumulators, wires, and tubes: it is the laboratory.

The laboratories and workshops where scientists, inventors, technicians, and tinkerers created the first film technologies became not only early exhibition sites but also, by default, the first film production spaces. From Lyon, Berlin, and Leeds to New York, Washington, D.C., and rural New Jersey, spaces of technological research and development yielded the first fragments of moving images. Like the early photographers who reproduced scenes in and from their workshops, the first filmmakers made their workspaces and themselves early test subjects for new film technologies. The spaces and machines with which they worked and the images they produced developed in tandem. Together, they helped establish the aesthetic form and content of early moving pictures and created the initial norms that defined studio film production, norms which first emerged in a more general culture, practice, and spatial model of laboratory research and development.17

The professional research laboratory became a key site of scientific and technological creativity and labor in the nineteenth century. Experimental labs and workshops have existed in varying forms since at least the seventeenth century. But only in the early 1800s in Western Europe and by the second half of the century in the United States did scientists and inventors institutionalize distinct spaces of experimentation, research, and development.18 Fueled by industrialization and the increasing rigor of empirical science, laboratories found institutional support from governments, universities, and corporations, and they quickly became potent symbols of modern industrial society.19

The design principles developed in early laboratories would come to condition early studio “laboratories” like the Black Maria. First in chemistry, then in fields such as physics and astronomy, scientists established norms for these physical spaces according to the practices of scientific research, teaching, and training. In order to obtain rigorous and replicable experimental results, they focused on producing highly coordinated and controlled spaces with consistent temperatures and architectural stability. Architects met these requirements through close attention to building orientation—to control temperature in relation to solar trajectories—and material structure, including the use of deep support columns for increased stability, concrete foundations to control ground temperature, and nonmagnetic materials to avoid interference with experiments and machines.20

Like their scientist counterparts, inventors such as Edison followed similar principles to create private industrial research laboratories. They profited from the growing market for invention that drove the development of the engineering profession and innovation in major technological systems such as the railroad and telegraph. In the second half of the nineteenth century, support for industrial research developed on a wide scale with laboratories such as Edison’s at Menlo Park.21 Established in 1876, the Menlo Park lab, which Edison famously dubbed an “invention factory,” became a model for the organization of the first generation of modern research laboratories in the United States.22 Combining the shop tradition of collaborative labor and experimentation with specialized machines, highly skilled craftsmen, and workers versed in pure and applied sciences (supported by a large library collection), Edison aimed to streamline invention into a profitable enterprise.23

By 1887, when he moved the laboratory to West Orange, Edison had developed a system of small-scale invention supporting specific consumer industries and existing contracts that he used to fund the lab’s larger development projects, which included the still-developing electrical industry, magnetic ore-separation, and the electric storage battery.24 At West Orange, he would use his earnings from the electrical lighting business, his experience from Menlo Park, and modern principles of laboratory design to create the most advanced research laboratory in the world. The lab’s spatial organization, material design, and culture of experimental practice would ultimately determine the material and spatial character of the world’s first film studio.

THE EDISON LABORATORY, WEST ORANGE, NEW JERSEY

In 1897, Edison appeared in a film that seemed to offer its viewers a rare behind-the-scenes glimpse of the world of invention he had created in West Orange. The film, Mr. Edison at Work in His Chemical Laboratory, presents a lively, lab coat–clad Edison, surrounded by all the trappings of a scientific laboratory and in the midst of an unknown chemistry experiment. Whatever the film’s viewers may have been led to believe, the film was not filmed in the chemical laboratory. Although the film’s producers, James White and William Heise, may have modeled the set from a well-publicized photograph of Edison in the laboratory’s chemical building, they produced Mr. Edison’s “experiment” a few steps away in the more suitably lit Black Maria. The studio was no chemical laboratory, but it was no less a space of experimentation. Indeed, in transposing the chemical lab to the film studio, White and Heise restaged a process that had already taken place half a decade earlier. As Dickson searched for the technologies, experimental practices, and spaces that would lead to the creation of motion pictures, he found inspiration and models throughout the West Orange laboratory.

For historian of technology Thomas Hughes, early inventors such as Edison were “like avant-garde artists resorting to the atelier” where they could be free to create “a new way, even a new world, to displace the existing one.”25 If the West Orange lab was Edison’s “new world,” the technologies produced there were aimed at not simply displacing the world outside, but replacing it with a modern technological environment. From within the artificial spaces of the laboratory, Edison contributed machines, materials, and techniques for a new vision of industrial modernity. The Black Maria and the films produced in it paralleled that project. The studio, operating according to the same principles as the lab around it, produced an artificial environment and a series of technological products that contributed to a broad process of technological change based on environmental mastery, control, and mechanical reproduction.

For the West Orange lab, Edison initially envisioned, in Hughes’s words, “a monumental and prestige-enhancing building in the French mansard style” that would hide its technological function behind an impressive façade (a strategy, discussed in chapter 3, that Edison would later use for his film studio in the Bronx).26 He entrusted the design to New York–based architect Henry Hudson Holly, who had also built Glenmont Estate, Edison’s new home on the hill above the laboratory. Holly transformed Edison’s rough proposal into a more traditional three-story factory design, retaining the spirit of prestige from Edison’s design by decorating the building’s principal façade with three two-story arched windows.

Behind this public face, Edison planned a dynamic space of invention with an encyclopedic collection of materials and objects, specialized rooms for every branch of science and engineering, and flexible spaces for improvised experimentation and collaboration.27 Recognizing that a single 250 × 50 foot structure would not be sufficient, Edison reconceptualized the laboratory as a multibuilding campus with an interior courtyard, surrounded by an exterior wall. The design, which Edison entrusted to a new architect, Joseph J. Taft, added four specialized buildings, each 100 × 50 feet, arranged perpendicularly to the main building.28

These four buildings—originally housing a galvanometric workshop, a chemistry lab, a pattern-making and carpentry shop, and a metallurgical lab—were designed according to principles derived from nineteenth-century laboratory standards. The galvanometric building, in particular, strictly conformed to common guidelines for architectural stability and magnetic purity to facilitate electrical experiments requiring high degrees of precision. Taft built the structure using nonferrous materials, including copper for the nails and pipes and granite for the roof. The building stood on deeply lain brick pillars topped with black marble and a concrete floor, and it was isolated from the other buildings by a courtyard.29

The laboratory opened in 1887 with a staff of approximately seventy-five men led by four main experimenters, including Dickson, who also served as the lab’s photographer.30 It operated on a model of versatility, both in terms of its personnel (who collaborated in experimental teams on multiple simultaneous projects) and its spaces of experimentation (which shifted function to accommodate different areas of research).31 The machine shops, in particular, became central sites through which experimenters routed their designs and prototypes.32 The laboratory housed machine shops on the first and second floor of the main building. Surrounding the second-floor shop, Edison arranged a series of experimental rooms assigned to specific projects, initially including Dickson’s ore-milling experiments. Among these rooms was also the so-called “photographic room,” Number 5, where Dickson conducted the first motion picture tests.33

The versatility of the laboratory and its personnel, combined with the overlap between projects created by spatial proximity and multitasking, left a mark on all of the lab’s products.34 Cinema was no exception. The Kinetoscope and Kinetograph were shaped by the interactions of Edison employees engaged simultaneously in broadly diverse areas of research that ranged from ore milling (Dickson), electric lamps (Charles Brown), and telegraphy (William Heise) to precision electrical testing (Arthur Kennelly), the phonograph, and precision machine work (John Ott).35 Edison’s early idea of recording images on a rotating cylinder, for instance, derived from the lab’s common use of cylinders in such devices as the phonograph and telegraph. In his second motion picture caveat (1889), Edison proposed using a common chemical laboratory tool, the Leyden jar, to illuminate objects for recording.36 And when Edison and Dickson shifted from the cylinder design to a system involving strips of celluloid film, they fell back on their familiarity with moving strips of paper through the automatic telegraph machine.37 Just as these various machines and experimental devices transformed the experience of industrial modernity, so would the cinematic technologies to which they helped give form.

The first film studio developed through a similar form of appropriation. In a series of spaces developed between 1889 and 1892, Dickson drew on a range of sources, many at the lab itself, to craft a controlled space of experimentation—a technological environment—suitable for photographically reproducing movement efficiently and on a large scale. While these spaces differed in form, their function remained consistent. They were sites of both image production and continuing technological development, an imperative that helped condition their photographic and cinematic products.

FROM ROOM #5 TO THE BLACK MARIA: PRODUCING SPACES AND IMAGES IN WEST ORANGE

Dickson’s motion picture experiments began in the room set aside for his work as the West Orange laboratory photographer, Room #5.38 Unlike many parts of the lab, the room remained locked, and during experiments lab personnel reportedly had to pass notes, supplies, and food through a small portal.39 As Paul Spehr suggests, this strict regulation may have been due to the secret nature of Dickson’s motion picture experiments. But it was just as likely an effort to protect the sensitive chemicals and photographic negatives housed there. This attention to the effects of light and its necessary regulation would be the key feature and driving force behind Dickson’s designs, first for an outdoor photography area and photographic studio, and, ultimately, for the Black Maria. Through these successive spaces, Dickson transposed the strict attention devoted to environmental control at the laboratory into the film studio and its practices.

Dickson designed the exterior photography area and the so-called “photographic building” in 1889 while Edison was in Paris for the Exposition Universelle. These new structures may have become necessary due to the problem of vibrations produced by the machine shops and elevator adjacent to Room #5. More importantly, the room’s windows did not provide sufficient light for Dickson’s advancing motion picture experiments.40 Although Dickson had already used arc lights in his role as laboratory photographer and experimented with light from laboratory tools such as the Leyden jar and Geissler tube in his motion picture tests, these artificial sources of illumination remained too weak for satisfactory rapid exposures.41 Dickson needed a better-lit and controlled area in which to continue his tests, and he found inspiration in several sources: contemporary photography studios, Eadweard Muybridge’s Animal Locomotion plates, and Étienne-Jules Marey’s Station Physiologique.42

There can be little doubt that Dickson consulted, perhaps first, the laboratory’s copy of Matthew Carey Lea’s A Manual of Photography (1868), a well-known publication at the time with a section outlining plans for a photography studio, or “glass room.”43 Lea’s diagrams offered three variations on a structure providing “front-upper-side light” through glazed openings.44

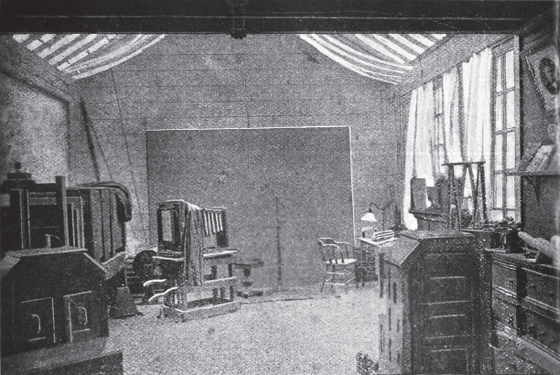

For the photographic building, Dickson created a slightly altered version of these models. His design consisted of two main sections: the 18 × 20 foot studio and an adjacent, two-story portion with two darkrooms on the first level and a projection room above. The studio area had a gabled roof, glazed on both sides but joined by a solid brick support across the center, with sliding glass windows covering one wall.45 The building was conveniently located adjacent to the metallurgical building where Dickson conducted his ore-separation experiments, and several freelance builders began working on it in August 1889.46

During the new building’s construction, Dickson designed and built a second, exterior area in which to continue his experiments. Although few details about this facility remain, Dickson reportedly also built it along the side of the metallurgical building and may have continued its use even after the photography studio’s completion.47 The inspiration for this setup came, most likely, from Muybridge and Marey. Edison received a selection of Muybridge’s plates in November 1888 that one lab worker later remembered being displayed in the library for “some months” afterwards.48 As Dickson may have learned from Muybridge’s earlier 1888 lecture in Orange, New Jersey, or during Muybridge’s subsequent visit to the Edison laboratory, Muybridge photographed his motion studies against a black cloth hung against a wooden structure built at the University of Pennsylvania in 1884.49 Dickson may also have been aware of Marey’s exterior shooting method, which, although more advanced by 1889, began similarly with a plain black cloth suspended on a wooden frame with movable panels.50 While this exterior space gave Dickson the bright light he lacked in Room #5, it did not offer the environmental control that came with the photographic studio. Dickson’s move inside anticipated similar shifts by later filmmakers who began filming on exterior sets before moving indoors to escape the vagaries of wind, rain, and snow.51

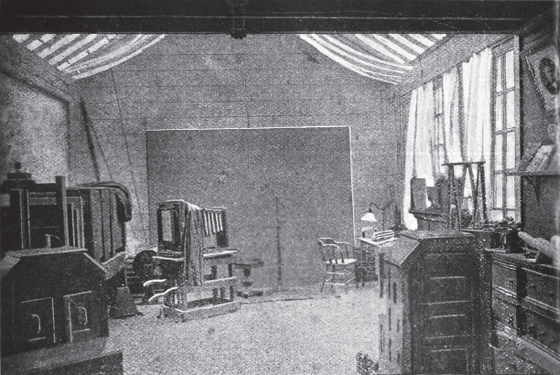

The new photographic building, completed in late September or early October 1889, seemed to promise the conditions Dickson desired. An interior photograph (fig 1.4) of the studio area shows that he equipped the room with shades for controlling sunlight and a flat black background similar to the one probably used for the exterior shed.52 In a preview of the Black Maria’s later use, the building became a site of both image production and continued experimentation. While Dickson regularly took advantage of the new studio’s improved lighting conditions in his capacity as laboratory photographer, the building’s main purpose remained the motion picture experiments, which advanced in late 1889 as Dickson and his assistants—working in both Room #5 and the new building—adapted the motion picture machines to use new Eastman film stock.53 After a hiatus during which Edison and Dickson refocused their efforts on the ore-milling project, the motion picture experiments again accelerated in the latter months of 1890.

During 1891 Dickson shifted his efforts to producing moving images in the photographic building.54 The film fragments that survive offer an early glimpse of the image form produced by Dickson’s evolving studio architecture. Like Marey’s early motion studies, Dickson and his new assistant William Heise’s films feature figures in white set against stark black backdrops that dominate the frame. The photographic studio frames an artificial space designed to efface itself in favor of a new space—the space of the image rendered mechanically through the precise recognition of light reflected by moving figures. The success of the environmental control in the laboratory is registered here by the clarity of the figures outlined against an empty backdrop.

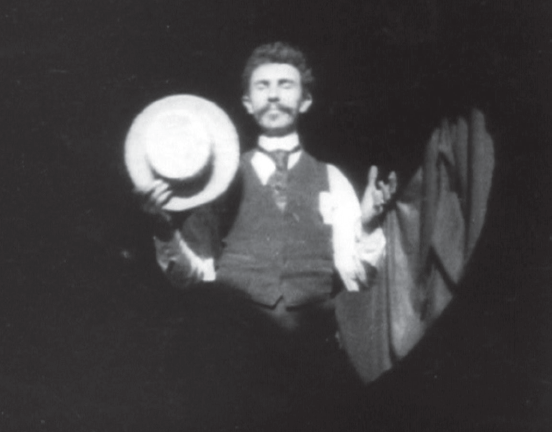

An early camera test known as Dickson Greeting (fig. 1.5) offers a reflexive example of the artificial reality that Dickson discovered in his experimental photographic laboratory-studio. In this prototypical early lab image, Dickson doffs his hat to test his own recognition by the reproductive apparatus. His greeting addresses the viewer in an act of acknowledgment—“attracting” attention. But it also points up the success of the image’s spatial effect—the creation of a lifelike technological world in miniature.

The success of these early tests and further advances in the Kinetoscope, Kinetograph, and the processes for developing their films led to new efforts to expand film production. Despite this success, however, Dickson recognized that the photographic building would not be suitable for further testing and image production. While the photo studio offered a degree of control over the filmmaking environment, it was not versatile enough for large-scale production and high enough quality images. Dickson lamented, in particular, the appearance of side shadows caused by the studio’s fixed position relative to the sun.55 He designed the Black Maria to solve this and other problems by returning to his earlier sources—Lea’s Manual and Marey’s Station Physiologique—combined with a new set of ideas about how to regulate the experimental space more precisely.

A NEW DESIGN FOR ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROL

Dickson’s design for the Black Maria shared characteristics with the earlier photographic building, but it also marked a profound and somewhat surprising break with its predecessor. Rather than designing a better equipped and positioned “glass room,” Dickson chose to abandon glass altogether, a move that materially distinguishes the studio from the majority of those that appeared over the next two decades. Such changes did not, however, alter Dickson’s principal goal and the studio’s basic purpose: precise environmental control for both image production and technological experimentation.

Dickson’s primary concern appears to have been reflecting the brightest light possible at an exact angle from the figures on the stage back to the Kinetograph’s lens. The new studio would thus be, first and foremost, a highly refined machine for regulating light. For this purpose, he needed a more dynamic structure than the photography studio. Dickson introduced four major changes to the previous design: (1) he rejected the transparency of glass in favor of the most opaque isolation possible, hidden beneath a retractable roof; (2) he subtly transformed the roof’s shape to direct light more precisely onto the stage (and perhaps in an effort to help control heat in the enclosed space); (3) he traded the flat black background used in the photographic studio in favor of a “black tunnel” like the one used by Marey; and (4) he made the entire structure mobile, allowing it to be rotated according to the position of the sun.

The new roof design most likely came, once again, from Lea’s Manual of Photography.56 In the same section detailing methods for constructing a “glass room,” Lea offers several design variations for moderating high temperatures. As later accounts show, visitors often complained about the sweltering heat in the Black Maria, a problem that Dickson may have anticipated from the beginning, perhaps due to excessive heat in the photographic building. While contemporary drawings of the studio often omit this feature, photographs of the Black Maria (as well as a diagram drawn by Dickson later in life) show a gap between the peak of the studio’s roof and the opening of its retractable portion. This design roughly corresponds to Lea’s suggestion for regulating the temperature by leaving a “space between the southern slope of the ridge and the ceiling on that side.”57 Although Dickson’s design would not have produced the exact effect that Lea proposed, it did restrict the amount of light entering the studio to the smaller area of the stage, thus reducing solar exposure and shaping the future films’ aesthetics by determining the outline of the filmable space.

Dickson’s decision to opt for an open-air roof rather than creating a glass covering may also have been motivated by a desire to regulate temperature. He would have recognized that enclosing the studio on all other sides would already reduce the effects of wind, and at this early date rainy conditions would halt filming even in a glazed studio. More likely, however, Dickson’s choice was driven by cost, speed, and weight. Ordering custom glass for his design would have been much more expensive and taken too long for the studio to be completed in time to produce films for the upcoming exposition in Chicago. More importantly, glass would have made it difficult to rotate the studio, thus hampering its most novel and, for Dickson, most crucial function.

The ability to rotate the studio according to the position of the sun would allow Dickson to avoid the problem of side shadows that plagued his productions in the photographic studio. Such control became necessary because Dickson’s evolving recording device required more exposures per second and thus even more light on the filmed subjects.58 Ensuring that all of the sunlight admitted to the studio would reach the stage at an exact angle was thus crucial to Dickson’s success. In order to achieve this result he sought a radical solution: synching the studio’s operation with the movement of the sun. By “rendering the apparatus independent of diurnal variations,” as he would later describe, Dickson highlighted a profound and lasting tension in cinematic production between control of and reliance on the natural environment.59 This tension mirrored the conditions of scientific experimentation in the surrounding lab, where architectural materials and designs maintained the strict environmental conditions necessary for producing machines capable of reproducing and, at times, replacing nature.

While the studio allowed Dickson to regulate light in a way that had previously eluded him, he remained not only subject to variations in weather but also to the earth’s ceaseless rotation. Nonetheless, the ability to maintain maximum light in the studio throughout much of the day changed the character of Dickson’s experimental space and took film production a step closer to independence from nature’s intractable laws. Cinema demanded natural light, and the studio captured it architecturally by ordering and reordering the sun’s rays with each studio rotation.

Far from primitive, then, the Black Maria should be understood as a cinematic version of modern technics designed to make natural light a technological form and place the sun on reserve.60 This basic principle would define the film studio. Indeed, efforts to dissociate filmmaking from the strictures of nature drove studio architecture and technology through the first decades of the twentieth century, as architects and filmmakers sought new styles of open and dynamic architectural space, new forms of reflecting and refracting glass, and, ultimately, technologies for electrical illumination. They also linked cinema to the more general efforts of architects and inventors to design materials and spaces that reproduced desirable features of the natural environment—including regulated light and heat, shelter from wind, rain, and snow, and access to clean and fresh air, food, and water—while eliminating their undesirable counterparts. Technologies produced in laboratories such as Edison’s helped make these new “well-tempered” environments possible, and films gave them another form.

Dickson further enhanced the Black Maria’s reproductive capacity by more closely following Marey’s formula for obtaining sharp and rapid exposures of movement at the Station Physiologique. Although he may have read Marey’s descriptions of the shooting procedure used at the Station before constructing the photographic building, Dickson seems to have initially ignored the details of Marey’s report. Upon closer inspection, Dickson would discover that Marey was an expert on the subject, having already designed a series of experimental recording spaces with successively more favorable results.

Indeed, Marey recognized, as Dickson would later, that the background against which he exposed his subjects had a crucial effect on the images produced. In other words, prefiguring the importance of architectural design to film form in the Black Maria, Marey’s laboratory-studios synched image production with architectural form. Having begun his experiments in 1882 against a simple wooden platform covered in black and set at a 45-degree angle to the camera, Marey soon discovered that the background reflected too much light on his glass plates. He built a new background the following year after a chemist, Eugène Chevreul, suggested photographing his subjects in front of a black box. The new “black hangar,” a 3-meter-deep shed, initially had a background painted in black that Marey and his assistant, Georges Demenÿ, later covered in even darker black velvet.61 The new hangar produced markedly sharper figures against its self-effacing black background, pushing Marey to reduce his exposure times even further in an effort to produce as many images as possible on a single glass plate.

As he described in an 1887 Scientific American Supplement article that Dickson almost certainly read, during his experiments Marey discovered that over the course of these exposures, even “small quantities of light, accumulating their effect over the whole surface of the plate, end by fogging it completely.”62 He suggested having not simply a black background but a deeply recessed area behind the figures to be recorded. For this purpose, Marey had built a third structure in 1886, now ten meters deep and equipped with curtains to change the width and height of the opening to keep reflected light to an absolute minimum.63 The new background allowed Marey to produce new experiments with birds in flight and to begin new experiments on the recording apparatus itself in an effort to find a more flexible technology that might be used for recording movement outside the laboratory.64

Dickson would use these principles and Marey’s images as part of the inspiration for both the Black Maria and its early productions. The studio’s “black tunnel” was a product of Dickson’s closer reading of Marey’s findings and, as in Marey’s research, contributed to greater success in Dickson’s motion picture production. As with the motion studies, this black tunnel also gave the Black Maria films their distinct visual form. The studio produced an aesthetic of observation and investigation that remained consistent with the studio’s continued use as an experimental laboratory and which defined early cinematic space in both the studio and its films.

THE FRAMED AESTHETIC: EARLY STUDIO SPACE AND FILM FORM

The architectural solution to the problem of photographically reproducing movement necessarily shaped its aesthetic form. The Black Maria films, produced largely between mid-1893 and early 1896 (and more sparsely into 1901), share a basic spatial form—a framed aesthetic—defined by their stark background, bright ground plane, and the central area of action that emerges between them, typically limited to a single continuous shot from a fixed camera position. Contained within the enclosed studio space, their form was equally framed within a particular visual aesthetic. The play of black, white, and gray in these films produces a kind of zero degree of film space—a simulated three-dimensionality created through the appearance of movement registered by varying intensities of reflected light. This basic setup varies, with the floor plane occasionally omitted in figural close-ups and the purity of the empty space at times interrupted by spare set pieces, especially in the latter years of the studio’s use. But the consistent repetition of spatial form in the Black Maria films offers a glimpse of the initial spatial logic—the enframing of light and objects—that defined early studio filmmaking and, to a degree, has remained in place (if hidden) ever since.

The Black Maria’s framed aesthetic emerged as a direct result of the developments in Dickson’s experimental spaces—and Marey’s before him—that yielded a method for registering sufficient light on film. Dickson solved the problem of recording movement architecturally in two main parts. First, by absorbing light in the studio’s recessed black tunnel, he created a void of unmoving space that dominates the films, typically accounting for as much as 85 percent of the frame. While at times enough light enters the studio to reveal the recessed background behind the stage, more often this space registers in the images as a kind of non-space, an empty abyss of impenetrable darkness that places the films’ moving figures in distinct relief. Before and beneath this blackened void, Dickson created its counterpart, the brightly lit stage that gleams in grays and whites beneath the studio’s open roof, interrupted only by the shadows of the figures performing above.

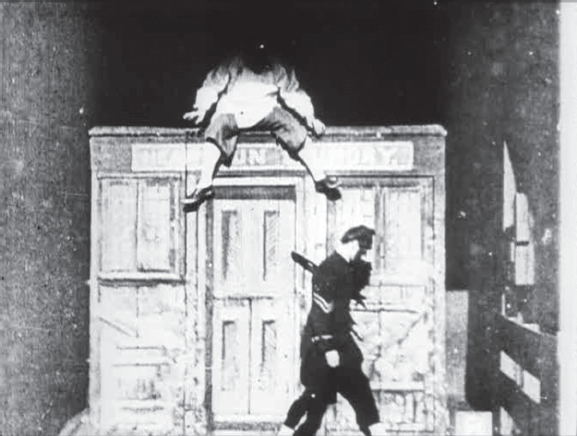

These light and dark spaces define and delimit the studio’s most basic architectural form and function. The filmed images acquire the illusion of three-dimensionality with the introduction of figures and props into the area where light and dark intersect. Suspended between the blackened recess and the illuminated base, Dickson created a plane of filmic visibility. Here, the movement of bodies and objects across the frame, reflecting light back to the Kinetograph lens, activates and deactivates portions of the image as the visible space shifts between light (figure) and dark (empty space). The results are particularly stunning in films that operate precisely on this logic of fluctuation, such as in the abstract white forms of Amy Muller (1896) (fig. 1.6) and Crissie Sheridan (1897) or the gray clouds of smoke that paint the background of Annie Oakley (1894) (fig. 1.7).

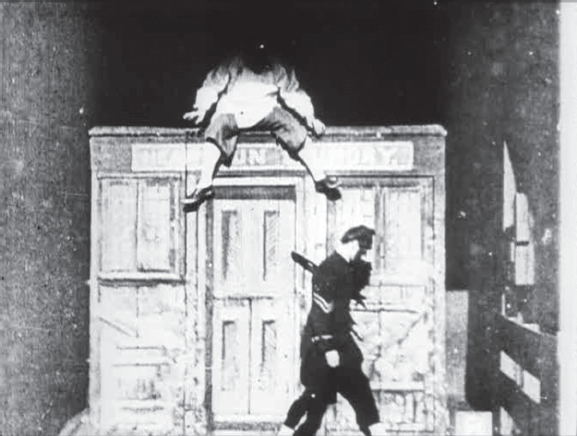

The logic of the studio frame and the bounds of its visibility were strict. In Robetta and Doretto (1894) (fig. 1.8), for instance, a rare early attempt to point the camera outside the space designated by Dickson’s architectural design leads to virtual decapitation and dismemberment as the performers exceed the studio’s visible plane. Such rare “mistakes” suggest the degree to which the studio’s form and function shaped the form of the films produced in it. This strict regulation of the space (and thus often the content) of the Black Maria films corresponded to the rigorous experimental imperatives that shaped the studio’s design.

In this respect, the framed aesthetic contributed to what Tom Gunning has termed the “cinema of attractions,” but it did so on the basis of experimental imperatives that had little concern for visual shock or spectacle and that had different long-term effects on film form.65 Like the cinema of attractions, the framed aesthetic was defined by Dickson’s intention to show something—to demonstrate the apparatus’s ability to register movement. On the other hand, it was the product of his attempts, prior to any concern with entertainment or an eventual audience’s response, to control light and generate a closed experimental world in which to do so. Thus while the framed aesthetic emerged from a system of environmental control that enhanced cinema’s ability to generate attractions, its visual form was characterized by abstract principles of clarity, legibility, and precision more than direct address, shock, or astonishment.

Indeed, if the architectural space and aesthetic form that Dickson and Heise created in these films produced entertaining scenes of performance and visual pleasure, they did so only by satisfying the experimental necessities that had inspired them. Drawing on Marey’s experimental spaces as well as his research subjects, Dickson’s framed aesthetic was, first and foremost, observational and investigational. Like Marey and Demenÿ at the Station Physiologique, Dickson made local athletes among the first subjects to “perform” in this experimental laboratory. To be sure, Dickson did not use these films or others, such as Annie Oakley, to analyze bodily movement or the behavior of projectiles. Rather, the initial film subjects allowed Dickson to investigate the performance of his experimental moving-picture apparatus. The task of investigation and observation that drove his image-making practices from the first “monkeyshines” tests in the photographic building to the earliest test films in the Black Maria left its mark on the entertainment films that followed. These tests confirmed the functionality of the studio’s architectural form and systematized the basic procedures for capturing movement that would remain consistent for commercial film production.

Given the typical subjects filmed in the studio—composed largely of vaudeville performers and variety acts—one might even argue that the investigational practice of the earlier experimental films remained both viable and desirable for entertainment-seeking audiences. The entertainers that paraded through the studio by the hundreds in the mid-1890s may not have been subjects of scientific analysis, but their acts invited close observation of their impressive corporeal feats. Especially given these films’ initial viewing context—through the eyepiece of the Kinetoscope—such acts take on the character of bodily experiments offered up for investigation to scientist-like viewers peering as if into a microscope. These practices and experiences are consistent with the “operational aesthetic” that, as Neil Harris explains, had attracted audiences since the early nineteenth century by simply putting the processes of recording and reproducing movement on display.66

Alongside its use for recording commercial films, Dickson continued, moreover, to treat the studio as an experimental laboratory until his departure from the company in 1895.67 Using Room #5, the photographic building, and the Black Maria, Dickson modified the Kinetograph while also attempting to develop commercially viable projection methods and sound systems. Perhaps the most striking instance of this continued experimentation appears in the Dickson Experimental Sound Film, produced in 1895. The film, which features Dickson in the Black Maria playing the violin while two laboratory workers dance, is the only surviving example of a series of subjects made for the experimental Kinetophonograph, a device with which Dickson attempted to combine the new motion picture apparatus with Edison’s phonograph.68

Although Edison only began manufacturing the system in 1895, the idea of linking moving images to phonograph discs dated to the earliest motion picture tests and may have even contributed to Dickson’s design for the Black Maria. The Edison laboratory had a phonograph recording studio on the third floor of the main lab building, and Dickson may have been inspired by the purity of its isolated space, either anticipating the film studio’s use for sound and image recording or in simply drawing a parallel between their mutual need for precise environmental control.69 Dickson’s attempt to create a synchronous sound system—one of his final projects for the Edison Company—not only reveals the continuing experimental imperative that conditioned the working space of the first film studio; it also anticipates the complete environmental control that filmmakers would seek as inventors and engineers adapted cinema to synchronous recorded sound over the next three decades.

In April 1895, Dickson left Edison to join a competing motion picture firm, leaving film production and development in the hands of Heise and James White. Although the two continued making films in the Black Maria, within a year it had fallen into disrepair and its use waned until Edison had the studio demolished in 1903. The end of the Black Maria was by no means, however, the end of the framed aesthetic. Dickson repeated much of this process for American Mutoscope and Biograph, the company that would emerge as Edison’s principal American competitor. In 1896 he reproduced the Black Maria’s basic functionality (in pared-down form) for Biograph’s first studio.70

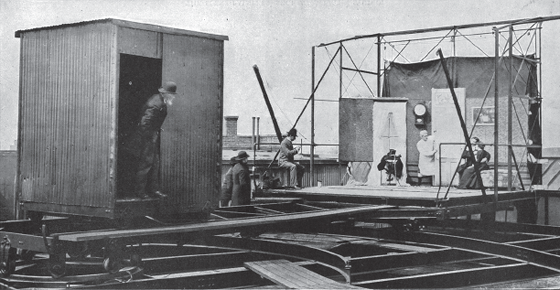

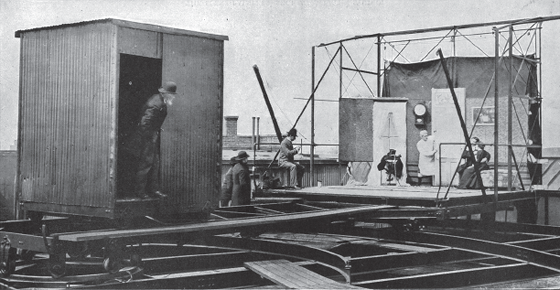

Located on the roof of the Roosevelt Building at 841 Broadway, where Biograph rented its offices, it consisted of a small shed housing the Mutograph camera and an open-air wooden stage surrounded on three sides by a system of poles for hanging backdrops and props (fig. 1.9). The two sections stood on a connected steel platform that could be rotated 180 degrees on a pivot below the camera shed, once again to follow the sun’s path. As in the Black Maria, the camera could be moved on tracks to and from the stage. Production began in mid-1896, and by the fall Dickson had already produced a small catalog of films for the company’s Mutoscope exhibitions.71

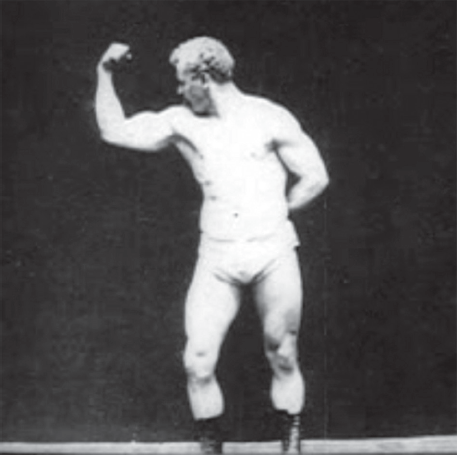

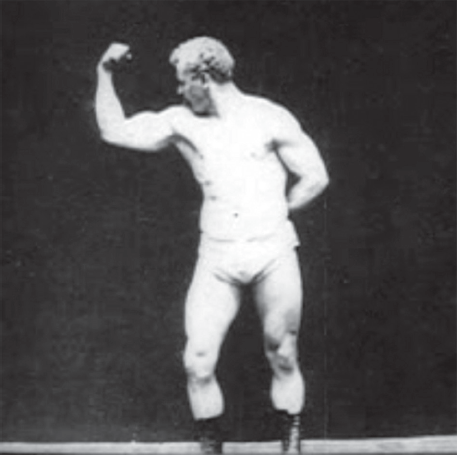

The new studio produced a similar aesthetic as its predecessor. Although Dickson did not equip it with the deep black recess that defined the Black Maria’s films, he continued to use a stark black backdrop that, thanks in part to Eastman’s increasingly sensitive film, still rendered performers in sharp relief. In films with familiar vaudeville subjects such as Sandow (1896; fig. 1.10) and Chimmie Hicks at the Races (1900), the new studio reproduced the framed aesthetic.72 Other films produced at the studio reenacted the development from the basic to increasingly complex representational backdrops seen in Edison’s films, all coexisting during the Black Maria’s use up to 1903.

Dickson reproduced this studio form two more times for Biograph, first in London near the Thames in 1898, then in Courbevoie, France, in 1899. According to Spehr, the latter studios were less elaborate than their predecessors, but Dickson never entirely abandoned the basic rotating capacity that defined his original design.73 The formal film developments engendered by these studios’ architectural forms also expanded beyond Dickson’s studios and film productions. The framed aesthetic that Dickson created in the Black Maria returned independently in the numerous workshops, laboratories, and other early film studios that produced the first moving images. Such continuity should come as little surprise given the similarity of the fundamental imperatives driving Dickson and other inventors and filmmakers. The abstract re-creation of moving objects within precisely controlled experimental environments shaped the creation of both early moving images and film aesthetics in many contexts. This process defined the genealogy of early studio space and film form, and it would continue to shape cinematic production into the early twentieth century, both inside the studio and out. In contrast to the cinema of attractions, which went “underground” around 1906 with the rise of film narratives, the framed aesthetic continued to shape film production through silent cinema and beyond.

CONCLUSION: FILM TECHNOLOGY AND THE HUMAN-BUILT WORLD, OUTSIDE THE STUDIO

Studio “enframing” remained important to cinematic picture making outside the studio walls. Much like painters and photographers before them, filmmakers left the studio with ideas about the nature of (film) space and techniques for representation that would be critical to how they framed their non-studio subjects. As art historian Svetlana Alpers has argued, as early as the seventeenth century the studio became, for some artists, “not simply the site where they worked, but the very condition of working.”74 As later painters such as Paul Cézanne shuttled between their studios and local landscapes, their experimentation with light and form in the studio necessarily shaped the way they painted outside it.75 For filmmakers such as Porter and White, the studio similarly conditioned their techniques for capturing film space, whether they were working in the studio or using its principles to guide their work on location. Born from and as spaces of technological and formal experimentation, studios offered filmmakers the space and conditions for developing their craft in ways that would shape representation beyond cinema’s first working interiors.76

As quickly as inventors created the first film technologies in their laboratories and workshops, they left those spaces to test the new devices in the world outside. The environments they captured were no doubt subject to few of the constraints placed on the artificial environments created in the first laboratories and studios, but the cinematic results were equally technological. Whether fictional films or actualities, films made out-of-doors should be understood, like their studio-produced counterparts, as the product of human-built worlds. By mechanically reproducing the natural environment—to the awe of early spectators who were captivated by early actuality films such as Birt Acres and Robert W. Paul’s Rough Sea at Dover (1895)—early filmmakers contributed to the process by which humans increasingly experienced space through technological mediation.

Conditioned by the contexts of invention and industrial development that produced early film technologies, the first filmmakers left the laboratory and studio with devices and techniques ready-made for framing and enframing the world outside through both a literal and metaphorical technological lens. Not surprisingly, the subjects they filmed often included the spaces and technologies that contributed to the transformation of the modern Western world. From common scenes of workers leaving the factory to trains, bridges, and tunnels, the modern built environment offered a perfect setting for early cinema. Films such as the Lumières’ La Sortie des usines Lumière (1895), Edison’s Union Iron Works (1898), and countless others made by companies including Pathé in France and Mitchell and Kenyon in Britain, produced recognizable scenes of industrial experience.77 Railroad films, such as Edison’s repeatedly remade Black Diamond Express (1900), and films of flying machines, steamships, and automobiles both cataloged and, especially in the so-called “phantom rides,” reproduced the conquest of space and time experienced in modern forms of travel.78 Films of civil engineering feats such as Edison’s Passaic Falls (1898) similarly emphasized the spread of technological conquest in urban and rural settings alike.

Featured categories in early film catalogs such as the “machinery” film, the “industrial,” and “railroads” attest to these subjects’ popularity. Such films both reflected and contributed to the experience of modern space as increasingly technological, urban, and artificial, an experience that was celebrated at international expositions and in the films that documented them. At the Paris 1900 Exposition, for instance, Edison Company producer James White, taking leave from the Black Maria, recorded stunning images of the architectural and technological novelties that captivated festival attendees and later film audiences, including the Palace of Electricity, the Eiffel Tower and its elevator, and the Exposition’s moving boardwalks. These spaces and technologies offered filmmakers a seemingly ideal testing ground for the new film technologies produced in their laboratories and studios. In Paris, for instance, White used a new rotating tripod head to create panoramic films that offered viewers a technological experience of space that, although consistent with earlier experiences in panoramas and dioramas, constituted a new form of modern spatial experience. As Anne Friedberg has argued, these films reproduced the effect of the Exposition’s transport technologies and created their cinematic equivalent through virtual mobility across space and time.79

The following year at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, White and new Edison employee and future studio head Edwin S. Porter used the rotating tripod technology to produce similar cinematic effects in the “City of Living Light.” Like the Exposition’s extravagant electrical light display, these films referred, in Kristen Whissel’s words, “to the subordination of nature by modern technology.”80 Each evening the Exposition lights were slowly brought to full brightness just before dark, only to be slowly turned off to reproduce the sunset. As one commentator described, “it is a new kind of brilliancy. You are face to face with the most magnificent and artistic nocturnal scene that man has ever made.”81 In mid-October, Porter and White produced this event’s cinematic analog, a panoramic testament to cinema’s power to reproduce and control the effects of the sun. They created the film, Pan-American Exposition by Night, by commencing the panorama during daylight hours, rotating the camera approximately ninety degrees to face the Exposition’s Tower of Electricity before turning the camera off to wait for the sunset; after dark, they turned the camera back on, continuing the pan at the same constant speed, thereby creating the effect of a sudden transformation from day to night.

The Edison Company catalog described the film as “pronounced by the photographic profession to be a marvel in photography, and by theatrical people to be the greatest winner in panoramic views ever placed before the public.” As Whissel argues, it “simultaneously enacted and aestheticized technological modernity’s transcendence of the natural order through electricity’s disassociation of light from time.”82 This disassociation—produced at the very moment when White and Porter abandoned the Black Maria in favor of Edison’s new studio in Manhattan—recalled the studio’s own radical attempt to defy nature through film technology. The Exposition’s reproduction of the effects of nature through the precise ordering of its technological environment paralleled the techniques used in contemporary film studios to replicate the effects of nature needed for film production. In their films of the Exposition, Porter and White took advantage of these conditions to build cinematic worlds that were continuous with the technologies on display both in the City of Living Light and, increasingly, in cities across the Western world.

The practice of choosing and changing the spaces of non-studio film production was repeated in less extravagant form in the growing practice of outdoor shooting that emerged at the turn of the century (and later on studio backlots). In extending their studio techniques to location filming, to what degree did these filmmakers also extend the studio’s technological enframing of nature? As I suggested at the beginning of this chapter, Martin Heidegger’s visual metaphor for technological enframing offers one way of understanding the relationship between film technology and nature outside the studio. As Samuel Weber describes, for Heidegger technology produced “the world brought forth and set before the subject, whose place thus seems secured by the object of its representation.”83 Cinema did so literally: filmmakers secured views of the world and sent them back to fascinated audiences who came to know it increasingly through its photographic reproductions. As Mumford similarly described, as a “specific art of the machine,” cinema provided an important way of experiencing the world that was consistent with the broader experiences of technological change. For Mumford, film gave its viewers a contradictory form of access to the fleeting experience of nature. Precisely by capturing it mechanically, cinema made nature newly accessible—as a technological “world picture”—to audiences conditioned by the technological experience of the modern world.84

This view of the relationship between cinematic technology and nature reflects the contradictions involved in early filmmakers’ constructions of film space, first in the studio, but also in the changing built environment. With the Black Maria, Dickson created a remarkable machine for producing images through precise environmental control that was nonetheless constrained by the natural processes it sought to escape. The tension between technology and nature in film production would continue to condition the design of film studios into the new century, perhaps no more clearly than in the “glass house” studio designs inaugurated by Georges Méliès in France in 1897 and Robert W. Paul in Britain the following year. While these studios did not derive from the precision spaces and practices of laboratories such as Edison’s, they shared a need for rigorous environmental control. Their designers created it by drawing on a different set of influences that contributed to new ways of generating, controlling, and manipulating film space. Even if the dictates of scientific observation and investigation were shed during the development of the studio as a space of film production, the strict regulation of space continued to shape the practices and forms of film, as well as the nature of film space—a highly regulated, ordered, artificial reproduction of the natural environment.